Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nursingresearchreport

Uploaded by

api-300699057Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nursingresearchreport

Uploaded by

api-300699057Copyright:

Available Formats

Running head: THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

The Effect of Diet and Statins on Hyperlipidemia

Sara Belcastro

Jason Hockey

Madalyn Lyons

Austin Mclean

Alex Mickler

Youngstown State University

April 13th, 2015

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

2

Abstract

The purpose of this literature review is to evaluate the effectiveness of the use of prescribed

lifestyle modifications (with particular focus on diet) and pharmacological agents (specifically

statins) on hyperlipidemia. Critical review of statin use and their efficacy in treating

hyperlipidemia is performed. Secondly, non-pharmacological lifestyle modifications are

examined and critiqued. Critique and evaluation of these treatment modalities is done by

examination and analysis of several peer reviewed studies. After this examination and analysis

was concluded, the findings suggest that a combination of lifestyle modifications and statin use

is the ideal treatment for decreasing low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) and increasing

high density lipoprotein cholesterol. The implication of this study is a further understanding for

the nursing community of the treatment modalities prescribed to patients with hyperlipidemia.

This extends to improved patient care, as well as allowing nurses to more effectively carry out

the roles of patient advocate and educator through the use of evidence based practice.

Introduction

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

3

In 2014, the Center for Disease Control published a report stating that heart disease was

the leading cause of death in America (CDC, 2015). Heart disease is a general term that refers to

changes in the heart resulting from blockages, narrowing of the arteries, angina, stroke,

alterations in the structures of the heart such as valve malfunctions and dysrhythmias. Managing

blood lipid levels is essential to the prevention of CVD and the morbidity and mortality related.

Recently, elevation of total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) has

received the most attention in prevention of cardiovascular risk. The modifiable factors like TC

and LDL-C can be managed by lifestyle changes and pharmacological therapies. Nurses must

consider the effectiveness of statins in lowering LDL-C levels in order to improve patients

quality and longevity of life. To further the understanding of the relationship between these

treatment modalities and patient outcomes, the question to be considered is as follow: How does

diet modifications and statin therapy affect cholesterol? Evaluation of literature will assist in

determining the effectiveness of dietary modifications and/or the use of statin therapy in reducing

lipid levels.

Review of Literature

Increased awareness of nutrition has brought about a change in treatment of

hyperlipidemia. Strong evidence has revealed that dietary choices influence factors on blood

pressure, glucose, and lipid levels. Hyperlipidemia, elevated blood lipid levels, may lead to

atherosclerosis, a contributing factor to heart disease. Thus, by reducing total cholesterol levels

to below 200 (the recommended value given by the American Heart Association)(AHA 2004),

risk for heart disease decreases. Concerning lipid level management, low density lipoprotein

cholesterol (LDL-C) is of particular importance. According to Dujrudee Chinwong, Jayanton

Patumanond, Surarong Chinwong, Khanchai Siriwattana, John Joseph Hall, and Arintaya

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

4

Phrommintikul, whose credentials range from members of Department of Pharmaceutical Care in

Thailand to the Center of Excellence in Applied Epidemiology, intensive LDL-C-lowering

therapy is needed soon after it is diagnosed in order to reduce the likelihood of complications

from coronary artery disease (2015).

Dietary saturated fatty acids (SFAs) are the dietary factor with the strongest impact

(elevation) on LDL-C. Trans-unsaturated fatty acids are less commonly found in foods but have

a similar effect on LDL-C (Catapano, Reiner 2011). Conversely, polyunsaturated fatty acids aid

in lowering LDL-C levels as well as lowering triglyceride (TC) levels. Omega-3 is a specific

type of polyunsaturated fatty acid found in oily fish. Wild salmon and mackerel are great sources

of Omega-3 fatty acids. As of now, there are currently no dietary guidelines for optimal omega-3

intake, however, the American Heart Association recommends eating fatty fish at least twice per

week. Limiting consumption of saturated fats and increasing consumption of fish and omega-3

fatty acids can reduce cholesterol levels. This is observed in a study titled The Nurses Health

Study which showed that women with higher consumption of fish and omega-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids had a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (Barrett 2013).One study has shown that a

combination of foods could reduce cholesterol as well as c-reactive protein levels similar to that

of a statin. An elevated c-reactive protein level increases a person's risk of cardiovascular

disease. The study completed by Jenkins, D. A., Kendall, C. C., Marchie, A., Faulkner, D. A.,

Josse, A. R., Wong, J. W., and Connelly, P. W.(2005), used participants that had previously

elevated LDL levels. The participants were randomized into three groups. The statin group was

on a very low-saturated-fat dairy and whole wheat cereal diet with a statin. The control group

was on a very low-saturated-fat dairy and whole wheat cereal diet without a statin. Lastly the

portfolio group was on a low-saturated-fat diet containing fibers, sterols, soy foods, and almonds.

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

5

All diets used were vegetarian. The statin used was 20mg lovastatin. Jenkins et al (2005) found

that the

c-reactive protein was reduced similarly on both statin, -16.3+/-6.7% (n=23, p=0.013) and

dietary portfolio, -23.8+/-6.9% (n=25, p=0.001) but not the control, 15.3+/-13.6% (n=28,

p=0.907). The application of this study is limited due to how many patients could and would be

compliant with a vegetarian diet (Jenkins, 2005).

Using dietary supplements may also be a strategy to improve plasma lipid levels. Dietary

supplements can be used either as an alternative to or in junction with lipid-lowering drugs.

Phytosterols are found naturally in vegetable oil and small amounts in almonds, chestnuts, grains

and legumes. The daily consumption of 2g of phytosterols can effectively lower TC and LDL-C

by 7-10% with little effect on HDL-C. Soy protein can be used instead of animal proteins that are

high in saturated fatty acids. Soy proteins are expected to lower LDL-C by 3-5% (Catapano &

Reiner, 2011). In addition to dietary modification, statin treatment must also be considered when

evaluating methods of cholesterol reduction.

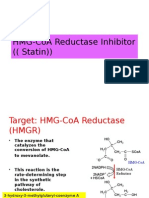

Statin use for treatment of hyperlipidemia has become quite common around the world,

and seems to be a first line treatment for many patients with hyperlipidemia.Statins primarily act

on reducing the synthesis of cholesterol in the liver by competitively inhibiting HMG-CoA

reductase. This would then cause a cascade effect lowering serum LDL-C levels (Catapano &

Reiner, 2011).With this increased use and dependence on statin therapy studies have begun to

flood in questioning their potency. In a meta analysis of 26 randomized trials of statins, 10%

reduction in all-cause mortality and 20% reduction in CAD death was recorded (Catapano,

Reiner 2011).This study also suggested that the capacity of statins to lower LDL-C depends

highly on the dosage and type of statin prescribed. Therefore, the prescribed statin should be

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

6

chosen based on the individual patients goal or desired TC or LDL-C levels.While this meta

analysis provides evidence that statins can be effective in mitigating potential complications of

hyperlipidemia, it does not specify that these reductions are because of an optimal TC or LDL-C

level.

In a particular study, conducted by Bojadzievski, Gabbay, Hollenbeak, and

Schaefer(2012), the use of statins and their effect on LDL-C control found that there is a

positive relationship between Statin and LDL-C control in the community setting. This

conclusion was reached by a retrospective observational study. In this study they used a total of

109 primary care providers and simply observed patients who had levels of LDLs less than 130

as well as less than 100 and the number of those patients on statins. The findings of this study

were that there was a linear association of patients with the intended levels of LDL and statin

use. What this means as the patients were prescribed statins the number of patients who were

within the goal parameters for LDL increased (Bojadzievski, Gabbay, Hollenbeak, & Schaefer,

2012).

Statins are not without flaw though. One study found that alone statin therapy did not

lower LDL-C to optimal levels.In this study conducted by Al-Khateeb, Al-Talib, Mohd, Yusof,

and Zilfalil (2013) there was a list of 980 dyslipidemic files collected for research data from, but

in the studies only patients who were on the standard statin dose and those receiving the statin or

other dosages after the index date of January 2007 were selected.The studys findings were as

stated by Al-Khateeb, 2013 There was a significant difference in the lipid profiles between the

dyslipidemic patients in this study and healthy populations from other studies for total

cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol and

triglyceride level, respectively. (Al-Khateeb, Al-Talib, Mohd, Yusof, Zilfalil, 272, 2013). This

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

7

statement explains that with just statin use, lipid levels of the subjects in the study were not near

the parameters of normal lipid levels in the healthy population. Further, regarding the use of

statins, a study conducted in Thailand based on their potency and effects on LDL-C will be

reviewed.

Dujrudee Chinwong and her colleagues performed a retrospective cohort study by

retrieving acute coronary syndrome patients information from the electronic database at Maharaj

Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital. Patients selected were diagnosed with either angina pectoris or

acute myocardial infarction. A total of 1,089 patients diagnosed with ACS were identified, but

only 396 remained in the final analysis due to missing data or baselines already below the target

range (<70mg/dL). With this exclusion, the group used for the study had an average younger age

(64.411.9 years versus 67.812.7 years, respectively, P<0.001). The remaining sample was then

categorized into two groups by statin potency (Chinwong et al., 2015).

In total, 396 patients were included in the study, with 229 (57.8%)

treated with high potency statins and 167 (42.2%) with low potency statins.

Patients using high potency statins had higher total cholesterol and LDL-C

levels at baseline, therefore they were believed to have an increased

severity of illness (Chinwong et al., 2015). Patients in the high potency statin

group were treated with simvastatin (40 mg), rosuvastatin (10 mg or 20 mg),

atorvastatin (20 mg or 40 mg), or pitavastatin (2 mg) daily, and were

expected to achieve an LDL-C reduction of 40% based on previous studies.

The low potency statin group included patients on simvastatin (10 mg or 20

mg) or pravastatin (40 mg) daily, and were expected LDL-C reduction of

<40%. According to Chinwong et al., the patient goal was to reach below 70

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

8

mg/dL (<1.8 mmol/L) during the follow-up period of 2 weeks to 1 year

(2015).

24.9% of the patients using high potency statins reached their target LDL-C, and 23.4%

of patients using low potency statin group reached their target. According to the authors, high

potency statins were not associated with increased LDL-C goal attainment (adjusted hazards

ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 0.791.88; P=0.363). Chinwong et al. (2015) stated,

"Patients using high potency statins were no more likely to reach their LDL-C target than

patients on low potency statins (hazards ratio 1.15, 95% confidence interval 0.761.73,

P=0.516), and the results remained the same after adjusting for propensity score (adjusted

hazards ratio 1.22, 95% confidence interval 0.791.88, P=0.363, Table 5)." (p. 127). Elements

pertaining the studys framework will be evaluated to establish its claims legitimacy.

This study was approved by the research ethics committee, Faculty of Medicine, and

Chiang Mai University in Thailand before commencement. The tertiary hospital used in the

analysis serves patients in Chiang Mai province, which has a population of 1,600,000, and

receives patients from 17 other provinces in northern Thailand. The selection of the population

involved those with either angina pectoris or mycardial infarction. These diagnoses confer with

Chinwongs reviewed literature sources, as valid candidates because coronary artery disease

usually occurs due to unstable angina, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction, or ST

segment elevation myocardial infarction. The researchers used a Cox proportional hazard model

to determine the relationship between statin potency and LDL-C goal attainment and a

propensity score adjustment to control for confounding by indication (Chinwong, et al., 2015).

Although there is substantial support for the studys credibility, other factors may have

contributed to the low success rate of statin therapy within the analysis.

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

9

One factor which may have attributed to the low target attainment rate was the LDL-C

goal (<70 mg/dL), based on the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology and the

European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS). This is a more difficult level to achieve than the

updated standard set by the National Cholesterol Education Program/Adult Treatment Panel III

(NCEP/ATP III) guideline (<200 mg/dL). However, more aggressive LDL-C targets are

recommended for ACS patients compared to healthy patients. (Chinwong, 2015). Also, the high

potency statins of this study, as they are defined, fall into the category of low to moderate

potency category used in the study by Rallidis et al. (Chinwong, 2015). These factors affect the

analysis itself, but other contributing factors may be more diversely generalized.

Approximately 25% of patients in this study (with LDL-C higher than 140 mg/dL at

baseline) would require combination therapy, including a statin to achieve their target LDL-C.

However, only seven patients (1.8%) were prescribed combination therapy, consistent with other

studies reviewed by Chinwong et al., reporting that statin combination therapy was used less

frequently in routine practice (2015). Due to potential adverse effects, including an increase in

muscle toxicity, cardiologists were possibly reluctant to titrate statin doses upwards, especially

since doubling the dose of a statin results in lowering LDL-C by only an additional 6%

(Chinwong et al., 2015). Simvastatin (40 mg), the most commonly used high potency statin, can

only result in about 43% LDL-C reduction and cannot decrease the LDL-C level to <70 mg/dL in

patients with a baseline level at <140 mg/dL, according to L. Osc, D. Budinski, N. Hounslow,

and V. Arneson. In this situation, atorvastatin, rosuvastatin or statin combination therapy should

be used to lower LDL-C to the target level (Chinwong et al., 2015, p. 130).

A positive relationship between statin potency and LDL-C goal attainment is well

established in some randomized controlled trials, while Chinwong et al. and other studies have

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

10

shown results which suggest that the potency of the statin used does not increase the likelihood

of reaching the recommended goal (2015). Combination therapy may be necessary to reach ideal

patient outcomes.

In conclusion, both statin use and diet modifications can be effective in lowering LDL-C.

This does not however mean that one is a replacement for the other. Patients may not be able to

rely on statin therapy alone because doctors are hesitant to increase dosages due to increased

risks with minute benefits, and also are not prescribed sufficiently with other pharmacologic

drugs. The research presented here shows that diet modifications alone may only offer a

moderate decrease in LDL-C and to bridge the gap between, statins provide an adequate

reduction in LDL-C. Recommended based on the reviewed literature, a combination of diet

modification and statin use is superior to either singular treatment modality.

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

11

References

Al-Khateeb, A., Al-Talib, H., Mohd, M., Yusof, Z., & Zilfalil, B. (2013). The Role of Lipid

Lowering Therapy in the Achievement of Therapuetic Goal among Malaysian

Hyperlipidemic Patients. Inernational Medical Journal, 20(3), 272-275. Retrieved April

1, 2015, from CINAHL.

American Heart Association. 2004. Building Healthier Lives Free of Cardiovascular Disease and

Stroke. Accessed April 6th 2015. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/

Barrett, S. (2013). The role of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in cardiovascular health.

Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine, 1926-30.

Bojadzievski, T., Schaefer, E., Hollenbeak, C. S., & Gabbay, R. A. (2012). Association between statin use

and lipid status in quality improvement initiatives: statin use, a potential surrogate?. Quality In

Primary Care, 20(6), 401-407

Catapano, A. L. , Reiner, Z (2011). ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias The Task

Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Athereosclerosis,

217 (1), 16-27.

Chinwong, D., Patumanond, J., Chinwong, S., Siriwattana, K., Gunaparn, S., Hall, J. J., &

Phrommintikul, A. (2015). Statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome: low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment and effect of statin potency. Therapeutics & Clinical Risk

Management, 11127-136. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S75608

Jenkins, D. A., Kendall, C. C., Marchie, A., Faulkner, D. A., Josse, A. R., Wong, J. W., &...

Connelly, P. W. (2005). Direct comparison of dietary portfolio vs statin on C-reactive

protein.European Journal Of Clinical Nutrition, 59(7), 851-860.

THE EFFECTS OF DIET AND STATINS ON HYPERLIPIDEMIA

12

doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602152

You might also like

- ENN PHARMACOLOGY BUNDLE PrintDocument142 pagesENN PHARMACOLOGY BUNDLE Printronique reid75% (4)

- Top-200-Drug ETSYDocument31 pagesTop-200-Drug ETSYBetsy Brown ByersmithNo ratings yet

- PSAP 2019 Dyslipidemia PDFDocument24 pagesPSAP 2019 Dyslipidemia PDFdellykets_323822919No ratings yet

- Treatment of Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument12 pagesTreatment of Chronic Kidney Diseaseaty100% (1)

- Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics-Lípidos 2009Document234 pagesEndocrinology and Metabolism Clinics-Lípidos 2009Tony Miguel Saba SabaNo ratings yet

- BIOS LIFE - Cleveland Clinic Trial by Dr. Dennis SprecherDocument5 pagesBIOS LIFE - Cleveland Clinic Trial by Dr. Dennis SprecherHisWellnessNo ratings yet

- Treating Dyslipidemia: Lifestyle and DrugsDocument16 pagesTreating Dyslipidemia: Lifestyle and DrugsangelmedurNo ratings yet

- AAO McqsDocument199 pagesAAO Mcqssafasayed50% (2)

- Living Longer and Healthier LifeDocument233 pagesLiving Longer and Healthier Lifeweisberger100% (1)

- Nursing Research PresentaionDocument33 pagesNursing Research Presentaionapi-300699057No ratings yet

- j3 2010Document12 pagesj3 2010Taha FransNo ratings yet

- Ezetimibe - A Novel Add On Treatment Strategy To Achieve Targeted LDL in Patients With Uncontrolled LDL Levels On High Dose Statin AloneDocument9 pagesEzetimibe - A Novel Add On Treatment Strategy To Achieve Targeted LDL in Patients With Uncontrolled LDL Levels On High Dose Statin AloneEditor ERWEJNo ratings yet

- Metabolic SyndromeDocument7 pagesMetabolic SyndromeDannop GonzálezNo ratings yet

- DyslipidemiaManagement Continuum 2011Document13 pagesDyslipidemiaManagement Continuum 2011Zuleika DöObsönNo ratings yet

- Clinical research shows rosuvastatin more effective than atorvastatin for metabolic syndromeDocument9 pagesClinical research shows rosuvastatin more effective than atorvastatin for metabolic syndromeSohail AhmedNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Use of Statins For Dyslipidemia in The Pediatric PopulationDocument13 pagesReview Article: Use of Statins For Dyslipidemia in The Pediatric PopulationkemalmiaNo ratings yet

- Human Nutrition and MetabolismDocument7 pagesHuman Nutrition and MetabolismMisyani MisyaniNo ratings yet

- Effects of Diet and Simvastatin On Serum Lipids, Insulin, and Antioxidants in Hypercholesterolemic MenDocument8 pagesEffects of Diet and Simvastatin On Serum Lipids, Insulin, and Antioxidants in Hypercholesterolemic MenAranel BomNo ratings yet

- Clinical Trial 2016Document11 pagesClinical Trial 2016guugle gogleNo ratings yet

- AnnotationsDocument3 pagesAnnotationsAegina FestinNo ratings yet

- Eggs and Beyond: Is Dietary Cholesterol No Longer Important?Document2 pagesEggs and Beyond: Is Dietary Cholesterol No Longer Important?Dianne Faye ManabatNo ratings yet

- Managing Hypertriglyceridemia in Diabetic PatientsDocument5 pagesManaging Hypertriglyceridemia in Diabetic Patientsjimrod1950No ratings yet

- Diretrizes de Prática Clínica para o Tratamento de HipertrigliceriemiaDocument24 pagesDiretrizes de Prática Clínica para o Tratamento de Hipertrigliceriemiaqmatheusq wsantoswNo ratings yet

- Polygenic Hypercholesterolemia: Causes, Risks & TreatmentDocument6 pagesPolygenic Hypercholesterolemia: Causes, Risks & TreatmentSamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- Atp IiiDocument6 pagesAtp IiiLuis Ángel RuizNo ratings yet

- CLC 4960230910Document7 pagesCLC 4960230910walnut21No ratings yet

- Effects of Garlic On Dyslipidemia in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument5 pagesEffects of Garlic On Dyslipidemia in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusMuhammad Iqbal AriefNo ratings yet

- Mty1107 Sec9 Saquiton MF LipidsfornursingDocument8 pagesMty1107 Sec9 Saquiton MF LipidsfornursingCes SaquitonNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Long-Term Dietary Therapy On Patients With HypertriglyceridemiaDocument11 pagesThe Effects of Long-Term Dietary Therapy On Patients With Hypertriglyceridemiaraul zea calcinaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Metabolic Syndrome-Role of Dietary Fat TypeDocument7 pages2 - Metabolic Syndrome-Role of Dietary Fat TypeJuliana ZapataNo ratings yet

- Nej MP 1112023Document2 pagesNej MP 1112023Marcella DharmawanNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument93 pagesResearch Articlearyan batangNo ratings yet

- Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (Article) Author United States Department of Veterans AffairsDocument9 pagesType 2 Diabetes Mellitus (Article) Author United States Department of Veterans Affairsnaljnaby9No ratings yet

- Reduction of Plasma Triglycerides by Diet in Subjects With Chronic Renal FailureDocument15 pagesReduction of Plasma Triglycerides by Diet in Subjects With Chronic Renal FailureDina sayunaNo ratings yet

- Significance of Orlistat for Dyslipidemia, SBP, and BMIDocument7 pagesSignificance of Orlistat for Dyslipidemia, SBP, and BMIGestne AureNo ratings yet

- ANNALS DyslipidemiaDocument16 pagesANNALS Dyslipidemiaewb100% (1)

- AntioksidanDocument5 pagesAntioksidanRakasiwi GalihNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2017)Document12 pagesOriginal Article: Journal of Clinical Lipidology (2017)IrhamNo ratings yet

- Beneficial Effects of Viscous Dietary Fiber From Konjac-Mannan in Subjects With The Insulin Resistance Syndro M eDocument6 pagesBeneficial Effects of Viscous Dietary Fiber From Konjac-Mannan in Subjects With The Insulin Resistance Syndro M eNaresh MaliNo ratings yet

- Objective:: BackgroundDocument23 pagesObjective:: BackgroundJanine DimaangayNo ratings yet

- Insulin and IncretinsDocument6 pagesInsulin and IncretinspykkoNo ratings yet

- English JournalDocument4 pagesEnglish JournalRamya HarlistyaNo ratings yet

- BMC Family PracticeDocument19 pagesBMC Family PracticeFirda AndiNo ratings yet

- Atp 3 Upd 04Document13 pagesAtp 3 Upd 04api-3696252No ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia 2018Document8 pagesDyslipidemia 2018R JannahNo ratings yet

- 632 Management of Nonalcoholic SteatohepatitisDocument15 pages632 Management of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitispedrogarcia7No ratings yet

- Low Carb StudyDocument15 pagesLow Carb StudycphommalNo ratings yet

- Dietary Fiber DMDocument8 pagesDietary Fiber DMAnnisa SavitriNo ratings yet

- Low-Dose Rosuvastatin Improves Lipids in Type 2 DiabetesDocument11 pagesLow-Dose Rosuvastatin Improves Lipids in Type 2 DiabetesZahid MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Moderate CarbohydrateDocument9 pagesModerate CarbohydrateAndrea TorrealdayNo ratings yet

- Management DislipidemiaDocument5 pagesManagement DislipidemiakemalmiaNo ratings yet

- Terapia Farmacologica Dell'obesità, 2008Document11 pagesTerapia Farmacologica Dell'obesità, 2008todino32No ratings yet

- Management of HyperlipidemiaDocument34 pagesManagement of HyperlipidemiaCarleta StanNo ratings yet

- Paper Title: (16 Bold)Document9 pagesPaper Title: (16 Bold)vegeto portmanNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Inositol Ate in Diabetic DyslipidemiaDocument10 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Inositol Ate in Diabetic DyslipidemiavanigvNo ratings yet

- Dyson LineDocument10 pagesDyson LineSharly DwijayantiNo ratings yet

- He Ssion 2009Document15 pagesHe Ssion 2009raisa putriNo ratings yet

- Heart Diseases: An Overview On Clinical Trials: Dr. Khaled Dhifullah Al-Harby Consultant Family PhysicianDocument68 pagesHeart Diseases: An Overview On Clinical Trials: Dr. Khaled Dhifullah Al-Harby Consultant Family PhysicianalghaidanyNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study Regarding The Effect of NDocument7 pagesClinical Study Regarding The Effect of NcolceardoinaNo ratings yet

- Non Pharmacological Treatment of HypertensionDocument5 pagesNon Pharmacological Treatment of HypertensionyolandadwiooNo ratings yet

- Research: Cite This As: BMJ 2010 341:c3337Document7 pagesResearch: Cite This As: BMJ 2010 341:c3337Deepak DahiyaNo ratings yet

- Example 6Document4 pagesExample 6Tutor BlairNo ratings yet

- Glycemic index, glycemic load, and blood pressure meta-analysisDocument15 pagesGlycemic index, glycemic load, and blood pressure meta-analysisLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Srikant H 2016Document10 pagesSrikant H 2016aditya sekarNo ratings yet

- Devaraj2006 PDFDocument7 pagesDevaraj2006 PDFMuhammad Pandji PurnamaNo ratings yet

- PotentialdevelopmentjournalDocument2 pagesPotentialdevelopmentjournalapi-300699057No ratings yet

- Clinical Nursing JudgmentDocument6 pagesClinical Nursing Judgmentapi-300699057No ratings yet

- Resume 1Document1 pageResume 1api-300699057No ratings yet

- Depression Case Study By: Alex Mickler YSU Mental Health Nursing ClinicalDocument8 pagesDepression Case Study By: Alex Mickler YSU Mental Health Nursing Clinicalapi-300699057No ratings yet

- Sperlings Bestplaces Warren ReligionDocument1 pageSperlings Bestplaces Warren Religionapi-300699057No ratings yet

- Sperlings Bestplaces Warren EconomyDocument2 pagesSperlings Bestplaces Warren Economyapi-300699057No ratings yet

- Strengthening The Global Risk ManagementDocument31 pagesStrengthening The Global Risk ManagementSriNoviantiNo ratings yet

- SOAP Note - Peter The DeanDocument5 pagesSOAP Note - Peter The DeanWu TracyNo ratings yet

- Government of Canada Report On Pricing of Crestor (Rosuvastatin)Document2 pagesGovernment of Canada Report On Pricing of Crestor (Rosuvastatin)jennabushNo ratings yet

- Stroke in Surgical PatientsDocument13 pagesStroke in Surgical Patientscarlos gordilloNo ratings yet

- Building Your Peripheral Artery Disease Toolkit MDocument11 pagesBuilding Your Peripheral Artery Disease Toolkit MehaffejeeNo ratings yet

- MIMS Doctor August 2015 RGDocument48 pagesMIMS Doctor August 2015 RGDika MidbrainNo ratings yet

- Cholesterol Lowering Drugs Work in Many Different WaysDocument2 pagesCholesterol Lowering Drugs Work in Many Different WaysSassySeanNo ratings yet

- Focus Forward Style Guide-ALL DOCSDocument46 pagesFocus Forward Style Guide-ALL DOCSShahin AfridiNo ratings yet

- pcsk9 and Cholesterol Management1Document43 pagespcsk9 and Cholesterol Management1api-586798131No ratings yet

- Dyslipidemia Update by DR SarmaDocument96 pagesDyslipidemia Update by DR SarmaDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- LED Light Therapy Consultation Form 1Document4 pagesLED Light Therapy Consultation Form 1infotandhmedicalNo ratings yet

- Lovastatin - ClinicalKeyDocument49 pagesLovastatin - ClinicalKeyMaría Fernanda SánchezNo ratings yet

- Cha2ds2 Vasc ScoreDocument12 pagesCha2ds2 Vasc ScorehelviaseptariniNo ratings yet

- HMG-CoA Reductase InhibitorDocument10 pagesHMG-CoA Reductase InhibitorGilang Sumiarsih PramanikNo ratings yet

- Crowdcast Q&A Master Question ListDocument65 pagesCrowdcast Q&A Master Question ListArnon CavaeiroNo ratings yet

- Pitavastatin (Livalo®) : National Drug Monograph January 2012Document18 pagesPitavastatin (Livalo®) : National Drug Monograph January 2012anishNo ratings yet

- FAandDZ PDFDocument8 pagesFAandDZ PDFCosmin GabrielNo ratings yet

- Drug ToxicityDocument12 pagesDrug ToxicityLaeeq R MalikNo ratings yet

- HPLC Methods For The Determination of Simvastatin and AtorvastatinDocument16 pagesHPLC Methods For The Determination of Simvastatin and AtorvastatinFaizNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Outcomes of PCSK9 InhibitorsDocument17 pagesCardiovascular Outcomes of PCSK9 InhibitorsAndi SusiloNo ratings yet

- مجلة توفيقTJMSDocument89 pagesمجلة توفيقTJMSTaghreed Hashim al-NoorNo ratings yet

- Antihyperlipidemic Drugs: Mechanisms and ManagementDocument30 pagesAntihyperlipidemic Drugs: Mechanisms and ManagementSaifNo ratings yet

- Penatalaksanaan HiperkolesterolemiaDocument24 pagesPenatalaksanaan HiperkolesterolemiaQarina Hasyala PutriNo ratings yet

- Research in Public Health by Prof DR Rwamakuba ZephanieDocument120 pagesResearch in Public Health by Prof DR Rwamakuba ZephanieDr Zephanie RwamakubaNo ratings yet