Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Collection of Essays

Uploaded by

api-30502021Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Collection of Essays

Uploaded by

api-30502021Copyright:

Available Formats

Collection of Essays : Look through these examples and note the first and last paragraphs.

You will see there is not a formula presented to the reader and most often the thesis or main idea is presented at the very end. Also, note the first line in each paragraph. These are not first, second, third transitions. Transitions are often complete sentences that shift focus. It is okay for a paper to be about ONE thing elaborated in multiple paragraphs. By reading just these first lines you can see the progression of ideas but without the plug-in transitions. Most essay writing, whether it is persuasive or expository, is ALSO personal. That is voice. Strive for the personal. Use this chart, this method, to skim essays you find.

Title and author On Compassion by Barbara Lazear Ascher First line First paragraph The mans grin is less the result of circumstance than dreams of madness. His buttonless shirt, with one sleeve missing, hangs outside the waist of his baggy trousers. Carefully plaited dreadlocks bespeak a better time, long ago. As he crosses Manhattans Seventy-ninth Street, his gait is the shuffle of the forgotten ones held in place by graivty rather than plans. On the corner of Madison Avenue, he stops before a blond baby in an Aprica stroller. The babys mother waits for the light to change and her hands close tighter on the strollers handle as she sees the man approach. First line of each Paragraph Last Paragraph Last Line For the ancient Greeks, drama taught and reinforced compassion within a society. The object of the Greek tragedy was to inspire empathy in the audience so that the common response to the heros fall was: There, but for the grace of God, go I. Could it be that this was the response of the mother who offered the dollar, the French woman who gave the food? Could it be that the homeless, like those ancients, are reminding us of our common humanity? Of course there is a difference. This play doesnt endand the players cant go home.

The others on the corner, five men and women waiting for the crosstown bus, look away. But for now, in this last gasp of autmumn warmth, he is still. His hands continue to dangle at his sides. The mother grows impatient. Was it fear or compassion that motivated the gift? Up the avenue, at Ninety-first Street, there is a small French bread shop where you can sit and eat a buttery over-priced croissant and wash it down with rich cappuccino. The owner of the shop, a moody French woman, emerges from the kitchen with steaming coffee in s Styrofoam cup, and a small paper bag ofof what? Twice I have witnessed this, and twice I have wondered, what compels this woman to feed this man? As winter approaches, the mayor of New York City is moving the homeless off the streets and into Bellevue Hospital. I think the mayors notion is human, but I fear it is something else as well. Like other cities, there is much about Manhattan now that resembles Dickensian London. And yet, it may be that these are the conditions that finally give birth to empathy, the mother of compassion.

Mother Tongue by Amy Tan

I am not a scholar of English or literature. I cannot give you much more than personal opinions on the English language and its variations in this country or others.

I am a writer. Recently, I was made keenly aware of the different Englishes I do use. Just last week, I was walking down the street with my mother, and I again found myself conscious of the English I was using, the English I do use with her. So youll have some idea of what this family talk I heard sounds like, Ill quote what my mother said during a recent conversation which I videotaped and then transcribed. You should know that my mothers expressive command of English blies how much she actually understands. Lately, Ive been giving more thought to the kind of English my mother speaks. I know this for a fact, because when I was growing up, my mothers limited English limited my perception of her. My mother has long realized the limitations of her English as well. And my mother was standing in the back whispering loudly, Why he dont send me check, already two weeks late. And then I said in perfect English, Yes, Im getting rather concerned. Then she began to talk more loudly. We used a similar routine just five days ago, for a situation that was far less humorous. I think my mothers English almost had an effect on limiting my possibilites in life as well. This was understandable. This was true of word analogies I have been thinking about all this lately, about my mothers English, about achievement tests. Fortunately, I happen to be rebellious in nature and enjoy the challenge of disproving assumptions made about me. But it wasnt until 1985 that I finally began to write fiction. Fortunately, for reasons I wont get into today, I later decided I should envision a reader for the stories I would write.

Apart from what any critic had to say about my writing, I knew I had succeeded where it counted when my mother finished reading my book and gave me her verdict: So easy to read.

Broken Gourd by Eunju Namkung Student winner of 2009 Scholastic Writing contest My father, not the type to tell stories, tells only one story. Just one and only story, over and over again. The story is about me, his one and only daughter, and, according to him, the term daughter is up for interpretation. He says I am more son than daughter, but more broken gourd than son.

The story evolves, grows tumors of extra details that has never been there in the years passed. And in the purest form, the story goes: Eunju Namkung, age six, punched Ian Park, age eight, in the nose. And this is a version that has been spoken sometime between then and now: Eunju Namkung, a mere age six, a sweet little kindergartner, was playing with Ian Park, who was in second grade, but had no friends of his own age to play with. And this is a true story that I hear as I grow up. I am ashamed that I am not the girl who my dad speaks so proudly of. Like how he brings home a soccer ball whose seams have frayed. So I play soccer, but can't even score the winning goals. I pick up on violent competition that exists as a subset of soccer games. Like how he goes to Korea and brings home traditional tops at my brother's request and no stuffed animal, against my request. At least the tops, the things that my brother ask for, even though he too is beyond the age of playing with toys, bring harmonious joy to my brother and father. "Beat him." "Spin faster!" I can tell who wins by his growl of victory, as the other one scurries to pick up their immobile, defeated top. The broken gourd can risk a few more cracks. Like how he brings home pink jackets which he thinks I'll wear, but I tell him, No. Whenever I do see pink jackets on the street, puffy with down and warm with embarrassing color, I feel a little colder and the wind strikes me across the face. Like how he brings home remote control mini car racers that are supposed to be mine. I imagine my father bought the cars from a greasy Korean man wearing a black coat that every poor Korean man owns, sporting tough workman gloves with red rubber palms, which when put together, palms thrusting outwards, looks like a baboon's ass. Like how he brings home black bits of rubber in his hair. And one day, he brings home a cane, that special branch. It comes down on me one day and I definitely feel the lightning and the tree. The hook looms above me drawing ellipses in the air as the other half of it colors me purple. Like how my father brings home discord. He doesn't know my brother hit me in the back of my head so hard, so hard my face got numb. I imagine that it was a frightening strike, some sort of blitzing technique that he learned from his friend, Monday Night Football, maybe it was Saturday-Afternoon-Cut-IntoCartoons College Football. At the sound of the collision my mother scurries in, tired. It's funny, because I can only think of the Moses stick. My father brings home newspapers.

"Take these," he sighs. He extends his arms to me. I take them from him and we both linger in front of the doorway for a few seconds. He expects a bow, but he should know that I have stopped bowing years ago. I consider it for a second. I see a girl whose black hair slides off her shoulders and hangs limply from the surface of her scalp. Her bowed head looks like it is hanging from a ceiling. I decide I do not want to bow. I walk away to put his newspapers on the couch, and I can hear him closing the door, taking off his shoes, sighing, Broken gourd.

Shame by Dick Gregory

I never learned hate at home, or shame. I had to go to school for that. I was about seven years old when I got my first big lesson. I was in love with a little girl named Helene Tucker, a lightcomplexioned little girl with pigtails and nice manners. She was always clean and she was smart in school. I think I went to school then mostly to look at her. I brushed my hair and even got me a little old handkerchief. It was a lady's handkerchief, but I didn't want Helene to see me wipe my nose on my hand. The pipes were frozen again, there was no water in the house, but I washed my socks and shirt every night. I'd get a pot, and go over to Mister Ben's grocery store, and stick my pot down into his soda machine and scoop out some chopped ice. By evening the ice melted to water for washing. I got sick a lot that winter because the fire would go out at night before the clothes were dry. In the morning I'd put them on, wet or dry, because they were the only clothes I had.

Everybody's got a Helene Tucker, a symbol of everything you want. I guess I would have gotten over Helene by summertime, but something happened in that classroom that made her face hang in front of me for the next twenty-two years. It was on a Thursday. The teacher thought I was stupid. The teacher thought I was a troublemaker. It was on a Thursday, the day before the Negro payday. I was shaking, scared to death. That's very nice, Helene. That made me feel pretty good. I stood up and raised my hand. "What is it now?" "You forgot me?" She turned toward the blackboard. My daddy said he'd..." "Sit down, Richard, you're disturbing the class." "My daddy said he'd give...fifteen dollars." She turned around and looked mad. "I got it right now, I got it right now, my Daddy gave it to me to turn in today, my daddy said. .." And furthermore," she said, looking right at me, her nostrils getting big and her lips getting thin and her eyes opening wide, "We know you don't have a daddy." Helene Tucker turned around, her eyes full of tears. "Sit down, Richard." And I always thought the teacher kind of liked me. "Where are you going, Richard! " I walked out of school that day, and for a long time I didn't go back very often.

Now there was shame everywhere. It seemed like the whole world had been inside that classroom, everyone had heard what the teacher had said, everyone had turned around and felt sorry for me. There was shame in going to the Worthy Boys Annual Christmas Dinner for you and your kind, because everybody knew what a worthy boy was. Why couldn't they just call it the Boys Annual Dinner-why'd they have to give it a name? There was shame in wearing the brown and orange and white plaid mackinaw' the welfare gave to three thousand boys. Why'd it have to be the same for everybody so when you walked down the street the people could see you were on relief? It was a nice warm mackinaw and it had a hood, and my momma beat me and called me a little rat when she found out I stuffed it in the bottom of a pail full of garbage way over on Cottage Street. There was shame in running over to Mister Ben's at the end of the day and asking for his rotten peaches, there was shame in asking Mrs. Simmons for a spoonful of sugar, there was shame in running out to meet the relief truck. I hated that truck, full of food for you and your kind. I ran into the house and hid when it came. And then I started to sneak through alleys, to take the long way home so the people going into White's Eat Shop wouldn't see me. Yeah, the whole world heard the teacher that day-we all know you don't have a Daddy.

You might also like

- Close Reading ExtractsDocument9 pagesClose Reading ExtractsStarra ClarkeNo ratings yet

- True NarrativeDocument11 pagesTrue NarrativeMERYL JOYCE padigosNo ratings yet

- Emily's Dress and Other Missing ThingsDocument13 pagesEmily's Dress and Other Missing ThingsMacmillan Publishers100% (3)

- Not Poor, Just BrokeDocument4 pagesNot Poor, Just BrokeEunice Criselle Garcia67% (3)

- The Earth, My Butt, and Other Big Round Things - Chapter SamplerDocument24 pagesThe Earth, My Butt, and Other Big Round Things - Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press50% (2)

- Love Child: A Memoir of Family Lost and FoundFrom EverandLove Child: A Memoir of Family Lost and FoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- A Study in Glitter and DeathDocument13 pagesA Study in Glitter and Deathtina_rosario_2No ratings yet

- Shame by Dick GregoryDocument5 pagesShame by Dick GregoryZack OverfieldNo ratings yet

- Kambala 2022 English Trial Paper 1Document20 pagesKambala 2022 English Trial Paper 1Alfred WongNo ratings yet

- A Conversation With My FatherDocument5 pagesA Conversation With My FatherOllie Worden75% (4)

- MonologuesDocument21 pagesMonologueskittykota6No ratings yet

- (WN) Mushoku Tensei v1Document313 pages(WN) Mushoku Tensei v1David MullorNo ratings yet

- In Dreams Begin ResponsibilitiesDocument4 pagesIn Dreams Begin ResponsibilitiesmarbacNo ratings yet

- Coming To WritingDocument11 pagesComing To WritingAmanda Bridget Del SontroNo ratings yet

- Walis Tingting and What Looked Like A Circular Dustpan. She Was Too BusyDocument7 pagesWalis Tingting and What Looked Like A Circular Dustpan. She Was Too BusyKat GawNo ratings yet

- Daughter of Invention, Julia AlvarezDocument5 pagesDaughter of Invention, Julia AlvarezTeodora UdrescuNo ratings yet

- Homeless PrologueDocument381 pagesHomeless PrologueSkyx 5756No ratings yet

- 2011 Student Contests and PublicationsDocument10 pages2011 Student Contests and Publicationsapi-30502021No ratings yet

- Premium Member Gift ListDocument6 pagesPremium Member Gift Listapi-30502021No ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Imitate Characterization SteinbeckDocument1 pageImitate Characterization Steinbeckapi-30502021No ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Exposition and Dramatic Moment Essay With Narrative Voice Three Innocent Teenagers Were Killed When A Drunken Driver MadeDocument8 pagesExposition and Dramatic Moment Essay With Narrative Voice Three Innocent Teenagers Were Killed When A Drunken Driver Madeapi-30502021No ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Daddy's Wicked Parties: The Most Shocking True Story of Child Abuse Ever Told: Skylark Child Abuse True Stories, #2From EverandDaddy's Wicked Parties: The Most Shocking True Story of Child Abuse Ever Told: Skylark Child Abuse True Stories, #2Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Actividad de Ingels 1Document4 pagesActividad de Ingels 1Leydy Maryuri Diossa ReyNo ratings yet

- Prepositions ESL StudentDocument14 pagesPrepositions ESL StudentNilton PereiraNo ratings yet

- Going To VS WillDocument9 pagesGoing To VS WillLas creaciones de albanyNo ratings yet

- Porter, Windows of The Soul Physiognomy in European Culture 1470-1780 by MartinDocument386 pagesPorter, Windows of The Soul Physiognomy in European Culture 1470-1780 by MartinEminNo ratings yet

- DLL 4TH QUARTER 41ST WEEK English IV MARCH 19-23, 2018Document5 pagesDLL 4TH QUARTER 41ST WEEK English IV MARCH 19-23, 2018angeliNo ratings yet

- English File: Answer KeyDocument4 pagesEnglish File: Answer KeyAnastasia ReznichenkoNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic English TestDocument3 pagesDiagnostic English TestnachoarjonaruNo ratings yet

- Ana Milosevic CVDocument2 pagesAna Milosevic CVAnaNo ratings yet

- Philippines - Group 7 DraftDocument12 pagesPhilippines - Group 7 DraftAngelika LazaroNo ratings yet

- 7 Superb Speaking Activities T PDFDocument7 pages7 Superb Speaking Activities T PDFLeena KapoorNo ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument8 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogcleofeNo ratings yet

- Laggui, Xian Zeus D.Document2 pagesLaggui, Xian Zeus D.Don Angelo De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Ta9.Tuyen Chon de Thi HSG - HieuDocument232 pagesTa9.Tuyen Chon de Thi HSG - Hieu30 -Lê Nguyên Anh ThưNo ratings yet

- English 101Document156 pagesEnglish 101JoshueNo ratings yet

- Lexical Peculiarities of Scottish EnglishDocument13 pagesLexical Peculiarities of Scottish EnglishАлияNo ratings yet

- SUCCESS IS VISION - Docx 2022 Speakin Youtube - PDF SISC+PPDocument19 pagesSUCCESS IS VISION - Docx 2022 Speakin Youtube - PDF SISC+PPWilliam Franklyn Miller WilliamNo ratings yet

- Basic Bootcamp S2 #3 Asking Questions in English: Lesson NotesDocument6 pagesBasic Bootcamp S2 #3 Asking Questions in English: Lesson NotesAnup ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Advanced TESOL E-BookDocument59 pagesAdvanced TESOL E-Bookandrea100% (2)

- An IntroductionDocument13 pagesAn IntroductionJawad EQNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Paket CDocument16 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Paket CRestu AbdiyantoroNo ratings yet

- Objective C - Fire An Action After A NSTextField Is Modified in A Cell Based NSTableView - Stack OveDocument269 pagesObjective C - Fire An Action After A NSTextField Is Modified in A Cell Based NSTableView - Stack OverifjerNo ratings yet

- 100 Common Errors in English PDFDocument68 pages100 Common Errors in English PDFKarlitoz Redes85% (20)

- Listening and Reading: Figure D: WIDA Performance Definitions Grades K-12Document2 pagesListening and Reading: Figure D: WIDA Performance Definitions Grades K-12plume1978No ratings yet

- LP Y3 Being HealthyDocument13 pagesLP Y3 Being HealthyNur Suhada Jannah Mohd RaffaliNo ratings yet

- Daily lesson plans for English LanguageDocument10 pagesDaily lesson plans for English LanguageFnatashaaNo ratings yet

- Actividad 3 Apropiación 6Document7 pagesActividad 3 Apropiación 6Cristian Camilo Holguin CastañedaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of English Language For Career Opportunities in The Asean PDFDocument7 pagesThe Importance of English Language For Career Opportunities in The Asean PDFGlobal Research and Development Services100% (3)

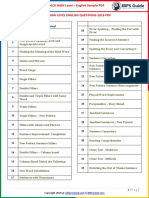

- Crack High Level - English Language Questions 2019 - Sample PDFDocument12 pagesCrack High Level - English Language Questions 2019 - Sample PDFArun KumarNo ratings yet

- GermanDocument310 pagesGermanMuhamed AgicNo ratings yet

- Have A Look Inside Myfarog1Document4 pagesHave A Look Inside Myfarog1valiataNo ratings yet