Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Due Process Digests

Uploaded by

Neil Owen DeonaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Due Process Digests

Uploaded by

Neil Owen DeonaCopyright:

Available Formats

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

Mayor Bayani Alonte vs Judge Maximo Savellano, NBI & People of the Philippines Due Process in Criminal Proceedings Waiver of Right to Due Process FACTS: Alonte was accused of raping JuvieLyn Punongbayan with accomplice Buenaventura Concepcion. It was alleged that Concepcion befriended Juvie and had later lured her into Alonetes house who was then the mayor of Bian, Laguna. The case was brought before RTC Bian. The counsel and the prosecutor later moved for a change of venue due to alleged intimidation. While the change of venue was pending, Juvie executed an affidavit of desistance. The prosecutor continued on with the case and the change of venue was done notwithstanding opposition from Alonte. The case was raffled to the Manila RTC under J Savellano. Savellano later found probable cause and had ordered the arrest of Alonte and Concepcion. Thereafter, the prosecution presented Juvie and had attested the voluntariness of her desistance the same being due to media pressure and that they would rather establish new life elsewhere. Case was then submitted for decision and Savellano sentenced both accused to reclusion perpetua. Savellano commented that Alonte waived his right to due process when he did not cross examine Juvie when clarificatory questions were raised about the details of the rape and on the voluntariness of her desistance. ISSUE: Whether or not Alonte has been denied criminal due process. HELD: The SC ruled that Savellano should inhibit himself from further deciding on the case due to animosity between him and the parties. There is no showing that Alonte waived his right. The standard of waiver requires that it not only must be voluntary, but must be knowing, intelligent, and done with sufficient awareness of the relevant circumstances and likely consequences. Mere silence of the holder of the right should not be so construed as a waiver of right, and the courts must indulge every reasonable presumption against waiver. Savellano has not shown impartiality by repeatedly not acting on numerous petitions filed by Alonte. The case is remanded to the lower court for retrial and the decision earlier promulgated is nullified. NOTES: Due process in criminal proceedings (a) that the court or tribunal trying the case is properly clothed with judicial power to hear and determine the matter before it; (b) that jurisdiction is lawfully acquired by it over the person of the accused; (c) that the accused is opportunity to be heard; and given an

(d) that judgment is rendered only upon lawful hearing. Section 3, Rule 119, of the Rules of Court Sec. 3. Order of trial. The trial shall proceed in the following order: (a) The prosecution shall present evidence to prove the charge and, in the proper case, the civil liability. (b) The accused may present evidence to prove his defense, and damages, if any, arising from the issuance of any provisional remedy in the case. (c) The parties may then respectively present rebutting evidence only, unless the court, in furtherance of justice, permits them to present additional evidence bearing upon the main issue. (d) Upon admission of the evidence, the case shall be deemed submitted for decision unless the court directs the parties to argue orally or to submit memoranda. (e) However, when the accused admits the act or omission charged in the complaint or information but interposes a

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

lawful defense, the order of trial may be modified accordingly. Aniag vs. Commission on Elections [GR 104961, 7 October 1994] En Banc, Bellosillo (J): 6 concur, 3 on leave Facts: In preparation for the synchronized national and local elections scheduled on 11 May 1992, the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) issued on 11 December 1991 Resolution 2323 (Gun Ban), promulgating rules and regulations on bearing, carrying and transporting of firearms or other deadly weapons, on security personnel or bodyguards, on bearing arms by members of security agencies or police organizations, and organization or maintenance of reaction forces during the election period. Subsequently, on 26 December 1991 COMELEC issued Resolution 2327 providing for the summary disqualification of candidates engaged in gunrunning, using and transporting of firearms, organizing special strike forces, and establishing spot checkpoints. On 10 January 1992, pursuant to the Gun Ban, Mr. Serapio P. Taccad, Sergeant-at-Arms, House of Representatives, wrote Congressman Francisc B. Aniag Jr., who was then Congressman of the 1st District of Bulacan requesting the return of the 2 firearms issued to him by the House of Representatives. Upon being advised of the request on 13 January 1992 by his staff, Aniag immediately instructed his driver, Ernesto Arellano, to pick up the firearms from his house at Valle Verde and return them to Congress. Meanwhile, at about 5:00 p,.m. of the same day, the Philippine National Police (PNP) headed by Senior Superintendent Danilo Cordero set up a checkpoint outside the Batasan Complex some 20 meters away from its entrance. About 30 minutes later, the policemen manning the outpost flagged down the car driven by Arellano as it approached the checkpoint. They searched the car and found the firearms neatly packed in their gun cases and placed in a bag in the trunk of the car. Arellano was then apprehended and detained. He explained that he was ordered by Aniag to get the firearms from the house and return them to Sergeant-at Arms Taccad of the House of Representatives. Thereafter, the police referred Arellanos case to the Office of the City Prosecutor for inquest. The referral did not include Aniag as among those charged with an election offense. On 15 January 1992, the City Prosecutor ordered the release of Arellano after finding the latters sworn explanation meritorious. On 28 January 1992, the City Prosecutor invited Aniag to shed light on the circumstances mentioned in Arellanos sworn explanation. Aniag not only appeared at the preliminary investigation to confirm Arellanos statement but also wrote the City Prosecutor urging him to exonerate Arellano. He explained that Arellano did not violate the firearms ban as he in fact was complying with it when apprehended by returning the firearms to Congress; and, that he was Aniags driver, not a security officer nor a bodyguard. On 6 March 1992, the Office of the City Prosecutor issued a resolution which, among other matters, recommended that the case against Arellano be dismissed and that the unofficial charge against Aniag be also dismissed. Nevertheless, on 6 April 1992, upon recommendation of its Law Department, COMELEC issued Resolution 92-0829 directing the filing of information against Aniag and Arellano for violation of Sec. 261, par. (q), of BP 881 otherwise known as the Omnibus Election Code, in relation to Sec. 32 of RA 7166; and Aniag to show cause why he should not be disqualified from running for an elective position, pursuant to COMELEC Resolution 2327, in relation to Secs. 32, 33 and 35 of RA 7166, and Sec. 52, par. (c), of BP 881. On 13 April 1992, Aniag moved for reconsideration and to hold in abeyance the administrative proceedings as well as the filing of the information in court. On 23 April 1992, the COMELEC denied Aniags motion for reconsideration. Aniag filed a petition for

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

declaratory relief, certiorari prohibition against the COMELEC. and By virtue of R.A No. 5514, philcomsat was granted a franchise to establish, construct, maintain and operate in the Philippines, at such places the grantee may select, station or stations and or associated equipment andinternational satellite communications. under this franchise, it was likewise granted the authority to "construct and operate such ground facilities as needed to deliver telecommunications Services from the communications satellite system and the ground terminals. The satellite service thus provided by petitioner enable international carriers to serve the public with indespensible communications service Under sec. 5 of RA 5514, petitioner was exempt from the jurisdiction of the then Public Service commission. Now respondent NTC Pursuant EO 196 petitioner was placed under the jurisdiction and control and regulation of the respondent NTC Respondent NTC ordered the petitoner to apply for the requisite certificate of public convenience and necessity covering its facilities and the services it renders, as well as the corresponding authority to charge rates September 9, 1987, pending hearing, petitioner filed with the NTC an application to continue operating andmaintaining its facilities including a provisional authorityto continue to provide the services and the charges it wasthen charging September 16, 1988 the petitioner was granted a provisional authority and was valid for 6 months, when the provisional authority expired, it was extended for another6 months. However the NTC directed the petitioner to charge modified reduced

Issue: Whether the search of Aniags car that yielded the firarms which were to be returned to the House of Representatives within the purview of the exception as to the search of moving vehicles. Held: As a rule, a valid search must be authorized by a search warrant duly issued by an appropriate authority. However, this is not absolute. Aside from a search incident to a lawful arrest, a warrantless search had been upheld in cases of moving vehicles and the seizure of evidence in plain view, as well as the search conducted at police or military checkpoints which we declared are not illegal per se, and stressed that the warrantless search is not violative of the Constitution for as long as the vehicle is neither searched nor its occupants subjected to a body search, and the inspection of the vehicle is merely limited to a visual search. As there was no evidence to show that the policemen were impelled to do so because of a confidential report leading them to reasonably believe that certain motorists matching the description furnished by their informant were engaged in gunrunning, transporting firearms or in organizing special strike forces. Nor was there any indication from the package or behavior of Arellano that could have triggered the suspicion of the policemen. Absent such justifying circumstances specifically pointing to the culpability of Aniag and Arellano, the search could not be valid. The action then of the policemen unreasonably intruded into Aniags privacy and the security of his property, in violation of Sec. 2, Art. III, of the Constitution. Consequently, the firearms obtained in violation of Aniags right against warrantless search cannot be admitted for any purpose in any proceeding. PHILCOMSAT VS ANIAG. FACTS:

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

rates through a reduction of 15% on the authorized rates Issues: 1. WON EO 546 and EO 196 are unconstitutional on the ground that the same do not fix a standard for the excercise of the power therein conferred? NO 2. WON the questioned order violates Due process because it was issued without notice to petitioner and without the benefit of a hearing? YES 3. WON the rate reduction is confiscatory in that its implementation would virtually result in a cessation of its opeartions and eventual closure of business? YES Held: a. Fundamental is the rule that delegation of legislative power may be sustained only upon the ground that some standard for its exercise is provided and that the legislature in making the delegation has prescribed manner of the exercise of the delegated power. Therefore, when the administrative agency concerned, respondent NTC in this case, establishes a rarte, its act must be both nonconfiscatory and must have been established in the manner prescribed by the legislature; otherwise , in the absence of a fixed standard, the delegation of power becomes unconstitutional. In case of a delegation ofrate-fixing power, the only standard which the legislature is required to prescribe for the guidance of the administrative authority is that the rate be reasonable and just . However, it has been held that even in the absence of an express requirement as to reasonableness, this standard may be implied. b) under Sec. 15 EO 546 and Sec. 16 thereof, Respondent NTC, in the exercise of its rate-fixing power, is limited by the requirements of public safety, public interest, reasonable feasibility and reasonable rates, which conjointly more than satisfy the requirements of a valid delegation of legislative power. 2.a)The function involved in the rate fixing power of the NTC is adjudicatory and hence quasi-judicial, not quasi legislative; thus hearings are necessary and the abscence thereof results in the violation of due process. b)The Central Bank of the Philippines vs. Cloribal " In so far sa generalization is possible in view of the great variety of administrative proceedings, it may be stated as a general rule that the notice and hearing are not essential to the validity of administrative action where the administrative body acts in the excercise of executive, administrative, or legislative functions; but where public adminitrative body acts in a judicial or quasi-judicial matter, and its acts ar eparticular and immediate rather than general and prospective, the person whos rights or property may be affected by the action is entitiled to notice and hearing" c)Even if respondents insist that notice of hearing are not necessary since the assailed order is merely incidental to the entire proceedings and therefore temporary in nature, it is still mot exempt from the statutory procedural requirements of notice and hearing as well as the requirement o reasonableness. d.) it is thus clear that with regard to rate-fixing, respondent has no authority to make such order without first giving petitioner a hearing, whether the order the be temporary or permanent, and it is immaterial wheter the same is made upon a complaint, a summary investigation, or upon the comissions own motion. 3. a.) What the petitioner has is a grant or privilege granted by the State and may revoke it at will there is no question in that, however such grant cannot be

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

unilaterally revoked absent a showing that the termination of the opeartion of said utility is required by common good. The rule is that the power of the State to regulate the conduct and business of public utilities is limited by the consideration that it is not the owner of the property of the utility, or clothed with the general power of management incident to ownership, since the private right of ownership to such property remains and is not to be destroyed by the regulatory power. The power to regulate is not the power to destroy useful and harmless enterprises, but is the power to protect, foster, promote, preserve, and control with due regard for the interest, first and foremost, of the public, then of the utility and its patrons. any regulation, therefore, which operates as an effective confiscation of private property or constitutes an arbitrary or unreasonable infringerement of property rights is void, because it is repugnant to the constitutional guaranties of due process and equal protection of the laws. b.)A cursory persual of the assailed order reveals that the rate reduction is solely and primarily based on the initial evaluation made on the financial statements of petitioner, contrary to respondent NTC's allegation that it has several other sources. Further more, it did not as much as make an attempt to elaborate on how it arrived at the prescribed rates. It just perfunctorily declared that based on the financial statements, there is merit for a ratereduction without any elucidation on what implifications and conclutions were necessariy inferred by it from said staements. Nor did it deign to explain how the datareflected in the financial statements influenced its decision to impose rate reduction. c.) The challenged order, particularly on the rates provided therein, being violative of the due process clause is void and should be nullified. Ang Tibay vs Industrial Relations Court of

Due Process Admin Bodies CIR FACTS: Teodoro Toribio owns and operates Ang Tibay a leather company which supplies the Philippine Army. Due to alleged shortage of leather, Toribio caused the lay off of members of National Labor Union Inc. NLU averred that Toribios act is not valid as it is not within the CBA. That there are two labor unions in Ang Tibay; NLU and National Workers Brotherhood. That NWB is dominated by Toribio hence he favors it over NLU. That NLU wishes for a new trial as they were able to come up with new evidence/documents that they were not able to obtain before as they were inaccessible and they were not able to present it before in the CIR. ISSUE: Whether or not there has been a due process of law. HELD: The SC ruled that there should be a new trial in favor of NLU. The SC ruled that all administrative bodies cannot ignore or disregard the fundamental and essential requirements of due process. They are; (1) The right to a hearing which includes the right of the party interested or affected to present his own case and submit evidence in support thereof. (2) Not only must the party be given an opportunity to present his case and to adduce evidence tending to establish the rights which he asserts but the tribunal must consider the evidence presented. (3) While the duty to deliberate does not impose the obligation to decide right, it does imply a necessity which cannot be disregarded, namely, that of having

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

something to support its decision. A decision with absolutely nothing to support it is a nullity, a place when directly attached. (4) Not only must there be some evidence to support a finding or conclusion but the evidence must be substantial. Substantial evidence is more than a mere scintilla It means such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion. (5) The decision must be rendered on the evidence presented at the hearing, or at least contained in the record and disclosed to the parties affected. (6) The Court of Industrial Relations or any of its judges, therefore, must act on its or his own independent consideration of the law and facts of the controversy, and not simply accept the views of a subordinate in arriving at a decision. (7) The Court of Industrial Relations should, in all controversial questions, render its decision in such a manner that the parties to the proceeding can know the vario issues involved, and the reasons for the decisions rendered. The performance of this duty is inseparable from the authority conferred upon it. ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY VS. HON. JUDGE IGNACIO CAPULONG [222 SCRA 644; G.R. 99327; 27 MAY 1993] Facts: Leonardo H. Villa, a first year law student of Petitioner University, died of serious physical injuries at Chinese General Hospital after the initiation rites of Aquila Legis. Bienvenido Marquez was also hospitalized at the Capitol Medical Center for acute renal failure occasioned by the serious physical injuries inflicted upon him on the same occasion. Petitioner Dean Cynthia del Castillo created a Joint Administration-Faculty-Student Investigating Committee which was tasked to investigate and submit a report within 72 hours on the circumstances surrounding the death of Lennie Villa. Said notice also required respondent students to submit their written statements within twenty-four (24) hours from receipt. Although respondent students received a copy of the written notice, they failed to file a reply. In the meantime, they were placed on preventive suspension. The Joint Administration-Faculty-Student Investigating Committee, after receiving the written statements and hearing the testimonies of several witness, found a prima facie case against respondent students for violation of Rule 3 of the Law School Catalogue entitled "Discipline." Respondent students were then required to file their written answers to the formal charge. Petitioner Dean created a Disciplinary Board to hear the charges against respondent students. The Board found respondent students guilty of violating Rule No. 3 of the Ateneo Law School Rules on Discipline which prohibits participation in hazing activities. However, in view of the lack of unanimity among the members of the Board on the penalty of dismissal, the Board left the imposition of the penalty to the University Administration. Accordingly, Fr. Bernas imposed the penalty of dismissal on all respondent students. Respondent students filed with RTC Makati a TRO since they are currently enrolled. This was granted. A TRO was also issued enjoining petitioners from dismissing the respondents. A day after the expiration of the temporary restraining order, Dean del Castillo created a Special Board to investigate the charges of hazing against respondent students Abas and Mendoza. This was requested to be stricken out by the respondents and argued that the creation of the Special Board was totally unrelated to the original petition which alleged lack of due process. This was granted and reinstatement of the students was ordered. Issue: Was there denial of due process against the respondent

Constitutional Law II: Due Process

students. Held: There was no denial of due process, more particularly procedural due process. Dean of the Ateneo Law School, notified and required respondent students to submit their written statement on the incident. Instead of filing a reply, respondent students requested through their counsel, copies of the charges. The nature and cause of the accusation were adequately spelled out in petitioners' notices. Present is the twin elements of notice and hearing. Respondent students argue that petitioners are not in a position to file the instant petition under Rule 65 considering that they failed to file a motion for reconsideration first before the trial court, thereby by passing the latter and the Court of Appeals. It is accepted legal doctrine that an exception to the doctrine of exhaustion of remedies is when the case involves a question of law, as in this case, where the issue is whether or not respondent students have been afforded procedural due process prior to their dismissal from Petitioner University. Minimum standards to be satisfied in the imposition of disciplinary sanctions in academic institutions, such as petitioner university herein, thus: (1) the students must be informed in writing of the nature and cause of any accusation against them; (2) that they shall have the right to answer the charges against them with the assistance of counsel, if desired: (3) they shall be informed of the evidence against them (4) they shall have the right to adduce evidence in their own behalf; and (5) the evidence must be duly considered by the investigating committee or official designated by the school authorities to hear and decide the case.

You might also like

- Memorandum Points & AuthoritiesDocument33 pagesMemorandum Points & AuthoritiesOdzer Chenma100% (8)

- Compiled Cases - INCOMPLETEDocument105 pagesCompiled Cases - INCOMPLETEEduard RiparipNo ratings yet

- 3.2. City of Manila Vs Chinese CemeteryDocument1 page3.2. City of Manila Vs Chinese CemeteryRandy SiosonNo ratings yet

- HLURB Laws and ProceduresDocument25 pagesHLURB Laws and ProceduresNabby Mendoza50% (4)

- Zaal v. State 326 MDDocument17 pagesZaal v. State 326 MDThalia SandersNo ratings yet

- 2020 Up Boc Legal Ethics ReviewerDocument133 pages2020 Up Boc Legal Ethics ReviewerCastillo Anunciacion Isabel100% (1)

- Tax DoctrinesDocument67 pagesTax DoctrinesMinang Esposito VillamorNo ratings yet

- People vs. PinedaDocument2 pagesPeople vs. PinedaFranklin RichardsNo ratings yet

- 7 Casanova Vs Hors DigestDocument1 page7 Casanova Vs Hors DigestAljay LabugaNo ratings yet

- Positivist SchoolDocument12 pagesPositivist SchoolLeah MoscareNo ratings yet

- Legal MethodDocument11 pagesLegal Methodvanshikakataria554No ratings yet

- Manotoc Vs Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesManotoc Vs Court of AppealsGlenn Robin Fedillaga100% (1)

- A03 S12 06 People vs. Loveria.Document1 pageA03 S12 06 People vs. Loveria.PaulRuizNo ratings yet

- Salumbides vs. Office of OmbudsmanDocument6 pagesSalumbides vs. Office of OmbudsmanVan Dicang100% (1)

- Tejano V OmbudsmanDocument3 pagesTejano V OmbudsmanAibel Ugay100% (1)

- Transportation LawDocument150 pagesTransportation Lawjum712100% (3)

- People v. Macam, G.R. No. 91011-12, Nov. 24, 1994Document2 pagesPeople v. Macam, G.R. No. 91011-12, Nov. 24, 1994Ja RuNo ratings yet

- CRMD and SECDocument3 pagesCRMD and SECRaymart Salamida100% (1)

- Echegaray vs. Secretary of Justice: Lethal Injection RulingDocument4 pagesEchegaray vs. Secretary of Justice: Lethal Injection RulingMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNo ratings yet

- 307 Silverio Vs CA Case DigestDocument1 page307 Silverio Vs CA Case DigestPatrick Rorey Navarro IcasiamNo ratings yet

- Insurance Memoaid 1Document42 pagesInsurance Memoaid 1washburnx20No ratings yet

- Us V BustosDocument4 pagesUs V BustosAnsis Villalon PornillosNo ratings yet

- Social Weather Stations V COMECLECDocument3 pagesSocial Weather Stations V COMECLECsabethaNo ratings yet

- Eminent Domain R V - T Issue:: Epublic S AgleDocument9 pagesEminent Domain R V - T Issue:: Epublic S AgleLorelei B RecuencoNo ratings yet

- PASEI Vs Drilon Liberty of Abode Digest AdvinculaDocument2 pagesPASEI Vs Drilon Liberty of Abode Digest AdvinculaAbby PerezNo ratings yet

- Sy Et Al., vs. Fairland Knitcraft Co IncDocument5 pagesSy Et Al., vs. Fairland Knitcraft Co IncAnonymous zbdOox11No ratings yet

- Quinagoran vs Heirs of Juan de la CruzDocument2 pagesQuinagoran vs Heirs of Juan de la Cruzmonet_antonioNo ratings yet

- Ho Wai Pang Vs People of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesHo Wai Pang Vs People of The PhilippinesLae IsabelleNo ratings yet

- Non-Impairment of Contracts Clause in Ganzon vs InsertoDocument1 pageNon-Impairment of Contracts Clause in Ganzon vs InsertoLily EnchantressNo ratings yet

- Deed of Adjudication With Absolute SaleDocument2 pagesDeed of Adjudication With Absolute SaleNeil Owen Deona89% (9)

- People v. CarandangDocument2 pagesPeople v. CarandangBia FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Right to Counsel in Police Line-UpsDocument5 pagesRight to Counsel in Police Line-UpsJia FriasNo ratings yet

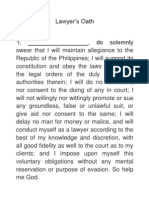

- Lawyer's OathDocument1 pageLawyer's OathKukoy PaktoyNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Case DigestsDocument30 pagesBill of Rights Case DigestsNeil Owen Deona100% (2)

- People VS QuitlongDocument1 pagePeople VS QuitlongJenNo ratings yet

- SC reviews death penalty cases even if convict escapesDocument2 pagesSC reviews death penalty cases even if convict escapesKenny EspiNo ratings yet

- (Consti 2 DIGEST) 113 - Ople Vs TorresDocument11 pages(Consti 2 DIGEST) 113 - Ople Vs TorresCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- A9 Leave Division, OAS-OCA V HeusdensDocument17 pagesA9 Leave Division, OAS-OCA V HeusdensJenNo ratings yet

- Padua vs. ErictaDocument2 pagesPadua vs. ErictaAnna Liza FanoNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Vda de Castellvi DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic v. Vda de Castellvi DigestAlthea M. SuerteNo ratings yet

- BILL OF RIGHTS Sections 1 5Document38 pagesBILL OF RIGHTS Sections 1 5euniNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations I. COLLECTIVE BARGAINING (Arts. 227-277)Document26 pagesLabor Relations I. COLLECTIVE BARGAINING (Arts. 227-277)Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Delos Santos v. MallareDocument2 pagesDelos Santos v. MallareloricaloNo ratings yet

- 74 - Digest - Lozano V Martinez - G.R. No. L-63419 - 18 December 1986Document2 pages74 - Digest - Lozano V Martinez - G.R. No. L-63419 - 18 December 1986Kenneth TapiaNo ratings yet

- Transpo Digest PoolDocument96 pagesTranspo Digest PoolNeil Owen Deona100% (3)

- Digested Case-Eminent Domain - 1Document26 pagesDigested Case-Eminent Domain - 1Jay-r Del PilarNo ratings yet

- Solidon V Macalalad M-ViDocument2 pagesSolidon V Macalalad M-ViJeanella Pimentel CarasNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law2 Ayala de Roxas Vs City of Manila January 30, 2020 Case DigestDocument5 pagesConstitutional Law2 Ayala de Roxas Vs City of Manila January 30, 2020 Case DigestBrenda de la GenteNo ratings yet

- Philippine Communications Satellite Corporation v. Jose Luis A. Alcuaz (G.r. No. 84818. December 18, 1989)Document2 pagesPhilippine Communications Satellite Corporation v. Jose Luis A. Alcuaz (G.r. No. 84818. December 18, 1989)Ei BinNo ratings yet

- Court Rules No Violation of Right to Public TrialDocument6 pagesCourt Rules No Violation of Right to Public TrialOdette Jumaoas100% (2)

- Custodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnDocument5 pagesCustodial Investigation Section 12. (1) Any Person Under Investigation For The Commission of AnBananaNo ratings yet

- Garcia V ManuelDocument2 pagesGarcia V ManuelCedrickNo ratings yet

- Paulin vs. GimenezDocument1 pagePaulin vs. GimenezDana Denisse RicaplazaNo ratings yet

- 222-Ganzon Vs Inserto 123 SCRA 713Document2 pages222-Ganzon Vs Inserto 123 SCRA 713Arlen Rojas0% (2)

- Philippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Document3 pagesPhilippine Refining Company Worker's Union vs. Philippine Refining Co. (G.R. No. L-1668, March 29, 1948)Marienyl Joan Lopez VergaraNo ratings yet

- Revised Penal Code Articles 1 - 20Document5 pagesRevised Penal Code Articles 1 - 20LouieNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Iron Steel Vs CADocument2 pagesCase Digest Iron Steel Vs CAEbbe Dy100% (1)

- Sta. Maria vs. TuazonDocument15 pagesSta. Maria vs. Tuazonchan.aNo ratings yet

- Narvasa Rules on Enrile Habeas Corpus PleaDocument2 pagesNarvasa Rules on Enrile Habeas Corpus PleaRuth DulatasNo ratings yet

- United States v. Felipe Bustos Et Al. challenges right to criticize judgesDocument3 pagesUnited States v. Felipe Bustos Et Al. challenges right to criticize judgesSamuel John CahimatNo ratings yet

- Namil Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesNamil Vs ComelecOceane AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Flores vs. People (G.R. No. L-25769, December 10, 1974) FERNANDO, J.: FactsDocument20 pagesFlores vs. People (G.R. No. L-25769, December 10, 1974) FERNANDO, J.: FactsRegine LangrioNo ratings yet

- 05.02-Ducat Jr. v. Villalon Jr.Document7 pages05.02-Ducat Jr. v. Villalon Jr.Odette Jumaoas100% (1)

- Director of Religoius Affairs Vs Baloyot A.C. No. L-1117Document3 pagesDirector of Religoius Affairs Vs Baloyot A.C. No. L-1117Jonjon BeeNo ratings yet

- Arkoncel v. Court of First Instance of Basilan City, G.R. No. L-27204, August 29, 1975Document5 pagesArkoncel v. Court of First Instance of Basilan City, G.R. No. L-27204, August 29, 1975JasenNo ratings yet

- Case #4Document9 pagesCase #4Mariell PahinagNo ratings yet

- People vs. PinlacDocument5 pagesPeople vs. PinlacJason CruzNo ratings yet

- Calalang Vs WilliamsDocument3 pagesCalalang Vs Williamsmichael jan de celisNo ratings yet

- Sec. 17 DigestDocument9 pagesSec. 17 DigestVen John J. LluzNo ratings yet

- Mayor lacks power to deport womenDocument1 pageMayor lacks power to deport womenWhere Did Macky GallegoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-56450 - Ganzon vs. InsertoDocument5 pagesG.R. No. L-56450 - Ganzon vs. InsertoseanNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. ROMEO G. JALOSJOSDocument2 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. ROMEO G. JALOSJOSJoel LopezNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Feliciano vs. LBPDocument6 pagesHeirs of Feliciano vs. LBPMerNo ratings yet

- Poli Case Digest (Privacy of Communications and Correspondence)Document4 pagesPoli Case Digest (Privacy of Communications and Correspondence)Chi OdanraNo ratings yet

- DelicadezaDocument7 pagesDelicadezaromeo n bartolomeNo ratings yet

- Due Process DigestsDocument6 pagesDue Process DigestsAlthea EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Aniag vs. Comission On ElectionDocument18 pagesAniag vs. Comission On ElectionLyka Lim PascuaNo ratings yet

- Aniag v. ComelecDocument13 pagesAniag v. ComelecjrNo ratings yet

- Aguilar Vs O'PallickDocument9 pagesAguilar Vs O'PallickNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- 4e Civ RevDocument75 pages4e Civ RevNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Amla 15-007-37 9-30-22Document1 pageAmla 15-007-37 9-30-22Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Bagong Kapisanan Vs DolotDocument15 pagesBagong Kapisanan Vs DolotNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Suspension of PaymentDocument8 pagesSuspension of PaymentNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Transpo Chapter 8 - 11Document48 pagesTranspo Chapter 8 - 11Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Complaint in Intervention PDFDocument10 pagesComplaint in Intervention PDFNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Torts Set 3 - AnnotatedDocument18 pagesTorts Set 3 - AnnotatedNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Complaint in Intervention PDFDocument10 pagesComplaint in Intervention PDFNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Ra 10361Document13 pagesRa 10361Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Petition CyberlawDocument38 pagesPetition CyberlawMich AngelesNo ratings yet

- Republic Act 8282 - Social Security Law 1997 - AnnotatedDocument29 pagesRepublic Act 8282 - Social Security Law 1997 - AnnotatedNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Wills Set 1 Cases 12-21Document47 pagesWills Set 1 Cases 12-21Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- 001Document17 pages001Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Beda NotesDocument27 pagesBeda NotesMarien Gonzales LopezNo ratings yet

- BankingDocument48 pagesBankingjaine0305No ratings yet

- Corpo 7th SetDocument56 pagesCorpo 7th SetNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court rules special assessment invalid due to union's failure to comply with legal requirementsDocument29 pagesSupreme Court rules special assessment invalid due to union's failure to comply with legal requirementsNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Corpo 1st SetDocument88 pagesCorpo 1st SetNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Labor Relatlions Azucena Voli I FinalsDocument52 pagesLabor Relatlions Azucena Voli I FinalsNeil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- 1582 1599Document4 pages1582 1599Neil Owen DeonaNo ratings yet

- Court Documents: Read Atkins' ComplaintDocument11 pagesCourt Documents: Read Atkins' ComplaintThe Jackson SunNo ratings yet

- Section 4C AssignmentDocument10 pagesSection 4C AssignmentDaniel RafidiNo ratings yet

- KILLING AN ANIMAL NOT A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT - Naresh KadyanDocument2 pagesKILLING AN ANIMAL NOT A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT - Naresh KadyanNaresh KadyanNo ratings yet

- Agcopra ExplanationDocument4 pagesAgcopra ExplanationPnp Initao MpsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Santos Jesus Martinez-Torres, United States of America v. Luis Alfredo Martinez-Torres, United States of America v. Epifanio Martinez-Torres, A/K/A "Fanny,", 912 F.2d 1552, 1st Cir. (1990)Document17 pagesUnited States v. Santos Jesus Martinez-Torres, United States of America v. Luis Alfredo Martinez-Torres, United States of America v. Epifanio Martinez-Torres, A/K/A "Fanny,", 912 F.2d 1552, 1st Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- SC strikes down BCI's 45-year age limit for lawyer enrollmentDocument18 pagesSC strikes down BCI's 45-year age limit for lawyer enrollmentArun Vignesh67% (3)

- Lecture Notes - Inchoate CrimesDocument21 pagesLecture Notes - Inchoate CrimesAsha YadavNo ratings yet

- Larranaga 2004 DecisionDocument34 pagesLarranaga 2004 DecisionMarivic Samonte ViluanNo ratings yet

- R V Milne (Mark James) (2013) EWCA Crim 1999Document4 pagesR V Milne (Mark James) (2013) EWCA Crim 1999Thom Dyke100% (1)

- CLAT Study Material Law of CrimeDocument29 pagesCLAT Study Material Law of CrimeYoga LoverNo ratings yet

- Perubahan Konstitusi Dan Reformasi Ketatanegaraan IndonesiaDocument8 pagesPerubahan Konstitusi Dan Reformasi Ketatanegaraan IndonesiaEndah RyaniNo ratings yet

- Philippines Supreme Court upholds dismissal of cook caught stealing squidDocument42 pagesPhilippines Supreme Court upholds dismissal of cook caught stealing squidDreiBaduaNo ratings yet

- Brown v. Lantz, Et Al. - Document No. 4Document1 pageBrown v. Lantz, Et Al. - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Cabales V.caDocument7 pagesCabales V.caSimeon SuanNo ratings yet

- GABRIEL ABAD V RTC MLA G.R. No. L-65505 October 12, 1987Document2 pagesGABRIEL ABAD V RTC MLA G.R. No. L-65505 October 12, 1987JoanNo ratings yet

- Posco ActDocument5 pagesPosco ActSabya Sachee RaiNo ratings yet

- Civil Service Commission orders reinstatement of provincial employeesDocument8 pagesCivil Service Commission orders reinstatement of provincial employeesRonn PagcoNo ratings yet

- 10 Social Security Commission Vs Rizal PoultyDocument10 pages10 Social Security Commission Vs Rizal Poultygenel marquezNo ratings yet

- Armstrong v. Exceptional Child Center, Inc. (2015)Document30 pagesArmstrong v. Exceptional Child Center, Inc. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Allied Banking Vs QCDocument8 pagesAllied Banking Vs QCJAMNo ratings yet