Professional Documents

Culture Documents

978 1 4438 0989 4 Sample PDF

Uploaded by

Klv SwamyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

978 1 4438 0989 4 Sample PDF

Uploaded by

Klv SwamyCopyright:

Available Formats

Occupational Mobility Among Scheduled Castes

Occupational Mobility Among Scheduled Castes

By

Jagan Karade

Occupational Mobility Among Scheduled Castes, by Jagan Karade This book first published 2009 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright 2009 by Jagan Karade All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0989-6, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0989-4

DEDICATED TO

Lord Gautam Buddha,

The Pioneer of Equality and Peace

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword .................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... xi List of Abbreviations ................................................................................ xiii Chapter One................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 28 Review of Literature Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 41 Methodology Chapter Four.............................................................................................. 49 The Scheduled Castes in Maharashtra and Kolhapur city Chapter Five .............................................................................................. 69 Inter-Generational Occupational Mobility Chapter Six .............................................................................................. 112 Intra-Generational Occupational Mobility Chapter Seven.......................................................................................... 141 Conclusion and Suggestions Appendix I............................................................................................... 148 Scheduled Castes in India (State wise) Appendix II.............................................................................................. 159 22 Vows of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Appendix III ............................................................................................ 161 Forms of Discrimination

viii

Table of Contents

Bibliography............................................................................................ 162 Author Index............................................................................................ 173 Subject Index ........................................................................................... 175

FOREWORD

Post-Independence Indian society is undergoing several and, some areas and rapid changes. The process of urbanization, industrialization, the spread of modern education, and that of means of communications and transport are major factors which account for these changes. The goal of establishing a welfare state in the country has also played an important role in strengthening the impact of the above factors on the society as a whole. Since these factors are secular and autonomous, these have affected all socio-economic and cultural groups in the Indian society to a greater or lesser extent depending upon, among other things, the capacity to benefit itself from the process of overall socio-economic development. In view of a stratified, an unequal, and in egalitarian Indian society, again among other things, due to many socio-economic and cultural factors but mainly due to the prevalence of the caste system, the Indian state introduced, in the Constitution itself, several special provisions for the SCs and STs, the most disadvantaged sections of the Indian society for centuries, for their faster progress and bridge the gap between them and the general population sooner than later. The special provisions are instrumented thorough the Reservation Policy, the Indian version of an anti-discriminatory affirmative action. The Constitution of free India, thus, made provision of reserving a certain number of seats, generally in the proposition of the population for the SCs and STs, in the spheres of education, public employment, and Central and State legislatures. Notwithstanding, defective and even faulty implementation of the Reservation Policy, it must be admitted that, it played a catalyst role in securing the overall development of the members of the SC and ST communities. Like all other societies, in the case of SCs and STs also, education played a very crucial role in enabling these communities to access the

Foreword

benefits of economic development. Elementary, secondary, higher, technical and professional education helped these communities to break the shackles of traditional occupations with abysmal earnings and source of all socio-cultural stigma and indignities. Particularly higher and professional education, made them occupationally mobile, both from rural to urban, and also horizontally and vertically. In the present study, Dr. Karade has made a systematic attempt to establish an already acknowledged positive co-relation between education and occupational mobility. What attracts ones attention, however, is the fact that Dr. Karade has studied both inter-generational (three generations of the same family) and intra-generational occupational mobility. Though his sample is relatively small comprising 186 respondents in the Kolhapur city of Maharashtra, his conclusions are neat and, therefore, would be acceptable. For instance, the members of the Buddhist community are well ahead in securing higher, professional and technical education compared to the other non-Buddhist SC communities. Dr. Ambedkars historical movement for the emancipation of the untouchables and his personal role model had more profound impact on the Buddhist community vis--vis the others. Second, even those who have secured higher education and obtained better positions in terms of economic and social status are also not able to overcome the prejudices at the hands of the upper castes and thus could not totally escape from the discrimination at the latters hands. Third, so far intra-generational occupational mobility is concerned; Dr. Karade rightly observes that the successive generations of the SC communities aspire for still better occupational positions as these impart social prestige along with material empowerment. Dr. Karade also has drawn attention to an erosion of the Reservation Policy due to declining space of the State in the economic activities in the aftermath of the process of globalization, liberalization and privatization. Like many other concern academicians from the disadvantaged sections of the society, Dr. Karade too has suggested to introduce affirmative action in the private sector. I am sure; Dr. Karades present work would be well received by the researchers and readers in general as well. Dr. Bhalchandra Mungekar Yojana Bhawan New Delhi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The various castes in the Hindu social organisation are divided into a hierarchy of ascent and descent (one above the other). To the sense of superiority is also co joined the law of untouchablility. The feeling of superiority is much exaggerated and manifest in all over India. The system of untouchablility has resulted in injustice to some low castes of Hindu society. Therefore, some castes had been socially, economically and culturally exploited for centuries which are listed as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. After independence, Constitution of India has made provision of protective discrimination policy, especially Reservation policy. Therefore many persons of Scheduled Castes left their traditional occupations and took responsibilities of new job or position, but those who have taken education and those who have developed skills are taking more benefit and the tremendous change is observed in connection with their family as well as society. This book focuses on the nature of occupation and factors which are more related to Inter-generational as well as Intra-generational occupational Mobility in the society. The present work is a slightly revised version of my Doctoral thesis submitted to University of Mumbai, Mumbai. Many scholars have helped me either directly or indirectly in one way or other in completion and publication of the book. This book is enriched by opinions and teachings of experts and co-operation and discussions with persons belonging to various age groups and holding various positions in the educational field. Grateful acknowledgements are due to Dr. Bhalchandra Mungekar, Member, Planning Commission, Government of India and former vicechancellor, University of Mumbai, Mumbai for writing the Foreword and encouraging me to get it published and I would like to express my gratitude to my research guide Dr. P.G. Jogdand, Professor, Dept. of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai for his incessant stream of inspiration and advice.

xii

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Dr. Uttamrao Bhoite, Dr. Sharmila Rege (Pune), Dr. Rajendra Patil, (Kolhapur), Dr. Richard Pais (Manglore), Dr. R.K. Kale (New Delhi), Dr. M.H. Makwana (Ahmadabad), Dr. Bhagwan Bhist (Nainital), Dr.Vimal Trivedi (Surat), Dr. Praveen Jadhav, Prof. Shankar Bhoir, Mr.Ravindra Abhyankar, Mr. Raju Dabade (Pune), Prof. Sanjay Khilare, Prof. Sunil Ogale (Baramati) and the Library staff of Tilak Maharashtra University, Pune, Surat Study Center, Surat, Pune University, Pune for their friendly cooperation and assistance from time to time. I am also very grateful to vice-chancellor Dr. Deepak Tilak and Registrar Dr. Umesh Keskar, Tilak Maharashtra University, Pune and my colleagues for their co-operation and motivation. I am thankful to Indian Council of Social Science Research, New Delhi (ICSSR) for giving Contingency Grant for the research work. I am also thankful to my father-in-law Adv. S. G. Sudarshani and motherin-law Mrs. Sudarshani, Adv. Nanasaheb Mane (Ex. M.L.A.), Mr. Gautamiputra Kamble, Principal Dr. Harish Bhalerao, Dr. N.S. Maner (Kolhapur) as well as my teachers who taught me in Dr. Ambedkar College of Arts and Commerce, Peth Vadgaon and Department of Sociology, Shivaji University, Kolhapur. I am thankful to all the authors of various books and reports referred to in this study, I am also thankful to all the interviewee, who helped me at every stage. Without their information I could not have completed this book. Words cannot express my feeling for my family members: my mother Indumati, wife Sujata, children Utkarsha, Ujjwal, nephew Atul and Rahul who encouraged me to reach up to this stage. It is difficult to name all, but I offer my sincere thanks to all those who have directly and indirectly helped me in completing this book. Lastly, I would like to thank Cambridge Scholars Publishing, United Kingdom and their associate especially Ms. Amanda Millar and Ms. Carol Koulikourdi for bringing out the book in short time. Jagan Karade, Pune, 9th May, 2009.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

B.Ed. B.S.P D.T. Dy. EPW M.B.B.S M.D. N.T. OBC RPI S.B.C. S.S.C. SC SCs ST STs

Bachelor of Education Bahujan Samaj Party De-notified Tribe Deputy Economic and Political Weekly Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery Doctor of Medicine Nomadic Tribes Other Backward Class Republican Party of India Special Backward Class Secondary School Certificate Scheduled Caste Scheduled Castes Scheduled Tribe Scheduled Tribes

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION

CONTENTS Conceptual framework Mobility Occupation Inter-generational occupational mobility Intra-generational occupational mobility Transition of the Scheduled Castes Vedic period 1400-600 B.C. Post-Vedic period Manusmriti period 200 B.C. A.D. 200 Muslim period British period Post Independence period Caste and Occupation Caste and Occupational prohibition Awareness about caste discrimination among SCs in the British period The efforts of social reformers The role of Dr. Ambedkar Post Ambedkar scene Summary

Chapter One

The social development of the world has been geared up in the last century. The social, economic and political movements and upheavals not only affected the traditional values but they challenged the moral values of the world. This milieu affected the developing nation like India too. A large section of Indian population called as untouchables was deprived of their basic, legitimate human rights to live with dignity. They suffered from many inhuman disabilities. Moreover, the factor that was most striking was the institution of untouchability. The ex-untouchables (now designated as Scheduled Castes) occupied the lowest rank in the social hierarchy of Hindu caste system. They were the most oppressed and downtrodden of the Indian society. They were always exploited socially, economically, educationally and culturally too, by the upper castes. After independence, the Constitution of India made certain provisions for the upliftment of SCs and STs. The Government has laid down three kinds of arrangements for them. First, there is reservation of seats in the Parliament and State legislatures, secondly; reservation of jobs in the Government and Semi Government services, lastly, seats have been reserved in the educational institutions especially in institutions of the higher learning such as Colleges and Universities for their social and educational advancement.1 As a result, people sought employment away from their native exploitative system. Now persons of SCs are in a position to enter into non-traditional occupations in urban area.

Conceptual framework

The present book is an empirical study probing the occupational mobility amongst SC employees who have been working in a University and Government aided and non- aided Arts, Commerce and Science, B.Ed. and special B.A.,B.Ed. Colleges in an urban setting. Many Sociologists and Anthropologists have brought out this aspect of the correlation between caste and occupation. On the one hand with regard to certain caste groups and at the same time the flexibility and facility for occupational mobility, which was structured with the caste system. This study discusses the intergenerational and intra-generational occupational mobility among three generations of SCs. In addition to this, the study is focused on the

Xaxa Virginius, 2001, Protective discrimination: Why Scheduled Tribes lag Behind Scheduled Castes, EPW, Vol. No. 35 (29), July 21, Pp. 2765.

Introduction

motivating factors, which have resulted into occupational mobility among SC communities.

Mobility

Different authors have defined mobility in different ways. Pitrim Sorokin first formulated the concept. He defined social mobility as any transition of an individual or social object or value, anything that has been created or modified by human activity, from one social position to another. 2 Barber says the term social mobility has been in use for movement, either upward or downward between higher or lower social classes, or more precisely, movement between one relatively full time functionally significant social role and another, that is evaluated as either higher or lower.3 According to Lipset and Bendix, the process by which individuals move from one position to another in society positions, which by general consent have been given specific hierarchical values. 4

Occupation

Occupation is one of the best indicators of class, because people tend to agree on the relative prestige they attach to similar jobs. Those at or near the top rung of the prestige ladder usually have the highest income, the best education, and the most of the power. The sociologists view work as an action performed with the object of achieving some particular objective. This gives two meanings. In the first place the player gets some satisfaction of his physical and psychological need. In the second place, it is not possible to draw a dividing line between play and work. The same activity may be a game for one individual and work for another. Many sociologists opined that; the occupation of a person reflects his socio-cultural status. The sociologist conceived that, as the movement from one occupational category to another, the persons category consists

2 3

Sorokin, P. A., 1927, Social and Cultural Mobility, Harper and Brothers, P.43. Barber Bernard, 1957, Social Stratification, A comparative Analysis of Structure and Process, Harcourt, Brace & Co., New York, Pp. 17. 4 Lipset S.M. and Bendix R, 1959, Social Mobility in Industrial Society, University of California Press, California, Pp. 103.

Chapter One

of manual to non-manual, semi-skilled to skilled and some rank, which consists with the social and cultural prestige. The occupational mobility in the present context refers to the transition from one occupation to that of another. This may occur in two different directions, horizontally and vertically. Inter-generational occupational mobility: - In the inter-generational occupational mobility, it should be examined whether father influences occupational position of the respondent (son / daughter). The occupation indicates that, whether a particular group or section of population is engaged in primary, secondary or tertiary occupation, which is positive index of development. In the inter-generational occupational mobility, the respondents have changed their occupation compared to the occupation of their fathers. [For details, see Miller S.M., (1960) ] Intra-generational occupational mobility: - In the intragenerational occupational mobility, one position or one point of an individuals career is compared with another position or point of his /her career.5

Transition of the Scheduled Castes

Vedic period 1400-600 B.C.

The foundation of untouchability was laid in Ancient times. The immigrant Aryans were very different from the non-Aryan dark people whom they found living in India. Aryans considered themselves superior and were proud of their race, language and religion. They considered nonAryans to be non-humans or amanushya6 And the non-Aryans were described as Krishna Varna or dark-skinned, anasa or without nose (snubnosed), those who speak softly and worship the phallus.7 The Aryan, whiteskinned, making sacrifices and worshipping gods like Agni, Indra, Varun etc. were distinguishable ethnically and culturally from the Dasas or Dasyus, who were black-skinned and large number of Dasas were taken

Miller S.M., 1960, Comparative social mobility, Current Sociology, Vol. IX No.1, Pp. 5. 6 Rigveda, 1981: X. 22.9, Quoted by Shrirama, Untouchability and Stratification in Indian Civilisation, in Michael S.M. Edit, Dalits in Modern India, Vistaar Publication, New Delhi, Pp.37. 7 Ibid

Introduction

as slaves instead of being exterminated.8 In the later Vedic period (1400600 B.C.) it resulted in the gradual withdrawal of the ruling race from all professions requiring manual labour and the generation of a spirit of contempt for industrial arts, which fell more and more into the hands of the Shudras. The greater association of slave or Shudra labour with certain branches of industry, together with the growing contempt for manual labour made the industries low in the estimation of the higher classes, and made low those engaged therein. 9 The idea of ceremonial impurity of the Shudra involving prohibition of physical and visual contact with him appeared towards the close of the Vedic period (1000-600 B. C.)10. The Shudra was permitted to take part in certain rituals and yet excluded from several specific rituals as well as from the Vedic sacrifice in general.11

Post Vedic period

The difference between the Vaishayas and the Shudras was getting narrower day by day into the pre-Mauryan period (600- 300 B.C.) During the Ramayana and Mahabharata the condition of the Shudra had deteriorated.12 The social position of the Shudra underwent a change for the worse. With the complete substitution of society based on Varna during post-Vedic times, the members of the Shudra Varna ceased to have any place in the work of administration. The law givers emphasized the old fiction that, the Shudra was born from the feet of the God, and apparently on this basis imposed on Shudra were numerous social disabilities in matters of company, food, marriage and education. In several cases this led to his social boycott by the members of the higher Varnas in general and the Brahmins in particular13. This period also saw the emergence of Buddhism and Jainism as alternatives to the prevalent

Chatterjee S. K., 1996, The Scheduled Castes in India, Vol. No. 1, Gyan Publishing House, New Delhi, Pp. 52. 9 Dutt, N. K., 1968, Origin and Growth of caste in India, Vol 1, Firma K. L. Mukhopadhayaya, Cultutta, Pp. 3. 10 Chatterjee S.K., 1996, Op.Cit, Vol. No.1, Pp. 53. 11 Keith A.B, Cambridge History of India Pp. 120. 12 Massey James, 1998, Dalits: Issues and concerns: India, 50 years of Independence: 1947-97, status, Growth and development, Vol-20, B.R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi, Pp. 47. 13 Sharma R. S, 1958, Shudra in Ancient India, Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi, Pp. 2829.

8

Chapter One

religious beliefs and practices. Gautam Buddha is very often complimented for refusing the caste system. According to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar14, the Shudras belonged to the Kshatriya class in the Mahabharat period and later on they were brought to Shudra class. According to Pillai,15 Untouchability has its origin in hygiene first and then in religion. Ghurye16 concludes that, the idea of untouchability has been traced to the theoretical impurity of certain occupations. The early Pali texts often mention the five despised castes as the Chandala, Nishada, Vena, Rathakara and Pukkasa. They are described as having low families (nicha Kula) or inferior births (hina Jati), but Dharmsutras did not treat all of them as untouchables. Only Chandalas and Nishadas were considered as untouchables in later Vedic society collectively. The untouchables were known as the Antyas or Bahyas i.e., people living outside villages and towns. Generally, the untouchables lived at the end of villages or towns or in there own settlements.17 During the Rigvedic period itself two non-priestly (non-Brahmin) princes belonging to Kshatriya (Warriors) caste, Mahavira (540 B.C. 468 B.C.) the founder of Jainism and Gautam Buddha ( 563 B.C. - 483 B.C.) the founder of Buddhism also revolted against the supremacy of the Brahmins.

Manusmriti period 200 B.C. A.D. 200

The Manusmriti, desperately tried to revive the bygone golden age by reestablishing the ancient system of Varna hierarchy. In this process women and Shudras were the greatest losers. It tried to assign each and every ethnic group, whether Indian or foreign a specific place in the Varna

14 Ambedkar B.R.,1947, reprinted, Who were the Shudras ?, Thacker & Co. Ltd., Bombay, Pp. 121-126. 15 Pillai G. K., 1959, Origin and Development of Caste, Kitab Mahal, Allahabad, Pp. 176-184. 16 Ghurye G. S., 1990 fifth Edition, Caste and Race in India, Popular Prakashan, Bombay, Pp. 159. 17 Sharma R.S., 1958, Op. Cit. Pp. 130-132.

Introduction

system according to its own criteria.18 The Manusmriti accepts only the twice birth three castes: Brahman, Kshatriya and Vaishya, but the fourth. Shudra has only one birth. It says, There is no fifth Caste 19 to explain the existence of those who were not of the four castes. Manusmriti put forward the concept of mixed castes, which included those who were born out of inter-caste marriages.20 They are called as Chandala and Sapaka. Therefore, Brahmin groups hated Chandala and Sapaka. Many of them tried to assign work each and every ethnic group and followed the guidelines laid down by the Dharma sutras. The Smritis attributed to Yajnavalkya, Brihaspati, Narada and Katyayana followed the institutes of Manu. The Varna hierarchy influenced a lot the legal system, since Brahmans were placed highest in the social structure; they enjoyed the highest privileges. The life of a Brahman is given the highest esteem while the Shudras, the lowest. Manu ordained that the mixed castes should live near well-known trees and burial grounds, on mountains and in groves but the Chandalas and the Sapakas should live outside the village. The vessels used by them were discarded forever. Their sole property consisted of iron and clothes of dead people and wandered from place to place.21 Manu wanted to avoid all contacts between the Brahmins and untouchables. Manu declared that if Brahman had intercourse with Chandala or Antya women or took their food, he would lose his Brahmanhood. But if he did these things intentionally, his status will be reduced.22 In this way the period of the Aryan colonization reaching its completeness around A.D. 700 and continues till date. This long period was dominant, almost 1000 years. (A.D. 700-1700)

Shrirama, Untouchablilty and stratification in Indian civilization, In Dalits in Modern India: Vision and values, edited by Michael, Vistaar Publications, New Delhi, Pp. 63. 19 Burnell Arthux Coke (Tr.): The ordinance of Manu, New Delhi 1971, XXIII (Introduction Page) (also see Fr, Zacharias, 1956, An outline of Hinduism, Alwaye, Pp. 323. 20 Narain Suresh, 1980, Harijans in Indian society, Aminabad, Pp. 25-28 21 Manu x. 50-52 quoted by 1.Ketkar S.V., 1979, History of Caste in India. Rawat Publications, Jaipur, Pp. 104. 2. Burnill Arthue Coke, (Tr.) 1971, The ordinance of Manu, New Delhi, Pp. 312. 22 Sharma R.S., 1958, Op. Cit., Pp.204-8.

18

Chapter One

Muslim period

After the death of Harsha (A.D. 647) who was the king of Thaneshwar, the dark days of Indian history began. Since A.D. 712 the Muslims came to India as travelers, traders and mercenaries. Their armies had over-run the entire country from Punjab to Assam and Kashmir to the Vindhyas23. The Muslims settled firmly in India from the 11th century onwards. It is noteworthy that the position of the Shudra improved a great deal between 11th and 12th centuries. As the Vaishyas came under the doctrine of ahimsa giving up agricultural activities, the Shudras were nearer to Vaishyas. They toiled the soil and also acted as caravanleaders.24 As a result, the Shudras gradually improved their economic condition. Their lot further improved with the reformist movements like Jainism and Saivism, which welcomed them in their fold, in no way treating them as inferior to the Brahmans. But intellectually they remained rather backward, because higher education was largely restricted to the elite- the Brahmanas and Kshatriyas.25 Later on the Portuguese occupied some parts of India in the early 16th century, which effected fresh conversions of Hindus into Roman Catholics. When Hindu kings conquered the countries occupied by Muslims or Portuguese rulers, those converts were reconverted into Hinduism. All these further increased the number of Castes.26 This period is very crucial for the Hindu religion because many people affected by Islam were there, at that time. The Bhakti movement led by Acharya Ramanuj (1017-1200) Madhavacharya (1238) Vallabhacharya (1479-1533) Kabir (1440-1518) Guru Nanak (1469-1539), Chaitanya (1486-1533) Tulsi Das (1532-1623) and many others did help check Islamisation of India. Under the Islamic influence many who had converted to Islam, like Harihar and Bukka, came back to the Hindu fold. 27 According to Lal28 Namdeva, Ramdas, Eknath, Ramanand, Kabir, Nanak and Chaitanya and several other saints had Muslim disciples. Many of whom converted themselves to the Hindu

For details see, Chatterjee S. K., 1996, Op. Cit., Vol. No. 1, and Pp. 68-69. Sham Brijendra Nath, 1972, Social and cultural History of Northern India 10001200 A.D., Abhinav Publications, New Delhi, Pp. 28. 25 Chatterjee S.K., 1996, Op.Cit, Vol. No. I, Pp. 70. 26 For details see, Adik Ramarao, 1961, Brahmonism without casteism, Bombay, Pp. 44-45. 27 Chatterjee S.K., 1996, Op.Cit, Vol. No. 1, Pp. 71-72. 28 Lal K. S., 1990, Indian Muslims: who are they, Voice of India, New Delhi, Pp. 111-113.

24 23

Introduction

Bhakti cult. Chaitanya openly converted Muslims to the Bhatkti cult of Hinduism. In the pre-Mauryan period, the difference between the Vaishyas and Shudras was getting narrower day by day. The occupations of the two varnas were practically interchangeable. The general rule was that in times of distress each Varna may follow the occupation of that next below it in rank, So the Vaishyas who were rigidly shut out from the occupations of the higher varnas, freely took to those of the Shudras. While the latter in distress were permitted to follow the professions of the Vaishya varna (Yajnawalkya smirit 1.120). Later on Shudras could be found in the professions of cattlebreeding and agriculture not only in exceptional circumstances but also at all times. (Kautilya Arthashastra, 1.3.) Thus in the medieval India the artisan classes, such as carpenters, weavers, potters, blacksmiths, etc., who had, in the Rigvedic society, belonged to the Vaishya varna were ranked as Shudras. The recognized professions of the Vaishya were four in number viz., agriculture, earning from cattle, trade and money lending (Yajanwalkya smriti, 1.119). Al-beruni an 11th century visitor to India describes, the Vaishyas, like the Shudras were not allowed to hear it (i.e. the Vedas) much less to pronounce and recite it.29 After that, the revival of the Maratha military power, in the 17th century however, arrested the process of disappearance of the Kshatriya Varna there. The stubborn resistance offered by the Chandraseniya-Kayastha Prabhu in the 18th century foiled the Brahmanical efforts, though backed by the support of some of the Peshwas like, to deprive them forcibly of the use of the sacred thread and to reduce them to the status of Shudras. 30

British period

The British period actually began with the inauguration of the East India Company (London) in A.D. 1599.31 But for the first 150 years the East India Company showed interest only in business and trade. Lord Robert Clive turned it into a military power from 1744 A.D. onwards 32and the British established their own traditional form of Government. But they could not have sympathy with the institution of the Hindus. At that time they introduced a system of education, which did not demand, from the learners any change of religion. Ideas and behavior patterns, very different from those to which the people were accustomed, were thus presented as

Sacahu E.C., 1914, Al-berunis India, Vol. II London, P. 36. Chatterjee S.K., 1996, Op.Cit, Vol. No. 1, Pp. 76. 31 Kaye John willam, 1959, Christianity in India, London P. 38. 32 Watson, Francis: A coucise History of India, Southampton, 1981, (Reprint) Pp. 125.

30 29

10

Chapter One

isolated from religion.33 Meanwhile the Christian missionaries work which concerned with the various Indian traditions to evaluate and rethink their approach to the weaker section because Hindu society did not give any civil rights to untouchable people. Ghurye 34 has noted that, there was such distinct discrimination during British period. The western education also brought about a change in the outlook of the educated youth who under the leadership of social reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy (17721833) Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820-1891) Swami Dayandanda Saraswati (1824-1833) Justice Ranade (1842-1901) Mahatma Jotiba Phule (1827-1890) Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) Dr. Ambedkar (1891-1956) and others introduced many social reforms including abolition of untouchability and they strove for the development of lower castes. Beside this, the British activities, such as the growth of towns, industries and introduction of railways, they established the hotels and eating-houses etc. contributed to the relaxation of caste prejudices. These factors attacked the caste system. During this period new phrases were coined to denote the Dalits. For example, for the first time the existence of the Depressed Classes was recognized in the text of the Act of 1919.35 According to Dr. Ambedkar, in the report of 1910 was the first time the Hindu people were divided in three classes, viz. 1. Hindus 2. Tribes 3. Dalits.36 In 1931 the census superintendent of Assam made a suggestion to change the title from the Depressed Classes to the Exterior Castes. The argument for this suggestion was that, it is a broader title, because its connotation does not limit itself to outcaste people (which means people who are outside the caste system) but on the other hand, Exterior Castes would include those who had been cast out because of some breach of rules.37 The Government of India (British Indian Provinces) Act 1935 used the term Scheduled Caste for the first time. Then the Government of India published a list of Scheduled Castes in 1936.38 In this order, 417 castes

Ghurye G. S., 1969, 5th edit., Caste and race in India, Popular Prakashan, Bombay, Pp. 270. 34 Ghurye G. S. Ibid. P.p. 275. 35 Lokhande G. S., 1982, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, New Delhi, P. 181. 36 Dr. Ambedkars Writings and Speeches ,Vol. No. 7, Book 2, Education department, Government of Maharashtra, 1990, Pp. 311. 37 Hutton J. H., 1946, Caste in India, Oxford University Press, Delhi, Pp. 167. 38 Kamble N. D., 1982, The Scheduled Castes, Ashish Publishing House, New Delhi, Pp. 31.

33

Introduction

11

were listed but actually, there were 450 castes, considering each of the castes / sub castes etc., which are grouped together as a separate entity. Afterwards Mahatma Gandhi took up the work of redeeming the untouchables but the matter did not receive any momentum. Gandhiji called them Harijans (Children of God) and organized a network of agencies, which worked for their causes.

Dr. Ambedkars perspective on Caste system

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar deals with the subject of castes system from the anthropological point of view. According to him the population of India is mixture of Aryans, Dravidians. Mongolians and scythians. Ethically all people are heterogeneous. It is the unity of culture that binds the people of Indian peninsula from one end to the other. Dr. Ambedkar said that, Caste in India mans an artificial chopping off of the population into fixed and definite units, each one prevented from fusing into another through the custom of endogamy.39 He also states that, the custom of sati, enforced widow-hood for life and child-marriage are the outcome of endogamy. And he concluded that, there was one caste to start with and that classes have become castes through imitation and excommunication.40 He stated further that, Chaturvarnya is the root cause of all its inequality and is also the parent of caste system and untouchability which are merely other forms of inequality. Therefore Dr Ambedkar, who believed that only by destroying the caste system could untouchability be destroyed.

Post Independence period

After independence for a partitioned India in 1947, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar became Law Minister in the Government of Jawaharlal Nehru and the drafter of the Constitution of India 1950. The Constitution states that no citizen should be discriminated against based upon religion, race, or caste among other attributes. And should not be denied access to and the use of public services. Constitutional Article No. 341 authorizes the President of India to specify Caste, races or tribes which shall for the purposeses of this constitution be

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writing and Speeches Vol. 1, 1989, Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, Bombay, Pp. 9. 40 Ibid, Pp. 22.

39

12

Chapter One

deemed to be Scheduled Castes Therefore the First Amendment to the Constitution passed in 1951 allowed the State to make special provision for advancement of socially and educationally backward classes of citizens of the Scheduld Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The SCs consist of those castes, which are included in a Schedule of the Constitution of India. The term Scheduled Castes is defined in Article 366 (24) of the Constitution of India as follows:

Scheduled Castes mean such castes, races or tribes or parts of or groups within such castes, races or tribes as are deemed under Article 341 (the President of India to specify the castes, races and tribes to be included in the list of Scheduled Castes in relation to a particular State or Union Territory, once such a list is notified with respect to any State or Union Territory.) to be Scheduled Castes for the purpose of this Constitution.

However, this is not the standard definition of Scheduled Castes. The Constitution (Scheduled Castes) order 1950 and 1951 The number of castes scheduled in the order of 1950 and 1951 increased to 821 (actually 927 castes) of them, only 22 (actually 25 castes) were considered scheduled for a part of the States. The Constitution Scheduled Castes, order 1956 The number of castes notified as SCs under the orders of 1956 shot up to 1119 (actually, 1590 castes). A large number of them, as many as 704 (actually 1048 castes) were considered scheduled for a part of the States. This was because of merger of areas from the neighboring states and amalgamation of parts B and C States with part A State for formation of linguistic States in India in 1956. The orders issued between 1956 and 1976 for the newly created States like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Tripura, Manipur, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, and union Territories like Goa, Daman and Diu, Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Pondicherry listed 376 (actually 633 castes) SCs. In the 1976 order 941 (actually 1492 castes) castes appeared. In 1976 the lists were amended mainly to remove area restorations in respect of most of the SCs. In the 1976 order there were only 25 (actually 27 castes) Castes, which were considered Scheduled for a part of the States.

Introduction

13

The 1976 order did not cover the State of Jammu and Kashmir and the Union Territories of Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Daman and Diu, Chandigarh, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Delhi and Pondichery, which were guided by the earlier orders. The number of Castes considered Scheduled in relation to these States/Union Territories was 141 (actually 200 castes). So, the total number of SCs in the States/Union Territories in 1976 was 941 (actually 1492) plus 141 (actually 200 castes) total 1082 (actually 1692 castes). [For the details about actual number of castes, given in the brackets, Please see Chatterjee S.K. (1996)] After 1976 some orders were issued by the Government of India,41 which substantially enlarged the number of castes grouped within, by adding more castes as equivalent names and synonyms and sub-castes / tribes of existing SCs and STs in different States. Regarding the criterion the point made by Ram Vilas Paswan needs to be noted. Paswan, who was the Union Minister of Welfare and Labour (May 1990) made the remark, while stating the objects and reasons for proposing to include Buddhist converts of SCs background in the list of SCs. He said,

Neo Buddhist is a religious group, which came into existence in 1956 as a result of a wave of conversion of the SCs under the leadership of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. Because of Converting to Buddhism, they became ineligible for statutory concessionsvarious demands have been made for all the existing concessions and facilities available to the SCs to them also on the ground that change of religion has not altered their social and economic condition. As they objectively deserve to be treated as SCs for the purpose of various reservations. It is proposed to amend the Presidential Orders to include them therein.42

Therefore in May, 1990 the amendment was passed by Indian Parliament and therefore the ex-Mahar converted to Buddhism is called as Buddhists. The Buddhists also get the same concessions along with the SCs belonging to the Hindu and Sikh religions. 43 The census of India 1991, shows the list of 499 communities of SCs, the SCs population constitutes about 16 percent of the total population in

Chatterjee S. K., 1996, The Scheduled Castes in India, Vol III, Gyan Publishing House, New Delhi, P.p.1095-1097. 42 Kananaikil Jose, 1993, Scheduled Caste converts in search of Justice, Constitution (Scheduled Castes) orders (Amendment Bill. 1990, PartIII, New Delhi, Pp.7778). 43 Massey James, 1998, Op. Cit, Pp. 60.

41

14

Chapter One

India. 21 communities out of 499 are either clubbed or merged with their respective synonyms. As a result a list 478 communities, the numerically dominant communities, are in each district. Therefore the survey44 has projected 220 communities in all over India. (SCs population is not recorded in Nagaland, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Lakshdadeep; district wise population of the SCs is not reported in Jammu and Kashmir.). According to the 2001 census the total population of SCs of India is 1,66,635,700 and 16.2 per cent of the total population of India.45 The Table No. 1.1 shows detailed SC population in a State-wise order in various census reports. (For the details about the SC population in Maharashtra State, See Chapter No. 4 and State wise Scheduled Castes list see the Appendix No. 1.) The Constitution of India offered special provisions for the SCs in education, employment and politics. Article 46, for instance, declares The State shall promote, with special care the educational and economical interests of the weaker sections of the people and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and shall protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.

Caste and occupation

However, the caste system is one of the unique features of Indian social structure and social life. On the one hand, the term is used to describe in the broadest sense, the total system of social stratification particular to India and on the other hand, it is used to denote about three distinct aspects of this total system, i. e.( i.)Varna,( ii) Jati and (iii) Gotra. Varna is not the same thing as jati but it represents the four-fold division (or groups) of society. Many Indian and foreign scholars devoted to caste study as Risley,46 Hutton,47 Bougle Celestin48 etc. The Indian scholars Majumdar and Madan,49 Ketkar,50 Karve,51 Beteille,52 Ghurye53 studied the caste structure

44

India: Scheduled Castes, 2003, Anthropological survey of India, Ministry of Tourism and culture, Govt, of India, Kolkatta, Pp. 5. 45 www.censusofindia. 46 Risley H. H., 1891, The tribes and castes of Bengal, Culcutta. 47 Hutton J. H., 1946, Op.Cit. 48 Bougle Celestion, 1908, Essais sur le regime des castes, Alcon, Paris. 49 Majumdar and Madan, 1956, Introduction to social Anthropology, Asia Publishing House, Delhi.

Introduction

15

in India. About the caste and occupation Ibbetson54 views that the fundamental idea, which lies at the root of the institution in its inception, was the hereditary nature of occupation. Toynbee55 says, The Depressed classes of India are typical example of Internal Proletariat, namely people who are in the society but not of the society. Srinivas defines caste, as a hereditary endogamous localized group having a traditional association with an occupation and is graded in hierarchy depending on the occupation though agriculture is common (in villages) to all castes from Brahmins to untouchables.56 Dumont views that, The caste system comprises the specialisation and interdependence of the constituent groups.57 Karve 58 reviews that, association between caste and occupational structure closest by identifying some of the groups of occupational specialists and some caste designations indicating their occupations. However there are two conflicting views about the relationship between the caste system and its occupational choice. Ghurye views that; the caste system not only assigns a definite occupation to each individual but also imposes certain restrictions on the change of occupation.59 On the other hand, the opposite view point is that the caste system has been dynamic in nature. Ghurye has tried to show, during the Middle Ages and after, that certain castes participated in a number of occupations.60 Hutton 61 also mentioned that, the castes are derived from tribal or racial elements.

Ketkar S.V., 1979, History of caste in India, Rawat Publications, Jaipur. Karve Iravati, 1961, Hindu society: an interpretation, 52 Beteille Andre, 1965, Caste, class and power, changing patterns of Stratification on a Tanjore village, University of California, Berkeley. 53 Ghurye G.S., 1959( 5th edition), Caste and race in India, Popular Prakashan, Bombay. 54 Ibbetson Denzil Charles Jelf, 1916, Punjab Castes, Philadelphia, U.S.A Pp.2. 55 Toynbee A.J., 1949, A study of History in D.C. Somorwell (Edit) Abridgement of Vol. I to VI, Oxford University Press, London, P.p.375. 56 Srinivas M. N., 1952, Religion and society among the coorgs of south India, Oxford University Press, P.p.32. 57 Dumont Louis, 1966, Homo Hierachicus, Vikas Publications, Banglore, Pp.92. 58 Karve Iravati, 1958, What is Caste? Caste and occupation, The Economic Weekly, Vol. X No. 12, Pp. 401-407. 59 Hutton J. H., 1946, Pp. 122-24, Abbe J. Dubbouis, 1897, Ollott massion, 1944, Pp. 655 60 Ghurye G. S., 1950, Caste and class in India, The Popular Prakashan Bombay, Pp. 15-17. 61 Hutton J.H., 1981 (sixth print), Caste in India, Oxford University Press, Delhi, P.p.2.

51

50

16

Chapter One

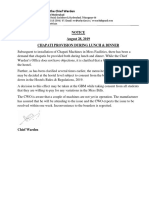

Table No. 1.1. Percentage of Scheduled Castes to Total Population According to 1971, 1981, 1991, 2001 Census

1981 Total SC % of SCs Population Population of Total Population 7,961,730 14.87 10,142,368 14.51 2,438,297 7.15 2,464,012 19.07 1,053,958 24.62 497,363 8.26 5,595,353 2,549,382 7,358,533 4,479,763 17,753 5,492 135 3,865,543 4,511,703 5,838,879 18,281 8,881,295 310,384 15.07 10.02 14.10 7.14 1.25 0.41 0.03 14.66 26.87 17.04 5.78 18.35 15.12 7,369,279 2,886,522 9,626,679 8,757,842 37,105 9,072 691 5,129,314 5,742,528 7,607,820 24,084 10,712,266 451,116 16.38 9.91 14.54 11.09 2.1 0.51 0.10 16.20 28.31 17.28 5.92 19.17 16.36 1991 Total SC % of SCs Population Population of Total Population 10,592,066 15.92 1,659,412 7.40 12,571,700 14.55 3,060,358 7.40 3,250,933 19.74 1,310,296 25.33 N.A. N.A. 2001 Total SC % of SCs Population Pop. of Total Population 12,339,496 16.2 1,825,949 6.9 13,048,608 15.7 3,592,715 7.1 4,091,110 19.3 1,502,170 24.7 770,115 7.6 8,563,930 3,123,941 9,155,177 9,881,656 60,037 11,139 272 6,082,063 7,028,723 9,694,462 27,165 11,857,504 555,724 16.2 9.8 15.2 10.2 2.8 0.5 0.0 16.5 28.9 17.2 5.0 19.0 17.4

State /UT

Total SC Population

Andhra Pradesh Assam Bihar Gujarat Haryana Himachal Pradesh Jammu and Kashmir Karnataka Kerala Madhya Pradesh Maharashtra Manipur Meghalaya Mizoram Nagaland Orissa Punjab Rajasthan Sikkim Tamil Nadu Tripura 13.14 8.30 13.09 6.00 1.53 0.38 0.02 15.09 24.71 15.82 4.53 17.76 12.39

1971 % of SCs Population of Total Population 5,774,548 13.27 7,950,652 14.11 1,825,432 6.84 1,895,933 18.89 769,572 22.24 381,277 8.26

3,850,034 1,772,168 5,453,690 3,025,761 16,376 3,887 82 3,310,854 3,348,217 4,075,580 9,502 7,315,595 192,860

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- We Don't Eat Our: ClassmatesDocument35 pagesWe Don't Eat Our: ClassmatesChelle Denise Gumban Huyaban85% (20)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Chapter 9 MafinDocument36 pagesChapter 9 MafinReymilyn SanchezNo ratings yet

- Merry Almost Christmas - A Year With Frog and Toad (Harmonies)Document6 pagesMerry Almost Christmas - A Year With Frog and Toad (Harmonies)gmit92No ratings yet

- Science of Happiness Paper 1Document5 pagesScience of Happiness Paper 1Palak PatelNo ratings yet

- Amet 12017Document14 pagesAmet 12017Klv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Should Caste Be Included in the CensusDocument3 pagesShould Caste Be Included in the CensusKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ambedkar's Vision of Economic Development and Social Justice Challenges India's Neoliberal ReformsDocument3 pagesDr. Ambedkar's Vision of Economic Development and Social Justice Challenges India's Neoliberal ReformsKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Anjali Rajoria-What It Means To Be Brahmin DalitDocument4 pagesAnjali Rajoria-What It Means To Be Brahmin DalitKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- 60 Years of Indian Republic: DR - Ambedkar and India's Neoliberal Economic Reforms. - Prof - Venkatesh AthreyaDocument3 pages60 Years of Indian Republic: DR - Ambedkar and India's Neoliberal Economic Reforms. - Prof - Venkatesh AthreyaKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth, Democracy and (Post-) Modernity: The Contradiction Between Growth and Development Seen From The Dalit Point of ViewDocument6 pagesCommonwealth, Democracy and (Post-) Modernity: The Contradiction Between Growth and Development Seen From The Dalit Point of ViewKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- AMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNDocument3 pagesAMBROSE PINTO-Caste - Discrimination - and - UNKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- A K VERMA-Samajwadi - Party - in - Uttar - PradeshDocument6 pagesA K VERMA-Samajwadi - Party - in - Uttar - PradeshKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International AffairsDocument7 pagesThe Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International AffairsKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Office of The Chief Warden: Prof. CR Rao Road, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, Telangana-46 WWW - Uohhostels.inDocument4 pagesOffice of The Chief Warden: Prof. CR Rao Road, Gachibowli, Hyderabad, Telangana-46 WWW - Uohhostels.inKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Pondicherry University Faculty Recruitment 2019Document4 pagesPondicherry University Faculty Recruitment 2019Harish KiranNo ratings yet

- AppliDocument2 pagesAppliSumit RoyNo ratings yet

- 05 May 2016Document68 pages05 May 2016Klv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Political Science Paper-IIDocument23 pagesPolitical Science Paper-IIKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Math Puzzles and GamesDocument130 pagesMath Puzzles and GamesDragan Zujovic83% (6)

- Current General KnowledgeDocument20 pagesCurrent General KnowledgeKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- HowtoWriteResearchProposals PDFDocument3 pagesHowtoWriteResearchProposals PDFKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Ecoincarceration Walking With The ComradesDocument3 pagesEcoincarceration Walking With The ComradesKlv SwamyNo ratings yet

- Are Moral Principles Determined by SocietyDocument2 pagesAre Moral Principles Determined by SocietyKeye HiterozaNo ratings yet

- Policy Guidelines On Classroom Assessment K12Document88 pagesPolicy Guidelines On Classroom Assessment K12Jardo de la PeñaNo ratings yet

- Network Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsDocument12 pagesNetwork Monitoring With Zabbix - HowtoForge - Linux Howtos and TutorialsShawn BoltonNo ratings yet

- Dreams and Destiny Adventure HookDocument5 pagesDreams and Destiny Adventure HookgravediggeresNo ratings yet

- Chapter One - Understanding The Digital WorldDocument8 pagesChapter One - Understanding The Digital Worldlaith alakelNo ratings yet

- Neandertal Birth Canal Shape and The Evo PDFDocument6 pagesNeandertal Birth Canal Shape and The Evo PDFashkenadaharsaNo ratings yet

- FunambolDocument48 pagesFunambolAmeliaNo ratings yet

- 7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJDocument2 pages7 Years - Lukas Graham SBJScowshNo ratings yet

- Role of TaxationDocument5 pagesRole of TaxationCarlo Francis Palma100% (1)

- VIII MKL Duet I Etap 2018 Angielski Arkusz Dla PiszącegoDocument5 pagesVIII MKL Duet I Etap 2018 Angielski Arkusz Dla PiszącegoKamilNo ratings yet

- Ca Final DT (New) Chapterwise Abc & Marks Analysis - Ca Ravi AgarwalDocument5 pagesCa Final DT (New) Chapterwise Abc & Marks Analysis - Ca Ravi AgarwalROHIT JAIN100% (1)

- Onsemi ATX PSU DesignDocument37 pagesOnsemi ATX PSU Designusuariojuan100% (1)

- Handout of English For PsychologyDocument75 pagesHandout of English For PsychologyRivan Dwi AriantoNo ratings yet

- Blind and Visually ImpairedDocument5 pagesBlind and Visually ImpairedPrem KumarNo ratings yet

- 2 NDDocument52 pages2 NDgal02lautNo ratings yet

- Table Topics Contest Toastmaster ScriptDocument4 pagesTable Topics Contest Toastmaster ScriptchloephuahNo ratings yet

- Report-Picic & NibDocument18 pagesReport-Picic & NibPrincely TravelNo ratings yet

- 4th Singapore Open Pencak Silat Championship 2018-1Document20 pages4th Singapore Open Pencak Silat Championship 2018-1kandi ari zonaNo ratings yet

- Vinzenz Hediger, Patrick Vonderau - Films That Work - Industrial Film and The Productivity of Media (Film Culture in Transition) (2009)Document496 pagesVinzenz Hediger, Patrick Vonderau - Films That Work - Industrial Film and The Productivity of Media (Film Culture in Transition) (2009)Arlindo Rebechi JuniorNo ratings yet

- PRINCE2 Product Map Timeline Diagram (v1.5)Document11 pagesPRINCE2 Product Map Timeline Diagram (v1.5)oblonggroupNo ratings yet

- Think Like An EconomistDocument34 pagesThink Like An EconomistDiv-yuh BothraNo ratings yet

- Assessment Explanation of The Problem Outcomes Interventions Rationale Evaluation Sto: STO: (Goal Met)Document3 pagesAssessment Explanation of The Problem Outcomes Interventions Rationale Evaluation Sto: STO: (Goal Met)Arian May MarcosNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Risks of Dexamethasone in Noncardiac Surgery: Clinical Focus ReviewDocument9 pagesBenefits and Risks of Dexamethasone in Noncardiac Surgery: Clinical Focus ReviewAlejandra VillaNo ratings yet

- Ais 301w Resume AssignmentDocument3 pagesAis 301w Resume Assignmentapi-532849829No ratings yet

- Marwar Steel Tubes Pipes StudyDocument39 pagesMarwar Steel Tubes Pipes Studydeepak kumarNo ratings yet

- Comprehension Used ToDocument2 pagesComprehension Used TomarialecortezNo ratings yet