Professional Documents

Culture Documents

13 Purpose and Problems of Periodontal Disease Classification

Uploaded by

Emine AlaaddinogluCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13 Purpose and Problems of Periodontal Disease Classification

Uploaded by

Emine AlaaddinogluCopyright:

Available Formats

Periodontology 2000, Vol. 39, 2005, 1321 Printed in the UK.

All rights reserved

Copyright Blackwell Munksgaard 2005

PERIODONTOLOGY 2000

Purpose and problems of periodontal disease classication

UBELE

VAN DER

VELDEN

There has been a debate on the diagnosis and classication of periodontal diseases since dentists rst became interested in periodontology. In this respect, periodontology is not unique; comparable discussions can be encountered in many elds of medicine, especially in complex diseases. Diagnosis is dened as the act of identifying a disease from its signs and symptoms, whereas classication is dened as the act or method of distribution into groups. The present article deals with the periodontal condition which is clinically characterized by three symptoms: loss of connective tissue attachment, loss of alveolar bone support, and inamed pathological pockets. On the basis of these three symptoms one diagnostic name for this condition would be appropriate, e.g. destructive periodontal disease. However, if age, distribution of lesions, degree of gingival inammation, putative rate of breakdown, response to therapy, etc., are also taken into account, numerous diagnostic names are needed. In order to be able to communicate about patients, clinicians have always felt the need for diagnostic names and classications for these diseases, preferably on the basis of putative etiologic factors. At present, controversies about denitions of diseases continues, not only in the periodontal eld but also in medicine. An interesting contribution to the discussion on disease terminology is a paper by Scadding (31) entitled: Essentialism and nominalism in medicine: logic of diagnosis in disease terminology. In this paper the clear distinction between these two types of denitions is highlighted. The essentialistic idea implies the real existence of a disease. Essentialist denitions typically start X is , implying a priori the existence of something that can be identied as X. Thus the doctors skills consist in identifying the causal disease and then prescribing the appropriate treatment. In relation to this, Scadding states:

The essentialists hankering after a unied concept of diseases as a class of agents causing illness, is mistaken and misleading for several good reasons: many diseases remain of unknown cause; known causes are of diverse types; causation may be complex, with interplay of several factors, intrinsic; and, more generally, an effect the disease should not be confused with its own cause. The counterpart of essentialism is nominalism, which implies that a disease name is just a name given to a group of subjects who share a group of welldened signs and symptoms. Scadding supports the nominalistic concept and states: The names of diseases are a convenient way of stating briey the endpoint of a diagnostic process that progresses from assessment of symptoms and signs towards knowledge of causation. Ideally, a nominalistic disease denition describes a set of criteria that are fullled by all persons said to have the disease, but not fullled by persons that are considered free from the disease (40). This set of criteria is dependent on the level of knowledge of a given disease. For example, if the etiology is known, e.g. cholera, then the key criterion for the disease is the presence of Vibrio cholerae. However, for many diseases the etiology is complex or not known, and consequently a large number of diseases are dened as syndromes. A syndrome constitutes a distinct group of symptoms and signs which together form a characteristic clinical picture or entity. In this respect periodontitis is a good example of a syndromically dened disease (10, 36).

Need for classication

Syndromic classication(s) are needed to cluster similar disease phenotypes in more homogeneous

13

van der Velden

syndromes. This is the prerequisite to establish etiology and susceptibility traits, and thus separate truly different forms of disease or conversely link different different phenotypic variations to the same underlying disease (35). As mentioned above, the names of a disease are a convenient way of stating briey the endpoint of a diagnostic process that progresses from the assessment of symptoms and signs towards knowledge of causation (31). In other words, in order to obtain more knowledge about the causation of periodontal diseases the various forms of the disease have to be classied. The term periodontal disease has referred for some time to all diseases which affect one or more tissues from the periodontium (2). However, in 1964 Sherp (32) noted: Discussions of periodontal disease commonly begin with the tacit assumption that all participants are considering the same entity. Since the variations of periodontal diseases are almost limitless, depending on ones taste for subclassication, this unqualied usage often leads to fruitless semantic misunderstandings. What is usually meant is the most common form of periodontal disease a chronic, slowly progressive and destructive inammatory process affecting one or more of the supporting tissues of the teeth the gingival tissue, the periodontal membrane, and the alveolar bone. This statement, made 40 years ago, is still valid today; it also highlights one of the most frequent premises in periodontal diagnosis: the assumptions concerning previous disease progression. In this respect, age has always been an important parameter in periodontal diagnosis.

Previous classications

Almost all ancient medical works refer to the various diseases of the teeth and their supporting tissues but without using any particular terminology. The rst specic name for periodontal disease was introduced by Fauchard in 1723 using the term scurvy of the gums (15). Ever since, researchers have introduced names for diseases of the periodontium on the basis of etiologic factors, pathologic changes or clinical manifestations. Gottlieb is generally considered to be the rst author who clearly distinguished various forms of periodontal disease. In the 1920s he classied perio-

dontal disease into four types (1618): Schmutz e, alveolar atrophy or diffuse atrophy, Pyorrho e, and occlusal trauma. SchmutzParadental-Pyorrho e was thought to be the result of the Pyorrho accumulation of deposits on the teeth and was characterized by inammation, shallow pockets, and resorption of the alveolar crest. Alveolar atrophy or diffuse atrophy was described as a noninammatory disease exhibiting loosening of teeth, elongation, and wandering of teeth in individuals who were generally free of carious lesions and dental deposits. In this disease, manifesting pockets are formed only in later e was characterized by stages. Paradental-Pyorrho irregularly distributed pockets varying from shallow to extremely deep. This form of disease may have e or as diffuse atrophy. started as Schmutz-Pyorrho The fourth type was occlusal trauma, a form of physical overload which was believed to result in resorption of the alveolar bone and loosening of teeth. More or less at the same time, McCall & Box (24) introduced the term periodontitis to denote those inammatory diseases in which all three components of the periodontium, i.e. the gingiva, bone, and periodontal ligament, were affected. This is in contrast to the lesions of occlusal traumatism and atrophic lesions, in which only the bone and periodontal ligament may be involved. Periodontitis was subclassied, on the basis of presumed etiologic factors, into Simplex periodontitis, considered to be the result from local bacterial factors, and Complex periodontitis, a result of systemic etiologic factors. Becks (11) made a distinction between paradentitis, a disease which originates from the gum tissue in the form of gingivitis and genuine paradentosis, which originates in the bony alveolus, perhaps in the form of an osteopathy. Orban & Weinmann (25) adopted this nomenclature using the anglicized term periodontosis to designate this noninammatory disease. Periodontosis was considered a separate disease entity, distinctly different from periodontitis, which was considered the sequela of gingivitis of the deeper periodontal structures, and therefore of inammatory origin. It is remarkable that in relation to the issue of degenerative disease it is not mentioned specically that this was a disease entity particular to young subjects (23). During the 1950s and 1960s the importance of dental plaque as the major etiologic factor for periodontal diseases became more and more evident. The ultimate proof of the association between plaque and gingival inammation was shown by e and coworkers in their experimental gingivitis Lo

14

Periodontal disease classication

studies (22, 34). The inuence of this way of thinking was clearly evident during the 1966 Workshop in Periodontics when the entity periodontosis was revisited (13). In the committee report it was concluded: Evidence to support the conventional concept of periodontosis is unsubstantiated. It was the consensus of the section that the term periodontosis is ambiguous and that the term should be eliminated from periodontal nomenclature. Nevertheless, the committee is aware that some evidence exists to indicate that a clinical entity different from adult periodontitis may occur in adolescents and young adults. Therefore it is not surprising that soon after the Workshop a study was published by Butler (12) introducing the name juvenile periodontitis instead of periodontosis when describing the periodontal condition of young individuals with severe periodontal bone loss. According to Butler there was no proof of any degenerative process, as the sufx osis would imply. Numerous classications have since been published. Page & Schroeder (28) dened periodontitis as an inammatory disease of the periodontium characterized by the presence of periodontal pocket(s) and active bone resorption with acute inammation. They suggested at least four distinctly different forms of periodontitis in humans: prepubertal, juvenile, rapidly progressive, adult periodontitis, and acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivo-periodontitis (ANUG P). In this classication, with the exception of ANUG P, the age of onset is of decisive importance. This item is adopted in almost all subsequent classications. In 1986 the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) adopted the following classication (3): I Juvenile periodontits A Prepubertal periodontitis B Localized juvenile periodontitis C Generalized juvenile periodontitis II Adult periodontis III Necrotizing ulcerative gingivo-periodontitis IV Refractory periodontitis. In an attempt to detect groups and individuals at high risk for periodontal disease, Johnson et al. (20) presented a more extensive classication: I Childhood periodontitis including specic syn` fre dromes such as Papillon-Leve II Juvenile periodontitis: localized; generalized III Post-juvenile periodontitis

IV Adult onset periodontitis: slowly progressive; rapidly progressive V Periodontitis associated with systemic diseases such as diabetes, scurvy, immunodeciencies (including AIDS), immunosuppressive states, blood dyscrasias VI Traumatic periodontitis, e.g. gingival recession and loss of attachment as a result of abrasion during oral hygiene practice (toothbrushing, wood sticks, charcoal, brick dust; trauma from occlusion) VII Iatrogenic periodontitis, due to inappropriate restorations or inappropriate instrumentation of the gingival crevice. At the same time a new classication was proposed by Suzuki (33). Suzuki stated that Additional clinical observations in our laboratories during investigation on the mode of inheritance of juvenile and rapidly progressive periodontitis have suggested that further qualications can be made. Based on factors such as age, microbial deposits, and the autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction, rapidly progressive periodontitis, as introduced by Page & Schroeder (28), can be subdivided into type A and type B. In addition, the term postjuvenile periodontitis delineated a slowprogression-type of juvenile periodontitis. One year later it was stated in the 1989 World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics that although the AAP classication was adopted, legitimizing the idea that different forms of periodontal diseases exist, more recently acquired data mandate modication and revision (4). The following classication was recommended: I Adult periodontitis II Early onset periodontitis A Prepubertal periodontits 1 Generalized 2 Localized B Juvenile periodontitis 1 Generalized 2 Localized C Rapidly progressive periodontitis III Periodontitis associated with systemic diseases IV Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis V Refractory periodontitis. Volume 2 of Periodontology 2000, issued in 1993, was dedicated to the classication and epidemiology of periodontal diseases. In the contribution of Ranney (30) four major disease categories were proposed, i.e. adult periodontitis, early onset periodontitis, necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis, and periodontal abscess including a large number of subcategories mainly based on systemic factors. Also in 1993, the

15

van der Velden

rst European Workshop on Periodontology was organized. In session I the following position papers were presented. Papapanou: epidemiology and natural history of periodontal disease (29), Claffey: Gold Standard Clinical and radiographical assessment of disease activity (14), Tonetti: Etiology and pathogenesis (35) and Johnson: Risk factors and diagnostic tests for destructive periodontitis (19). On the basis of these comprehensive reviews a consensus report was produced (9) that included the following statement regarding the classication of periodontal diseases: There is insufcient knowledge to separate truly different diseases (disease heterogeneity) from differences in the presentation severity of the same disease (phenotypic variation). Because of this, existing classications are unsatisfactory. Disadvantages of present classications (e.g. AAP 1989) include 1. extensive overlap between the different diagnostic categories, 2. need for assumptions concerning previous disease progression, 3. the necessity for detailed information on the quality of treatment provided previously and the patient response to this therapy, and 4. the apparent lack of a consistent basis for classication. Ideally classications should be based on etiologic and host response factors. In order to deal with the present confusion, a simple classication distinguishing between 1. Early onset periodontitis, 2. Adult periodontitis, 3. Necrotizing periodontitis, might be preferable. Provided that the relevant information is available, as many as possible additional secondary descriptors should be used to further dene the clinical situation. These include distribution within the dentition, rate of progression, response to treatment, relation to systemic diseases, microbiological characteristics, ethnic group and other factors. Although, in my opinion, the conclusion there is insufcient knowledge to separate truly different diseases (disease heterogeneity) from differences in the presentation severity of the same disease (phenotypic variation) from the European Workshop on Periodontology in 1993 (9) still holds true today, it was concluded in the 1996 World Workshop in Periodontics that there was a clear need for a revised classication system for periodontal diseases (5). This resulted in a new classication which was agreed upon at the International Workshop for a Classication of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions in 1999 (6). This classication included many disease categ-

ories and subcategories and was certainly an improvement with regard to the category gingival diseases. However, a number of subcategories present in the majority of the previous classications were eliminated, i.e. prepubertal periodontitis, juvenile periodontis, postjuvenile periodontitis, rapidly progressive periodontitis, early onset periodontitis and refractory periodontitis. Amongst others it was argued that: in case of early onset periodontitis (prepubertal periodontitis, juvenile periodontitis, postjuvenile periodontitis and rapidly progressive periodontitis), one must have temporal knowledge of when the disease started. In addition, there is considerable uncertainty about arbitrarily setting an upper age limit for patients with so-called early onset periodontitis. For example, how does one classify the type of periodontal disease in a 21-year old patient with the classical incisor-rst molar pattern of Localized Juvenile Periodontitis (LJP)? Since the patient is not a juvenile, should the age of the patient be ignored and the disease classied as LJP anyway? On the basis of this and other arguments the workshop participants decided that it was wise to discard classication terminologies that were agedependent or required knowledge of rates of progression (6). Therefore it was proposed to re-name the disease formerly considered under the umbrella early onset periodontitis and other forms of rapidly progressive disease by aggressive periodontitis. Although not clearly stated, it can be concluded from the report that the term aggressive periodontitis is only applicable for patients with severe periodontal breakdown. However, it can be argued that this new classication does not solve the problems because it is not clear how severe a case must be in order to be classied as aggressive periodontitis, and knowledge about the rate of progression is still needed. In the same Workshop, adult periodontitis was renamed chronic periodontitis on the basis of the assumption that slowly progressive disease can be present at any age, i.e. in adults as well as in adolescents. But again it can be argued that for this classication, knowledge about the rate of progression is still needed. The problems related to the prediction of the rate of progression in the future or assumptions on the rate of progression in the past are clearly illustrated by the study of Albandar et al. (1). In this longitudinal study, young individuals, mean age at baseline

16

Periodontal disease classication

Fig. 2. Bitewing radiographs from the same patient as in Fig. 1 when he was 45 years old.

Fig. 1. Radiographs of a 50-year-old male patient when he was referred to the Department of Periodontology at ACTA. Fig. 3. Bitewing radiographs from the same patient as in Fig. 1 when he was 49 years old.

16 years, were reexamined 6 years later. On the basis of the baseline measurements the individuals were classied into localized juvenile periodontitis, generalized juvenile periodontitis, incidental attachment loss, and no-periodontitis group. The results showed low correlations between baseline disease classications and the classications at the 6-year follow-up examination. In addition, the cross-sectional classications were not predictive of the rate of progression of periodontal disease in these subjects. Sometimes retrospective documentation of cases gives interesting information. Figure 1 shows radiographs of a 50-year-old patient when he was referred to the Department of Periodontology at ACTA. Bitewing radiographs could be retrieved from his dentist when the patient was 45 (Fig. 2) and 49 years old (Fig. 3). It was obvious that most of the breakdown had occurred in 1 year. The medical history revealed no particular problems. This case clearly illustrates that without documentation, assumptions on the rate of previous disease progression are made blindly, although in general, periodontitis is a slowly pro-

gressive disease whose pace may vary between individuals as well as during life. In a review on classication of periodontal diseases in 2002, Armitage (7) stated that if a classication is based on the extent and severity of the disease, age, and rate of progression, this would represent a return to the domination of the Clinical Characteristics paradigm that reigned from approximately 1870 to 1920, when we knew little about the nature of periodontal diseases. The 1999 classication is based on the Infection Host Response paradigm that started to be the dominant paradigm in the 1970s. According to Armitage, the 1999 classication is even more rmly based on the Infection Host Response paradigm. However, it can be argued that, at present, regardless of the enormous increase in knowledge of periodontal diseases, we still know too little to diagnose and classify the periodontal disease of a patient on an etiologic basis.

17

van der Velden

Essentialistic or nominalistic disease classication

As Sherp (32) noted in 1964: Discussions of periodontal disease commonly begin with the tacit assumption that all participants are considering the same entity. In order to be able to discuss cases between colleagues it is for clinicians of paramount importance to be able to give a diagnostic name to a patient with periodontitis. One obvious problem is that one of the most important components of periodontitis is expressed in all patients in the same way, i.e. the amount of loss of attachment. This can be illustrated by the example that 2 mm loss of attachment mesial of all rst molars in an 8-year child is a severe problem suggestive for an individual that is highly susceptible to periodontal disease, whereas the same condition in a 60 years old subject may suggest that the individual is rather resistant to periodontal disease. Figure 4 illustrates this problem. The essentialistic idea implies the real existence of a disease caused by a class of agents. However, to date, all indications have been that the causal web for periodontitis is so complex and involves so many factors in so many different constellations that a classication of periodontitis based on etiology is effectively precluded (10). Since periodontitis has to be regarded as a syndrome, present and future classications of periodontitis have to be based on the nominalistic concept. Classications based on this concept should be simple to apply and not susceptible to multiple interpretations. Ideally, such a classication should

be determined on the basis of documented differences regarding the consequences of the diagnosis (10). Unfortunately, to date there is insufcient knowledge to make a classication based on this principle. However, it is most convenient if the terminology used describes the patient in such a way that all clinicians immediately have a clear image of a case. The recent classication into aggressive and chronic periodontitis (6) does not fulll this criterion since the criteria are too indenite. However, in a recent review Armitage (8) again discussed periodontal diagnoses and classication. In this review he accepted, in a way, the nominalistic concept by stating that a diagnosis can be phrased many different ways depending on how precise or detailed one wants to be. With regard to the distinction between aggressive and chronic periodontitis it can be argued that all forms of periodontitis are chronic in nature, with the exception of acute necrotizing periodontitis and a periodontal abscess. This would imply that there is no place for the diagnosis aggressive periodontitis, leaving the diagnosis chronic periodontitis for all cases of periodontitis, a situation which is not feasible in practice. Especially in relation to research into the etiology of the various manifestations of periodontitis, it is of utmost importance to include clear phenotypes in the study groups. For clinicians the most important characteristic of a patient is the extent and severity of the periodontal destruction in relation to age.

Classication according to the nominalistic concept

At present, the best option is to classify the periodontitis syndrome in an exhaustive but also exclusive way and use a terminology for the various classes of

Severity of the periodontal problem

Severe

Moderate

PD 4 mm + AL 1 mm PD 4 mm + AL 2 mm PD 4 mm + AL 4 mm

Minor

10

20

30

40

50

60

Age

Fig. 4. Estimation of the severity of the periodontal problem in relation to age. PD pocket depth. AL attachment level.

18

Periodontal disease classication

Table 1. Classication based on the extent of the disease. If teeth are missing, the class description should still reect the clinical image of the patient. Therefore it was decided for cases with 14 teeth to omit the class semigeneralized and to change the number of teeth for the generalized class to 814

Permanent mixed dentition No. of teeth present n 14 Incidental Localized Semi-generalized Generalized 1 tooth 27 teeth 813 teeth 14 teeth n 14 1 tooth 27 teeth 814 teeth 1 tooth 24 teeth 59 teeth 10 teeth Primary dentition

the disease which makes it easy to understand the case. A classication which comes closest to these principles was recently published by Van der Velden (38). This classication was based on four dimensions, i.e. extent, severity, age, and clinical characteristics. The following is a presentation of the original classication with a few additions. Dening when periodontitis is considered to be present. It is suggested to dene periodontitis as the presence of inamed pathological pockets 4 mm deep in conjunction with attachment loss. If present, then the next steps can be taken. Classication based on extent of the disease, i.e. number of affected teeth (Table 1). Classication based on severity of disease per tooth (Table 2). The fact that either attachment loss or bone loss can be used for the classication of severity implies that although it may be important to know the actual root length in a given patient, radiographs are not a prerequisite for the classication of severity. Classication based on age (Table 3). Classication based on clinical characteristics (Table 4).

Table 3. Classication based on age. If in patients classied as adult periodontitis it can be demonstrated on the basis of documentation that they already had moderate or severe periodontitis before the age of 36 years, the disease is classied as early onset periodontitis

Early onset periodontitis Prepubertal periodontitis Juvenile periodontitis Postadolescent periodontitis Adult periodontitis 12 years 1320 years 2135 years 36 years

Table 2. Classication based on the severity of disease per tooth. The mean estimated root length based on the literature is approximately 12 mm (21); in the case of incidental disease, the severity category at that particular tooth is mentioned

Minor Moderate Severe bone loss 1 3 of the root length or attachment loss 3 mm bone loss > 1 3 and 1 2 of the root length or attachment loss 45 mm bone loss > 1 2 of the root length or attachment loss 6 mm

The classication is ascertained in the following way: rst, the severity category is determined for each tooth; next, the extent category is determined by counting the number of teeth with the most severe condition; diagnosis on the basis of clinical characteristics is added if applicable; diagnosis on the basis of age. In the nomenclature, the parameters for the classication are set in the following order: extent, severity, clinical characteristics and age. Thus examples for diagnoses are: localized minor prepubertal periodontitis, localized severe juvenile periodontitis, semi-generalized minor juvenile periodontitis, generalized severe refractory post adolescent periodontitis, localized severe adult periodontitis. One could make the diagnosis even more detailed by including two levels of extent and severity when appropriate, e.g. localized severe, semi-generalized moderate adult periodontitis. Traditionally in periodontology, a specic diagnosis has been introduced on the basis of severe cases,

19

van der Velden

Table 4. Classication based on clinical characteristics. Periodontitis associated with systemic diseases, i.e. periodontitis in subjects suffering from general diseases, or periodontitis in subjects using medication, which enhance the rate and severity of periodontal breakdown is not identied as a specic class of periodontitis. However, the association with such a condition should be added to the diagnosis.

Necrotizing periodontitis interdental gingival necrosis, bleeding and pain

tion may help in the search for a better understanding of the disease.

Conclusion

In order to obtain more knowledge about the causation of periodontitis and to be able to discuss cases between colleagues, the various forms of the disease have to be classied. Since periodontitis must be regarded as a syndrome with a complex etiology, classications of periodontitis should be based on the nominalistic concept. Classications based on this concept should be simple to apply and not susceptible to multiple interpretations. In this paper an example of such a classication has been presented.

Rapidly progressive documented rapid breakdown periodontitis (at any age), i.e. rapidly progressive periodontitis patients showing a progression of 1 mm interproximal attachment bone loss per year at affected sites Refractory periodontitis documented, no or minimal pocket depth reduction at single rooted teeth after proper initial therapy and or further attachment loss despite the proper execution of various treatment modalities

References

1. Albandar JM, Brown LJ, Genco RJ, Loe H. Clinical classication of periodontitis in adolescents and young adults. J Periodontol 1997: 68: 545555. 2. American Academy of Periodontology. Report from the 1949 Nomenclature Committee. J Periodontol 1950: 21: 4043. 3. American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of periodontic terms. J Periodontol 1986: Supplement: 13. 4. American Academy of Periodontology. Proceedings of the World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics. Consensus Report, Discussion Section I. Periodontal diagnosis and diagnostic aids. Princeton: American Academy of Periodontology, 1989. 5. Armitage GC. Periodontal diseases: Diagnosis. Ann Periodontol 1996: 1: 37215. 6. Armitage GC. Development of a classication system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 16. 7. Armitage GC. Classifying periodontal diseases a longstanding dilemma. Periodontol 2000 2002: 30: 923. 8. Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classication of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2004: 34: 921. m R, van der Velden U. Consensus session I. In: 9. Attstro Lang, NP, Karring, T, eds. Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Publishing Co., 1994, 120126. 10. Baelum V, Lopez R. Dening and classifying periodontitis: need for a paradigm shift? Eur J Oral Sci 2003: 111: 26. 11. Becks H. What factors determine the early stage of paradentosis (pyorrhea)? J Am Dent Assoc 1931: 18: 922 931. 12. Butler JH. A familial pattern of juvenile periodontitis (periodontosis). J Periodontol 1969: 40: 115118. 13. Carranza F. Periodontal pathology. In: Ramfjord SP, Kerr DA, Ash MM, editors. World Workshop in Periodontics. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 1966: 67126. 14. Claffey N. Gold standard Clinical and radiographical assessment of disease activity. In: Lang NP, Karring T, editors. Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on

e.g. paradontosis (11), juvenile periodontitis (12), rapidly progressive periodontitis (26), and prepubertal periodontitis (27). However, in all patients the disease started initially with minor breakdown and progressed over time. It is only a matter of when the patient is rst diagnosed. For example, in an epidemiologic survey carried out in Amsterdam in 15 16-year-old adolescents (39), 230 out of the 4565 subjects were diagnosed as having periodontitis. These subjects showed a pocket depth 5 mm in conjunction with attachment loss ranging from 1 to 8 mm. However, the majority (74%) had minor loss of attachment ( 3 mm). Therefore it is important that it is possible with a classication system of periodontitis to make a clinical diagnosis for any patient with periodontitis. This will also help in epidemiologic studies to obtain a better insight of the periodontal problem in a given population. In addition, the use of the presented classication based on the nominalistic principle will help the clinician to get a better image of the patient population he is treating. Furthermore, the new classication may help research into the etiology of periodontitis by including the same type of patients in the study protocols. At present, in my opinion response to treatment is still our chief diagnostic method (37). Studying the response to treatment in well described patient populations according to the new classica-

20

Periodontal disease classication

Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Publishing Co., 1994: 120126. Gold SI. Periodontics The past. Part (I) Early sources. J Clin Periodontol 1985: 12: 7997. Gottlieb B. Zur Aetiologie und Therapie der Alveolarporrhoe. Z Stomatol 1920: 18: 5982. Gottlieb B. Die diffuse Atrophie des Alveolar Knochens. Z Stomatol 1923: 31: 195201. Gottlieb B. The formation of the pocket: Diffuse atrophy of alveolar bone. J Am Dent Assoc 1928: 15: 462476. Johnson NW. Risk factors and diagnostic tests for destructive periodontitis. In: Lang NP, Karring T, editors. Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Publishing Co., 1994: 120126. Johnson NW, Grifths GS, Wilton JM, Maiden MF, Curtis MA, Gillett IR, Wilson DT, Sterne JA. Detection of high-risk groups and individuals for periodontal diseases. Evidence for the existence of high-risk groups and individuals and approaches to their detection. J Clin Periodontol 1988: 15: 276282. Klock KS, Gjerdet NR, Haugejorden O. Periodontal attachment loss assessed by linear and area measurements in vitro. J Clin Periodontol 1993: 20: 443447. e H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in Lo man. J Periodontol 1965: 36: 177187. Lopez R. Periodontitis in adolescents. Studies among Chilean high school students. PhD Thesis. Aarhus: University of Aarhus, 2003. McCall JO, Box HK. The pathology and diagnosis of the basic lesions of chronic periodontitis. J Am Dent Assoc 1925: 12: 13001309. Orban B, Weinmann JP. Diffuse atrophy of the alveolar bone (periodontosis). J Periodontol 1942: 13: 3145. Page RC, Altman LC, Ebersole JL, Vandesteen GE, Dahlberg WH, Williams BL, Osterberg SK. Rapidly progressive periodontitis. A distinct clinical condition. J Periodontol 1983: 54: 197209. Page RC, Bowen T, Alyman L, Edward V, Ochs H, Mackenzie P, Osterberg S, Engel LD, Williams BL. Prepubertal periodontitis. I. Denition of a clinical disease entity. J Periodontol 1983: 54: 257271. 28. Page RC, Schroeder HE. Periodontitis in Man and Other Animals. A Comparative Review. Basel: Karger, 1982. 29. Papapanou PN. Epidemiology and natural history of periodontal disease. In: Lang NP, Karring T, editors. Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Publishing Co., 1994: 120126. 30. Ranney RR. Classication of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 1993: 2: 1325. 31. Scadding JG. Essentialism and nominalism in medicine: logic of diagnosis in disease terminology. Lancet 1996: 348: 594596. 32. Sherp HW. Current concepts in periodontal disease research: epidemiological contributions. J Am Dent Assoc 1964: 68: 667675. 33. Suzuki JB. Diagnosis and classication of the periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am 1988: 32: 195216. e H. Experimental 34. Theilade E, Wright WH, Jensen SB, Lo gingivitis in man. II. A longitudinal clinical and bacteriological investigation. J Periodontal Res 1966: 1: 113. 35. Tonetti MS. Etiology and pathogenesis. In: Lang NP, Karring T, editors. Proceedings of the 1st European Workshop on Periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence Publishing Co., 1994: 120126. 36 Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol 1999: 4: 3953. 37. van der Velden U. Response to treatment, our chief diagnostic method? Periodontology Today. International Con rich 1988. Basel: Karger, 1988: 244250. gress, Zu 38. van der Velden U. Diagnosis of periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2000: 27: 960961. 39. van der Velden U, Abbas F, van Steenbergen TJM, De Zoete OJ, Hesse M, De Ruyter C, De Laat VHM, De Graaff J. Prevalence of periodontal breakdown in adolescents and presence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in subjects with attachment loss. J Periodontol 1989: 60: 604610. 40. Wulff HR, Gotzche PC. Rational Diagnosis and Treatment: Evidence Based Clinical Decision Making, 3rd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2000.

15. 16. 17. 18. 19.

20.

21.

22. 23.

24.

25. 26.

27.

21

You might also like

- Purpose and Problems of Periodontal DiseDocument9 pagesPurpose and Problems of Periodontal DiseNessrine AmiriNo ratings yet

- The Dental Anomaly: How and Why Dental Caries and Periodontitis Are Phenomenologically AtypicalDocument7 pagesThe Dental Anomaly: How and Why Dental Caries and Periodontitis Are Phenomenologically AtypicalNicolle DonayreNo ratings yet

- Nderstanding Periodontal Pathogenesis Is Key To Improving Management Strategies For This CommonDocument12 pagesNderstanding Periodontal Pathogenesis Is Key To Improving Management Strategies For This CommonMuhammad GhifariNo ratings yet

- OsteomieliteDocument12 pagesOsteomieliteDiegoSistoSeidlNo ratings yet

- Diagnostico PeriodontalDocument16 pagesDiagnostico PeriodontalLizeth GalvizNo ratings yet

- InTech-Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Periodontal DiseaseDocument18 pagesInTech-Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Periodontal DiseaseTrefina PranaNo ratings yet

- Controversies in Periodontology PDFDocument2 pagesControversies in Periodontology PDFSrivani PeriNo ratings yet

- Caranza Diagnosis EnglishDocument3 pagesCaranza Diagnosis EnglishZuwandi Abd KadirNo ratings yet

- Classification of Periodontal DiseasesDocument27 pagesClassification of Periodontal DiseasesbenazirghaniNo ratings yet

- Diploma de Endodoncia Online 18-19Document7 pagesDiploma de Endodoncia Online 18-19shivaniNo ratings yet

- 3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseDocument3 pages3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseEstherNo ratings yet

- Sindromi Pulpo - PeriodontalDocument12 pagesSindromi Pulpo - PeriodontalErisa BllakajNo ratings yet

- His To Pathological Features ofDocument10 pagesHis To Pathological Features ofEdric DjiemeshaNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Influence of Periodontal Treatment inDocument12 pagesA Review of The Influence of Periodontal Treatment inTran DuongNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Periodontal DiseaseDocument37 pagesRisk Factors For Periodontal DiseaseBelee Vera AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Artigo PeriodontiaDocument7 pagesArtigo PeriodontiaDANIELA MARTINS LEITENo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Periodontitis: Chapter 6Document30 pagesEpidemiology of Periodontitis: Chapter 6Atziry LopezNo ratings yet

- Definition and Nomenclature of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument9 pagesDefinition and Nomenclature of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseMaria Jose Contreras SilvaNo ratings yet

- Bartold Si Van Dyke 2013 Prd450Document15 pagesBartold Si Van Dyke 2013 Prd450ccyyppaaxxNo ratings yet

- Applied Sciences: The Link Between Periodontal Disease and Oral Cancer-A Certainty or A Never-Ending Dilemma?Document13 pagesApplied Sciences: The Link Between Periodontal Disease and Oral Cancer-A Certainty or A Never-Ending Dilemma?summayya kanwalNo ratings yet

- The Oral Microbiome in Periodontal DiseaseDocument16 pagesThe Oral Microbiome in Periodontal DiseaseAlan Roberto Flores GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Background: Staging and Grading of Periodontitis: Framework and Proposal of A New Classi!cation and Case De!nitionDocument37 pagesBackground: Staging and Grading of Periodontitis: Framework and Proposal of A New Classi!cation and Case De!nitionandrea guillénNo ratings yet

- Principles of Periodontology Dentino - Et - Al-2013-Periodontology - 2000Document38 pagesPrinciples of Periodontology Dentino - Et - Al-2013-Periodontology - 2000Denisa FloreaNo ratings yet

- Controversies in PeriodonticsDocument56 pagesControversies in PeriodonticsReshmaa Rajendran100% (1)

- Dental Clinics of North AmericaDocument204 pagesDental Clinics of North Americasam4slNo ratings yet

- Vander Velde N 2017Document21 pagesVander Velde N 2017Shinta Dewi NNo ratings yet

- Classification of Periodontal DiseaseDocument6 pagesClassification of Periodontal DiseaseMohammed HamedNo ratings yet

- AGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS: AN INTRODUCTIONDocument101 pagesAGGRESSIVE PERIODONTITIS: AN INTRODUCTIONdileep900No ratings yet

- Albandar 2002 Global Epidemiology OverviewDocument4 pagesAlbandar 2002 Global Epidemiology OverviewjeremyvoNo ratings yet

- Global Epidemiology of Periodontal Diseases: An Overview: J M. A & T E. RDocument4 pagesGlobal Epidemiology of Periodontal Diseases: An Overview: J M. A & T E. RkochikaghochiNo ratings yet

- Periodontitis and Systemic Disease: BDJ Team November 2015Document5 pagesPeriodontitis and Systemic Disease: BDJ Team November 2015Jenea CapsamunNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Endo LesionDocument7 pagesPeriodontal Endo LesionHenry MandalasNo ratings yet

- Retrospectiva Istorica Si Conceptele Actuale in Etiopatogenia Si Clasificarea Bolilor Parodontale. Date Din LiteraturaDocument14 pagesRetrospectiva Istorica Si Conceptele Actuale in Etiopatogenia Si Clasificarea Bolilor Parodontale. Date Din LiteraturaRoxana AngelescuNo ratings yet

- Academy Report: Diagnosis of Periodontal DiseasesDocument11 pagesAcademy Report: Diagnosis of Periodontal DiseasesJason OrangeNo ratings yet

- Research and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesDocument7 pagesResearch and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesParastikaNo ratings yet

- fileadminuploadsefpDocumentsCampaignsNew ClassificationGuidance Notesreport-02 PDFDocument9 pagesfileadminuploadsefpDocumentsCampaignsNew ClassificationGuidance Notesreport-02 PDFAufa AyshaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology Is The Study of Patterns ofDocument11 pagesEpidemiology Is The Study of Patterns ofAppas SahaNo ratings yet

- How To Diagnose and Treat Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions?: Literature Review ArticleDocument7 pagesHow To Diagnose and Treat Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions?: Literature Review ArticleMadrika YantiNo ratings yet

- 10 14219@jada Archive 1936 0430Document12 pages10 14219@jada Archive 1936 0430DavidNo ratings yet

- Preshaw 2018 Periodontology - 2000Document19 pagesPreshaw 2018 Periodontology - 2000Dr. DeeptiNo ratings yet

- Understanding the pathogenesis and progression of peri-implantitisDocument11 pagesUnderstanding the pathogenesis and progression of peri-implantitisMuhammad GhifariNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3 Ari.Document10 pagesArticulo 3 Ari.Alex EsquedaNo ratings yet

- Atherosclerosis 1Document10 pagesAtherosclerosis 1Gustivanny Dwipa AsriNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Magic Mouth and Genital Ulcers With IDocument4 pagesBreaking The Magic Mouth and Genital Ulcers With ILuisa VlahovićNo ratings yet

- (Angelo Mariotti) Enfermedades Gingivales Inducidas Por PlacaDocument11 pages(Angelo Mariotti) Enfermedades Gingivales Inducidas Por PlacaFrank A. IbarraNo ratings yet

- PEAK Is There A Link Between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular Disease PDFDocument12 pagesPEAK Is There A Link Between Periodontitis and Cardiovascular Disease PDFYama Piniel FrimantamaNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts in The Pathogenesis of Periodontitis: From Symbiosis To DysbiosisDocument20 pagesCurrent Concepts in The Pathogenesis of Periodontitis: From Symbiosis To DysbiosisgugicevdzoceNo ratings yet

- Comm Dent Oral Epid - 2006 - Fejerskov - Concepts of Dental Caries and Their Consequences For Understanding The DiseaseDocument9 pagesComm Dent Oral Epid - 2006 - Fejerskov - Concepts of Dental Caries and Their Consequences For Understanding The DiseaseDian MartínezNo ratings yet

- Classification of Periodontal DiseasesDocument15 pagesClassification of Periodontal DiseasescherrydsilvaNo ratings yet

- Global understanding of infective endocarditis from ICE investigationDocument18 pagesGlobal understanding of infective endocarditis from ICE investigationYampold Estheben ChusiNo ratings yet

- PericoronitisDocument6 pagesPericoronitisvapay9496No ratings yet

- 1 4954122304943554897Document445 pages1 4954122304943554897Hady SpinNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics: The Chairside Periodontal Diagnostic Toolkit: Past, Present, and FutureDocument23 pagesDiagnostics: The Chairside Periodontal Diagnostic Toolkit: Past, Present, and FutureDr.Niveditha SNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of periodontal disease among older adultsDocument18 pagesEpidemiology of periodontal disease among older adultsDiana Choiro WNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral PathologyDocument13 pagesReview Article: Oral Surgery Oral Medicine Oral PathologyAngelica RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Zoo 803 AssignDocument6 pagesZoo 803 Assignolayemi morakinyoNo ratings yet

- Bruxism-An Unsolved Problem in Dental MedicineDocument4 pagesBruxism-An Unsolved Problem in Dental Medicinedentace1No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S240566182100023X MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S240566182100023X MainJunior BonfáNo ratings yet

- Core Concepts in Clinical Infectious Diseases (CCCID)From EverandCore Concepts in Clinical Infectious Diseases (CCCID)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Nexus Between Tooth Decay, Liver Disease and Sugar IntakeDocument154 pagesThe Nexus Between Tooth Decay, Liver Disease and Sugar IntakeEmine Alaaddinoglu100% (2)

- Owbh PDFDocument55 pagesOwbh PDFEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Periodontics: Definitions, Anatomy, DiseasesDocument33 pagesIntroduction to Periodontics: Definitions, Anatomy, DiseasesEmine Alaaddinoglu100% (1)

- 1-s2.0-002239137290193X-maiFixed Partial Dentures and Operative DentistrynDocument4 pages1-s2.0-002239137290193X-maiFixed Partial Dentures and Operative DentistrynEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Composition and Development of Oral Bacterial CommunitiesDocument20 pagesComposition and Development of Oral Bacterial CommunitiesEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Etiology and Microbiology of Periodontal DiseasesDocument7 pagesEtiology and Microbiology of Periodontal DiseasesEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- The Periodontal Crown - Creating Healthy TissueDocument5 pagesThe Periodontal Crown - Creating Healthy TissueEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Rfe 311 315 Exam BankDocument9 pagesRfe 311 315 Exam BankEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- AbDocument12 pagesAbEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Systemic Medication and The Inflammatory CascadeDocument13 pagesSystemic Medication and The Inflammatory CascadeEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Cid 1Peri-Implantitis Versus Periodontitis: Functional Differences Indicated by Transcriptome Profiling2001Document11 pagesCid 1Peri-Implantitis Versus Periodontitis: Functional Differences Indicated by Transcriptome Profiling2001Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Flap Surgery 2Document45 pagesPeriodontal Flap Surgery 2Emine Alaaddinoglu100% (2)

- Antibiotic ResistanceDocument32 pagesAntibiotic ResistanceEmine Alaaddinoglu100% (2)

- DM PerDocument7 pagesDM PerEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Anova e PrintDocument3 pagesAnova e PrintEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Oral PathogensDocument35 pagesIntroduction To Oral PathogensEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- J DENT RES-2012-Miron-736-44Document10 pagesJ DENT RES-2012-Miron-736-44Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Bacterial Invasion of Host CellsDocument20 pagesBacterial Invasion of Host CellsEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Crestal Sinus Lift With Sequential Drills And.20Document1 pageCrestal Sinus Lift With Sequential Drills And.20Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Functional Electrical Stimulation Using Microstimulators To Correct Foot Drop: A Case StudyDocument9 pagesFunctional Electrical Stimulation Using Microstimulators To Correct Foot Drop: A Case StudyEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- J Dent Res 2012 Papapanou 907 8Document3 pagesJ Dent Res 2012 Papapanou 907 8Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Topics in Neuromodulation TreatmentDocument200 pagesTopics in Neuromodulation TreatmentJosé Ramírez100% (1)

- Armitage 1999 PDFDocument6 pagesArmitage 1999 PDFnydiacastillom2268No ratings yet

- 2945979248366223753Document6 pages2945979248366223753Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- 3D Finite Element Model and Cervical Lesion Formation inDocument7 pages3D Finite Element Model and Cervical Lesion Formation inEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Biofilm Dynamics at The GingivalDocument4 pagesBiofilm Dynamics at The GingivalEmine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- Academic Ranking of Turkish Universities January 20101Document35 pagesAcademic Ranking of Turkish Universities January 20101Emine AlaaddinogluNo ratings yet

- I Forgot My Password: LoginDocument6 pagesI Forgot My Password: LoginMithun ShinghaNo ratings yet

- Mobile NetDocument9 pagesMobile NetArdian UmamNo ratings yet

- Getting More Effective: Branch Managers As ExecutivesDocument38 pagesGetting More Effective: Branch Managers As ExecutivesLubna SiddiqiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Throughout The Life Span 8Th Edition Edelman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument30 pagesHealth Promotion Throughout The Life Span 8Th Edition Edelman Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDeborahAndersonmkpy100% (10)

- Helical Axes of Skeletal Knee Joint Motion During RunningDocument8 pagesHelical Axes of Skeletal Knee Joint Motion During RunningWilliam VenegasNo ratings yet

- Ear Discharge (Otorrhoea) FinalDocument24 pagesEar Discharge (Otorrhoea) Finaljaya ruban100% (1)

- Solids, Liquids and Gases in the HomeDocument7 pagesSolids, Liquids and Gases in the HomeJhon Mark Miranda SantosNo ratings yet

- Program Python by ShaileshDocument48 pagesProgram Python by ShaileshofficialblackfitbabaNo ratings yet

- A LITTLE CHEMISTRY Chapter 2-1 and 2-2Document5 pagesA LITTLE CHEMISTRY Chapter 2-1 and 2-2Lexi MasseyNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics and Social ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesBusiness Ethics and Social Responsibilitytitan abcdNo ratings yet

- The New York Times OppenheimerDocument3 pagesThe New York Times Oppenheimer徐大头No ratings yet

- EHV AC Transmission System Design and AnalysisDocument104 pagesEHV AC Transmission System Design and Analysispraveenmande100% (1)

- Behold The Lamb of GodDocument225 pagesBehold The Lamb of GodLinda Moss GormanNo ratings yet

- All About Mahalaya PakshamDocument27 pagesAll About Mahalaya Pakshamaade100% (1)

- Measurement Techniques Concerning Droplet Size Distribution of Electrosprayed WaterDocument3 pagesMeasurement Techniques Concerning Droplet Size Distribution of Electrosprayed Waterratninp9368No ratings yet

- 7310 Installation InstructionsDocument2 pages7310 Installation InstructionsmohamedNo ratings yet

- Metamorphic differentiation explainedDocument2 pagesMetamorphic differentiation explainedDanis Khan100% (1)

- 2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesDocument5 pages2022 Australian Grand Prix - Race Director's Event NotesEduard De Ribot SanchezNo ratings yet

- Pageant Questions For Miss IntramuralsDocument2 pagesPageant Questions For Miss Intramuralsqueen baguinaon86% (29)

- Federal Decree Law No. 47 of 2022Document56 pagesFederal Decree Law No. 47 of 2022samNo ratings yet

- Case Study: The Chinese Fireworks IndustryDocument37 pagesCase Study: The Chinese Fireworks IndustryPham Xuan Son100% (1)

- List of Licensed Insurance Intermediaries Kenya - 2019Document2 pagesList of Licensed Insurance Intermediaries Kenya - 2019Tony MutNo ratings yet

- IIT Ropar Calculus Tutorial Sheet 1Document2 pagesIIT Ropar Calculus Tutorial Sheet 1jagpreetNo ratings yet

- Abcdef Ghijkl Mnopq Rstuv Wxyz Alphabet Backpack Book Bookcase CalculatorDocument4 pagesAbcdef Ghijkl Mnopq Rstuv Wxyz Alphabet Backpack Book Bookcase Calculatornutka88No ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document20 pagesChapter 2Saman Brookhim100% (4)

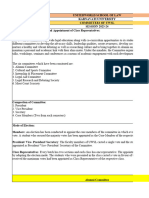

- Committees of UWSLDocument10 pagesCommittees of UWSLVanshika ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- NLE 08 Test IDocument7 pagesNLE 08 Test IBrenlei Alexis NazarroNo ratings yet

- Globalisation Shobhit NirwanDocument12 pagesGlobalisation Shobhit NirwankrshraichandNo ratings yet

- Electrical Power System FundamentalsDocument4 pagesElectrical Power System FundamentalsArnab BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization of Human Resource ManagementDocument12 pagesImpact of Globalization of Human Resource ManagementnishNo ratings yet