Professional Documents

Culture Documents

글로벌자본주의 위기 (아시아 붕괴)

Uploaded by

revolutin010Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

글로벌자본주의 위기 (아시아 붕괴)

Uploaded by

revolutin010Copyright:

Available Formats

World Socialist Web Site

www.wsws.org

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

Nick Beams, the national secretary of the Socialist Equality Party (Australia), delivered the following public lecture at seven university campuses throughout eastern Australia in late March and early April, 1998. There is no question that the Asian economic and financial meltdown is not just a crisis for this region, but represents a major turning point in the affairs of world capitalism. Indeed, to label this an Asian crisis or an Asian meltdown is something of a misnomer, for the events in Asia are an expression of deep-rooted contradictions within the global economy. A few basic statistics serve to make this clear. During the first half of the 1990s, the Asian region accounted for more than half the growth in world output. According to the latest estimates, however, this region will show negative growth next year. In its World Investment Report for 1996 the UN agency UNCTAD underlined the impor tance of so-called underdeveloped countries for the investment activities of the worlds major corporations, noting that their share in the combined investment outflows of the five largest developed countries rose from 18 percent in 1990-92 to 28 percent in 1993-94. South, East and South-East Asia, it pointed out, continued to be the largest host developing region ... accounting for two thirds of all developing-countr y inflows. The size and dynamism of developing Asia have made it increasingly impor tant for TNCs from all countries to service rapidly expanding markets, or to tap the tangible and intangible resources of that region for global production networks. [World Investment Report 1996, UNCTAD, p. 7] Now capital flows are going in the other direction. After three decades of continuous expansion, economic contraction is underway. The crisis has brought a deep-going recession to Korea the worlds 11th largest economy and has made even more acute the ongoing crisis in Japan, the worlds second largest economy, accounting for 17 percent of global Gross Domestic Product and 65 percent of the AsiaPacific GDP. Since crisis began last July, with the instability surrounding the Thai baht, the region has undergone an unprecedented economic devastation, which can only be partially expressed in figures. The value of the regions currencies has halved since the middle of last year, while the Indonesian rupiah has fallen from around 2,400 to the dollar to around 10,000. The currency has lost three quarters of its value, meaning that the international transactions of major Indonesian companies have come to a standstill. Indonesian banks and corporations which have bor rowed money internationally are technically insolvent, unable to meet private sector debts of more than $60 billion. The chief economist of the National Australia Bank has estimated that only about 20 of Indonesias top 300 corporations are solvent. Indonesia is expected to experience a contraction in its real GDP of anywhere between 10 and 20 percent this year. The lives and social conditions of tens of millions of people are being devastated. Already, according to Indonesian government sources, at least 5.5 million jobs have been destroyed, with the total likely to be double that figure. An economist at the Institute for Economic and Social Research at the University of Jakarta has estimated that some 64 million people will be pushed below the poverty line in the next three to six months. In some parts of the country peasant farmers are already facing starvation as a result, firstly, of the drought, and now the economic collapse. In South Korea, the IMF rescue package is reported to have brought so-called external stability, meaning that the foreign banks are being repaid at least for the moment. But the internal economy has entered a deep

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

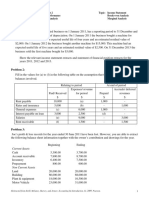

slump. A credit crunch is in force, with interest rates at between 20 and 30 percent. Capital investment is expected to fall by 50 percent and household consumption by 5 percent. In January, imports were down 40 percent from their levels a year earlier. An increasing number of firms will be unable to generate the necessary income to repay domestic debts, estimated at $370 billion. Unemployment in Korea has reached one million, doubling since the crisis began last October. Between 1.5 million and 2 million workers will lose their jobs over the next year. Corporate bankruptcies doubled in the period from last October to January. More than 150 companies go under ever y day. In Januar y alone, bankruptcies totaled 3232. The Office of Bank Supervision has revealed that, as of the end of last year, at least half the countrys commercial banks failed to meet the Bank for International Settlements capital adequacy ratio of 8 percent. The National Statistical Office has reported that in January industrial production was down 10.3 percent from a year ago the biggest decline in more than four decades. In Thailand, where, in contrast to Indonesia, the government of Chuan Leekpai is being hailed as the IMFs model pupil, the economic devastation can be gauged from the latest corporate reports. The 400 companies listed on the Thailand Stock Exchange have recorded their worst losses since the exchange was established in 1975. The Siam Cement Corporation, the countr ys biggest conglomerate, recorded a loss of $1.7 billion or 52 billion baht. The losses due to foreign exchange movements were 56.29 billion baht. If strict corporate standards were applied, most listed companies on the stock exchange would be insolvent. And the worst has yet to come, because around $70 billion of Thailands total foreign debt of $90 billion is owed by the corporate sector and has to be repaid. Overall, the bad loans of the East Asian banks are estimated to account for between 10 and 20 percent of their loan portfolios. Non-performing loans are expected to reach some $73 billion. Economic growth is expected to be negative across the region, so the banking crisis and economic decline will feed off each other. In the words of an article in The Economist magazine of February 27: The danger now in South Korea and elsewhere is that a vicious circle of slowing growth, failing banks and contracting credit will cause not merely a brief and shallow recession but a deep and prolonged slump. 2

Severe as the economic breakdown in Korea and Southeast Asia is, it is in some ways overshadowed by the crisis in Japan. Over the past seven years the Japanese economy has been virtually stagnant, with little or no growth, following the collapse of the sharemarket bubble in the early 1990s. The Japanese crisis had its origins, not in Japan, but in the world economy. In the wake of the global sharemarket collapse of October, 1987, the decision was made that central bankers should not repeat what were considered to be the fatal errors of the 1930s, when credit was restricted. The massive global expansion of credit in the late 1980s led to an unprecedented inflation of stockmarket and land values in Japan. By the end of the 1980s, the real estate value of Tokyo alone was more than three times higher than all the land and buildings in America. The Imperial Palace was worth more than California. The Nikkei stockmarket index reached its peak of just under 39,000 in 1989. Today, it fluctuates between 16,000 and 17,000. The collapse of the financial bubble meant that loans worth hundreds of billions of dollars, supposedly backed by shares, land and buildings, became non-recoverable. The banks which held them were technically insolvent. The Japanese authorities moved in to prop up the banks in the hope that economic growth would enable them to trade out of the crisis and repair their balance sheets. But with growth rates barely above 1 or 2 percent, the position of the banks and financial institutions went from bad to worse. This process could not continue indefinitely. When the financial collapse began in East Asia, it brought the Japanese crisis to a head. In October 1997, the Kyoto Kyoei Bank collapsed with debts of $700 million. This was only the beginning. In November the Tokuyo City Bank fell, owing $6.4 billion, followed by the brokerage firms of Sanyo Securities and Yamaichi Securities ($3 billion and $2.1 billion respectively), the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank ($7 billion). December saw the collapse of the brokerage firm Mauruso Securities ($356 million) and the Toshuko food group ($4.9 billion). The most recent casualty is Daido Concrete Japans second largest supplier of concrete constr uction materials. It folded at the beginning of March with debts of $153 million. While its debts were relatively small in comparison to the failures of the banks and brokerage

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

firms, Daidos demise is significant because it is the first major company to fail as a direct result of the East Asian crisis. When Daido subsidiaries in Hong Kong and Indonesia were unable to repay loans, the banks held the parent responsible. Daido was unable to pay, the banks refused further credit and the company was forced into liquidation. After years of cover-up, the East Asian crisis finally forced Japanese authorities to reveal the real level of debt. Total debt is estimated to be 200 percent of GDP, with bad debts totalling $600 billion, or 15 percent of the Japanese GDP, equivalent to around twice the GDP of Australia. The economic situation in Japan has the most farreaching implications for the world economy, especially when it is recognized that Japans economy is bigger than

those of the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Canada combined. According to a recent article by MIT economist Rudi Dornbusch, in the Far Eastern Economic Review, Japan is in a similar position to that of the United States in the 1920s. Branding Japan as the weakest link in the world economy, he wrote: There must be no doubt that Japan is teetering on the verge of a 1930s-style collapse of financial institutions, confidence and economic activity. ... If everything goes well, the country will just putter along with near-zero growth. If something goes wrong and it does not take much, as we saw when the fall of Yamaichi Securities sparked worries of a nationwide banking collapse Japan will go over the cliff and pull down the Asian region in the process. [Far Eastern Economic Review, February 26, 1998] And one can well add, not only the Asian region, but the world economy as well.

Origins of the Crisis

In seeking to explain how the much-heralded Asian miracle turned into the Asian meltdown, bourgeois economists have placed the blame on a variety of factors, including misdirection of investment, lax lending policies, insufficient supervision of banking, speculation and so on. Such explanations, however, explain nothing. They merely describe the external forms of every crisis since the collapse of the South Sea Bubble in the 18th century. All crises have been preceded by rapid expansions of production and credit, resulting in speculation and highly risky ventures. But this does not mean that crises arise from speculation. On the contrary, a credit boom and collapse is only the appearance of a deeper process the overexpansion of capital and the development of overproduction. The violent swings in capital flows can be seen from the following figures. The five countries which have been hardest hit Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines experienced net private capital inflows of $41 billion in 1994, rising to $93 billion in 1996. Then came the turnaround. In 1997 these same countries were hit by an outflow of $12 billion, sparking the crisis from July 1997 onwards. Precisely because of the regions importance for the world economy, the crisis has had a major impact on the international financial system. The Bank for International Settlements the central bankers bank recently reported that the Asian crisis 3 had threatened the stability of the world banking and financial system. At the turn of the year, states the BIS, the financial turmoil in Asia had reached systemic dimensions, requiring an immediate injection of cash and the rolling over of maturing debt. [International Banking and Financial Market Development, Bank for International Settlements, Basle, February 1998, p. 12] Yet at the very time when, the BIS says, a systemic crisis of the banking system was in the making, the IMF and the World Bank were holding their joint annual meeting to celebrate the Asian miracle and the power of the market. In the repor t prepared for that meeting, held in September 1997, the IMF said of Korea: Directors welcomed Koreas continued impressive macroeconomic performance and praised the authorities for their enviable fiscal record. And likewise on Thailand: Directors strongly praised Thailands remarkable economic performance and the authorities consistent record of sound macroeconomic policies. Only a few weeks after these laudatory statements were issued, however, IMF deputy director Stanley Fischer was to insist that the crisis in Asia was largely homegrown that is, the governments that his organization had showered with praise, just weeks before, were to blame. What explanation do the economic commentators and

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

pundits offer for this crisis? Essentially, they have none. In a rather revealing statement, published on February 21, the economics editor of The Australian, Alan Wood, admitted that nobody had anticipated the magnitude or the rapid transmission of the crisis. Even after the financial contagion had spread from Thailand across East Asia, no one anticipated the sheer size of the currency falls or the extent of the bank and corporate insolvency that followed. And, in the most significant admission of all, Wood continued: Nothing in orthodox economic theory or in the expectations of financial markets themselves explains the extent of the fall in Asias currencies. [The Australian, February 21-22, 1998] Such professions of ignorance are not confined to the media commentators. Let me cite some recent remarks by the well-known Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Paul Krugman. In speech to a Hong Kong meeting convened by Credit Suisse First Boston in March, he declared: Anyone who claims to fully understand the economic disaster that has overtaken Asia proves, by that very certainty, that he doesnt know what he is talking about. ... The truth is that we have never seen anything like this. Of course the country doctors at the IMF and the US Treasury Department are obliged, by the nature of their position, to adopt a reassuring bedside manner as they prescribe their bitter economic medicine. But we all know that in reality they are pretending a confidence they do not at all feel, that even as they lay down the law to their clients they are groping frantically for models and metaphors to make sense of this thing. In fact, the best thing I can say about the people running the show in this case who happen to be people I know rather well is that they are smart enough, and also personally secure enough, to know and admit it to themselves that they are making it up as they go along. In other words, bourgeois economic theor y is completely unable to explain one of the biggest changes in world economy in the recent period. The reason does not lie in the capacity or incapacity of individual economists. Rather, it is rooted in the very foundations of bourgeois economic theor y itself a theoretical system directed not to revealing the fundamental laws of the capitalist mode of production, but at proving that this is the only viable and rational social system. The underlying premise of all bourgeois economic theory is 4

that capitalism is permanent, like Nature. Consequently, it is unable to develop a scientific explanation for crises, for that would mean admitting there were contradictions within the capitalist economy that produced them. Such an admission would call into question the viability of the whole economic order. The high priests of bourgeois economics treat crises as aberrations, accidents, the results of wrong policy decisions, slack regulation and so on the punishment of the market inflicted on fallible human beings who failed to obey her commands, just as the priestly caste of the feudal order ascribed natural disasters as punishments for transgressing the will of God. The admissions of ignorance, and the general bewilderment of the economics profession, recall what took place in the 1930s, when, contrary to all the textbook analyses showing the smooth workings of the market, the impossible happened and the world economy collapsed. The recent events are not dissimilar, for the growth of the Asian economies has been held up in recent years as a demonstration of the power of the market and the viability of capitalism. In contrast to the method of bourgeois economics, which deals with isolated events, the method of Marxism is above all historical. That is, it seeks to reveal the fundamental laws which govern economic processes and locates the source of crises not in external factors but in the inner contradictions of the capitalist economy which drive it forward. The Asian miracle itself cannot be understood if it is considered in isolation. The rapid growth of the so-called Asia tigers did not represent the opening up of some new road for capitalism but was rather the expression of its deep-seated crisis. In 1973-74, the great post-war expansion of capitalism referred to by some writers as a golden age came to an end. The collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971, the subsequent currency turmoil, the quadrupling of oil prices and the onset of recession were all indications that, after 25 years of expanding markets and profits, a new period of falling profits was being ushered in. Corporations responded to this transformed economic climate by seeking to establish new production methods and acquire cheaper resources and labor in order to lower their costs. This was the origin of the turn to investment in Asia.

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

In the 1960s and early 1970s this process began with offshore manufacturing of components, particularly in the emerging electronics and computer industries. In the 1980s, developments in transport, communications, finances and computer-based technologies opened the way for the development of globalized production methods, with further significant cost savings. Changes in the alignment of international currencies also contributed to the expansion of investment in East Asia. In the early 1980s, under the direction of US Federal Reser ve chairman Paul Volcker, the Reagan administration implemented a high interest policy to squeeze inflation out of the system. It was an initiative undertaken by the dominant sections of finance capital to redress the situation where inflation rates were so high that real bank interest rates were negative. However this program, which saw interest rates in the US go as high as 20 percent, had a number of side effects. As interest rates climbed, so too did the value of the US dollar, leading to expanding US trade deficits. In 1985, the US insisted on a major currency realignment. Under the so-called Plaza agreement, it was decided that the dollar would fall, relative to the Japanese yen. The value of the yen was increased from 250 to the dollar to around 120, resulting in great pressure on Japanese firms competing for a share of the US market. Consequently Japanese capital moved offshore to invest in Southeast Asia and to set up production networks in that region. But towards the end of 1994 further changes took place in the economic environment which were to have farreaching consequences. The devaluation of the Chinese currency by around 50 percent meant that expor ts from China were increasingly competitive in world markets. Chinese production sites, especially in the south, were more attractive. Investment began to shift from the cheap labor

areas of East Asia to the even cheaper labor regions of China. Fur thermore, there were signs of growing overcapacity in a number of key industries. Overinvestment in Asia saw the prices of computer chips fall by 80 percent in 1996. Capacity in the car industry expanded so rapidly that in 1997 it was estimated that if the entire North American industry were shut down there would still be sufficient capacity to meet world demand. At present, the car industry is said to be operating with 15-20 percent overcapacity. This excess is concentrated in Asia, where overcapacity is running at 40 percent. These growing problems were compounded by shifts in currency values. In the (northern) spring of 1995, the US dollar hit its lowest level of 80 yen. After warnings from Japan that further depreciation would lead to a selloff of Japanese holdings of US Treasury notes and bonds, the value of the US dollar was pushed up. By the middle of 1997 it had appreciated from 80 to 125 yen a rise of 56 percent. As a consequence, the East Asian currencies, tied to the US dollar, appreciated as well. Coming on top of the fall in the value of the Chinese currency this meant that the East Asian economies were no longer as competitive as they had been in the early 1990s. Export growth, which had averaged 20 percent in 1994 and 1995, fell to only 5 percent in 1996. Malaysia, South Korea and Thailand ran up current account deficits of between 5 and 8 percent of Gross Domestic Product. On top of these problems came the continued stagnation in Japan, where 30 percent of Southeast Asian exports find their market. The balance of payments gap of the East Asian countries began to widen and shortterm debts increased. The stage was set for the speculative outflows of capital that triggered the crisis from July 1997.

Deflation and the Asian Crisis

As the crisis accelerated towards the end of 1997, it became clear, even to bourgeois economists and media pundits, that something more than a crisis of credit or financial mismanagement was involved. The international financier George Soros, for example, wrote a comment in the London-based Financial Times on December 31, 1997, warning that the financial crisis was far more serious than he had believed. What had 5 started out as a minor imbalance was threatening to become a much bigger one, involving international credit and trade. Soros said the world was on the brink of global deflation that is the depreciation of prices, profits and asset values. On January 15, 1998 the Labor Secretary in the first Clinton administration, Rober t Reich, echoed these warnings, also in a comment published by the Financial

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

Times. Reich said the world had entered a similar period to the late 1920s, when sales of houses, cars and consumer durables declined and industrial production fell. Todays downturn had started before the crisis of the Asian currencies and was developing worldwide. Asia was hit by bankruptcies and bank collapses; demand was falling in Latin America; stagnation and unemployment prevailed in Europe. Only in the United States was demand expanding, but largely financed by consumer debt, which was rapidly approaching its limit. Since then there have been a spate of such comments. The economics correspondent of the Financial Times, commenting on the February 21-22 meeting of the G-7 central bankers and finance ministers in London, noted that while the participants gave an appearance of calm, like swans on a fast flowing stream, underneath they were all paddling frantically. The question is whether they were doing enough to avoid the deflationar y water fall downstream. These warnings form par t of a series of critical publications in the recent times, pointing to the dangers to the world capitalist order arising from overcapacity in industrial production, and the related impact of technological innovation. These warnings have not been made by opponents of capitalism, but its supporters, who fear that the present course of events is leading to an economic breakdown and social upheaval. One well-known example is the book by American journalist William Greider, entitled One World Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism, published one year ago. Greiders basic thesis is that the very productivity of global capitalism has created overcapacity in key sectors of industry, and the constant elimination of jobs through downsizing and the introduction of new technologies is eroding the market for the goods produced by the more productive industries. Accordingly, there is a threat that accumulating overcapacity will lead to some sort of decisive breakdown,

a financial crisis or an implosion of global commerce, perhaps precipitated by emergency measures enacted by nations desperate to protect their home producers. In the 1920s, similar imbalances developed from similar causes, and the root cause of the eventual market breakdown was excess supply and inadequate demand. [William Greider, One World Ready or Not: The Manic Logic of Global Capitalism, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1997, p. 104] Greiders analysis has come under attack in various publications. One of the most vociferous opponents of what he calls the doctrine of global glut is Paul Krugman. Krugman insists that the Greider thesis is invalid on two grounds. Firstly, he argues, if productivity increases in one sector of the economy, this will see a change in relative prices, leading to a clearing of the market and secondly, even if technology does reduce jobs in one sector, it will create jobs in others. Summing up his argument, he writes: Finally, lurking behind the global glut argument may be a very old fallacy about the relationship between consumption and investment. One thing capitalistic economies do is to accumulate capital. That is, not all of their productive capacity is used to produce consumption goods; some of it is used to produce capital goods that will expand future productive capacity. But then not all of that future capacity will be used to satisfy consumers some of it will be used to expand capacity even more, and so on. Now it is very easy, if one puts it that way, to start to think of the whole thing as a sort of chain letter or Ponzi game: surely, you may imagine, at some point this business of building machines to build machines must come to an end with disastrous results. (Something like this seems to be what Greider has in mind when he talks of the manic logic of capitalism.) But in fact as even Karl Marx could have told you there is nothing wrong or unsustainable about an ever-growing capital stock in an ever-growing economy. It has worked for the last 50 years, and there is no obvious end in sight. [Paul Kr ugman, Is Capitalism Too Productive, Foreign Affairs, October-November 1997]

The Contradictions of Capitalism

Contrary to the picture of harmonious development that Krugman attempts to paint, Marx drew out that even if one assumed that all capitalist firms were able to find markets for their commodities, and even if there were no dispropor tions created by the anarchic and blind 6 workings of the market, there were, never theless, inherent contradictions in the process of capitalist accumulation itself. These contradictions inevitably lead to recurring crises, which demonstrate that capitalism is not an eternal mode of production, but is destined to pass

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

into history along with its predecessors. The contradictions Marx uncovered lie in the very hear t of the capitalist system the process of accumulation, correctly enough identified by Krugman as capitalisms driving force. The essence of the capitalist mode of production and this is the source of its dynamism as compared to its predecessors is that production is carried out not for use, but for profit the accumulation, not of material wealth as such, but surplus value. The source of this surplus value is the labor power of the working class, consumed in the production process. The value of the commodity the worker sells to the capitalist in the wage contract, labor power, is vastly different from the value the worker produces in the course of the working day. For example, the wages a car worker receives each day bear no relation to the value he adds to the raw materials and machiner y used up in the production of a car. This additional, or surplus, value, appropriated by capital in the form of profit, provides the basis for the continued accumulation of capital. That is, profits are reinvested in capital equipment and new technology, which are used to extract more surplus value from the working class. The question arises: Can this process go on indefinitely, as the defenders of capitalism such as Krugman maintain, or does the process itself contain objective contradictions, which necessarily assert themselves? Marxs analysis reveals that the root of the crisis is not the underconsumption of the working class, resulting from the fact that it is paid in wages less than it produces, for such a situation is a permanent condition of capitalism. The fundamental fallacy of the arguments advanced by reform-minded critics of capitalism such as Greider is that the conditions to which they point the way productivity

outstrips the consumption of the working masses, and the elimination of jobs through new technologies operate in both boom and slump. They cannot, therefore, be invoked to explain a crisis. The inherent contradictions in the accumulation process lie not in the underconsumption of the working masses or in technology, but in the social relations of production based on the buying and selling of wage labor and the accumulation of private profit. The sole source of surplus value, and profit, is the living labor power of the working class. It provides the life-blood for the expansion of capital. This process contains a contradiction. As the accumulation of capital proceeds, the living labor power of the working class has to expand a larger and larger mass of capital. Therefore, there is an inherent tendency for the rate of profit that is, the ratio of surplus value to the total mass of capital to decline. The emergence of falling profit rates the overaccumulation of capital relative to surplus value, or, to put in another way, the underproduction of surplus value relative to capital induces two processes. Firstly, it brings a ferocious war between the different sections of capital to eliminate one another, leaving a greater share of surplus value for the survivors. This war is known as competition, the struggle in the market. In other words, the rate of profit can be lifted if the competing claims on the available pool of surplus value are reduced. Secondly, profit rates can be restored if the available mass of surplus value is increased through the development of new production technologies that increase the surplus value extracted from the working class in the production process. With these theoretical considerations in mind, let us turn back to an examination of the Asian crisis.

The Falling Profit Rate and the Asian Crisis

As we saw previously, the so-called Asian miracle had its origins in the crisis of capitalism that erupted in the 1970s as the profit rate declined. For a time, the cheap labor resources of this region did enable capital, at least to some extent, to counteract this tendency. The East Asian economies grew and their expansion was held up by the defenders of capitalism as proof of its viability, even as the social conditions of the working class worsened in 7 the advanced capitalist countries. [It needs to be recalled in this context that real wages in the United States, for example, have undergone a continuous decline since 1973, while in Europe there have been no additional jobs created since the mid 1970s. In Australia a detailed report just published shows that poverty levels have increased markedly over the past 25 years.] The crisis of the Asian economies, marked by

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

overinvestment, excess capacity, financial breakdown and a vicious struggle for markets, signifies that the tendency of the rate of profit to decline on a world scale the tendency which led to the rise of the Asian miracle has re-emerged. In other words, if the crisis of the capitalist system as a whole has expressed itself in the tiger economies of Asia, it is precisely because this region was the focus of economic activity aimed at trying to overcome it. Falling profit rates are always expressed in overcapacity and the consequent ruthless struggle between different sections of capital to eliminate each other. As Marx explained so well, one capitalist kills many. This fratricidal struggle finds its expression, not only in competition in the market, but in the demand by the dominant sections of capital that all those measures implemented by national governments to protect its weaker brethren be torn down. This lies at the heart of the International Monetary Fund agenda in the Asian crisis. The critics of the IMF point out that when the crisis erupted, the IMF did not set about re-organising the debts of the Asian economies, as had been done in previous crises, but demanded nothing less than a restructuring of the entire economy. One of these critics, the Harvard economist Martin Feldstein, writing in the latest issue of the US journal Foreign Affairs on the Korean situation, points out that since Koreas foreign debt was only about 30 percent of GDP, and the current account deficit was small and shrinking, the Korean problems were a reflection of a temporary lack of liquidity, rather than insolvency. Short-term action was required to restructure bank debt, along the lines of measures taken in Latin America in 1982. The export capacity of the Korean economy, he insists, would have made such a program eminently realizable. Instead, the IMF organized a pool of $57 billion [the largest such bailout in history NB] from official sources the IMF, the World Bank, the US and Japanese governments, and others to lend to Korea so that its private corporate borrowers could meet their foreign currency obligations to US, Japanese, and European banks. In exchange for these funds, the IMF demanded a fundamental overhaul of the Korean economy and a contractionary policy of higher taxes, reduced spending, and high interest rates. [Martin Feldstein, Refocussing 8

The IMF, Foreign Affairs, March-April 1998] The overhaul of the Korean economy amounted to the elimination of all measures through which Koreanowned capital had protected itself from its more powerful international rivals. The IMF demanded that foreign investors be free to own majority shares in Korean businesses; that financial markets be opened up to foreign banks and insurance companies; and that restrictions be lifted on the import of some industrial products. It also demanded the repeal of labor laws that impeded mass sackings by major corporations. In other words, the IMF had two objectives: to wipe out whole sections of Korean-based capital through the imposition of high interest rate contractionary policies, and to open up profitable areas of the economy to penetration by foreign capital, desperately scouring the globe for new sources of profit. [An article published in the December 22 edition of the New York Times likened the situation to the collapse of the East European Stalinist regimes. That is, the Asian capitalists were being forced to remove their economic Berlin Walls to remain in the globalization process.] Feldstein is highly critical of the IMFs action declaring that: The legitimate political institutions of the country should determine the nations economic structure and the nature of its institutions. A nations desperate need for short-term financial help does not give the IMF the moral right to substitute its technical judgments for the outcomes of the nations political process. Of course, morality has nothing to do with it. The shift in the IMFs response arises, not from the moral outlook of its officials, but the changing demands of finance capital. The re-emergence of falling profit rates has made it urgent, so far as the dominant sections of capital are concerned, to batter down all national-based protective measures. Such measures to ensure weaker sections of capital can appropriate a greater share of surplus value than would otherwise be the case. Protectionist measures can be tolerated so long as the mass of surplus value, available for distribution as profit, expands. But once the situation turns, and surplus value stagnates or even declines, the demand is raised for the abolition of these measures. Their proponents are branded as economic irrationalists, practitioners of crony capitalism, con men and worse. The new IMF agendas clearest expression is in Indonesia. Former US secretary of state, Henry Kissinger,

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

pointed to some of the issues in a recent speech at the Brookings Institute. If the definition of a revolution is fundamental change in the economic and political system, he said, then what we are trying to engineer in some of these countries is clearly a revolution. This revolution is dictated by international finance capital. Its program is set out in the memorandum of economic and financial policies Suhar to signed on January 15 in return for the commitment of $43 billion from the IMF. The document contains about 80 key policy changes. The overall effect is to virtually eliminate the capacity of the national government to effect economic decisions, thereby ensuring that the Indonesian economy is subordinated to the world market and the global movement of capital. Among the measures in the document are: a budget deficit target at 1 percent of GDP; a list of subsidies to be eliminated, and when; cancellation of 12 major infrastructure projects; establishment of a central bank on an autonomous basis, with responsibility for setting interest rates according to an inflation target; four state banks to be privatized; a level playing field for foreign investors; liberalization of rules governing trade and foreign investment; elimination of import monopolies; new rules for competition in cement; a campaign to deregulate and privatize the economy in order to promote domestic competition and expand the scope of the private sector; abolition of all monopoly marketing organizations; complete deregulation of internal agricultural trade; the abolition of the Clove Marketing Board. These are just

some of the IMFs conditions. The dramatic reorientation in the IMF program, from the early 1980s to the late 1990s this revolution, as it has been dubbed is the policy expression of the changed objective situation in which world capitalism finds itself. In the 1980s and early 1990s, as the expansion of Asianbased production eased the pressure on profit rates, finance capital was able to tolerate the various measures implemented by national governments to protect their socalled crony capitalists and the national bourgeoisie, even as they opened up the economy to penetration by transnational corporations. In these conditions, the IMF found no difficulty in carrying out the closest collaboration with the chaebols in Korea, the Suharto family monopolies in Indonesia, or the military and their businesses in Thailand. But now that the accumulation of capital itself has led to the re-emergence of falling profits, these restrictions have become intolerable. Thus the IMFs program has not been to resolve the currency and financial crisis, along the lines carried out in the past, but rather to utilize the crisis to push through its new agenda. This agenda is not confined to East Asia. In his article on Korea, for example, Feldstein says that the specific measures that the IMF insists must be changed are not so different from those in the major countries of Europe. Or as the international editor of The Australian, Paul Kelly commented on the Indonesian program: It reflects a specification of detail that Australia and most nations would have trouble meeting.

Growing Inter-imperialist Antagonisms

The increasingly vicious global struggle for markets goes beyond the East Asian crisis. It can be seen in the mounting antagonisms between the major capitalist powers. These tensions were reflected in a recent comment by James K. Glassman, published in the Washington Post under the title Get Tough With Japan, subsequently made the basis for an editorial in that newspaper. Glassman says the problem in Asia is not Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea it is Japan. Japan is the villain. Japan could be the hero. But, for inexplicable reasons, US policymakers dont want to lean hard on Japan to change its wretched fiscal and financial 9 policies. Its time to stop being polite and get tough. He demands an end to the system of command-and-control capitalism practised by the Japanese government. [Washington Post, March 3, 1998] These are not isolated views. Business Week published a similar editorial under the headline Japan needs to face the music now. The editorial denounced Japan for denying its economic malaise, and then set out its agenda: What may be holding back Japan the most is an obsession with the care and feeding of its aging population. The same centralized, bureaucratically run system designed to concentrate and funnel savings into production is now channeling it into retirement. Tokyo is

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

raising taxes to get its fiscal house in order and is dragging its feet on deregulation for fear of unleashing costly unemployment on its older workers. Japan was not the magazines only target. Another editorial said that with the creation of the euro next year a new international reserve currency would begin to challenge the US dollar, while a third editorial launched an attack on France under the title When Will France Give Up Karl Marx? The social and political climate in France is hostile to anyone who wants to make a profit. Company owners

are perceived as rapacious capitalists who should be taxed aggressively to be kept under control and prevented from doing ill to society. [Business Week, March 9, 1998] In an earlier time, such views would have been regarded as eccentric, even outlandish. The fact that they are now published so openly within leading bourgeois publications is an expression of the program of capital itself: the market and the drive for profit must dominate, unrestricted by national regulations, concerns for jobs, the care of the aged or any other considerations.

Capitalism out of Control

Throughout this lecture we have sought to demonstrate that to speak of an Asian crisis is misleading. In 1883 a volcanic eruption destroyed the island of Krakatoa in the Indonesian archipelago. The event took place in Indonesia, but its causes lay deep within the core of the earth. The devastation being inflicted upon hundreds of millions of workers in East Asia is the outcome of global processes that can, and will, erupt anywhere. Let me illustrate this point by referring to a recent article by the economist David Hale, a frequently quoted media commentator. He explains that with a rapid reduction in the cost of global capital transactions and an enormous expansion of funds one major source being workers pension funds great quantities of funds are moving around the world in search of profits. Consequently, the Mexican crisis of 1995 and the Asian crisis of 1997 are not freakish phenomena resulting from bad policy or accidents. They are the natural byproduct of a financial system in which global capital flows are expanding rapidly and in which investor sentiment is constantly changing in response to economic and political information. This extreme volatility is not just a consequence of the vast quantities of finance capital. It is, above all, an expression of the pressure on the rate of profit. In these conditions, each section of capital has to try to stay ahead of the wave. It cannot be content with receiving a rate of return on long-term investments these are much too low. It must be continually on the move in search of profitable outlets. The last one out of a collapsing region will be bankrupted. Once a movement starts, it has the tendency to turn into a stampede. All sorts of factors 10 combine to play a role political considerations, psychology, rumors etc. but the economic factor is the global crisis of profits. In other words, it is not a question of waiting until the storm in Asia blows over and then getting back to normal. The crisis that has erupted over the past nine months and deepening daily has become the norm. The US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan admitted as much at a recent bankers conference in Miami. He described the situation in East Asia as follows: Uncertainty and retrenchment have escalated. The state of confidence so necessary to the functioning of any economy has been torn asunder. Some exchange rates have fallen to levels that are understandable only in the context of a veritable collapse of confidence in the functioning of an economy. And what of the future? Greenspan assured his audience that slowly but surely understanding was developing as to how the new high-tech international financial system was functioning and that hopefully before we run into crisis number three and there will be a crisis number three well have suf ficient preventative measures in place either to fend it off, or if it occurs, to assuage its severity. Where will crisis number three strike? A crisis on Wall Street perhaps? It would bankrupt tens of millions of people who have been forced to place their savings in mutual funds and stock market shares to try to provide for the health and education of their children, and their own retirement. Or perhaps the collapse of the Australian dollar and stockmarket, where 40 percent of workers have funds invested, either directly or via superannuation. Or perhaps a crisis will erupt when the single European

The Asian Meltdown: A Crisis of Global Capitalism

1998 World Socialist Web Site www.wsws.org

currency, the euro, is launched next year. Alternatively, it may be triggered in China, either from the growth of mass unemployment, as state enterprises are slashed, or a devaluation of the currency. It could also arise from a collapse of a bank or chaebol in Korea or a series of bankruptcies and bank collapses in Japan ... and the list goes on. The world economy resembles a minefield. The slightest disturbance can set off a series of explosions. The picture presented by Greenspan is tr uly astounding. Primitive man huddled in fear before the forces of Nature which he could neither understand nor

control. To him they were gods to whom he made sacrifices in the hope they would be assuaged and spare him the terrible consequences of their actions. Today we find the head of the US Federal Reserve Board the most powerful financial figure in the world telling us he is confronted by forces that he neither understands nor controls, but expressing the hope that perhaps these gods too may be assuaged provided that working people all over the world make sufficient sacrifices in terms of their jobs, wages and social conditions to meet the dictates of the markets.

Working Class Requires a Global Program

The vast accumulations of capital moving around the world leaving disaster in their wake are not products of God or Nature. They are the accumulated savings of millions of people. The days are long gone when business was financed out of the resources of individual capitalists. The capital moving around the world is the financial expression of the resources created by the collective labor, intelligence and ingenuity of hundreds of millions of people. Why is this vast wealth not utilized as a means for the advancement of human welfare, but instead for the imposition of untold misery? The answer lies in the fact that it is not subject to the conscious control and regulation of society as a whole the producers who created it but subordinated to the profit system. In other words, the problem confronting mankind lies in the fact that the productive forces the wealth created by workers all over the world have outgrown the social relations based on private ownership, private profit and the nation-state, within which they have developed. Unprecedented developments of technology have brought about the globalization of the productive forces. But this process has intensified the contradiction between the world economy and the nation-state system of capitalism. The increasing conflicts between the major capitalist powers for markets, profits, spheres of influence, are the sure signs that all the conditions which led to two world wars this century are maturing once again. What program must be developed to meet this crisis? The answer does not lie in the call advanced by the unholy alliance of radicals, one-time lefts, nationalists and outright fascists for the strengthening of the national state to curb the operations of global capital. The nation-state is at the heart of the problem. The vast movements of capital on a global scale, the integration of all aspects of finance and production, reflect the reality that mans productive activity has outgrown the narrow confines of the national state. It has become as obsolete today as the feudal principalities that it replaced some 200 years ago. The task is not to try and force the productive forces back into the national straitjacket. Rather, it is to establish new social relations within which the productive forces can be accommodated and developed for the benefit of all. The market, whose blindly working laws reflect the str uggle between dif ferent sections of capital to appropriate the surplus value extracted from the working class, must be overturned. A consciously planned socialist economy must be established on an international scale. That is the program fought for by the world party of the socialist revolution, the International Committee of the Fourth International.

To contact the International Committee of the Fourth International

E-mail: icfi@wsws.org

United States: Socialist Equality Party, PO Box 48377, Oak Park, MI 48237 USA Telephone 248 967 2924 Australia: Socialist Equality Party, PO Box 367, Bankstown, Sydney, NSW Australia 2200 Telephone 61 2 9790 3511 Britain: Socialist Equality Party, PO Box 1306, Sheffield S9 3 UW England Telephone 114 244 0055 Germany: Partei fr Soziale Gleichheit, Postfach 100 105, D-45001 Essen Telefon 0201 87 01 30

11

You might also like

- Summary: Stephen Roach on the Next Asia: Review and Analysis of Stephen S. Roach's BookFrom EverandSummary: Stephen Roach on the Next Asia: Review and Analysis of Stephen S. Roach's BookNo ratings yet

- Business Cycle Macroeconomic Gross Domestic Product Capacity Utilization Inflation Bankruptcies Unemployment RateDocument5 pagesBusiness Cycle Macroeconomic Gross Domestic Product Capacity Utilization Inflation Bankruptcies Unemployment RateRajesh MatnaniNo ratings yet

- Global Financial Crisis: IndonesiaDocument30 pagesGlobal Financial Crisis: IndonesiaPagla HawaNo ratings yet

- May Allah S.W.T Guide Us Through This Financial Crisis.: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Fakulti Undang-UndangDocument21 pagesMay Allah S.W.T Guide Us Through This Financial Crisis.: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Fakulti Undang-Undangmusbri mohamedNo ratings yet

- Japan’s 2011 Earthquake & Tsunami: Short & Long Term Economic ImpactDocument5 pagesJapan’s 2011 Earthquake & Tsunami: Short & Long Term Economic ImpactHuma AnsariNo ratings yet

- Learning from the Southeast Asia Crisis: Market Failures and Human SufferingDocument7 pagesLearning from the Southeast Asia Crisis: Market Failures and Human Sufferingrdparikh2323No ratings yet

- The Asian Debt-And-Development Crisis of 1997-?: Causes and ConsequencesDocument24 pagesThe Asian Debt-And-Development Crisis of 1997-?: Causes and ConsequencesMar SebastiánNo ratings yet

- The Pak Banker Mar 29, 2011: World Economies - LahoreDocument5 pagesThe Pak Banker Mar 29, 2011: World Economies - LahoreuranusbbyNo ratings yet

- By Partner - TaskDocument7 pagesBy Partner - TaskCyrisse Mae ObcianaNo ratings yet

- India's Bubble Economy Headed Towards Iceberg?: CategorizedDocument6 pagesIndia's Bubble Economy Headed Towards Iceberg?: CategorizedMonisa AhmadNo ratings yet

- ARI129-2009 Vashisht-Pathak Global Economic Crisis IndiaDocument6 pagesARI129-2009 Vashisht-Pathak Global Economic Crisis IndiaViral ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Vishal Manish M (123PS01629) - IMG CommentryDocument7 pagesVishal Manish M (123PS01629) - IMG Commentryamsavalli.vfNo ratings yet

- JPRI Working Paper NoDocument7 pagesJPRI Working Paper NoJohnNo ratings yet

- Debt-Fueled Growth - Can The West Avoid A Japanese FutureDocument4 pagesDebt-Fueled Growth - Can The West Avoid A Japanese FutureMartin BeckerNo ratings yet

- After Tohoku: Do Investors Face Another Lost Decade From Japan?Document14 pagesAfter Tohoku: Do Investors Face Another Lost Decade From Japan?ideafix12No ratings yet

- The End of the Asian Economic MiracleDocument6 pagesThe End of the Asian Economic MiraclegabrielNo ratings yet

- Global Financial Crisis and The South Korean EconomyDocument25 pagesGlobal Financial Crisis and The South Korean EconomyABHISHEK KUMARNo ratings yet

- Now The Brics Party Is Over, They Must Wind Down The State'S RoleDocument4 pagesNow The Brics Party Is Over, They Must Wind Down The State'S RoleGma BvbNo ratings yet

- Trabajo Colaborativo AsiaDocument12 pagesTrabajo Colaborativo AsiaLeonardo AguirreNo ratings yet

- Global Economic RecessionDocument7 pagesGlobal Economic RecessionstrikerutkarshNo ratings yet

- Japan's Fading Economy: Interim Report on Macroeconomic ChallengesDocument7 pagesJapan's Fading Economy: Interim Report on Macroeconomic ChallengesArpita SenNo ratings yet

- Is East The New WestDocument7 pagesIs East The New WestalokpshahNo ratings yet

- Global Economic Recession & It'S Impact On Indian EconomyDocument2 pagesGlobal Economic Recession & It'S Impact On Indian EconomybhaviniiNo ratings yet

- Actualrseminaepg 3 Rdsem RepairedDocument16 pagesActualrseminaepg 3 Rdsem RepairedanabNo ratings yet

- Japan Economy Final ProjectDocument28 pagesJapan Economy Final ProjectSaurabh TrivediNo ratings yet

- AmericanProspect 1998 TheIMFandtheAsianFlu March-April1998Document8 pagesAmericanProspect 1998 TheIMFandtheAsianFlu March-April1998Abdurrohim NurNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Presentation September 10 2012Document143 pagesRisk Management Presentation September 10 2012George LekatisNo ratings yet

- South Korea - IMF-BOP IssuesDocument6 pagesSouth Korea - IMF-BOP IssuesSarinaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft India The Best Employer: Randstad: What Are The Differences Between Closed Economy and Open Economy ?Document5 pagesMicrosoft India The Best Employer: Randstad: What Are The Differences Between Closed Economy and Open Economy ?Subramanya BhatNo ratings yet

- World Financial Crisis and Its Impact: Group 1Document31 pagesWorld Financial Crisis and Its Impact: Group 1Silentt WordssNo ratings yet

- Martin Wolf examines threats to global recovery from lingering financial fault linesDocument6 pagesMartin Wolf examines threats to global recovery from lingering financial fault linespriyam_22No ratings yet

- CHAP-1 Economic Overview of The JapanDocument20 pagesCHAP-1 Economic Overview of The JapanTushar PanchalNo ratings yet

- Global Financial CrisisDocument15 pagesGlobal Financial CrisisAkash JNo ratings yet

- Elias Bakomichalis.20121001.143201Document2 pagesElias Bakomichalis.20121001.143201anon_859523921No ratings yet

- Impact of Credit Crisis on BRIC CountriesDocument5 pagesImpact of Credit Crisis on BRIC CountriesshebinaluvaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument22 pagesReportlaksh002No ratings yet

- VIETNAM - Ready For Doi Moi II?: SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance No. 286 December 1998Document14 pagesVIETNAM - Ready For Doi Moi II?: SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance No. 286 December 1998tanphongphutuNo ratings yet

- Global CrisisDocument28 pagesGlobal CrisisAli JumaniNo ratings yet

- (Kinh tế vmcs) Khủng hoảng Việt NamDocument22 pages(Kinh tế vmcs) Khủng hoảng Việt NamHaiLinhPhanNo ratings yet

- The Economics of Japan's Lost Decades: December 2012Document28 pagesThe Economics of Japan's Lost Decades: December 2012ianclarksmithNo ratings yet

- Steering Out of The Crisis: Robert WadeDocument8 pagesSteering Out of The Crisis: Robert WadegootliNo ratings yet

- Marx and The Financial Crisis of 2008Document25 pagesMarx and The Financial Crisis of 2008Neil T. LoehleinNo ratings yet

- Asian Financial CrisisDocument5 pagesAsian Financial Crisisapi-574456094No ratings yet

- Vinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalDocument4 pagesVinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalFinterestNo ratings yet

- Global Recession Impact in IndiaDocument5 pagesGlobal Recession Impact in IndiaCharu ModiNo ratings yet

- Lincoln 2002Document23 pagesLincoln 2002JohnNo ratings yet

- Ill Winds From EuropeDocument3 pagesIll Winds From EuropeAbhishek PkNo ratings yet

- Japan's 1990s economic crisisDocument19 pagesJapan's 1990s economic crisisSrinivas ReddyNo ratings yet

- RecessionDocument62 pagesRecessionVandana Insan100% (1)

- Balance Sheet Recession - Richard KooDocument19 pagesBalance Sheet Recession - Richard KooBryan LiNo ratings yet

- South East CrisesDocument6 pagesSouth East CrisesavhadrajuNo ratings yet

- MACRO-143 FinalDocument22 pagesMACRO-143 FinalmahdeeazammahiNo ratings yet

- Key Highlights of Indonesian EconomyDocument11 pagesKey Highlights of Indonesian EconomySiddharth JainNo ratings yet

- Japanese Economy ThesisDocument5 pagesJapanese Economy Thesislyjtpnxff100% (1)

- Financial Crisis in East Asia: A Macroeconomic Perspective: Bakul H DholakiaDocument14 pagesFinancial Crisis in East Asia: A Macroeconomic Perspective: Bakul H DholakiaravidraoNo ratings yet

- Global Economic RecoveryDocument13 pagesGlobal Economic RecoveryvilasshenoyNo ratings yet

- Federal Trade Commission.20121030.163248Document2 pagesFederal Trade Commission.20121030.163248anon_115138551No ratings yet

- Global Economy Faces New Normal ChallengesDocument89 pagesGlobal Economy Faces New Normal ChallengesMiltonThitswaloNo ratings yet

- 세계투기거품 연구 (IMF,2008)Document77 pages세계투기거품 연구 (IMF,2008)revolutin010No ratings yet

- Globalization and GovernanceDocument30 pagesGlobalization and Governancerevolutin010No ratings yet

- Constitution of Global Capitalism S GillDocument20 pagesConstitution of Global Capitalism S GillRoleitorNo ratings yet

- Globalization and State StructurDocument35 pagesGlobalization and State Structurrevolutin010No ratings yet

- Gereffi Et Al - 2005 - Governance of GVCsDocument27 pagesGereffi Et Al - 2005 - Governance of GVCsFlorinNicolaeBarbuNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument1 pageCase Studytaan100% (1)

- Module 4-Operating, Financial, and Total LeverageDocument45 pagesModule 4-Operating, Financial, and Total LeverageAna ValenovaNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 01 ACCOUNTING AND THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENTDocument66 pagesChapter - 01 ACCOUNTING AND THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENTRajesh Arora100% (1)

- Corporate Governance IntroductionDocument34 pagesCorporate Governance IntroductionIndira Thayil100% (2)

- TOWS Matrix: A Strategic Planning and Management ToolDocument3 pagesTOWS Matrix: A Strategic Planning and Management ToolkamalezwanNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 3 Questions Mfrs 15 Revenue From Contracts With Customers - Lazar and HuangDocument4 pagesTutorial 3 Questions Mfrs 15 Revenue From Contracts With Customers - Lazar and Huang--bolabolaNo ratings yet

- AUDIT OF INVESTMENTS - AssociateDocument4 pagesAUDIT OF INVESTMENTS - AssociateJoshua LisingNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy at FPL Group, Inc. (A)Document16 pagesDividend Policy at FPL Group, Inc. (A)Aslan Alp0% (1)

- BMA 12e PPT Ch13 16 PDFDocument68 pagesBMA 12e PPT Ch13 16 PDFLuu ParrondoNo ratings yet

- Pre-Qualification Exam in LawDocument4 pagesPre-Qualification Exam in LawSam MieNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet Component Matching Exercise: Strictly ConfidentialDocument6 pagesBalance Sheet Component Matching Exercise: Strictly Confidentialanjali shilpa kajalNo ratings yet

- 25 CFR Part 20 Regulations PDF FormatDocument41 pages25 CFR Part 20 Regulations PDF FormatacooninNo ratings yet

- Case 2Document21 pagesCase 2Nathalie PadillaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Handout Solution - Accounting 405-1Document5 pagesChapter 7 Handout Solution - Accounting 405-1Bridget ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Income Statement TutorialDocument5 pagesIncome Statement TutorialKhiren MenonNo ratings yet

- A Great Valuation Play Where Commodity Business Is A Cash CowDocument29 pagesA Great Valuation Play Where Commodity Business Is A Cash Cowgullapalli123No ratings yet

- Here Is Why He FiledDocument83 pagesHere Is Why He FileddiannedawnNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Objective QuestionsDocument70 pagesStrategic Management Objective QuestionsJose Sebastian50% (2)

- GDP Measures Investment, Income and ExpenditureDocument9 pagesGDP Measures Investment, Income and ExpenditurePranta SahaNo ratings yet

- Lic PPT FMSDocument56 pagesLic PPT FMSRam Kishen KinkerNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 1 - Prepare Budgets Case Study - Houzit: BSBFIM601 Manage FinancesDocument2 pagesAssessment Task 1 - Prepare Budgets Case Study - Houzit: BSBFIM601 Manage FinancesMemay MethaweeNo ratings yet

- Grade 11, Accounting, Chapter 3 Recording of Transaction IDocument75 pagesGrade 11, Accounting, Chapter 3 Recording of Transaction Ihum_tara1235563100% (1)

- BUS 525: Managerial Economics: Pricing Strategies For Firms With Market PowerDocument45 pagesBUS 525: Managerial Economics: Pricing Strategies For Firms With Market PowerNavid Al GalibNo ratings yet

- Governmental and Nonprofit Accounting EnvironmentDocument6 pagesGovernmental and Nonprofit Accounting EnvironmentAnonymous XIwe3KK67% (3)

- Csec Poa January 2014 p2Document13 pagesCsec Poa January 2014 p2Renelle RampersadNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting A Managerial Perspective PDFDocument3 pagesFinancial Accounting A Managerial Perspective PDFVijay Phani Kumar10% (10)

- M6 - Deductions P2 Students'Document53 pagesM6 - Deductions P2 Students'micaella pasionNo ratings yet

- Chapter Wise Question BankDocument227 pagesChapter Wise Question Bankvishal sacharNo ratings yet

- Comparative Analysis and Cash Flow Statements of Hul & Itc: - Group A2Document11 pagesComparative Analysis and Cash Flow Statements of Hul & Itc: - Group A2DEBANGEE ROYNo ratings yet

- McKinsey Crack A CaseDocument28 pagesMcKinsey Crack A CaseRajat Mathur100% (7)