Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Good Article Legitimate Expectation

Uploaded by

Ng Yih MiinOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Good Article Legitimate Expectation

Uploaded by

Ng Yih MiinCopyright:

Available Formats

From the SelectedWorks of Dharmendra Chatur

February 2011

Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

Contact Author

Start Your Own SelectedWorks Available at: http://works.bepress.com/dchatur/6

Notify Me of New Work

DOCTRINE OF LEGITIMATE EXPECTATIONS

A Comparative and Analytical Study

III Year B.A., LL.B. (Hons.) Dharmendra Chatur 08D6015

VI Semester Administrative Law 2 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

CONTENTS

Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction to the Doctrine ....................................................................................................... 3 Judicial Development of Legitimate Expectations in the United Kingdom .............................. 6 How can a legitimate expectation arise? ................................................................................ 7 Standard of Review for breach of legitimate expectation ...................................................... 8 Judicial Development of Legitimate Expectations in India ....................................................... 9 Concluding Remarks ................................................................................................................ 13 Bibliography ............................................................................................................................ 14 Journal Articles .................................................................................................................... 14 Books and Treatises ............................................................................................................. 15 Caselaw ................................................................................................................................ 15

VI Semester Administrative Law 3 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

INTRODUCTION TO THE DOCTRINE

It cannot be overemphasized that the concept of legitimate expectation has now emerged as an important doctrine. It is stated that it is the latest recruit to a long list of concepts fashioned by the court to review an administrative action.1 It operates in public domain and in appropriate cases constitutes a substantive and enforceable right.2 As a doctrine it takes its place beside such principles as rules of natural justice, rule of law, non-arbitrariness, reasonableness, fairness, promissory estoppel, fiduciary duty and perhaps, proportionality to check the abuse of the exercise of administrative power. The principle at the root of the doctrine is Rule of Law which requires regularity, predictability and certainly the governments dealing with the public.3 An expectation could be based on an express promise, or representation or by established past action or settled conduct. It could be a representation to the individual or generally to a class of persons. Whether an expectation exists is a question of law, but clear statutory words override any expectation, however founded. However as an equity doctrine it is not rigid and operates in areas of manifest injustice. It enforces a certain standard of public morality in all public dealings. However, considerations of public interest would outweigh its application. It would immensely benefit those who are likely to be denied relief on the ground that they have no statutory right to claim relief. Exercise of discretion is an inseparable part of sound administration and, therefore, the State which is itself a creature of the Constitution, cannot shed its limitation at any time in any sphere of State activity. A discretionary power is one which is exercisable by the holder of the power in his discretion or subjective satisfaction. The exercise of discretion must not be arbitrary, fanciful and influenced by extraneous considerations. In matters of discretion the choice must be dictated by public interest and must not be unprincipled or unreasoned. Reasonable and non-arbitrary exercise of discretion is an inbuilt requirement of the law and any unreasonable or arbitrary exercise of it violates Article 14 of the Constitution of India, 1950. The discretion must be exercised reasonably in furtherance of public policy, public

1 2 3

Union of India v. Hindustan Development Corpn., (1993) 3 SCC 499. M.P. Oil Extraction Co. v. State of M.P., (1997) 7 SCC 592. Chanchal Goyal (Dr.) v. State of Rajasthan, (2003) 3 SCC 485.

VI Semester Administrative Law 4 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

good and for public cause. This doctrine of legitimate expectation acts as a deterrent for those in charge of public power from exercising it arbitrarily. It should not be capped, cabined or confined in narrow, pedantic and lexographic approach; rather it should be given broadest of interpretations so as to cover within its purview the dialectics and dynamics of fairness and efficiency. The basic purpose for the same being the expectation in a rule of law society is that holders of public power and authority must be able to publicly justify their action as legally valid and socially wise and just. Under such circumstances, it becomes an inherent right of the public in a democracy to prevent themselves from the abuse of discretion and do not get susceptible to the deadly tentacles of arbitrariness and unreasonableness. As the legitimate expectation doctrine gained acceptance, it was invoked in a wider range of cases, which can be conveniently summarised into four categories: 1. The first was cases in which a person had relied upon a policy or norm of general application but was then subjected to a different policy or norm. 2. The second category, which was a slight variation on the first, included cases in which a policy or norm of general application existed and continued but was not applied to the case at hand. 3. A third category arose when an individual received a promise or representation which was not honoured due to a subsequent change to a policy or norm of general application. 4. A fourth category, which was a variation on the third, arose when an individual received a promise or representation which was subsequently dishonoured, not because there had been a general change in policy, but rather because the decisionmaker had changed its mind in that instance.4 This doctrine has found acceptance not only in the U.K.5 (as this paper will elaborate in the next chapter) where it originated, but also in Australia,6 South Africa,7 Hong Kong,8 Singapore,9 New Zealand,10 Canada11 and as this paper will examine, in India.12

4 5

P P CRAIG, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, 641 (5th ed, 2003).

PAUL CRAIG, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, 646-91 (6th ed, 2008); WILLIAM WADE & CHRISTOPHER FORSYTH, ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, 446-457 (10th ed, 2009); Iain Steele, Substantive Legitimate Expectations: Striking the Right Balance? (2005) 121 LAW QUARTERLY REVIEW 300; Mark Elliott, Legitimate Expectations and the Search for Principle: Reflections on Abdi & Nadarajah [2006] JUDICIAL REVIEW 281; Melanie Roberts, Public Law Representations and Substantive Legitimate Expectations, 64 (1) MODERN LAW REVIEW 112122 (2001), Sales & Steyn, Legitimate Expectations in English Law: An Analysis, (2004) PUBLIC LAW 564653; Robert E. Riggs, Legitimate Expectation and Procedural Fairness in English Law, 36 (3) AM. J. COMP. L. 395 (1988). See

VI Semester Administrative Law 5 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

The aim of this research paper is to make a comparative analytical study of the development of the doctrine of legitimate expectation in England and India. The research materials included both primary and secondary sources. The scope of this paper is limited to only case law of England and India due to paucity of time and space. However, wherever occasioned, relevant case law from different countries have been alluded to. The paper has been divided into three main chapters. The first one is an introduction to the doctrine, the second contains a judicial development of the doctrine in England and the third contains the development of the doctrine in India, mainly cases from the Supreme Court of India.

generally, SCHNBERG, LEGITIMATE EXPECTATIONS IN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW (2000); ROBERT THOMAS, LEGITIMATE EXPECTATIONS AND PROPORTIONALITY IN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW (2000).

6

See, Matthew Groves, Substantial Legitimate Expectations in Australian Administrative Law, 32 (2) MELBOURNE UNIV. L. R. 470 (2008); John Hlophe, Legitimate Expectation and Natural Justice: English Australian and South African Law, 105 S. AFRICAN L. J. 165 (1987); Cameron Stewart, Substantive Unfairness: A New Species of Abuse of Power? 28 Federal Law Review 617 (2000); Cameron Stewart, The Doctrine of Substantive Unfairness and the Review of Substantive Legitimate Expectations in MATTHEW GROVES AND H P LEE (eds), AUSTRALIAN ADMINISTRATIVE LAW: FUNDAMENTALS, PRINCIPLES AND DOCTRINES 280 (2007).

7

Daniel Malan Pretorius, Ten Years After Traub:The Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation in South African Administrative Law, 117 S. AFRICAN L. J. 520 (2000); Geo Quinot, Substantive Legitimate Expectations in South African and European Administrative Law, 5 (1) GERMAN LAW JOURNAL 65 (2004).

8

In Tung v Director of Immigration [2002] 1 HKLRD 561, 600 (Li CJ, Chan and Ribeiro PJJ and Mason NPJ): The doctrine recognizes that, in the absence of any overriding reason of law or policy excluding its operation, situations may arise in which persons may have a legitimate expectation of a substantive outcome or benefit, in which event failing to honour the expectation may, in particular circumstances, result in such unfairness to individuals as to amount to an abuse of power justifying intervention by the court. The circumstances of this case and its use of the legitimate expectation doctrine are explained in Teresa Martin, Hong Kong Right of Abode: Ng Siu Tung & Others v Director of Immigration Constitutional and Human Rights at the Mercy of China, 5 SAN DIEGO INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL 465 (2004). See also, Benny Y T Tai and Kevin K F Yam, The Advent of Substantive Legitimate Expectations in Hong Kong: Two Competing Visions, [2002] PUBLIC LAW 688.

9

Re Siah Mooi Guat, [1988] 2 S.L.R. (R.) 165, H.C.; Borissik Svetlana v. Urban Redevelopment Authority [2009] 4 S.L.R. (R.) 92, H.C.

10 11

See, Chandra v, Minister of Immigration, 1978 (2) NZLR 559, 572.

David Wright, Rethinking The Doctrine Of Legitimate Expectations In Canadian Administrative Law, 35 (1) Osgoode Hall L. J. 139 (1997).

12

See generally, B. C. SARMA, THE LAW OF ULTRA VIRES, 299-312 (Eastern Law House, 2004); JAIN & JAIN, PRINCIPLES OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, 2660-264 (6th ed, 2010). See, Shantimal Jain, Legitimate Expectation-A Confusing Cauldron, The Chartered Accountant, October 2003, 427-9.

VI Semester Administrative Law 6 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

JUDICIAL DEVELOPMENT OF LEGITIMATE EXPECTATIONS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

The Courts in England have been faced with various situations in which they have had to deal with the aspect of legitimate expectations. The developments that the Courts have brought abut have lent a structural stability to the concept. Types of Legitimate Expectations: 13 1. Procedural Legitimate ExpectationDenotes the existence of some process right the applicant claims to possess as a result of behavior by the public body that generates the expectation.14 2. Substantive Legitimate ExpectationRefers to the situation in which the applicant seeks a particular benefit or commodity, such as a welfare benefit or license. The claim to such a benefit will be founded upon governmental action which is said to justify the existence of the relevant expectation.15 Some of the arguments in favor of substantive legitimate expectations are: it creates fairness in public administration,16 reliance and trust in government, principle of equality, upholds rule of law.17 Reasons for protecting legitimate expectations It is required by fairness;18 abuse of power has been considered the root concept justifying the protection of legitimate expectations;19 in European context, legal certainty i.e. the individual ought to be able to plan his or her action on the basis that the expectation will be fulfilled is

13 14 15

CRAIG, supra note 5 at 647. See, R. v. Liverpool Taxi Fleet Association, [1972] 2 QB 299.

Ex. P. Hamble (Offshore) Fisheries Ltd [1995] 2 All. E.R. 714, 724; Hargreaves, [1997] 1 WLR 906. See also, Coughlan, [2001] QB 213.

16 17

Id.

CRAIG, supra note 5 at 651. The Arguments against substantive legitimate expectations is on page 652. One of them is that the existing policy should not be ossified and unduly fettered.

18 19

CCSU v. Minister for Civil Service, [1985] AC 374 (Lord Roskill). Begbie, [2000] 1 WLR 1115 (CA).

VI Semester Administrative Law 7 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

also relied upon;20 the trust that has been reposed by the citizen in what he has been told or led to believe by the official.21 When is an expectation legitimate? First, it must be founded upon a promise or practice by the public authority that is said to be bound to fulfil the expectation. Second, clear statutory words override any expectation howsoever founded.22 Third, the notification of a relevant change of policy destroys any expectation founded upon the earlier policy.23 Fourth, the individual seeking protection of the expectation must themselves deal fairly with the public authority.24

How can a legitimate expectation arise?

In CCSU v. Minister for Civil Service, Lord Fraser identifies two ways by which a legitimate expectation can arise: legitimate expectation may arise from either an express promise given on behalf of the public authority or from the existence of a regular practice which the claimant can reasonably expect to continue.25 1. Express Promise: The most common way a legitimate expectation might arise is by an express promise or specific representation to an individual or group. In R. v. Liverpool Taxi Fleet Association,26 an express promise from the Liverpool Corporation that it would not increase the number of taxi licenses in the area without consultation with the Association was held to create a legitimate expectation of consultation.27

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

CRAIG, supra note 5 at 649. WADE & FORSYTH, supra note 5 at 447. R. v. DPP ex p. Kebilene, [1999] 3 WLR 972 (HL). Fisher v. Minister of Public Safety, [1999] 2 WLR 349. R. v. Inland Revenue Commissioners ex. p. MFK Underwriting Agencies [1990] 1 WLR 1545. [1985] AC 374, 401. See, CLIVE LEWIS, JUDICIAL REMEDIES IN PUBLIC LAW, 272 (3rd edn, 2004). [1972] 2 QB 299.

See also, R. v. Devon County Council ex.p. Baker, [1995] 1 All E.R. 73 (CA); R v. Secretary of State for Transport, ex.p. Richmond-upon-Thames LBC, [1994] 1 WLR 74 (QB).

VI Semester Administrative Law 8 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

2. Existence of Regular Practice: In CCSU case,28 where continuous practice of consultation before changes to conditions of service led to the legitimate expectation there would be consultation before the Minister abolished the membership of the trade union. 3. Certain Criteria must be satisfied for the promise or practice to gain legal enforceability in public law: The promise must be clear, unambiguous and precise.29The promise of a hearing before a decision is taken may give rise to a legitimate expectation that the hearing will be given.30 The legitimate expectation must be legal. It should be within the powers of the body to make the representation and fulfill it.31 Knowledge of policy but not reliance to ones own detriment.32 If the individual has suffered no hardship, there would be no reason to hold the decision-maker to its promise.33

Standard of Review for breach of legitimate expectation

In R. (Bibi) v. Newham London Borough Council,34 the Court of Appeal gave guidance on how the court should approach legitimate expectation cases with three practical questions: First, what has the public authority, whether by promise or practice, committed itself to; second, whether the authority has acted or proposed to act unlawfully in relation to its commitment; third, what the court should do in this regard. L. J. Laws in Abdi and Nadarajah v. Secretary of State for Home Department,35 advocated a test of proportionality for judicial review of administrative action on the basis of legitimate expectation. This precedent sheds some light on whether proportionality could be used and adjusted to give due weight to the fact that the decision-maker nay have greater expertise and/or democratic legitimacy than the court, and the court could apply the test with varying

28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

Supra note 23. Begbie and Kebilene, supra note 20. Attorney General of Hong-Kong v. Ng Yeun Shiu, [1983] 2 AC 629. Bibi, [2001] EWCA Civ 607; Hamble, supra note 14 at 731; Flanagan, [2002] EWCA Civ 690. Rashid, [2005] EWCA Civ. 744. Bibi, supra note 31. Id. [2005] EWCA Civ. 1363.

VI Semester Administrative Law 9 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

degrees of intensity by scrutinizing more or less closely a decision-makers claims that it was necessary to frustrate the applicants expectation.36

JUDICIAL DEVELOPMENT OF LEGITIMATE EXPECTATIONS IN INDIA

Some Supreme Court cases that have recently dealt with the doctrine of legitimate expectation are: In J.P.Bansal v State of Rajasthan,37 the Supreme Court while examining the doctrine of legitimate expectation held that: The principle of legitimate expectation is at the root of the rule of law and requires regularity, predictability and certainty in governments dealings with the public. For a legitimate expectation to arise, the decisions of the administrative authority must affect the person by depriving him of some benefit or advantage which either: (i) he had in the past been permitted by the decision maker to enjoy and which he can legitimately expect to be permitted to continue to do until there has been communicated to him some rationale grounds for withdrawing it or where he has been given an opportunity to comment; or (ii) he has received assurance from the decision maker that they will not be withdrawn without giving him first an opportunity of advancing reasons for contending that they should not be withdrawn. The procedural part of it relates to a representation that a hearing or other appropriate procedure will be afforded before the decision is made. The substantive part of the principle is that if a representation is made than a benefit of substantive nature will be granted or if the person is already in receipt of the benefit than it will be continued and not be substantially varied, then the same could be enforced. An exception could be based on an express promise or representation or by established past action or settled conduct. The representation must be clear and unambiguous. It could be a representation to an individual or to a class of persons.

In another case, Punjab Communications Ltd v. Union of India (1999),38 the Supreme Court cited British precedents (especially Hargreaves) to suggest that whether a legitimate expectation can be legally frustrated on public interest grounds can only be

36 37 38

ELIZABETH GIUSSANI, CONSTITUTIONAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW, 329 (1st ed, 2008). 2003(3) SCALE 154.

1999 (4) SCC 727. Supreme Court of India judgment dated 04 May 1999. See also, M/S Sethi Auto Service Station & Ors. v. Delhi Development Authority & Ors dated 17 October 2008.

VI Semester Administrative Law 10 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

judged by the very deferential standards of Wednesbury unreasonableness, and nor the more demanding test of proportionality. It also went on to note that the doctrine of legitimate expectation in the substantive sense has been accepted as part of [Indian] law and that the decision maker can normally be compelled to give effect to his representation in regard to the expectation based on previous practice or past conduct unless some overriding public interest comes in the way. In MRF Ltd Kottayam vs Asst Commissioner, Sales Tax,39 it was observed that the protection of legitimate expectation does not require the fulfillment of such expectation where an overriding public interest requires otherwise. That is to say, the public interest is overriding. Therefore, what becomes clear is that legitimate expectations as a ground for challenging administrative action can be done away with when there is an overriding public interest and the immediacy of the situation required a change in policy, moving away from past promises and practice. Recently, a Constitution Bench of the SC in Secretary, State of Karnataka v. Umadevi,40 referred to the circumstances in which the doctrine of legitimate expectation can be invoked thus : The doctrine can be invoked if the decisions of the administrative authority affect the person by depriving him of some benefit or advantage which either (i) he had in the past been permitted by the decision-maker to enjoy and which he can legitimately expect to be permitted to continue to do until there have been communicated to him some rational grounds for withdrawing it on which he has been given an opportunity to comment; or (ii) he has received assurance from the decision-maker that they will not be withdrawn without giving him first an opportunity of advancing reasons for contending that they should not be withdrawn.

Another Constitution Bench, referring to the doctrine, observed thus in Confederation of Ex-servicemen Associations vs. Union of India:41 No doubt, the doctrine has an important place in the development of Administrative Law and particularly law

39

Supreme Court of India judgment dated 21 September 2006. See, Sukumar Mukhopadhyay, Legitimate Expectation and Public Interest, Business Standard, 11 December 2006.

40 41

2006 (4) SCC 1. JT 2006 (8) SC 547.

VI Semester Administrative Law 11 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

relating to 'judicial review'. Under the said doctrine, a person may have reasonable or legitimate expectation of being treated in a certain way by an administrative authority even though he has no right in law to receive the benefit. In such situation, if a decision is taken by an administrative authority adversely affecting his interests, he may have justifiable grievance in the light of the fact of continuous receipt of the benefit, legitimate expectation to receive the benefit or privilege which he has enjoyed all throughout. Such expectation may arise either from the express promise or from consistent practice which the applicant may reasonably expect to continue. In such cases, therefore, the Court may not insist an administrative authority to act judicially but may still insist it to act fairly. The doctrine is based on the principle that good administration demands observance of reasonableness and where it has adopted a particular practice for a long time even in absence of a provision of law, it should adhere to such practice without depriving its citizens of the benefit enjoyed or privilege exercised. As to who can invoke the protection of legitimate expectation, the SC has observed, after examining a list of authorities on the subject, that: The doctrine of legitimate expectation based on established practice (as contrasted from legitimate expectation based on a promise), can be invoked only by someone who has dealings or transactions or negotiations with an authority, on which such established practice has a bearing, or by someone who has a recognized legal relationship with the authority-A total stranger unconnected with the authority or a person who had no previous dealings with the authority and who has not entered into any transaction or negotiations with the authority, cannot invoke the doctrine of legitimate expectation, merely on the ground that the authority has a general obligation to act fairly.42 In Food Corporation of India v. Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries Ltd,43 the Supreme Court has observed that the doctrine of legitimate expectation falls within the purview of the principle of non-arbitrariness as incorporated under Article 14 of the Constitution. It becomes an enforceable right when the Government instrumentality fails to give due weight to it.

42 43

Ram Pravesh Singh & Ors. v.State of Bihar & Ors., 2006 (8) SCJ 721. AIR 1993 SC 1601.

VI Semester Administrative Law 12 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

However, as per the observations of the Supreme Court in Assistant Excise Commissioner v. Issac Peter,44 the doctrine of legitimate expectation cannot be invoked to alter the terms of a contract of a statutory nature. Similarly, in Howrah Municipal Corporation v. Ganges Road Company Ltd45 it has been held that no right can be claimed on the basis of legitimate expectation when it is contrary to statutory provisions which have been enforced in public interest.

In Madras City Wine Merchants Association v. State of Tamil Nadu46 the doctrine of legitimate expectation was held to become inoperative when there was a change in public policy or in public interest as has been reaffirmed in some of the aforementioned decisions.

In Union of India v. Hindustan Development Corporation,47 the Supreme Court has elaborately considered the reverence of this theory. In the estimation of the Apex Court, the doctrine does not contain any crystallized right. It gives to the applicant a sufficient ground to seek judicial review and the principle is mostly confined to the right to a fair hearing before any decision is given.

It was held in Navjyoti Co-op Group Housing Society v. Union of India48 that the doctrine of legitimate expectation imposes in essence a duty on the public authorities to act fairly by taking into consideration all the relevant factors bearing a nexus to such legitimate expectation. The concerned authority cannot act arbitrarily so as to defeat the expectation, unless demanded by over-riding reasons of public policy.

Further, in another landmark judgment, M.P. Oil Extraction Co v. State of Madhya Pradesh,49 the Supreme Court was dealing with the license renewal claims of certain industries. It was held in this case that extending an invitation, on behalf of the State,

44 45 46 47 48 49

(1994) 4 SCC 104. (2004) 1 SCC 663. (1994) 5 SCC 509. AIR 1994 SC 988. AIR 1993 SC 155. Supra note 2.

VI Semester Administrative Law 13 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

was not arbitrary and the selected industry had a legitimate expectation of renewal of license under the renewal claims. Lastly, in National Building Constructions Corporation v. S Raghunathan50 it was held that legitimate expectation is a source of both, procedural and substantive rights. The person seeking to invoke the doctrine must be aggrieved and must have altered his position. The doctrine of legitimate expectation assures fair play in administrative action and can always be enforced as a substantive right. Whether or not an expectation is legitimate is a question of fact.

The development of the doctrine of legitimate expectation in India has been in line with the principles evolved in common law English courts. In fact, it was from these English cases itself that the doctrine first came to be recognized by the courts in India. It therefore creates a new category of remedy against an administrative action and furthers the rule of law in India.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

As Wade & Forsyth believe, the doctrine of legitimate expectations is a welcome addition to the armoury of the courts ensuring that discretions are exercised fairly. The phrase legitimate expectation, which is much in vogue,51 must not be allowed to collapse into an inchoate justification for judicial intervention.52 Academics have expressed skepticism as to whether the doctrine of legitimate expectation should apply to substantive rights. Thio Li-ann argues that legitimate expectations should relate only to procedural rather than substantive rights.53 Procedural protection only has a minimal impact on the administrative autonomy of the relevant public authority, since the court is only concerned with the manner in which the decision was made and not whether the decision was fair. Thus, the ultimate autonomy of public authorities is never placed in

50 51 52 53

AIR 1998 SC 2776. R. (EB Kosovo) v. Home Secretary, [2008] UKHL 41. (Lord Scott) WADE & FORSYTH, supra note 5 at 447.

Thio Li-ann, Law and the Administrative State in KEVIN YEW LEE TAN (ed.), THE SINGAPORE LEGAL SYSTEM, 190 (1996).

VI Semester Administrative Law 14 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

jeopardy.54 Conversely, as Mark Elliot posits, giving effect to a substantive legitimate expectation impinges on the separation of powers.55 The authority has been entrusted by Parliament to make decisions about the allocation of resources in public interest. Applying legitimate expectation substantively allows the courts to inquire into the merits of the decision. Such interference with the public authority's discretion would be overstepping their role and exceeding their proper constitutional function. The courts have been taking a more active role in controlling the exercise of discretionary power and upholding the rule of law, while recognizing that in certain situations deference to the Executive is necessary. The courts have to therefore maintain a balance between legitimate judicial intervention and judicial interference violating the principle of separation of powers, and as the concept of legitimate expectations continues to develop, maintaining this balance will be at the forefront.56

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Journal Articles

1. Benny Y T Tai and Kevin K F Yam, The Advent of Substantive Legitimate Expectations in Hong Kong: Two Competing Visions, [2002] Public Law 688. 2. Cameron Stewart, Substantive Unfairness: A New Species of Abuse of Power? 28 Federal Law Review 617 (2000) 3. Daniel Malan Pretorius, Ten Years After Traub:The Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation in South African Administrative Law, 117 S. African L. J. 520 (2000) 4. David Wright, Rethinking The Doctrine Of Legitimate Expectations In Canadian Administrative Law, 35 (1) Osgoode Hall L. J. 139 (1997). 5. Geo Quinot, Substantive Legitimate Expectations in South African and European Administrative Law, 5 (1) German Law Journal 65 (2004). 6. Iain Steele, Substantive Legitimate Expectations: Striking the Right Balance? (2005) 121 Law Quarterly Review 300 7. John Hlophe, Legitimate Expectation and Natural Justice: English Australian and South African Law, 105 S. African L. J. 165 (1987) 8. Lord Irvine of Lairg, The Modern Development of Public Law In Britain; and the Special Impact of European Law, 11 Singapore Academy of L. J. 275 (1999). 9. Mark Elliot, Coughlan: Substantive Protection of Legitimate Expectations Revisited, 5 (1) Judicial Review 27 (2000).

54

Lord Irvine of Lairg, The Modern Development of Public Law In Britain; and the Special Impact of European Law, 11 Singapore Academy of L. J. 275 (1999).

55

Mark Elliot, Coughlan: Substantive Protection of Legitimate Expectations Revisited, 5 (1) Judicial Review 27 (2000).

56

GIUSSANI, supra note 36 at 220.

VI Semester Administrative Law 15 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

10. Mark Elliott, Legitimate Expectations and the Search for Principle: Reflections on Abdi & Nadarajah [2006] Judicial Review 281 11. Matthew Groves, Substantial Legitimate Expectations in Australian Administrative Law, 32 (2) Melbourne Univ. L. R. 470 (2008) 12. Melanie Roberts, Public Law Representations and Substantive Legitimate Expectations, 64 (1) Modern Law Review 112122 (2001) 13. Robert E. Riggs, Legitimate Expectation and Procedural Fairness in English Law, 36 (3) Am. J. Comp. L. 395 (1988). 14. Sales & Steyn, Legitimate Expectations in English Law: An Analysis, (2004) Public Law 564653 15. Shantimal Jain, Legitimate Expectation-A Confusing Cauldron, The Chartered Accountant, October 2003, 427-9. 16. Teresa Martin, Hong Kong Right of Abode: Ng Siu Tung & Others v Director of Immigration Constitutional and Human Rights at the Mercy of China, 5 San Diego International Law Journal 465 (2004).

Books and Treatises

1. B. C. Sarma, The Law of Ultra Vires (Eastern Law House, 2004) 2. Bradley & Ewing, Constitutional and Administrative Law (13th edn., 2003). 3. Cameron Stewart, The Doctrine of Substantive Unfairness and the Review of Substantive Legitimate Expectations in Matthew Groves and H P Lee (eds), Australian Administrative Law: Fundamentals, Principles and Doctrines 280 (2007). 4. Clive Lewis, Judicial Remedies in Public Law (3rd edn, 2004). 5. Elizabeth Giussani, Constitutional and Administrative Law (1st ed, 2008). 6. Harlow & Rawlings, Law and Administration (3rd edn., 2009). 7. Hilaire Barnett, Constitutional and Administrative Law (1997). 8. Jain & Jain, Principles of Administrative Law (6th ed, 2010). 9. Michael T Molan (ed.), 150 Leading Cases in Constitutional and Administrative Law (2nd edn., 2002). 10. Neil Papworth, Constitutional and Administrative Law (5th edn., 2008). 11. P P Craig, Administrative Law (5th ed, 2003). 12. Paul Craig, Administrative Law (6th ed, 2008) 13. Peter Cane, An Introduction to Administrative Law (3rd edn., 1996). 14. Robert Thomas, Legitimate Expectations and Proportionality in Administrative Law (2000). 15. Schnberg, Legitimate Expectations in Administrative Law (2000). 16. Thio Li-ann, Law and the Administrative State in KEVIN YEW LEE TAN (ed.), THE SINGAPORE LEGAL SYSTEM (1996). 17. William Wade & Christopher Forsyth, Administrative Law (10th ed, 2009)

Caselaw

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. National Building Constructions Corporation v. S Raghunathan, AIR 1998 SC 2776. R. (EB Kosovo) v. Home Secretary, [2008] UKHL 41. Navjyoti Co-op Group Housing Society v. Union of India AIR 1993 SC 155. Assistant Excise Commissioner v. Issac Peter (1994) 4 SCC 104. Ram Pravesh Singh & Ors. v. State of Bihar & Ors., 2006 (8) SCJ 721. Howrah Municipal Corporation v. Ganges Road Company Ltd (2004) 1 SCC 663.

VI Semester Administrative Law 16 Doctrine of Legitimate Expectations

7. M/S Sethi Auto Service Station & Ors. v. Delhi Development Authority & Ors dated 17 October 2008. 8. J.P.Bansal v State of Rajasthan 2003(3) SCALE 154. 9. Madras City Wine Merchants Association v. State of Tamil Nadu (1994) 5 SCC 509. 10. Food Corporation of India v. Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries Ltd AIR 1993 SC 1601. 11. Secretary, State of Karnataka v. Umadevi, 1999 (4) SCC 727. 12. Attorney General of Hong-Kong v. Ng Yeun Shiu, [1983] 2 AC 629. 13. Bibi, [2001] EWCA Civ 607 14. Flanagan, [2002] EWCA Civ 690. 15. Rashid, [2005] EWCA Civ. 744. 16. R. v. DPP ex p. Kebilene, [1999] 3 WLR 972 (HL). 17. Fisher v. Minister of Public Safety, [1999] 2 WLR 349. 18. Ex. P. Hamble (Offshore) Fisheries Ltd [1995] 2 All. E.R. 714, 724 19. Hargreaves, [1997] 1 WLR 906. 20. Coughlan, [2001] QB 213. 21. Begbie, [2000] 1 WLR 1115 (CA). 22. CCSU v. Minister for Civil Service [1985] AC 374, 401. 23. R. v. Liverpool Taxi Fleet Association [1972] 2 QB 299. 24. Re Siah Mooi Guat, [1988] 2 S.L.R. (R.) 165, H.C 25. Union of India v. Hindustan Development Corpn., (1993) 3 SCC 499. 26. M.P. Oil Extraction Co. v. State of M.P., (1997) 7 SCC 592. 27. Chanchal Goyal (Dr.) v. State of Rajasthan, (2003) 3 SCC 485. 28. Tung v Director of Immigration [2002] 1 HKLRD 561, 600 (Li CJ, Chan and Ribeiro PJJ and Mason NPJ). 29. R. v. Devon County Council ex.p. Baker, [1995] 1 All E.R. 73 (CA) 30. R v. Secretary of State for Transport, ex.p. Richmond-upon-Thames LBC, [1994] 1 WLR 74 (QB).

You might also like

- Doctrine of Legitimate ExpectationDocument13 pagesDoctrine of Legitimate ExpectationFaizaanKhanNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Legitimate ExpectationDocument13 pagesAdmin Law Legitimate ExpectationAnushka TRivediNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Legitimate ExpectationDocument9 pagesDoctrine of Legitimate ExpectationShweta Tomar100% (1)

- Uncitral Model Law of ArbitrationDocument33 pagesUncitral Model Law of ArbitrationSaurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence FullerDocument19 pagesJurisprudence FullerAdrew Luccas100% (1)

- Tigist AssefaDocument135 pagesTigist AssefaPuneet Tigga100% (1)

- Policy Considerations For SurrogacyDocument22 pagesPolicy Considerations For SurrogacySatyajeet ManeNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1986 - Final EditDocument7 pagesA Review of The Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, 1986 - Final EditAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Triple Talaq Case BriefDocument2 pagesTriple Talaq Case BriefRishabh DubeyNo ratings yet

- The Theory Rule of Law Between Uk and Bangladesh: Reality and PracticeDocument21 pagesThe Theory Rule of Law Between Uk and Bangladesh: Reality and PracticeTawhidur Rahman Murad100% (2)

- Intention To Create Legal RelationsDocument12 pagesIntention To Create Legal RelationsdraxtterNo ratings yet

- Legitimate Expectaion ConstiDocument10 pagesLegitimate Expectaion ConstiFongVoonYukeNo ratings yet

- Project-Law of Crimes: Amithab Sankar 1477 Semester 5Document6 pagesProject-Law of Crimes: Amithab Sankar 1477 Semester 5Sankar100% (1)

- Gifts Under Muslim LawDocument4 pagesGifts Under Muslim LawGarima Bhargava0% (1)

- Innovation in Interpretation: Analysis of Judicial Lawmaking in IndiaDocument7 pagesInnovation in Interpretation: Analysis of Judicial Lawmaking in Indiatanshi bajajNo ratings yet

- Stockholm 1972 - DeclarationDocument4 pagesStockholm 1972 - DeclarationRubenENE0% (1)

- 3 Natural Law and The Malaysian Legal System PDFDocument9 pages3 Natural Law and The Malaysian Legal System PDFkeiraNo ratings yet

- Research Work PDFDocument13 pagesResearch Work PDFSukriti ShuklaNo ratings yet

- 6 Minor Acts PDFDocument165 pages6 Minor Acts PDFMadhav BhatiaNo ratings yet

- I.C. Golaknath and Ors. Vs State of Punjab and Anrs. - Wikipedia PDFDocument18 pagesI.C. Golaknath and Ors. Vs State of Punjab and Anrs. - Wikipedia PDFHarshdeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Gmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawDocument7 pagesGmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawShivam MishraNo ratings yet

- Administrative LawDocument22 pagesAdministrative LawDhruv MalikNo ratings yet

- Evidence Presumption As To DocumentsDocument37 pagesEvidence Presumption As To DocumentsAryan SinghNo ratings yet

- PIL 2 (Nottebohm Case Presentation) Group 1Document16 pagesPIL 2 (Nottebohm Case Presentation) Group 1adityaNo ratings yet

- Administrative Discretion and JRDocument5 pagesAdministrative Discretion and JRSurya ShreeNo ratings yet

- Statute and Types of StatutesDocument7 pagesStatute and Types of StatutesMohammad IrfanNo ratings yet

- Judicial Trends in Water Law Case Study': Veera Kaul Singh and Bharath JairafDocument18 pagesJudicial Trends in Water Law Case Study': Veera Kaul Singh and Bharath Jairafashwani100% (1)

- Conflict of Law NotesDocument11 pagesConflict of Law Notesfarheen haiderNo ratings yet

- University Institute of Legal StudiesDocument15 pagesUniversity Institute of Legal StudiesNimrat kaurNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance in A Developing Economy: Barriers, Issues, and Implications For FirmsDocument16 pagesCorporate Governance in A Developing Economy: Barriers, Issues, and Implications For FirmsTahir ZahoorNo ratings yet

- DowerDocument35 pagesDowerROHITGAURAVNo ratings yet

- Right To PrivacyDocument6 pagesRight To PrivacyAbhishek KumarNo ratings yet

- LokpalDocument39 pagesLokpalNari AkilNo ratings yet

- Vi Vii IxDocument18 pagesVi Vii IxArushiNo ratings yet

- Clinical ProjectDocument45 pagesClinical ProjectTusharGuptaNo ratings yet

- COMPANY LAW Majority Rule and Minority PDocument13 pagesCOMPANY LAW Majority Rule and Minority PPrakriti SinghNo ratings yet

- Special and Differential Treatment For Developing Countries: by Thomas FritzDocument47 pagesSpecial and Differential Treatment For Developing Countries: by Thomas FritzNIKHIL SODHINo ratings yet

- Week-11 Dualist and Monist TheoriesDocument5 pagesWeek-11 Dualist and Monist TheoriesApoorva YadavNo ratings yet

- Final Draft PDFDocument14 pagesFinal Draft PDFPee KachuNo ratings yet

- 52, Prachi Tatiwal, IL, Final DraftDocument21 pages52, Prachi Tatiwal, IL, Final DraftGarvit ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 4) Civil Procedure Code: Salient FeaturesDocument19 pages4) Civil Procedure Code: Salient FeaturesRahul ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Research Regarding Corporate VeilDocument12 pagesIntroduction To Research Regarding Corporate VeilFaisal AshfaqNo ratings yet

- Judges Make Laws or They Merely Declare ItDocument7 pagesJudges Make Laws or They Merely Declare ItasthaNo ratings yet

- Contractual Liability of The State in IndiaDocument10 pagesContractual Liability of The State in IndiaSatyam KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of ProportionalityDocument8 pagesDoctrine of Proportionalityanshita maniNo ratings yet

- Liberalisation of Legal Services in India Through GATSDocument14 pagesLiberalisation of Legal Services in India Through GATSGovind Singh TomarNo ratings yet

- Right To PrivacyDocument5 pagesRight To PrivacyutkarshNo ratings yet

- S V Malumo and 24 Others Supreme Court Judgment 2Document24 pagesS V Malumo and 24 Others Supreme Court Judgment 2André Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Romisha Gurung CPCDocument15 pagesRomisha Gurung CPCAkansha Kashyap100% (1)

- Humanitarian InterventionDocument23 pagesHumanitarian InterventionYce FlorinNo ratings yet

- The Presentation Is Only Illustrative and Not ExhausitiveDocument97 pagesThe Presentation Is Only Illustrative and Not ExhausitiveUjjwal AnandNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Development: A Project ReportDocument40 pagesSustainable Development: A Project Reportshivanika singlaNo ratings yet

- The Idea-Expression Merger Doctrine: Project OnDocument8 pagesThe Idea-Expression Merger Doctrine: Project OnChinmay KalgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Right To PrivacyDocument13 pagesRight To PrivacyMujassimNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra National Law University Mumbai: Promoters-Duties, Liabilities and Rights'Document11 pagesMaharashtra National Law University Mumbai: Promoters-Duties, Liabilities and Rights'Ayashkant ParidaNo ratings yet

- Postponement of Death Sentence & Its EffectDocument11 pagesPostponement of Death Sentence & Its EffectDharu LilawatNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Legitimate Expectation: An Analysis: December 2020Document15 pagesDoctrine of Legitimate Expectation: An Analysis: December 2020Sheela AravindNo ratings yet

- Strict LiabilityDocument5 pagesStrict LiabilityNg Yih Miin100% (2)

- Situating Automatism in The Penal Codes of Malaysia and SingaporeDocument28 pagesSituating Automatism in The Penal Codes of Malaysia and SingaporeNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Strict LiabilityDocument5 pagesStrict LiabilityNg Yih Miin100% (2)

- Justice Delayed Is Justice Denied?: Divorce Case Management in Malaysian Shariah CourtDocument11 pagesJustice Delayed Is Justice Denied?: Divorce Case Management in Malaysian Shariah CourtNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Sieh Kok Chi Malaysian Olympic CouncillDocument2 pagesSieh Kok Chi Malaysian Olympic CouncillNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

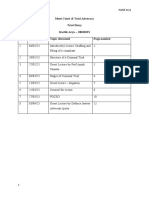

- Lecture 4 Individual Statutory Rights Affecting The Course of Employment Lecture VersionDocument51 pagesLecture 4 Individual Statutory Rights Affecting The Course of Employment Lecture VersionNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Justice Delayed Is Justice Denied?: Divorce Case Management in Malaysian Shariah CourtDocument11 pagesJustice Delayed Is Justice Denied?: Divorce Case Management in Malaysian Shariah CourtNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Islamic AssignmentDocument5 pagesIslamic AssignmentNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Islamic Law PresentationDocument21 pagesIslamic Law PresentationNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- What Is FencingDocument3 pagesWhat Is FencingNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Employment LawDocument7 pagesEmployment LawNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Ifla Question Tutorial IonDocument5 pagesIfla Question Tutorial IonNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- KP and KCDocument30 pagesKP and KCNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Assignment Criminal 2011 Sem 2Document2 pagesAssignment Criminal 2011 Sem 2Ng Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Defence For EddiesDocument3 pagesDefence For EddiesNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- CasesDocument1 pageCasesNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- BigamyDocument2 pagesBigamyNg Yih MiinNo ratings yet

- Actus Reus Case LawDocument7 pagesActus Reus Case LawNg Yih Miin100% (3)

- Notes On AtienzaDocument3 pagesNotes On AtienzaJon Gabriel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Professional Ethical StandardsDocument2 pagesProfessional Ethical StandardspanerjNo ratings yet

- Year 4 - QHDocument4 pagesYear 4 - QHRoshanNo ratings yet

- Examination Under Law of EvidenceDocument22 pagesExamination Under Law of Evidencechanakyanationallaw100% (1)

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Submitted ToDocument16 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Submitted ToAkankshaNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Notes - Right Duties Owner PossesDocument14 pagesJurisprudence Notes - Right Duties Owner PossesPriyank SaxenaNo ratings yet

- MPRE Subject Matter OutlineDocument1 pageMPRE Subject Matter Outlinekyw123No ratings yet

- Doctrine of 'Precedent' in India - SRD Law NotesDocument3 pagesDoctrine of 'Precedent' in India - SRD Law Notescakishan kumar guptaNo ratings yet

- Police Custody and Judicial CustodyDocument14 pagesPolice Custody and Judicial Custodyjyotak vatsNo ratings yet

- (PDF) Criminal Law Bar Exam Questions and Answers - Ryan James Aban - Academia - EduDocument90 pages(PDF) Criminal Law Bar Exam Questions and Answers - Ryan James Aban - Academia - EduTheenaNo ratings yet

- JurisprudenceDocument8 pagesJurisprudenceShiela Mae BalbastroNo ratings yet

- Persons SummaryDocument11 pagesPersons SummaryJo Rizza CalderonNo ratings yet

- Jagmohan Singh VS State of UpDocument3 pagesJagmohan Singh VS State of Up78 Harpreet Singh100% (1)

- MCTA Lecture Diary - Kartik AryaDocument12 pagesMCTA Lecture Diary - Kartik Aryakartik aryNo ratings yet

- IHL React 3 - TerrazolaDocument2 pagesIHL React 3 - TerrazolaleiNo ratings yet

- Unit 5Document39 pagesUnit 5full sunNo ratings yet

- Intrebari Limba Engleza 2 - An1 Sem 2Document12 pagesIntrebari Limba Engleza 2 - An1 Sem 2Sorica VioricaNo ratings yet

- Lalita Kumari Vs Government of UP & Others, 2013Document5 pagesLalita Kumari Vs Government of UP & Others, 2013Pankaj Shukla100% (1)

- Group 8 - Evidence According To Indonesian Criminal Procedure LawDocument14 pagesGroup 8 - Evidence According To Indonesian Criminal Procedure LawEkeh Celestine ChigozieNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights J Article 3 of The ConstitutionDocument6 pagesBill of Rights J Article 3 of The ConstitutionJovy C. AndresNo ratings yet

- Go v. Estate of BuenaventuraDocument10 pagesGo v. Estate of BuenaventuraKiko BautistaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Public International LawDocument53 pagesNotes On Public International LawRohit Mehta100% (1)

- People Vs AbrazaldoDocument12 pagesPeople Vs AbrazaldoThrees SeeNo ratings yet

- Mitigating CircumstancesDocument32 pagesMitigating CircumstancesJay Sta MariaNo ratings yet

- Ca3 Chapter 1-2Document17 pagesCa3 Chapter 1-2Ragie castaNo ratings yet

- Ed 26. Napocor V Heirs of Macabangkit SangkayDocument3 pagesEd 26. Napocor V Heirs of Macabangkit SangkayEileen Eika Dela Cruz-LeeNo ratings yet

- Writ of Amparo Writ of Habeas Data (Reviewer)Document3 pagesWrit of Amparo Writ of Habeas Data (Reviewer)Jazztine ArtizuelaNo ratings yet

- Color Wheel Theory of LoveDocument1 pageColor Wheel Theory of LoveKurt Micaela AcolNo ratings yet

- Manifest Failure The Gettier Problem SolvedDocument11 pagesManifest Failure The Gettier Problem SolvedIsabelIbarraNo ratings yet

- Criminal InformationDocument2 pagesCriminal InformationEman de VeraNo ratings yet