Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Digests

Uploaded by

Dick ButtkissCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Digests

Uploaded by

Dick ButtkissCopyright:

Available Formats

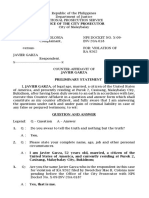

G.R. No. L-35989 October 28, 1977 FERMIN JALOVER, petitioner, vs.

PORFERIO YTORIAGA, CONSOLACION LOPEZ and HON. VENICIO ESCOLIN, in his capacity as Presiding Judge, Branch V, Court of First Instance of Iloilo, respondents. Facts: Sometime in April, 1960, private respondents Porferio Ytoriaga and Consolacion Lopez filed against Ana Hedriana and petitioner Fermin Jalover a complaint in the CFI of Iloilo. The action involves the possession and ownership of an accreted land. Respondents prayed that they be declared the owners of the increased portion of land and petitioners to vacate the premises and restore possession to the former. The case was set for trial. On September 4, 1963, private respondents, formally offered documentary evidence, and upon the admission thereof, they rested their case. (PLS. TAKE NOTE) Whereupon, continuation of trial was ordered transferred until further assignment. Trial was postponed many times stretching to a period of more than 6 years, until January 26, 1970, when the case was called for trial, and the Presiding Judge dismissed the case, for failure of private respondents to appear in court, in an order which reads: The complaint was filed on April 6, 1960 up to the present the trial of the case has not been finished. The counsel of record for the plaintiff is Atty. Amado Atol who since several years ago has been appointed Chief of the Secret Service of the Iloilo City Police Department. Plaintiff did not take the necessary steps to engage the service of another lawyer in lieu of Atty. Atol. Two years later, private respondents' lawyer, Atty. Amado B. Atol, filed an MR of the order dismissing the case. Atty. Atol alleged that the said respondents did not fail to prosecute because, during the times that the case was set for hearing, at least one of said respondents was always present, and the record would show that the transfers of hearing were all made at the instance of petitioner or his counsel; and, moreover, private respondents had already finished presenting their evidence. Petitioner opposed the motion on the ground that the order of dismissal issued two years before was an adjudication on the merits and had long become final. Respondent Judge denied the MR on the ground that the order of dismissal had become final long ago and was beyond the court's power to amend or change. Private respondents then filed a Petition for Relief from Judgment. The petition for relief was given due course, and respondent Judge set aside the order of dismissal by the CFI, and setting the continuation of the trial for September 15, 1972. The reasons stated by respondent Judge in support are: 1. While respondent Porferio Ytoriaga was furnished with a copy of the dismissal order, his counsel, Atty. Atol, was never served with a copy thereof, hence,

pursuant to the settled rule that where a party appears by attorney, a notice to the client and not to his attorney is not a notice of law, the said order of dismissal never became final; and (PLS. TAKE NOTE) 2. The order of dismissal was without legal basis, considering that private respondents had already presented their evidence and rested their case on September 4, 1963, and the hearing scheduled for January 26, 1970 was for reception of petitioner's evidence; Petitioner moved for reconsideration but was denied. Hence, the present special civil action. Issue: Whether the case has long become final and executory. Held: No. Order of Dismissal served to respondents, not to their counsel of record.

It is uncontroverted that the order dismissing the case for private respondents' "failure to Prosecute," was served upon private respondents themselves, and not upon their as attorney of record, Atty. Amado B. Atol, and that there was no court order directing that the court's processes, particularly the order of dismissal should be served directly upon private respondents. It is settled that when a party is represented by counsel, notice should be made upon the counsel, and notice upon the party himself is not considered notice in law unless service upon the party is ordered by the court. The term "every written notice" used in Section 2 of Rule 13 includes notice of decisions or orders. Private respondents' counsel of record not having been served with notice of the order dismissing the case, the said order did not become final. It will also be noted that, as found by respondent Judge, private respondents adduced their evidence and rested their case on September 4, 1963, or more than six years before the dismissal of the case. It was, therefore, the turn of petitioner, as defendant, to present his evidence.

Respondents absence at the hearing waived only right to cross-examine and not Failure to Prosecute.

In the premises, private respondents could not possibly have failed to prosecute they were already past the stage where they could still be charged with such failure. As correctly held by respondent Judge, private respondents' absence at the hearing scheduled on January 6, 1970 "can only be construed as a waiver on their part to cross-examine the witnesses that defendants might present at the continuation of trial and to object to the admissibility of the latter's evidence." The right to cross-examine petitioner's witnesses and/or object to his evidence is a right that belongs to private respondents which they can certainly waive. Such waiver could be nothing more than the "intentional relinquishment of a known right," and as such, should not have beer taken against private respondents. To dismiss the case after private respondents had submitted their evidence and rested their case, would not only be to hold said respondents accountable for waiving a right, but also to deny them one of the cardinal primary rights of a litigant, which is,

corollary to the right to adduce evidence, the right to have the said evidence considered by the court. The dismissal of the case for failure to prosecute, when in truth private respondents had already presented their evidence and rested their case, and, therefore, had duly ,prosecuted their case, would in effect mean a total disregard by the court of evidence presented by a party in the regular course of trial and now forming part of the record.

The ends of justice would be better served if, in its deliberative function, the court would consider the said evidence together with the evidence to be adduced by petitioner. Petition for relief from judgment A petition for relief is available only if the judgment or order complained of has already become final and executory; but here, as earlier noted, the order of dismissal never attained finality for the reason that notice thereof was not served upon private respondents' counsel of record. The petition for relief may nevertheless be considered as a second motion for reconsideration or a motion for new trial based on fraud and lack of procedural due process.

You might also like

- CIVPRO Batch 5 Case DigestsDocument19 pagesCIVPRO Batch 5 Case DigestsVic RabayaNo ratings yet

- Sacay V DENRDocument2 pagesSacay V DENRJam ZaldivarNo ratings yet

- CivPro Assignment 3Document20 pagesCivPro Assignment 3Janet Dawn AbinesNo ratings yet

- 212 - Chan v. AbayaDocument2 pages212 - Chan v. Abayaanon_614984256No ratings yet

- CA upholds SEC jurisdiction over investment fraud case despite petitioners' prescription claimDocument174 pagesCA upholds SEC jurisdiction over investment fraud case despite petitioners' prescription claimMinnie chanNo ratings yet

- 00 Credit Finals - CasesDocument6 pages00 Credit Finals - CasesJanz SerranoNo ratings yet

- 110 GR - 218269 - 2018 Dumo vs. Republic, G.R. No. 218269, June 6, 2018Document2 pages110 GR - 218269 - 2018 Dumo vs. Republic, G.R. No. 218269, June 6, 2018Earvin Joseph BaraceNo ratings yet

- Oil and Gas Dispute Arbitration RulingDocument2 pagesOil and Gas Dispute Arbitration RulingKiana AbellaNo ratings yet

- Gonzaga v Villanueva: Atty Suspended for Deceit, Unauthorized AppearanceDocument3 pagesGonzaga v Villanueva: Atty Suspended for Deceit, Unauthorized AppearanceLonalyn Avila AcebedoNo ratings yet

- Nicolas Lizares V. Rosendo HernaezDocument20 pagesNicolas Lizares V. Rosendo HernaezGraceNo ratings yet

- Del Mar vs. PagcorDocument30 pagesDel Mar vs. PagcorG Ant MgdNo ratings yet

- Regalian Doctrine and land classificationDocument80 pagesRegalian Doctrine and land classificationAndrea IvanneNo ratings yet

- Lorenzana vs. CayetanoDocument1 pageLorenzana vs. CayetanoRommel Mancenido LagumenNo ratings yet

- Courts in Philippines have jurisdiction over divorce casesDocument5 pagesCourts in Philippines have jurisdiction over divorce casesMargeNo ratings yet

- Tumalad Vs Vicencio, G.R. No. L-30173, September 30, 1971Document3 pagesTumalad Vs Vicencio, G.R. No. L-30173, September 30, 1971Lalj BernabecuNo ratings yet

- Bache & Co (1971)Document20 pagesBache & Co (1971)delayinggratificationNo ratings yet

- Bantay Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesBantay Vs ComelecElmira PagotNo ratings yet

- 13 - Pinga V Heirs of SantiagoDocument2 pages13 - Pinga V Heirs of SantiagoKriselNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Roasa: Possession Prior to Land Classification CountsDocument2 pagesRepublic v. Roasa: Possession Prior to Land Classification CountsRaymond ChengNo ratings yet

- PALMA V CADocument3 pagesPALMA V CAHazel BarbaronaNo ratings yet

- Case Digeeeeeest LaaanzDocument33 pagesCase Digeeeeeest LaaanzJM CamalonNo ratings yet

- MAURICIO C. ULEP vs. THE LEGAL CLINIC Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993Document2 pagesMAURICIO C. ULEP vs. THE LEGAL CLINIC Bar Matter No. 553 June 17, 1993Andy BNo ratings yet

- The Diocese of Bacolod Doctrine of Heirarchy of CourtsDocument2 pagesThe Diocese of Bacolod Doctrine of Heirarchy of CourtsIkkinNo ratings yet

- DepEd's Failure to Prove Ownership Defeats Laches ClaimDocument15 pagesDepEd's Failure to Prove Ownership Defeats Laches ClaimKim EcarmaNo ratings yet

- Crimpro Rule 112 Title Govsca G.R. No. 101837 Date: Feb 11, 1992 Ponente: Romero, J PDocument3 pagesCrimpro Rule 112 Title Govsca G.R. No. 101837 Date: Feb 11, 1992 Ponente: Romero, J PKim Laurente-AlibNo ratings yet

- Dr. Antonio Lizares vs. Caluag 14 Scra 746Document4 pagesDr. Antonio Lizares vs. Caluag 14 Scra 746albemartNo ratings yet

- RUFINO O. ESLAO vs COADocument2 pagesRUFINO O. ESLAO vs COACistron ExonNo ratings yet

- Enriquez v. GimenezDocument1 pageEnriquez v. GimenezMagr EscaNo ratings yet

- Reyes V Lim and Pemberton V de LimaDocument2 pagesReyes V Lim and Pemberton V de LimaCheska Mae Tan-Camins WeeNo ratings yet

- RTC Jurisdiction Over Concubinage CaseDocument1 pageRTC Jurisdiction Over Concubinage CaseCamella AgatepNo ratings yet

- Evidence and Claims Against EstatesDocument5 pagesEvidence and Claims Against EstatesClintNo ratings yet

- Legal Profession - Yu v. Palana AC No. 7747 SC Full TextDocument7 pagesLegal Profession - Yu v. Palana AC No. 7747 SC Full TextJOHAYNIENo ratings yet

- AgencyDocument1 pageAgencyLENNY ANN ESTOPINNo ratings yet

- Case 55 Cervantes Vs Atty SabioDocument3 pagesCase 55 Cervantes Vs Atty SabioLouella ArtatesNo ratings yet

- Santos Vs Crisostomo RevisedDocument2 pagesSantos Vs Crisostomo RevisedMonica B. AsebuqueNo ratings yet

- Natalia Realty, Inc. vs. Department of Agrarian Reform 225 SCRA 278, August 12, 1993Document2 pagesNatalia Realty, Inc. vs. Department of Agrarian Reform 225 SCRA 278, August 12, 1993Susie SotoNo ratings yet

- Republic V Vda de Castellvi DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic V Vda de Castellvi DigestWazzupNo ratings yet

- CASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersDocument2 pagesCASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersAl Jay Mejos100% (1)

- NHA Joint Venture Agreement Ruled ConstitutionalDocument3 pagesNHA Joint Venture Agreement Ruled ConstitutionalZydalgLadyz NeadNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Rules on Attorney's Right to Fees After Client SettlementDocument3 pagesSupreme Court Rules on Attorney's Right to Fees After Client SettlementSam LagoNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Cases - Assignment 1Document211 pagesLegal Ethics Cases - Assignment 1dailydoseoflawNo ratings yet

- 24 Executive Digest - Barrazona vs. RTC of BaguioDocument1 page24 Executive Digest - Barrazona vs. RTC of Baguiolyka timanNo ratings yet

- Ko Vs MaderamenteDocument2 pagesKo Vs MaderamenteAngelica SegueNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure 4Document28 pagesCivil Procedure 4Doreen LabbayNo ratings yet

- Heirs fail to prove title to land in quieting caseDocument2 pagesHeirs fail to prove title to land in quieting caseSeleccíon Coffee100% (1)

- R Transport Corporation vs. Philippine Hawk Transport CorporationDocument2 pagesR Transport Corporation vs. Philippine Hawk Transport CorporationReniel EdaNo ratings yet

- Kiener vs. Atty AmoresDocument3 pagesKiener vs. Atty AmoresPIKACHUCHIE100% (1)

- DelicadezaDocument7 pagesDelicadezaromeo n bartolomeNo ratings yet

- Macapinlac vs. Gutierrez Repide Jose C. Macapinlac, vs. Francisco Gutierrez Repide, Et Al. G.R. No. 18574 September 20, 1922Document2 pagesMacapinlac vs. Gutierrez Repide Jose C. Macapinlac, vs. Francisco Gutierrez Repide, Et Al. G.R. No. 18574 September 20, 1922Joanna May G CNo ratings yet

- Bache and Co. v. RuizDocument2 pagesBache and Co. v. RuizNickoNo ratings yet

- Notarial law requirements for petitionsDocument3 pagesNotarial law requirements for petitionsPaolo JavierNo ratings yet

- Case11 Dalisay Vs Atty Batas Mauricio AC No. 5655Document6 pagesCase11 Dalisay Vs Atty Batas Mauricio AC No. 5655ColenNo ratings yet

- Celestino Balus vs. Saturnino BalusDocument3 pagesCelestino Balus vs. Saturnino BalusDiosa Mae SarillosaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Delfin Vs NHADocument26 pagesHeirs of Delfin Vs NHAMaria Angelica DavidNo ratings yet

- Hizon V CADocument2 pagesHizon V CAKastin SantosNo ratings yet

- Casimiro V TandogDocument1 pageCasimiro V TandogMerryl Kristie FranciaNo ratings yet

- 07 Government Vs Cabangis G.R. No. L 28379 Mar. 27 1929Document4 pages07 Government Vs Cabangis G.R. No. L 28379 Mar. 27 1929Awe SomontinaNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform-Case DigestDocument12 pagesAgrarian Reform-Case DigestQuinnee VallejosNo ratings yet

- Jalover vs. YtoriagaDocument1 pageJalover vs. YtoriagaJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Rapid City 14Document4 pagesCiv Pro Rapid City 14Jill BetiaNo ratings yet

- PSTC Liable for LUSTEVECO Judgment DebtDocument2 pagesPSTC Liable for LUSTEVECO Judgment DebtDick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Integrating Schumpeter and KeynesDocument9 pagesIntegrating Schumpeter and KeynesDick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- 2DDocument3 pages2DDick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Assignment ADocument6 pagesAssignment Acary_puyatNo ratings yet

- Compilation R39, S15-S50Document24 pagesCompilation R39, S15-S50Dick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Effect of Family Income on Earnings of 16-22 Year OldsDocument1 pageEffect of Family Income on Earnings of 16-22 Year OldsDick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Tables 1 ADocument2 pagesTables 1 ADick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 CDocument2 pagesAssignment 1 CDick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Compilation R43 R45Document19 pagesCompilation R43 R45Dick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Rule 110-111Document281 pagesCriminal Procedure Rule 110-111Dick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- AFRS340Document5 pagesAFRS340Dick ButtkissNo ratings yet

- 516 FinalDocument7 pages516 Finalcary_puyatNo ratings yet

- Manchester vs. CA 149 Scra 562Document9 pagesManchester vs. CA 149 Scra 562albemartNo ratings yet

- PP vs. MondigoDocument3 pagesPP vs. MondigoElaine Aquino Maglaque0% (1)

- The Hon'Ble Supreme Court: BeforeDocument15 pagesThe Hon'Ble Supreme Court: BeforeMish KhalilNo ratings yet

- Digitel Director ResignsDocument26 pagesDigitel Director ResignsJacquilou Gier MacaseroNo ratings yet

- Bower v. Foster Farms Dairy Et Al - Document No. 5Document3 pagesBower v. Foster Farms Dairy Et Al - Document No. 5Justia.comNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Nervous ShockDocument8 pagesA Project Report On Nervous ShockSourabh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration - Atty. ElagoDocument10 pagesMotion For Reconsideration - Atty. ElagoTopelSama100% (1)

- Federal Court Awards Attorneys' Fees To Defendants Finding Slep-Tone Karaoke Lawsuit Was A ShakedownDocument2 pagesFederal Court Awards Attorneys' Fees To Defendants Finding Slep-Tone Karaoke Lawsuit Was A ShakedownCraig McLaughlinNo ratings yet

- Lyons Family LawsuitDocument39 pagesLyons Family LawsuitTodd Feurer100% (1)

- Adjudicative Support Functions of A COCDocument31 pagesAdjudicative Support Functions of A COCNadine Diamante100% (1)

- Facturan V Barcelona (PALE)Document2 pagesFacturan V Barcelona (PALE)Tiffany9222100% (1)

- (HC) Fentress v. Powers - Document No. 3Document1 page(HC) Fentress v. Powers - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Contempt If SC Orders Not FollowedDocument8 pagesContempt If SC Orders Not FollowedSridhara babu. N - ಶ್ರೀಧರ ಬಾಬು. ಎನ್No ratings yet

- Republic vs. Manotoc, G.R. No. 171701, February 8, 2012 - 665 SCRA 367 (2012)Document11 pagesRepublic vs. Manotoc, G.R. No. 171701, February 8, 2012 - 665 SCRA 367 (2012)Angeli Pauline JimenezNo ratings yet

- PP Versus Lovedioro, G.R. No. 112235 FactsDocument3 pagesPP Versus Lovedioro, G.R. No. 112235 FactsMarjun Milla Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Answer For Law of ContractDocument4 pagesAnswer For Law of ContractAzhari Ahmad50% (2)

- AbsconderDocument3 pagesAbsconderSanjeevNo ratings yet

- Victoriano Vs AlviorDocument5 pagesVictoriano Vs AlviorShazna SendicoNo ratings yet

- Hebron Vs LoyolaDocument3 pagesHebron Vs LoyolaJunelyn T. Ella100% (1)

- NLRC Abuse of Discretion ReviewedDocument3 pagesNLRC Abuse of Discretion ReviewedGigi Amparo MartinNo ratings yet

- Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Civil Aeronautics Board and Grand International Airways G.R. No. 119528, March 26, 1997 207 SCRA 538 FactsDocument9 pagesPhilippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Civil Aeronautics Board and Grand International Airways G.R. No. 119528, March 26, 1997 207 SCRA 538 FactsReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Five ICCPR Cases - SummaryDocument11 pagesFive ICCPR Cases - Summarywilfred poliquit alfecheNo ratings yet

- Anti-SLAPP Motion Filed Against Aster Graphics For Violating The Free Speech Rights of Steven GiannettaDocument77 pagesAnti-SLAPP Motion Filed Against Aster Graphics For Violating The Free Speech Rights of Steven GiannettaMark L. JavitchNo ratings yet

- United States v. Richardson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Richardson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Codal - Quasi Delict - 2176-2194Document2 pagesCodal - Quasi Delict - 2176-2194Mico Maagma Carpio50% (2)

- Ni Ritao Affadavit To BC's Supreme Court, S083484, 23092015Document3 pagesNi Ritao Affadavit To BC's Supreme Court, S083484, 23092015Ian YoungNo ratings yet

- Counter Affidavit GarzaDocument11 pagesCounter Affidavit GarzaDence Cris Rondon100% (2)

- People Vs BardajeDocument1 pagePeople Vs BardajeMarivic EscuetaNo ratings yet

- Ganaway Vs Quillen (Non-Imprisonment of Debt)Document2 pagesGanaway Vs Quillen (Non-Imprisonment of Debt)invictusincNo ratings yet

- Duncan V JonesDocument7 pagesDuncan V JonesTraversantNo ratings yet