Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kenyan Suspects To Remain Free During ICC Trials

Uploaded by

iwprJusticeNewsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kenyan Suspects To Remain Free During ICC Trials

Uploaded by

iwprJusticeNewsCopyright:

Available Formats

Kenyan Suspects to Remain Free During ICC Trials But threats to witnesses and concerns about election campaign

raise questions ab out defendants continued freedom. By Judie Kaberia - International Justice - ICC ACR Issue 326, 13 Jul 12 Four Kenyan suspects indicted by the International Criminal Court, ICC, are to b e allowed to remain at liberty pending trial, and if they remain cooperative, th ey might also stay out of custody during trial. However, some legal experts believe that might change if judges in The Hague dec ide that defendants are breaking the rules that allow them to avoid detention. T hey point to reports that witnesses have been subjected to threats in Kenya, and concerns that political campaigning by the two defendants running for the Kenya n presidency might turn nasty. The trials of Deputy Prime Minister Uhuru Kenyatta, former higher education mini ster William Ruto, cabinet secretary Francis Muthaura, and Kass FM radio present er Joshua Arap Sang are due to start on April 11 and 12, 2013. The four are accused of committing crimes against humanity during the violence t hat erupted in the aftermath of Kenyas 2007 presidential election, which saw clas hes between supporters of the Orange Democratic Movement, ODM, and the Party of National Unity, PNU. The two parties now form a governing coalition. The charges against the four were confirmed by judges on January 23 this year, w hile those the ICC prosecutor was seeking against a further two men were rejecte d, William Schabas, professor of law at Middlesex University, explained why the fou r had been allowed to remain at liberty rather than being transferred to the the United Nations detention unit in The Hague. Release during trial is authorised rather exceptionally by international criminal tribunals when the accused person has surrendered to the court, cooperated with it, and has a stable residence in a jurisdiction that is capable of making an a rrest should the person become non-cooperative, he said. I think all of this is pr esent in the Kenya cases. The defendants cooperation with the ICC will be key to whether they remain free i n the run-up to and during trial proceedings. Should trial judges decide that th e situation has changed, they can alter the terms of the summonses issued in Mar ch 2011, which requires the suspects to appear in The Hague whenever requested t o do so. So far, all four have cooperated, and hence they remain at liberty and are free to travel. During their initial appearance in court in April 2011, pre-trial judges imposed a set of conditions on them, which included avoiding all contact with victims o f the post-election violence or with witnesses; refraining from obstructing or i nterfering with the attendance or testimony of a witness; and not interfering wi th the prosecutions investigation. It is for [judges] to monitor whether there are breaches [of the summons conditio ns], Lorraine Smith of the International Bar Association in The Hague, said. Failu re to comply with these conditions could cause the judges to issue a warrant of arrest.

An arrest warrant can come at any point in proceedings ahead of the trial or dur ing it. If there are reasonable grounds to believe that they may obstruct or endanger the investigations or court proceedings, or to prevent commission of a crime, warra nts of arrest can be issued. Interference with victims and witnesses could be se en as obstructing court proceedings, Smith said. At a status conference at the ICC held on June 11-12, the prosecution raised con cerns about threats to its witnesses and said it was important for the court to ensure their protection. Prosecutors did not indicate who was behind the intimidations, and there are no allegations that threats have come directly from the defendants. I am confident that if there was the slightest suggestion that any of the accused did anything to compromise the safety and security of witnesses, the release wo uld be revoked and they would be detained in The Hague, Schabas said. Suspects with high political ambitions One of the unusual aspects of the Kenyan trials at the ICC is that two of the fo ur defendants Kenyatta and Ruto are hoping to become their countrys next presiden t. This weeks announcement of April 11-12 trial dates leaves both men free to contes t an election set for March 4, 2013, a month before proceedings get under way. Political turbulence during the election campaign period, and the possible behav iour of either defendant if elected president, could affect their relationship w ith the ICC and prompt judges to issue arrest warrants. Ruto and Kenyatta both command a huge following, and recently registered their o wn political parties. Thousands of people turned out on May 20 when Kenyatta launched his National All iance party in Nairobi. Ruto had already launched his United Republican Party in January to huge acclaim. With a recent history of election-related communal violence, all eyes will be on the candidates grassroots supporters. James Gondi, director of the International Centre for Transitional Justice in Ke nya, is concerned that Ruto and Kenyatta have been electioneering in ways that m ight incite communities against one another. This is serious,Gondi said. The two are engaged in political sideshows prayer ralli es and ethnic meetings. They are designed to galvanise ethnic bloc, perhaps even to renew violence in the event that the court reaches the conclusion that these persons are guilty. These are dangerous developments. We ought to be concerned. Both Kenyatta and Ruto have denied using rallies to incite violence. (See Fears of Tension Grow in Kenya.) Even so, Gondi believes there is no reason for the court to issue arrest warrant s as long as Kenya upholds its legal duty to cooperate with the ICC. Esther Waweru, a programme officer for legal affairs at the Kenya Human Rights C ommission, is concerned about the negative groundswell that would follow a trial

judgement against either man. When those things [you wanted] do not happen and you have a following such as the y have, then unfortunately that may spur violence, Waweru said. Despite the cooperative behaviour of the Kenyan state as well as all four defend ants so far, some experts say the mood might change once the trial starts. Previous efforts by the Nairobi government to have the trials thrown out by the ICC, or transferred back to Kenya, have led to concerns about the governments wil lingness to stand by proceedings once they actually start. George Kegoro, executive director of the International Commission of Jurists in Kenya, suspects that the presidential bids by Kenyatta and Ruto are a strategy t o block continued government cooperation with the ICC. Asking elections to be held before trials is another way of saying, give us a chan ce to become president where we will be in a position to decide whether Kenya co operates [with the ICC] or not, Kegoro said. Obviously, [what they want] is to ensu re cooperation does not happen. They have gone about making themselves larger th an life even if Kenya wanted to cooperate, they want to make it not happen. Both Ruto and Kenyatta have argued that, if elected president, they would lead K enya in a process of healing and reconciliation. They have portrayed themselves as peacemakers who have never sought to divide the Kenyan people. Kenyas minister for justice, cohesion and constitutional affairs, Eugene Wamalwa, this week, reiterated that the government was supportive of the ICC process. ICC cases are a judicial process that should not be politicised and we should let the law take its course for justice to be done for both the victims and the acc used, he said. Judie Kaberia is an IWPR-trained reporter in Nairobi.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Working of InstitutionsDocument33 pagesWorking of InstitutionsNeeyati BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Effective Justice Key To Lasting PeaceDocument3 pagesEffective Justice Key To Lasting PeaceiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Serb Paramilitaries Wrought Havoc in BosniaDocument4 pagesSerb Paramilitaries Wrought Havoc in BosniaiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Calm Urged As Kenya Vote Count ContinuesDocument5 pagesCalm Urged As Kenya Vote Count ContinuesiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Mladic Trial Examines Single Bomb AttackDocument3 pagesMladic Trial Examines Single Bomb AttackiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Serbian Relief at Perisic RulingDocument4 pagesSerbian Relief at Perisic RulingiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- No Criminal Charges For Dutch Officers Srebrenica RoleDocument3 pagesNo Criminal Charges For Dutch Officers Srebrenica RoleiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Witness Seized "Last Chance" To Escape Vukovar MassacreDocument4 pagesWitness Seized "Last Chance" To Escape Vukovar MassacreiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Karadzic The Good DemocratDocument3 pagesKaradzic The Good DemocratiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Film Success For IWPR TraineeDocument2 pagesFilm Success For IWPR TraineeiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Sarajevo Museum in PerilDocument4 pagesSarajevo Museum in PeriliwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Karadzic Subpoena Request Turned DownDocument2 pagesKaradzic Subpoena Request Turned DowniwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Convicted Bosnian Serb Officer DiesDocument2 pagesConvicted Bosnian Serb Officer DiesiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- "Bosniaks To Blame For 1992 Fighting" - Karadzic WitnessesDocument4 pages"Bosniaks To Blame For 1992 Fighting" - Karadzic WitnessesiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Yugoslav Army Chief Acquitted On AppealDocument4 pagesYugoslav Army Chief Acquitted On AppealiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Karadzic Seeks One-Month Trial SuspensionDocument2 pagesKaradzic Seeks One-Month Trial SuspensioniwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Land Reform Centre-Stage in Kenyan ElectionDocument4 pagesLand Reform Centre-Stage in Kenyan ElectioniwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Survivor Tells of Bosniak Volunteers Selected For DeathDocument4 pagesSurvivor Tells of Bosniak Volunteers Selected For DeathiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Defence Witness Rounds On KaradzicDocument4 pagesDefence Witness Rounds On KaradziciwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Kenyan Suspects Seek ICC Trial DelayDocument4 pagesKenyan Suspects Seek ICC Trial DelayiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Serb Shelling Aimed To Destroy HospitalDocument4 pagesSerb Shelling Aimed To Destroy HospitaliwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Simatovic Granted Provisional ReleaseDocument2 pagesSimatovic Granted Provisional ReleaseiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Prosecuting Mali's ExtremistsDocument6 pagesProsecuting Mali's ExtremistsiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Acting Out Justice in KenyaDocument4 pagesActing Out Justice in KenyaiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Diplomats Issue Rare Warning Ahead of Kenyan PollsDocument5 pagesDiplomats Issue Rare Warning Ahead of Kenyan PollsiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Gbagbo Defence Calls For Charges To Be DroppedDocument3 pagesGbagbo Defence Calls For Charges To Be DroppediwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Tackling Online Hate Speech in KenyaDocument4 pagesTackling Online Hate Speech in KenyaiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Kenya: Presidential Debate Hailed A SuccessDocument5 pagesKenya: Presidential Debate Hailed A SuccessiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Mladic Trial Probes Ballistics of 1994 Markale AttackDocument3 pagesMladic Trial Probes Ballistics of 1994 Markale AttackiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Roving Courts in Eastern CongoDocument8 pagesRoving Courts in Eastern CongoiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

- Bosnian Serb General 'Not Aware' of Plan To Split SarajevoDocument4 pagesBosnian Serb General 'Not Aware' of Plan To Split SarajevoiwprJusticeNewsNo ratings yet

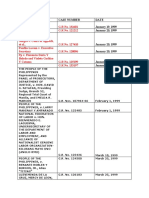

- Case Title Case Number Date January 19, 1999 January 20, 1999Document36 pagesCase Title Case Number Date January 19, 1999 January 20, 1999Raffy LopezNo ratings yet

- Balamban, CebuDocument2 pagesBalamban, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Baras, RizalDocument2 pagesBaras, RizalSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Participation - G7 G10Document66 pagesCertificate of Participation - G7 G10IrvinAironAmigableNo ratings yet

- Tolosa, LeyteDocument2 pagesTolosa, LeyteSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- 2.political PartiesDocument17 pages2.political PartiesNandita KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Mayorga, LeyteDocument2 pagesMayorga, LeyteSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Young Voters and Three Malaysian Parliamentary By-ElectionsDocument22 pagesYoung Voters and Three Malaysian Parliamentary By-Electionstkg groupNo ratings yet

- Political System and State Structure of Pakistan:: Legislature: (Make The Laws)Document2 pagesPolitical System and State Structure of Pakistan:: Legislature: (Make The Laws)chinchouNo ratings yet

- LOKAYUKTADocument10 pagesLOKAYUKTAKeith HuntNo ratings yet

- 3RD Term S2 GovernmentDocument26 pages3RD Term S2 GovernmentFaith OzuahNo ratings yet

- Display PDFDocument19 pagesDisplay PDFVivek PatilNo ratings yet

- 2024 03 19 PPP Election Sample BallotDocument1 page2024 03 19 PPP Election Sample BallotJohn MacLauchlanNo ratings yet

- Dauis, BoholDocument2 pagesDauis, BoholSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Buenavista, MarinduqueDocument2 pagesBuenavista, MarinduqueSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- ILWAS Voter's List 2016Document125 pagesILWAS Voter's List 2016Josh ShinigamiNo ratings yet

- List of Members of The 11th Parliament As at 3rd May 2021Document22 pagesList of Members of The 11th Parliament As at 3rd May 2021kailong wangNo ratings yet

- Final Individual Assignment Damira Aisyah S2124120Document15 pagesFinal Individual Assignment Damira Aisyah S2124120Damira Aisyah AdamNo ratings yet

- Brunei The 1959 ConstitutionDocument4 pagesBrunei The 1959 ConstitutionsedaraNo ratings yet

- British Political SystemDocument26 pagesBritish Political SystemAnonymous VOVTxsQNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 CertificateDocument34 pagesGrade 3 CertificateArlyn Guizo JameraNo ratings yet

- Bais City, Negros OrientalDocument2 pagesBais City, Negros OrientalSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- 54thParlRec FinalDocument423 pages54thParlRec FinalKathy TaylorNo ratings yet

- School Heads MeetingDocument6 pagesSchool Heads MeetingMARIANNE OPADANo ratings yet

- Catarman, CamiguinDocument2 pagesCatarman, CamiguinSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Lame ParliamentDocument18 pagesLame ParliamentShahid SanghaNo ratings yet

- Empowerment of Reserve Components in State Defense Efforts in The Area of Kodam Iii/siliwangi To Support The Land Defense StrategyDocument10 pagesEmpowerment of Reserve Components in State Defense Efforts in The Area of Kodam Iii/siliwangi To Support The Land Defense StrategyLukman Yudho 9440No ratings yet

- CertificatesDocument12 pagesCertificatesCelerinaRusianaLonodNo ratings yet

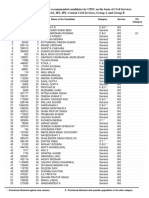

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet