Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PALS Political Law Doctrinal Syllabus

Uploaded by

Ona DlanorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PALS Political Law Doctrinal Syllabus

Uploaded by

Ona DlanorCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurisprudence Political Law

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

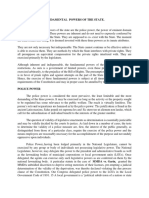

INHERENT POWERS OF THE STATE

POLICE POWER

In the exercise of police power, the State can regulate the rates imposed by a public utility such as

SURNECO. Hence, the ERC simply performed its mandate to protect the public interest imbued in

those rates. SURIGAO DEL NORTE ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE, INC. (SURNECO) v. ENERGY

REGULATORY COMMISSION, G.R. No. 183626, October 04, 2010

A mayor cannot be compelled by mandamus to issue a business permit since the exercise of the

same is a delegated police power hence, discretionary in nature. ABRAHAM RIMANDO v.

NAGUILAN EMISSION TESTING CENTER, INC., et al., G.R. No. 198860, July 23, 2012

Traditional distinctions exist between police power and eminent domain. In the exercise of police

power, a property right is impaired by regulation, or the use of property is merely prohibited,

regulated or restricted to promote public welfare. In such cases, there is no compensable taking,

hence, payment of just compensation is not required. On the other hand, in the exercise of the

power of eminent domain, property interests are appropriated and applied to some public purpose

which necessitates the payment of just compensation therefor. MANILA MEMORIAL PARK, INC.

AND LA FUNERARIA PAZ-SUCAT, INC. v. SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL

WELFARE AND DEVELOPMENT and THE SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE, G.R.

No. 175356, December 3, 2013

STATE IMMUNITY FROM SUIT

An immunity statute does not, and cannot, rule out a review by this Court of the Ombudsmans

exercise of discretion, however, the Courts intervention only occurs when a clear and grave abuse

of the exercise of discretion is shown. ERDITO QUARTO v. THE HONORABLE OMBUDSMAN

SIMEON MARCELO, et al., G.R. No. 169042, October 5, 2011

The state may not be sued without its consent. Likewise, public officials may not be sued for acts

done in the performance of their official functions or within the scope of their authority.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, et al. v. PHIL PHARMAWEALTH, INC., G.R. No. 182358, February

20, 2013

The general rule is that a state may not be sued, but it may be the subject of a suit if it consents to be

sued, either expressly or impliedly. There is express consent when a law so provides, while there is

implied consent when the State enters into a contract or it itself commences litigation. This Court

explained that in order to determine implied waiver when the State or its agency entered into a

contract, there is a need to distinguish whether the contract was entered into in its governmental or

proprietary capacity. HEIRS OF DIOSDADO MENDOZA ET AL. v. DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC

WORKS AND HIGHWAYS, G.R. No. 203834, July 9, 2014

The DPWH is an unincorporated government agency without any separate juridical personality of

its own and it enjoys immunity from suit. HEIRS OF DIOSDADO MENDOZA ET AL. v.

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS, G.R. No. 203834, July 9, 2014

Page 1 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

SEPARATION OF POWERS

The President, Congress and the Court cannot create indirectly franchises that are exclusive in

character by allowing the Board of Directors (BOD) of a water district and the Local Water Utilities

Administration (LWUA) to create franchises that are exclusive in character. TAWANG MULTIPURPOSE COOPERATIVE v. LA TRINIDAD WATER DISTRICT, G.R. No. 166471, March 22, 2011

Consistent with the principle of separation of powers enshrined in the Constitution, the Court

deems it a sound judicial policy not to interfere in the conduct of preliminary investigations, and to

allow the Executive Department, through the Department of Justice, exclusively to determine what

constitutes sufficient evidence to establish probable cause for the prosecution of supposed

offenders. By way of exception, however, judicial review may be allowed where it is clearly

established that the public prosecutor committed grave abuse of discretion, that is, when he has

exercised his discretion in an arbitrary, capricious, whimsical or despotic manner by reason of

passion or personal hostility, patent and gross enough as to amount to an evasion of a positive duty

or virtual refusal to perform a duty enjoined by law. Hence, in matters involving the exercise of

judgment and discretion, mandamus may only be resorted to in order to compel respondent

tribunal, corporation, board, officer or person to take action, but it cannot be used to direct the

manner or the particular way discretion is to be exercised, or to compel the retraction or reversal of

an action already taken in the exercise of judgment or discretion. DATU ANDAL AMPATUAN JR. v.

SEC. LEILA DE LIMA, as Secretary of the Department of Justice, CSP CLARO ARELLANO, as

Chief State Prosecutor, National Prosecution Service, and PANEL OF PROSECUTORS OF THE

MAGUINDANAO MASSACRE, headed by RSP PETER MEDALLE, G.R. No. 197291, April 3, 2013

Where the Executive Department implements a relocation of government center, the same is valid

unless the implementation is contrary to law, morals, public law and public policy and the Court

cannot intervene in the legitimate exercise of power of the executive. The rationale is hinged on the

principle of separation of powers which ordains that each of the three great government branches

has exclusive cognizance of and is supreme in concerns falling within its own constitutionally

allocated sphere. REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, represented by ABUSAMA M. ALID, Officerin-Charge, DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE - REGIONAL FIELD UNIT XII (DA-RFU XII) v.

ABDULWAHAB A. BAYAO, OSMEA I. MONTAER, RAKMA B. BUISAN, HELEN M. ALVAREZ,

NEILA P. LIMBA, ELIZABETH B. PUSTA, ANNA MAE A. SIDENO, UDTOG B. TABONG, JOHN S.

KAMENZA, DELIA R. SUBALDO, DAYANG W. MACMOD, FLORENCE S. TAYUAN, in their own

behalf and in behalf of the other officials and employees of DA-RFU XII, G.R. No. 179492, June

5, 2013

CHECKS AND BALANCES

Any form of interference by the Legislative or the Executive on the Judiciarys fiscal autonomy

amounts to an improper check on a co-equal branch of government. RE: COA OPINION ON THE

COMPUTATION OF THE APPRAISED VALUE OF THE PROPERTIES PURCHASED BY THE

RETIRED CHIEF/ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT, A.M. No. 11-7-10-SC, July 31,

2012

VOID FOR VAGUENESS DOCTRINE

Page 2 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

The doctrines of strict scrutiny, overbreadth, and vagueness are analytical tools developed for

testing "on their faces" statutes in free speech cases. They cannot be made to do service when what

is involved is a criminal statute. SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE ENGAGEMENT NETWORK, INC., v.

ANTI-TERRORISM COUNCIL, et.al., G.R. No. 178552, October 05, 2010

CONSTITUTIONALITY

Republic Act No. (R.A.) 9335, otherwise known as the Attrition Act of 2005 and its IRR are

constitutional. BUREAU OF (CUSTOMS EMPLOYEES ASSOCIATION (BOCEA) v. HON.

MARGARITO B. TEVES, G.R. No. 181704, December 6, 2011

The Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995 is valid and constitutional. HON.

PATRICIA A. STO. TOMAS, et al. v. REY SALAC, et al., G.R. No. 152642, November 13, 2012

A statute having a single general subject, indicated in the title, may contain any number of

provisions, no matter how diverse they may be, so long as they are not inconsistent with or foreign

to the general subject, and may be considered in furtherance of such subject by providing for the

method and means of carrying out the general subject. HENRY R. GIRON v. COMELEC, G.R. No.

188179, January 22, 2013

The government has a right to ensure that only qualified persons, in possession of sufficient

academic knowledge and teaching skills, are allowed to teach in such institutions, thus, the

requirement of a masteral degree for tertiary education teachers is not unreasonable. UNIVERSITY

OF THE EAST v. ANALIZA F. PEPANIO AND MARITI D. BUENO, G.R. No. 193897, January 23,

2013

The tests to determine if an ordinance is valid and constitutional are divided into the formal (i.e.,

whether the ordinance was enacted within the corporate powers of the LGU, and whether it was

passed in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law), and the substantive (i.e., involving

inherent merit, like the conformity of the ordinance with the limitations under the Constitution and

the statutes, as well as with the requirements of fairness and reason, and its consistency with public

policy).

As to substantive due process, Ordinance No. 1664 met the substantive tests of validity and

constitutionality by its conformity with the limitations under the Constitution and the statutes, as

well as with the requirements of fairness and reason, and its consistency with public policy.

Considering that traffic congestions were already retarding the growth and progress in the

population and economic centers of the country, the plain objective of Ordinance No. 1664 was to

serve the public interest and advance the general welfare in the City of Cebu. Its adoption was,

therefore, in order to fulfill the compelling government purpose. With regard to procedural process

the clamping of the petitioners vehicles was within the exceptions dispensing with notice and

hearing. As already said, the immobilization of illegally parked vehicles by clamping the tires was

necessary because the transgressors were not around at the time of apprehension. Under such

circumstance, notice and hearing would be superfluous. VALENTINO L. LEGASPI v. CITY OF CEBU,

et al./BIENVENIDO P. JABAN, SR., et al. v. COURT OF APPEALS, et al., G.R. No. 159110/G.R. No.

159692. December 10, 2013

Page 3 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

There is no deprivation of property as no restriction on their use and enjoyment of property is

caused by the implementation of R.A. 9646. If petitioners as property owners feel burdened by the

new requirement of engaging the services of only licensed real estate professionals in the sale and

marketing of their properties, such is an unavoidable consequence of a reasonable regulatory

measure. No right is absolute, and the proper regulation of a profession, calling, business or trade

has always been upheld as a legitimate subject of a valid exercise of the police power of the State.

The legislature recognized the importance of professionalizing the ranks of real estate practitioners

by increasing their competence and raising ethical standards as real property transactions are

susceptible to manipulation and corruption. REMMAN ENTERPRISES, INC. v. PROFESSIONAL

REGULATORY BOARD OF REAL ESTATE SERVICE, G.R. No. 197676; February 4, 2014

The petitioner who claims the unconstitutionality of a law has the burden of showing first that the

case cannot be resolved unless the disposition of the constitutional question that he raised is

unavoidable. If there is some other ground upon which the court may rest its judgment, that course

will be adopted and the question of constitutionality should be avoided. Thus, to justify the

nullification of a law, there must be a clear and unequivocal breach of the Constitution, and not one

that is doubtful, speculative or argumentative. KALIPUNAN NG DAMAYANG MAHIHIRAP,

INC., v. JESSIE ROBREDO, G.R. No. 200903, July 22, 2014

LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT

The clear intent, express wording, and party-list structure ordained in Section 5 (1) and (2), Article

VI of the 1987 Constitution cannot be disputed: the party-list system is not for sectoral parties only,

but also for non-sectoral parties. Thus, the party-list system is composed of three different groups:

(1) national parties or organizations; (2) regional parties or organizations; and (3) sectoral parties

or organizations. National and regional parties or organizations are different from sectoral parties

or organizations. National and regional parties or organizations need not be organized along

sectoral lines and need not represent any particular sector.

Under the party-list system, an ideology-based or cause-oriented political party is clearly different

from a sectoral party. A political party need not be organized as a sectoral party and need not

represent any particular sector. There is no requirement in R.A. 7941 that a national or regional

political party must represent a "marginalized and underrepresented" sector. It is sufficient that the

political party consists of citizens who advocate the same ideology or platform, or the same

governance principles and policies, regardless of their economic status as citizens. While the major

political parties are those that field candidates in the legislative district elections. Major political

parties, however, cannot participate in the party-list elections since they neither lack "well-defined

political constituencies" nor represent "marginalized and underrepresented" sectors. Thus, the

national or regional parties under the party-list system are necessarily those that do not belong to

major political parties. This automatically reserves the national and regional parties under the

party-list system to those who "lack well-defined political constituencies," giving them the

opportunity to have members in the House of Representatives.

The Supreme Court cannot engage in socio-political engineering and judicially legislate the

exclusion of major political parties from the party-list elections in patent violation of the

Constitution and the law." The experimentations in socio-political engineering have only resulted in

confusion and absurdity in the party- list system. Such experimentations, in clear contravention of

the 1987 Constitution and R.A. 7941, must now come to an end. The High Court is sworn to uphold

the 1987 Constitution, apply its provisions faithfully, and desist from engaging in socio-economic or

Page 4 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

political experimentations contrary to what the Constitution has ordained. Judicial power does not

include the power to re-write the Constitution. Thus, in this case the Supreme Court remanded the

present petitions to the COMELEC not because the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion

in disqualifying petitioners, but because petitioners may now possibly qualify to participate in the

coming 13 May 2013 party-list elections under the new parameters prescribed by the Supreme

Court. ATONG PAGLAUM, INC., represented by its President, Mr. Alan Igot v. COMMISSION ON

ELECTIONS, G.R. No. 203766, April 2, 2013

POWERS OF CONGRESS

The House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal (HRET) has jurisdiction to pass upon the

qualifications of party-list nominees after their proclamation and assumption of office; they are, for

all intents and purposes, "elected members" of the House of Representatives. WALDEN F. BELLO

AND LORETTA ANN P. ROSALES v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, G.R. No. 191998, December

07, 2010

The power of the HRET, no matter how complete and exclusive, does not carry with it the authority

to delve into the legality of the judgment of naturalization in the pursuit of disqualifying

Limkaichong. To rule otherwise would operate as a collateral attack on the citizenship of the father

which is not permissible. RENALD F. VILANDO v. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL

TRIBUNAL, et al., G.R. Nos. 192147, August 23, 2011

The conferral of the legislative power of inquiry upon any committee of Congress, must carry with

it all powers necessary and proper for its effective discharge. PHILCOMSAT HOLDINGS

CORPORATION, et al. v. SENATE OF THE PHILIPPINES, et al., G.R. No. 180308, June 19, 2012

A person cannot file an action with the Supreme Court questioning the findings of the House of

Representatives Electoral Tribunal (HRET) except when it committed a grave abuse of discretion.

The abuse must, as contemplated by the law, be so gross that it amounts to evasion of duty. MARIA

LOURDES B. LOCSIN v. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL AND MONIQUE

YAZMIN MARIA Q. LAGDAMEO, G.R. No. 204123, March 19, 2013

The House of Representatives Electoral Tribunal was in no way estopped from subsequently

declaring that the integrity of the ballot boxes was not preserved opposed to its initial findings,

after it had the opportunity to exhaustively observe and examine in the course of the entire revision

proceedings the conditions of all the ballot boxes and their contents, including the ballots

themselves, the Minutes of Voting, Statements of Votes and Election Returns. LIWAYWAY

VINZONS-CHATO v. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL and ELMER E.

PANOTES, G.R. No. 204637, April 16, 2013

Section 17, Article VI of the 1987 Constitution, provides that the House of Representatives Electoral

Tribunal has the exclusive jurisdiction to be the "sole judge of all contests relating to the election,

returns and qualifications" of the Members of the House of Representatives. To be considered a

Member of the House of Representatives, there must be a concurrence of all of the following

requisites: (1) a valid proclamation; (2) a proper oath; and (3) assumption of office. Absent any of

the foregoing, the COMELEC retains jurisdiction over the said contests. REGINA ONGSIAKO REYES

v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS and JOSEPH SOCORRO B. TAN, G.R. No. 207264, June 25, 2013

Page 5 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

Congress has the power and prerogative to introduce substantial changes in the statutory public

office or position and to reclassify it as a primarily confidential, non-career service position.

Flowing from the legislative power to create public offices is the power to abolish and modify them

to meet the demands of society; Congress can change the qualifications for and shorten the term of

existing statutory offices. When done in good faith, these acts would not violate a public officers

security of tenure, even if they result in his removal from office or the shortening of his term.

Modifications in public office, such as changes in qualifications or shortening of its tenure, are made

in good faith so long as they are aimed at the office and not at the incumbent. THE PROVINCIAL

GOVERNMENT OF CAMARINES NORTE, represented by GOVERNOR JESUS O. TYPOCO, JR. v.

BEATRIZ O. GONZALES, G.R. No. 185740, July 23, 2013

The HRET is the sole judge of all contests relating to the election, returns and qualifications of the

Members of the House of Representatives. REGINA ONGSIAKO REYES v. COMMISSION ON

ELECTIONS AND JOSEPH SOCORRO B. TAN, G.R. No. 207264, October 22, 2013

Reapportionment is the realignment or change in legislative districts brought about by changes in

population and mandated by the constitutional requirement of equality of representation. The aim

of legislative apportionment is to equalize population and voting power among districts. The basis

for districting shall be the number of the inhabitants of a city or a province and not the number of

registered voters therein. The Court notes that after the reapportionment of the districts in

Camarines Sur, the current Third District, which brought Naval to office in 2010 and 2013, has a

population of 35,856 less than that of the old Second District, which elected him in 2004 and 2007.

However, the wordings of R.A. 9716 indicate the intent of the lawmakers to create a single new

Second District from the merger of the towns from the old First District with Gainza and Milaor. As

to the current Third District, Section 3 (c) of R.A. 9716 used the word rename. Although the

qualifier without a change in its composition was not found in Section 3(c), unlike in Sections 3(d)

and (e), still, what is pervasive is the clear intent to create a sole new district in that of the Second,

while merely renaming the rest. ANGEL G. NAVAL v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND NELSON

B. JULIA, G.R. No. 207851, July 8, 2014

LIMITATIONS ON LEGISLATIVE POWER

The Constitution requires Congress to stipulate in the Local Government Code all the criteria

necessary for the creation of a city, including the conversion of a municipality into a city. Congress

cannot write such criteria in any other law, like the Cityhood Laws. LEAGUE OF CITIES OF THE

PHILIPPINES v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 176951, August 24, 2010

R.A. 9646 does not violate the one title-one subject rule under Article VI, Section 26 (1) of the

Constitution. In Farinas v. Executive Secretary, the Court held it is sufficient if the title be

comprehensive enough reasonably to include the general object which a statute seeks to effect,

without expressing each and every end and means necessary or convenient to accomplish that

object. Aside from provisions establishing a regulatory system for the professionalization of the real

estate service sector, the new law extended its coverage to real estate developers with respect to

their own properties. The inclusion of real estate developers is germane to the laws primary goal of

developing "a corps of technically competent, responsible and respected professional real estate

service practitioners whose standards of practice and service shall be globally competitive and will

promote the growth of the real estate industry." REMMAN ENTERPRISES, INC. v. PROFESSIONAL

REGULATORY BOARD OF REAL ESTATE SERVICE, G.R. No. 197676; February 4, 2014

Page 6 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

PDAF

No question involving the constitutionality or validity of a law or governmental act may be heard

and decided by the Court unless there is compliance with the legal requisites for judicial inquiry,

namely: (a) there must be an actual case or controversy calling for the exercise of judicial power;

(b) the person challenging the act must have the standing to question the validity of the subject act

or issuance; (c) the question of constitutionality must be raised at the earliest opportunity; and (d)

the issue of constitutionality must be the very lis mota of the case. Legislators have been, in one

form or another, authorized to participate in the various operational aspects of budgeting,

including the evaluation of work and financial plans for individual activities and the regulation

and release of funds , in violation of the separation of powers principle [The Court cites its Decision

on Guingona, Jr. v. Carague (Guingona, Jr., 1991)]. From the moment the law becomes effective, any

provision of law that empowers Congress or any of its members to play any role in the

implementation or enforcement of the law violates the principle of separation of powers and is thus

unconstitutional [The Court cites its Decision on Abakada Guro Party List v. Purisima (Abakada,

2008)]. That the said authority is treated as merely recommendatory in nature does not alter its

unconstitutional tenor since the prohibition covers any role in the implementation or enforcement

of the law.

The 2013 PDAF Article violates the principle of non-delegability since legislators are effectively

allowed to individually exercise the power of appropriation, which is lodged in Congress. The

power to appropriate must be exercised only through legislation, pursuant to Section 29 (1), Article

VI of the 1987 Constitution. Under the 2013 PDAF Article, individual legislators are given a personal

lump-sum fund from which they are able to dictate (a) how much from such fund would go to; and

(b) a specific project or beneficiary that they themselves also determine. Since these two acts

comprise the exercise of the power of appropriation and given that the 2013 PDAF Article

authorizes individual legislators to perform the same, undoubtedly, said legislators have been

conferred the power to legislate which the Constitution does not, however, allow.

Under the 2013 PDAF Article, the amount of P24.79 Billion only appears as a collective allocation

limit since the said amount would be further divided among individual legislators who would then

receive personal lump-sum allocations and could, after the GAA is passed, effectively appropriate

PDAF funds based on their own discretion. As these intermediate appropriations are made by

legislators only after the GAA is passed and hence, outside of the law, it means that the actual items

of PDAF appropriation would not have been written into the General Appropriations Bill and thus

effectuated without veto consideration. This kind of lump-sum/post-enactment legislative

identification budgeting system fosters the creation of a budget within a budget which subverts the

prescribed procedure of presentment and consequently impairs the Presidents power of item veto.

As petitioners aptly point out, the President is forced to decide between (a) accepting the entire

P24. 79 Billion PDAF allocation without knowing the specific projects of the legislators, which may

or may not be consistent with his national agenda and (b) rejecting the whole PDAF to the

detriment of all other legislators with legitimate projects.

Even without its post-enactment legislative identification feature, the 2013 PDAF Article would

remain constitutionally flawed since the lump-sum amount of P24.79 Billion would be treated as a

mere funding source allotted for multiple purposes of spending (i.e., scholarships, medical missions,

assistance to indigents, preservation of historical materials, construction of roads, flood control,

etc). This setup connotes that the appropriation law leaves the actual amounts and purposes of the

appropriation for further determination and, therefore, does not readily indicate a discernible item

which may be subject to the Presidents power of item veto.

Page 7 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

To a certain extent, the conduct of oversight would be tainted as said legislators, who are vested

with post-enactment authority, would, in effect, be checking on activities in which they themselves

participate. Also, this very same concept of post-enactment authorization runs afoul of Section 14,

Article VI of the 1987 Constitution which provides that: [A Senator or Member of the House of

Representatives] shall not intervene in any matter before any office of the Government for his

pecuniary benefit or where he may be called upon to act on account of his office. Allowing

legislators to intervene in the various phases of project implementation renders them susceptible

to taking undue advantage of their own office.

Section 26, Article II of the 1987 Constitution is considered as not self-executing due to the

qualifying phrase as may be defined by law. In this respect, said provision does not, by and of

itself, provide a judicially enforceable constitutional right but merely specifies a guideline for

legislative or executive action.

The Court, however, finds an inherent defect in the system which actually belies the avowed

intention of making equal the unequal (Philippine Constitution Association v. Enriquez, G.R. No.

113105, August 19, 1994). The gauge of PDAF and CDF allocation/division is based solely on the

fact of office, without taking into account the specific interests and peculiarities of the district the

legislator represents. As a result, a district representative of a highly-urbanized metropolis gets the

same amount of funding as a district representative of a far-flung rural province which would be

relatively underdeveloped compared to the former. To add, what rouses graver scrutiny is that

even Senators and Party-List Representatives and in some years, even the Vice-President who

do not represent any locality, receive funding from the Congressional Pork Barrel as well.

Considering that Local Development Councils are instrumentalities whose functions are essentially

geared towards managing local affairs, their programs, policies and resolutions should not be

overridden nor duplicated by individual legislators, who are national officers that have no lawmaking authority except only when acting as a body.

Regarding the Malampaya Fund: The phrase and for such other purposes as may be hereafter

directed by the President under Section 8 of P.D. 910 constitutes an undue delegation of legislative

power insofar as it does not lay down a sufficient standard to adequately determine the limits of the

Presidents authority with respect to the purpose for which the Malampaya Funds may be used. As

it reads, the said phrase gives the President wide latitude to use the Malampaya Funds for any other

purpose he may direct and, in effect, allows him to unilaterally appropriate public funds beyond the

purview of the law.

As for the Presidential Social Fund: Section 12 of P.D. 1869, as amended by P.D. 1993, indicates that

the Presidential Social Fund may be used to [first,] finance the priority infrastructure

development projects and [second,] to finance the restoration of damaged or destroyed facilities

due to calamities, as may be directed and authorized by the Office of the President of the

Philippines.

The second indicated purpose adequately curtails the authority of the President to spend the

Presidential Social Fund only for restoration purposes which arise from calamities. The first

indicated purpose, however, gives him carte blanche authority to use the same fund for any

infrastructure project he may so determine as a priority. Verily, the law does not supply a definition

of priority infrastructure development projects and hence, leaves the President without any

guideline to construe the same. To note, the delimitation of a project as one of infrastructure is too

Page 8 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

broad of a classification since the said term could pertain to any kind of facility. Thus, the phrase to

finance the priority infrastructure development projects must be stricken down as

unconstitutional since similar to Section 8 of P.D. 910 it lies independently unfettered by any

sufficient standard of the delegating law. BELGICA et al. v. OCHOA JR.; SJS v. DRILON et al.;

NEPOMUCENO v. PRESIDENT AQUINO III, G.R. No. 208566, G.R. No. 208493, G.R. No. 209251,

November 19, 2013

DISBURSEMENT ACCELERATION PROGRAM

The DAP was a government policy or strategy designed to stimulate the economy through

accelerated spending. In the context of the DAPs adoption and implementation being a function

pertaining to the Executive as the main actor during the Budget Execution Stage under its

constitutional mandate to faithfully execute the laws, including the GAAs, Congress did not need to

legislate to adopt or to implement the DAP. Congress could appropriate but would have nothing

more to do during the Budget Execution Stage.

The President, in keeping with his duty to faithfully execute the laws, had sufficient discretion

during the execution of the budget to adapt the budget to changes in the countrys economic

situation. He could adopt a plan like the DAP for the purpose. He could pool the savings and identify

the PAPs to be funded under the DAP. The pooling of savings pursuant to the DAP, and the

identification of the PAPs to be funded under the DAP did not involve appropriation in the strict

sense because the money had been already set apart from the public treasury by Congress through

the GAAs. In such actions, the Executive did not usurp the power vested in Congress under Section

29(1), Article VI of the Constitution.

The transfer of appropriated funds, to be valid under Section 25 (5) must be made upon a

concurrence of the following requisites, namely:

1. There is a law authorizing the President, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the

House of Representatives, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and the heads of the

Constitutional Commissions to transfer funds within their respective offices;

2. The funds to be transferred are savings generated from the appropriations for their

respective offices; and

3. The purpose of the transfer is to augment an item in the general appropriations law for

their respective offices.

Savings refer to portions or balances of any programmed appropriation in this Act free from any

obligation or encumbrance which are: (i) still available after the completion or final discontinuance

or abandonment of the work, activity or purpose for which the appropriation is authorized; (ii)

from appropriations balances arising from unpaid compensation and related costs pertaining to

vacant positions and leaves of absence without pay; and (iii) from appropriations balances realized

from the implementation of measures resulting in improved systems and efficiencies and thus

enabled agencies to meet and deliver the required or planned targets, programs and services

approved in this Act at a lesser cost.

The DBM declares that part of the savings brought under the DAP came from "pooling of unreleased

appropriations such as unreleased Personnel Services appropriations which will lapse at the end of

the year, unreleased appropriations of slow moving projects and discontinued projects per ZeroBased Budgeting findings." The declaration of the DBM by itself does not state the clear legal basis

for the treatment of unreleased or unalloted appropriations as savings. The fact alone that the

appropriations are unreleased or unalloted is a mere description of the status of the items as

Page 9 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

unalloted or unreleased. They have not yet ripened into categories of items from which savings can

be generated. Appropriations have been considered "released" if there has already been an

allotment or authorization to incur obligations and disbursement authority.

Congress acts as the guardian of the public treasury in faithful discharge of its power of the purse

whenever it deliberates and acts on the budget proposal submitted by the Executive. Its power of

the purse is touted as the very foundation of its institutional strength, and underpins "all other

legislative decisions and regulating the balance of influence between the legislative and executive

branches of government." Such enormous power encompasses the capacity to generate money for

the Government, to appropriate public funds, and to spend the money. Pertinently, when it

exercises its power of the purse, Congress wields control by specifying the PAPs for which public

money should be spent.

It is the President who proposes the budget but it is Congress that has the final say on matters of

appropriations. For this purpose, appropriation involves two governing principles, namely: (1) "a

Principle of the Public Fisc, asserting that all monies received from whatever source by any part of

the government are public funds;" and (2) "a Principle of Appropriations Control, prohibiting

expenditure of any public money without legislative authorization." To conform with the governing

principles, the Executive cannot circumvent the prohibition by Congress of an expenditure for a

PAP by resorting to either public or private funds. Nor could the Executive transfer appropriated

funds resulting in an increase in the budget for one PAP, for by so doing the appropriation for

another PAP is necessarily decreased. The terms of both appropriations will thereby be violated.

MARIA CAROLINA P. ARAULLO v. BENIGNO SEMION C. AQUINO III, G.R. No. 209287, July 1,

2014

CYBERCRIME LAW

Section 4 (c) (3) Penalizing posts of unsolicited commercial communications or SPAM. Unsolicited

advertisements are legitimate forms of expression. Commercial speech though not accorded the

same level of protection as that given to other constitutionally guaranteed forms of expression; it is

nonetheless entitled to protection. The State cannot rob one of these rights without violating the

constitutionally guaranteed freedom of expression.

Section 12 Authorizing the collection or recording of traffic data in real-time. If such would be

granted to law enforcement agencies it would curtail civil liberties or provide opportunities for

official abuse. Section 12 is too broad and do not provide ample safeguards against crossing legal

boundaries and invading the right to privacy.

Informational Privacy which is the interest in avoiding disclosure of personal matters has two

aspects, specifically: (1) The right not to have private information disclosed; and (2) The right to

live freely without surveillance and intrusion.

Section 12 applies to all information and communications technology users and transmitting

communications is akin to putting a letter in an envelope properly addressed, sealing it closed and

sending it through the postal service.

Another reason to strike down said provision is by reason that it allows collection and recording

traffic data with due cause. Section 12 does not bother to relate the collection of data to the

probable commission of a particular crime. It is akin to the use of a general search warrant that the

Constitution prohibits. Likewise it is bit descriptive of the purpose for which data collection will be

Page 10 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

used. The authority given is too sweeping and lacks restraint which may only be used for Fishing

Expeditions and unnecessarily expose the citizenry to leaked information or worse to extortion

from certain bad elements in these agencies.

Section 19 Authorizing the DOJ to restrict or block access to suspected computer data. Computer

data produced by its author constitutes personal property regardless of where it is stored. The

provision grants the Government the power to seize and place the computer data under its control

and disposition without a warrant. The DOJ order cannot substitute

judicial search warrants.

Content of the computer data also constitutes speech which is entitled to protection. If an executive

officer could be granted such power to acquire data without warrants and declare that its content

violates the law that would make him the judge, jury and executioner all rolled in one.

Section 19 also disregards jurisprudential guidelines established to determine the validity of

restrictions on speech: (1) dangerous tendency doctrine; (2) balancing of interest test; and (3) clear

and present danger rule.

It merely requires that the data be blocked if on its face it violate any provision of the cybercrime

law.

Section 4 (c) (4) penalizes libel in connection with Section 5 which penalizes aiding or abetting to

said felony. Section 4 (c) (4) is valid and constitutional with respect to the original author of the

post but void and unconstitutional with respect to other who simply receive the post and react to it.

With regard to the author of the post, Section 4 (c) (4) merely affirms that online defamation

constitutes similar means for committing libel as defined under the RPC.

The internet encourages a freewheeling, anything-goes writing style. Facebook and Twitter were

given as examples and stated that the acts of liking, commenting, sharing or re-tweets, are not

outrightly considered to be aiding or abetting. Compared to the physical world such would be mere

expressions or reactions made regarding a specific post.

The terms aiding or abetting constitute a broad sweep that generates a chilling effect on those

who express themselves through cyberspace posts, comments, and other messages.

If such means are adopted, self-inhibition borne of fear of what sinister predicament awaits

internet users will suppress otherwise robust discussion of public issues and democracy will be

threatened together with all liberties.

Charging offenders of violation of R.A. 10175 and the RPC both with regard to libel and likewise

with R.A. 9775 on Child pornography constitutes double jeopardy. The acts defined in the

Cybercrime Law involve essentially the same elements and are in fact one and the same with the

RPC and R.A. 9775. JOSE JESUS M. DISINI, Jr., ET AL v. THE SECRETARY OF JUSTICE, ET AL., G.R.

No. 203335. February 18, 2014

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT

Page 11 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

The doctrine of command responsibility is a rule of substantive law that establishes liability and, by

this account, cannot be a proper legal basis to implead a party-respondent in an amparo petition. IN

THE MATTER OF THE PETITION FOR THE WRIT OF AMPARO AND THE WRIT OF HABEAS

DATA IN FAVOR OF MELISSA C. ROXAS, MELISSA C. ROXAS v. GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO,

et al., G.R. No. 189155, September 07, 2010

The doctrine of state immunity should not be extended to the petitioner as the same is an agency of

the Government not performing a purely governmental or sovereign function, but was instead

involved in the management and maintenance of the Loakan Airport, an activity that was not the

exclusive prerogative of the State in its sovereign capacity. AIR TRANSPORTATION OFFICE v.

SPOUSES DAVID and ELISEA RAMOS, G.R. No. 159402, February 23, 2011

The president, as commander-in-chief of the military, can be held responsible or accountable for

extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances. IN THE MATTER OF THE PETITION FOR THE

WRIT OF AMPARO AND HABEAS DATA IN FAVOR OF NORIEL H. RODRIGUEZ, NORIEL H.

RODRIGUEZV. GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO, et al., G.R. No. 191805, 193160, November 15,

2011

POWERS

The President's act of delegating authority to the Secretary of Justice by virtue of Memorandum

Circular (MC) No. 58 is well within the purview of the doctrine of qualified political agency. JUDGE

ADORACION G. ANGELES v. HON. MANUEL E. GAITE et al., G.R. No. 176596, March 23, 2011

The President did not proclaim a national emergency, only a state of emergency. The calling out of

the armed forces to prevent or suppress lawless violence in such places is a power that the

Constitution directly vests in the President, without need of congressional authority to exercise the

same. DATU ZALDY UY AMPATUAN, et al. v. HON. RONALDO PUNO, et al., G.R. No. 190259,

June 7, 2011

The abolition of the PAGC and the transfer of its functions to a division specially created within the

ODESLA is properly within the prerogative of the President under his continuing delegated

legislative authority to reorganize his own office pursuant to Executive Order No (E.O.) 292.

PROSPERO A. PICHAY, JR. v. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY EXECUTIVE SECRETARY FOR LEGAL

AFFAIRS-INVESTIGATIVE AND ADJUDICATORY DIVISION, et al., G.R. NO. 196425, JULY 24,

2012

Directives and orders issued by the President in the valid exercise of his power of control over the

executive department must be obeyed and implemented in good faith by all executive officials. Acts

performed in contravention of such directives merit invalidation. DR. EMMANUEL T. VELASCO, et

al. v. COMMISSION ON AUDIT AND THE DIRECTOR, NATIONAL GOVERNMENT AUDIT OFFICE,

G.R. No. 189774, September 18, 2012

The Presidents discretion in the conferment of the Order of National Artists should be exercised in

accordance with the duty to faithfully execute the relevant laws. The faithful execution clause is

best construed as an obligation imposed on the President, not a separate grant of power. It simply

underscores the rule of law and, corollarily, the cardinal principle that the President is not above

the laws but is obliged to obey and execute them. This is precisely why the law provides that

"administrative or executive acts, orders and regulations shall be valid only when they are not

Page 12 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

contrary to the laws or the Constitution." NATIONAL ARTIST FOR LITERATURE VIRGILIO

ALMARIO, et al. v. THE EXECUTIVE SECRETARY, et al., G.R. No. 189028, July 16, 2013

It is apparent from the foregoing constitutional provisions that the only instances in which the

President may not extend pardon remain to be in: (1) impeachment cases; (2) cases that have not

yet resulted in a final conviction; and (3) cases involving violations of election laws, rules and

regulations in which there was no favorable recommendation coming from the COMELEC.

Therefore, it can be argued that any act of Congress by way of statute cannot operate to delimit the

pardoning power of the President. ATTY. ALICIA RISOS-VIDAL v. ALFREDO LIM, G.R. No.

206666, January 21, 2015

The doctrine of qualified political agency declares that, save in matters on which the Constitution or

the circumstances require the President to act personally, executive and administrative functions

are exercised through executive departments headed by cabinet secretaries, whose acts are

presumptively the acts of the President unless disapproved by the latter. There can be no question

that the act of the secretary is the act of the President, unless repudiated by the latter. In this case,

approval of the Amendments to the Supplemental Toll Operation Agreement (ASTOA) by the DOTC

Secretary had the same effect as approval by the President. The same would be true even without

the issuance of E.O. 497, in which the President specifically delegated to the DOTC Secretary the

authority to approve contracts entered into by the Toll Regulatory Board. ANA THERESIA RISA

HONTIVEROS-BARAQUEL v. TOLL REGULATORY BOARD, G.R. No. 181293, February 23, 2015

POWER OF APPOINTMENT

The power to appoint rests essentially on free choice. The appointing authority has the right to

decide who best fits the job from among those who meet the minimum requirements for it. As an

outsider, quite remote from the day-to-day problems of a government agency, no court of law can

presume to have the wisdom needed to make a better judgment respecting staff appointments.

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT (DOLE) AND NATIONAL MARITIME

POLYTECHNIC (NMP) v. RUBEN Y. MACEDA, G.R. No. 185112, January 18, 2010

Prohibition against the President or Acting President making appointments within two months

before the next presidential elections and up to the end of the Presidents or Acting Presidents

term does not refer to the Members of the Supreme Court. ARTURO DE CASTRO v. JUDICIAL AND

BAR COUNCIL AND PRES. GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO, G. R. No. 191002, March 17, 2010

The prohibition against the President or Acting President to make appointments within two months

before the next presidential elections and up to the end of the Presidents or Acting Presidents

term does not refer to the Members of the Supreme Court. ARTURO M. DE CASTRO v. JUDICIAL

AND BAR COUNCIL AND PRESIDENT GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO, G. R. No. 191002, April

20, 2010

POWER OF CONTROL AND SUPERVISION

The Office of the President has jurisdiction to exercise administrative disciplinary power including

the power to dismiss a Deputy Ombudsman and a Special Prosecutor who belong to the

constitutionally- created Office of the Ombudsman. EMILIO A. GONZALES III v. OFFICE OF THE

PRESIDENT OF THE PHILIPPINES et al., G.R. Nos. 196231, 196232 September 04, 2012

POWERS RELATIVE TO APPROPRIATION MEASURES

Page 13 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

The power of the President to reorganize the Executive Branch includes such powers and functions

that may be provided for under other laws. To be sure, an inclusive and broad interpretation of the

Presidents power to reorganize executive offices has been consistently supported by specific

provisions in general appropriations laws. ATTY. SYLVIA BANDA et al. v. EDUARDO R. ERMITA,

G.R. No. 166620, April 20, 2010

JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT

JUDICIAL POWER

The issuance of subsequent resolutions by the Court is simply an exercise of judicial power under

Article VIII of the Constitution, because the execution of the Decision is but an integral part of the

adjudicative function of the Court. METROPOLITAN MANILA DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY v.

CONCERNED RESIDENTS OF MANILA BAY, G.R. Nos. 171947-48, February 15, 2011

Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) is not simply an agency to which Members of the Court were

designated. Once again, the PET, as intended by the framers of the Constitution, is to be an

institution independent, but not separate, from the judicial department, i.e., the Supreme Court.

ATTY. ROMULO B. MACALINTAL v. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL, G.R. No. 191618,

June 7, 2011

The fact that the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) conducts public

consultations or hearings does not mean that it is performing quasi-judicial functions. SALVACION

VILLANUEVA, et al. v. PALAWAN COUNCIL FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, et al., G.R. No.

178347, February 25, 2013

The Constitutional mandate of the courts in our triangular system of government is clear, so that as

a necessary requisite of the exercise of judicial power there must be, with a few exceptions, an

actual case or controversy involving a conflict of legal rights or an assertion of opposite legal claims

susceptible of judicial resolution, not merely a hypothetical or abstract difference or dispute. As

Article VIII, Section 1 of the 1987 Constitution provides, "judicial power includes the duty of the

courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and

enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting

to lack or excess of jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government."

The power of judicial review is limited to actual cases or controversies. Courts decline to issue

advisory opinions or to resolve hypothetical or feigned problems, or mere academic questions. The

limitation of the power of judicial review to actual cases and controversies defines the role assigned

to the judiciary in a tripartite allocation of power, to assure that the courts will not intrude into

areas committed to the other branches of government. PHILIPPINE AMUSEMENT AND GAMING

CORPORATION v. THUNDERBIRD PILIPINAS HOTELS AND RESORTS, INC., et al., G.R. No.

197942-43/G.R. No. 199528. March 26, 2014

The interpretation and application of laws have been assigned to the Judiciary under our system of

constitutional government. Indeed, defining and interpreting the laws are truly a judicial function.

Hence, the Court of Appeals (CA) could not be denied the authority to interpret the provisions of the

articles of incorporation and bylaws of Forest Hills, because such provisions, albeit in the nature of

Page 14 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

private laws, have an impact on the definition of the rights and obligations of the parties. FOREST

HILLS GOLF AND COUNTRY CLUB, INC., v. GARDPRO, INC., G.R. No. 164686, October 22, 2014

JUDICIAL REVIEW

Judicial review is permitted if the courts believe that there is substantial evidence supporting the

claim of citizenship, so substantial that there are reasonable grounds for the belief that the claim is

correct. When the evidence submitted by a deportee is conclusive of his citizenship, the right to

immediate review should be recognized and the courts should promptly enjoin the deportation

proceedings. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE SECRETARY RAUL GONZALEZ, et al. v. MICHAEL ALFIO

PENNISI, G.R. No. 169958, March 5, 2010

The discretion to determine whether a case should be filed or not lies with the Ombudsman. Unless

grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction is shown, judicial review is

uncalled for as a policy of non-interference by the courts in the exercise of the Ombudsmans

constitutionally mandated powers. ANGELITA DE GUZMAN v. EMILIO A. GONZALEZ III, et al., G.R.

No. 158104, March 26, 2010

Unless it is shown that the questioned acts were done in a capricious and whimsical exercise of

judgment evidencing a clear case of grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of

jurisdiction, this Court will not interfere in the findings of probable cause determined by the

Ombudsman. ROBERTO B. KALALO v. OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN, ERNESTO M. DE CHAVEZ

AND MARCELO L. AGUSTIN, G.R. No. 158189, April 23, 2010

The Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) was constituted in implementation of Section 4, Article

VII of the Constitution, and it faithfully complies - not unlawfully defies - the constitutional

directive. As intended by the framers of the Constitution, is to be an institution independent, but not

separate, from the judicial department, i.e., the Supreme Court. ATTY. ROMULO B. MACALINTAL v.

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTORAL TRIBUNAL, G.R. No. 191618, November 23, 2010

When the issues presented do not require the expertise, specialized skills, and knowledge of a body

but are purely legal questions which are within the competence and jurisdiction of the Court, the

doctrine of primary jurisdiction should not be applied. AQUILINO Q. PIMENTEL, JR., et al. v.

SENATE COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE REPRESENTED BY SENATE PRESIDENT JUAN PONCE

ENRILE, G.R. No. 187714, March 08, 2011

The determination of where, as between two possible routes, to construct a road extension is

obviously not within the province of this Court. Such determination belongs to the Executive

branch. BARANGAY CAPTAIN BEDA TORRECAMPO v. METROPOLITAN WATERWORKS AND

SEWERAGE SYSTEM, et al., G.R. No. 188296, May 30, 2011

Certiorari does not lie against the Sangguniang Panglungsod, which was not a part of the Judiciary

settling an actual controversy involving legally demandable and enforceable rights when it adopted

Resolution No. 552, but a legislative and policy-making body declaring its sentiment or opinion.

SPOUSES ANTONIO AND FE YUSAY v. COURT OF APPEALS, CITY MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL

OF MANDALUYONG CITY, G.R. No. 156684, April 06, 2011

This Court has no power to review via certiorari an interlocutory order or even a final resolution of

a division of the COMELEC. However, the Court held that an exception to this rule applies where the

Page 15 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

commission of grave abuse of discretion is apparent on its face. MARIA LAARNI L. CAYETANO v.

THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND DANTE O. TINGA, G.R. No. 193846, April 12, 2011

While as a rule, it is beyond the province of the Court to analyze and weigh the parties evidence all

over again in reviewing administrative decisions, an exception thereto lies as when there is serious

ground to believe that a possible miscarriage of justice would thereby result. OFFICE OF THE

OMBUDSMAN v. ANTONIO T. REYES G.R. No. 170512, October 5, 2011

The power of judicial review in this jurisdiction includes the power of review over justiciable issues

in impeachment proceedings. CHIEF JUSTICE RENATO C. CORONA v. SENATE OF THE

PHILIPPINES SITTING AS AN IMPEACHMENT COURT, et al., G.R. No. 200242, July 17, 2012

Courts cannot certainly give primacy to matters of procedure over substance in a party-list groups

Constitution and By-Laws, especially after the general membership has spoken. SAMSON S.

ALCANTARA, ROMEO R. ROBJSO, PEDRO T. DABU, JR., LOPE E. FEBLE, NOEL T. TIAMPONG and

JOSE FLORO CRISOLOGO v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, JONATHAN DE LA CRUZ, ED

VINCENT ALBANO and BENEDICT KATO, G.R. No. 203646, April 16, 2013

Where the respondent is absolved of the charge, and in case of conviction where the penalty

imposed is public censure or reprimand, suspension of not more than one month, or a fine

equivalent to one month salary, the Ombudsmans decision shall be final, executory, and

unappealable. But of course, the said principle is subject to the rule that decisions of administrative

agencies which are declared final and unappealable by law are still "subject to judicial review if

they fail the test of arbitrariness, or upon proof of grave abuse of discretion, fraud or error of law,

or when such administrative or quasi-judicial bodies grossly misappreciate evidence of such nature

as to compel a contrary conclusion, the Court will not hesitate to reverse the factual findings."

FREDERICK JAMES C. ORAlS v. DR. AMELIA C. ALMIRANTE, G.R. No. 181195, June 10, 2013

An actual case or controversy involves a conflict of legal rights, an assertion of opposite legal claims

susceptible to judicial resolution. Petitioners who are real estate developers are entities directly

affected by the prohibition on performing acts constituting practice of real estate service without

first complying with the registration and licensing requirements for brokers and agents under R.A.

9646. The possibility of criminal sanctions for disobeying the mandate of the new law is likewise

real. Asserting that the prohibition violates their rights as property owners, petitioners challenged

on constitutional grounds the laws implementation which respondents defended as a valid

legislation pursuant to police power. REMMAN ENTERPRISES, INC. v. PROFESSIONAL

REGULATORY BOARD OF REAL ESTATE SERVICE, G.R. No. 197676; February 4, 2014

Constitution requires our courts to conscientiously observe the time periods in deciding cases and

resolving matters brought to their adjudication, which, for lower courts, is three (3) months from

the date they are deemed submitted for decision or resolution. SPOUSES RICARDO and EVELYN

MARCELO v. JUDGE RAMSEY DOMINGO G. PICHAY, METROPOLITAN TRIAL COURT, BRANCH

78, PARANAQUE CITY, A.M. No. MTJ-13-1838, March 12, 2014

What further constrains this Court from touching on the issue of constitutionality is the fact that

this issue is not the lis mota of this case. Lis mota literally means the cause of the suit or action; it

is rooted in the principle of separation of powers and is thus merely an offshoot of the presumption

of validity accorded the executive and legislative acts of our coequal branches of the government.

KALIPUNAN NG DAMAYANG MAHIHIRAP, INC., v. JESSIE ROBREDO, G.R. No. 200903, July 22,

2014

Page 16 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

The petition did not comply with the requisites of judicial review as there was no actual case or

controversy. Petitioner's allegations show that he wants the Supreme Court to strike down the

proposed bills abolishing the Judiciary Development Fund. This court must act only within its

powers granted under the Constitution. This court is not empowered to review proposed bills

because a bill is not a law. The court has explained that the filing of bills is within the legislative

power of Congress and is not subject to judicial restraint. Under the Constitution, the judiciary is

mandated to interpret laws. It cannot speculate on the constitutionality or unconstitutionality of a

bill that Congress may or may not pass. It cannot rule on mere speculations or issues that are not

ripe for judicial determination. The petition, therefore, does not present any actual case or

controversy that is ripe for this court's determination. IN THE MATTER OF: SAVE THE SUPREME

COURT JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE AGAINST THE ABOLITION OF THE JUDICIARY

DEVELOPMENT FUND (JDF) AND REDUCTION OF AUTONOMY, UDK-15143; January 21, 2015

The following are the determinants of an issue having transcendental importance: (a) the character

of the funds or other assets involved in the case; (b) the presence of a clear case of disregard of a

constitutional or statutory prohibition by the public respondent agency or instrumentality of the

government; and (c) the lack of any other party with a more direct and specific interest in raising

the questions being raised. None of the determinants is present in this case. The events feared by

petitioner are merely speculative. IN THE MATTER OF: SAVE THE SUPREME COURT JUDICIAL

INDEPENDENCE AGAINST THE ABOLITION OF THE JUDICIARY DEVELOPMENT FUND (JDF)

AND REDUCTION OF AUTONOMY, UDK-15143, January 21, 2015

OPERATIVE FACT DOCTRINE

The operative fact doctrine is not confined to statutes and rules and regulations issued by the

executive department that are accorded the same status as that of a statute or those which are

quasi-legislative in nature. HACIENDA LUISITA, INCORPORATED et.al v. PRESIDENTIAL

AGRARIAN REFORM COUNCIL, G.R. No. 171101, November 22, 2011

As a general rule, the nullification of an unconstitutional law or act carries with it the illegality of its

effects. However, in cases where nullification of the effects will result in inequity and injustice, the

operative fact doctrine may apply. The Court has upheld the efficacy of such DAP-funded projects

by applying the operative fact doctrine. MARIA CAROLINA P. ARAULLO v. BENIGNO SEMION C.

AQUINO III, G.R. No. 209287, July 1, 2014

MOOT & ACADEMIC

As a rule, this Court may only adjudicate actual, ongoing controversies. The Court is not empowered

to decide moot questions or abstract propositions, or to declare principles or rules of law which

cannot affect the result as to the thing in issue in the case before it. In other words, when a case is

moot, it becomes non-justiciable. ATTY. EVILLO C. PORMENTO v. JOSEPH "ERAP" EJERCITO

ESTRADA AND COMELEC, G.R. No. 191988, August 31, 2010

E.O. 883 and Career Executive Service Board Resolution No. 870 having ceased to have any force

and effect, the Court can no longer pass upon the issue of their constitutionality. ATTY. ELIAS

OMAR A. SANA v. CAREER EXECUTIVE SERVICE BOARD, G.R. No. 192926, November 15, 2011

Page 17 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

A case becomes moot and academic when there is no more actual controversy between the parties

or no useful purpose can be served in passing upon the merits. JOEL P. QUIO, et al. v.

COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND RITCHIE R. WAGAS, G.R. No. 197466, November 13, 2012

Retirement from the service during the pendency of an administrative case does not render the

case moot and academic. OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN v. MARCELINO A. DECHAVEZ, G.R. No.

176702, November 13, 2013

The power of judicial review is limited to actual cases or controversies. The Court, as a rule, will

decline to exercise jurisdiction over a case and proceed to dismiss it when the issues posed have

been mooted by supervening events. Mootness intervenes when a ruling from the Court no longer

has any practical value and, from this perspective, effectively ceases to be a justiciable controversy.

While the Court has recognized exceptions in applying the "moot and academic" principle, these

exceptions relate only to situations where: (1) there is a grave violation of the Constitution; (2) the

situation is of exceptional character and paramount public interest is involved; (3) the

constitutional issue raised requires formulation of controlling principles to guide the bench, the

bar, and the public; and (4) the case is capable of repetition yet evading review. BANKERS

ASSOCIATION OF THE PHILIPPINES and PERRY L. PE v. THE COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS, G.R.

No. 206794, November 26, 2013

For a court to exercise its power of adjudication, there must be an actual case or controversy. Thus,

in Mattel, Inc. v. Francisco we have ruled that "where the issue has become moot and academic,

there is no justiciable controversy, and adjudication thereof would be of no practical use or value as

courts do not sit to adjudicate mere academic questions to satisfy scholarly interest however

intellectually challenging." HADJI HASHIM ABDUL v. HONORABLE SANDIGANBAYAN (FIFTH

DIVISION) and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, G.R. NO. 184496, December 2, 2013

POLITICAL QUESTION DOCTRINE

The constitutional validity of the Presidents proclamation of martial law or suspension of the

privilege of the writ of habeas corpus is first a political question in the hands of Congress before it

becomes a justiciable one in the hands of the Court. PHILIP SIGFRID A. FORTUN AND ALBERT

LEE G. ANGELES v. GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO, AS COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF AND

PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, et al., G.R. No. 190293, March 20, 2012

As stated in Francisco v. HRET, a political question will not be considered justiciable if there are no

constitutionally-imposed limits on powers or functions conferred upon political bodies. Hence, the

existence of constitutionally-imposed limits justifies subjecting the official actions of the body to the

scrutiny and review of this court. In this case, the Bill of Rights gives the utmost deference to the

right to free speech. Any instance that this right may be abridged demands judicial scrutiny. It does

not fall squarely into any doubt that a political question brings. THE DIOCESE OF BACOLOD,

REPRESENTED BY THE MOST REV. BISHOP VICENTE M. NAVARRA and THE BISHOP HIMSELF

IN HIS PERSONAL CAPACITY v. COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS AND THE ELECTION OFFICER OF

BACOLOD CITY, ATTY. MAVIL V. MAJARUCON, G.R. No. 205728, January 21, 2015

APPOINTMENT TO THE JUDICIARY

For purposes of appointments to the judiciary, the date the commission has been signed by the

President (which is the date appearing on the face of such document) is the date of the

Page 18 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

appointment. Such date will determine the seniority of the members of the CA in connection with

Section 3, Chapter I of BP 129, as amended by R.A. 8246. RE: SENIORITY AMONG THE FOUR (4)

MOST RECENT APPOINTMENTS TO THE POSITION OF ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE COURT

OF APPEALS, A.M. No. 10-4-22-SC, September 28, 2010

The Constitution mandates that the JBC be composed of seven (7) members only. Thus, any

inclusion of another member, whether with one whole vote or half (1/2) of it, goes against that

mandate. FRANCISCO I. CHAVEZ v. JUDICIAL AND BAR COUNCIL, et al., G.R. NO. 202242, July

17, 2012

A reading of the 1987 Constitution would reveal that several provisions were indeed adjusted as to

be in tune with the shift to bicameralism. It is also very clear that the Framers were not keen on

adjusting the provision on congressional representation in the JBC because it was not in the

exercise of its primary function to legislate. In the creation of the JBC, the Framers arrived at a

unique system by adding to the four (4) regular members, three (3) representatives from the major

branches of government. In so providing, the Framers simply gave recognition to the Legislature,

not because it was in the interest of a certain constituency, but in reverence to it as a major branch

of government. Hence, the argument that a senator cannot represent a member of the House of

Representatives in the JBC and vice-versa is, thus, misplaced. In the JBC, any member of Congress,

whether from the Senate or the House of Representatives, is constitutionally empowered to

represent the entire Congress. FRANCISCO I. CHAVEZ v. JUDICIAL AND BAR COUNCIL, SEN.

FRANCIS JOSEPH G. ESCUDERO and REP. NIEL C. TUPAS, JR., G.R. No. 202242, April 16, 2013

Section 2, Rule 10 of JBC-009 envisions only a situation where an applicants moral fitness is

challenged. It follows then that the unanimity rule only comes into operation when the moral

character of a person is put in issue. It finds no application where the question is essentially

unrelated to an applicants moral uprightness. FRANCIS H. JARDELEZA v. CHIEF JUSTICE MARIA

LOURDES P. A. SERENO, G.R. No. 213181, August 19, 2014

The JBC, as a body, is not required by law to hold hearings on the qualifications of the nominees.

The process by which an objection is made based on Section 2, Rule 10 of JBC-009 is not judicial,

quasi-judicial, or fact-finding, for it does not aim to determine guilt or innocence akin to a criminal

or administrative offense but to ascertain the fitness of an applicant vis--vis the requirements for

the position. Being sui generis, the proceedings of the JBC do not confer the rights insisted upon by

Jardeleza. He may not exact the application of rules of procedure which are, at the most,

discretionary or optional. Finally, Jardeleza refused to shed light on the objections against him.

During the June 30, 2014 meeting, he did not address the issues, but instead chose to tread on his

view that the Chief Justice had unjustifiably become his accuser, prosecutor and judge. FRANCIS H.

JARDELEZA v. CHIEF JUSTICE MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO, G.R. No. 213181, August 19,

2014

CONSTITUTIONAL COMMISSIONS

THE COMMISSION OF AUDIT

POWERS

The Commission on Audit (COA) has been granted by the Constitution the authority to establish a

special audit group when a transaction warrants the formulation of the same and the authority to

Page 19 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

determine the scope of its audit and examination as well as the methods and techniques to be used

therefor. THE SPECIAL AUDIT TEAM, COMMISSION ON AUDIT v. COURT OF APPEALS and

GOVERNMENT SERVICE INSURANCE SYSTEM, G.R. No. 174788, April 11, 2013

No money shall be paid out of the Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation made by law.

The Constitution vests COA, as guardian of public funds, with enough latitude to determine, prevent

and disallow irregular, unnecessary, excessive, extravagant or unconscionable expenditures of

government funds. The COA is generally accorded complete discretion in the exercise of its

constitutional duty and the Court generally sustains its decisions in recognition of its expertise in

the laws it is entrusted to enforce.

On the issue whether the TESDA officials should refund the excess EME granted to them, the Court

applied the ruling in the case Casal v. COA where the Court held that the approving officials are

liable for the refund of the incentive award due to their patent disregard of the law of and the

directives of COA. Accordingly, the Director-General's blatant violation of the clear provisions of the

Constitution, the 2004- 2007 GAAs and the COA circulars is equivalent to gross negligence

amounting to bad faith. He is required to refund the EME he received from the TESDP Fund for

himself. TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY v. THE

COMMISSION ON AUDIT CHAIRPERSON MA. GRACIA PULIDO TAN, COMMISSIONER JUANITO

G. ESPINO, JR. AND COMMISSIONER HEIDI L. MENDOZA, G.R. No. 204869. March 11, 2014

JURISDICTION

It is well settled that findings of fact of quasi-judicial agencies, such as the Commission of Audit, are

generally accorded respect and even finality by this Court, if supported by substantial evidence, in

recognition of their expertise on the specific matters under their jurisdiction. RUBEN REYNA AND

LLOYD SORIA v. COMMISSION ON AUDIT, G.R. No. 167219, February 8, 2011

Since the BSP, under its amended charter, continues to be a public corporation or a government

instrumentality, we come to the inevitable conclusion that it is subject to the exercise by the COA of

its audit jurisdiction in the manner consistent with the provisions of the BSP Charter. BOY SCOUTS

OF THE PHILIPPINES v. COMMSSION ON AUDIT, G.R. No. 177131, June 7, 2011

Under Commonwealth Act No. 327, as amended by Section 26 of Presidential Decree No. 1445, it is

the Commission on Audit which has primary jurisdiction over money claims against government

agencies and instrumentalities.

The scope of the COAs authority to take cognizance of claims is however circumscribed to mean

only liquidated claims, or those determined or readily determinable from vouchers, invoices, and

such other papers within reach of accounting officers. THE PROVINCE OF AKLAN v. JODY KING

CONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT CORP, G.R. Nos. 197592 & 20262, November 27, 2013

Under Section 2 (1) of Article IX-D of the Constitution, the COA was vested with the power,

authority, and duty to examine, audit, and settle the accounts of non-governmental entities

receiving subsidy or equity, directly or indirectly, from or through the government. Complementing

this power is Section 29 (1) of the Audit Code, which grants the COA visitorial authority over nongovernmental entities required to pay levy or government share.

The Manila Export and Cultural Office (MECO) is not a government-owned and controlled

corporation or a government instrumentality. It is a sui generis private entity especially entrusted

Page 20 of 100

Jurisprudence Political Law

by the government with the facilitation of unofficial relations with the people in Taiwan. However,

despite its non-governmental character, the MECO handles government funds in the form of the

verification fees it collects on behalf of the DOLE and the consular fees it collects under Section 2

(6) of E.O. 15, s. 2001. Hence, under existing laws, the accounts of the MECO pertaining to its

collection of such verification fees and consular fees should be audited by the Commission of

Audit. Section 14 (1), Book V of the Administrative Code authorizes the COA to audit accounts of

nongovernmental entities required to pay ... or have government share but only with respect to

funds ... coming from or through the government. This provision of law perfectly fits the MECO.

DENNIS A.B. FUNA v. MANILA ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL OFFICE AND COA, G.R. No. 193462,

February 4, 2014

The COA disallowed the payment of healthcare allowance of TESDA employees. COA is generally

accorded complete discretion in the exercise of its constitutional duty and responsibility to examine

and audit expenditures of public funds, particularly those which are perceptibly beyond what is

sanctioned by law. Only in instances when COA acts without or in excess of jurisdiction, or with

grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction shall the Court interfere.

TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (TESDA) v. THE

COMMISSION ON AUDIT, G.R. No. 196418, February 10, 2015

THE CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

JURISDICTION

Civil Service Commission (CSC) has jurisdiction over cases filed directly with it, regardless of who

initiated the complaint. CSC likewise exercises concurrent original jurisdiction with the Board of

Regents over administrative cases. CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION v. COURT OF APPEALS, et al.,

G.R. Nos. 176162, 178845, October 09, 2012

Where the law allows its Board of Directors to create its own staffing pattern, it may hire a person

even if the position being filled does not exist in the compensation and classification system of the

Civil Service Commission. The rules that the Civil Service Commission (CSC) formulates should

implement and be in harmony with the law it seeks to enforce. This is so since the CSC cannot

enforce civil service rules and regulations contrary to, and cannot override, the laws enacted by

Congress. TRADE AND INVESTMENT DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF THE PHILIPPINES v.

CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION, G.R. No. 182249, March 5, 2013

When a public school teacher is subject of an administrative action, concurrent jurisdiction exists in

the Civil Service Commission (CSC), the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Board of

Professional Teachers-Professional Regulatory Commission (PRC). Hence, the body that first takes

cognizance of the complaint shall exercise jurisdiction to the exclusion of the others. ALBERTO

PAT-OG, SR. v. CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION, G.R. No. 198755, June 5, 2013

ADDITIONAL, DOUBLE, OR INDIRECT COMPENSATION

There has been no change of any long-standing rule, thus, no redefinition of the term capital. The

terms capital stock subscribed or paid, capital stock, and capital were defined solely to

determine the basis for computing the supervision and regulation fees under Section 40 (e) and (f)

of the Public Service Act. HEIRS OF WILSON P. GAMBOA v. FINANCE SECRETARY MARGARITO B.

TEVES, G.R. No. 176579, October 09, 2012