Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consti Law Review Digest 1

Uploaded by

marydalemCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consti Law Review Digest 1

Uploaded by

marydalemCopyright:

Available Formats

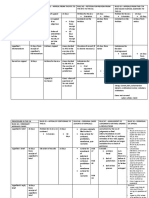

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

1. PEOPLE V.

PERFECTO

2. MACARIOLA V.

ASUNCION

3. MANILA PRINCE

HOTEL V. GSIS

4. CHAVEZ V.

JUDICIAL & BAR

COUNCIL

5. PERFECTO V.

MEER

6. ENDENCIA V.

DAVID

7. NITAFAN V. CIR

8. REPUBLIC V. SB

9. AQUINO, JR. V.

ENRILE

10.

JAVELLANA

V. EXEC.

SECRETARY

11.

OCCENA V.

COMELEC

12.

PHIL. BAR

ASSOC. V.

COMELEC

13.

LAWYERS

LEAGUE FOR A

BETTER

PHILIPPINES V.

AQUINO

14.

IN RE:

BERMUDEZ

15.

IN RE:

LETTER OF

ASSOCIATE

JUSTICE PUNO OF

THE CA

16.

DE LEON V.

ESGUERRA

17.

GONZALES

V. COMELEC

18.

DEFENSORSANTIAGO V.

COMELEC

19.

LAMBINO V.

COMELEC

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

1.PEOPLE V PERFECTO

G.R. No. L-18463, October 4, 1922

FACTS:

The issue started when the Secretary of the Philippine Senate, Fernando Guerrero,

discovered that the documents regarding the testimony of the witnesses in an

investigation of oil companies had disappeared from his office. Then, the day

following the convening of Senate, the newspaper La Nacion edited by herein

respondent Gregorio Perfecto published an article against the Philippine Senate.

Here, Mr. Perfecto was alleged to have violated Article 256 of the Spanish Penal

Code provision that punishes those who insults the Ministers of the Crown. Hence,

the issue.

ISSUE: Whether or not Article 256 of the Spanish Penal Code (SPC) is still in force

and can be applied in the case at bar?

HELD: No.

REASONING: The Court stated that during the Spanish Government, Article 256 of

the SPC was enacted to protect Spanish officials as representatives of the King.

However, the Court explains that in the present case, we no longer have Kings nor

its representatives for the provision to protect. Also, with the change of sovereignty

over the Philippines from Spanish to American, it means that the invoked provision

of the SPC had been automatically abrogated. The Court determined Article 256 of

the SPC to be political in nature for it is about the relation of the State to its

inhabitants, thus, the Court emphasized that it is a general principle of the public

law that on acquisition of territory, the previous political relations of the ceded

region are totally abrogated.Hence, Article 256 of the SPC is considered no longer

in force and cannot be applied to the present case. Therefore, respondent was

acquitted.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

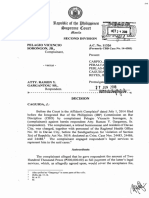

2. MACARIOLA V ASUNCION

114 SCRA 77, May 31, 1982

Facts:

When the decision in Civil Case No. 3010 rendered by respondent Hon. Judge Elias

B. Asuncion of Court of First Instance of Leyte became final on June 8, 1863 for lack

of an appeal, a project of partition was submitted to him which he later approved in

an Order dated October 23, 1963. Among the parties thereto was complainant

Bernardita R. Macariola.

One of the properties mentioned in the project of partition was Lot 1184. This lot

according to the decision rendered by Judge Asuncion was adjudicated to the

plaintiffs Reyes in equal shares subdividing Lot 1184 into five lots denominated as

Lot 1184-A to 1184-E.

On July 31, 1964 Lot 1184-E was sold to Dr. Arcadio Galapon who later sold a portion

of Lot 1184-E to Judge Asuncion and his wife Victoria Asuncion. Thereafter spouses

Asuncion and spouses Galapon conveyed their respective shares and interests in Lot

1184-E to the Traders Manufacturing and Fishing Industries Inc. wherein Judge

Asuncion was the president.

Macariola then filed an instant complaint on August 9, 1968 docketed as Civil Case

No. 4234 in the CFI of Leyte against Judge Asuncion with "acts unbecoming a judge"

alleging that Judge Asuncion in acquiring by purchase a portion of Lot 1184-E

violated Article 1491 par. 5 of the New Civil Code, Art. 14, pars. 1 and 5 of the Code

of Commerce, Sec. 3 par. H of R.A. 3019, Sec. 12 Rule XVIII of the Civil Service Rules

and Canon 25 of the Canons of Judicial Ethics.

On November 2, 1970, Judge Jose Nepomuceno of the CFI of Leyte rendered a

decision dismissing the complaints against Judge Asuncion.

After the investigation, report and recommendation conducted by Justice Cecilia

Munoz Palma of the Court of Appeals, she recommended on her decision dated

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

March 27, 1971 that Judge Asuncion be exonerated.

Issue:

Does Judge Asuncion, now Associate Justice of Court of Appeals violated any law in

acquiring by purchase a parcel of Lot 1184-E which he previously decided in a Civil

Case No. 3010 and his engagement in business by joining a private corporation

during his incumbency as a judge of the CFI of Leyte constitute an "act unbecoming

of a judge"?

Ruling: No. The respondent Judge Asuncion's actuation does not constitute of an

"act unbecoming of a judge." But he is reminded to be more discreet in his private

and business activities.

SC ruled that the prohibition in Article 1491 par. 5 of the New Civil Code applies only

to operate, the sale or assignment of the property during the pendency of the

litigation involving the property. Respondent judge purchased a portion of Lot 1184E on March 6, 1965, the in Civil Case No. 3010 which he rendered on June 8, 1963

was already final because none of the parties therein filed an appeal within the

reglementary period. Hence, the lot in question was no longer subject to litigation.

Furthermore, Judge Asuncion did not buy the lot in question directly from the

plaintiffs in Civil Case No. 3010 but from Dr. Arcadio Galapon who earlier purchased

Lot1184-E from the plaintiffs Reyes after the finality of the decision in Civil Case No.

3010.

SC stated that upon the transfer of sovereignty from Spain to the US and later on

from the US to the Republic of the Philippines, Article 14 of Code of Commerce must

be deemed to have been abrogated because where there is change of sovereignty,

the political laws of the former sovereign, whether compatible or not with those of

the new sovereign, are automatically abrogated, unless they are expressly reenacted by affirmative act of the new sovereign. There appears no enabling or

affirmative act that continued the effectivity of the aforestated provision of the Code

of Commerce, consequently, Art. 14 of the Code of Commerce has no legal and

binding effect and cannot apply to the respondent Judge Asuncion.

Respondent Judge cannot also be held liable to par. H, Section 3 of R.A. 3019

because the business of the corporation in which respondent participated had

obviously no relation or connection with his judicial office.

SC stated that respondent judge and his wife deserve the commendation for their

immediate withdrawal from the firm 22 days after its incorporation realizing that

their interest contravenes the Canon 25 of the Canons of Judicial Ethics.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

3.MANILA PRINCE HOTEL V GSIS

G.R. No. 122156, February 3, 1997

I.THE FACTS

Pursuant to the privatization program of the Philippine Government, the GSIS

sold in public auction its stake in Manila Hotel Corporation (MHC). Only 2 bidders

participated: petitioner Manila Prince Hotel Corporation, a Filipino corporation, which

offered to buy 51% of the MHC or 15,300,000 shares atP41.58 per share, and

Renong Berhad, a Malaysian firm, with ITT-Sheraton as its hotel operator, which bid

for the same number of shares atP44.00 per share, orP2.42 more than the bid of

petitioner.

Petitioner filed a petition before the Supreme Court to compel the GSIS to

allow it to match the bid of Renong Berhad. It invoked the Filipino First

Policyenshrined in 10, paragraph 2, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution,which

provides that in the grant of rights, privileges, and concessions covering the

national economy and patrimony, the State shall give preference to qualified

Filipinos.

II.THE ISSUES

1.Whether 10, paragraph 2, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution is a selfexecuting provision and does not need implementing legislation to carry it

into effect;

2.Assuming 10, paragraph 2, Article XII is self-executing, whether the

controlling shares of the Manila Hotel Corporation form part of our

patrimony as a nation;

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

3.Whether GSIS is included in the term State, hence, mandated to

implement 10, paragraph 2, Article XII of the Constitution; and

4.Assuming GSIS is part of the State, whether it should give preference to the

petitioner, a Filipino corporation, over Renong Berhad, a foreign

corporation, in the sale of the controlling shares of the Manila Hotel

Corporation.

III.THE RULING

[The Court, voting 11-4, DISMISSED the petition.]

1.YES, 10, paragraph 2, Article XII of the 1987 Constitution is a selfexecuting provision and does not need implementing legislation to carry it

into effect.

Sec. 10, second par., of Art XII is couched in such a way as not to make it

appear that it is non-self-executing but simply for purposes of style. But, certainly,

the legislature is not precluded from enacting further laws to enforce the

constitutional provision so long as the contemplated statute squares with the

Constitution. Minor details may be left to the legislature without impairing the selfexecuting nature of constitutional provisions.

Respondents . . . argue that the non-self-executing nature of Sec. 10, second

par., of Art. XII is implied from the tenor of the first and third paragraphs of the

same section which undoubtedly are not self-executing. The argument is flawed. If

the first and third paragraphs are not self-executing because Congress is still to

enact measures to encourage the formation and operation of enterprises fully

owned by Filipinos, as in the first paragraph, and the State still needs legislation to

regulate and exercise authority over foreign investments within its national

jurisdiction, as in the third paragraph, thena fortiori, by the same logic, the second

paragraph can only be self-executing as it does not by its language require any

legislation in order to give preference to qualified Filipinos in the grant of rights,

privileges and concessions covering the national economy and patrimony. A

constitutional provision may be self-executing in one part and non-self-executing in

another.

xxx. Sec. 10, second par., Art. XII of the 1987 Constitution is a mandatory,

positive command which is complete in itself and which needs no further guidelines

or implementing laws or rules for its enforcement. From its very words the provision

does not require any legislation to put it in operation. It isper sejudicially

enforceable.When our Constitution mandates that[i]n the grant of rights, privileges,

and concessions covering national economy and patrimony, the State shall give

preference to qualified Filipinos,it means just that - qualified Filipinos shall be

preferred. And when our Constitution declares that a right exists in certain specified

circumstances an action may be maintained to enforce such right notwithstanding

the absence of any legislation on the subject; consequently, if there is no statute

especially enacted to enforce such constitutional right, such right enforces itself by

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

its own inherent potency and puissance, and from which all legislations must take

their bearings. Where there is a right there is a remedy. Ubi jus ibi remedium.

2.YES, the controlling shares of the Manila Hotel Corporation form

part of our patrimony as a nation.

In its plain and ordinary meaning, the termpatrimonypertains to

heritage.When the Constitution speaks ofnational patrimony,it refers not only to the

natural resources of the Philippines, as the Constitution could have very well used

the termnatural resources, but also to thecultural heritageof the Filipinos.

For more than eight (8) decades Manila Hotel has bore mute witness to the

triumphs and failures, loves and frustrations of the Filipinos; its existence is

impressed with public interest; its own historicity associated with our struggle for

sovereignty, independence and nationhood. Verily, Manila Hotel has become part of

our national economy and patrimony. For sure, 51% of the equity of the MHC comes

within the purview of the constitutional shelter for it comprises the majority and

controlling stock, so that anyone who acquires or owns the 51% will have actual

control and management of the hotel. In this instance, 51% of the MHC cannot be

disassociated from the hotel and the land on which the hotel edifice stands.

Consequently, we cannot sustain respondents claim that theFilipino First

Policyprovision is not applicablesince what is being sold is only 51% of the

outstanding shares of the corporation, not the Hotel building nor the land upon

which the building stands.

3.YES, GSIS is included in the term State, hence, it is mandated to

implement 10, paragraph 2, Article XII of the Constitution.

It is undisputed that the sale of 51% of the MHC could only be carried out

with the prior approval of the State acting through respondent Committee on

Privatization. [T]his fact alone makes the sale of the assets of respondents GSIS and

MHC a state action.In constitutional jurisprudence, the acts of persons distinct

from the government are considered state action covered by the Constitution (1)

when the activity it engages in is a public function; (2) when the government is so

significantly involved with the private actor as to make the government responsible

for his action; and, (3) when the government has approved or authorized the action.

It is evident that the act of respondent GSIS in selling 51% of its share in respondent

MHC comes under the second and third categories of state action. Without doubt

therefore the transaction, although entered into by respondent GSIS, is in fact a

transaction of the State and therefore subject to the constitutional command.

When the Constitution addresses the State it refers not only to the people but

also to the government as elements of the State. After all, government is composed

of three (3) divisions of power - legislative, executive and judicial. Accordingly, a

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

constitutional mandate directed to the State is correspondingly directed to the three

(3) branches of government. It is undeniable that in this case the subject

constitutional injunction is addressed among others to the Executive Department

and respondent GSIS, a government instrumentality deriving its authority from the

State.

4.YES, GSISshould give preference to the petitioner in the sale of

the controlling shares of the Manila Hotel Corporation.

It should be stressed that while the Malaysian firm offered the higher bid it is

not yet the winning bidder. The bidding rules expressly provide that the highest

bidder shall only be declared the winning bidder after it has negotiated and

executed the necessary contracts, and secured the requisite approvals. Since

theFilipino First Policyprovision of the Constitution bestows preference onqualified

Filipinosthe mere tending of the highest bid is not an assurance that the highest

bidder will be declared the winning bidder. Resultantly, respondents are not bound

to make the award yet, nor are they under obligation to enter into one with the

highest bidder. For in choosing the awardee respondents are mandated to abide by

the dictates of the 1987 Constitution the provisions of which are presumed to be

known to all the bidders and other interested parties.

Paragraph V. J. 1 of the bidding rules provides that[i]f for any reasonthe

Highest Bidder cannot be awarded the Block of Shares, GSIS may offer this to other

Qualified Bidders that have validly submitted bids provided that these Qualified

Bidders are willing to match the highest bid in terms of price per share. Certainly,

the constitutional mandate itself isreason enoughnot to award the block of shares

immediately to the foreign bidder notwithstanding its submission of a higher, or

even the highest, bid. In fact, we cannot conceive of astrongerreasonthan the

constitutional injunction itself.

In the instant case, where a foreign firm submits the highest bid in a public

bidding concerning the grant of rights, privileges and concessions covering the

national economy and patrimony, thereby exceeding the bid of a Filipino, there is no

question that the Filipino will have to be allowed to match the bid of the foreign

entity. And if the Filipino matches the bid of a foreign firm the award should go to

the Filipino. It must be so if we are to give life and meaning to theFilipino First

Policyprovision of the 1987 Constitution. For, while this may neither be expressly

stated nor contemplated in the bidding rules, the constitutional fiat is omnipresent

to be simply disregarded. To ignore it would be to sanction a perilous skirting of the

basic law.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

4.CHAVEZ V JBC

G.R. No. 202242 July 17, 2012

Facts:

The case is in relation to the process of selecting the nominees for the

vacant seat of Supreme Court Chief Justice following Renato Coronas

departure.

Originally, the members of the Constitutional Commission saw the need to create a

separate, competent and independent body to recommend nominees to the

President. Thus, it conceived of a body representative of all the stakeholders in the

judicial appointment process and called it the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC).

In particular, Paragraph 1 Section 8, Article VIII of the Constitution states that (1) A

Judicial and Bar Council is hereby created under the supervision of the Supreme

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

Court composed of the Chief Justice as ex officio Chairman, the Secretary of Justice,

and a representative of the Congress as ex officio Members, a representative of the

Integrated Bar, a professor of law, a retired Member of the Supreme Court, and a

representative of the private sector. In compliance therewith, Congress, from the

moment of the creation of the JBC, designated one representative from the

Congress to sit in the JBC to act as one of the ex officio members.

In 1994 however, the composition of the JBC was substantially altered. Instead of

having only seven (7) members, an eighth (8th) member was added to the JBC as

two (2) representatives from Congress began sitting in the JBC one from the House

of Representatives and one from the Senate, with each having one-half (1/2) of a

vote. During the existence of the case, Senator Francis Joseph G. Escudero and

Congressman Niel C. Tupas, Jr. (respondents) simultaneously sat in JBC as

representatives of the legislature.It is this practice that petitioner has questioned in

this petition.

The respondents claimed that when the JBC was established, the framers originally

envisioned a unicameral legislative body, thereby allocating a representative of the

National Assembly to the JBC. The phrase, however, was not modified to aptly jive

with the change to bicameralism which was adopted by the Constitutional

Commission on July 21, 1986. The respondents also contend that if the

Commissioners were made aware of the consequence of having a bicameral

legislature instead of a unicameral one, they would have made the corresponding

adjustment in the representation of Congress in the JBC; that if only one house of

Congress gets to be a member of JBC would deprive the other house of

representation, defeating the principle of balance.

The respondents further argue that the allowance of two (2) representatives of

Congress to be members of the JBC does not render JBCs purpose of providing

balance nugatory; that the presence of two (2) members from Congress will most

likely provide balance as against the other six (6) members who are undeniably

presidential appointees. Supreme Court held that it has the power of review the

case herein as it is an object of concern, not just for a nominee to a judicial post, but

for all the citizens who have the right to seek judicial intervention for rectification of

legal blunders.

Issue:

Whether the practice of the JBC to perform its functions with eight (8)

members, two (2) of whom are members of Congress, defeats the letter

and spirit of the 1987 Constitution.

Held:

No. The current practice of JBC in admitting two members of the Congress to

perform the functions of the JBC is violative of the 1987 Constitution. As such, it is

unconstitutional.

One of the primary and basic rules in statutory construction is that where the words

of a statute are clear, plain, and free from ambiguity, it must be given its literal

meaning and applied without attempted interpretation. It is a well-settled principle

of constitutional construction that the language employed in the Constitution must

be given their ordinary meaning except where technical terms are employed.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

As such, it can be clearly and unambiguously discerned from Paragraph 1, Section

8, Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution that in the phrase, a representative of

Congress, the use of the singular letter a preceding representative of Congress

is unequivocal and leaves no room for any other construction. It is indicative of what

the members of the Constitutional Commission had in mind, that is, Congress may

designate only one (1) representative to the JBC. Had it been the intention that

more than one (1) representative from the legislature would sit in the JBC, the

Framers could have, in no uncertain terms, so provided.

Moreover, under the maxim noscitur a sociis, where a particular word or phrase is

ambiguous in itself or is equally susceptible of various meanings, its correct

construction may be made clear and specific by considering the company of words

in which it is founded or with which it is associated. Every meaning to be given to

each word or phrase must be ascertained from the context of the body of the

statute since a word or phrase in a statute is always used in association with other

words or phrases and its meaning may be modified or restricted by the latter.

Applying the foregoing principle to this case, it becomes apparent that the word

Congress used in Article VIII, Section 8(1) of the Constitution is used in its generic

sense. No particular allusion whatsoever is made on whether the Senate or the

House of Representatives is being referred to, but that, in either case, only a

singular representative may be allowed to sit in the JBC

Considering that the language of the subject constitutional provision is plain and

unambiguous, there is no need to resort extrinsic aids such as records of the

Constitutional Commission. Nevertheless, even if the Court should proceed to look

into the minds of the members of the Constitutional Commission, it is undeniable

from the records thereof that it was intended that the JBC be composed of seven (7)

members only. The underlying reason leads the Court to conclude that a single vote

may not be divided into half (1/2), between two representatives of Congress, or

among any of the sitting members of the JBC for that matter.

With the respondents contention that each representative should be admitted from

the Congress and House of Representatives, the Supreme Court, after the perusal of

the records of Constitutional Commission, held that Congress, in the context of

JBC representation, should be considered as one body. While it is true that there are

still differences between the two houses and that an inter-play between the two

houses is necessary in the realization of the legislative powers conferred to them by

the Constitution, the same cannot be applied in the case of JBC representation

because no liaison between the two houses exists in the workings of the JBC. No

mechanism is required between the Senate and the House of Representatives in the

screening and nomination of judicial officers. Hence, the term Congress must be

taken to mean the entire legislative department.

The framers of Constitution, in creating JBC, hoped that the private sector and the

three branches of government would have an active role and equal voice in the

selection of the members of the Judiciary. Therefore, to allow the Legislature to have

more quantitative influence in the JBC by having more than one voice speak,

whether with one full vote or one-half (1/2) a vote each, would negate the principle

of equality among the three branches of government which is enshrined in the

Constitution.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

It is clear, therefore, that the Constitution mandates that the JBC be composed of

seven (7) members only. Thus, any inclusion of another member, whether with one

whole vote or half (1/2) of it, goes against that mandate. Section 8(1), Article VIII of

the Constitution, providing Congress with an equal voice with other members of the

JBC in recommending appointees to the Judiciary is explicit. Any circumvention of

the constitutional mandate should not be countenanced for the Constitution is the

supreme law of the land. The Constitution is the basic and paramount law to which

all other laws must conform and to which all persons, including the highest officials

of the land, must defer. Constitutional doctrines must remain steadfast no matter

what may be the tides of time. It cannot be simply made to sway and accommodate

the call of situations and much more tailor itself to the whims and caprices of the

government and the people who run it.

Notwithstanding its finding of unconstitutionality in the current composition of the

JBC, all its prior official actions are nonetheless valid. In the interest of fair play

under the doctrine of operative facts, actions previous to the declaration of

unconstitutionality are legally recognized. They are not nullified.

WHEREFORE, the petition is GRANTED. The current numerical composition of the

Judicial and Bar Council IS declared UNCONSTITUTIONAL. The Judicial and Bar

Council is hereby enjoined to reconstitute itself so that only one ( 1) member of

Congress will sit as a representative in its proceedings, in accordance with Section

8( 1 ), Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution. This disposition is immediately

executory.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

5.PERFECTO V MEER

Facts:

In April, 1947 the Collector of Internal Revenue required Mr. Justice Gregorio

Perfecto to pay income tax upon his salary as member of this Court during the year

1946. After paying the amount (P802), he instituted this action in the Manila Court

of First Instance contending that the assessment was illegal, his salary not being

taxable for the reason that imposition of taxes thereon would reduce it in violation

of the Constitution.

Issue:

Does the imposition of an income tax upon this salary amount to a diminution

thereof?

Held:

Yes. Wherefore, unless and until our Legislature approves an amendment to the

Income Tax Law expressly taxing "that salaries of judges thereafter appointed", the

O'Malley case is not relevant. As in the United States during the second period, we

must hold that salaries of judges are not included in the word "income" taxed by the

Income Tax Law. Two paramount circumstances may additionally be indicated, to

wit:

First, when the Income Tax Law was first applied to the Philippines 1913, taxable

"income" did not include salaries of judicial officers when these are protected from

diminution. That was the prevailing official belief in the United States, which must

be deemed to have been transplanted here ; and second, when the Philippine

Constitutional Convention approved (in 1935) the prohibition against diminution of

the judges' compensation, the Federal principle was known that income tax on

judicial salaries really impairs them.

Our Constitution provides in its Article VIII, section 9, that the members of the

Supreme Court and all judges of inferior courts "shall receive such compensation as

may be fixed by law, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in

office." It also provides that "until Congress shall provide otherwise, the Chief Justice

of the Supreme Court shall receive an annual compensation of sixteen thousand

pesos". When in 1945 Mr. Justice Perfecto assumed office, Congress had not

"provided otherwise", by fixing a different salary for associate justices. He received

salary at the rate provided by the Constitution, i.e., fifteen thousand pesos a year.

This is not proclaiming a general tax immunity for men on the bench. These pay

taxes. Upon buying gasoline, or cars or other commodities, they pay the

corresponding duties. Owning real property, they pay taxes thereon. And on

incomes other than their judicial salary, assessments are levied. It is only when the

tax is charged directly on their salary and the effect of the tax is to diminish their

official stipend that the taxation must be resisted as an infringement of the

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

fundamental charter.

Judges would indeed be hapless guardians of the Constitution if they did not

perceive and block encroachments upon their prerogatives in whatever form. The

undiminishable character of judicial salaries is not a mere privilege of judges

personal and therefore waivable but a basic limitation upon legislative or

executive action imposed in the public interest (Evans vs. Gore).

With what purpose does the Constitution provide that the compensation of the

judges "shall not be diminished during their continuance in office"? Is it primarily to

benefit the judges, or rather to promote the public weal by giving them that

independence which makes for an impartial and courageous discharge of the

judicial function? Does the provision merely forbid direct diminution, such as

expressly reducing the compensation from a greater to a less sum per year, and

thereby leave the way open for indirect, yet effective, diminution, such as

withholding or calling back a part as tax on the whole? Or does it mean that the

judge shall have a sure and continuing right to the compensation, whereon he

confidently may rely for his support during his continuance in office, so that he need

have no apprehension lest his situation in this regard may be changed to his

disadvantage?

The Constitution was framed on the fundamental theory that a larger measure of

liberty and justice would be assured by vesting the three powers the legislative,

the executive, and the judicial in separate departments, each relatively

independent of the others and it was recognized that without this independence

if it was not made both real and enduring the separation would fail of its purpose.

all agreed that restraints and checks must be imposed to secure the requisite

measure of independence; for otherwise the legislative department, inherently the

strongest, might encroach on or even come to dominate the others, and the judicial,

naturally the weakest, might be dwarf or swayed by the other two, especially by the

legislative.

These considerations make it very plain, as we think, that the primary purpose of

the prohibition against diminution was not to benefit the judges, but, like the clause

in respect of tenure, to attract good and competent men to the bench, and to

promote that independence of action and judgment which is essential to the

maintenance of the guaranties, limitations, and pervading principles of the

constitution, and to the admiration of justice without respect to persons, and with

equal concern for the poor and the rich.

Carefully analyzing the three cases (Evans, Miles and O'Malley) and piecing them

together, the logical conclusion may be reached that although Congress may validly

declare by law that salaries of judges appointed thereafter shall be taxed as income

(O'Malley vs. Woodrough) it may not tax the salaries of those judges already in

office at the time of such declaration because such taxation would diminish their

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

salaries (Evans vs. Gore; Miles vs. Graham). In this manner the rationalizing

principle that will harmonize the allegedly discordant decision may be condensed.

In the recent case of Evans vs. Gore the Supreme Court of the United States decided

that by taxing the salary of a federal judge as a part of his income, Congress was in

effect reducing his salary and thus violating Art. III, sec. 1, of the Constitution.

Anyhow the O'Malley case declares no more than that Congress may validly enact a

law taxing the salaries of judges appointed after its passage. Here in the Philippines

no such law has been approved. The O'Malley ruling does not cover the situation in

which judges already in office are made to pay tax by executive interpretation,

without express legislative declaration.

It is hard to see, appellants asserts, how the imposition of the income tax may

imperil the independence of the judicial department. The danger may be

demonstrated. Suppose there is power to tax the salary of judges, and the judiciary

incurs the displeasure of the Legislature and the Executive. In retaliation the income

tax law is amended so as to levy a 30 per cent on all salaries of government officials

on the level of judges. This naturally reduces the salary of the judges by 30 per

cent, but they may not grumble because the tax is general on all receiving the

same amount of earning, and affects the Executive and the Legislative branches in

equal measure. However, means are provided thereafter in other laws, for the

increase of salaries of the Executive and the Legislative branches, or their

perquisites such as allowances, per diems, quarters, etc. that actually compensate

for the 30 per cent reduction on their salaries. Result: Judges compensation is

thereby diminished during their incumbency thanks to the income tax law.

Consequence: Judges must "toe the line" or else. Second consequence: Some few

judges might falter; the great majority will not. But knowing the frailty of human

nature, and this chink in the judicial armor, will the parties losing their cases against

the Executive or the Congress believe that the judicature has not yielded to their

pressure?

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

6. ENDENCIA V DAVID

93 Phil. 699 Political Law The Judiciary Te Legislature Separation of Powers

Statutory Construction Who May Interpret Laws

Saturnino David, the then Collector of Internal Revenue, ordered the taxing of

Justice Pastor Endencias and Justice Fernando Jugos (and other judges) salary

pursuant to Sec. 13 of Republic Act No. 590 which provides that

No salary wherever received by any public officer of the Republic of the

Philippines shall be considered as exempt from the income tax,

payment of which is hereby declared not to be a diminution of his

compensation fixed by the Constitution or by law.

The judges however argued that under the case of Perfecto vs Meer, judges are

exempt from taxation this is also in observance of the doctrine of separation of

powers, i.e., the executive, to which the Internal Revenue reports, is separate from

the judiciary; that under the Constitution, the judiciary is independent and the

salaries of judges may not be diminished by the other branches of government; that

taxing their salaries is already a diminution of their benefits/salaries (see Section 9,

Art. VIII, Constitution).

The Solicitor General, arguing in behalf of the CIR, states that the decision in

Perfecto vs Meer was rendered ineffective when Congress enacted Republic Act No.

590.

ISSUE: Whether or not Sec 13 of RA 590 is constitutional.

HELD: No. The said provision is a violation of the separation of powers. Only courts

have the power to interpret laws. Congress makes laws but courts interpret them. In

Sec. 13, R.A. 590, Congress is already encroaching upon the functions of the courts

when it inserted the phrase: payment of which [tax] is hereby declared not to be a

diminution of his compensation fixed by the Constitution or by law.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

Here, Congress is already saying that imposing taxes upon judges is not a

diminution of their salary. This is a clear example of interpretation or ascertainment

of the meaning of the phrase which shall not be diminished during their

continuance in office, found in Section 9, Article VIII of the Constitution, referring to

the salaries of judicial officers. This act of interpreting the Constitution or any part

thereof by the Legislature is an invasion of the well-defined and established

province and jurisdiction of the Judiciary.

The rule is recognized elsewhere that the legislature cannot pass any declaratory

act, or act declaratory of what the law was before its passage, so as to give it any

binding weight with the courts. A legislative definition of a word as used in a statute

is not conclusive of its meaning as used elsewhere; otherwise, the legislature would

be usurping a judicial function in defining a term.

The interpretation and application of the Constitution and of statutes is within the

exclusive province and jurisdiction of the judicial department, and that in enacting a

law, the Legislature may not legally provide therein that it be interpreted in such a

way that it may not violate a Constitutional prohibition, thereby tying the hands of

the courts in their task of later interpreting said statute, especially when the

interpretation sought and provided in said statute runs counter to a previous

interpretation already given in a case by the highest court of the land.

7. NITAFAN V CIR

152 SCRA 284 Political Law Constitutional Law The Judicial Department

Judicial Autonomy Income Tax Payment By The Judiciary

Judge David Nitafan and several other judges of the Manila Regional Trial Court seek

to prohibit the Commissioner of Internal Revenue (CIR) from making any deduction

of withholding taxes from their salaries or compensation for such would tantamount

to a diminution of their salary, which is unconstitutional. Earlier however, or on June

7, 1987, the Court en banc had already reaffirmed the directive of the Chief Justice

which directs the continued withholding of taxes of the justices and the judges of

the judiciary but the SC decided to rule on this case nonetheless to settle the issue

once and for all.

ISSUE: Whether or not the members of the judiciary are exempt from the payment

of income tax.

HELD: No. The clear intent of the framers of the Constitution, based on their

deliberations, was NOT to exempt justices and judges from general taxation.

Members of the judiciary, just like members of the other branches of the

government, are subject to income taxation. What is provided for by the

constitution is that salaries of judges may not be decreased during their

continuance in office. They have a fix salary which may not be subject to the whims

and caprices of congress. But the salaries of the judges shall be subject to the

general income tax as well as other members of the judiciary.

But may the salaries of the members of the judiciary be increased?

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

Yes. The Congress may pass a law increasing the salary of the members of the

judiciary and such increase will immediately take effect thus the incumbent

members of the judiciary (at the time of the passing of the law increasing their

salary) shall benefit immediately.

Congress can also pass a law decreasing the salary of the members of the judiciary

but such will only be applicable to members of the judiciary which were appointed

AFTER the effectivity of such law.

Note: This case abandoned the ruling in Perfecto vs Meer and in Endencia vs David.

8. REPUBLIC V SB

GR NO. 104768, 2003, SEPARATE OPINION PUNO J.

Bill of Rights

Effect of the 1986 February Revolution on the 1973 Constitution.

The 1986 February Revolution was done in defiance of the provisions of the 1973

Constitution. The resulting government was indisputably a revolutionary

government bound by no constitution or legal limitations except treaty obligations

that the revolutionary government, as the de jure government, assumed under

international law. The Bill of Rights under the 1973 Constitution was inoperative

during that period, as it was abrogated by the Revolutionary government. But since

the Philippines is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights and the Human Declaration of Human Rights, the protection accorded to

individuals under the same remained in effect even without the 1973 Constitution.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

(Republic vs. SB, Maj. Gen. Josephus Ramas, et al., G.R. No. 104768, July 21, 2003).

The 1973 Constitution was abrogated by the Revolutionary government;

During the interregnum (from the time of the Revolutionary government up to

February 2, 1987), the directives and orders of the revolutionary government were

the supreme law because no constitution limited the extent and scope of such

directives and orders. With the abrogation of the 1973 Constitution by the

successful resolution, there was no municipal law higher than the directives and

orders of the revolutionary government. Thus, during the interregnum, a person

could not invoke any exclusionary right under a Bill of Rights because there was

neither a constitution nor a Bill of Rights during that interregnum. (Republic vs. SB,

et

al.,

supra.)

Effect of the operation of the Bill of Rights under the 1973 Constitution remained

operative even during the Revolutionary government.

It rendered void all sequestration orders issued by the PCGG before the adoption of

the Freedom Constitution. The sequestration orders, which direct the freezing and

even the take-over of private property by mere executive issuance without judicial

action, would violate the due process and search and seizure clauses of the Bill of

Rights. During the interregnum the government in power was concededly a

revolutionary government bound by no constitution. No one could validly question

the sequestration orders as violative of the Bill of Rights because there was no Bill

of Rights at that time. (Republic vs. SB, et al., supra.).

9. AQUINO, JR. V ENRILE

Martial Law Habeas Corpus Power of the President to Order Arrests

Enrile (then Minister of National Defense), pursuant to the order of Marcos issued

and ordered the arrest of a number of individuals including Benigno Aquino Jr even

without any charge against them. Hence, Aquino and some others filed for habeas

corpus against Juan Ponce Enrile. Enriles answer contained a common and special

affirmative defense that the arrest is valid pursuant to Marcos declaration of Martial

Law.

ISSUE: Whether or not Aquinos detention is legal in accordance to the declaration

of Martial Law.

HELD: The Constitution provides that in case of invasion, insurrection or rebellion,

or imminent danger against the state, when public safety requires it, the President

may suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus or place the Philippines or

any part therein under Martial Law. In the case at bar, the state of rebellion plaguing

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

the country has not yet disappeared, therefore, there is a clear and imminent

danger against the state. The arrest is then a valid exercise pursuant to the

Presidents order.

10. JAVELLANA V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY

50 SCRA 30 Political law Constitutional Law Political Question Validity of the

1973 Constitution Restriction to Judicial Power

In 1973, Marcos ordered the immediate implementation of the new 1973

Constitution. Javellana, a Filipino and a registered voter sought to enjoin the Exec

Sec and other cabinet secretaries from implementing the said constitution. Javellana

averred that the said constitution is void because the same was initiated by the

president. He argued that the President is w/o power to proclaim the ratification by

the Filipino people of the proposed constitution. Further, the election held to ratify

such constitution is not a free election there being intimidation and fraud.

ISSUE: Whether or not the SC must give due course to the petition.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

HELD: The SC ruled that they cannot rule upon the case at bar. Majority of the SC

justices expressed the view that they were concluded by the ascertainment made

by the president of the Philippines, in the exercise of his political prerogatives.

Further, there being no competent evidence to show such fraud and intimidation

during the election, it is to be assumed that the people had acquiesced in or

accepted the 1973 Constitution. The question of the validity of the 1973

Constitution is a political question which was left to the people in their sovereign

capacity to answer. Their ratification of the same had shown such acquiescence.

11. OCCENA V. COMELEC

G.R. No. L-56350 April 2, 1981

Fernando, C.J.

Facts:

Petitioners Samuel Occena and Ramon A. Gonzales, both members of the

Philippine Bar and former delegates to the 1971 Constitutional Convention that

framed the present Constitution, are suing as taxpayers. The rather unorthodox

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

aspect of these petitions is the assertion that the 1973 Constitution is not the

fundamental law, the Javellana ruling to the contrary notwithstanding.

Issue:

What is the power of the Interim Batasang Pambansa to propose

amendments and how may it be exercised? More specifically as to the latter, what is

the extent of the changes that may be introduced, the number of votes necessary

for the validity of a proposal, and the standard required for a proper submission?

Held:

The applicable provision in the 1976 Amendments is quite explicit. Insofar

as pertinent it reads thus: The Interim Batasang Pambansa shall have the same

powers and its Members shall have the same functions, responsibilities, rights,

privileges, and disqualifications as the interim National Assembly and the regular

National Assembly and the Members thereof. One of such powers is precisely that

of proposing amendments. The 1973 Constitution in its Transitory Provisions vested

the Interim National Assembly with the power to propose amendments upon special

call by the Prime Minister by a vote of the majority of its members to be ratified in

accordance with the Article on Amendments. When, therefore, the Interim Batasang

Pambansa, upon the call of the President and Prime Minister Ferdinand E. Marcos,

met as a constituent body its authority to do so is clearly beyond doubt. It could and

did propose the amendments embodied in the resolutions now being assailed. It

may be observed parenthetically that as far as petitioner Occena is concerned, the

question of the authority of the Interim Batasang Pambansa to propose

amendments is not new. Considering that the proposed amendment of Section 7 of

Article X of the Constitution extending the retirement of members of the Supreme

Court and judges of inferior courts from sixty-five (65) to seventy (70) years is but a

restoration of the age of retirement provided in the 1935 Constitution and has been

intensively and extensively discussed at the Interim Batasang Pambansa, as well as

through the mass media, it cannot, therefore, be said that our people are unaware

of the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed amendment.

Issue:

Were the amendments proposed are so extensive in character that they

go far beyond the limits of the authority conferred on the Interim Batasang

Pambansa as Successor of the Interim National Assembly? Was there revision rather

than amendment?

Held:

Whether the Constitutional Convention will only propose amendments to

the Constitution or entirely overhaul the present Constitution and propose an

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

entirely new Constitution based on an Ideology foreign to the democratic system, is

of no moment; because the same will be submitted to the people for ratification.

Once ratified by the sovereign people, there can be no debate about the validity of

the new Constitution. The fact that the present Constitution may be revised and

replaced with a new one is no argument against the validity of the law because

amendment includes the revision or total overhaul of the entire Constitution. At

any rate, whether the Constitution is merely amended in part or revised or totally

changed would become immaterial the moment the same is ratified by the

sovereign people.

Issue:

What is the vote necessary to propose amendments as well as the

standard for proper submission?

Held:

The Interim Batasang Pambansa, sitting as a constituent body, can

propose amendments. In that capacity, only a majority vote is needed. It would be

an indefensible proposition to assert that the three-fourth votes required when it

sits as a legislative body applies as well when it has been convened as the agency

through which amendments could be proposed. That is not a requirement as far as

a constitutional convention is concerned. It is not a requirement either when, as in

this case, the Interim Batasang Pambansa exercises its constituent power to

propose amendments. Moreover, even on the assumption that the requirement of

three- fourth votes applies, such extraordinary majority was obtained. It is not

disputed that Resolution No. 1 proposing an amendment allowing a natural-born

citizen of the Philippines naturalized in a foreign country to own a limited area of

land for residential purposes was approved by the vote of 122 to 5; Resolution No. 2

dealing with the Presidency, the Prime Minister and the Cabinet, and the National

Assembly by a vote of 147 to 5 with 1 abstention; and Resolution No. 3 on the

amendment to the Article on the Commission on Elections by a vote of 148 to 2 with

1 abstention. Where then is the alleged infirmity? As to the requisite standard for a

proper submission, the question may be viewed not only from the standpoint of the

period that must elapse before the holding of the plebiscite but also from the

standpoint of such amendments having been called to the attention of the people

so that it could not plausibly be maintained that they were properly informed as to

the proposed changes. As to the period, the Constitution indicates the way the

matter should be resolved. There is no ambiguity to the applicable provision: Any

amendment to, or revision of, this Constitution shall be valid when ratified by a

majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite which shall be held not later than three

months after the approval of such amendment or revision. The three resolutions

were approved by theInterim Batasang Pambansa sitting as a constituent assembly

on February 5 and 27, 1981. In the Batasang Pambansa Blg. 22, the date of the

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

plebiscite is set for April 7, 1981. It is thus within the 90-day period provided by the

Constitution.

12. PHILIPPINE BAR ASSOCIATION VS. COMELEC

140 SCRA 455

January 7, 1986

FACTS:

11 petitions were filed for prohibition against the enforcement of BP 883 which calls

for special national elections on February 7, 1986 (Snap elections) for the offices of

President and Vice President of the Philippines. BP 883 in conflict with the

constitution in that it allows the President to continue holding office after the calling

of the special election.

Senator Pelaez submits that President Marcos letter of conditional resignation did

not create the actual vacancy required in Section 9, Article 7 of the Constitution

which could be the basis of the holding of a special election for President and Vice

President earlier than the regular elections for such positions in 1987. The letter

states that the President is: irrevocably vacat(ing) the position of President

effective only when the election is held and after the winner is proclaimed and

qualified as President by taking his oath office ten (10) days after his proclamation.

The unified opposition, rather than insist on strict compliance with the cited

constitutional provision that the incumbent President actually resign, vacate his

office and turn it over to the Speaker of the Batasang Pambansa as acting President,

their standard bearers have not filed any suit or petition in intervention for the

purpose nor repudiated the scheduled election. They have not insisted that

President Marcos vacate his office, so long as the election is clean, fair and honest.

ISSUE:

Is BP 883 unconstitutional, and should the Supreme Court therefore stop and

prohibit the holding of the elections

HELD:

The petitions in these cases are dismissed and the prayer for the issuance of an

injunction restraining respondents from holding the election on February 7, 1986, in

as much as there are less than the required 10 votes to declare BP 883

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

unconstitutional.

The events that have transpired since December 3,as the Court did not issue any

restraining order, have turned the issue into a political question (from the purely

justiciable issue of the questioned constitutionality of the act due to the lack of the

actual vacancy of the Presidents office) which can be truly decided only by the

people in their sovereign capacity at the scheduled election, since there is no issue

more political than the election. The Court cannot stand in the way of letting the

people decide through their ballot, either to give the incumbent president a new

mandate or to elect a new president.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

13. LAWYERS LEAGUE FOR A BETTER PHILIPPINES vs. AQUINO

(G.R. No. 73748 - May 22, 1986)

-----------------------(There is no "Full-Text" of this case. This is a Minute Resolution made by the SC.)

Minute Resolutions

EN BANC

[G.R. No. 73748, May 22, 1986]

LAWYERS LEAGUE FOR A BETTER PHILIPPINES AND/OR OLIVER A. LOZANO VS.

PRESIDENT CORAZON C. AQUINO, ET AL.

SIRS/MESDAMES:

Quoted hereunder, for your information, is a resolution of this Court MAY 22, 1986.

In G.R. No. 73748, Lawyers League for a Better Philippines vs. President Corazon C.

Aquino, et al.; G.R. No. 73972, People's Crusade for Supremacy of the Constitution

vs. Mrs. Cory Aquino, et al., and G.R. No. 73990, Councilor Clifton U. Ganay vs.

Corazon C. Aquino, et al., the legitimacy of the government of President Aquino is

questioned. It is claimed that her government is illegal because it was not

established pursuant to the 1973 Constitution.

As early as April 10, 1986, this Court* had already voted to dismiss the petitions for

the reasons to be stated below. On April 17, 1986, Atty. Lozano as counsel for the

petitioners in G.R. Nos. 73748 and 73972 withdrew the petitions and manifested

that they would pursue the question by extra-judicial methods. The withdrawal is

functus oficio.

The three petitions obviously are not impressed with merit. Petitioners have no

personality to sue and their petitions state no cause of action. For the legitimacy of

the Aquino government is not a justiciable matter. It belongs to the realm of politics

where only the people of the Philippines are the judge. And the people have made

the judgment; they have accepted the government of President Corazon C. Aquino

which is in effective control of the entire country so that it is not merely a de

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

factogovernment but is in fact and law a de jure government. Moreover, the

community of nations has recognized the legitimacy of the present government. All

the eleven members of this Court, as reorganized, have sworn to uphold the

fundamental law of the Republic under her government.

In view of the foregoing, the petitions are hereby dismissed.

Very truly yours,

(Sgd.) GLORIA C. PARAS

Clerk of Court

* The Court was then composed of Teehankee, C.J. and Abad Santos., MelencioHerrera, Plana, Escolin, Gutierrez, Jr., Cuevas, Alampay and Patajo,

JJ.-----------------------------------------DIGEST

FACTS:

On February 25, 1986, President Corazon Aquino issued Proclamation No. 1

announcing that she and Vice President Laurel were taking power.

On March 25, 1986, proclamation No.3 was issued providing the basis of the Aquino

government assumption of power by stating that the "new government was

installed through a direct exercise of the power of the Filipino people assisted by

units of the New Armed Forces of the Philippines."

ISSUE:

Whether or not the government of Corazon Aquino is legitimate.

HELD:

Yes. The legitimacy of the Aquino government is not a justiciable matter but belongs

to the realm of politics where only the people are the judge.

The Court further held that:

The people have accepted the Aquino government which is in effective control of

the entire country;

It is not merely a de facto government but in fact and law a de jure government;

and

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

The community of nations has recognized the legitimacy of the new government.

14. IN RE BERMUDEZ no digest found haha short case

15. IN RE: LETTER OF ASSOCIATE JUSTICE REYNATO S. PUNO

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Facts:

o The petitioner, Reynato S. Puno, was first appointed as Associate Justice of

the Court of Appeals on 1980.

o On 1983, the Court of Appeals was reorganized and became the Intermediate

Appellate Court pursuant to BP Blg. 129.

o On 1984, petitioner was appointed to be Deputy Minister of Justice in the

Ministry of Justice. Thus, he ceased to be a member of the Judiciary.

o After February 1986 EDSA Revolution, there was a reorganization of the entire

government, including the Judiciary.

o A Screening Committee for the reorganization of the Intermediate Appelate

Court and lower courts recommended the return of petitioner as Associate

Justice of the new court of Appeals and assigned him the rank of number 11

in the roster of appellate court justices.

o When the appointments were signed by Pres. Aquino, petitioner's seniority

ranking changes from number 11 to 26.

o Then, petitioner alleged that the change in seniority ranking was due to

"inadvertence" of the President, otherwise, it would run counter to the

provisions of Section 2 of E.O. No. 33.

o Petitioner Justice Reynato S. Puno wrote a letter to the Court seeking the

correction of his seniority ranking in the Court of Appeals.

o The Court en banc granted Justice Puno's request.

o A motion for reconsideration was later filed by Associate Justices Campos Jr.

and Javellana who are affected by the ordered correction.

o They alleged that petitioner could not claim reappointment because the

courts where he had previously been appointed ceased to exist at the date of

his last appointment.

Issue: WON the present Court of Appeals is merely a continuation of the old Court

of Appeals and Intermediate Appellate Court existing before the promulgation of

E.O. No. 33.

Held:

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

The Court held that the Court of Appeals and Intermediate Appellate Court existing

prior to E.O. No. 33 phased out as part of the legal system abolished by the 1987

Revolution. The Court of Appeals that was established under E.O. No. 33 is

considered as an entirely new court.

The present Court of Appeals is a new entity, different and distinct from the courts

existing before E.O. No. 33. It was created in the wake of the massive reorganization

launched by the revolutionary government of Corazon Aquino in the aftermath of

the people power in 1986.

Revolution is defined as "the complete overthrow of the established government in

any country or state by those who were previously subject to it." or "as sudden.

radical and fundamental change in the government or political system, usually

effected with violence or at least some acts of violence."

16. DE LEON V. ESGUERRA

De Leon v. Esguerra, 153 SCRA 602, August, 31, 1987

(En Banc), J. Melencio-Herrera

Facts: On May 17, 1982, petitioner Alfredo M. De Leon was elected Barangay

Captain together with the other petitioners as Barangay Councilmen of Barangay

Dolores, Muncipality of Taytay, Province of Rizal in a Barangay election held under

Batas Pambansa Blg. 222, otherwise known as Barangay Election Act of 1982.

On February 9, 1987, petitioner De Leon received a Memorandum antedated

December 1, 1986 but signed by respondent OIC Governor Benjamin Esguerra on

February 8, 1987 designating respondent Florentino G. Magno as Barangay Captain

of Barangay Dolores and the other respondents as members of Barangay Council of

the same Barangay and Municipality.

Petitoners prayed to the Supreme Court that the subject Memoranda of February 8,

1987 be declared null and void and that respondents be prohibited by taking over

their positions of Barangay Captain and Barangay Councilmen.

Petitioners maintain that pursuant to Section 3 of the Barangay Election Act of 1982

(BP Blg. 222), their terms of office shall be six years which shall commence on June

7, 1988 and shall continue until their successors shall have elected and shall have

qualified. It was also their position that with the ratification of the 1987 Philippine

Constitution, respondent OIC Governor no longer has the authority to replace them

and to designate their successors.

On the other hand, respondents contend that the terms of office of elective and

appointive officials were abolished and that petitioners continued in office by virtue

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

of Sec. 2, Art. 3 of the Provisional Constitution and not because their term of six

years had not yet expired; and that the provision in the Barangay Election Act fixing

the term of office of Barangay officials to six years must be deemed to have been

repealed for being inconsistent with Sec. 2, Art. 3 of the Provisional Constitution.

Issue: Whether or not the designation of respondents to replace petitioners was

validly made during the one-year period which ended on Feb 25, 1987.

Ruling: Supreme Court declared that the Memoranda issued by respondent OIC

Gov on Feb 8, 1987 designating respondents as Barangay Captain and Barangay

Councilmen of Barangay Dolores, Taytay, Rizal has no legal force and effect.

The 1987 Constitution was ratified in a plebiscite on Feb 2, 1987, therefore, the

Provisional Constitution must be deemed to have superseded. Having become

inoperative, respondent OIC Gov could no longer rely on Sec 2, Art 3, thereof to

designate respondents to the elective positions occupied by petitioners. Relevantly,

Sec 8, Art 1 of the 1987 Constitution further provides in part:

"Sec. 8. The term of office of elective local officials, except barangay officials, which

shall be determined by law, shall be three years x x x."

Until the term of office of barangay officials has been determined by aw, therefore,

the term of office of 6 years provided for in the Barangay Election Act of 1982

should still govern.

17. GONZALES V. COMELEC

21 SCRA 774 Political Law Amendment to the Constitution Political Question vs

Justiciable Question

FACTS: In June 1967, Republic Act 4913 was passed. This law provided for the

COMELEC to hold a plebiscite for the proposed amendments to the Constitution. It

was provided in the said law that the plebiscite shall be held on the same day that

the general national elections shall be held (November 14, 1967). This was

questioned by Ramon Gonzales and other concerned groups as they argued that

this was unlawful as there would be no proper submission of the proposals to the

people who would be more interested in the issues involved in the general election

rather than in the issues involving the plebiscite.

Gonzales also questioned the validity of the procedure adopted by Congress when

they came up with their proposals to amend the Constitution (RA 4913). In this

regard, the COMELEC and other respondents interposed the defense that said act of

Congress cannot be reviewed by the courts because it is a political question.

ISSUE:

I. Whether or not the act of Congress in proposing amendments is a political

question.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

II. Whether or not a plebiscite may be held simultaneously with a general election.

HELD:

I. No. The issue is a justiciable question. It must be noted that the power to amend

as well as the power to propose amendments to the Constitution is not included in

the general grant of legislative powers to Congress. Such powers are not

constitutionally granted to Congress. On the contrary, such powers are inherent to

the people as repository of sovereignty in a republican state. That being, when

Congress makes amendments or proposes amendments, it is not actually doing so

as Congress; but rather, it is sitting as a constituent assembly. Such act is not a

legislative act. Since it is not a legislative act, it is reviewable by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court has the final say whether or not such act of the constituent

assembly is within constitutional limitations.

II. Yes. There is no prohibition to the effect that a plebiscite must only be held on a

special election. SC held that there is nothing in this provision of the [1935]

Constitution to indicate that the election therein referred to is a special, not a

general election. The circumstance that the previous amendment to the

Constitution had been submitted to the people for ratification in special elections

merely shows that Congress deemed it best to do so under the circumstances then

obtaining. It does not negate its authority to submit proposed amendments for

ratification in general elections.

Note: **Justice Sanchez and Justice JBL Reyes dissented. Plebiscite should be

scheduled on a special date so as to facilitate Fair submission, intelligent

consent or rejection. They should be able to compare the original proposition

with the amended proposition.

18. SANTIAGO, ET AL V. COMELEC

March/June 1997

Amendment to the Constitution

FACTS: On 6 Dec 1996, Atty. Jesus S. Delfin filed with COMELEC a Petition to

Amend the Constitution to Lift Term Limits of elective Officials by Peoples Initiative

The COMELEC then, upon its approval, a.) set the time and dates for signature

gathering all over the country, b.) caused the necessary publication of the said

petition in papers of general circulation, and c.) instructed local election registrars

to assist petitioners and volunteers in establishing signing stations. On 18 Dec

1996, MD Santiago et al filed a special civil action for prohibition against the Delfin

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

Petition. Santiago argues that 1.) the constitutional provision on peoples initiative

to amend the constitution can only be implemented by law to be passed by

Congress and no such law has yet been passed by Congress, 2.) RA 6735 indeed

provides for three systems of initiative namely, initiative on the Constitution, on

statues and on local legislation. The two latter forms of initiative were specifically

provided for in Subtitles II and III thereof but no provisions were specifically made

for initiatives on the Constitution. This omission indicates that the matter of

peoples initiative to amend the Constitution was left to some future law as

pointed out by former Senator Arturo Tolentino.

ISSUE: Whether or not RA 6735 was intended to include initiative on amendments

to the constitution and if so whether the act, as worded, adequately covers such

initiative.

HELD: RA 6735 is intended to include the system of initiative on amendments to

the constitution but is unfortunately inadequate to cover that system. Sec 2 of

Article 17 of the Constitution provides: Amendments to this constitution may

likewise be directly proposed by the people through initiative upon a petition of at

least twelve per centum of the total number of registered voters, of which every

legislative district must be represented by at least there per centum of the

registered voters therein. . . The Congress shall provide for the implementation of

the exercise of this right This provision is obviously not self-executory as it needs

an enabling law to be passed by Congress. Joaquin Bernas, a member of the 1986

Con-Con stated without implementing legislation Section 2, Art 17 cannot operate.

Thus, although this mode of amending the constitution is a mode of amendment

which bypasses Congressional action in the last analysis is still dependent on

Congressional action. Bluntly stated, the right of the people to directly propose

amendments to the Constitution through the system of inititative would remain

entombed in the cold niche of the constitution until Congress provides for its

implementation. The people cannot exercise such right, though constitutionally

guaranteed, if Congress for whatever reason does not provide for its

implementation.

***Note that this ruling has been reversed on November 20, 2006 when ten

justices of the SC ruled that RA 6735 is adequate enough to enable such initiative.

HOWEVER, this was a mere minute resolution which reads in part:

Ten (10) Members of the Court reiterate their position, as shown by their various

opinions already given when the Decision herein was promulgated, that Republic

Act No. 6735 is sufficient and adequate to amend the Constitution thru a peoples

initiative.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

19. LAMBINO V. COMELEC

Amendment vs Revision

FACTS: Lambino was able to gather the signatures of 6,327,952 individuals for an

initiative petition to amend the 1987 Constitution. That said number of votes

comprises at least 12 per centum of all registered voters with each legislative

district at least represented by at least 3 per centum of its registered voters. This

has been verified by local COMELEC registrars as well. The proposed amendment to

the constitution seeks to modify Secs 1-7 of Art VI and Sec 1-4 of Art VII and by

adding Art XVIII entitled Transitory Provisions. These proposed changes will shift

the president bicameral-presidential system to a Unicameral-Parliamentary form of

government. The COMELEC, on 31 Aug 2006, denied the petition of the Lambino

group due to the lack of an enabling law governing initiative petitions to amend the

Constitution this is in pursuant to the ruling in Santiago vs COMELEC. Lambino et

al contended that the decision in the aforementioned case is only binding to the

parties within that case.

ISSUE: Whether or not the petition for initiative met the requirements of Sec 2

ArtXVII of the 1987 Constitution.

HELD: The proponents of the initiative secure the signatures from the people. The

proponents secure the signatures in their private capacity and not as public

officials. The proponents are not disinterested parties who can impartially explain

the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed amendments to the people.

The proponents present favorably their proposal to the people and do not present

the arguments against their proposal. The proponents, or their supporters, often

pay those who gather the signatures. Thus, there is no presumption that the

proponents observed the constitutional requirements in gathering the signatures.

The proponents bear the burden of proving that they complied with the

constitutional requirements in gathering the signatures that the petition

contained, or incorporated by attachment, the full text of the proposed

amendments. The proponents failed to prove that all the signatories to the

proposed amendments were able to read and understand what the petition

contains. Petitioners merely handed out the sheet where people can sign but they

did not attach thereto the full text of the proposed amendments.

Lambino et al are also actually proposing a revision of the constitution and not a

mere amendment. This is also in violation of the logrolling rule wherein a proposed

amendment should only contain one issue. The proposed amendment/s by

petitioners even includes a transitory provision which would enable the would-be

parliament to enact more rules.

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW REVIEW CASE DIGEST 1

There is no need to revisit the Santiago case since the issue at hand can be decided

upon other facts. The rule is, the Court avoids questions of constitutionality so long

as there are other means to resolve an issue at bar.

***NOTE: On November 20, 2006 in a petition for reconsideration submitted by the

Lambino Group 10 (ten) Justices of the Supreme Court voted that Republic Act 6735

is adequate.

HOWEVER, this was a mere minute resolution which reads in part:

Ten (10) Members of the Court reiterate their position, as shown by their various

opinions already given when the Decision herein was promulgated, that Republic

Act No. 6735 is sufficient and adequate to amend the Constitution thru a peoples

initiative.

20. TOLENTINO V. COMELEC

41 SCRA 702 Political Law Amendment to the Constitution Doctrine of Proper

Submission

FACTS: The Constitutional Convention of 1971 scheduled an advance plebiscite

concerning only the proposal to lower the voting age from 21 to 18. This was even

before the rest of the draft of the Constitution (then under revision) had been

approved. Arturo Tolentino then filed a motion to prohibit such plebiscite.

ISSUE: Whether or not the petition will prosper.

HELD: Yes. If the advance plebiscite will be allowed, there will be an improper

submission to the people. Such is not allowed.

The proposed amendments shall be approved by a majority of the votes cast at an

election at which the amendments are submitted to the people for ratification.

Election here is singular which meant that the entire constitution must be submitted