Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Are Folksonomies

Uploaded by

api-88763172Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Are Folksonomies

Uploaded by

api-88763172Copyright:

Available Formats

Melanie Wilson LIS 745 Summer 2010 Topic Paper July 7, 2010

Tagging: The Next Step for Libraries to Take for Information Access?

Two major areas of concern for librarians today are providing access to information, and increasing patron usage of library resources to help ensure the futures of their institutions. The explosion of information shared on the internet and other electronic resources has created new challenges in organizing and disseminating information. It has also changed the publics expectations of access and retrieval, particularly as Web 2.0 allows them to move from being just consumers of information to prosumers, both producers and consumers (Stock 2007, 97). Increasingly popular, folksonomies may be just what libraries need to embrace to manage this rapidly changing digital environment. But what are the challenges and benefits to integrating them with current systems of organization and retrieval? The term folksonomy is a combination of the terms folks and taxonomy, and commonly refers to a collection of descriptive tags assigned to a digital object by users. The term however is a bit of a misnomer. Taxonomies are hierarchical, controlled vocabularies that establish parent-child relationships between terms (Visser 2010, 35). These controlled vocabularies adhere to a clearly articulated set of complex rules. Folksonomies such as tagging, however, are not hierarchical but flat, and do not have a controlled vocabulary. Unlike controlled vocabularies such as the Library of Congress subject headings, folksonomies are not classification schemes, but rather a way of categorizing things (Sun 2008, 120). By their very folks-y nature, the assignment of tags is a democratic process in which any individual may assign any tag they want to any digital object. Subject headings, in contrast, are

assigned by a cataloger, based on his or her own interpretation of the content and authors intent, and following a complex, very specific set of rules government categories and relationships. Folksonomies can be broad, in which many people tag the same object with numerous tags for public use, or they can be narrow, in which one or only a few people tag an object for personal use. The tags in these folksonomies can be either objective or subjective. Objective tags describe the content of an item, and are useful for large numbers of people. Subjective tags on the other hand describe ones reaction to or relationship to an item, and are usually only relevant to the person assigning the tag. While obviously these broad folksonomies consisting of objective tags are more useful for organizing and increasing access to information, there are still some issues with them. Because there are no rules for assigning tags and no quality control, misspellings, singular vs. plural forms, synonyms, etc. can interfere with retrieval. One might not search for the same synonym or the same variation of a word used by the people tagging the items, in which case many resources could be overlooked (Rolla 2009, 81). Perhaps improved search tools could automatically search for synonyms, different spellings, and different forms of the same word, but the majority of sites and catalogs currently using tagging will only retrieve tags exactly as users have entered them. Controlled vocabularies such as Library of Congress subject headings and database thesauri eliminate these possible ambiguities. However, the rules governing controlled vocabulary do not allow for the same variety of analysis of an object that tagging allows. In these hierarchical systems, there are fixed, specific relationships between ideas. However, in reality, there are multiple relationships between these ideas and resources that cannot be classified so rigidly. Folksonomies allow for the expression of a multitude of relationships, aiding in not only discovery of items but also our understanding of them. In most cases, the cataloger also does not actually have time to read the object being cataloged, and instead has to rely on information such as the title, publishers blurb, and table of contents to assign subject headings. The users assigning tags,

however, are familiar with the items being tagged, and may interpret the content of the item differently. These added perspectives can increase the possibilities for retrieval, as well as enhance the catalogers understanding of how people are thinking about things, allowing the controlled vocabulary itself to be improved. Controlled vocabularies also require a buy-in by the user. One must let go of ones own ideas about search terms and their meaning, and subscribe to those of the system, which could interfere with ones ability to properly retrieve the information one is looking for. Using the system properly requires a commitment of time and effort to learn the rules for search terms, and especially in an era of quick and easy (though not always satisfactory) Google searches, this is something many users will be resistant to do, whether consciously or not (Lawson 2009, 580). The ideal approach seems to be using the strengths of both systems in conjunction to create a system that better meets the needs of users, or enhancing existing systems. Peterson reviewed academic libraries and museums that have been experimenting with combining the controlled vocabulary in their catalogs with user-supplied tag. In some cases this not only aids retrieval but also actually adds to the sites content, as in the case with the Minneapolis Institute of Art, where users can create their own galleries and tag and add images to them (Peterson 2008, 3). Some public library catalogs have started to experiment with allowing users to add tags to items in their online catalogs, and giving users the option of making these tags public so that others may use them to discover library materials. Rolla points out that different libraries serve different populations, and therefore user tags will be inherently more appropriate from different libraries and different types of users (2009, 182). While most studies have evaluated the way folksonomies can work in systems geared more towards the general public, such as public library catalogs, tagging could also work in a more specialized system, such as the realm of science publication. Stock proposes that scientific literature could be tagged by

knowledgeable readers and experts, not only contributing to the indexing of the documents, but also allowing for multiple interpretations from different disciplines or different schools of thought. He conceives of this method having an inherent kind of quality control, in which the more scientists tag a document, the more relevance it has for the scientific community, creating another way to evaluate ideas and writers, in addition to citation analysis (Stock 2007, 98-99). He even goes so far as to present an algorithm for relevancy, similar in purpose to Flickrs interestingness algorithm, that would sort scientific articles based on tags and their distribution, indicators of collaboration, recommendations of readers, and so forth (Stock 2007, 100). Studies such as those carried out by Spiteri have discovered that objective tags do tend to correspond closely to NISO guidelines for controlled vocabularies when it comes to types of concepts expressed, use of recognized spelling, and predominance of single terms and nouns. As Lawson points out, librarians can instruct users on best practices for assigning tags for public use, and can also periodically clean up library catalogs by eliminating public subjective tags that are most likely irrelevant to other users (2009, 578, 580). Spiteri also suggests that guidelines can be added to social bookmarking sites instructing users on methods for avoiding ambiguous tags, helping them create tags that will be useful to other users(2007, 22). According to Rolla, catalogs that incorporate folksonomies allow patrons to personalize the librarys website, thereby bolstering a spirit of belonging and also fostering online communities organized around the library (2009, 175). At a time when so many libraries are struggling to prove their relevancy in a digital world, having this kind of user buy-in could only be a benefit. As users feel more invested in their libraries, more involved, and feel more of a sense of ownership to their libraries collections, they will most likely continue to be strong advocates for their libraries and motivated to ensure their libraries futures. This could be particularly useful for members of communities who feel

otherwise alienated and marginalized, or for those active in digital communities who do not currently feel a connection with libraries. Folksonomies do provide challenges to the type of structured and controlled searching that librarians and experienced searches value, but they also provide many benefits that are worth researching and experimenting with. As Lawson states Librarian 2.0 does not shy away from nontraditional cataloging and classification and chooses tagging, tag clouds, folksonomies, and userdriven content descriptions and classifications where appropriate (2009, 574). In an era where the popularity of collaboration and user-generated content is ever-growing, folksonomies and tagging have significant potential for connecting people with what libraries have to offer, helping libraries tailor their collections to meet the needs and desires of these groups, and enhancing our knowledge and understanding that the sharing of information provides.

Works Cited

Lawson, Karen G.. 2009. "Mining Social Tagging Data for Enhanced Subject Access for Readers and Researchers." The Journal of Academic Librarianship 35, no. 6: 574-82. OmniFile Full Text Mega, WilsonWeb (accessed 1 July 2010). Peterson, Elaine. 2008. "Parallel Systems: The Coexistence of Subject Cataloging and Folksonomy." Library Philosophy and Practice 2008: 1-5. OmniFile Full Text Mega, WilsonWeb (accessed 1 July 2010). Peterson, Elaine. 2009. "Patron Preferences for Folksonomy Tags: Research Findings When Both Hierarchical Subject Headings and Folksonomy Tags Are Used." Evidence Based Library and Information Practice 4, no. 1: 53-6. OmniFile Full Text Mega, WilsonWeb (accessed 1 July 2010). Rolla, Peter J. 2009. "User Tags versus Subject Headings: Can User-Supplied Data Improve Subject Access to Library Collections?." Library Resources & Technical Services 53, no. 3: 174-184. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed July 1, 2010). Spiteri, Louise F. 2007. "The Structure and Form of Folksonomy Tags: The Road to the Public Library Catalog." Information Technology & Libraries 26, no. 3: 13-25. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed July 1, 2010). Stock, Wolfgang G. 2007. "Folksonomies and science communication: A mash-up of professional science databases and Web 2.0 services." Information Services & Use 27, no. 3: 97-103. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed July 1, 2010). Sun, Beth DeFrancis. 2008. "Folksonomy and Health Information Access: How can Social Bookmarking Assist Seekers of Online Medical Information?." Journal of Hospital Librarianship 8, no. 1: 119126. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed July 1, 2010). Visser, Marijke A. 2010. "Tagging: An Organization Scheme for the Internet." Information Technology & Libraries 29, no. 1: 34-39. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed July 1, 2010).

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

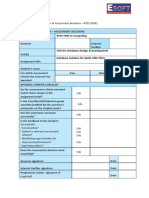

- DatabaseproposalDocument11 pagesDatabaseproposalapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mwilson ReflectionsDocument5 pagesMwilson Reflectionsapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mla Encyclopedia SchizophreniaDocument19 pagesMla Encyclopedia Schizophreniaapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mwilson ResumeDocument2 pagesMwilson Resumeapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Managing Space and User Service Innovations in The Medical LibraryDocument14 pagesManaging Space and User Service Innovations in The Medical Libraryapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mwilson Lis768 ResearchpaperDocument16 pagesMwilson Lis768 Researchpaperapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mwilson FinalDocument15 pagesMwilson Finalapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Library Director Sea Jellies ClearinghouseDocument24 pagesLibrary Director Sea Jellies Clearinghouseapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Melanie Wilsonlis753spring2010finalexcerptDocument2 pagesMelanie Wilsonlis753spring2010finalexcerptapi-88763172No ratings yet

- FinalDocument2 pagesFinalapi-88763172No ratings yet

- A Scholarly Journal With A Global, Multidisciplinary Focus: Schizophrenia: The Social DimensionDocument4 pagesA Scholarly Journal With A Global, Multidisciplinary Focus: Schizophrenia: The Social Dimensionapi-88763172No ratings yet

- The Sabbath VDocument9 pagesThe Sabbath Vapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Mwilson Lis796 3Document4 pagesMwilson Lis796 3api-88763172No ratings yet

- The 20 Library 20 Is 20 Everywhere 20 Handout 1Document4 pagesThe 20 Library 20 Is 20 Everywhere 20 Handout 1api-88763172No ratings yet

- FinalDocument6 pagesFinalapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Biblioburro and FriendsDocument11 pagesBiblioburro and Friendsapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Libraries and Mental Health HandoutDocument2 pagesLibraries and Mental Health Handoutapi-88763172No ratings yet

- The Library Is EverywhereDocument76 pagesThe Library Is Everywhereapi-88763172No ratings yet

- Libraries and Mental Health Issues 2Document6 pagesLibraries and Mental Health Issues 2api-88763172No ratings yet

- Lis 701 Midterm PaperDocument17 pagesLis 701 Midterm Paperapi-88763172No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- M3-Social Media Text AnalyticsDocument19 pagesM3-Social Media Text AnalyticsKHAN SANA PARVEENNo ratings yet

- Best AnswerDocument133 pagesBest AnswerTNT1842No ratings yet

- TCRM10 Contents: Unit 1: Introduction To SAP CRMDocument5 pagesTCRM10 Contents: Unit 1: Introduction To SAP CRMEduardo Eyzaguirre Alberca0% (1)

- The Model View Controller Framework: Jogesh K. MuppalaDocument7 pagesThe Model View Controller Framework: Jogesh K. MuppalavikramNo ratings yet

- Business Partner Concept in SAP S4HANADocument56 pagesBusiness Partner Concept in SAP S4HANAAymen AddouiNo ratings yet

- Database Fundamentals Chapter 3: The Relational Data ModelDocument51 pagesDatabase Fundamentals Chapter 3: The Relational Data ModelYohannes DerejeNo ratings yet

- Joget Mini Case Studies TelecommunicationDocument3 pagesJoget Mini Case Studies TelecommunicationavifirmanNo ratings yet

- Database Solution for Quiet Attic FilmsDocument15 pagesDatabase Solution for Quiet Attic FilmsDPereraNo ratings yet

- Designing an Effective Records Management SystemDocument61 pagesDesigning an Effective Records Management SystemErnieco Jay AhonNo ratings yet

- Donald Norman’s Model ExplainedDocument4 pagesDonald Norman’s Model ExplainedSobia AliNo ratings yet

- 26 - Road AccDocument10 pages26 - Road Accgunda prashanthNo ratings yet

- Comp 675 Human-: Final Exam Fall 1999Document9 pagesComp 675 Human-: Final Exam Fall 1999suryaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Management & BI: Leveraging Data for Strategic DecisionsDocument26 pagesKnowledge Management & BI: Leveraging Data for Strategic DecisionsBehnam ShooshtariNo ratings yet

- International AL Information Technology Unit 4 Candidate Evidence TemplateDocument3 pagesInternational AL Information Technology Unit 4 Candidate Evidence TemplateAx ZxNo ratings yet

- HNAS Storage Pool and HDP Best PracticesDocument29 pagesHNAS Storage Pool and HDP Best PracticesblackburNo ratings yet

- SAP Cybersecurity Comparison Chart v8Document4 pagesSAP Cybersecurity Comparison Chart v8ep2308420% (1)

- Revista Geintec-Gestao Inovacao E Tecnologias: Master Journal ListDocument5 pagesRevista Geintec-Gestao Inovacao E Tecnologias: Master Journal ListPhD Research ProjectsNo ratings yet

- Purpose of Library in SchoolDocument17 pagesPurpose of Library in SchoolshaluNo ratings yet

- MS Access MCQ QuestionsDocument19 pagesMS Access MCQ QuestionsLasith MalingaNo ratings yet

- Om DelvadiaDocument1 pageOm DelvadiavivekparasharNo ratings yet

- Kasus Sia Pert10 Siklus ProduksiDocument100 pagesKasus Sia Pert10 Siklus ProduksiAlda ArtantiNo ratings yet

- DTU Fundamentals of Database Systems ModuleDocument43 pagesDTU Fundamentals of Database Systems ModuleZewoldeNo ratings yet

- Topical Authority Mind MappingDocument1 pageTopical Authority Mind Mappingnimrali2021No ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: TR Requisition NR: 0856417013 Doc. Number: FAC10005-CHI-000-PCS-DTS-0001 Rev: Sheet 18 of 23Document6 pagesSafety Data Sheet: TR Requisition NR: 0856417013 Doc. Number: FAC10005-CHI-000-PCS-DTS-0001 Rev: Sheet 18 of 23Bn BnNo ratings yet

- Microsoft.70 630.logicsmeet.4!6!2012Document28 pagesMicrosoft.70 630.logicsmeet.4!6!2012diffuser911No ratings yet

- AWAD All PDF LecturesDocument569 pagesAWAD All PDF LecturesAmar RiazNo ratings yet

- ECM Solutions in Microsoft Office SharePoint Server 2007Document40 pagesECM Solutions in Microsoft Office SharePoint Server 2007rranchesNo ratings yet

- Autodesk Construction Cloud OverviewDocument1 pageAutodesk Construction Cloud OverviewPierpaolo VergatiNo ratings yet

- Oracle DBA QueriesDocument27 pagesOracle DBA QueriesSajeev K PuthiyedathNo ratings yet

- Data Quality Assessment GuideDocument7 pagesData Quality Assessment GuideNewCovenantChurchNo ratings yet