Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Extending The Horn Range

Uploaded by

api-266770330Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Extending The Horn Range

Uploaded by

api-266770330Copyright:

Available Formats

Extending Horn Range

H

arvey Phillips once stated that

his instrument had three reg-

isters, "the upper register, the

lower register, and the cash register,"

and while hornists may be more com-

fortable playing in either the high or

low register, the days of specialization

are gone. In orchestral playing high

horns use the lower range in Strauss'

Till Eulenspiegel, Shostakovich's Sym-

phony No. 5, and Mussorgsky's Pic-

tures at an Exhibition, and low horns

play in the upper register on Mozart's

Symphony No. 29 in A Major,

Mahler's Symphony No. 1, and

Strauss' Ein Heldenleben. Such con-

temporary solo works as Sigmund

Berg's Horn Lok, Vitaly Bujanovski's

Country Sketches, Thomas Beversdorfs

by Eldon Matlick

Sonata for Horn and Piano, and

Joseph Rheinberger's Sonata for Horn

and Piano use a broad range. In an

age of increasing competition for

fewer positions, students should work

for control in all registers and follow

Philip Parkas' advice to "develop the

entire command of your instrument.

You cannot afford to wait for horn

vacancies for your selected specialty."

While there is no miracle cure for

high or low range problems, most

arise from inadequate air support and

poor embouchure control. Hornists

can feel the changes in air support

and embouchure in different octaves

by singing a middle register note and

moving stepwise either up or down,

noting differences in vowel sound, jaw

position, tongue placement, and air

use. Usually singing causes a higher

tongue and jaw position on high notes

while abdominal muscles change posi-

tion for a faster air velocity.

Whistling a familiar tune demon-

strates the proper use of air and em-

bouchure; there is a correlation be-

tween the highest whistled note and

the upper horn note in a player's

range. This is a good exercise even for

players who cannot produce a sound

while whistling. Keep one hand in

front of the mouth while whistling to

feel the air stream with the other

hand placed on the lower abdomen to;

feel how these muscles work. Avoid

clamped lips, as when saying an ra

syllable, and instead use an oo sha]

for every note,

aperture will fi

camera shutter

as abdominal t

is what shoulc

higher notes on

Once this c

with whistling

mouthpiece bu:

additional praci

per range if stm

rectly. First pla

and strive for a

ty. Place one 1

mouthpiece sha.

of air producir*

perfect fourth a:

quality; each p:

same quantity c

loss of air veloc

piece shank. Ne:

the same intervE

ty of the buzzinj

wind. After perl

to sixths or octa

The next exer

thodox, but it i

holding the inst

index finger in

stead of the pin

thumb alongside

the mouthpiece

smallest pressure

!5; without mot

quality wil l "

should be played

Jy the vibratin

the mouthp:

} pitch in this e>

1 C, gently focu

! next harmonic

ar between n

ving sequenc-

i only with a :

notes.

poiliblt

for every note. As the pitch rises the

aperture will focus each note like a

camera shutter with air moving faster

as abdominal muscles contract. This

is what should occur when playing

higher notes on the horn.

Once this concept is established

with whistling exercises, move on to

mouthpiece buzzing. No amount of

additional practice will develop an up-

per range if students do not buzz cor-

rectly. First play a comfortable pitch

and strive for a vibrant, breathy quali-

ty. Place one hand in front of the

mouthpiece shank to feel the amount

of air producing this sound. Buzz a

perfect fourth and listen to the sound

quality; each pitch should have the

same quantity of wind noise and no

loss of air velocity from the mouth-

piece shank. Next play a glissando over

the same interval, checking the quali-

ty of the buzzing and the quantity of

wind. After perfect fourths, move on

to sixths or octaves.

The next exercise may seem unor-

thodox, but it is effective. Begin by

holding the instrument with the left

index finger in the finger hook, in-

stead of the pinky, and placing the

thumb alongside the leadpipe. Rest

the mouthpiece on the lips with the

smallest pressure possible and play

C5; without mouthpiece pressure the

buzz quality will be airy. This exercise

should be played on the open F horn.

I Only the vibrating edge of the lip in-

Iside the mouthpiece should control

i the pitch in this exercise. After the ini-

1 tial C, gently focus the lip to produce

I the next harmonic, D, with a glissando

Ismear between notes. In playing the

I following sequence, move to the next

I pitch only with a smooth glissando be-

irween notes.

Charles Kavalovski of the Boston

Symphony Orchestra uses an over-

tone exercise covering the entire horn

range. Begin with the second over-

tone, C3, on open F horn and slowly

play all notes in the natural harmonic

series up to the 16th partial, C6. Use a

breathy buzz throughout, never forc-

ing or pinching any upper notes; for

difficult pitches stop ascending and

work up to them. Move in a measured

fashion, slurring between partials

played as quarter, eighth, and six-

teenth notes. Advanced players

should work towards playing all of

these partials in a three octave gliss to

prepare for clean, wide range slurs.

gliss

Players with a stiff, dull tone are

usually over-using the interior em-

bouchure muscles, making them too

rigid to vibrate. Fred Fox devoted a

chapter of his book The Essentials of

Brass Playing to this problem and in-

cluded a four-note diatonic slur exer-

cise in which the aperture only fo-

cuses the initial middle-range note,

while other notes are played changing

only air velocity, which makes them

under-focused and flat.

mp

f

To further develop aperture, upper

register, and control of lip trills the

following Bb horn exercises work par-

ticularly well. Perform all of these ex-

ercises on second and third valve

combinations ascending chromatic'

ally to open notes. Produce the

pitches with the vibrating edge of the

lip at a mezzo-piano volume, playing

upper notes with a small bump of air

from the lower abdominal muscles;

the lips should not focus down on the

upper notes for any reason.

^

=^

=t=

Blow directly into the center of the

mouthpiece cone when performing as-

cending passages. Too often inexperi-

enced students perform extended

scales or arpeggios by directing the air

stream down toward the side of the

mouthpiece wall. This helps playing

problematic upper notes, but the tone

quality suffers. Play a one octave ar-

peggio starting on second line G and

make a conscious effort to bend the

air stream steadily downwards. Re-

peat this paying close attention to the

quality and freedom of tone. Then

perform the same arpeggio striving to

keep the air stream moving straight

ahead on every pitch. If this pro-

cedure does not immediately improve

the tone and consistency, imagine

whistling the arpeggio. Transfer this

action to playing and notice the ease

and fullness of tone.

To develop a strong air stream ima-

gine blowing the upper notes out-

wards past the music stand. For exam-

ple, think of C4 as being one foot

away, C5 three feet away, and C6

blown by an air stream that reaches

eight feet. Approaching high notes ac-

cording to their vertical position on

the staff often causes players to

squeeze and pinch, but by thinking of

blowing out horizontally with a con-

trolled air direction, the pitches will

sound more easily.

Students should use the same wind

and aperture control for a solid low

range. On descending notes the aper-

ture enlarges and should vibrate freely

with firm corners and the chin

pointed down; if the embouchure is

firmly set, the aperture will enlarge in

the correct elliptical shape. An en-

Eldon Matlick is assistant professor of

horn at the University of Oklahoma

School of Music, principal ham with the

Oklahoma City Philharmonic Orchestra,

a former finalist in the Heldenleben In-

ternational Horn Competition, and a fre-

quent recitalist and clinician. He holds an

M.M. in performance from Indiana Uni-

versity, and a B.M.E. from Eastern Ken-

tucky University, and is presently a doc-

toral candidate in brass pedagogy at Indi-

ana University,

SEPTEMBER 1992 / THE INSTRUMENTALIST 47

You might also like

- Teaching Brass Instruments: How Are They Alike? Sound ProductionDocument14 pagesTeaching Brass Instruments: How Are They Alike? Sound ProductionHugo PONo ratings yet

- Euph Ped 2Document5 pagesEuph Ped 2api-266767873No ratings yet

- "Buddah Lee" - Flexibility and Clef ReadingDocument4 pages"Buddah Lee" - Flexibility and Clef ReadingAlvaro Suarez VazquezNo ratings yet

- Horn MultiphonicsDocument2 pagesHorn MultiphonicsGabriel AraújoNo ratings yet

- Tuba Pedagogy 3Document3 pagesTuba Pedagogy 3api-375765079No ratings yet

- Trombone Perf 3Document3 pagesTrombone Perf 3api-375765079No ratings yet

- Horns Mouthpieces and MutesDocument4 pagesHorns Mouthpieces and Mutesapi-425284294No ratings yet

- Horn Syl Lab Us Complete 13Document17 pagesHorn Syl Lab Us Complete 13Jennifer LaiNo ratings yet

- Ten PiecesDocument12 pagesTen PiecesSergio Bono Felix100% (1)

- Alto Trombone CD - Works by Ewazen, BolterDocument2 pagesAlto Trombone CD - Works by Ewazen, Bolterokksekk50% (2)

- Mii Channel Music For Brass Quintet-Score and PartsDocument8 pagesMii Channel Music For Brass Quintet-Score and PartsDouglas HolcombNo ratings yet

- Brass & Percussion: 2021 All-State Concert Band Audition RequirementsDocument17 pagesBrass & Percussion: 2021 All-State Concert Band Audition RequirementsSamuel AlexandriaNo ratings yet

- Tuning Double HornDocument1 pageTuning Double Hornapi-429126109No ratings yet

- AppliedTbnSyllabus2006 07Document21 pagesAppliedTbnSyllabus2006 07Emil-George Atanassov100% (1)

- First Lessons On: by Harvey Phillips and Roger RoccoDocument4 pagesFirst Lessons On: by Harvey Phillips and Roger Roccoapi-429126109No ratings yet

- Boosey &. Co.'S Successes!: Besson & Co., LTD., LondonDocument12 pagesBoosey &. Co.'S Successes!: Besson & Co., LTD., LondonDe Marco DiegoNo ratings yet

- Tuning The BandDocument2 pagesTuning The BandJeremy Williamson100% (1)

- Tuba Pedagogy2Document9 pagesTuba Pedagogy2api-477941527No ratings yet

- Essential Table of Transpositions RevDocument2 pagesEssential Table of Transpositions RevPrince SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Euphonium Pedagogy 4Document15 pagesEuphonium Pedagogy 4api-375765079No ratings yet

- PVAMU Marching Storm Band Handbook HistoryDocument20 pagesPVAMU Marching Storm Band Handbook HistoryEric JimenezNo ratings yet

- Bass Trombone Syl Lab Us Complete 13Document12 pagesBass Trombone Syl Lab Us Complete 13Behrang KhaliliNo ratings yet

- The Euphonium in Chamber MusicDocument2 pagesThe Euphonium in Chamber Musicapi-266770330100% (2)

- Entrance Exam Programme Brass InstrumentsDocument7 pagesEntrance Exam Programme Brass InstrumentsAndres RGNo ratings yet

- Langey 12 Grand StudiesDocument19 pagesLangey 12 Grand StudiesCathrine PoxanneNo ratings yet

- Trombone 5Document2 pagesTrombone 5api-478072129No ratings yet

- Trombone PresentationDocument13 pagesTrombone Presentationapi-279598006No ratings yet

- Lip Slurs: For Trombone/EuphoniumDocument1 pageLip Slurs: For Trombone/EuphoniumElkine Pierre100% (1)

- Audition Information: Level 1 Title Composer (S) Publisher (S)Document2 pagesAudition Information: Level 1 Title Composer (S) Publisher (S)Jon HebberthNo ratings yet

- Rutinas AlessiDocument46 pagesRutinas Alessiischel100% (1)

- Fine Sonata Bass Clef Euphonium PartDocument6 pagesFine Sonata Bass Clef Euphonium Partscook6891No ratings yet

- hyden 2 trumpetsDocument7 pageshyden 2 trumpetsFacundo Ezequiel ZalazarNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument19 pagesNew Text DocumentEmad VashahiNo ratings yet

- Euphonium MouthpiecesDocument4 pagesEuphonium Mouthpiecesapi-266770330100% (1)

- Troyka - From Pass-Offs To PassionDocument5 pagesTroyka - From Pass-Offs To PassionJeremy WilliamsonNo ratings yet

- March Performance TipsDocument7 pagesMarch Performance TipsAlex MoralesNo ratings yet

- Horn Call - October 2016 Natural Horn Technique Guiding Modern Orchestral PerformanceDocument2 pagesHorn Call - October 2016 Natural Horn Technique Guiding Modern Orchestral Performanceapi-571012069No ratings yet

- Wind Band Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesWind Band Literature Reviewapi-437827731No ratings yet

- Complete Warm-Up Routine for Brass PlayersDocument6 pagesComplete Warm-Up Routine for Brass PlayersLuigi Lillo Cipollone50% (2)

- Ludema, Eddie (DM Trumpet) PDFDocument99 pagesLudema, Eddie (DM Trumpet) PDFThomasNo ratings yet

- Derek Bourgeois Solo Trombone PDFDocument12 pagesDerek Bourgeois Solo Trombone PDFNonny Chakrit NoosawatNo ratings yet

- Basic Tuba Fingerings ChartDocument1 pageBasic Tuba Fingerings ChartgeheimeranonyNo ratings yet

- 22experts Excerpts For Euphonium 22 Euph Rep 1Document3 pages22experts Excerpts For Euphonium 22 Euph Rep 1api-425394984No ratings yet

- 2003 Troyka1 PDFDocument11 pages2003 Troyka1 PDFedensaxNo ratings yet

- Quick Reference Performance Guide For Marches: by Jim DaughtersDocument6 pagesQuick Reference Performance Guide For Marches: by Jim Daughtersอัศวิน นาดีNo ratings yet

- District 8 High School Concert MPA: J/S-C BBDocument3 pagesDistrict 8 High School Concert MPA: J/S-C BBMatt MalhiotNo ratings yet

- STARDUST-Partitura y PartesDocument30 pagesSTARDUST-Partitura y PartesPewa CisnerosNo ratings yet

- The Physics of Trombones and Other Brass InstrumentsDocument7 pagesThe Physics of Trombones and Other Brass Instrumentsapi-246728123No ratings yet

- Championship Sports Pak - 00. Full ScoreDocument4 pagesChampionship Sports Pak - 00. Full ScoreFabiano Aparecido de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- All State Audition Requirements Rotation C 1Document9 pagesAll State Audition Requirements Rotation C 1Cather LyonsNo ratings yet

- Peer Gynt: Edvard Grieg, Composer M.L. Lake, ArrangerDocument20 pagesPeer Gynt: Edvard Grieg, Composer M.L. Lake, ArrangerMarco ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Tuning Your Tuba NewDocument2 pagesTuning Your Tuba Newapi-425284294No ratings yet

- Wagner-Walkure Extract For 5Document18 pagesWagner-Walkure Extract For 5NachoNo ratings yet

- Tuba Excerpts F19Document5 pagesTuba Excerpts F19Kenny TsaoNo ratings yet

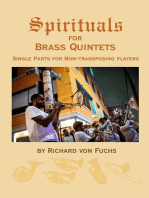

- Spirituals for Brass Quintets: Single Parts for Non-Transposing PlayersFrom EverandSpirituals for Brass Quintets: Single Parts for Non-Transposing PlayersNo ratings yet

- Traditional Tunes - Easy Trumpet duetsFrom EverandTraditional Tunes - Easy Trumpet duetsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Introducing Bass TromboneDocument5 pagesIntroducing Bass Tromboneapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Performance PracticeDocument4 pagesPerformance Practiceapi-331053430No ratings yet

- Euph Equip 1Document2 pagesEuph Equip 1api-266767873No ratings yet

- Euphonium ScoringDocument2 pagesEuphonium Scoringapi-266770330100% (1)

- On Trombones Mastering LegatoDocument6 pagesOn Trombones Mastering Legatoapi-266770330100% (1)

- Weighty ProblemsDocument2 pagesWeighty Problemsapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Teaching Beginning Trombone PlayersDocument4 pagesTeaching Beginning Trombone Playersapi-266770330100% (2)

- Difficult Trombone PassagesDocument5 pagesDifficult Trombone Passagesapi-340836737No ratings yet

- Trombone Warm UpsDocument6 pagesTrombone Warm Upsapi-331053430100% (1)

- Euphonium MouthpiecesDocument4 pagesEuphonium Mouthpiecesapi-266770330100% (1)

- Euph Perf 1Document4 pagesEuph Perf 1api-266767873No ratings yet

- The Euphonium in Chamber MusicDocument2 pagesThe Euphonium in Chamber Musicapi-266770330100% (2)

- Euphonium TechniqueDocument4 pagesEuphonium Techniqueapi-266770330100% (1)

- Euph TalkDocument4 pagesEuph Talkapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Trombone Buying GuideDocument2 pagesTrombone Buying Guideapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Trombone BasicsDocument3 pagesTrombone Basicsapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Tuba in The TubDocument2 pagesTuba in The Tubapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Tuba BasicsDocument3 pagesTuba Basicsapi-267335331No ratings yet

- Tuba Solos and StudiesDocument1 pageTuba Solos and Studiesapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Tubas StandsDocument2 pagesTubas Standsapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Developing A Melodic TubaDocument4 pagesDeveloping A Melodic Tubaapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Review of Tuba RepDocument3 pagesReview of Tuba Repapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Bach ManualDocument35 pagesBach Manualapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Tuba Perf 1Document3 pagesTuba Perf 1api-266767873No ratings yet

- Beginning TubaDocument4 pagesBeginning Tubaapi-266770330No ratings yet

- The MouthpieceDocument5 pagesThe Mouthpieceapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Opportunities For The TubistDocument2 pagesOpportunities For The Tubistapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Transposition ChartDocument1 pageTransposition Chartapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Horn Basics 2aDocument3 pagesHorn Basics 2aapi-266767873No ratings yet

- Horn Change ChartDocument1 pageHorn Change Chartapi-266770330No ratings yet

- Johannes BrahmsDocument20 pagesJohannes BrahmsEduardo PortugalNo ratings yet

- Jazz ModesDocument12 pagesJazz Modeschloe and iris in wonderland unicornNo ratings yet

- Smither, 1964Document36 pagesSmither, 1964Meriç Esen100% (1)

- Keith Jarrett Part 2d Transcription from Tokyo Solo 2002Document6 pagesKeith Jarrett Part 2d Transcription from Tokyo Solo 2002Carlo Steno Rossi100% (4)

- Periods of European Art MusicDocument6 pagesPeriods of European Art MusicandresgunNo ratings yet

- Cissy Strut - Drum Magazine - Nov 2010 PDFDocument3 pagesCissy Strut - Drum Magazine - Nov 2010 PDFbakobolt59100% (1)

- Mozart Divertimento PDFDocument2 pagesMozart Divertimento PDF陳品珍No ratings yet

- 15 76 1 PB PDFDocument8 pages15 76 1 PB PDFFlavio SilvaNo ratings yet

- Katamari Damacy - Fugue 7777Document1 pageKatamari Damacy - Fugue 7777Edward WellmanNo ratings yet

- Cygnus Garden - MapleStory Symphony in Budapest Piano Ver. - by PomaDocument4 pagesCygnus Garden - MapleStory Symphony in Budapest Piano Ver. - by PomaRima K.100% (1)

- Prelude For Organ: How Long, O Lord by Brent HughDocument7 pagesPrelude For Organ: How Long, O Lord by Brent HughBrent HughNo ratings yet

- Passing ChordsDocument7 pagesPassing ChordsStalin CastroNo ratings yet

- ONCE and Again, Evolution of A Legendary FestivalDocument57 pagesONCE and Again, Evolution of A Legendary FestivalManuel Alfredo Ayulo RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 10 Jazz BluesDocument4 pages10 Jazz BluesAnonymous 26kU5IvyKS100% (4)

- RCM Level 5 SyllabusDocument7 pagesRCM Level 5 SyllabusCourtney DizonNo ratings yet

- History of Classical Music PDFDocument55 pagesHistory of Classical Music PDFJohannJoeAguirreNo ratings yet

- Voicing and Revoicing Quartal Chords PDFDocument4 pagesVoicing and Revoicing Quartal Chords PDFRosa victoria paredes wong100% (1)

- Azu Etd 11721 Sip1 MDocument84 pagesAzu Etd 11721 Sip1 MSanti CuencaNo ratings yet

- 24 Gypsy Jazz Standards BB Edition PDFDocument29 pages24 Gypsy Jazz Standards BB Edition PDFpmasax100% (2)

- Learn Piano Chords For Free - Major, Minor, 7th ChordsDocument4 pagesLearn Piano Chords For Free - Major, Minor, 7th ChordsraduseicaNo ratings yet

- All Hail ScoreDocument1 pageAll Hail Scorerobz35No ratings yet

- Kaval Sviri Simile-Violin 2Document1 pageKaval Sviri Simile-Violin 2Mark ScottNo ratings yet

- John Lowen Magat - Music of Lowlands of Luzon Folk Songs From The LowlandsDocument26 pagesJohn Lowen Magat - Music of Lowlands of Luzon Folk Songs From The LowlandsJohn lowen magatNo ratings yet

- EvTon2BkInside1703aA5 PDFDocument600 pagesEvTon2BkInside1703aA5 PDFAlejandro BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Jean AbsilDocument4 pagesJean AbsilSergio Miguel MiguelNo ratings yet

- Lei Liang - Harp ConcertoDocument79 pagesLei Liang - Harp ConcertoJ.W Zach (BB)No ratings yet

- Beethoven Sonata32 Op111Document21 pagesBeethoven Sonata32 Op111Anita-Rose VellaNo ratings yet

- Berklee Online Songwriting Degree HandbookDocument89 pagesBerklee Online Songwriting Degree Handbookzandi lorenzoNo ratings yet