Professional Documents

Culture Documents

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 151, Docket 85-2155

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 151, Docket 85-2155

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

790 F.

2d 260

Warren BASS, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

Saul A. JACKSON, Nassau County Commissioner of

Corrections;

"John" Waters, Lt. For Security, Nassau County Correctional

Center; "Jack" Spinner, Correctional Officer, First Class,

Nassau County Correctional Center; "Frank Smith," M.D.;

"Ed Jones," M.D.; and Walter J. Flood, Warden, Nassau

County Correctional Center, Defendants-Appellees.

No. 151, Docket 85-2155.

United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit.

Submitted Oct. 23, 1985.

Decided May 13, 1986.

Warren Bass, pro se.

Edward G. McCabe, Co. Atty. of Nassau County, Mineola, N.Y. (Robert

O. Boyhan, Deputy Co. Atty., Mineola, N.Y., of counsel), for defendantsappellees.

Before PIERCE, WINTER and MINER, Circuit Judges.

WINTER, Circuit Judge:

Plaintiff Warren Bass appeals from the district court's dismissal of his

complaint brought under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983. Bass, a pretrial detainee in the

Nassau County Correctional Center ("NCCC"), brought this action against Saul

Jackson, Nassau County Commissioner of Corrections, Walter J. Flood,

Warden of NCCC, John Waters, a supervising officer at NCCC, Jack Spinner, a

Corrections Officer with supervisory authority in the D floor at NCCC, and two

doctors described as "Frank Smith" and "Ed Jones." Bass alleged that the

defendants did not properly protect him in known dangerous conditions, that as

a result he had liquid ammonia thrown in his face by fellow inmates, and that

the defendants subsequently provided inadequate medical care. We reverse in

part and affirm in part.

2

We begin by restating the allegations of Bass' complaint, which of course we

assume to be true for purposes of this appeal. Bass and detainee Rhoden were

incarcerated in protective custody cell block D-3. The block had for some

months been "run" by inmates Banks, Durant, and Zavarro. Because Rhoden

had often questioned the latter's authority, a hostile atmosphere had developed.

Other allegations indicate that the trouble between Rhoden and others had been

made known to the prison authorities. Shortly before the events in question,

moreover, Banks had surrendered a homemade knife to Spinner in a meeting at

which the two discussed a dispute over where Rhoden should be housed.

On the morning of November 25, Rhoden, Banks and Durant became involved

in an argument that was interrupted by lunch. After lunch, plaintiff went to the

cell of inmate Cole. The morning's argument resumed, with Rhoden eventually

walking away from the argument towards Cole's cell. As he was about to enter

the open cell, he was struck from behind by Banks, while Durant picked up a

metal mop wringer and menaced Rhoden with it.

At this point, Banks and Durant began throwing various objects at Rhoden, and

taunted him to come out. Plaintiff and Cole were trapped in Cole's cell by these

activities in the cell doorway. Soon afterward, Banks slammed the door shut,

locking plaintiff, Rhoden, and Cole in the cell. Banks and Durant then obtained

a quart bottle of ammonia from Zavarro, filled two cups with the ammonia, and

threw the liquid on the three inmates trapped in the cell. Plaintiff and Rhoden

were struck in the face by the ammonia and began calling for a Corrections

Officer. None appeared for two to three minutes, despite the fact that an officer

is supposed to be stationed in the "lock box" area, within twenty feet of Cole's

cell, at all times.

When officers did arrive, they instructed the plaintiff and Rhoden to get into

the shower. Rhoden collapsed and had to be carried into the shower; plaintiff

rinsed himself off and flushed his eyes in the shower. According to the

complaint, the two inmates were then taken to NCCC's medical section, where

they were given a cursory physical examination and left sitting on a bench for

five to six hours. There was no physician on duty at the NCCC, and they were

eventually transported to the emergency room at the Nassau County Medical

Center. At the Medical Center, plaintiff's eyes were properly flushed and

examined by an ophthalmologist, who determined that the ammonia had caused

"irisitis," an inflammation of the iris. Eyedrops were prescribed and

administered.

Plaintiff alleges that since returning to the jail he has experienced redness,

tearing, and itching in both eyes, and cannot read for long periods of time,

conditions that did not exist before the incident. Plaintiff further alleges that his

requests for sick-call have not been honored, and his requests to see an

ophthalmologist have been denied. He therefore has brought this suit for

damages and injunctive relief.

The case was assigned to Magistrate Jordan who ordered that discovery be

completed by May 17. Nevertheless, the district court held a hearing on April

11 and thereafter dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim for relief

under Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6). Bass raises numerous claims of unfairness and

lack of notice, none of which we reach because we conclude that Bass'

complaint states a claim on which relief may be granted.

On a 12(b)(6) motion, the complaint should not be dismissed "unless it appears

beyond doubt that the plaintiff can prove no set of facts in support of his claim

which would entitle him to relief." Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5, 10, 101 S.Ct.

173, 176, 66 L.Ed.2d 163 (1980) (per curiam). Pro se complaints, moreover,

are held "to less stringent standards than formal pleadings drafted by lawyers,"

Haines v. Kerner, 404 U.S. 519, 520, 92 S.Ct. 594, 596, 30 L.Ed.2d 652 (1972)

(per curiam), and we have held that "a federal judge should not dismiss a

prisoner's pro se, in forma pauperis claim as frivolous unless statute or

controlling precedent clearly forecloses the pleading, liberally construed."

Cameron v. Fogarty, 705 F.2d 676, 678 (2d Cir.1983).

Bass makes two distinct constitutional claims. First, he alleges a failure to

protect him from physical harm in violation of his constitutional rights under

the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court has recently made

clear that the Due Process Clause is "not implicated by a negligent act of an

official causing unintended loss of or injury to life, liberty or property." Daniels

v. Williams, --- U.S. ----, 106 S.Ct. 662, 663, 88 L.Ed.2d 662 (1986) (emphasis

in original). That case explicitly did not consider whether something less than

intentional conduct, such as recklessness or gross negligence, is enough to

trigger the protections of the Due Process Clause. Id., 106 S.Ct. at 667 n. 3. In

the absence of further guidance, we must adhere to our recently restated

position that

10 isolated omission to act by a state prison guard does not support a claim under

[a]n

section 1983 absent circumstances indicating an evil intent, or recklessness, or at

least deliberate indifference to the consequences of his conduct for those under his

control and dependent upon him.

11

Ayers v. Coughlin, 780 F.2d 205, 209 (2d Cir.1985) (quoting Williams v.

Vincent, 508 F.2d 541, 546 (2d Cir.1974)).

12

Under this test, we cannot say that Bass can prove no set of facts in support of a

claim of deliberate indifference on the part of some defendants. The claim that

the block had been "run" by inmates hostile to Rhoden, the knowledge of

corrections officers of this ongoing hostility, the dispute over Rhoden's location

in the prison, and the presence of weapons are enough to raise questions of fact

as to what the correctional officers knew and when they knew it. Bass'

allegations are thin, but the liberal rules regarding pro se pleadings compel us to

hold that Bass has stated a claim that may, with the aid of discovery, show

deliberate indifference on the part of correctional officials to pending violence

in Block D-3.

13

However, respondeat superior liability does not lie against corrections officers

in Section 1983 actions. McKinnon v. Patterson, 568 F.2d 930, 934 (2d

Cir.1977), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 1087, 98 S.Ct. 1282, 55 L.Ed.2d 792 (1978).

A plaintiff must thus allege a tangible connection between the acts of a

defendant and the injuries suffered. Under that standard, plaintiff has failed to

allege such acts by defendants Jackson and Flood. His allegations with regard to

the inadequacy of the prison regulations are too conclusory to withstand a

motion to dismiss, and neither Jackson nor Flood are otherwise implicated in

the events in question. His descriptions of the authority and responsibility of

Waters and Spinner, however, are sufficient to implicate them in his claim of

deliberate indifference.

14

Plaintiff's second claim is that he suffered a deprivation of adequate medical

care serious enough to be of a constitutional nature. Under Estelle v. Gamble,

429 U.S. 97, 105, 97 S.Ct. 285, 291, 50 L.Ed.2d 251 (1976), "deliberate

indifference to a prisoner's serious illness or injury states a cause of action

under Sec. 1983." Although Bass' pro se account of events may amount to an

allegation of deliberate indifference, he does not connect the failure to obtain

prompt medical care to any of the correctional or medical defendants. This

claim must, therefore, be dismissed. Whether the harm suffered from the

alleged lack of medical care may be recovered as proximately resulting from

the earlier incident alleged is not now before us.

15

No allegation of the complaint supports a claim against Doctors Smith or Jones,

and the dismissal is affirmed as to them.

16

In conclusion, we reverse on Bass' claims against Waters and Spinner. We

16

affirm as to the dismissal of the complaint against Jackson, Flood, Smith and

Jones.

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Payn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Document8 pagesPayn v. Kelley, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs50% (2)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Wilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesWilson v. Dowling, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Greene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesGreene v. Tennessee Board, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesBrown v. Shoe, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthglenn Gunther Toody's v. HQ8-10410-10450, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Webb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document18 pagesWebb v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Peter Wilkinson CV 1Document3 pagesPeter Wilkinson CV 1larry3108No ratings yet

- Rebranding Brief TemplateDocument8 pagesRebranding Brief TemplateRushiraj Patel100% (1)

- Expert Business Analyst Darryl Cropper Seeks New OpportunityDocument8 pagesExpert Business Analyst Darryl Cropper Seeks New OpportunityRajan GuptaNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileDocument4 pagesCase Analysis - Compania de Telefonos de ChileSubrata BasakNo ratings yet

- Code Description DSMCDocument35 pagesCode Description DSMCAnkit BansalNo ratings yet

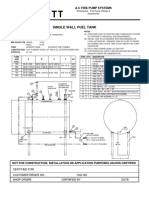

- Single Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump SystemsDocument1 pageSingle Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump Systemsricardo cardosoNo ratings yet

- Collaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFDocument32 pagesCollaboration Live User Manual - 453562037721a - en - US PDFIvan CvasniucNo ratings yet

- Basic Electrical Design of A PLC Panel (Wiring Diagrams) - EEPDocument6 pagesBasic Electrical Design of A PLC Panel (Wiring Diagrams) - EEPRobert GalarzaNo ratings yet

- Growatt SPF3000TL-HVM (2020)Document2 pagesGrowatt SPF3000TL-HVM (2020)RUNARUNNo ratings yet

- Logistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSDocument20 pagesLogistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSJenishNo ratings yet

- (Free Scores - Com) - Stumpf Werner Drive Blues en Mi Pour La Guitare 40562 PDFDocument2 pages(Free Scores - Com) - Stumpf Werner Drive Blues en Mi Pour La Guitare 40562 PDFAntonio FresiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: The Investment Environment: Problem SetsDocument5 pagesChapter 1: The Investment Environment: Problem SetsGrant LiNo ratings yet

- EFM2e, CH 03, SlidesDocument36 pagesEFM2e, CH 03, SlidesEricLiangtoNo ratings yet

- De Thi Chuyen Hai Duong 2014 2015 Tieng AnhDocument4 pagesDe Thi Chuyen Hai Duong 2014 2015 Tieng AnhHuong NguyenNo ratings yet

- TX Set 1 Income TaxDocument6 pagesTX Set 1 Income TaxMarielle CastañedaNo ratings yet

- CST Jabber 11.0 Lab GuideDocument257 pagesCST Jabber 11.0 Lab GuideHải Nguyễn ThanhNo ratings yet

- Novirost Sample TeaserDocument2 pagesNovirost Sample TeaserVlatko KotevskiNo ratings yet

- Server LogDocument5 pagesServer LogVlad CiubotariuNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship WholeDocument20 pagesEntrepreneurship WholeKrizztian SiuaganNo ratings yet

- Excavator Loading To Truck TrailerDocument12 pagesExcavator Loading To Truck TrailerThy RonNo ratings yet

- Advanced Real-Time Systems ARTIST Project IST-2001-34820 BMW 2004Document372 pagesAdvanced Real-Time Systems ARTIST Project IST-2001-34820 BMW 2004كورسات هندسيةNo ratings yet

- 2022 Product Catalog WebDocument100 pages2022 Product Catalog WebEdinson Reyes ValderramaNo ratings yet

- Mba Assignment SampleDocument5 pagesMba Assignment Sampleabdallah abdNo ratings yet

- Project The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDDocument7 pagesProject The Ant Ranch Ponzi Scheme JDmorraz360No ratings yet

- Meanwhile Elsewhere - Lizzie Le Blond.1pdfDocument1 pageMeanwhile Elsewhere - Lizzie Le Blond.1pdftheyomangamingNo ratings yet

- Battery Impedance Test Equipment: Biddle Bite 2PDocument4 pagesBattery Impedance Test Equipment: Biddle Bite 2PJorge PinzonNo ratings yet

- Trinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Document13 pagesTrinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Bernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsDocument3 pagesBernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsJean Marie DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Continuation in Auditing OverviewDocument21 pagesContinuation in Auditing OverviewJayNo ratings yet

- Ata 36 PDFDocument149 pagesAta 36 PDFAyan Acharya100% (2)