Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gioachino Rossini

Uploaded by

FREIMUZICCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gioachino Rossini

Uploaded by

FREIMUZICCopyright:

Available Formats

The Barber of Seville

Isabella Colbran Main article: The Barber of Seville Rossini's most famous opera was produced on 20 February 1816, at the Teatro Arge ntina in Rome. The libretto, a version of Pierre Beaumarchais' stage play Le Bar bier de Sville, was newly written by Cesare Sterbini and not the same as that alr eady used by Giovanni Paisiello in his own Barbiere, an opera which had enjoyed European popularity for more than a quarter of a century. Much is made of how qu ickly Rossini's opera was written, scholarship generally agreeing upon two or th ree weeks. Later in life, Rossini claimed to have written the opera in only twel ve days. It was a colossal failure when it premiered as Almaviva; Paisiello's ad mirers were extremely indignant, sabotaging the production by whistling and shou ting during the entire first act. However, not long after the second performance , the opera became so successful that the fame of Paisiello's opera was transfer red to Rossini's, to which the title The Barber of Seville passed as an inaliena ble heritage. Later in 1822, a 30-year-old Rossini succeeded in meeting Ludwig van Beethoven, who was then aged 51, deaf, cantankerous and in failing health. Communicating in writing, Beethoven noted: "Ah, Rossini. So you're the composer of The Barber of Seville. I congratulate you. It will be played as long as Italian opera exists. Never try to write anything else but opera buffa; any other style would do viol ence to your nature."[3] [edit] Marriage and mid-career

Caricature by H. Mailly on the cover of Le Hanneton, July 4, 1867 Between 1815 and 1823 Rossini produced 20 operas. Of these Otello formed the cli max to his reform of serious opera, and offers a suggestive contrast with the tr eatment of the same subject at a similar point of artistic development by the co mposer Giuseppe Verdi. In Rossini's time the tragic ending was so distasteful to the public of Rome that it was necessary to invent a happy conclusion to Otello . Conditions of stage production in 1817 are illustrated by Rossini's acceptance o f the subject of Cinderella for a libretto only on the condition that the supern atural element should be omitted. The opera La Cenerentola was as successful as Barbiere. The absence of a similar precaution in construction of his Mos in Egitt o led to disaster in the scene depicting the passage of the Israelites through t he Red Sea, when the defects in stage contrivance always raised a laugh, so that the composer was at length compelled to introduce the chorus "Dal tuo stellato soglio" to divert attention from the dividing waves. In 1822, four years after the production of this work, Rossini married the renow ned opera singer Isabella Colbran. In the same year, he moved from Italy to Vien na where his operas were the rage of the audiences. He directed his Cenerentola in Vienna, where Zelmira was also performed. After this he returned to Bologna, but an invitation from Metternich to the Congress of Verona to "assist in the ge neral re-establishment of harmony" was too tempting to refuse, and he arrived at the Congress in time for its opening on October 20, 1822. Here he made friends with Chateaubriand and Dorothea Lieven. In 1823, at the suggestion of the manager of the King's Theatre, London, he came to England, being much fted on his way through Paris. In England he was given a generous welcome, which included an introduction to King George IV and the recei pt of 7000 (530000 today) after a residence of five months. The next year he becam e musical director of the Thtre des Italiens in Paris at a salary of 800 (58000 toda y) per annum. Rossini's popularity in Paris was so great that Charles X gave him

a contract to write five new operas a year, and at the expiration of the contra ct he was to receive a generous pension for life. [edit]End of career

Gioachino Rossini, photographed by Flix Nadar, 1858 During his Paris years, between 1824 and 1829, Rossini created the comic opera L e comte Ory and Guillaume Tell (William Tell). The production of the latter in 1 829 brought his career as a writer of opera to a close. He was thirty-eight year s old and had already composed thirty-eight operas. Guillaume Tell was a politic al epic adapted from Schiller's play Wilhelm Tell (1804) about the 13th-century Swiss patriot who rallied his country against the Austrians. The libretto was by tienne Jouy and Hippolyte Bis (fr), but their version was revised by Armand Marr ast.[7] Photograph of Gioachino Rossini (Ransom Humanities Research Center, The Universi ty of Texas at Austin) The music is remarkable for its freedom from the conventions discovered and util ized by Rossini in his earlier works, and marks a transitional stage in the hist ory of opera, the overture serving as a model for romantic overtures throughout the 19th century. Though an excellent opera, it is rarely heard uncut today, as the original score runs more than four hours in performance. The overture is one of the most famous and frequently recorded works in the classical repertoire. In 1829 he returned to Bologna. His mother had died in 1827, and he was anxious to be with his father. Arrangements for his subsequent return to Paris on a new agreement were temporarily upset by the abdication of Charles X and the July Rev olution of 1830. Rossini, who had been considering the subject of Faust for a ne w opera, did return, however, to Paris in November of that year. Six movements of his Stabat Mater were written in 1832 by Rossini himself and th e other six by Giovanni Tadolini, a good musician who was asked by Rossini to co mplete the work. However, Rossini composed the rest of the score in 1841. The su ccess of the work bears comparison with his achievements in opera, but his compa rative silence during the period from 1832 to his death in 1868 makes his biogra phy appear almost like the narrative of two livesthe life of swift triumph and th e long life of seclusion, of which biographers give us pictures in stories of th e composer's cynical wit, his speculations in fish culture, his mask of humility and indifference. [edit]Later years His first wife died in 1845, and on 16 August 1846, he married Olympe Plissier, w ho had sat for Vernet for his picture of Judith and Holofernes. Political distur bances compelled Rossini to leave Bologna in 1848. After living for a time in Fl orence, he settled in Paris in 1855, where he hosted many artistic and literary figures. Rossini had been a well-known gourmand and an excellent amateur chef hi s entire life, but he indulged these two passions fully once he retired from com posing, and today there are a number of dishes with the appendage "alla Rossini" to their names that were either created by or specifically for him. Probably th e most famous of these is Tournedos Rossini, still served by many restaurants to day. In the meantime, after years of various physical and mental illnesses, he had sl owly returned to music, composing obscure little works intended for private perf ormance. These included his Pchs de vieillesse ("Sins of Old Age"), which are grou ped into 14 volumes, mostly for solo piano, occasionally for voice and various c hamber ensembles. Often whimsical, these pieces display Rossini's natural ease o f composition and gift for melody, showing obvious influences of Beethoven and C hopin, with many flashes of the composer's long buried desire for serious, acade mic composition. They also underpin the fact that Rossini himself was an outstan ding pianist whose playing attracted high praise from people such as Franz Liszt

, Sigismond Thalberg, Camille Saint-Sans and Louis Dimer.[8] He died at the age of 76 from pneumonia at his country house at Passy on Friday, 13 November 1868. He was buried in Pre Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France. In 18 87, his remains were moved to the Basilica di Santa Croce di Firenze, in Florenc e, at the request of the Italian government. [edit]Legacy According to Herbert Weinstock's 1968 biography,[9] the composer's estate was va lued at 2.5 million francs upon his death in 1868, the equivalent of about 1.4 m illion US dollars. According to one contemporary account, at the time of his dea th Rossini's estate yielded revenues of 150,000 francs per year.[10] Apart from some individual legacies in favour of his wife and relatives,[11] Rossini willed his entire estate to the Comune of Pesaro.[12] The inheritance was invested to establish a Liceo Musicale (Conservatory) in the town. When, in 1940, the Liceo was put under state control and turned into the Conservatorio Statale di Musica "Gioachino Rossini", the corporate body to which Rossini's inheritance had been conveyed, assumed the style of Fondazione G. Rossini. The aims of the institutio n, which is still in full activity, are to support the Conservatorio initiatives and to promote the study and the spread worldwide of the figure, the memory, an d the works of Rossini. The institution has collaborated since the beginning wit h the Rossini Opera Festival.[13] Rossini's estate also provided funding for the Prix Rossini, a prize to be award ed to young French composers and librettists. The provision took effect in 1878 on the death of his widow and was awarded by the Acadmie des Beaux-Arts. Prize-wi nning works were produced by the Socit des Concerts, Institut de France, from 1885 to 1911.[14] The bequest sought to reward composers of music which emphasized m elody, which Rossini wrote "today is neglected" ("melodia, oggi si trascurata"). The prize for librettists was to be given to writers that observed "the laws of morality, which the modern writers completely ignore" ("osservando le leggi del la morale di cui i moderni scrittori piu non tengono verun conto"). The prizes w ere exclusively for French composers and librettists ("exclusivamente per I Fran cesi").[15] [edit]Honors and tributes

Rossini's now-empty tomb at Pre Lachaise Cemetery in Paris Rossini was a foreign associate of the institute, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour and recipient of innumerable orders. Rossini's final resting place, in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence Immediately after Rossini's death, Giuseppe Verdi proposed to collaborate with t welve other Italian composers on a Requiem for Rossini, to be performed on the f irst anniversary of Rossini's death, conducted by Angelo Mariani. The music was written, but the performance was abandoned shortly before its scheduled premiere . Verdi re-used the "Libera me, Domine" he had written for the Rossini Requiem i n his 1872 Requiem for Manzoni. In 1989 the conductor Helmuth Rilling recorded t he original Requiem for Rossini in its world premiere. In 1900 Giuseppe Cassioli created a monument to Rossini in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.[16] [edit]Rossiniana Mauro Giuliani (who died in 1829) wrote six sets of variations for guitar on the mes by Rossini, Opp. 119124 (c. 1820-1828). Each set was called "Rossiniana", and collectively they are called "Rossiniane". This was the first known tribute by one composer to another using a title with the ending -ana. In 1925, Ottorino Respighi orchestrated four pieces from Pchs de vieillesse as the suite Rossiniana (he had earlier used pieces from the same collection as the ba sis of his ballet La Boutique fantasque).

[edit]Music

Portrait of Gioachino Rossini by Francesco Hayez, 1870 Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan According to the Oxford History of Western Music, "Rossini's fame surpassed that of any previous composer, and so, for a long time, did the popularity of his wo rks. Audiences took to his music as if to an intoxicating drug -- or, to put it more decorously, to champagne, with which Rossini's bubbly music was constantly compared."[17] Rossini took existing operatic genres and forms and perfected them in his own st yle. Through his own work, as well as through that of his followers and imitator s, Rossini's style dominated Italian opera throughout the first half of the 19th Century.[17] In his compositions, Rossini plagiarized freely from himself, a common practice among deadline-pressed opera composers of the time. Few of his operas are withou t such admixtures, frankly introduced in the form of arias or overtures. For exa mple, in Il Barbiere there is an aria for the Count (often omitted) "Cessa di pi resistere", which Rossini used (with minor changes) in the cantata Le Nozze di T eti e di Peleo and in La Cenerentola (the cabaletta for Angelina's rondo is almo st unchanged). Moreover, four of his best known overtures (La cambiale di matrim onio, Tancredi, La Cenerentola and The Barber of Seville) share operas apart fro m those with which they are most famously associated. A characteristic mannerism in Rossini's orchestral scoring is a long, steady bui lding of sound over an ostinato figure, creating "tempests in teapots by beginni ng in a whisper and rising to a flashing, glittering storm,"[18] which earned hi m the nickname of "Signor Crescendo". A few of Rossini's operas remained popular throughout his lifetime and continuou sly since his death; others were resurrected from semi-obscurity in the last hal f of the 20th century, during the so-called "bel canto revival." Rossini himself correctly predicted that his Barber of Seville would continue to find favor with posterity, telling a friend: One thing I believe I can assure you: that of my works, the second act of Guglie lmo Tell, the third act of Otello, and all of il Barbiere di Seviglia will certa inly endure. (Ma di una cosa credo potervi assicurare: che di mio rimarr di certo il secondo atto del Guglielmo Tell, il terzo atto dellOtello, e tutto il barbier e di Seviglia.)[19] [edit]

You might also like

- NabonidusDocument4 pagesNabonidusFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- NabonidusDocument4 pagesNabonidusFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- BabyloniaDocument6 pagesBabyloniaFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Tiger BodyDocument6 pagesTiger BodyFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- TinnitusDocument3 pagesTinnitusFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- The LionDocument4 pagesThe LionFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- GingivitisDocument3 pagesGingivitisFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Early Iron Age BabyloniaDocument10 pagesEarly Iron Age BabyloniaFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Republic of San MarinoDocument2 pagesRepublic of San MarinoFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- The Congress of BerlinDocument6 pagesThe Congress of BerlinFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- MyringotomyDocument2 pagesMyringotomyFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Pierre BoulezDocument14 pagesPierre BoulezFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- United States Electoral CollegeDocument5 pagesUnited States Electoral CollegeFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Bio FilmDocument7 pagesBio FilmFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- The California Gold RushDocument5 pagesThe California Gold RushFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- RameauDocument7 pagesRameauFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- ScarlattiDocument2 pagesScarlattiFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Richard WagnerDocument10 pagesRichard WagnerFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- AlbénizDocument3 pagesAlbénizFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Olympic Marketing Revenue Generation OverviewDocument1 pageOlympic Marketing Revenue Generation OverviewFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Bach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyDocument3 pagesBach's Influence on Four-Part HarmonyFREIMUZIC0% (1)

- MozartDocument6 pagesMozartFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- The Olympic Marketing Fact FileDocument1 pageThe Olympic Marketing Fact FileFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- MessiaenDocument4 pagesMessiaenFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Cossacks in The Russian EmpireDocument2 pagesCossacks in The Russian EmpireFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Romanian EconomyDocument3 pagesRomanian EconomyFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Historical Evolution of RomaniaDocument3 pagesHistorical Evolution of RomaniaFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Demographics of RomaniaDocument2 pagesDemographics of RomaniaFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Ural CossacksDocument1 pageUral CossacksFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Razin and Pugachev RebellionsDocument3 pagesRazin and Pugachev RebellionsFREIMUZICNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Landscape of The SoulDocument2 pagesLandscape of The SoulsdrgrNo ratings yet

- Prueba Sintesis 1roDocument2 pagesPrueba Sintesis 1roJocelyn Lissette Toledo ReyesNo ratings yet

- SynonimsDocument18 pagesSynonimsBenjaminBenNo ratings yet

- Tell AsmarDocument222 pagesTell Asmarjtg.jorgeNo ratings yet

- Breuer MarcDocument138 pagesBreuer MarcOctav AdrianNo ratings yet

- Montage in Architecture - A Critical and Creative Perception of Our Space in The EverydayDocument121 pagesMontage in Architecture - A Critical and Creative Perception of Our Space in The EverydaygmzokumusNo ratings yet

- The Mighty Brush Painting Guide Death Korps of Krieg 143rd LegionDocument20 pagesThe Mighty Brush Painting Guide Death Korps of Krieg 143rd LegionAitor RomeroNo ratings yet

- LSD Magazine - Issue 1 - No Permission No Control FinalDocument317 pagesLSD Magazine - Issue 1 - No Permission No Control FinalLSD (London Street-Art Design) Magazine100% (2)

- Ed304701 PDFDocument241 pagesEd304701 PDFcrytomaniaNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Finishing Russian Armor Vol.15 PDFDocument15 pagesStep by Step Finishing Russian Armor Vol.15 PDFmichael Dodd100% (5)

- Nippon Hydrophilic CoatingsDocument2 pagesNippon Hydrophilic Coatingsamit100% (1)

- Tekla Mdeling Guide 21.0Document306 pagesTekla Mdeling Guide 21.0Tân ĐạtNo ratings yet

- Tree Frog PDFDocument4 pagesTree Frog PDFFrauJosefskiNo ratings yet

- Saloni's Design PortfolioDocument30 pagesSaloni's Design PortfolioSaloni Saran100% (1)

- Helmholtz and The Tri-Stimulus TheoryDocument4 pagesHelmholtz and The Tri-Stimulus TheorydavidrojasvNo ratings yet

- Qcs 2010 Section 25 Part 1 General PDFDocument3 pagesQcs 2010 Section 25 Part 1 General PDFbryanpastor106No ratings yet

- Characteristics of Color ExplainedDocument16 pagesCharacteristics of Color Explainedabhinav_gupta_40No ratings yet

- Product CatalogDocument18 pagesProduct Catalogmanox007No ratings yet

- Personal Response Questions 400Document60 pagesPersonal Response Questions 400Anonymous wfZ9qDMNNo ratings yet

- Top Ten Secrets v3Document19 pagesTop Ten Secrets v3fajaruddinNo ratings yet

- Benetex Profile 2012 UpdatedDocument7 pagesBenetex Profile 2012 UpdatedManzur Kalam NagibNo ratings yet

- Webern's Drei Volkstexte Number 1: An AnalysisDocument16 pagesWebern's Drei Volkstexte Number 1: An AnalysisKyle VanderburgNo ratings yet

- Interior Decoration & FurnishingDocument120 pagesInterior Decoration & FurnishingMichael StephenNo ratings yet

- Building Materials: 1. Particle Board 2. Block BoardDocument31 pagesBuilding Materials: 1. Particle Board 2. Block BoardArnav DasaurNo ratings yet

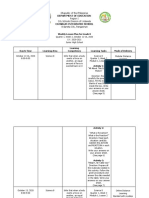

- Weekly lesson plans for Grade 8 and 10 science and MAPEH subjectsDocument14 pagesWeekly lesson plans for Grade 8 and 10 science and MAPEH subjectsMark Jay BongolanNo ratings yet

- Airbrush Step by Step - March 2015 EU PDFDocument72 pagesAirbrush Step by Step - March 2015 EU PDFJesus GamiñoNo ratings yet

- MOHR Corporate Design Guide for JPK LogoDocument24 pagesMOHR Corporate Design Guide for JPK LogosyahrainamirNo ratings yet

- SikaTop Armatec 110 EpoCemDocument3 pagesSikaTop Armatec 110 EpoCemseagull70No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Outdoor and IndoorDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Outdoor and Indoorapi-295499931100% (1)

- Blood and Ritual. Ancient Aesthetics in Feminist and Social Art in Latin America. Emilia Quiñones OtalDocument18 pagesBlood and Ritual. Ancient Aesthetics in Feminist and Social Art in Latin America. Emilia Quiñones OtalartecontraviolenciaNo ratings yet