Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brian Teare's Ecopoetics Talk

Uploaded by

michaelthomascrossCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brian Teare's Ecopoetics Talk

Uploaded by

michaelthomascrossCopyright:

Available Formats

We map our way with only the bearing of surrounding life itself borderless uncontrolled by the surface of our

self.

Ed Roberson, Eclogue

This excerpt from Robersons serial poem City Eclogue suggests our ultimate context is surrounding life, and that to navigate this surround is a complex task because it is both borderless and uncontrolled by us. A map that indicates only the bearing//of surrounding life would demand we dispense with the compass rose and cardinal directions; such a map would also demand we dispense with the expedient navigation weve become accustomed to. In asking us to imagine what such a map might be like and how it might shape our travels, I mean to ask if it is possible to create a linguistic eventa text or poemthat does not put human activity, alone, at the center of itself. I mean to ask what it means to take such care with our language, what it means for our language to care for the phenomenal world in which we are embedded: what does it mean for our language to care for the flora, fauna, rocks, and other biological and geological materials we treat as Others and upon which we wreak great violence? I mean to ask what it means for our language to care for surrounding life, but not to take care of it. And I mean to ask us to hear the duality of the phrase to take care of, which can mean both caretaking and killing, and either way implies the kind of hierarchy that underwrites both environmental stewardship and the century of accelerated ecocide weve entered. I mean, as Joan Retallack suggests in What is Experimental Poetry and Why Do We Need It?, that an ecopoethics of care entails finding new ways of being among one and others in the world via poetic forms (40). I mean that each of us is, as Brenda Hillman writes in Economics in Washington, a citizen of matter and beyond, but also that we live alongside non-human companions as citizens in the nation gathered in matter (53). And though the surrounding life of our non-human companions is a thing we cannot know in its totality, and though its ultimate structures constantly escape

scientists, philosophers, poets, and lawmakers alike, we dangerously proceed with science, thought, poetry, and policy as though our ignorance does not matter. I mean to ask, along with Retallack, How can the unalike know one another if know means to encounter and experience one another well? (42) I mean that, because of the anthropocentric presumptions of hierarchy latent in our cultural heritage, Homo sapiens, our language, and the surrounding life form a triad whose parts are in unusually fantastic tension. Though the roots of anthropocentrism are as old as Western culture itself, as detailed by Peter Coates in his study Nature: Western Attitudes Since Ancient Times, such anthropocentrism is the precondition for our turning the surrounding life into Nature, and the turn to Nature is in fact the precondition for the environmental crisis we find ourselves in. By Nature I mean a rhetorical figure from which we have exempted ourselves and that we have used, as Timothy Morton points out in The Ecological Thought, to create and sustain fictions of hierarchy, authority, harmony, purity, neutrality, and mystery (3). Our rhetoric of Nature has made possible endless figuration as well as endless violence and it is this relational paradox that concerns me, as conflict between the aesthetic and the political underwrites the intellectual tradition that has lead from environmental writing to ecopoetics. Consider this passage from Emersons essay Nature: Whoever considers the final cause of the world will discern a multitude of uses that enter as parts into the result. They all admit of being thrown into one of the following classes: Commodity; Beauty; Language; and Discipline. (25) It matters that Emerson lists Commodity as prime among the worlds purposes, and Beauty second, and that these lead both to Language and to Disciplinary thought. A sometimes fanatical evangelist of Natures servitude to Homo Sapiens, Emerson makes explicit how Commodity and Beauty are linked by their use value; he really believes that Nature, in its ministry to man, is not only the material, but also the process and the result. All the parts work incessantly into each others hands for the profit of man. The wind sows the seed; the sun evaporates the sea; the ice, on the other side of the planet, condenses rain on this; the rain feeds the plant; the plant feeds the animal; and

thus the endless circulations of the divine charity nourish man. (ibid) If during this era of chronic drought, wildfire, and melting ice caps it seems outrageously cynical to think the very wind sows seed for the profit of man, Id like to suggest that Emersons imagining of the endless circulations of divine charity also functions as metonymy for a larger tropological problem within the rhetoric of Nature that underwrites the intellectual heritage of environmentalism. I mean that work by feminist ecocritics as various as Carolyn Merchant, Val Plumwood and Rebecca Solnit suggest that Emerson, by positing Natures prime function as an endless reproductive circuit whose fruits (as capital or future citizen) fall rightfully into the hands of man, demonstrates the analogical link between the political fate of Nature as commodity and that of womens reproductive health within our sociocultural imaginary. I mean that anthropocentrism is also always already phallogocentrism, which suggests that a deep-seated misogyny is also one of the cultural preconditions for the emergence of the rhetorical trope of Nature, and that, as Plumwood writes in Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, One of the most common forms of denial of women and nature is what I will term backgrounding, their treatment as providing the background to a dominant, foreground sphere of recognised achievement or causation. This backgrounding of women and nature is deeply embedded in the rationality of the economic system and in the structures of contemporary societyWhat is involved in the backgrounding of nature is the denial of dependence on biospheric processes, and a view of humans as apart, outside of nature, which is treated as a limitless provider without needs of its own. (21) I mean that misogyny is also a precondition for our current environmental crisis, and though I will return to Plumwoods important notion of our denial of dependence on biospheric processes, I would first like to suggest that the strong analogical link between women and Nature, backgrounded though it may be, allows another equally insidious rhetorical trope to emerge: the designation of all forms of queer sexuality and gender as unnatural. If our cultural imaginary posits Nature as endlessly cyclical and reproductive and analogically links women to Nature through their shared capacity for reproduction and their ability to secure for Homo sapiens a future, we can see how and why our culture came to figure queers as non-reproductive and thus unnatural, perpetually existing in a rhetorical state that borders upon a form of abjection and a temporality that has no future.

Its this kind of figuration that has enabled politicians to claim AIDS to be either a form of divine punishment or an instance of Nature correcting its mistakes; its also the kind of figuration that has enabled environmentalists to cling to fatally tainted notions of purity, neutrality, and beauty. As Timothy Morton writes in his essay Queer Ecology, By repressing the abject, environmentalismsI am not denoting particular movements but suggesting affinities with, say, heterosexism or racismclaiming to subvert or reconcile the subject-object manifold only produce a new and improved brand of Nature. (274) Unlike Morton, however, I dont believe ecology is queer theory and queer theory is ecology (281), though of course I believe the disciplines can use each other as correctives, by which I mean I could now take this talk in any number of directions. Embedded in the trajectory Ive laid out are discourses on the heteronormativity of much environmental writing and activism as well as the implicit heterosexism of our collective emphasis on futurity; following these discourses, I could also propose a valediction of some form queer ecology, an embrace of categories of negativity, or a salvo concerning Lee Edelmans claim in No Future that Truth, like queerness, irreducibly linked to the aberrant or atypical, to what chafes against normalization, finds its value not in a good susceptible to generalization, but only in the stubborn particularity that voids every notion of good. The embrace of queer negativity, then, can have no justification if justification requires it to reinforce some positive social value; its value, instead, resides in its challenge to value as defined by the social, and thus in its radical challenge to the very value of the social itself. (6) Edelman has created controversy because hes challenged our collective faith in the potential good of human activity and sociopolitical systems, and in this hes a lot like the mid-century poet Robinson Jeffers, odd bedfellows though they may be. Edelman has issued his challenge to heteronormative and assimilationist gay social values via queer theory while Jeffers issued his challenge to anthropocentrism via poetry, both literary genres that have allowed their rhetorical violence to enter social discourse through highly specialized forms of language that largely shield society from the authors deep desire to do damage. In the case of Edelmans antisocial turn, we witness a strategy of critical reversal, a negation of our cultures fetishistic investment in the rhetorical figure of the

Child. With great sadistic relish, the following passage famously challenges the Childs metonymic representation of our collective future: Fuck the social order and the Child in whose name were collectively terrorized; fuck Annie; fuck the waif from Les Mis; fuck the poor, innocent kid on the Net; fuck Laws both with capital ls and with small; fuck the whole network of Symbolic relations and the future that serves as its prop. (29) In the case of Jeffers Inhumanism, we witness a strategy of uncritical reversal, which inverts our cultures a priori valuations of human and non-human life without too much problematizing of that stance: Id sooner, except the penalties, kill a man than a hawk, he famously writes in Hurt Hawks (165). Why? Because of civilization and the other evils it engenders, Jeffers writes elsewhere, misery and richesand squalid savagery/Mass war (399). Where Edelman rages against a collective heterosexist rhetoric that does damage to queer political life, Jeffers critique of anthropocentrism stems from existential and moral disappointment, and centers on the fact that human society has invented morality and the capacity for evil actions whereas as non-human life is structured by imperatives unbounded and uncontrolled by human morals and thus can do no evil. And though I deeply sympathize with both Edelman and Jeffers in their righteous antisocial anger, and believe that the figure of Nature functions a lot like the figure of the Child in policing the political lives of queers, I mean to hold close to feminist ambivalence about language and rhetoric and their power to do violence, especially when deployed by men in service of their own agendas of political critique. I mean I would rather suggest that the surrounding life remains the best radical challenge to the very value of the social itself because it cannot be essentialized and in its ontological strangeness remains unknowable in totality, indeed persisting as the strange stranger that Morton suggests it is, something that everywhere surrounds our language but cannot quite enter it. I mean I want to end with a valediction of the stubborn particularity we find only in the Real and only in attention to the strange strangers with whom we reside there, and though Edelman and Jeffers warn against making such particularities into allegories of positive social value, I want to suggest, in tandem with Elizabeth Grosz in Becoming Undone, that a valediction of the stubborn biological particularities we encounter in the present tense is a resistance of the normalization done in the name of Nature and persists as an embrace of the value of differentiation:

Difference is not the union of the two sexes, the overcoming of race and other difference through the creation or production of a universal term by which they can be equalized or neutralized, but the generation of ever-more variation, differentiation, and difference. Difference generates further difference because difference makes inherent the force of duration (becoming and unbecoming) in all things, in all acts of differentiation, and in all things differentiated. (47) Groszs hijacking of Darwinian evolutionary principles in the interest of a proliferation of social difference allows for temporality to be less about the heterosexual reproduction of Homo sapiens and more about duration in its largest sense, futurity less of a single horizon imbued with one universal value dependent on womens reproductivity, and more of a proliferation of various forms of life in various states of becoming and coming undone and with different relationships to futurity. I mean I am making my own figurative analogy between Edelmans stubborn particularity and Groszs durational differentiation because both of them attempt to resist the rhetoric of a anthropocentric universality that is often implicitly misogynist, heterosexist, and homophobic, and I am in turn linking them to acts of attention that immerse us in the deeply interdependent weave of being that feminist phenomenologist Gail Weiss in Body Images calls intercorporeality: The ground for this ethics is not a categorical imperative, nor is it the transcendence of consciousness as an annihilating activity that refuses too close an identification with any given action, relationship, or situation; rather it is an embodied ethics grounded in the dynamic bodily imperatives that emerge out of our own intercorporeal exchanges and which in turn transform our own body images, investing them and reinvesting them with moral significance. (158) I mean to suggest that the antisocial turn of recent queer theory could in fact be a turn toward something besides ourselves, toward bodies that indeed challenge the normalized boundaries of the social; rather than the difference normally constituted by human bodies designated Other by society and nation, however, the difference toward which we turn might in fact be the bodies of the flora, fauna and rocks, the strange strangers that surround us wherever we turn. And by we, I dont mean to reify dualist systems by implying that queers and women should carry the burden of representing the body with which they are always already associated, but to ask everyone interested in ecology and environmental justice to pay attention to and value experiences of human/non-human intercorporeality.

I mean that such an ecopoethical turn might end the denial of dependence on biospheric processes that Plumwood diagnoses as an essential element in the backgrounding of both women and nature in our sociopolitical realms, and that such a turn might create the embodied ethical transformations and moral significance that Weiss suggests stems from intercorporeal exchanges; such a turn might also enable queers who have felt alienated from the surrounding life by virtue of their abjection from Nature an opportunity to encounter and recognize their own dependence upon biospheric processes and to begin to extend community and care outward. I dont mean to suggest an encounter that becomes an allegory through which Homo sapiens reifies its identity in relation to a non-human Other that acts as mere mirror in which Man gazes upon Himself; I dont mean to suggest an encounter that recapitulates the imperialism of naming or scientific categorization, though meaningful forms of attention might include these gestures; I also dont mean to suggest such an encounter alone might constitute an effective form of environmental salvation. I do mean the immense pressure we put upon our rhetoric and activism is both noble and insane because Im not sure what local good can be done against widespread environmental destruction sanctioned by our most basic symbolic systems; along with Jack Collom, Im also suspicious of our anthropocentric emphasis on saving or taking care of the environment through the imposition of more rhetoric, more law, more metaphor from which totality again escapes, our vision of the surrounding life always too small, our knowledge incomplete. Save the act of saving, Collom writes in Things-to-save: the practice of saving, the habit of saving, the repetition but also save the resistance to saving in the sense that something saved is imprisoned in a vault, under lock and key I mean we shouldnt give up rhetoric or activism or care, but we probably have to save saving from itself, from becoming just another extension of our anthropocentrism. The bad thing about ecopoetry is that it is language, and therefore susceptible to figuration and to philosophical abstraction and to recuperating other forms of hierarchical ordering that can create and enforce social norms. The good that comes of ecopoetry is that its language is resistant to saving meaning under lock and key; it is language often aware of its own materiality and its participation in intellectual and cultural traditions that have been destructive of social freedoms, ecosystems, and species alike.

The good of ecopoetry lies in how its content often privileges a proliferation of lived difference, intercorporeal consciousness, and criticality; at the same time its ecopoethical forms demand of readers the immersion in the present tense that intercorpoerality and care both require; together its content and forms ask us to remain attentive to linguistic meanings residence in duration and in relation to the surrounding life without which we would have no bearings at all.

Works Cited Coates, Peter. Nature: Western Attitudes Since Ancient Times. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005. Print. Collom, Jack. Second Nature. Berkeley, Boulder, and Brooklyn: Instance Press, 2012. Print. Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. Print. Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Selections from Ralph Waldo Emerson. Ed. Stephen E. Whicher. Boston: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1957. Print. Grosz, Elizabeth. Becoming Undone: Darwinian Reflections on Life, Politics and Art. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. Print. Hillman, Brenda. Economics in Washington. Practical Water. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2009. Print. Jeffers, Robinson. Hurt Hawks and Still the Mind Smiles. The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Ed. Tim Hunt. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. Print. Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010. Print. _____________. Ecology without Nature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007. Print. _____________. Queer Ecology. PMLA, 125.2 (2010): 273-282. Print. Retallack, Joan. What is Experimental Poetry & Why Do We Need It? Jacket 32 (April 2007): n. pag. Web. 16 Feb. 2013.

Roberson, Ed. Eclogue. City Eclogue. Berkeley: Atelos, 2006. Print. Weiss, Gail. Body Images: Embodiment as Intercorporeality. New York: Routledge, 1999. Print.

You might also like

- Columbus's Outpost PDFDocument305 pagesColumbus's Outpost PDFGeffrey Marshall0% (1)

- Seigai 201123bDocument92 pagesSeigai 201123bNose Queponer50% (2)

- Merchant of Venice Script-1Document4 pagesMerchant of Venice Script-1AAYUSHI JAIN100% (1)

- Prosperity Affirmations From ScripturepdfDocument19 pagesProsperity Affirmations From Scripturepdfapi-26309515100% (2)

- Paper 2 Final DraftDocument8 pagesPaper 2 Final Draftapi-458722496No ratings yet

- Imre Szeman Zones of Instability LiteratureDocument259 pagesImre Szeman Zones of Instability Literaturemrsphinx90100% (1)

- Classic of TeaDocument68 pagesClassic of TeaShaiful BahariNo ratings yet

- Arab American Poetry As Minor - Fady JoudahDocument3 pagesArab American Poetry As Minor - Fady JoudahErica Mena-LandryNo ratings yet

- Grand Larcenies: Translations and Imitations of Ten Dutch PoetsFrom EverandGrand Larcenies: Translations and Imitations of Ten Dutch PoetsNo ratings yet

- Unsociable Poetry Antagonism and Abstraction in Contemporary Feminized PoeticsDocument255 pagesUnsociable Poetry Antagonism and Abstraction in Contemporary Feminized PoeticsZ2158No ratings yet

- Sex and Negativity Or, What Queer Theory Has For YouDocument26 pagesSex and Negativity Or, What Queer Theory Has For YouSilvino González MoralesNo ratings yet

- Wittig Mark of GenderDocument8 pagesWittig Mark of GenderRidge Darell DantesNo ratings yet

- AU Cairo Journal Article on Edward Said's Late StyleDocument10 pagesAU Cairo Journal Article on Edward Said's Late Stylestathis58No ratings yet

- Extremities-Rae ArmantroutDocument34 pagesExtremities-Rae ArmantroutArkava Das100% (1)

- Navratilova As 2010Document158 pagesNavratilova As 2010Mohamed NassarNo ratings yet

- 21 Love PoemsDocument2 pages21 Love PoemsNidal ShahNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press New Literary HistoryDocument20 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press New Literary HistoryFederica BuetiNo ratings yet

- Poetry Book Society Spring 2019 BulletinFrom EverandPoetry Book Society Spring 2019 BulletinAlice Kate MullenNo ratings yet

- CHRISTIANSEN, Steen - Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis RevisitedDocument191 pagesCHRISTIANSEN, Steen - Henri Lefebvre's Rhythmanalysis RevisitedtibacanettiNo ratings yet

- Butler, Judith - S Impact On Feminist and Queer Studies Since Gender TroubleDocument5 pagesButler, Judith - S Impact On Feminist and Queer Studies Since Gender TroubleDevanir Da Silva ConchaNo ratings yet

- Cha - Dictee (Excerpt)Document11 pagesCha - Dictee (Excerpt)Sunny100% (1)

- 5 Pillars of IslamDocument52 pages5 Pillars of IslamAzhari Bin MustaphaNo ratings yet

- Lyn Hejinian - RedoDocument15 pagesLyn Hejinian - RedoPkhenrique838541100% (1)

- Biochemic Salts and The Sun SignsDocument4 pagesBiochemic Salts and The Sun SignsRamanasarmaNo ratings yet

- LET Review Material 2019Document521 pagesLET Review Material 2019Judith Pintiano AlindayoNo ratings yet

- Dadabhoy BSA HaiderDocument12 pagesDadabhoy BSA HaiderAmbereen DadabhoyNo ratings yet

- 5 Steps To Avoid TemptationDocument1 page5 Steps To Avoid TemptationKENNETH IFEOSAMENo ratings yet

- Avant Canada: Poets, Prophets, RevolutionariesFrom EverandAvant Canada: Poets, Prophets, RevolutionariesNo ratings yet

- Politics of Literature J. RanciereDocument16 pagesPolitics of Literature J. RancierealconberNo ratings yet

- Unsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationFrom EverandUnsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationNo ratings yet

- James Boyd White - Reading Law & Reading Literature 1982Document32 pagesJames Boyd White - Reading Law & Reading Literature 1982krishaNo ratings yet

- Knowing Poetry: Verse in Medieval France from the "Rose" to the "Rhétoriqueurs"From EverandKnowing Poetry: Verse in Medieval France from the "Rose" to the "Rhétoriqueurs"No ratings yet

- 'Realms of Love': Gender and Language Fluidity in Tennyson's in MemoriamDocument34 pages'Realms of Love': Gender and Language Fluidity in Tennyson's in MemoriamAlyssa HermanNo ratings yet

- Taking Steps Beyond Elegy: Poetry, Philosophy, Lineation and DeathDocument13 pagesTaking Steps Beyond Elegy: Poetry, Philosophy, Lineation and DeathWilliam WatkinNo ratings yet

- Imperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandImperial Babel: Translation, Exoticism, and the Long Nineteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Poetry, Geography, Gender: Women Rewriting Contemporary WalesFrom EverandPoetry, Geography, Gender: Women Rewriting Contemporary WalesNo ratings yet

- How to Overcome the Tradition of Silence in Chicano SpanishDocument34 pagesHow to Overcome the Tradition of Silence in Chicano SpanishanamkNo ratings yet

- Legends of The Warring Clans, Or, The Poetry Scene in The NinetiesDocument226 pagesLegends of The Warring Clans, Or, The Poetry Scene in The Ninetiesandrew_130040621100% (1)

- TO THE READER: Bob Perelman's Unruly WorksDocument18 pagesTO THE READER: Bob Perelman's Unruly WorksButes TrysteroNo ratings yet

- Rethinking The Politics of Writing Differently Through Écriture FéminineDocument13 pagesRethinking The Politics of Writing Differently Through Écriture FéminineatelierimkellerNo ratings yet

- Hout - Cultural Hybridity, Trauma, and Memory in Diasporic Anglophone Lebanese FictionDocument14 pagesHout - Cultural Hybridity, Trauma, and Memory in Diasporic Anglophone Lebanese FictionmleconteNo ratings yet

- What Was Close Reading A Century of Meth PDFDocument20 pagesWhat Was Close Reading A Century of Meth PDFAntonio Marcos PereiraNo ratings yet

- Dislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationDocument8 pagesDislocating The Sign: Toward A Translocal Feminist Politics of TranslationArlene RicoldiNo ratings yet

- Translation, Poststructuralism and PowerDocument3 pagesTranslation, Poststructuralism and PowerRomina Ghorbanlou100% (1)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft and American Indian Poetry in the Romantic EraFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft and American Indian Poetry in the Romantic EraNo ratings yet

- Dadabhoy Public Humanities SubmissionDocument7 pagesDadabhoy Public Humanities SubmissionAmbereen DadabhoyNo ratings yet

- The Commons: Infrastructures For Troubling Times : Lauren BerlantDocument27 pagesThe Commons: Infrastructures For Troubling Times : Lauren BerlantAntti WahlNo ratings yet

- Moretti - Slaughterhouse of LitDocument22 pagesMoretti - Slaughterhouse of Litlapaglia36100% (1)

- Brathwaite, Kamau - ElegguasDocument137 pagesBrathwaite, Kamau - Elegguasmello754100% (2)

- Li Younglee PDFDocument18 pagesLi Younglee PDFJonathan SweetNo ratings yet

- An Interview With Michelle CliffDocument27 pagesAn Interview With Michelle CliffnilopezrNo ratings yet

- What Do We Do When We Teach Literature by Robert EaglestoneDocument9 pagesWhat Do We Do When We Teach Literature by Robert EaglestoneAngelica PamilNo ratings yet

- Beckett's Worldly Inheritors PDFDocument11 pagesBeckett's Worldly Inheritors PDFxiaoyangcarolNo ratings yet

- Negro Soy Yo, by Marc D. PerryDocument38 pagesNegro Soy Yo, by Marc D. PerryDuke University Press100% (1)

- Notes On Barthes SZDocument8 pagesNotes On Barthes SZRykalskiNo ratings yet

- Crossing Borders, Drawing Boundaries: The Rhetoric of Lines across AmericaFrom EverandCrossing Borders, Drawing Boundaries: The Rhetoric of Lines across AmericaNo ratings yet

- Songs of Innocence and Songs of ExperienceFrom EverandSongs of Innocence and Songs of ExperienceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- DefamiliarizationDocument25 pagesDefamiliarizationCheryl LatoneroNo ratings yet

- Disablity in Prose FictionDocument16 pagesDisablity in Prose Fictionall4bodee100% (1)

- Field Writing As Experimental PracticeDocument4 pagesField Writing As Experimental PracticeRachel O'ReillyNo ratings yet

- Where My Heart Is Turning Ever: Civil War Stories and Constitutional Reform, 1861-1876From EverandWhere My Heart Is Turning Ever: Civil War Stories and Constitutional Reform, 1861-1876No ratings yet

- Underglazy: Oki SogumiDocument30 pagesUnderglazy: Oki SogumiOkiSogumiNo ratings yet

- Elderly 3Document32 pagesElderly 3michaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Paranoid Histories ReaderDocument42 pagesParanoid Histories ReadermichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- New Poems by Brett PriceDocument21 pagesNew Poems by Brett PricemichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Elderly 2Document28 pagesElderly 2michaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Ted Rees's SonnetsDocument5 pagesTed Rees's SonnetsmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Geoffrey Olson's New ProseDocument5 pagesGeoffrey Olson's New ProsemichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Front Ear PartsDocument3 pagesFront Ear PartsmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Nielson Owens DialogDocument9 pagesNielson Owens DialogmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Brian Teare's Ecopoetics TalkDocument9 pagesBrian Teare's Ecopoetics TalkmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Supple Science: A Robert Kocik ReaderDocument3 pagesSupple Science: A Robert Kocik ReadermichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- The Idiot Stone: George Oppen's Geological Imagination by Rob Halpern (Draft)Document16 pagesThe Idiot Stone: George Oppen's Geological Imagination by Rob Halpern (Draft)michaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Jalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Resurrected GodDocument7 pagesJalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Resurrected GodmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Brian Teare's Ecopoetics TalkDocument9 pagesBrian Teare's Ecopoetics TalkmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Skinner's Advisory Board Roundtable CommentsDocument6 pagesJonathan Skinner's Advisory Board Roundtable CommentsmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- The Idiot Stone: George Oppen's Geological Imagination by Rob Halpern (Draft)Document16 pagesThe Idiot Stone: George Oppen's Geological Imagination by Rob Halpern (Draft)michaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Woman-As-City Woman-In-City: Babylon, Oakland & Me by Yosefa RazDocument4 pagesWoman-As-City Woman-In-City: Babylon, Oakland & Me by Yosefa RazmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- A Poetics That Lives in The City: An Opening Conversation On Prosody, Political Economy, and City EcologyDocument6 pagesA Poetics That Lives in The City: An Opening Conversation On Prosody, Political Economy, and City EcologymichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Jalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Lived Then Died!Document6 pagesJalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Lived Then Died!michaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Notes Toward An Ecology of Time by Laura MoriartyDocument4 pagesNotes Toward An Ecology of Time by Laura MoriartymichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Geologic Time (Bomb) : Helen Adam's Superstitious Activism by C.J. MartinDocument13 pagesGeologic Time (Bomb) : Helen Adam's Superstitious Activism by C.J. MartinmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Crisis Inquiry EditorialDocument6 pagesCrisis Inquiry EditorialmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Jalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Resurrected GodDocument7 pagesJalal Toufic, The Resurrected Brother of Mary and Martha, A Human Who Resurrected GodmichaelthomascrossNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Essay On Racial ProfilingDocument5 pagesPersuasive Essay On Racial ProfilingAbdul Haseeb100% (1)

- Prof BoundariesDocument36 pagesProf BoundarieshalayehiahNo ratings yet

- EuergetismDocument173 pagesEuergetismsemanoesisNo ratings yet

- Confirmation Outside Mass Revised 2016Document7 pagesConfirmation Outside Mass Revised 2016eugene alisNo ratings yet

- Jesus' homeland of PalestineDocument11 pagesJesus' homeland of PalestineMitsi Mae RamosNo ratings yet

- Barry Long 10 Book OfferDocument1 pageBarry Long 10 Book OfferRey NulsNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 From The Act To The PersonDocument3 pagesLesson 3 From The Act To The PersonDale JayloniNo ratings yet

- Mooney SBJT Fall 08 2Document18 pagesMooney SBJT Fall 08 2Al-FarakhshanitiNo ratings yet

- Thrice-Greatest Hermes, Vol. 3Document300 pagesThrice-Greatest Hermes, Vol. 3Gerald MazzarellaNo ratings yet

- MCQs For TestDocument14 pagesMCQs For TestHikmat Agha100% (1)

- Major Indian Sculpture SchoolsDocument10 pagesMajor Indian Sculpture SchoolsHema KoppikarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 of CFCDocument5 pagesChapter 13 of CFCTrisha Mae Mendoza MacalinoNo ratings yet

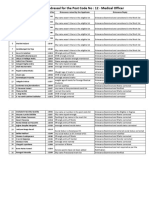

- Post Code-12 Medical OfficerDocument25 pagesPost Code-12 Medical OfficerDr.vidyaNo ratings yet

- AGuideToKything RebeccaCampbell+Document6 pagesAGuideToKything RebeccaCampbell+FabyLizárragaGalvánNo ratings yet

- Prayer (Long) (All Religions)Document6 pagesPrayer (Long) (All Religions)Anousha100% (2)

- Jesus (PBUH) Did Not Die According To QuranDocument6 pagesJesus (PBUH) Did Not Die According To QuranManzoor AnsariNo ratings yet

- The Judgement of ParisDocument1 pageThe Judgement of Parishundpercent123No ratings yet

- OutsidemeluhhaDocument266 pagesOutsidemeluhhaapi-20007493No ratings yet

- Family 3 Hours With God For Divine Restoration PDFDocument1 pageFamily 3 Hours With God For Divine Restoration PDFDele AdigunNo ratings yet

- Hanuman: Lord of Strength and WisdomDocument15 pagesHanuman: Lord of Strength and Wisdommukca4824No ratings yet