Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aoki V Aoki Decision

Uploaded by

Matthew HamiltonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aoki V Aoki Decision

Uploaded by

Matthew HamiltonCopyright:

Available Formats

This opinion is uncorrected and subject to revision before

publication in the New York Reports.

----------------------------------------------------------------No. 28

In the Matter of Kevin Aoki, et

al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Echo Aoki, et al.,

Respondents.

--------------------------------Devon Aoki, et al.

Respondents,

Keiko Ono Aoki,

Appellant.

Seth B. Waxman, for appellant.

David C. Rose, for respondents.

Alex Long et al.; Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr., amici

curiae.

PIGOTT, J.:

This appeal involves a challenge to the validity of two

partial releases of testamentary powers of appointment executed

by the decedent Hiroaki (Rocky) Aoki, the founder of the Benihana

restaurant chain.

The Appellate Division's order declaring the

partial releases valid should be affirmed.

- 1 -

- 2 -

No. 28

I.

Rocky formed the Benihana Protective Trust (BPT) in

1998 to hold stock and other assets relating to Benihana.

In

creating the trust Rocky named his attorney, Darwin Dornbush, and

two of his children, Kevin and Kana, as trustees.1

The trust

instrument, which was prepared by attorney Norman Shaw, contained

a provision that granted Rocky an unlimited power "to appoint any

of the principal and accumulated net income remaining at his

death," with such power of appointment being "exercisable only by

a provision in [Rocky's] Will specifically referring to and

exercising the power."

In July 2002, Rocky married Keiko (Ono) Aoki.

Shortly

after the wedding, Kevin and Kana met with Dornbush to express

their concerns that Rocky had married Keiko without first having

Keiko execute a prenuptial agreement.

Dornbush arranged a

meeting with Kevin, Kana and Rocky the following day.

During

that meeting, it was agreed that a potential solution to the

problem was that Keiko execute a postnuptial agreement.

Efforts

to get Keiko to sign a postnuptial agreement, however, proved

fruitless.

When it became clear that Keiko would not execute

such an agreement, Shaw proposed that Rocky execute a partial

Another of Rocky's children, Kyle, was added as trustee

in 1999. In 2004, Dornbush resigned as trustee and was replaced

by attorney Kenneth Podziba. Thus, at the time this proceeding

was commenced, the trustees of the BPT were Kevin, Kana, Kyle and

Podziba.

- 2 -

- 3 -

No. 28

release of his power of appointment whereby Rocky could appoint

only his descendants at the time of his death.

On September 23, 2002, Kevin, Kana and Rocky met with

Dornbush.

Rocky reviewed a "final draft" of the partial release

(September Release), and Rocky executed the partial release the

following day.

As relevant here, the September Release provides

as follows:

"I hereby irrevocably partially release that

power of appointment so that, from now on, I

shall have only the following power:

"I shall have a testamentary power to appoint

any of the principal and accumulated net

income remaining at my death to or for the

benefit of any one or more of my descendants.

My right to select appointees from among my

descendants, to decide the share of the

appointive property that each appointee shall

receive, and to decide the terms (in trust or

otherwise) upon which each appointee shall

take the appointive property, shall be

unlimited in all respects. My power of

appointment shall be exercisable only by a

provision in my Will specifically referring

to and exercising the power" (emphases

supplied).

Three months later, due to changes in IRS regulations,

Rocky executed a second release (December Release) that further

irrevocably restricted his power to appoint by excluding any

descendants who were non-resident aliens.

In August 2003, Rocky retained attorney Joseph Manson

to draft a codicil to his Will.

The codicil, which made no

mention of the September or December Releases, appointed Keiko to

receive 25% of the trust assets upon Rocky's death, and income

- 3 -

- 4 -

No. 28

from the remaining 75% for the rest of her life.

It also

provided that upon Keiko's death, Keiko had the power to bequeath

the principal to one or more of Rocky's descendants in her Will.

At Manson's request, Shaw provided an opinion as to

whether Rocky's exercise of the power of appointment in the

codicil was valid.

Shaw's opinion was that the portion of the

codicil granting Keiko a beneficial interest in the trust was

invalid because the September Release rendered Keiko an

impermissible appointee of the trust.

Weeks later, Rocky

executed an affidavit stating that he did not realize that, by

executing the September and December Releases, he could no longer

leave his Benihana stock to Keiko or any other party, and, had he

known that that was the effect of the documents, he would not

have signed them.2

Four years later, in September 2007, Rocky executed a

new Last Will and Testament, whereby he attempted to exercise his

power of appointment consistent with the August 2003 codicil.

However, Rocky also hedged his bets, stating that if it was

determined that the exercise of his power of appointment in that

regard was "invalid because, contrary to my desires, the

The record is unclear as to why Rocky executed this

particular affidavit. It is not captioned and does not appear to

have been prepared for use in an action or proceeding.

Notwithstanding Rocky's contentions in this affidavit, however,

four years later, Rocky conceded at his deposition that Shaw had

explained to him the overall legal effect of the September

Release.

- 4 -

- 5 -

No. 28

[September and December Releases] . . . are found to be valid,"

then he exercised his power 50% in favor of his daughter, Devon,

and 50% in favor of his son, Steven.

Rocky died in July 2008, survived by Keiko and his six

children.

At no time prior to his death did Rocky attempt to

have either the September or December Releases declared invalid.

II.

The BPT trustees commenced this proceeding seeking a

determination as to the validity of the September and December

Releases.

Devon and Steven interposed an answer.

Keiko also

answered, asserting in one of her five affirmative defenses that

the Releases were invalid as "the product of fraud" or having

been "obtained through fraudulent devices."

At the conclusion of

discovery, Devon and Steven moved for summary judgment seeking an

order declaring the Releases valid and dismissing Keiko's

affirmative defenses.

Keiko opposed the motion, asserting that

there was a question of fact as to whether Rocky would have

signed the Releases had he known that in signing them he was

foreclosed from changing his mind in the future.

The Surrogate dismissed four of the affirmative

defenses, but allowed the fraud affirmative defense to remain.

As to that defense, the court held that there was a triable issue

of fact on the issue of constructive fraud, and whether the

proponents of the Releases (as opposed to Keiko) could meet their

burden of demonstrating that Rocky's signature on the Releases

- 5 -

- 6 -

No. 28

was voluntary and not the result of misrepresentation or omission

by attorneys Dornbush and Shaw.

The case proceeded to trial before the Surrogate, who

determined that a preponderance of the evidence established that

Rocky was not aware that the Releases were irrevocable, and that

Devon and Steven failed to meet their burden of establishing that

Rocky's execution of the Releases was voluntary and not the

result of the "misrepresentation, omission or concealment" by

Rocky's fiduciaries, Dornbush and Shaw.

The Surrogate therefore

decreed the September and December Releases invalid.

The Appellate Division unanimously reversed the

Surrogate's Court decree and declared the Releases valid (117

AD3d 499, 499 [1st Dept 2014]).

It ruled that the Surrogate

"erroneously shifted the burden of proof to Devon and Steven to

prove that the releases were not procured by fraud," pointing out

that neither Dornbush nor Shaw were parties to the Releases and

therefore could not benefit from them (see id. at 503 [emphasis

in original]).

The Appellate Division held that the record

demonstrated that Rocky understood that the Releases were

irrevocable (as evidenced by his deposition testimony), and that

Dornbush and Shaw never represented to Rocky that the Releases

were anything but irrevocable (see id.).

Nor was there any

indication that Dornbush or Shaw "either concealed from or did

not affirmatively provide Rocky with any information he needed to

make an informed decision" (id.).

And, it was of no moment that

- 6 -

- 7 -

No. 28

Rocky failed to ask any questions before signing the Releases,

because a party who signs a document without any valid excuse for

not having read it is bound by its terms (id.).

This Court granted Keiko leave to appeal, and we now

affirm.

III.

Keiko argues that the Surrogate properly applied the

constructive fraud doctrine in shifting the burden of proof to

Devon and Steven to establish that the Releases were not procured

by fraud.

According to Keiko, because Dornbush and Shaw, as

fiduciaries of Rocky, allegedly worked to further the interests

of other parties, the Appellate Division erred when it held that

the burden of proof was on Keiko to establish that the Releases

were procured by fraud.

We disagree.

It is a well-settled rule that "'fraud vitiates all

contracts, but as a general thing it is not presumed but must be

proved by the party seeking to [be] relieve[d] . . . from an

obligation on that ground'" (Matter of Gordon v Bialystoker Ctr.

& Bikur Cholim, Inc., 45 NY2d 692, 698 [1978], quoting Cowee v

Cornell, 75 NY 91, 99 [1878]).

However, an exception to that

general rule provides that where a fiduciary relationship exists

between the parties, the law of constructive fraud will operate

to shift the burden to the party seeking to uphold the

transaction to demonstrate the absence of fraud (see Matter of

Greiff, 92 NY2d 341, 345 [1998]).

In addressing the doctrine of

- 7 -

- 8 -

No. 28

constructive fraud, we have explained that when

"the relations between the contracting

parties appear to be of such a character as

to render it certain that they do not deal on

terms of equality but that either on the one

side from superior knowledge of the matter

derived from a fiduciary relation, or from

the overmastering influence, or on the other

from weakness, dependence, or trust

justifiably reposed, unfair advantage in a

transaction is rendered probable, there the

burden is shifted, the transaction is

presumed void, and it is incumbent on the

stronger party to show affirmatively that no

deception was practiced, no undue influence

was used, and that all was fair, open,

voluntary and well understood" (Cowee, 75 NY

at 99-100 [emphasis supplied]).

We have applied the constructive fraud doctrine in

different contexts, but in each one, the pertinent factor present

is that the fiduciary stood to benefit from the transaction

itself.

For example, in Matter of Gordon, we held that there was

a fiduciary relationship between an elderly nursing home resident

and the nursing home, such that the law of constructive fraud

applied and the burden of proof shifted to the nursing home to

demonstrate that the resident's large donation to the nursing

home was freely and voluntarily made (45 NY2d at 698-700).

In Fisher v Bishop, we set aside a mortgage executed by

an elderly farmer, which was executed on the advice of his

counsel (one Wattles) and for the satisfaction of the farmer's

creditors (108 NY 25, 27-28 [1888]).

In that case, the farmer's

son, with the assistance of Wattles (who had also done legal work

for the farmer), executed a deed and transfer of personal

- 8 -

- 9 -

No. 28

property by the son to the farmer to pay off debts that he owed

the farmer (see id. at 27).

The son thereafter absconded,

leaving the surety defendants -- Wattles and Bishop -- to pay off

the son's debt to a third party.3

Wattles and Bishop obtained

the bond and mortgage from the farmer after making repeated

threats that the underlying transfer from the son to the farmer

was fraudulent as against creditors (see id. at 27-28).

In

setting aside that transaction on the ground of undue influence,

we found that there was a fiduciary relationship between the

farmer and Wattles:

"The extent to which the [farmer] confided in

the defendant Wattles is clearly shown by the

fact that he had frequently employed him in

business transactions and that the

conveyances which he then threatened to annul

and overthrow were drawn by him, and accepted

under his advice and cooperation. It was a

gross breach of good faith for a person thus

trusted, and who had by conducting the

business, vouched for its validity and

lawfulness, to turn around for the purpose of

gaining a personal advantage, and assert that

he had been engaged in an illegal

transaction, which he could at his own option

annul and destroy" (id. at 29-30 [emphasis

supplied]).

Dornbush and Shaw were clearly Rocky's fiduciaries.

But that is only one part of the equation.

The critical inquiry

is whether they were either parties to the Releases or stood to

directly benefit from their execution, such that the burden

This particular fact is contained in the Appellate

Division decision (see Fisher v Bishop, 36 Hun 112, 113 [4th Dept

1885]).

- 9 -

- 10 -

No. 28

shifted to Devon and Steven to demonstrate that the Releases were

not procured by fraud.

Here, the only individuals who stood to benefit from

Rocky's execution of the Releases were his descendants.

Neither

Dornbush nor Shaw were parties to the Releases or stood to

directly benefit from their execution (cf. Matter of Gordon, 45

NY2d at 698-700; Fisher, 108 NY at 29-30).

If anything, the

execution of the Releases all but ensured that Dornbush and Shaw

would have no interest in, nor would receive any benefit from,

the trust assets.

Therefore, the Appellate Division correctly

determined that, because the fiduciary exception does not apply

in this case, the Surrogate had improperly shifted the burden of

proof to Devon and Steven to demonstrate that the Releases were

not procured by fraud.

In support of their motion for summary judgment, Devon

and Steven submitted copies of the Releases, which, on their

face, state that they are irrevocable and carefully set out their

legal effect, namely, that Rocky was limiting his power of

appointment to his descendants who were not non-resident aliens.

Devon and Steven also submitted the deposition testimony of Rocky

(taken in an unrelated action) whereby Rocky admitted that he

remembered signing the Releases.

Excerpts from the depositions

of Dornbush and Shaw, the latter testifying that he explained to

Rocky the significance of the Releases and what they were meant

to accomplish, were also submitted.

- 10 -

- 11 -

No. 28

In response, Keiko submitted, among other things, the

deposition transcript of Rocky whereby he conceded that Shaw had

explained to him the overall purpose of the September Release.

In light of this submission, it is undisputed that Shaw explained

the overall effect of the September Release to Rocky, and that

Rocky signed it.

As Keiko points out, Rocky testified that he

may have signed the Releases without actually reading them, but

that was not the result of any alleged misrepresentations or

omissions by Dornbush and/or Shaw, the latter having explained to

Rocky what he was signing and receiving confirmation from Rocky

that he wanted to sign the Releases.4

Absent any evidence of fraud, one who signs a document

is bound by its terms (see DaSilva v Musso, 53 NY2d 543, 550

[1981] [citations omitted]).

Because Keiko failed to raise a

triable issue of fact that the Releases were signed as a result

of fraud or other wrongful conduct, the Appellate Division

properly granted Devon and Steven summary judgment.

Accordingly,

the order of the Appellate Division should be affirmed, with

costs.

Keiko's contention that Dornbush and Shaw had formed an

attorney-client relationship with Kevin and Kana when the

Releases were signed, such that the attorneys were "effective

parties" to the Releases, is without merit. The record

establishes that Dornbush and Shaw executed the Releases at

Rocky's direction. Moreover, Keiko's assertion that Dornbush and

Shaw possessed an "interest" in the transaction because they

allegedly expected to receive profitable business from the

children in the future is mere speculation.

- 11 -

Matter of Aoki v Aoki

No. 28

STEIN, J.(dissenting):

While I generally agree with the majority's

articulation of the law of constructive fraud, I disagree with

its application of that law to the circumstances here.

In

determining whether Keiko Aoki's claim of constructive fraud was

properly supported, the majority frames the issue, in part, as

whether Darwin Dornbush and Norman Shaw (the attorneys) "were

parties to the Releases or stood to directly benefit from their

execution" (maj opn at 10).

Regarding that same element,

however, Keiko raised another possibility -- that the attorneys

acted as agents of two of Rocky Aoki's children, Kevin and Kana

Aoki (who, in turn, stood to benefit from the Releases), when the

attorneys allegedly breached their fiduciary duty to Rocky (see

generally Kirschner v KPMG LLP, 15 NY3d 446, 465, 468 [2010]

[acts of agents are imputed to their principals]).

In my view,

the existence of such an agency relationship would, if proven,

bring this case within the doctrine of constructive fraud.

Initially, we must be cognizant of the procedural

posture of this case and the burdens of proof attendant thereto.

While Surrogate's Court ultimately held a full bench trial after

denying Devon and Steven Aoki's motion for summary judgment, the

- 1 -

- 2 -

No. 28

Appellate Division's reversal of the order of Surrogate's Court

was limited to its determination of the summary judgment motion;

the Appellate Division did not reach the trial evidence or the

Surrogate's decision after trial.

necessarily so limited, as well.

Thus, our review is

Accordingly, the question

before this Court is whether, as the Appellate Division found,

Devon and Steven met their initial burden of establishing their

entitlement to judgment as a matter of law and, if so, whether

Keiko presented sufficient evidence to raise a triable question

of fact in opposition (see Vega v Restani Constr. Corp., 18 NY3d

499, 503 [2012]).

I agree with the majority's conclusion as to

the first part of that inquiry, but not the latter.

Pursuant to the law of constructive fraud, when a

fiduciary relationship exists between the parties, the burden

shifts from the party attempting to establish fraud to the party

seeking to uphold the transaction, who then must demonstrate the

absence of fraud (see Matter of Greiff, 92 NY2d 341, 345 [1998];

Matter of Paul, 105 AD2d 929, 929 [3d Dept 1984]).

There can be

no question in this case that the attorneys stood in a fiduciary

relationship to Rocky, and I concur with the majority's

conclusion that there is no proof that they were, themselves,

parties to the transaction or that they stood to gain,

personally, from the execution of the Releases.

However, in my

view, when we consider the evidence in a light most favorable to

Keiko, as we must because she is the nonmoving party (see Vega,

- 2 -

- 3 -

No. 28

18 NY3d at 503), a question of fact exists on the summary

judgment record as to the attorneys' possible agency relationship

with Rocky's children -- who did stand to gain from the Releases

-- such that the burden shifted to the children to establish the

absence of fraud.

Because that burden was not met, summary

judgment was inappropriate.

Keiko asserts that the attorneys drafted the Releases

based on the wishes of Kevin and Kana -- and thereby entered into

an attorney-client relationship with them -- rather than acting

at the insistence of, and in the sole best interests of, their

client Rocky.

Although Keiko argues that the attorneys suffered

from an impermissible conflict of interest if they represented

both Rocky and the children, for our purposes here we need not

make any such determination, as it is irrelevant whether an

actual attorney-client relationship was formed with the children.

That is, in the context of this summary judgment motion, even if

the relationship was not one of attorney and client, the evidence

was sufficient to create questions of fact as to whether the

attorneys drafted the Releases for the benefit of the children,

rather than for Rocky, and, if they were acting for the

children's benefit, whether they should be considered agents for

a party to the transaction and, thus, fall within the

constructive fraud doctrine.

In this regard, the record reflects several instances

of conflicting evidence with respect to the nature of the

- 3 -

- 4 -

No. 28

relationship between the attorneys and Rocky's children and,

ultimately, whether the Releases should be set aside as the

product of improper conduct by the attorneys.

For example,

Dornbush testified at his deposition that, after Keiko refused to

sign a postnuptial agreement, Kevin and Kana asked him and Shaw

if anything could be done to protect the business for the

children.

Dornbush admitted that he was receptive to their

concerns, although he was not sure if they sought legal advice,

business advice, or "parental" advice because they considered him

to be like an uncle.

Shaw testified that he performed some legal

work for Kevin and Kana as trustees, as well as for Kana,

individually.

According to Shaw's deposition testimony, the

attorneys' aim in generating possible solutions to Keiko's

refusal to sign a postnuptial agreement was to assuage concerns

being raised by the children, both directly and as transmitted

through Rocky, that Rocky's assets would be vulnerable to Keiko

after his death.

Shaw acknowledged that he formulated the idea

for the Releases, purportedly for the purpose of relieving family

strain caused by the lack of a prenuptial agreement, without

consulting with Rocky or anyone else other than Dornbush.

Shaw

further testified that he may have had a conversation with Kevin

about relieving this family strain.

In a September 13, 2002

outline for a meeting with Rocky, Shaw listed several options,

including a postnuptial agreement and releases, to insulate Rocky

- 4 -

- 5 -

No. 28

against pressure to appoint shares away from the children; it is

unclear who asked the attorneys for these options, or who

mentioned this supposed pressure on Rocky.

Shaw also testified

that he and Dornbush represented Rocky and the children, but that

the attorneys saw a potential conflict once Rocky's new lawyer

asked them to review the proposed codicil to Rocky's will for

validity.

When questioned about the September 2002 Release,

Dornbush testified that he did not have any notion as to whether

or not it was beneficial to Rocky; this raises a question as to

why he would have had his client sign such a document.

In

addition, Dornbush wrote in a memo that "fur will fly" when Rocky

and Keiko discovered the existence of the executed Releases,

suggesting that Dornbush believed that Rocky was unaware of the

Releases, or at least their meaning, even though he had signed

them.

As further evidence that the attorneys may not have

been acting on Rocky's behalf in the drafting and execution of

the Releases, Keiko points to the statement in Rocky's will that

it would be "contrary to [his] desires" for the Releases to be

found valid.

In addition, Rocky's affidavit stated that he did

not understand that, after he signed the Releases, he would be

unable to change his will to select his wife or any unrelated

person as a stock beneficiary, and that he never intended to

limit his ability to makes those choices.

While the majority

aptly notes the suspect nature of that affidavit -- and the same

- 5 -

- 6 -

No. 28

can arguably be said about some of the other evidence -- it is

beyond cavil that courts are not at liberty to make credibility

determinations or weigh evidence on a summary judgment motion

(see Vega, 18 NY3d at 505; Forrest v Jewish Guild for the Blind,

3 NY3d 295, 315 [2004]; Bliss v State of New York, 95 NY2d 911,

913 [2000]).

To be sure, nothing in the record provides

uncontroverted proof that the attorneys drafted, and arranged to

have Rocky execute, the Releases at the behest of the children,

only, and in the absence of a request by Rocky.

In fact, there

is some evidence to indicate that Rocky was present at all of the

meetings attended by Kevin and Kana, perhaps demonstrating that

the attorneys were not in an attorney-client or agency

relationship with the children, but met with them only in

furtherance of their professional and fiduciary obligations to

Rocky.

Nevertheless, all of the conflicting evidence, considered

together, is sufficient to create a triable question of fact

regarding whether the attorneys were acting on behalf of -- or as

agents of -- the children, and not Rocky, when they drafted the

Releases and supervised their execution (see McLenithan v

McLenithan, 273 AD2d 757, 758-759 [3d Dept 2000]; Matter of Paul,

105 AD2d at 930).

Accordingly, I would reverse the Appellate

Division order granting summary judgment to Devon and Steven

Aoki, and remit the case to that Court for a review of the

- 6 -

- 7 -

No. 28

Surrogate's decision after trial.1

*

Order affirmed, with costs. Opinion by Judge Pigott. Chief

Judge DiFiore and Judges Abdus-Salaam, Fahey and Garcia concur.

Judge Stein dissents in an opinion in which Judge Rivera concurs.

Decided March 31, 2016

In light of the Appellate Division's determination on the

summary judgment motion, that Court never addressed the trial

evidence or the Surrogate's decision after trial, although it had

been asked to do so. Thus, it would be appropriate for the

Appellate Division to conduct such a review based on the full

trial record.

- 7 -

You might also like

- Hicks v. Bank of America, N.A, 10th Cir. (2007)Document18 pagesHicks v. Bank of America, N.A, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 162. No. 163. Docket 30410. Docket 31157Document13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 162. No. 163. Docket 30410. Docket 31157Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- V. H. Carroll, Trustee in Bankruptcy of The Estate of Dayrold Eugene Davis v. National Live Stock Credit Corporation, in The Matter of Dayrold E. Davis, Bankrupt, 286 F.2d 362, 10th Cir. (1961)Document4 pagesV. H. Carroll, Trustee in Bankruptcy of The Estate of Dayrold Eugene Davis v. National Live Stock Credit Corporation, in The Matter of Dayrold E. Davis, Bankrupt, 286 F.2d 362, 10th Cir. (1961)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Watkins v. Mer, Arn, Per, Inc., 10th Cir. (1999)Document3 pagesWatkins v. Mer, Arn, Per, Inc., 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Alfred Brawer, 496 F.2d 703, 2d Cir. (1974)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Alfred Brawer, 496 F.2d 703, 2d Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES of America, Appellee, v. Max L. SHULMAN, AppellantDocument15 pagesUNITED STATES of America, Appellee, v. Max L. SHULMAN, AppellantScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- American Plastic Equipment, Inc. v. Cbs Inc., 886 F.2d 521, 2d Cir. (1989)Document11 pagesAmerican Plastic Equipment, Inc. v. Cbs Inc., 886 F.2d 521, 2d Cir. (1989)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- D C O A O T S O F: Cesar A. Vidal and Ruth VidalDocument5 pagesD C O A O T S O F: Cesar A. Vidal and Ruth VidalForeclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Usbank V Naifeh Ca Court of Appeal Favorable Tila Rescission Decision 07192016Document30 pagesUsbank V Naifeh Ca Court of Appeal Favorable Tila Rescission Decision 07192016api-310287335100% (1)

- MERS V JACOBYDocument22 pagesMERS V JACOBYDinSFLANo ratings yet

- Rock Island Plow Co. v. Reardon, 222 U.S. 354 (1912)Document5 pagesRock Island Plow Co. v. Reardon, 222 U.S. 354 (1912)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shawnee Lodging LLC. v. Underwriters at Lloyd's London, 10th Cir. (2009)Document4 pagesShawnee Lodging LLC. v. Underwriters at Lloyd's London, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- American Trust Co. v. New York Credit Men's Adjustment Bureau, Inc, 207 F.2d 685, 2d Cir. (1953)Document6 pagesAmerican Trust Co. v. New York Credit Men's Adjustment Bureau, Inc, 207 F.2d 685, 2d Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Superscope, Inc. v. Brookline Corp., Etc., Robert E. Lockwood, 715 F.2d 701, 1st Cir. (1983)Document3 pagesSuperscope, Inc. v. Brookline Corp., Etc., Robert E. Lockwood, 715 F.2d 701, 1st Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of Cohoes Industrial Terminal, Inc., Debtor. Leon C. Baker, Cross-Appellee v. Latham Sparrowbush Associates, Cross-Appellant, 931 F.2d 222, 2d Cir. (1991)Document12 pagesIn The Matter of Cohoes Industrial Terminal, Inc., Debtor. Leon C. Baker, Cross-Appellee v. Latham Sparrowbush Associates, Cross-Appellant, 931 F.2d 222, 2d Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Herbert R. Bennett, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Hawkeye Loan Company, Inc., and Hawkeye Credit Company v. First National Bank of Humboldt, Iowa, A Corporation, 443 F.2d 518, 1st Cir. (1971)Document5 pagesHerbert R. Bennett, Trustee in Bankruptcy of Hawkeye Loan Company, Inc., and Hawkeye Credit Company v. First National Bank of Humboldt, Iowa, A Corporation, 443 F.2d 518, 1st Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The United States of America v. Benjamin A. Schabert, 362 F.2d 369, 2d Cir. (1966)Document8 pagesThe United States of America v. Benjamin A. Schabert, 362 F.2d 369, 2d Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, First CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, First CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Latzko v. Equitable Trust Co., 275 U.S. 254 (1927)Document2 pagesLatzko v. Equitable Trust Co., 275 U.S. 254 (1927)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Spindle v. Shreve, 111 U.S. 542 (1884)Document6 pagesSpindle v. Shreve, 111 U.S. 542 (1884)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Misco Leasing, Inc., Formerly Intercontinental Leasing, Inc. v. L. L. Keller, 490 F.2d 545, 10th Cir. (1974)Document5 pagesMisco Leasing, Inc., Formerly Intercontinental Leasing, Inc. v. L. L. Keller, 490 F.2d 545, 10th Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Crowe v. Bolduc, 334 F.3d 124, 1st Cir. (2003)Document17 pagesCrowe v. Bolduc, 334 F.3d 124, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Olaco Vs CA Full TextDocument8 pagesOlaco Vs CA Full TextFai MeileNo ratings yet

- Independent School District No. 93, Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma v. Trinity Universal Insurance Company, 436 F.2d 622, 10th Cir. (1970)Document5 pagesIndependent School District No. 93, Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma v. Trinity Universal Insurance Company, 436 F.2d 622, 10th Cir. (1970)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Seventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lasker V OcwenDocument6 pagesLasker V OcwenBlaqRubiNo ratings yet

- Atkins v. N. & J. Dick & Co., 39 U.S. 114 (1840)Document9 pagesAtkins v. N. & J. Dick & Co., 39 U.S. 114 (1840)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Noonan v. Rauh, 119 F.3d 46, 1st Cir. (1997)Document13 pagesNoonan v. Rauh, 119 F.3d 46, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Klock, 210 F.2d 217, 2d Cir. (1954)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Klock, 210 F.2d 217, 2d Cir. (1954)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SubpoenaDocument4 pagesSubpoenaromeo n bartolomeNo ratings yet

- Marine Bank v. Kalt-Zimmers Co., 293 U.S. 357 (1934)Document6 pagesMarine Bank v. Kalt-Zimmers Co., 293 U.S. 357 (1934)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed 6/8/12 Partial Pub. Order 7/3/12 (See End of Opn.)Document19 pagesFiled 6/8/12 Partial Pub. Order 7/3/12 (See End of Opn.)Foreclosure FraudNo ratings yet

- Wafed 0Document12 pagesWafed 0washlawdailyNo ratings yet

- Byford v. United States, 185 F.2d 171, 10th Cir. (1950)Document5 pagesByford v. United States, 185 F.2d 171, 10th Cir. (1950)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- FiledDocument21 pagesFiledScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- OLACO V CO CHO CHIT G.R. No. L-58010Document8 pagesOLACO V CO CHO CHIT G.R. No. L-58010Mark John RamosNo ratings yet

- Russell v. Post, 138 U.S. 425 (1891)Document5 pagesRussell v. Post, 138 U.S. 425 (1891)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pete King v. United Benefit Fire Insurance Company, A Corporation, 377 F.2d 728, 10th Cir. (1967)Document8 pagesPete King v. United Benefit Fire Insurance Company, A Corporation, 377 F.2d 728, 10th Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Colonial American National Bank v. Robert L. Kosnoski, 617 F.2d 1025, 4th Cir. (1980)Document22 pagesColonial American National Bank v. Robert L. Kosnoski, 617 F.2d 1025, 4th Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Victor Leavitt v. United States, 393 F.2d 891, 1st Cir. (1968)Document4 pagesVictor Leavitt v. United States, 393 F.2d 891, 1st Cir. (1968)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- O'Laco vs. Co Cho ChitDocument16 pagesO'Laco vs. Co Cho ChitCourtney WorkmanNo ratings yet

- United States v. Crowe, 10th Cir. (2013)Document32 pagesUnited States v. Crowe, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Federal Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Kimsey, 203 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1953)Document3 pagesFederal Deposit Ins. Corp. v. Kimsey, 203 F.2d 446, 10th Cir. (1953)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Howard Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Company (A Delaware Corporation), 277 F.2d 46, 2d Cir. (1960)Document9 pagesHoward Farmer v. Arabian American Oil Company (A Delaware Corporation), 277 F.2d 46, 2d Cir. (1960)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- George Cohen Sons & Company, Ltd. v. Daniel Koch, 376 F.2d 629, 1st Cir. (1967)Document7 pagesGeorge Cohen Sons & Company, Ltd. v. Daniel Koch, 376 F.2d 629, 1st Cir. (1967)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Public Policy Bars Implied Trust RelationshipDocument4 pagesPublic Policy Bars Implied Trust RelationshipNyl20100% (1)

- Nacif V White-SorensonDocument46 pagesNacif V White-SorensonDinSFLANo ratings yet

- Trademark Properties v. A&E Television Networks, 4th Cir. (2011)Document51 pagesTrademark Properties v. A&E Television Networks, 4th Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sebree v. Dorr, 22 U.S. 558 (1824)Document5 pagesSebree v. Dorr, 22 U.S. 558 (1824)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Saccoccia, 433 F.3d 19, 1st Cir. (2005)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Saccoccia, 433 F.3d 19, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 135, Docket 89-5010Document6 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 135, Docket 89-5010Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wachovia Bank and Trust Company v. Charles E. Dameron, Iii, Trustee of The Estate of Cabana Club Apartments, Inc., in The Matter of Cabana Club Apartments, Inc., Debtor, 406 F.2d 803, 4th Cir. (1969)Document5 pagesWachovia Bank and Trust Company v. Charles E. Dameron, Iii, Trustee of The Estate of Cabana Club Apartments, Inc., in The Matter of Cabana Club Apartments, Inc., Debtor, 406 F.2d 803, 4th Cir. (1969)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Toledo Railways & Light Co. v. Hill, 244 U.S. 49 (1917)Document4 pagesToledo Railways & Light Co. v. Hill, 244 U.S. 49 (1917)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sammie A. Riggs v. British Commonwealth Corporation, A Texas Corporation, 459 F.2d 449, 10th Cir. (1972)Document3 pagesSammie A. Riggs v. British Commonwealth Corporation, A Texas Corporation, 459 F.2d 449, 10th Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- JKC Holding Company v. Washington Sports, 4th Cir. (2001)Document14 pagesJKC Holding Company v. Washington Sports, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Woodward v. Jewell, 140 U.S. 247 (1891)Document6 pagesWoodward v. Jewell, 140 U.S. 247 (1891)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Achille Bayart & Cie v. Crowe, 238 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (2001)Document9 pagesAchille Bayart & Cie v. Crowe, 238 F.3d 44, 1st Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Global Commerce Corporation, S. A. v. Clark-Babbitt Industries, Inc., 255 F.2d 105, 2d Cir. (1958)Document4 pagesGlobal Commerce Corporation, S. A. v. Clark-Babbitt Industries, Inc., 255 F.2d 105, 2d Cir. (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Joint Budget Schedule 2018 Release FINALDocument1 pageJoint Budget Schedule 2018 Release FINALMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- FY 18-19 Budget School Aid RunsDocument15 pagesFY 18-19 Budget School Aid RunsMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- 2018-19 Executive Budget Briefing BookDocument161 pages2018-19 Executive Budget Briefing BookMatthew Hamilton100% (1)

- State of The State BingoDocument5 pagesState of The State BingoMatthew Hamilton100% (1)

- New York State Plastic Bag Task Force ReportDocument88 pagesNew York State Plastic Bag Task Force ReportMatthew Hamilton100% (1)

- DiNapoli Debt Impact Study 2017Document30 pagesDiNapoli Debt Impact Study 2017Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- 2018 State of The State BookDocument374 pages2018 State of The State BookMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- SNY0118 Crosstabs011618Document7 pagesSNY0118 Crosstabs011618Nick ReismanNo ratings yet

- 6-21-17 Ethics Committee Letter To Heastie Re: McLaughlin InvestigationDocument3 pages6-21-17 Ethics Committee Letter To Heastie Re: McLaughlin InvestigationMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- SNY0118 Crosstabs011518Document3 pagesSNY0118 Crosstabs011518Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Approval #64-66 of 2017Document3 pagesApproval #64-66 of 2017Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- USA V Pigeon 100617Document29 pagesUSA V Pigeon 100617Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- 11-27-17 LetterDocument5 pages11-27-17 LetterNick ReismanNo ratings yet

- IDC Leader Jeff Klein Legal Memo Re: Sexual Harassment Allegation.Document3 pagesIDC Leader Jeff Klein Legal Memo Re: Sexual Harassment Allegation.liz_benjamin6490No ratings yet

- 6-22-17 Heastie Letter To Ethics Committee Re: McLaughlin InvestigationDocument1 page6-22-17 Heastie Letter To Ethics Committee Re: McLaughlin InvestigationMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

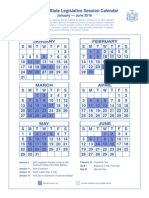

- 2016 Legislative Session CalendarDocument1 page2016 Legislative Session CalendarMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- 11-29-17 Heastie Letter To McLaughlin Re: McLaughlin InvestigationDocument2 pages11-29-17 Heastie Letter To McLaughlin Re: McLaughlin InvestigationMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Andrew Cuomo Letter To Jeff Bezos Re HQ2Document2 pagesAndrew Cuomo Letter To Jeff Bezos Re HQ2Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- DiNapoli Wall Street Profits Report 2017Document8 pagesDiNapoli Wall Street Profits Report 2017Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Comptroller's Fiscal Update: State Fiscal Year 2017-18 Receipts and Disbursements Through The Mid-YearDocument10 pagesComptroller's Fiscal Update: State Fiscal Year 2017-18 Receipts and Disbursements Through The Mid-YearMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Faso Scaffold Law BillDocument4 pagesFaso Scaffold Law BillMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- DiNapoli Federal Budget ReportDocument36 pagesDiNapoli Federal Budget ReportMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- OSC Municipal Water Systems ReportDocument14 pagesOSC Municipal Water Systems ReportMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- SNY1017 CrosstabsDocument6 pagesSNY1017 CrosstabsNick ReismanNo ratings yet

- Siena College October 2017 PollDocument8 pagesSiena College October 2017 PollMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- USA v. Skelos Appellate DecisionDocument12 pagesUSA v. Skelos Appellate DecisionMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Gov. Andrew Immigration Status Executive OrderDocument2 pagesGov. Andrew Immigration Status Executive OrderMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Gov. Andrew Cuomo Law Approval Message #6 - 2017Document1 pageGov. Andrew Cuomo Law Approval Message #6 - 2017Matthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Rockefeller Instittue 106 Ideas For A Constitutional ConventionDocument17 pagesRockefeller Instittue 106 Ideas For A Constitutional ConventionMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- NYS DFS Credit Reporting Agency RegulationsDocument6 pagesNYS DFS Credit Reporting Agency RegulationsMatthew HamiltonNo ratings yet

- 23rd India Conference of WAVES First AnnouncementDocument1 page23rd India Conference of WAVES First AnnouncementParan GoswamiNo ratings yet

- Sample Whistle Blower PolicyDocument2 pagesSample Whistle Blower Policy4geniecivilNo ratings yet

- Hvac BOQDocument10 pagesHvac BOQanwar2masNo ratings yet

- Welcome To All of You..: Nilima DasDocument16 pagesWelcome To All of You..: Nilima DasSteven GarciaNo ratings yet

- Courts CP, XO CP, Circumvention - DDI 2015 SWSDocument311 pagesCourts CP, XO CP, Circumvention - DDI 2015 SWSdavidsi325No ratings yet

- HI White Paper - Understanding The Effects of Selecting A Pump Performance Test Acceptance GradeDocument17 pagesHI White Paper - Understanding The Effects of Selecting A Pump Performance Test Acceptance Gradeashumishra007No ratings yet

- Economic Valuation of Cultural HeritageDocument331 pagesEconomic Valuation of Cultural Heritageaval_176466258No ratings yet

- TBDL 4Document3 pagesTBDL 4Dicimulacion, Angelica P.No ratings yet

- MKT202 - Group 6 - Marketing Research ProposalDocument9 pagesMKT202 - Group 6 - Marketing Research ProposalHaro PosaNo ratings yet

- Yamaha Tdm900 2002-2007 Workshop Service ManualDocument5 pagesYamaha Tdm900 2002-2007 Workshop Service ManualAlia Ep MejriNo ratings yet

- Harmonization and Standardization of The ASEAN Medical IndustryDocument75 pagesHarmonization and Standardization of The ASEAN Medical IndustryGanch AguasNo ratings yet

- Topic No-11 AIRCRAFT OXYGEN REQUIREMENTDocument9 pagesTopic No-11 AIRCRAFT OXYGEN REQUIREMENTSamarth SNo ratings yet

- Math 11 ABM Org - MGT Q2-Week 2Document16 pagesMath 11 ABM Org - MGT Q2-Week 2Gina Calling Danao100% (1)

- United International University: Post Graduate Diploma in Human Resource Management Course TitleDocument20 pagesUnited International University: Post Graduate Diploma in Human Resource Management Course TitleArpon Kumer DasNo ratings yet

- What is Reliability Centered Maintenance and its principlesDocument7 pagesWhat is Reliability Centered Maintenance and its principlesRoman AhmadNo ratings yet

- DB858DG90ESYDocument3 pagesDB858DG90ESYОлександр ЧугайNo ratings yet

- Transfer Price MechanismDocument5 pagesTransfer Price MechanismnikhilkumarraoNo ratings yet

- History of AviationDocument80 pagesHistory of AviationAmara AbrinaNo ratings yet

- Surface Additives GuideDocument61 pagesSurface Additives GuideThanh VuNo ratings yet

- Authority to abate nuisancesDocument2 pagesAuthority to abate nuisancesGR100% (1)

- Wells Fargo Combined Statement of AccountsDocument5 pagesWells Fargo Combined Statement of AccountsJaram Johnson100% (1)

- Entrepreneurship Starting and Operating A Small Business 4th Edition Mariotti Solutions Manual 1Document17 pagesEntrepreneurship Starting and Operating A Small Business 4th Edition Mariotti Solutions Manual 1willie100% (32)

- A European Call Option Gives A Person The Right ToDocument1 pageA European Call Option Gives A Person The Right ToAmit PandeyNo ratings yet

- Business Model Canvas CardsDocument10 pagesBusiness Model Canvas CardsAbhiram TalluriNo ratings yet

- For San Francisco To Become A CityDocument8 pagesFor San Francisco To Become A CityJun Mirakel Andoyo RomeroNo ratings yet

- Biosafety and Lab Waste GuideDocument4 pagesBiosafety and Lab Waste Guidebhramar bNo ratings yet

- Midas Method - Has One of The Simplest Goal Setting Processes I'Ve Ever Seen. It Just Works. I'Ve Achieved Things I Never Thought Were PossibleDocument0 pagesMidas Method - Has One of The Simplest Goal Setting Processes I'Ve Ever Seen. It Just Works. I'Ve Achieved Things I Never Thought Were PossiblePavel TisunovNo ratings yet

- Evacuation Process of HVAC SystemDocument23 pagesEvacuation Process of HVAC SystemDinesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Jess 303Document22 pagesJess 303Santanu Saha100% (1)

- SEZOnline SOFTEX Form XML Upload Interface V1 2Document19 pagesSEZOnline SOFTEX Form XML Upload Interface V1 2శ్రీనివాసకిరణ్కుమార్చతుర్వేదులNo ratings yet

- David and Goliath in the Modern Court: Extraordinary Trial Experiences of a Lawyer in the PhilippinesFrom EverandDavid and Goliath in the Modern Court: Extraordinary Trial Experiences of a Lawyer in the PhilippinesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Just Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionFrom EverandJust Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (175)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Win Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail--Every Place, Every TimeFrom EverandWin Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail--Every Place, Every TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (11)

- Government’s Achilles Heel or How to Win Any Court Case (we the people & common sense). Constitutional LegalitiesFrom EverandGovernment’s Achilles Heel or How to Win Any Court Case (we the people & common sense). Constitutional LegalitiesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The New Lawyer's Handbook: 101 Things They Don't Teach You in Law SchoolFrom EverandThe New Lawyer's Handbook: 101 Things They Don't Teach You in Law SchoolRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- The World's Funniest Lawyer Jokes: A Caseload of Jurisprudential JestFrom EverandThe World's Funniest Lawyer Jokes: A Caseload of Jurisprudential JestNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Addiction: A Biblical Path Towards FreedomFrom EverandOvercoming Addiction: A Biblical Path Towards FreedomRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Introduction to Internet Scams and Fraud: Credit Card Theft, Work-At-Home Scams and Lottery ScamsFrom EverandIntroduction to Internet Scams and Fraud: Credit Card Theft, Work-At-Home Scams and Lottery ScamsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Drafting Legal Notices in India: A Guide to Understanding the Importance of Legal Notices, along with DraftsFrom EverandDrafting Legal Notices in India: A Guide to Understanding the Importance of Legal Notices, along with DraftsRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- The Devil's Advocates: Greatest Closing Arguments in Criminal LawFrom EverandThe Devil's Advocates: Greatest Closing Arguments in Criminal LawRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo: Charles De Ville Wells, Gambler and Fraudster ExtraordinaireFrom EverandThe Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo: Charles De Ville Wells, Gambler and Fraudster ExtraordinaireNo ratings yet

- Drafting Applications Under CPC and CrPC: An Essential Guide for Young Lawyers and Law StudentsFrom EverandDrafting Applications Under CPC and CrPC: An Essential Guide for Young Lawyers and Law StudentsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Representing Yourself In Court (US): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnFrom EverandRepresenting Yourself In Court (US): How to Win Your Case on Your OwnRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Fast, the Fraudulent & the Fatal: The Dangerous and Dark Side of Illegal Street Racing, Drifting and Modified CarsFrom EverandThe Fast, the Fraudulent & the Fatal: The Dangerous and Dark Side of Illegal Street Racing, Drifting and Modified CarsNo ratings yet

- New Law Practice: A New Lawyer's Guide to Starting and Building a Law Practice, Economically!From EverandNew Law Practice: A New Lawyer's Guide to Starting and Building a Law Practice, Economically!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Stealing You Blind: Tricks of the Fraud TradeFrom EverandStealing You Blind: Tricks of the Fraud TradeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Drafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawFrom EverandDrafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Conducting Private Investigations: Private Investigator Entry Level (02E)From EverandIntroduction to Conducting Private Investigations: Private Investigator Entry Level (02E)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- So You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolFrom EverandSo You Want to be a Lawyer: The Ultimate Guide to Getting into and Succeeding in Law SchoolNo ratings yet

- Life After Law: Finding Work You Love with the J.D. You HaveFrom EverandLife After Law: Finding Work You Love with the J.D. You HaveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)