Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Organizational Culture & Change Management

Uploaded by

sweetlittlegirl_92Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Organizational Culture & Change Management

Uploaded by

sweetlittlegirl_92Copyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Management Studies 42:2 March 2005 0022-2380

The Impact of Organizational Culture and Reshaping Capabilities on Change Implementation Success: The Mediating Role of Readiness for Change

Renae A. Jones, Nerina L. Jimmieson and Andrew Grifths

Queensland University of Technology; The University of Queensland; The University of Queensland

It was hypothesized that employees perceptions of an organizational culture strong in human relations values and open systems values would be associated with heightened levels of readiness for change which, in turn, would be predictive of change implementation success. Similarly, it was predicted that reshaping capabilities would lead to change implementation success, via its effects on employees perceptions of readiness for change. Using a temporal research design, these propositions were tested for 67 employees working in a state government department who were about to undergo the implementation of a new end-user computing system in their workplace. Change implementation success was operationalized as user satisfaction and system usage. There was evidence to suggest that employees who perceived strong human relations values in their division at Time 1 reported higher levels of readiness for change at pre-implementation which, in turn, predicted system usage at Time 2. In addition, readiness for change mediated the relationship between reshaping capabilities and system usage. Analyses also revealed that preimplementation levels of readiness for change exerted a positive main effect on employees satisfaction with the systems accuracy, user friendliness, and formatting functions at post-implementation. These ndings are discussed in terms of their theoretical contribution to the readiness for change literature, and in relation to the practical importance of developing positive change attitudes among employees if change initiatives are to be successful.

Address for reprints: Nerina L. Jimmieson, School of Psychology, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, 4072, Australia (n.jimmieson@psy.uq.edu.au).

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005. Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ , UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

362 INTRODUCTION

R. A. Jones et al.

While the failure of planned organizational change may be due to many factors, few are so critical as employees attitudes towards the change event. Schein (1987, 1988, 1999) has addressed the failure of organizational change programmes by arguing that the reason so many change efforts run into resistance or outright failure is traceable to the organizations inability to effectively unfreeze and create readiness for change before attempting a change induction. In this respect, organizations often move directly into change implementation before the individual or the group to be changed is psychologically ready. From this observation, researchers in the area of organizational change have begun to direct their attention to a range of variables that may foster change readiness among employees, as well as examining the extent to which readiness for change leads to change implementation success. The notion of readiness for change can be dened as the extent to which employees hold positive views about the need for organizational change (i.e. change acceptance), as well as the extent to which employees believe that such changes are likely to have positive implications for themselves and the wider organization (Armenakis et al., 1993; Holt, 2002; Miller et al., 1994). Other approaches to the study of readiness for change have focused on whether employees perceive that their organization and its members are ready to take on largescale change initiatives (Eby et al., 2000). In the present study, it is proposed that organizational culture and reshaping capabilities are inuential in shaping how ready employees feel about impending organizational change. The extent to which employees perceptions of readiness for change are predictive of better change outcomes also was addressed.

Predictors of Readiness for Change Several studies exist within the organizational change literature that have investigated employee resistance factors to organizational change (e.g. Armenakis et al., 1993, 1999; Martinko et al., 1996; Miller et al., 1994; Ogbonna and Wilkinson, 2003; Wanberg and Banas, 2000). Typically, these studies have focused on characteristics associated with the individual. Such characteristics usually come from the psychological literature and have focused on personality attributes (e.g. openness to change), cognitive processes (e.g. self-efcacy beliefs), and the extent to which employees feel that they have had access to external coping resources to help them to deal with the stressful nature of organizational change (e.g. the provision of timely information and opportunities to be involved in relevant decision-making). For example, Miller et al. hypothesized that employees who felt that they had received high-quality information about the impending changes would also report high levels of readiness for change, a proposition that was supported for 168 employees in a national insurance company about to introduce team-based methods of working.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

363

Similarly, Wanberg and Banas found that pre-implementation measures of several change-specic variables (which included self-efcacy, information provision, and active participation) were predictive of readiness for change (assessed two months after the collection of the rst wave of data) for 130 employees working in a public housing association undergoing large-scale restructuring. However, studies examining the role of employees perceptions of the organizational environment in fostering readiness for change perceptions are scarce. This is inconsistent with the organizational change literature that has proposed that an examination of organizational culture and organizational capabilities (as they relate to organizational change) is essential for understanding the processes that lead to successful change implementation (see Cummings and Worley, 2001; Detert et al., 2000; Paton and McCalman, 2000). Some preliminary empirical evidence in support of the potential role of broader contextual variables in developing positive change attitudes was provided by Eby et al. (2000). They found that employees who rated their division as having exible policies and procedures were more likely to evaluate their organization and the people working there as being more responsive to change. In light of research of this nature, the rst aim of present study was to test the role of organizational culture in the prediction of employees levels of readiness for change. In addition, Beckard and Harris (1987) believe that readiness for change should be examined in relation to organizational capabilities, proposing a matrix to examine the relationship between existing organizational capabilities and levels of readiness for change. They state that an assessment of organizational capabilities will assist organizations to focus on specic areas that need to be addressed in order to create the critical energy for change to occur. In light of this idea, a second aim of the present study was to test the extent to which employees who rate their workplace as having adequate organizational capabilities relevant to the management of change (i.e. reshaping capabilities) also will report higher levels of personal change readiness. Organizational Culture There is no clear consensus of an organizational culture denition (see Howard, 1998; Zammuto et al., 2000). However, many researchers in the area have adopted Scheins (1990) three dimensional view of organizational culture consisting of assumptions, values, and artefacts. Assumptions are the taken-for-granted beliefs about human nature and the organizational environment that reside deep below the surface. Values are the shared beliefs and rules that govern the attitudes and behaviours of employees, making some modes of conduct more socially and personally acceptable than others (Rokeach, 1973). Artefacts are the more visible language, behaviours, and material symbols that exist in an organization. Given that values are considered to be so central to understanding an organizations culture (Ott, 1989) and they are also seen as a reliable representation of organizational

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

364

R. A. Jones et al.

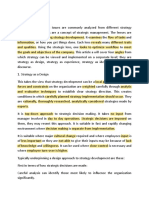

culture (Howard, 1998), the measurement of organizational culture has typically focused on values. Indeed, Quinn and his colleagues used the notion of values to develop the Competing Values Framework (CVF) of organizational culture (see Quinn, 1988; Quinn and Hall, 1983; Quinn and Kimberly, 1984; Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1981, 1983). The CVF explores the competing demands within an organization on two axes. In this respect, organizations are classied according to whether they value exibility or control in organizational structuring (i.e. exibility versus control). In addition, organizations differ in terms of whether they adopt an inward focus towards their internal dynamics or an external focus towards the environment (i.e. internal versus external). As a consequence, four quadrants, or culture types, are formed. The CVF and the general characteristics of each quadrant are illustrated in Figure 1. An organizational culture emphasizing human relations values aims to foster high levels of cohesion and morale among employees through training and development, open communication, and participative decision-making. An open systems orientation also values high employee morale but places more of an emphasis on innovation and development. This is achieved by fostering adaptability and readiness, visionary communication, and adaptable decision-making. An organizational culture with high internal process values strives for stability and control attained through formal information management, precise communication, and data-based decision-making. Lastly, an organizational culture possessing a rational goal orientation promotes efciency and productivity, typically gained through goal-setting and planning, instructional communication, and centralized decision-making. The latter two culture types tend to have lower levels of cohesion and morale among employees. Based on these descriptions, it would appear that each type of organizational culture is mutually exclusive. As pointed out by Quinn, however, all four culture types can exist in a single organization, although some values are likely to be more dominant than others (see Quinn, 1988; Quinn and Cameron, 1983; Quinn and Kimberly, 1984; Quinn et al., 1991). Indeed, there is a growing body of empirical evidence to suggest that organizations simultaneously emphasize multiple value orientations, as dened by the CVF (e.g. Buenger et al., 1996; Howard, 1998; Kalliath et al., 1999; Zammuto and Krakower, 1991). Organizational Culture and Readiness for Change As noted earlier, perceptions of readiness for change may differ within an organization and this has been attributed not only to individual differences, but also to cultural memberships that polarize the beliefs, attitudes, and intentions of members (Armenakis et al., 1993). To illustrate, Zammuto and OConnor (1992) ascertained that organizational cultures with exible structures and supportive climates were more conducive to the successful implementation of advanced manufacturing technologies than more mechanistic organizations characterized by

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

Flexibility

365

Human relations

Open systems

Ends * cohesion and morale

Ends * innovation and development

Means * training and development * open communication * participative decision-making Internal

Means * adaptability and readiness * visionary communication * adaptable decision-making External

Internal process

Rational goal

Ends * stability and control

Ends * efficiency and productivity

Means * information management * precise communication * data-based decision-making

Means * goal-setting and planning * instructional communication * centralized decision-making

Control

Figure 1. The Competing Values Framework Source: Adapted from Quinn, R. E. and Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: toward a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29, 36377.

inexibility and control. In light of this nding, it was proposed, in the present study, that employees who perceive their workplace to be dominant in either human relations values or open systems values are more likely to hold positive views towards organizational change. Indeed, a human relations orientation is characterized by the training and development of its human resources, which may relate to an employees condence and capability to undertake new workplace challenges. Also, the dynamic and innovative nature of the open systems culture type would suggest that employees who perceive their organizational culture to be an open system are more likely to possess positive attitudes towards organizational change. It is also important to note that factors already empirically demonstrated

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

366

R. A. Jones et al.

to be associated with readiness for change (e.g. communication and employee involvement) are characteristic of the human relations and open systems culture types (see Zammuto and Krakower, 1991). Therefore, this research seeks to examine the extent to which employees who perceive their division as having characteristics in line with either the human relations culture or the open systems culture perceive higher levels of readiness for change prior to the implementation of a specic change event than employees who rate their organizational culture as being low on these two types of value orientations. Reshaping Capabilities The concept of organizational capabilities has its foundations in the competitive advantage literature (Teece et al., 1997). The competitive advantage concept is grounded in the resource-based perspective that views an organization as a unique bundle of heterogeneous resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1998). According to Sharma and Vredenburg (1998), the resource-based view implies that an organizations competitive strategies and performance depend signicantly upon organization-specic resources and capabilities. Teece and Pisano (1994) assert that organizational capabilities should be discussed in association with organizational and managerial processes, the current endowment of technology and intellectual property, and the strategic alternatives that are necessary for sustained business performance. Meyer and Utterback (1993) add that higher levels of these capabilities are associated with sustained success, be it in terms of product development, nancial performance, or employee satisfaction. Researchers such as Teece and Pisano (1994) believe that leading organizations in the current and future global markets will be those that can demonstrate timely responsiveness to effectively coordinate and redeploy external and internal competencies. The concept of organizations being exible in manipulating current capabilities and developing new ones also has been acknowledged by several researchers (e.g. Penrose, 1959; Teece, 1982; Wernerfelt, 1984). However, only more recently have researchers begun to focus on capabilities needed to respond to shifts in the internal and external environment, more concisely, the capabilities needed for change (Teece and Pisano, 1994). The capabilities required for successful change have been specically addressed by Teece and his colleagues who refer to these capabilities as dynamic capabilities (Teece and Pisano, 1994; Teece et al., 1997). Dynamic capabilities refer to the capacity to renew competences so as to achieve congruence with the changing business environment. Turner and Crawford (1998) also have discussed organizational capabilities needed for change. Turner and Crawford differentiated between operational capabilities and reshaping capabilities. Operational capabilities are required for sustaining everyday performance. They suggest that strong operational capabilities do not generally help the organization to manage change effectively. Indeed, the

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

367

capabilities needed to achieve change implementation success are very different from those required for current business performance. In an attempt to dene reshaping capabilities more precisely, Turner and Crawford proposed a taxonomy consisting of engagement, development, and performance management capabilities. Engagement is based on informing and involving organizational members in an attempt to encourage a sense of motivation and commitment to the goals and objectives of the organization. Development involves developing all resources and systems needed to achieve the organizations future directions. Proactively managing the factors that drive the organizations performance to ensure it consistently and effectively achieves the intended change is the capability Turner and Crawford label performance management. Miller and Chen (1994) claimed that successful change implementation will be the result of the development of reshaping capabilities such as these. Indeed, in analyses of 243 cases of organizational change, Turner and Crawford (1998) found that, as the strength of reshaping capabilities rises, so too do the rates of change implementation success. Effective change outcomes are undermined when organizations have low levels of reshaping capabilities. More specically, they found that there was a strong positive relationship between reshaping capabilities and change implementation success. Interestingly, the impact of engagement and development capabilities upon current business performance was much weaker. However, performance management capabilities were identied as being important for current business performance. Overall, Turner and Crawford concluded that reshaping capabilities are needed whenever organizational change is needed. However, the potential to draw strong conclusions about these ndings is limited, given that few studies have examined the direct relationship between reshaping capabilities and change implementation success. Furthermore, no studies to date have examined the extent to which reshaping capabilities help to foster a sense of readiness for change among employees. Indeed, readiness for change perceptions may be the mediating variable that helps to explain the positive relationship between reshaping capabilities and change implementation success. Reshaping Capabilities and Readiness for Change Beckard and Harris (1987) have discussed the link between reshaping capabilities and readiness for change in their research on organizational transitions. They argued that it is essential to determine levels of readiness for change, which is essentially an analysis of employees attitudes towards the change event. However, in addition to the attitudes of those employees involved, they argued that the capability of the organization to effectively manage the changes should also be examined. Whereas readiness for change involves the motivation and willingness of the employees, reshaping capabilities involves the knowledge, skills, and abilities of the

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

368

R. A. Jones et al.

organization as a whole to carry out the necessary requirements for successful change implementation (Beckard and Harris, 1987). It is suggested in the present study that an organization or division who is equipped to effectively manage organizational change is doing so via its effects on individual perceptions of readiness for change. Again, it is important to note that some of the change management strategies known to be important in creating readiness for change (e.g. communication and involvement) are characteristic of an organization who is engaging and developing its employees. Therefore, it was the aim of this research to test whether employees who perceive their division as being ready for change (i.e. possessing reshaping capabilities) will also perceive higher levels of personal readiness for change prior to the implementation of a specic change event. Linking Readiness for Change to Change Implementation Success Readiness for change is often described and used as the dependent variable in both conceptual and empirical studies (e.g. Armenakis et al., 1993; Eby et al., 2000; Miller et al., 1994). Readiness for change has rarely been considered as a mediating variable between change management strategies and change implementation success. This is with the exception of a study conducted by Wanberg and Banas (2000) who tested a mediating model of readiness for change. As noted earlier, they proposed that a range of variables (e.g. self-efcacy, information provision, active participation) would foster readiness for change which, in turn, would be predictive of employee adjustment (e.g. job satisfaction, work irritation, intention to quit, and actual turnover). Several of the pre-implementation measures were predictive of readiness for change perceptions. There also was some evidence for the main effects of readiness for change on work irritation, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Given that many of the predictor variables were not related to the indicators of employee adjustment, tests for a mediational relationship between the predictor variables, readiness for change, and employee adjustment were not possible. Weak support for the mediating role of readiness for change in this study may be attributed to the general nature of the employee adjustment measures which did not specically address outcomes associated with the restructuring taking place in the organization. Consequently, the present study will address this issue by focusing on indicators of change implementation success that are specic to the nature of the organizational changes. In this respect, the present study examined the mediating role of readiness for change in the relationship between change management strategies and change implementation success for a sample of employees undergoing the implementation of a new end-user computing system in their workplace. The outcome of implementing a new information system is not just a change in technology, but also a change in structures, duties, tasks, and personnel. In addition, Bjorn-Anderson (1988) and Hirscheim and Newman (1988) claim that

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

369

managers and users of information systems often remain resistant throughout the implementation process, despite the disappearance of most technical barriers. Understanding and creating the workplace conditions under which employees embrace such challenges remains a high-priority research issue (Vankatesh and Davis, 2000). Based on the previous discussion, it is argued that readiness for change is an important mediating variable to consider in understanding the effectiveness of change programs and, similarly, will be a relevant concept to consider in relation to the implementation of a new information system. As a consequence, the present study will utilize the context of information system implementation for studying the relationships among organizational culture, reshaping capabilities, and readiness for change in the prediction of change implementation success. In the present study, change implementation success was operationalized as user satisfaction and system usage, both of which are prime criteria of successful information system implementation (Guimaraes et al., 1992; Lucas, 1973; Pinto, 1994; Santhanam et al., 2000). User satisfaction is dened by Ives et al. (1983) as the extent to which users believe the system meets their needs. Indeed, user satisfaction is probably the most widely used measure of success in this context (DeLone and McLean, 1992). The degree of system usage also is a frequently adopted measure of successful information system implementation (Haines and Petit, 1997; Lee et al., 1995; Lucas, 1975). System usage is dened by Lee et al. as the amount of effort expended by users interacting with the information system, or more simplistically, the amount of time per day spent utilizing the system. Together, user satisfaction and system usage provide a more complete picture of success than if either measure was utilized alone. The rst is based on beliefs and attitudes, whereas the second is based on behaviours (Haines and Petit, 1997). Working Hypotheses To summarize, rst, it was hypothesized that employees who perceive a human relations cultural environment within their division would report higher levels of user satisfaction and system usage (than employees who rate their organizational culture as being low on human relations values) and that this relationship would be mediated by their ratings of readiness for change (Hypothesis 1a). Second, it was predicted that employees who perceive an open systems cultural environment within their division would report higher levels of user satisfaction and system usage (than employees who rate their organizational culture as being low on open systems values) and that this relationship would be mediated by their change readiness perceptions (Hypothesis 1b). Lastly, it was hypothesized that employees who report high, rather than low, levels of reshaping capabilities within their division would also perceive heightened levels of readiness for change which, in turn, would be predictive of change implementation (Hypothesis 2). These hypotheses were tested in a temporal research design in which employees perceptions of organi Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

370

R. A. Jones et al.

zational culture, reshaping capabilities, and readiness for change were measured just prior to the introduction of a new end-user computing system in the workplace. The measures of user satisfaction and system usage were assessed in a second wave of data collection once the implementation process had been nalized.

METHOD Organizational Setting The context for this research was a state government department in Queensland, Australia about to implement an end-user computing system. The end-user computing system was an extension of the existing Human Resource Information System (HRIS) that was implemented a year prior, with the implementation of the HRIS affecting only the data entry personnel at that time. The implementation of the end-user computing system would affect all employees within the organization, as they would need to access the system for viewing payroll information, requesting annual leave, and applying for training courses. The implementation strategy was incremental, consisting of three pilot stages and then a roll-out to all employees. However, the implementation schedule was severely delayed due to a variety of technical problems. The implementation of the rst pilot group was close to 10 months behind schedule and consequently, the organization modied its strategy to undertake only one pilot programme before devolving the system to all employees. Considering this, the organization was eager to undertake a comprehensive evaluation of the pilot process to assist in identifying the most effective and efcient devolution process for the system to all employees.

Research Design As noted earlier, a temporal research design was utilized in which the predictor variables (i.e. organizational culture, reshaping capabilities, and readiness for change) were measured at Time 1 (T1), just prior to the implementation of the organizational changes described above. In order to examine the extent to which the predictor variables had any effects on change implementation success (i.e. user satisfaction and system usage), the outcome measures were assessed at Time 2 (T2), approximately ve weeks after the collection of the T1 data. At this point in time, employees had been using the new HRIS for a period of one month. A strength of this research design was the temporal separation of the predictor and outcome variables, all of which were self-report. This approach helps to minimize the effects of common method variance that can emanate from the inuence of priming, social desirability bias, consistency effects, and unstable occasion factors, such as mood states (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). It is important to note, however, that

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

371

although this research design goes some way to reducing the effects of common method variance, it does not permit inferences of causality (Zapf et al., 1996). Sampling Procedure and Characteristics Questionnaires were posted to all employees in the pilot group (N = 572) via the organizations internal dispatch system. Employees were asked to return the questionnaire directly to the researchers in the reply-paid envelope provided. Despite a range of tactics to maximize response rates, only 156 employees provided data at T1, representing a response rate of 27 per cent. Although less than optimal, this response rate is acceptable for mail questionnaires (Cavana et al., 2000). Cavana et al. comment that small response rates do not necessarily decrease the studys scientic value, but its generalizability is restricted. In an attempt to demonstrate that the T1 sample was representative of the population in terms of its demographic characteristics, a comparison was made between the 156 employees who returned the rst questionnaire and the pilot group as a whole on gender and organizational unit. These were the only descriptive information available about the pilot group. In the pilot group, the percentage of males and females was 53 per cent and 47 per cent, respectively. These proportions are comparable to the gender breakdown in the T1 sample (males = 52 per cent; females = 48 per cent). In addition, the proportion of T1 employees across each of the organizational units (ten groups representing different job functions in the agency) was found to be relatively consistent with the corresponding breakdown in the pilot group. At T2, 98 employees returned the follow-up questionnaire. However, employees who completed both the T1 and T2 questionnaires amounted to 43 per cent of the T1 sample (n = 67). In the present study, analyses were performed only for employees who provided data at both points in time. The T2 sample consisted of a relatively equal proportion of male (41 per cent) and female respondents (57 per cent; 2 per cent of employees failed to specify their gender). Employees ranged in age from 20 to 65 years, with a mean of 37.13 years (SD = 11.08). Four per cent of the sample did not provide data about their age. The majority of participants were either administrative ofcers (58 per cent) or professional ofcers (38 per cent), whereas 4 per cent of employees occupied other roles in the organization. It is important to note that a series of t-tests established that employees who did not respond at T2 did not differ signicantly from employees who provided data at both points in time on the variables of gender, age, organizational culture, reshaping capabilities, and readiness for change. Measures Multi-item scales were used to ensure adequate measurement of each variable. For the same reason, previously established scales were used where suitable. Reliabil Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

372

R. A. Jones et al.

ity of the measures was assessed using Cronbachs (1951) alpha coefcient, and these are presented in Table I. As can be seen from this table, all measures used in the present research were considered to have adequate internal consistency. Organizational culture. Organizational culture was assessed with a measure developed by Zammuto and Krakower (1991). This measure has been used in several studies examining organizational culture (e.g. Bradley and Parker, 2001; Gifford et al., 2002; Parker and Bradley, 2000). Based on the CVF, this instrument asks employees to indicate the extent to which their organization possesses characteristics associated with each of the four culture types (i.e. human relations, open systems, internal process, and rational goal) along ve dimensions. These dimensions include: (1) character (e.g. Organization A is a very personal place, very much like an extended family); (2) leadership (e.g. managers in Organization A are warm and caring, seeking to develop employees full potential); (3) cohesion (e.g. the glue that holds Organization A together is tradition and loyalty); (4) emphases (e.g. Organization A emphasizes human resources); and (5) rewards (e.g. Organization A distributes its rewards equally and fairly among its members). Respondents distributed 100 points across each of the four descriptive statements within each of the ve dimensions depending on how well they matched their division. Procedures for devising a competing values prole for each employee were then utilized. First, scores were adjusted in order to correct for any mathematical errors made by respondents. This ensured that the total score distributed across each of the four statements totalled 100. This was followed by averaging a respondents rating for each culture type across the ve dimensions. To illustrate, a respondents total human relations culture score was created by summing their responses to 1A, 2A, 3A, 4A, and 5A, and then dividing by ve. This process created an overall score on each type of organizational culture for each respondent. Reshaping capabilities. The notion of reshaping capabilities has received little empirical investigation (Turner and Crawford, 1998; see also Teece et al., 1997). Thus, the choice of instruments to measure reshaping capabilities is limited. Ten items were developed for use in the present study based on Turner and Crawfords taxonomy of engagement, development, and performance management. Items also were selected from a similar scale developed by Waldersee et al. (2003). Respondents were asked to indicate the existing strength or weakness of each capability for their division on a ve-point scale, ranging from 1 (very weak) to 5 (very strong). An example item is: The divisions ability to redistribute resources to cope with change. Readiness for change. Levels of readiness for change were measured with seven items designed to assess the extent to which employees were feeling positive about the

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

373

changes introduced by the new HRIS (adapted from items developed by Miller et al., 1994). Items asked employees if they considered themselves to be open or resistant to the changes, if they were looking forward to the changes in their work role, and if the changes would be for the better, particularly in relation to how they did their job. Participants responded on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Four items were reverse-scored due to negatively worded questions. User satisfaction. Levels of user satisfaction were measured with the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument (Doll and Torkzadeh, 1988). Consisting of 34 items, this instrument is designed to measure ve aspects of user satisfaction (i.e. accuracy, content, user friendliness, format, and timeliness). Participants responded to each item on a ve-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). To assess the multidimensional nature of the scale, responses to the items were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis using principal axis factoring and an orthogonal (varimax) rotation. This analysis was performed on the entire sample that returned surveys at T2 (n = 98). It is important to acknowledge that the results of the factor analysis to be reported should be interpreted with caution, given that the minimum requirement of ve cases per item was not met for this analysis (as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Thus, the items were rst tested to determine the adequacy of the sample size for the purpose of factor analysis. Tabachnick and Fidell recommend the use of Bartletts test of sphericity, particularly when there are fewer than ve cases per item. This test showed that the correlation matrix was not an identity matrix, indicating that some signicant correlations among the items existed ( c2 = 2762, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was relative high (0.85). Tabachnick and Fidell recommend values of 0.60 or above for good factor analysis. Based on these preliminary analyses, the factorability of the user satisfaction scale was considered to be favourable. The number of factors retained was determined by the number of eigenvalues greater than one. On this basis, eight factors were extracted, which accounted for 80 per cent of the variance. Initially, items that loaded below 0.40 or had factor loadings of 0.40 or above across two or more factors were eliminated (see Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). It also was appropriate to eliminate the third factor reecting timeliness because only two items remained once impure items were removed. As discussed by Mulaik (1972), failure to include three or more items per factor would result in situations where factors are indeterminate (see also Etezadi-Amoli and Farhoomand, 1991, for a discussion of this issue in relation to the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument). This process resulted in four usable factors for use in the present study. Three items were retained to measure satisfaction with accuracy (e.g. Are you satised with the accuracy of the system?). Five items

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

374

R. A. Jones et al.

formed the content scale (e.g. Does the system provide information that meets your needs?). Six items comprised the user friendliness scale (e.g. Is the system easy to use?). Lastly, four items loaded on the factor measuring satisfaction with the formatting properties of the HRIS (e.g. Do you think the systems output is presented in a useful format?). System usage. Measurement of system usage consisted of a single item (i.e. In a typical week, how many times do you utilize the system?). Responses were made on a ve-point scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time). This approach is consistent with other researchers who have measured system usage (e.g. Fuerst and Cheney, 1982; Lucas, 1973; Raymond, 1985). A second question asked respondents to specify the exact number of times they use the system in a typical week. The intercorrelation between these two questions was signicant, r = 0.51, p < 0.01, validating the criterion validity of the Likert-scale approach. As a result, the rst measure of system usage was used in subsequent analyses.

RESULTS Preliminary Data Analyses Descriptive data (means and standard deviations) and intercorrelations among each of the variables are displayed in Table I. Data for all four culture types has been provided to give a complete picture of the culture prole of the organization. As expected with ipsative data, there were statistically signicant relationships among each of the four culture types. Human relations culture and open systems culture were positively related to each other, r = 0.26, p < 0.05, whereas internal process culture and rational goal culture also were positively correlated, r = 0.24, p < 0.05. The human relations culture and open systems culture were both negatively correlated to the culture of internal process. Additionally, human relations culture and open systems culture were both negatively related to the culture of rational goal. It also should be noted that intercorrelations among accuracy, content, user friendliness, and format were high, which was expected as they are dimensions of the broader concept of user satisfaction. Given that the exploratory factor analysis provided support for a four-dimensional factor structure, these were retained as separate dependent variables in this study. Lastly, intercorrelations among user satisfaction and system usage were low to moderate, suggesting that these variables are empirically distinct. The effects of age and gender were investigated as these demographic characteristics have been reported to affect user satisfaction and system usage in computing environments. For instance, Howard (1986) found that age and computer anxiety were positively correlated with each other. Similarly, Zoltan and Chapanis (1982) found that youth was associated with more favourable attitudes towards

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

Table I. Descriptive data (means and standard deviations) and intercorrelations among the variables

Variables Age Gender Human relations culture Open systems culture Internal process culture Rational goal culture Reshaping capabilities Readiness for change User satisfaction accuracy User satisfaction content User satisfaction user friendliness 12. User satisfaction format 13. System usage 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. M 37.26 1.60 21.37 18.52 32.24 27.87 3.10 5.34 4.06 3.85 3.42 3.67 2.41 SD 11.60 0.49 12.65 11.45 18.10 11.77 0.68 1.10 0.77 0.90 0.95 0.90 0.74 1 -0.40** -0.04 -0.03 0.00 0.08 0.08 -0.05 0.03 0.11 0.01 0.11 -0.10 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

0.13 -0.06 -0.13 0.12 0.06 0.13 0.01 -0.01 -0.02 0.12 0.04 (0.72) 0.26* -0.61** -0.38** 0.30* 0.33** -0.06 -0.09 -0.06 -0.09 0.23 (0.87) -0.66** -0.29* 0.07 -0.06 -0.19 -0.06 -0.04 -0.01 -0.08

(0.82) 0.24* -0.21 -0.17 0.11 0.05 -0.06 -0.07 -0.05

(0.61) -0.06 -0.05 0.08 0.08 0.20 0.21 -0.09

(0.88) 0.33** -0.01 -0.09 0.08 -0.03 0.28*

(0.85) 0.26* 0.11 0.31* 0.31* 0.42**

(0.90) 0.71** 0.64** 0.65** 0.22

(0.94) 0.65** 0.72** 0.10

(0.94) 0.68* 0.35** (0.89) 0.14

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Notes: Cronbachs (1951) alpha coefcients for each of the variables are in parentheses along the main diagonal. p < 0.075; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

375

376

R. A. Jones et al.

computers. It also has been reported that although men often possess more computer-related skills, women are more likely to hold more positive perceptions about the benets of computers (Gutek and Bikson, 1985). As shown in Table I, age and gender were not signicantly correlated with any of the predictor or outcome variables assessed in this study. Furthermore, additional preliminary analyses with the use of hierarchical multiple regression demonstrated that when age and gender were statistically controlled (entered at Step 1), they did not alter any of the signicant ndings reported in this study. Thus, the hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed on the complete sample, regardless of age or gender. Data Analysis Overview Consistent with Kenny et al.s (1998) recommendations for the testing of mediated models involving continuously measured variables, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was employed (see also Baron and Kenny, 1986; James and Brett, 1984). It is important to note that the scoring method used to measure the four types of organizational culture as represented in the CVF produces ipsative data that are generally not appropriate for normative interpretation (Hicks, 1970). However, Hicks also notes that when one or more of the scales from the ipsative predictor set is deleted when the data are analysed, then the scores do not meet the criterion for pure ipsativity (p. 170). It was for these reasons that we did not develop and test hypotheses involving the internal process and rational goal quadrants of the CVF. Other studies also have used only two quadrants of the CVF in order to facilitate the appropriate use of multivariate statistical techniques (e.g. Shortell et al., 1995). Furthermore, the hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed separately for Hypotheses 1a (human relations culture) and 1b (open systems culture). In this way, the scores for these two types of organizational culture were not considered simultaneously, thereby reducing the impact of the dependency relationship that exists between them. Thus, a total of three sets of hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed on each of the ve dependent variables. One set of analyses examined the indirect effects of a human relations culture on change implementation success, via its effects on employees levels of readiness for change (Hypothesis 1a). The second set of analyses examined the indirect effects of an open systems culture on the four dimensions of user satisfaction and system usage, via its effects on employees change readiness perceptions (Hypothesis 1b). The nal set of analyses examined the extent to which reshaping capabilities predicted readiness for change, thereby heightening user satisfaction and system usage (Hypothesis 2). Baron and Kenny discuss four tests that need to be followed when establishing a mediated relationship among a set of variables. These four tests were conducted for each of the three hypotheses and are discussed below.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

377

Table II. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses involving employees perceptions of a human relations culture T1 predictor User satisfaction accuracy User satisfaction content b b User satisfaction user friendliness User satisfaction format System usage Readiness for change

b Step 1 Human relations culture R2 Step 2 Readiness for change R2ch.

-0.01

-0.13

-0.08 -0.14 -0.06 -0.20

-0.09

-0.24

0.26* 0.13

0.33**

0.04

0.01

0.00

0.01

0.07*

0.11**

0.30* 0.08*

0.16 0.02

0.37** 0.12**

0.38** 0.18**

0.35** 0.10**

Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Analyses Involving Employees Perceptions of a Human Relations Culture Hypothesis 1a states that employees who perceive their division to be high on a culture emphasizing human relations values would report higher levels of user satisfaction and system usage and that this relationship would be mediated by their readiness for change perceptions. To provide evidence of a mediating model, it is necessary to rst establish that the predictor variable (i.e. human relations culture) is signicantly correlated with the outcome variables (i.e. user satisfaction and system usage), thereby establishing if there is a relationship to be mediated. As can be seen in Table II, employees perceptions of a human relations culture were not related to any of the user satisfaction dimensions. There was, however, evidence to suggest that employees perceptions of a human relations culture exerted a positive main effect on system usage, b = 0.26, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.07, F(1, 59) = 4.18, p < 0.05. Next, it needs to be established that the predictor variable is correlated with the mediator (i.e. readiness for change). This step requires that readiness for change be treated as an outcome variable in the analysis. The last column in Table II shows that employees perceptions of a human relations culture were predictive of readiness for change, b = 0.33, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.11, F(1, 60) = 7.43, p < 0.01. The third test requires that readiness for change is correlated with the outcome variable, while controlling for the predictor variable at Step 1. Inspection of Table

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

378

R. A. Jones et al.

II reveals that after the effects of the human relations variable were partialed out readiness for change (entered at Step 2) was predictive of system usage, b = 0.35, p < 0.01, and accounted for a signicant increment of variance, R2ch. = 0.10, F(2, 58) = 8.83, p < 0.01. Fourth, for full mediation to be present, it is necessary to demonstrate that the signicant effect of the human relations culture variable on system usage is no longer signicant when the effects of readiness for change are controlled on the subsequent step. If the strength of this relationship is reduced but remains statistically signicant, then partial mediation is evident. The equation used for the third test is used to establish this effect. Support for Hypothesis 1a was demonstrated in relation to system usage. In this respect, the positive main effect of employees perceptions of a human relations culture on this dependant variable was no longer signicant, once readiness for change was entered into the equation, b = 0.13, NS. Analyses Involving Employees Perceptions of an Open Systems Culture Hypothesis 1b suggested that employees who perceived an open systems culture in their division would have higher levels of user satisfaction and system usage at T2 (compared to employees who rated their organizational culture as being low on this set of values). In addition, this relationship was expected to be mediated by change readiness perceptions. The open systems variable was not signicantly related to any of the user satisfaction indices or employees reports of system usage. Given that the rst condition for mediation was not fullled, subsequent analyses were not necessary. Thus, Hypothesis 1b received no support in the present study. Analyses Involving Reshaping Capabilities The hierarchical multiple regression analyses were continued to test the proposal that reshaping capabilities would lead to high, rather than low, levels of user satisfaction and system usage, via its effects on employees perceptions of readiness for change. First, the extent to which the predictor is correlated with the outcome variables is presented in Table III. As can be seen from this table, employees who perceived their division to have high levels of reshaping capabilities at T1 also reported higher levels of system usage at T2, b = 0.28, p < 0.05, R2 = 0.08, F(1, 63) = 5.98, p < 0.05. Consistent with the previous two sets of analyses, reshaping capabilities was not predictive of user satisfaction. Second, reshaping capabilities exerted a positive main effect on readiness for change, b = 0.33, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.11, F(1, 64) = 7.92, p < 0.01. Third, readiness for change (entered at Step 2) was predictive of system usage, b = 0.38, p < 0.01, R2ch. = 0.14, F(2, 62) = 11.42, p < 0.01, once the effects of the reshaping capabilities were taken into account at Step 1. The positive main effect of reshaping capabilities on system usage was no

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

Table III. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses involving reshaping capabilities T1 predictor User satisfaction accuracy User satisfaction content b b User satisfaction user friendliness b b User satisfaction format System usage

379

Readiness for change

b Step 1 Reshaping capabilities R2 Step 2 Readiness for change R2ch.

-0.01 0.00

-0.10

-0.09 0.01

-0.15

-0.08 0.01

0.03

-0.03 0.00

-0.14

0.28* 0.08*

0.15

0.33** 0.11**

0.29* 0.07*

0.16 0.02

0.32* 0.09*

0.34** 0.10**

0.38** 0.14**

Notes: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

long signicant when readiness for change was added to the equation, b = 0.15, NS. Therefore, the results provided support for a fully mediated relationship between reshaping capabilities and system usage, via employees levels of change readiness. Main Effects of Readiness for Change on User Satisfaction As a consequence of testing for mediation, the main effects of readiness for change perceptions on each of the dependent variables also was examined (see Step 2, Tables II and III). Although there was no support for the mediating role of readiness for change in the prediction of user satisfaction, there was some evidence to suggest that pre-implementation levels of change readiness exerted a direct main effect on the post-implementation measures of accuracy, user friendliness, and formatting characteristics. Thus, employees who felt positive about the impending organizational changes at T1 reported higher levels of satisfaction with the accuracy of the system, the user-friendly nature of the system, and the systems formatting functions after using the new HRIS for a period of one month. It should be noted that regardless of which independent variables were entered at Step 1 (i.e. human relations culture or reshaping capabilities), the effects of readiness for change on these indicators of user satisfaction were relatively consistent. DISCUSSION Some support was found for two of the three hypotheses tested in the present study. In this respect, there was evidence to suggest that employees who perceived strong

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

380

R. A. Jones et al.

human relations values in their division reported higher levels of readiness for change prior to the implementation of the new end-user computing system which, in turn, predicted system usage at T2 (Hypothesis 1a). This nding is consistent with a growing body of research evidence in the area. For instance, Burnes and James (1995) found that change resistance was low when a supportive and participative culture was present, characteristics that are consistent with the human relations culture. Eby et al. (2000) also found that exible policies and procedures, which are artefacts of a human relations culture, were positively related to employees evaluations of whether or not their organization was ready to cope with change events. More recently, Harper and Utley (2001) found that people-orientated values were related to the successful implementation of information technology. The present study supports research of this nature but has demonstrated simultaneously that readiness for change may be the mechanism through which an organizational culture emphasizing human relations values impacts on successful change outcomes. The hypothesized relationship between employees perceptions of an organizational culture strong on open systems values, readiness for change, and change implementation success was not supported (Hypothesis 1b). Although externally focused, the open systems orientation has characteristics similar to the human relations culture type. ONeill and Quinn (1993) note that open systems cultures are characterized by adaptability and a willingness to take on new challenges. Zammuto and Krakower (1991) compliment this argument by commenting that open systems cultures are dynamic and entrepreneurial, usually displaying signicant levels of adaptability and change readiness. The lack of support for Hypothesis 1b might be explained by a study conducted by Cooper (1994) who examined the compatibility of different types of information systems across the four culture types represented in the CVF. He suggested that the implementation of information systems that are incompatible with the cultural values of the organization will result in less than successful change outcomes. Cooper noted that organizations with a strong open systems culture require information systems that focus on the external environment and allow for the scanning and ltering of opportunities that promote linkages across organizations. Organizational systems characterized by informal coordination and reduced control also are key features of this type of organizational culture. These characteristics are somewhat inconsistent with the type of HRIS implemented in the context of this study which was designed to apply structure to internal communication processes. Hence, employees with an open systems view of their organizational culture may have felt that the new computing system was incompatible with the way in which work was done in their division, thereby reducing the role that these cultural values had on change readiness and the outcome variables of user satisfaction and system usage. The hypothesis that reshaping capabilities would be positively related to system usage via readiness for change was supported (Hypothesis 2). Turner and Craw Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

381

ford (1998) believe that if an organization has strong reshaping capabilities, many actions that help to achieve organizational change will take place as part of the normal way in which the workplace functions. As noted earlier, reshaping capabilities focus on engagement, development, and performance management. These reshaping capabilities are consistent with strategies discussed in the readiness for change literature for creating and maintaining a sense of employee readiness for change. Although a measure was developed for use in the present study that incorporated these three dimensions, it was treated as a uni-dimensional scale in the analyses. A useful direction for future research would be to develop more comprehensive measures for each dimension in order to more fully understand which type of reshaping capabilities are more or less important in promoting readiness for change and change implementation success. The extent to which different reshaping capabilities are required for organizational changes of a technological nature also requires further empirical investigation. It also should be noted that there are similarities between the values inherent in a human relations culture and the notion of reshaping capabilities. Characteristics of the human relations culture are generally consistent with engagement, development, and performance management capabilities. Indeed, Turner and Crawford (1998) also have recognized this link, stating that an organization with a human relations culture will have in place practices that facilitate individual and collective behaviour towards better change outcomes Although the two variables were empirically related, r = 0.30, p < 0.05, this correlation is not high enough to suggest that they are one in the same. Nevertheless, future studies should investigate more closely the link between different types of organizational culture and the existence of reshaping capabilities. Another avenue for future research in this area concerns the notion of readiness for change and the extent to which it should be treated as a multifaceted construct, both conceptually and empirically. Although the seven-item scale used in the present study was adapted from previous scales (e.g. Miller et al., 1994), it is acknowledged that these items focused mostly on whether or not employees felt that the new HRIS would be personally benecially to them and the way they performed their job. This approach did not fully capture existing denitions of readiness for change that refer to levels of change acceptance, as well as whether or not employees expect there to be positive implications for not just themselves, but the wider organization (Armenakis et al., 1993). The limited operationalization of this variable should be improved upon in future research. Indeed, Holt (2002) has recently begun work on a multifaceted measure of readiness for change that distinguishes between ve different components of change readiness. These include the extent to which employees perceive a legitimate need for the proposed change, view the change as personally benecial, believe that the change is of benet to the organization, feel that they can cope with the change (i.e. self-efcacy), and lastly, whether or not management have demonstrated support for the change. It

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

382

R. A. Jones et al.

is likely that future research examining the antecedents and consequences of readiness for change will benet from more precise measurement of this construct. This study presents some encouraging results of importance to the organizational change literature. However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to several issues. In particular, the small sample size is a potential threat to the stability of the analyses. In this respect, 67 cases is unlikely to have provided the statistical power needed to detect the full extent of the complex relationships proposed in the present study. Furthermore, there is a risk that the two signicant ndings detected in this study (in relation to system usage) may simply be a consequence of chance. In this respect, it should be noted that each of the three hypotheses were examined in multiple independent tests (one for each of the ve dependent variables) which may have increased the risk of Type 1 error (see Cohen and Cohen, 1983). Indeed, support for only two of the 15 tests for mediation performed on the data highlights the limited ndings of the study. In addition, the small sample size has the potential to jeopardize the generalizability of the results to the rest of the population. Although it was statistically shown that those who failed to respond at T2 were not signicantly different on the focal variables from those who responded at both points in time, it is important to consider those employees who did not respond at all. In this respect, it was possible to determine that the T1 sample was relatively comparable in terms of gender and organizational unit to the wider pilot group, but there may be other unknown variables on which these two groups differed. Generalizability is further diminished as the results were derived from an investigation of employees in a single organization, more importantly, a public sector organization. This had the effect of limiting the variance in culture types, with the majority of employees reporting that their division was most like the internal process culture (see also Parker and Bradley, 2000, for similar ndings). Another limitation of the present study concerns the fact that only ve weeks lapsed between the collection of the T1 and T2 data. This was a relatively short period of time and may only have captured employees initial impressions about the new information system. Baronas and Louis (1988) utilized a longitudinal design in their study of user involvement and system acceptance and measured post-implementation satisfaction eight weeks after implementation. Further, Vankatesh and Davis (2000) in their study on the technology acceptance model, measured usage at four points in time, ranging from one month to ve months after implementation. It would be valuable, in future research, to measure user satisfaction and system usage again, perhaps six months after the implementation, so that the long-term effects of organizational culture and reshaping capabilities on satisfaction and usage can be identied. However, it is important to note that a balance needs to be obtained, as researchers have highlighted that greater experience with the computing system tends to decrease the strength of implementation success perceptions (Vankatesh and Davis, 2000). Indeed, Pare and Elam (1995)

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

383

also have noted that factors such as cultural norms tend to become less salient over time in the use of information systems. To conclude, this research was aimed at identifying the predictors and outcomes of readiness for change, in the context of an information system implementation. In the present study, there was evidence to suggest that readiness for change acted as a mediator in the relationship between employees perceptions of a human relations culture orientation and their subsequent usage of the new computing system. A similar pattern of results was found in relation to reshaping capabilities. In addition, T1 perceptions of readiness for change were a strong predictor of user satisfaction at T2. These results reinforce the importance of undertaking preimplementation assessments of readiness for change. Such assessments should help change agents to make specic choices about strategies and tactics that are needed to help foster employee enthusiasm for specic change events. Overall, results from the present study highlight the importance of assessing the determinants of readiness for change as premature implementation may not produce intended outcomes simply because employees are not psychologically ready.

REFERENCES

Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G. and Mossholder, K. W. (1993). Creating readiness for change. Human Relations, 46, 681703. Armenakis, A. A., Harris, S. G. and Feild, H. S. (1999). Making change permanent: a model for institutionalizing change interventions. In Pasmore, W. A. and Woodman, R. W. (Eds), Research in Organizational Development and Change. Stamford, CT: JAI Press, 97128. Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99120. Baron, R. and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 117382. Baronas, A. and Louis, M. (1988). Restoring a sense of control during implementation: how user involvement leads to system acceptance. MIS Quarterly, 12, 11123. Beckard, R. and Harris, R. (1987). Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Change. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Bjorn-Anderson, N. (1988). Are human factors human?. The Computer Journal, 31, 38690. Bradley, L. and Parker, R. (2001). Public sector change in Australia: are managers ideals being realized?. Public Personnel Management, 30, 34961. Buenger, V., Daft, R. L., Conlon, E. J. and Austin, J. (1996). Competing values in organizations: contextual inuences and structural consequences. Organization Science, 7, 55776. Burnes, B. and James, H. (1995). Culture, cognitive dissonance, and the management of change. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 15, 1433. Cameron, K. S. and Freeman, S. J. (1991). Cultural congruence, strength, and type: relationships to effectiveness. In Woodman, R. W. and Passmore, W. A. (Eds), Research in Organization Change and Development. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 2358. Cavana, R., Delahaye, B. and Sekaran, U. (2000). Applied Business Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Singapore: Wiley. Cohen, J. and Cohen, P. (1983). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Cooper, R. (1994). The inertial impact of culture on IT implementation. Information Management, 27, 1731. Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefcient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297334.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

384

R. A. Jones et al.

Cummings, T. G. and Worley, C. (2001). Organization Development and Change. Cincinnati, OH: SouthWestern Publishing. DeLone, W. and McLean, R. (1992). Information system success: the quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3, 6095. Detert, J., Schroeder, R. and Maurial, J. (2000). A framework for linking culture and improvement initiatives in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 25, 85063. Doll, W. and Torkzadeh, G. (1988). The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Quarterly, 12, 25974. Eby, L. T., Adams, D. M., Russell, J. E. A. and Gaby, S. H. (2000). Perceptions of organizational readiness for change: factors related to employees reactions to the implementation of teambased selling. Human Relations, 53, 41942. Etezadi-Amoli, J. and Farhoomand, A. (1991). On end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Quarterly, 15, 4. Fuerst, W. and Cheney, P. (1982). Factors affecting the perceived utilization of computer-based decision support systems. Decision Sciences, 13, 55469. Gifford, B. D., Zammuto, R. F. and Goodman, E. A. (2002). The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses quality of work life. Journal of Healthcare Management, 47, 1325. Grant, R. (1998). Contemporary Strategy Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell. Guimaraes, T., Igbaria, M. and Ming-Te, L. (1992). The determinants of DSS success: an integrated model. Decision Sciences, 23, 40930. Gutek, B. and Bikson, T. (1985). Differential experiences of men and women in computerized ofces. Sex Roles, 13, 12336. Haines, V. and Petit, A. (1997). Conditions for successful human resource information systems. Human Resource Management, 36, 26175. Harper, G. and Utley, D. (2001). Organizational culture and successful information technology implementation. Engineering Management Journal, 13, 1116. Hicks, L. E. (1970). Some properties of ipsative, normative, and forced-choice normative measures. Psychological Bulletin, 74, 16784. Hirscheim, R. and Newman, M. (1988). Information systems and user resistance: theory and practice. The Computer Journal, 31, 398408. Holt, D. T. (2002). Readiness for Change: The Development of a Scale. 62nd Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Denver, United States of America, 914 August. Howard, G. (1986). Computer Anxiety and the Use of Microcomputers in Management. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press. Howard, L. W. (1998). Validating the competing values model as a representation of organizational cultures. The International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 6, 23150. Ives, B., Olson, M. and Baroudi, J. (1983). The measurement of user information satisfaction. Communications of the ACM, 26, 78593. James, L. R. and Brett, J. M. (1984). Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 30721. Kalliath, T. J., Bluedorn, A. C. and Gillespie, D. F. (1999). A conrmatory factor analysis of the competing values instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 14358. Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. and Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In Gilbert, D. Fiske, S. and Lindzey, G. (Eds), The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 23365. Lee, S., Kim, Y. and Lee, J. (1995). An empirical study of the relationships among end-user information systems acceptance, training, and effectiveness. Journal of Management Information Systems, 12, 189201. Lucas, H. J. (1973). A descriptive model of information systems in the context of the organization. Data Base, Winter, 2736. Lucas, H. J. (1975). Performance and the use of an information system. Management Science, 21, 90819. Martinko, M., Henry, J. and Zmud, R. (1996). An attributional explanation of individual resistance to the introduction of information technologies in the workplace. Behavior and Information Technology, 15, 31330. Meyer, M. and Utterback, J. (1993). The product family and the dynamics of core capability. Sloan Management Review, Spring, 2947.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

Culture, Capabilities and Readiness for Change

385

Miller, D. and Chen, M. (1994). Sources and consequences of competitive inertia. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 115. Miller, V. D., Johnson, J. R. and Grau, J. (1994). Antecedents to willingness to participate in a planned organizational change. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 22, 5980. Mulaik, S. (1972). The Foundations of Factor Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. Ogbonna, E. and Wilkinson, B. (2003). The false promise of organizational culture change: A case study of middle managers in grocery retailing. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 5, 115178. ONeill, R. and Quinn, R. (1993). Editors note: Applications of the competing values framework. Human Resource Management, 32, 17. Ott, J. S. (1989). The Organizational Culture Perspective. Chicago, IL: Dorsey Press. Pare, G. and Elam, J. (1995). Discretionary use of personal computers by knowledge workers: testing of a social psychological theoretical model. Behaviour and Information Technology, 14, 21528. Parker, R. and Bradley, L. (2000). Organizational culture in the public sector: evidence from six organizations. The International Journal of Public Sector Management, 13, 12441. Paton, R. and McCalman, J. (2000). Change Management: A Guide to Effective Implementation. London: Sage. Penrose, E. (1959). The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. London: Basil Blackwell. Pfeffer, J. (1982). Organizations and Organization Theory. Cambridge, MA: Pitman. Pinto, J. (1994). Successful Information System Implementation: The Human Side. Upper Darby: Project Management Institute. Podsakoff, P. M. and Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12, 53144. Quinn, R. E. (1988). Beyond Rational Management. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Quinn, R. E. and Cameron, K. S. (1983). Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: some preliminary evidence. Management Science, 29, 3352. Quinn, R. E. and Hall, R. H. (1983). Environments, organizations, and policymakers: toward an integrative framework. In Hall, R. H. and Quinn, R. E. (Eds), Organizational Theory and Public Policy. Beverly Hill, CA: Sage, 28198. Quinn, R. E. and Kimberly, J. R. (1984). Paradox, planning, and perseverance: guidelines for managerial practice. In Kimberly, J. R. and Quinn, R. E. (Eds), Managing Organizational Translations, Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin, 296313. Quinn, R. E. and Rohrbaugh, J. (1981). A competing values approach to organizational effectiveness. Public Productivity Review, 5, 12240. Quinn, R. E. and Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: toward a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29, 36377. Quinn, R. E., Hildebrandt, H. W., Rogers, P. S. and Thompson, M. P. (1991). A competing values framework for analyzing presentational communications in management context. Journal of Business Communications, 28, 21332. Raymond, L. (1985). Organizational characteristics and MIS success in the context of small business. MIS Quarterly, 9, 3752. Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human Values. New York: The Free Press. Santhanam, R., Guimaraes, T. and George, J. (2000). An empirical investigation of ODSS impact on individuals and organizations. Decision Support Systems, 30, 5172. Schein, E. H. (1987). Process Consultation: Lessons for Managers and Consultants. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. Schein, E. H. (1988). Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley. Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45, 10919. Schein, E. H. (1999). Process Consultation Revisited: Building the Helping Relationship. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Sharma, S. and Vredenburg, H. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 72953. Shortell, S. M., OBrien, J. L., Carman, J. M., et al. (1995). Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement/total quality management: concept versus implementation. Health Services Research, 30, 377401. Tabachnick, B. and Fidell, L. (2001). Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: Harper Collins.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

386

R. A. Jones et al.

Teece, D. (1982). Towards an economic theory of the multi-product rm. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 3, 3963. Teece, D. and Pisano, G. (1994). The dynamic capabilities of rms: an introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3, 53756. Teece, D., Pisano, G. and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 50933. Turner, D. and Crawford, M. (1998). Change Power: Capabilities that Drive Corporate Renewal. Warriewood, NSW: Business and Professional Publishing. Vankatesh, V. and Davis, F. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal eld studies. Management Science, 46, 186204. Waldersee, R., Grifths, A. and Lai, J. (2003). Predicting organizational change success: matching organization type, change type, and capabilities. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 8, 6681. Wanberg, C. R. and Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 13242. Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the rm. Strategic Management Journal, 5, 17180. Zammuto, R. F. and Krakower, J. (1991). Quantitative and qualitative studies of organizational culture. In Woodman, R. W. and Passmore, W. A. (Eds), Research in Organizational Change and Development. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 83144. Zammuto, R. F. and OConnor, E. (1992). Gaining advanced manufacturing technologies benets: the roles of organization design and culture. Academy of Management Review, 17, 70128. Zammuto, R. F., Gifford, B. D. and Goodman, E. A. (2000). Managerial ideologies, organization culture, and outcomes of innovation: a competing values perspective. In Ashkanasy, N. M., Wilderom, C. and Peterson, M. F. (Eds), The Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 26178. Zapf, D., Dormann, C. and Frese, M. (1996). Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: a review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 14569. Zoltan, E. and Chapanis, A. (1982). What do professional persons think about computers?. Behavior and Information Technology, 1, 5568.

Blackwell Publishing Ltd 2005

You might also like

- Employee Readiness To Change and Individual IntelligenceDocument9 pagesEmployee Readiness To Change and Individual IntelligenceWessam HashemNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Organizational Readiness For ChangeDocument9 pagesA Theory of Organizational Readiness For ChangeHasimi AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Cultural Web NHS StrategyDocument4 pagesCultural Web NHS StrategyÄßħīłăşħ ĹăĐĐüNo ratings yet

- Snippets On Change ManagementDocument32 pagesSnippets On Change Managementzahirzaki100% (1)

- Organizational Structure ALLDocument25 pagesOrganizational Structure ALLMinhaz ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- ADB-SC Professional Public ProcurementDocument37 pagesADB-SC Professional Public ProcurementButch D. de la CruzNo ratings yet

- A Study On New Prospect Identification in Emerging MarketsDocument65 pagesA Study On New Prospect Identification in Emerging MarketsrohanjavagalNo ratings yet

- The Cultural Web: Mapping and Re-Mapping Organisational Culture: A Local Government ExampleDocument12 pagesThe Cultural Web: Mapping and Re-Mapping Organisational Culture: A Local Government ExampleQuang Truong100% (1)

- Chapter 9 - Organization LearningDocument19 pagesChapter 9 - Organization LearningProduk KesihatanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management in The Public SectorDocument3 pagesStrategic Management in The Public SectorSepti SetiartiNo ratings yet

- PoM Organizational ObjectivesDocument8 pagesPoM Organizational ObjectivesKipasa ArrowNo ratings yet