Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Historical Linguistics 2010

Uploaded by

Si vis pacem...Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Historical Linguistics 2010

Uploaded by

Si vis pacem...Copyright:

Available Formats

Historical Linguistics of Biblical Hebrew An Outline*

Hebrew 298 Professor Ronald Hendel University of California, Berkeley Fall 2010

*Revised and abridged from handouts of Thomas O. Lambdin and John Huehnergard (Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, Harvard University) Revised 2010 Please do not cite without permission.

Contents

Preliminaries: The Semitic Language Family and Linguistic Reconstruction I. Phonology 1. The Overlay of Phonological Systems Alphabet Matres Lectionis Vowel Points Evidence for Non-Tiberian Phonology 2. Consonantal Changes Unconditioned Changes Conditioned Changes Sibilants: Phonetic Changes 3. Vowel Changes Original Long Vowels Diphthongs Original Short Vowels: Changes in Quantity a. Preliminaries: Syllables and Stress b. The Chain of Changes Original Short Vowels: Changes in Quality a. Three Laws Barths Law Qatqat > Qitqat Philippis Law b. Origins of Seghol (and Segholates) II. Nouns and Pronouns 1. Grammatical Features Case Number and Gender State Definiteness 2. Personal Pronouns and Pronominal Suffixes Independent Pronouns and Subject Suffixes (Nominative) Possessive Suffixes (Genitive) Object Suffixes (Accusative) 3. Other Pronouns (Demonstrative, Relative, Interrogative) 4 5 5

8 10 15

18 18

20

24

III. The Verbal System 1. Semantics of the Qal Stem Situation Tense Aspect Mood 2. The Proto-Northwest Semitic Verbal System: Qal Stem 3. Vowel Classes of the Sound Root: Qal Stem 4. The Qal Stem of Weak Roots I-Yod ()" II-Waw/Yod (Hollow) (", )" III-Yod ()" I-Nun ()" I-Guttural I-Aleph ()" Geminate Roots ()" 5. The Derived Stems Semantics of the Derived Stems a. Situation b. Voice Qal Passive (G-) Niphal (N) Piel (D) Pual (D-) Hiphil (C) Hophal (C-) Hithpael (Dt) Polel/Polal/Hithpolel Appendix 1: Contraction Concordance Appendix 2: Cognate Consonants Appendix 3: Review of A Grammar of Samaritan Hebrew Selected Bibliography

25 25

27 28 30

38

44 45 46 50

Preliminaries: The Semitic Language Family and Linguistic Reconstruction

figure: Semitic Language Family

Central Semitic innovations:

*qatala replaces perfective/preterite *yaqtul (vs. East Semitic) *yaqtulu replaces imperfective *yaqattal (vs. East Semitic and Ethiopian)

Linguistic Reconstruction house Akkadian Old South Arabic Ethiopic Arabic Ugaritic Hebrew Aramaic btum byt bet baytun bt bayit bt

Changes case ending: u (nominative) mimation/nunation: final m/n contraction of diphthong: ay anaptyctic vowel: i spirantization: t

I. Phonology

1. The Overlay of Phonological Systems

Alphabet borrowed from Phoenician represents // and //, may represent // and // Matres Lectionis (immt haqqer) 10th cent. B.C.E: no matres lectionis (inscriptions, from Phoenician) 9th cent. B.C.E.: innovation of final matres (perhaps from Aramaic) waw for final yod for final he for final , , (for the latter, e.g. , ) 8th cent. B.C.E.: innovation of medial matres waw for internal , (from contraction of diphthong, aw > ) yod for internal , (from contraction of diphthong, ay > ) 6th - 5th cent. B.C.E.: revision of final matres waw for final , he for final , 1st cent. B.C.E. C.E.: baroque orthography internal matres used for short vowels in some scribal traditions (sometimes in SP and Qumran) Vowel Points (niqqd) , ca. 8th-10th cent. C.E., Masters of Tradition. The most elaborate (and eventually dominant) system: Tiberian Masoretes, esp. Aharon Ben Asher. Evidence for Non-Tiberian Phonology Qumran Hebrew: matres lectionis in words like Samaritan Hebrew (reading tradition): madbar, bed, atti (2fs pronoun) Transcriptions in LXX, Origens Hexapla (secunda), Jerome, etc. = ; = ; = ( 2ms suff.); = note also = Babylonian and Palestinian vocalization systems Note also pausal system, probably dialectal or historically earlier, or some combination.

2. Consonantal Changes

Unconditioned Changes *d and *z merge to z PS *daqin*zayt> > (d = , pronounced as in thy) Heb. zqn zayit old olive

*t and * merge to PS *talt*im> >

(t = , pronounced as in thigh) Heb. l m three name

*, *, and * merge to PS *ar*qay*idq> > >

( = emphatic d; and = emphatic t) Heb. ere qayi edeq earth summer righteousness

* and * merge to PS *almat*ayn> > Heb. alm ayin young woman eye

* and * merge to PS * ami* adat> > Heb. m d five new

Notes on development: 1. The interdental mergers (#1-3) are attested in the Canaanite languages of the first millennium B.C.E. 2. The laryngeal/pharyngeal (guttural) mergers (#4-5) are attested in all of the NWS languages of the first millennium B.C.E., with some survivals (cf. Greek transcriptions).

Conditioned Changes Word-initial *w > y PS *wald- > PNWS *yaldPCS *wataba *yataba Exception: conjunction, wa-. Note that the phonetic value of w > v in postclassical Hebrew. Cf. Greek transcriptions of as (Clement) and (Origen). It is pronounced [w] by most mizrai Jews (influence of Arabic). Assimilation of nun. *nC > CC PS *yantin *bint> PNWS *yattin > > *bitt > Heb. yittn bat let him give daughter > > Heb. yeled yab boy sit

Quiescence of alep in syllable-final position. The alep is preserved in spelling. PS *ra*an> > *r() *()n > > Heb. r() ()n head sheep

Note the odd (hypercorrected) spellings in MT: *bir- > *b()r *dib- > *z()b *mud- > *m()d > > > ber zeb med well wolf very much

Syncope of intervocalic he and yod (syncope of yod = contraction of triphthong) *vhv2 > v2 *vya > *vyu > e *bahu (prep. + 3ms pron. suff) > > *yuhaqtilu (Hiphil impf.) *banaya *atiya *yitayu *yibniyu *adiyu *yibniyu > > > > > > bnh th yiteh yibneh deh yibn *bu *yaqtil he built he drank he will drink he will build field they will build > > b yaqtl

*vyv > v

But *ba + yad > beyd (preservation of morpheme boundary) Cf. Ugaritic and Phoenician bd Spirantization: b g d k p t develop postvocalic allophones (in Aramaic and Hebrew) PS *malk *anku > > Heb. melek nk king I

Notes on development: 1. Word-initial *w > y and assimilation of nun are PNWS changes. 2. Quiescence of alep is prior to the Canaanite shift. 3. Syncope of intervocalic he and yod is a first millennium NWS change. 4. Spirantization is post 6th cent. BCE, after Aramaic interdental shifts: *t (written with > )t and *d (written with > )d.

Sibilants: Phonetic Changes Original in was a lateral fricative [], pronounced like hl (cf. bem Greek balsam; kadim Akkadian kaldu), becomes [s] Original samekh was pronounced like [], as in check (Egyptian transcriptions) Original in was perhaps [s], as in Arabic, becomes [] In LBH, in and samekh coalesce to [s] (note graphic interchanges) ibblet vs. sibblet (Judges 12:6), probably [] vs. [], representing Cis- vs. Transjordanian dialectal pronunciations of in, prior to samekh > [s]

3. Vowel Changes

The original phonemic system in PS and PNWS has six vowels: long vowels: short vowels: a i u

Original Long Vowels Canaanite Shift: * > *talt*anku *bniyu > > > al nk bneh three I he builds, builder (pt.)

Note on development: Begins in southern Canaan in Late Bronze Age. Found in Amarna letter from Jerusalem (a-nu-ki = /ank/), but not in other Amarna Canaanite dialects and not at Ugarit (a-na-ku = /anku /, in syllabic transcription). Original * and * remain and (generally marked in MT by matres lectionis).

Diphthongs: aw and ay *aw is retained as we when stressed (with addition of unstressed anaptyctic vowel to break up consonant cluster) *mwt > mwet death

but contracts to when unstressed *mawt > mt my death

*ay is retained as ayi when stressed (with addition of unstressed anaptyctic vowel to break up consonant cluster) *byt *yn > > byit yin house eye, spring

but contracts to when unstressed *bayt *ayn > > bt n my house my eye

10

Notes on development: 1. Diphthongs always contract in Northern Hebrew (e.g., yn in Samaria Ostraca), similarly Ugaritic, Phoenician. 2. The contraction of diphthongs led to the reinterpretation of medial waw and yod in traditional spelling as matres lectionis for and , which then became generalized and extended (to all o-type and i-type vowels) in spelling practice. 2. Change of quality in stressed *yC > -yC, vowel dissimilation: *ssayk > sseyk (your horses)

Original Short Vowels: Changes in Quantity (= open and tonic syllables) Because of stress or phonetic changes, original short vowels can be lengthened, retained as short vowels (although not always the same vowel as the original), or reduced to vocal ewa (or a aeph vowel). Vocal ewa is always the product of reduction. *a *i *u lengthened retained a,i,e i,a,e u,o reduced (to ewa or aeph vowel) e or , e or , e or

The initial situation includes the loss of final short vowels, a late 2nd or early 1st millennium NWS change: *dabaru *dabarma *kataba *anti > > > > PH PH PH PH dabar dabarm katab att word, thing words, things he wrote you (2fs)

N.B. This change entails the loss of the case system.

a. Preliminaries: Syllables and Stress Syllables begin with a consonant. Open syllables in Biblical Hebrew are Cv (rare) and Cv. Closed syllables are CvC and CvC. At the end of a word, a closed syllable will end without a vowel point, e.g. . In the middle of a word, however, the Masoretes felt a need to put a vowel point at the end of a closed syllable, even though there is no vowel pronounced. They used the same symbol as the symbol for vocal ewa, hence the birth of . silent ewa, as in the middle of

11

Stress in Biblical Hebrew is almost always on the final syllable (or ultima). (The previous syllables are the penultima and the antepenultima.) The stressed syllable is known as the tone or tonic syllable. The syllable preceding the tone syllable is the pretonic syllable, and the one before that is the propretonic syllable. Exceptions to final syllable stress are things like some pronominal suffixes (with anceps vowels), locative he, segholates, and some forms of weak verbs. Tonic syllables can take almost any form: open: Cv (rare), Cv, or closed: CvC, CvC. Unaccented syllables: In BH, an unaccented short vowel can only occur in a closed syllable (CvC), e.g., midbr, sper. An unaccented long vowel can only be part of an open syllable. (There are only two exceptions to this: bttm, houses, and nn, ah please.) Original short vowels in originally open unaccented syllables must lengthen or reduce. (Remember that original long vowels always stay long.) The only confusing vowel with regard to syllabification is the qame. Since the qame can stand for short o or long , the only way to distinguish between the two is to know something of the history of the particular word, or to trust in the metheg, which almost always signifies that the qame is . The metheg is used fairly consistently in the Bible, but occasionally isnt used when it would be helpful, and so the best procedure is to know something of the word itself. For example, the only instance in which the sequence CCe turns up in a noun is before the 2ms suffix, as in , debrek, your word. Otherwise a consonant with a qame followed by a consonant and a ewa sign will always represent CoC in a noun form (including the infinitive construct when it is used as a noun, i.e., kotb, my writing). In verbs it is not that simple. This same grouping in a verb , kteb, for instance). Here, you just have to know, or you have usually means CCe ( to trust in the metheg. The aeph vowels are a problem, but a rule of thumb is to treat them (in the context of syllabification) as if they were regular ewas (sometimes vocal, sometimes silent).

b. The Chain of Changes Nouns (including verbal nouns) and finite verbs with pronominal suffixes Propretonic and pretonic syllables Propretonic reduction will take place wherever it can, i.e., wherever the propretonic syllable was a consonant plus an original short vowel. (Remember, original long vowels and diphthongs cannot reduce to ewa.)

12

Once propretonic reduction takes place, you must look at the original pretonic syllable. If it is a consonant plus an original short vowel (as in *dabarm and *zaqinm, below), we are left with an unaccented open syllable with a short vowel, impossible in Hebrew. The only two possibilities for such a syllable are reduction to vocal ewa and lengthening. If the syllable immediately preceding has already reduced to vocal ewa, as in the cases we are considering, the pretonic syllable must lengthen. (Two vocal ewas together in a word is an impossible situation.) *dabarm > *zaqinm > *katab + am > *debarm *zeqinm *ketabam > > > debrm zeqnm ketbm words, things old he wrote them

If propretonic reduction cannot take place (i.e. it is a closed syllable or a long vowel), see under pretonic reduction (below). In construct forms, assume that the tonic syllable is the first syllable of the following word. Propretonic reduction eventually goes to zero, not vocal ewa. *adaqat > *dabaray > *adqat *dabray > > idqat dibr righteousness of words of

(see further below, p. 15, *Qatqat > Qitqat) Different changes of *a,* i,* u in pretonic syllable a. *a always lengthens pretonically. *dabarm > *kawkabm > *yila + im > debrm kkbm yilm words, things stars he will send them

Note that in *dabarm the original propretonic is reducible, while in *kawkabm and *yilaim the original propretonic is irreducible. b. *i and *u in an originally open syllable either lengthen or reduce pretonically, depending on the propretonic syllable. If the propretonic is reducible, *i and *u will lengthen pretonically. *daqinm *gadulm > > zeqnm gedlm old big

If the propretonic is not reducible, *i and *u reduce to ewa pretonically (unlike *a, as noted above).

13

*yiktub + im > yiktebm *yintin + im > yittenm *madbit > mizbit

>

mizbet

he will write them he will give them altars

If there is no propretonic syllable, *i tends to lengthen, *u tends to reduce. *inab *gubla? > > nb gebal grape Byblos

Before an in the tone syllable, *i and *u both tend to reduce to ewa. *imr *bukur Tonic syllable a. *a almost always lengthens under stress *dabar > *katab + am > Exceptions: Short *a is retained in monosyllabic nouns that originally ended in a double consonant. *amm > am people In the 1cs object suffix on verbs, *a does not lengthen. *qatala + n > qeln he killed me b. *i and *u also generally lengthen under stress. *yiktub + im > *kabid > *gadul > *imm > *uzz > yiktebm kbd (adj.) gdl (adj.) m z he will write them heavy big mother strength dbr ketbm word, thing he wrote them > > mr bekr ass first born

Note that *i and *u lengthen even in nouns that originally ended in a double consonant, unlike *a (above)

14

Finite verbs without pronominal suffixes Pretonic and propretonic syllables In this category, it is the pretonic vowel which reduces whenever possible. This determines the quantity of the propretonic vowel. If the pretonic vowel can be reduced to ewa, it will, and the propretonic vowel will lengthen, if it can. *katab *yitib *yiktub *yintin > > > > *kateb *yieb yikteb yitten > > kteb yeb they wrote they will sit, dwell they will write they will give

But, if the pretonic syllable is not reducible (i.e., it is a closed syllable or has a long vowel), the propretonic vowel is reduced. *yudabbir *haqmt > > yedabbr he will speak hqmt I established e ( instead of wa because the h is a guttural)

If the pretonic is the first syllable in the word, the vowel is lengthened. *hiqm > *yasbb > Tonic syllable a. *a remains short *katab *yala > > ktab yila he wrote he will send hqm ysbb they established they will turn

b. *i and *u lengthen under stress *yantin *yaktub *qant > > > yittn yiktb qnt he will give he will write I am/became small

Note on development: The different changes in the finite verb versus the noun and verbs with pronominal suffixes (verby vs. nouny words) probably derive from an original difference in stress position, which has become effaced (probably original antepenultimate stress in finite verbs).

15

Original Short Vowels: Changes in Quality (= closed syllables) a. Three Laws (for conditioned changes of a ~ i) Barths Law. (Proto-Hebrew) *ya- > yi- in the preformatives of the Qal imperfect/jussive. Previously there were main patterns: *yaqtul, *yaqtil, *yiqtal. *yaktub *yantin > > *yiktub *yittin > > yiktb yittn

extended also to Niphal and Hithpael.: *yankatib > *yikkatib > yikktb *yatqattilu > *yitqattil > yitqattl The original yaC- is preserved in some weak root types: I-Guttural Geminate Hollow *yamudu *yasubbu *yaqmu > > > yamd ysb yqm vs. vs. *yizaqu > yezaq *yitammu > ytam

*Qatqt > Qitqt. In unaccented closed syllables, *a often becomes i, particularly when followed by *a in accented syllable. (Vowel dissimilation.) (Late change; not in Samaritan, Hexapla, or Babylonian vocalization, e.g. SH madbr; Hexapla , ) *madbar *malamat *adaqat *dabaray > > > > midbr milmh *adqat > idqat *dabray > *dabr > dibr (*maqtal nouns) (fem. *maqtalat nouns) (fs. construct of *qatalat) (mpl. construct of *qatal)

Notes on development: 1. The original form (*qat-) is preserved before gutturals and doubled consonants: mabr, mattn. 2. Segholates lack the dibr-type form: *malakay > *malkay > malk (not milk), probably due to the influence of forms like malk. 3. The Rule of ewa (*CeCe > CiC), a synchronic rule, probably derives from a reanalysis and generalization of some *Qatqat > Qitqat forms, such as: *dabaray > dibr. Dibr was at some point reanalyzed as deriving from *deber. This may be a reflex of the ms. construct debar (with propretonic reduction of the short a). Some such reanalysis led to the synchronic inference: *debe > dib, generalized as *CeCe > CiC.

16

Philippis Law: *Philppi > Philppi In accented, originally closed syllables, *i often becomes *a, particularly when followed by the ultima syllable. (Vowel dissimilation.) (Late change; not in Hexapla or Babylonian vocalization) *kabdt *dibbrt *hikbdt > > > kbdt dibbrt hikbdt (Qal stative) (Piel) (Hiphil)

N.B. Qatqat and Philippi are complementary: unaccented *CaC > CiC; accented *CC > CC; note that both are late changes.

b. Origins of Seghol (and Segholates) Segholates: *qatl, *qitl, *qutl Segholation breaks up consonant cluster (anaptyyxis): *qatl *qitl1 *qitl2 *qutl *malk *qibr *sipr *qud > > > > *mlek *qber *sper *qde > > > > mlek qber sper qde (assimilation) (assimilation) (lengthening) (lengthening) cf. malk, malkh qibr sipr qod

Weak roots: *qayl *qawl *qity *qitG *qaGl *qall *qill1 *qill2 *bayt *mawt *piry *zib *nar *amm *bint *imm > > > > > > > > byit mwet per zba nar am bat m (anaptyxis with i) (anaptyxis with a) (anaptyxis with a) bt mt piry zib nr amm bitt imm

Notes on development: 1. Singular and plural have different stems, perhaps a remnant of PS broken plurals: *malk*malak*sipr*sipar*qud*quda2. NWS mixing of *qatl ~ *qitl: e.g., malk ~ milk, ra ~ ri. 3. Irreconcilable developments for *qitl (qetel, qtel) and *qill (qal and ql). Some *qitl1 forms were originally *qatl. Other *qitl1 and *qill1 forms assimilated by analogy to *qatl and *qall, respectively. Cf. biforms in some nouns: neder, nder.

17

4. Dialectal variation: LXX , Hexapla , Samaritan mlek, Babylonian malak, cf. pausal mlek. Influence of gutturals: *i often goes to e before or after a guttural or re in an unstressed closed syllable: *GiC > GeC; *CiG > CeG *izr *itml *yizaq *markabat > > > > ezr (cf. sipr) etml *yezaq > yezaq *mirkbh > merkbh

Echo vowels (aeph, rather than silent ewa) often develop after a syllable-closing guttural, e.g., yezaq. Syllable-opening gutturals also produce aeph seghol (rather than vocal ewa) in some open syllables, e.g. *ilhm > lhm. Also: *a > e before virtually doubled guttural followed by : *CaG(G) > CeG(G): e.g., ew (his brothers), ed (one), hehrm (the mountains). Influence of liquids: *i > e in a stressed syllable before ll, mm, nn (liquids) *karmll *barzll *minmnn *katabtnna > > > > karml barzl mimmnn ketabtn orchard iron from me 2fp perfect

*i > e when the accent is retracted (to next word or previous syllable) *bin *yittin *yaim > > > bn (absolute) vs. ben (construct) yittn vs. yitten- (with maqqep) ym (jussive) vs. wayyem (conv. impf.)

Word-final *ayu and *iyu > e (contraction of triphthong, see above, p. 7) *yitayu *yibniyu *adiyu > > > yiteh yibneh deh

18

II. Nouns and Pronouns

1. Grammatical Features

The basic nominal inflection of PNWS is approximately as follows: sing. masc. nom. gen. acc. fem. nom. gen. acc. malkatuM malkatiM malkataM malaktuM malaktiM malaktiM malkatMi malkatayMi malkatayMi dabaruM dabariM dabaraM dabarMa dabarMa dabarMa dabarMi dabarayMi dabarayMi plural dual

M = m (mimation) or n (nunation) Mimation after a short vowel was lost early in NWS. It exists in Amorite, but not in Ugaritic. After a long vowel or diphthong, mimation varies with nunation in 1st millennium NWS (Aramaic and Moabite have nunation). Case (IBHS 8.1-2) nominative = subject of clause (malkuM halaka) genitive = after prepositions (la-malkiM); and nomen rectum of construct phrase: (baytu malkiM) accusative = direct object of clause (qaala malkaM) In the dual and plural, the genitive and accusative have a common set of endings, referred to as the oblique. Number and Gender (IBHS 6-7) The distinction of number is a natural kind, as the distinction of gender in animals. Hebrew preserves some (very old) word pairs that distinguish natural gender: m and b; tn (she-ass) and mr (he-ass). At some point the distinction of natural gender was extended to a distinction of grammatical gender.

19

The formal distinctions of number and gender in nouns (ms. *, fs. *at, mp.*, fp. *t) may derive, at least in part, from the subject suffixes on the predicate adjective (3ms. *, 3fs. *at, 3mp. *, 3fp. *; see below, B1). State (IBHS 13) The distinction between unbound and bound (i.e., absolute versus construct and suffixed forms) was originally signaled by the presence or absence of mimation/nunation. unbound ms. mp. mdual fs. fp. fdual dabaruM (~ iM, aM) dabarMa (~ Ma) dabarMi (~ ayMi) malkatuM (~ iM, aM) malaktuM (~ iM) malkatMi (~ ayMi) bound dabaru (~ i,a) dabar (~ ) dabar (~ay) malkatu (~ i,a) malaktu (~ i) malkat (~ay)

This system persisted after the loss of mimation/nunation after short vowels, though some of the contrasts were lost. With the loss of final short vowels and the attendent loss of the case system, a new system of contrasts arose in Hebrew, signaled by differences of accentuation and vocalization. unbound ms. mp. dual fs. fp. dbr debrm ydyim malkh melkt bound debar dibr yed malkat malkt

Notes on development: 1. The mp and dual forms are derived from the old oblique forms: mp unbound: *dabarma > *dabarm > debrm mp bound: *dabaray > *dabray > dabr > dibr (*Qatqat > Qitqat) dual: *yadaym(i) > ydyim 2. The mp bound form with possessive suffix derives from the dual bound oblique form: *dabaray + ya (1cs) > debray my words

20

3. The fp bound form with possessive suffix is doubly marked, with fp ending + dual oblique ending: *malakt > malkt + ay + ya (1cs) > malktay my queens

Definiteness The contrast of definite vs. indefinite did not exist in PS or early NWS. It is a secondary development in Central Semitic: Canaanite (Hebrew, Phoenician) Classical Arabic: Inscriptional Arabic: (Lihyanite, Thamudic) Aramaic: OSA: prefixed ha (+ doubling) prefixed alprefixed h-, hnsuffixed -a suffixed n, -hn

These definite articles probably derive from demonstrative pronouns (Rubin 2005: 65-86): this (near deixis) PS *hanni > PCS *han (cf. OB. annm, anntum) > ha + doubling that (far deixis) PS *ulli > PCS ul (cf. OB ullm, Heb. lleh) > al

2. Personal Pronouns and Pronominal Suffixes

Independent pronouns and subject suffixes (nominative) (IBHS 16.2) independent pronouns PS 1cs 2ms 2fs 3ms 3fs *an *ank *ant *ant *h/u *h/i Hebrew n nk atth att h h subject suffixes (on perfect) (originally on predicate adjective) PS *-k *-t *-t *-a/ *-at Hebrew -t -t -t - -h

21

1cp 2mp 2fp 3mp 3fp

*nin *antum() *antin(n) *h/um() *h/in(n)

nan attem atten hm, hmmh (*hn), hnnh

*-n *-tum() *-tin(n) *- *-

-n -tem -ten - -

N.B. The notation , , indicates an anceps vowel, whose derived forms may be long or short. A syllable with a historical anceps vowel is usually not accented. Notes on development: 1cs: Ugaritic has both an and ank. Classical Biblical Hebrew has both, LBH mostly n, Rabbinic Hebrew only n. The subject suffix -t (originally *-k) was probably formed by analogy with the -t of the 2ms and 2fs pronouns and the - of the 1cs pronominal suffix in the genitive and accusative. The - of the 1cs independent pronoun, n/nk, derives from the same analogy with the other 1cs suffixes. 2ms: The writing suggests ktabt. At Qumran sometimes written . 2fs: Seven times written , though pointed att. Occasionally the perfect is written with -, though pointed -t (ktabt). 3fs: In the Pentateuch the pronoun is written eleven times, pointed ( a qer perpetuum). This is probably a textual problem of graphic confusion (-). The archaic forms and are found in Qumran texts (archaizing or dialectal). 1cp: Five times the form nan occurs. The initial probably derives by analogy with the 1cs n. In Jer. 42:6, is written (ketib), but is read as nan (qer). The form n is normal in Rabbinic Hebrew. 2mp: The form attem was formed by analogy with 2fp atten < *attinn. Similarly, the subject suffix -tem was formed by analogy with 2fp -ten < *-tinn. 2fp: attnh/attnnh occurs four times. 3mp: The form hmma was formed by analogy with 3fp hnn < *hinn. 3fp: Note the Rabbinic Hebrew form hn, which does not occur in BH.

22

Possessive suffixes (genitive on nouns and prepositions) (IBHS 16.4) Possessive suffixes on the singular noun PS Proto-Hebrew Hebrew 1cs 2ms 2fs 3ms 3fs 1cp 2mp 2fp 3mp 3fp *-/-ya *-k *-k *-h *-h *-n *-kum() *-kin(n) *-hum() *-hin(n) *- *-ak() *-ik() *-uh() *-ah() *-in *-kimm *-kinn *-am/-himm *-an/-hinn - -ek -k or -k -h/ -h -n -kem -ken -m -n postvocalic - -k -k -h or w -h -n -kem -ken -hem or -m (rare) -hen

Notes on development: 2s and 3s: Note the vowel harmony in the Proto-Hebrew forms, based on the three original case vowels, -a, -i, -u. 2ms: The MT spelling suggests the pronunciation -k (= pausal vocalization in MT, and as vocalized in the Hexapla). Cf. the frequent spelling in the Dead Sea Scrolls. 2fs: The biform -k occurs five times (Northern dialect). 3ms: The older form -h (with final he mater) occurs over fifty times (e.g. ). The historical development of *uhu > (2ms) and *ah > (3fs) provides the probable origin of the use of he (by reanalysis) as a mater lectionis for final - and -. Later this dual signification was disambiguated by the use of waw as the mater for final -. 1cs: The final - was formed by analogy with the independent pronoun nan and the subject suffix -n. 2mp: The form -kem was formed by analogy with the 2fp -ken < *-kinn; cf. the parallel developments in the pronoun and subject suffix, above. 3mp and 3fp: The suffixes -m and -n must be the result of analogy among 3mp and 3fp object suffixes on the perfect: *qatalhum > *qatalm (reanalyzed as qatal + m) *qatal : *qatalm :: *qatala : *qatalam after loss of final short vowels, *qatalam reanalyzed as *qatal + am

23

Possessive suffixes on the plural noun The mp base form is the old dual oblique, *dabarayThe fp base form is the normal fp plus the dual oblique ending -ay, > *malktay1cs 2ms 2fs 3ms 3fs 1cp 2mp 2fp 3mp 3fp Proto-Hebrew *-ay + ya *-ay + k *-ay + k *-ay + h *-ay + h *-ay + n *-ay + kimm *-ay + kinn *-ay + himm *-ay + hinn Hebrew -ay -eyk -ayik (-ayk in N. dialect) -yw (-eyh in old poetry) -eyh -n (cf. -n on singular noun) -kem -ken -hem/-m (cf. m on singular noun) -hen

Object suffixes (accusative on verbs, , and ) The object suffixes are equivalent to the possessive (genitive) suffixes on the noun, except for the 1cs, -n, whose n derives by analogy with the 1cs independent pronoun. Object suffixes on the perfect: postconsonantal after 3fs (at-) 1cs 2ms 2fs 3ms 3fs 1cp 2mp 2fp 3mp 3fp -n -ek - k -/-h -h -n -kem --m -n -n -k -ek -h/- -h -n -kem -am -an postvocalic (with 2fs t-; 2mp t-) -n -k -k -h/-w -h -n -kem -m -n (cf. archaic -m, -m)

Object suffixes on the imperfect follow -- or -en(n)-. These were probably derived by analogy with III-Yod jussive and energic forms with object suffixes: *yabnih (jussive) *yabninh (energic) > > yibnh yibnnn (reanalyzed as yibn + h) (reanalyzed as yibn + enn)

24

3. Other Pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns (IBHS 17) zeh (rarely z), f. zt (rarely z) derive from PS *d (gen. *d, acc. *d), *dt lleh < *illay consists of the base ill-, found in Aramaic and Ethiopic, cf. Akkadian ullu and Arabic ulli rare: hallz, hallzeh, f. hallz Relative pronouns (IBHS 19) aer is derived from *atr-, a noun originally meaning place. Cf. Aramaic atr, Akkadian aru, Arabic atru a (archaic) is related to Akkadian a, and ultimately to the pronominal base of the 3rd person *u-, *izeh, z, z (demonstrative pronouns) also function as relative pronouns e in LBH is a reduced form (grammaticalization) of aer Interrogative Pronouns (IBHS 18) m (who) < miya (Amarna), cf. Ugaritic my mh (what) corresponds to Arabic m, Ugaritic mh

25

III. The Verbal System

1. Semantics of the Qal Stem

Situation (IBHS 22.2) The linguistic term, situation, while not entirely familiar to Semitists, covers a series of contrasts quite familiar, particularly that of dynamic (or fientic) vs. stative. Situation, as a linguistic category, refers to the inherent meaning of the circumstance signified by the verb. Situation is therefore a quality of the lexicalization of meaning. (Margins, 154) states are static, i.e. continue as before unless changed, whereas events and processes are dynamic, i.e. require a continual input of energy if they are not to come to an end. (Comrie, Aspect, 13) dynamic verbs in the Qal are either transitive or intransitive there are many other types of situation (often called Aktionsart or lexical aspect) see below, E.1a, for other dynamic situations in the derived stems Tense (IBHS 20.2) The system of relative tense, as with any tense system, involves the relationships among three temporal points: that of the speaker or speech-act (S), the event (E), and the reference point (R). In this manner ... a tense does not situate a process in time, but rather orders it relative to a point of reference. (Margins, 158) dynamic stative Perfect relative past relative non-future Imperfect relative non-past (present/future) relative future

N.B. In CBH, participle is tenseless, with imperfective aspect Aspect (IBHS 20.2) Aspect is concerned with the different ways of viewing the inner temporal constituency of a situation (Comrie), in contrast to tense which describes the temporal relations between an event, a speaker, and a reference point. The primary aspectual distinction that is grammaticalized in most languages is that of perfectivity vs. imperfectivity. In Bernard Comries formulation:

26

the perfective looks at the situation from outside, without necessarily distinguishing any of the internal structure of the situation, whereas the imperfective looks at the situation from inside, and as such is crucially concerned with the internal structure of the situation. Aspect is concerned with the differing perceptions of an event, either seen from without as a bounded whole (perfective) or seen from within as an unbounded process (imperfective). (Margins, 164) Perfect = perfective aspect Imperfect = imperfective aspect Mood (IBHS 20.2) Mood is generally defined as involving the speakers attitude or opinion toward a proposition. The major contrast in mood is between the indicative (or declarative) and the modal, in which the former is unmarked for mood and the latter is marked. Like tense and aspect, mood is a key dimension of the grammaticalization of meaning, but differs functionally in that ... modality ... does not relate semantically to the verb alone, or primarily, but to the whole sentence. This feature is of particular significance for Hebrew, since there is in many cases no contrast of verb for the semantic contrast of indicative vs. modal. (Margins, 169) modal includes two further sets of distinctions: deontic modality (speakers will, e.g. wish, command, permission, obligation) vs. epistemic modality (speakers knowledge or opinion about a proposition, e.g. doubt, belief) and real vs. unreal The distinction between deontic and epistemic modality in CBH is clearly shown in the difference betwen the modal use of the Volitionals and the Imperfect. The Volitionals are specialized for deontic modality, expressing wishes, commands, and the like, while the Imperfect may be used for either deontic or epistemic modality. Where the two overlap defines the category of deontic modality; where they diverge defines epistemic modality. (Margins, 170) In CBH the Perfect is used to indicate unreality in both deontic and epistemic modality. For deontic modality this includes wishes and requests. For epistemic modality this includes conditions and some kinds of questions. (vs. real, expressed by Imperfect and Volitionals) (Margins, 172)

27

2. The Proto-Northwest Semitic Verbal System: Qal Stem

Suffix conjugation Perfect: *qatvla v = a, i, u (= theme vowel)

Prefix conjugations Imperfect: *yaqtvlu (pl. -na) Jussive/Preterite: *yaqtvl (pl. -) Volitive: *yaqtvla, etc. Energic: *yaqtvlanna Imperative: *qutul, *qitil, *qatal (energic: *qutulanna) Participles (or verbal adjectives) Active participle: *qtilStative participle (or predicate adjective): *qatvlPassive participle: *qatl-, qatlInfinitives Infinitive absolute: *qatlInfinitive construct: *qatl- (bound form) or *qitl-, *qutl-

Notes on the Hebrew development: 1. The preterite *yaqtul was replaced by the perfect *qatala in most positions. It was retained, however, in past tense narrative after the conjunction wa-, the so-called converted usage: *wayyqtul. 2. *yaqtul was also retained as the jussive, as may be seen in contrasts such as yqm (*yaqmu) / yqm (*yaqum) 3. The volitive form is preserved only in the cohortative of the 1st person (eqtelh, niqtelh). It forms with the jussive what may be termed the volitive or injunctive paradigm, and owing to this fusion, jussive and cohortative forms are interchangeable in most constructions, including converted usage in past tense narrative. 4. The formal distinction between the jussive and the imperfect in inflection has been lost, except for some weak forms (see 2, above). The optional -n in Hebrew is derived from the imperfect form. 5. The -nn- appearing before the pronominal suffixes of the imperfect is probably to be taken back to the energic forms (see previously under pronominal suffixes). In view of the phenomenon of junctural doubling, we must posit a close relationship in pre-Hebrew between the energic and the volitive, i.e., naqtulanna (reanalyzed as) naqtula + na > niqtelh nn

28

a process which led to the isolation of the particle n. 6. The converted perfect in a future or habitual (i.e. imperfective) sequence is probably the result of several distinct forces: a. The perfect was originally not a verb but a predicate adjective or stative participle (qatil, qatul, qatal). The original meaning is still clear in the stative verbs (like kbd, zqn) and others related to them semantically (like zkar, yda), where the perfect often requires a present tense translation in English. b. The perfect was used in PNWS (at least) in both protasis and apodosis of conditional sentences (with reference to future time, at least from the reference point of the utterance). c. A kind of reverse analogy seems necessary to account for the converted perfect sequences of Hebrew. Thus, given the ambiguity of the perfect mentioned in (a) and (b) above, the sequence qatala wa-yaqtul apparently engendered its opposite yaqtulu wa-qatala where the perfect takes on not only the future function of the imperfect, but even its habitual past function (i.e. imperfective aspect), a meaning which was originally totally alien to the perfect (which has perfective aspect). 7. The infinitive construct *qatl > qetl, varies with *qutl when suffixed, *qutl > qotl. The I-yod roots have the *qitl form for the inf. cst.: ebet, ibt.

3. Vowel Classes of the Sound Root: Qal Stem

Vowel class refers to the patterned variation in the second (theme) vowel of the perfect and imperfect. On the preformatives of the imperfect/jussive, see Barths Law (p. 14). dynamic verbs *(a,u) *qatala, *yaqtulu *kataba *yaktubu > > ktab yiktb

The main dynamic type. *(a,i) *qatala, *yaqtilu *natana *yantinu > > ntan yittn

29

This originally common type became extinct in Hebrew with the exception of ntan/yittn and the types yab/yb, m/ym. Other *(a,i) verbs were reanalyzed as Hiphil. *(a,a)1 *qatala, *yiqtalu *lamada *yilmadu > > lmad yilmad

A very small original class, also kab/yikab and rkab/yirkab. Several weak roots tend to fall into this class. stative verbs *(i,a) *qatila, *yiqtalu *kabida *yikbadu > > kbd yikbad

The main stative type. As a result of Philippis Law (kbdt > kbdt), many of these went to *(a,a)2 *(u,a) *qatula, *yiqtalu *qauna *yiqanu > > qn yiqan

A small stative class. According to Arabic and Akkadian, may have originally been *(u,u). *(a,a)2 *qatala, *yiqtalu *gadala *yigdalu > > gdal yigdal

A small stative type, including original *(a,a), *(u,a), and *(i,a). The original*(i,a) class shows up frequently in pausal or presuffixal forms (or perhaps the result of analogical mixing): gdal, but gedlan (presuffixal) qrab, but qrbh (pausal) gbar, but gbr (pausal)

30

4. The Qal Stem of Weak Roots

Roots I-Yod ()" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,i) *wataba, *yatibu *wataba *yatibu *ytib *tib *tibt *(a,a)1 *wadaa, *yadau *wadaa *yada*da *dat stative *(i,a) *waina, *yiwanu *waina *yiwan*wian? > > yn *yiyan- > yan yean > > > > yda *yida > yda da daat > > > > > yab *yitib > yb *yitib > yeb b ebet perfect imperfect jussive imperative infinitive construct

1. All but a few of these verbs were originally I-Waw; the change of #w- > #y- is PNWS. 2. Verbs originally I-Waw fell into two groups already in PS: (a) those having root allomorphs without the initial w- and (b) those without this allomorph. This root allomorphism, e.g., wtb ~ tb, is extremely old (attested in Egyptian) and the reason for it cannot be determined. The root allomorph without initial w- is found in the *(a,i) and *(a,a) classes in forms such as *yatib- (not *yawtib-) and *tib (not *witib), etc. 3. The rare *(a,u) type survives only in the I-yod-ade roots, e.g. yaq, yiq. These have an unusual development in the imperfect, where *w > . The assimilation of waw to a following dental may be a Proto-Semitic rule. Other originally *(a,u) verbs were interpreted as Hiphil, e.g. ysp, where the jussive *yawsup > *ysip (dissimilation of two utype vowels) > ysep, but perfect ysap (Qal). 4. The imperfect/jussive contrast is preserved in the *(a,i) type: yb/yeb (and wayyeb).

31

5. Some *(a,i) verbs became *(a,a)1 class because of the influence of gutturals; cf. dh, which reflects *di6. Note that the infinitive construct of the type ebet is originallly a feminine segholate noun (*qitl), *tibt > ebet. 7. The verb hlak falls in with the main I-Yod type *(a,i): hlak, ylk, lk, leket. 8. The verb ykl (was able) probably derives from the *yaqtul preterite of khl, *yakhul > ykl, and reanalyzed as a perfect. The imperfect ykal probably derives from the Qal passive *yukhal.

Roots II-Waw/Yod (Hollow) (", )" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,u) *qama, *yaqmu *qama *yaqmu *yaqum *qm *(a,i) *ama, *yamu *ama *yamu *yaim *m *(a,a)1 *baa, *yabu *baa *yabstative *(i,u) *mita , *yamtu *mita *yamtu *yamut > > > mt ymt ymt (wayymot) > > b yb > > > > m ym ym (wayyem) m > > > > qm yqm yqm (wayyqom) qm

32

*(u,a)

*bua, *yibu *bua *yib> > b yb

1. The immediate antecedents of the two main types in Hebrew *(a,u) and *(a,i) are often adduced as an argument for biconsonantal roots in PS, but because these same roots are treated as triconsonantal in East Semitic and elsewhere, no economy of reconstruction is gained by adopting a biconsonantal theory. Note that the vowel contrast of imperfect/jussive is explicable as a result of contractions in triconsonantal roots (see below, #3). 2. It appears that all *(a,u) verbs are from roots II-Waw and all *(a,i) verbs are from roots II-Yod. But the survival of other vowel classes (regardless of the middle consonant) suggests a more normal distribution at an earlier state of PS. 3. The triliteral theory requires that the prefix conjugation types *yaqmu/*yaqum, *yamu/*yaim, etc., arose from such forms as *yaqwum-, *yayim-, etc., which contracted differently in open and closed syllables: II-Waw imperfect *yaqwumu > jussive *yaqwum > *yaqmu *yaqum II-Yod *yayimu *yayim > > *yamu *yaim

The perfect also shows differences in vowel length, presumably deriving from differing contractions: *qawama > Proto-Heb *qama, Proto-Aramaic *qma, Arabic qma, Ethiopic qma Note that *awa should contract to * (see p. 7); it contracts to *a in Proto-Hebrew perhaps by analogy with the sound root *qatala. In view of these differing forms, a triliteral theory with contractions is preferable to a biconsonantal theory.

33

Roots III-Yod ()" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,i) *banaya, *yabniyu *banaya *yabniyu *yabniy *bini stative *(i,a) *bakiya, *yibkayu *bakiya *yibkay*yibkay > > > bkh yibkeh ybk (wayybk) > > > > bnh yibneh yiben (wayyiben) benh

1. Hebrew has leveled through a single paradigm for the perfect and imperfect. The imperfects converge in form, since both *iyu and *ayu > e. This provides a trigger for the mixing of perfect forms. In the perfect, note that the -- in bnt, -t, -t, -n, -tem, and ten reflect the original *(i,a) class (*bakiyt > bkt). 2. The 3fs perfect has an extra feminine suffix, probably by analogy with the sound root 3fs perfect (qtelh < *qatal + at). This extra suffix preserves the distinction with the 3ms perfect (bnh): 3fs *banayat > *banat + at = banatat > bneth Note that *aya should contract to * (see p. 7); it contracts to *a perhaps by analogy with the sound root 3fs *qatalat. 3. The contrast between imperfect and jussive is maintained from PS: imperfect *yabniyu jussive *yabniy > > yibneh *yibni > *yibn > yben

But note that a few verbs do not have anaptyxis in the jussive, e.g., ybk; yt. 4. As noted previously, the object suffixes on the imperfect in Hebrew derive from the IIIYod jussive and energic forms: *yabnih (jussive) *yabninh (energic) > > yibnh yibnnn (reanalyzed as yibn + h) (reanalyzed as yibn + enn)

34

Roots I-Nun ()" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,u) *napala, *yanpulu *napala *yanpul*nupul *(a,a)1 > > > npal yippl nepl

*nagaa, *yingau *nagaa *yinga*naga > > nga yigga ga

*(a,i)

*natana, *yantinu *natana *yantin*nitin > > ntan yittn t n

1. In the *(a,a)1 class the imperative and infinitive construct have assimilated to the I-Yod type. See below (#3) for this analogy. imperfect yb yigga imperative b ga infinitive construct ebet geet

2. lqa has assimilated to the *(a,a)1 class of I-Nun roots in the imperative and infinitive construct: imperfect imperative infinitive construct yiqqa qa (also leqa) qaat 3. In general, the I-Nun, I-Yod, and geminate roots show considerable mixing. I-Nun I-Yod Gem. imperfect yippl yigga yiq ysb/yissb ytam/yittm imperative nepl ga aq/yeq sb infinitive construct nepl geet eqet sebb/sb tm normal *(a,u)

35

The secondary forms probably derive from analogies, perhaps triggered by the unusual IYod imperfect type yiq; cf. the imperfect yir (from yr and nr); see above, Roots IYod, #3, and below, Geminate Roots, #4).

Roots I-Guttural Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,u) *amada, *yamudu *amada *yamud*umud stative *(a,a)2 *azaqa, *yizaqu *azaqa *yizaq*izaq > > > zaq yezaq zaq > > > mad yamd md

1. The difference in the vowels of the prefix conjugations reflects the original contrast of verbal prefixes (Barth-Ginsberg): *yamud-, yizaq-. The initial ayin prevented the normal assimilation of ya- > yi-. 2. The plural types yaamd and yeezq have been affected by a variant of the Rule of Shewa, in which the aeph changes into the corresponding short vowel, e.g.,*CCe > CaC: *yamud > *yamed > yaamd *yizaq > * yezeq > yeezq 3. The I-et forms vary in their use of aeph vowels, e.g., yezaq, yekam (both *a,a), and yaml, yab, yalm (all *a,u). One also finds variation within a root, e.g., yalm but yalem. For other I-Gutturals, note yahpk but ehpk, yazor but wayyazer, etc. 4. The I-Guttural roots with III-Yod preserve the *ya/*yi contrast in the prefix conjugations as well as the imperfect/jussive contrast: *(a,i) imperfect jussive *yaliyu *yaliy > > yaleh yaal (wayyaal)

36

*(i,a)

imperfect jussive

*yirayu *yiray

> >

yereh *yir

>

yiar (wayyiar)

Roots I-Aleph ()" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,u) *asara, *yasuru *asara *yasur*usur stative *(i,a) *amia, *yimau *amia *yima*ama > > m yema ma > > > sar yesr sr

1. I-Aleph roots are a subdivision of I-Guttural. The *(i,a) imperfect yema is substantially identical to yezaq. 2. The *(a,u) imperfect yesr (3mp yaasr) involves a peculiar rule associated with aleph and the following -- (< *u): the disappearance of the -- by reduction produces a reversion to the I-Guttural type, yaasr yaamd. The imperfect yesr was probably reformed on the basis of the imperative sr. Hence, for the imperfect: *yasur > *yasr yesr. 3. The weak *(a,u) type, with quiescent aleph in the prefixed forms: imperfect *yamuru jussive *yamur > > *y()muru > *y()mur > *ymuru > ymar *ymur > *ymir > wayymer

The change of *ymur- to ymar (imperfect) and *ymir (jussive) is dissimilatory, avoiding two u-type vowels in sequence (*ymr). Cf. the infinitive construct, lmr.

37

Geminate Roots ()" Main vowel classes dynamic *(a,u) *sababa, *yasubbu *sababa *yasubb*subb? stative *(i,a) *tamima, *yitammu *tamima *yitamm> > *tamma ytam > tam > > > sbab ysb sb

1. The perfect has a linking vowel -- < * after the geminated consonant and before a subject suffix with a consonant (i.e. 1st and 2nd person forms): sabbt, sabbt, sabbt,... sabbn, sabbtem/ten tammt, tammt, tammt,... tammn, tammtem/ten. This is probably related to the -- linking vowel in the Akkadian pars--ta, and in some Arabic dialects. 2. The distinction between sbab and tam points to a different treatment of *a as opposed to *i, *u in C2vC2v sequences: *sababa > sbab *tamima > *tamma > tam 3. In the imperfect the geminated consonant gave rise to a reformation of the vocalic pattern, where C2vC2 > vC2C2: *yasbub*yitmam> > *yasubb*yitamm> > ysb ytam

4. There are several I-Nun type biforms in the imperfect (see above, I-Nun): ysb and yissb ytam and yittm and yittam (probably originally a Niphal) The imperative sb may have triggered this analogy: ga : yigga :: sb : yissb

38

5. The Derived Stems

Semantics of the Derived Stems a. Situation To the extent that verbs of the derived stems have a semantically predictable relationship to one another and to the simple (Qal) stem, they may be schematized as follows: Situation of Qal 1. 2. 3. Factitive/Resultative/Intensive Piel (factitive; +1 arg.) Piel (resultative/intensive) Hiphil (transitive; +1 arg.) Hiphil (doubly trans.; +1 arg.) Causative

Stative Dynamic-intransitive Dynamic-transitive

Factitive = a construction in which a cause produces a state (IBHS, 691) Causative = a construction in which a cause produces an event (IBHS, 691) Resultative = the bringing about of the outcome of the action designated by the base root (IBHS, 400) This scheme is somewhat idealized and does not include a large number of verbs arising from other less clear derivational processes. Some examples of this scheme: 1. Qal stative ml (be full) dn (be fat) Qal intransitive b (come) npal (fall) Qal transitive bar (break) zrh (scatter) Qal transitive kal (eat) nhal (inherit) Piel (factitive, dynamic, +1 argument) mill (fill, make full) din (fatten, make fat) Hiphil (causative, transitive, +1 argument) hb (bring, cause to come) hippl (cause to fall) Piel (resultative/intensive, transitive) ibbr (make broken, smash) zr (make scattered, disperse) Hiphil (causative, doubly transitive, + 1 argument) hekl (feed, cause X to eat Y) hinl (cause X to inherit Y)

2.

3a.

3b.

In this model the Hiphil is associated with transitive and intransitive dynamic verbs, and the Piel with stative verbs and dynamic-transitive verbs. This is statistically so, but secondary use of these forms has tended to erase these original distinctions. That is, Hiphil forms are fairly common from stative roots (in which case Piel and Hiphil are virtually synonymous). Many Piel forms from dynamic roots are denominative, de-adjectival, or

39

de-participial cf. brk (passive participle) and brk (Piel) and are fairly easy to distinguish from the original group. b. Voice (IBHS 21.2) active Qal Piel Hiphil medio-passive Qal passive and Niphal Pual Hophal reflexive Niphal Hithpael Hithpael

Although the real system is far from clear, in early Semitic there were at least three ways to express the medio-passive of a corresponding active verb: (1) the internal passive (Qal Passive, Pual, Hophal); (2) the forms with prefixed -t-, designated Gt (Grundstamm), Dt (doubled), and Ct (causative; of which only the Hithpael survives in Hebrew); and (3) the form with a prefixed -n-, designated N, apparently only derivable from the G verb. Notes on these three types: 1. Internal Passive. It is possible that the internal passives were originally merely the stative form of a dynamic transitive verb, and only secondarily did the active and passive forms split into two independent systems. 2. Forms with prefixed -t-. It is probable that every dynamic transitive verb, whether G, D, or C, had corresponding -t- forms, expressing the reflexive/reciprocal or middle meaning of the verb. In Aramaic and Ethiopic these -t- forms took over the role of the passive, with the complete loss of the internal passive. In Arabic, Akkadian, and to a lesser extent Hebrew, the -t- forms remain distinct from the passive system, but their function in each language is somewhat different. 3. The N verbs, on the other hand, seem definitely to be associated with the G verb. They are probably originally part of the G system, and their full inflection too may be a secondary development. It is possible that the N form originally produced a dynamic intransitive verb relative to a dynamic transitive verb, and that the coalescence with the medio-passive/reflexive systems above was secondary. In Hebrew the Qal passive became obsolete, surviving forms being taken by the grammarians as Pual or Hophal. The Niphal, while retaining its old role as an intransitive verb, also took over the function of the passive. The three -t- forms, Gt, Dt, and Ct became obsolescent as derived forms, but survived in a merged type, Dt (Hithpael), as isolated lexical items. To judge from the popularity of the Hithpael in post-biblical Hebrew, it is likely that it had a more vigorous existence in other dialects of Hebrew during the early phases of the language.

40

Qal Passive (G-) (IBHS 22.6) perfect imperfect *qutala *yuqtal > > quttal (should be qtal) yuqtal

The perfect form with reduplication of the second consonant is probably the result of misconstrual as a Pual . (Cf. forms like sbab which were reinterpreted as Polal, see below, p. 43.) Note that the imperfect falls together with the Hophal. Some examples are: perfect imperfect luqqa, yullad, ukkal, hrag yuqqa, yuttan, yuqqam (nqm)

Many Niphal imperfects in the earlier books are probably Qal Passive imperfects, e.g., ywld (yllad), pointed yiwwald. Eventually the Niphal subsumes the semantic role of the Qal Passive (see above).

Niphal (N) (IBHS 23) perfect imperfect jussive imperative *naqtala *yanqatilu *yanqatil *inqatil? > > > > niqtal yiqqtl yiqqtl hiqqtl

The change in the perfect from *naqtal to niqtal is apparently due to the *qatqat > qitqat dissimilation. The change of the prefix vowel in the imperfect from *yaC to yiC is probably a generalization of the Barth-Ginsberg change of *yaC > yiC in the Qal. The imperative form with initial h- is probably formed by analogy with the Hiphil imperative: H jussive: imperative :: N jussive : imperative *yaqtil : *haqtil :: *yiqqatil : *hiqqatil

Piel (D) (IBHS 24) perfect imperfect jussive imperative *qattila *yuqattilu *yuqattil *qattil > > > > *qittil > qittl yeqattl yeqattl qattl

The earliest form of the perfect cannot be reconstructed with certainty; Arabic and Ethiopic suggest *qattala, while Hebrew and Aramaic suggest *qattila. The best solution is that

41

*qattala > *qattila by paradigmatic leveling of -aC1C1i- from the imperfect *yuqattilu. The change from *qattil > *qittil is obscure (*CaCCiC > CiCCiC). Note the influence of Philippis Law in the 1st and 2nd person perfect forms: *dibbirt > dibbart, etc. In II-Guttural roots (including re in this instance), compensatory lengthening is normal with re, aleph, and usually ayin, since these consonants do not double. So-called virtual doubling is common with he and et: *barrika *aita Pual (D-) (IBHS 25) perfect imperfect *kuttaba > *yukuttabu > kuttab yekuttab > > *birrika *iita > > *birik > brk it (virtual doubling)

Note that roots II-Guttural show the same variations between compensatory lengthening and virtual doubling as the Piel: *burraka Hiphil (C) (IBHS 27) perfect imperfect jussive imperative *haqtila *yuhaqtilu *yuhaqtil *haqtil > > > > *hiqtil *yaqtil *yaqtil haqtl > hiqtl (not hiqtl) yaqtl (not yaqtl) yaqtl > *burak > brak

The first problem here is the same as the Piel: Arabic and Ethiopic suggest a base form *haqtala for the perfect, while Hebrew and Aramaic suggest *haqtila. Probably *haqtala > *haqtila by the influence of -aCCi- from the imperfect *yuhaqtilu. The change from *haqtil > *hiqtil is obscure, as in the Piel (*CaCCiC > CiCCiC). Note that the *ha- of the perfect is preserved in I-yod roots: hld < *hawlida. The major problem is, of course, the long vowel -- in the perfect hiqtl and the imperfect yaqtl. The only possible source for this is by analogy with the Hiphil forms of Hollow roots (II-waw/yod), e.g., hqm/ yqm: perfect imperfect jussive *haqma *haqimt *yuhaqmu *yuhaqim > > > > *hiqm *hiqimt *yaqm *yaqim > > > > hqm hiqamt (Philippi) > hqamt yqm yqm

42

Note the alternation between -- and -i- in the Hollow forms; this is original with this system, the long vowel occurring in open syllables and the short vowel in closed syllables (see above). At some point in the development of the Hiphil of sound roots, the following analogical changes took place: 1cs perfect : 3ms perfect :: 1cs perfect : 3ms perfect *hiqimt : *hiqm :: *hiqtilt : *hiqtl 3ms jussive : 3ms imperfect :: 3ms jussive : 3ms imperfect *yaqim : *yaqm :: *yaqtil : *yaqtl Note that the distinction between languages with H-causative vs. -causative corresponds to the distribution of 3rd person pronouns with h or *hua vs. *ua, etc. (see p. 19). Hophal (C-) (IBHS 28) perfect imperfect *huqtala > *yuhuqtalu > hoqtal yuqtal

Note that the initial vowel in the perfect alternates between u/o. Hithpael (Dt) (IBHS 26) perfect imperfect jussive imperative *hitqattila *yatqattilu *yatqattil *hitqattil > > > > hitqattl *yitqattil *yitqattil hitqattl > > yitqattl yitqattl

The perfect and imperative forms were probably originally *taqattila and *taqattil, which would yield *taqattl. The forms with initial h- were probably reformed by analogy with the Hiphil jussive : imperative (cf. the development of the Niphal imperative). H jussive : imperative :: Ht jussive : imperative *yaqtil : *haqtil :: *yitqattil : *hitqattil Note the generalization of Barth-Ginsberg, *ya > yi, in the imperfect, as in the Niphal imperfect. Note the metathesis with a root beginning with a sibilant, *hitammira > hitammr, and the metathesis plus assimilation with a root beginning with an emphatic, *hitaddiqa > hiaddq (t > ), or a dental, *hitzakkira > hizdakkr (tz > zd). The form hitaaweh is probably not originally a Hithpael, but a t of wy.

43

Polel/Polal/Hithpolel The equivalent of Piel/Pual/Hithpael from hollow and geminate roots. perfect imperfect Polel qmm yeqmm Polal qmam yeqmam Hithpolel hitqmm yitqmm

Either a retention of an old stem type otherwise unknown, or generated by reanalysis of the Qal Passive as a new form, Polal (passive stem), and analogical creations of Polel (active stem) and Hithpolel (reflexive stem): Qal Passive of sbb *subaba *yusabbu > sbab *yusubab > yesbab

The imperfect *yusabb- probably changed to yusubab by analogy with the perfect *subab. With the demise of Qal Passive, sbab, yesbab were reanalyzed as new passive stem, the Polal. The active Polel was generated by analogy with Polal (and the of the Polel imperfect by analogy with tone vowel of the Piel). The reflexive Hithpolel was generated similarly. Hollow roots were drawn into this paradigm by mixing/analogy with geminate roots.

44

Appendix 1: Contraction Concordance

Triphthongs (with he, yod) [see p. 7] *vhv2 > v2 *vya > *vyu > e *bahu > *yuhaqtilu > *banaya *atiya *yitayu *yibniyu *adiyu *yibniyu > > > > > > > *bu *yaqtil bnh th yiteh yibneh deh yibn > b yaqtl

*vyv > v

N.B. *ba + yad

beyd (preservation of morpheme boundary)

Diphthongs (with waw, yod) [see p. 9] *aw > we when stressed: *mawt > mwet *aw > when unstressed: *mawt > mt *ay > ayi when stressed: *bayt > *ay > when unstressed: *bayt > bayit bt death my death house my house > sseyk your horses

N.B. change of quality in stressed *yC > -yC: Old Contractions in II-Waw/Yod verbs [see p. 31]

*ssayk

*wu > in originally open syllable: *yaqwumu > *yaqmu *wu > u in originally closed syllable: *yaqwum > *yaqum *yi > in originally open syllable: *yayimu > *yi > i in originally closed syllable: *yayim > *yamu *yaim

*awa > a: *qawama > *qama (perhaps by analogy with *qatala) *iyi > i: *iyima > *ima

45

Appendix 2: Cognate Consonants

labials

dentals

interdentals

sibilants

palatal

guttural

liquids

PS

p b m

t d t d t d t d t d t d t d t d t d

s z s z s z s z

k g q k g q k g q k g q

h h h h h h h h

l n r l n r l n r l n r l n r l n r l n r l n r l n r

Akk. p b m Ug. p b m

d/ / z z

Heb. p b m Ph. p b m

s z /s k g q k g q k j q k g q k g q

Aram. p b m Arab. f b m Eth. f b m

t[] d[z] [] [q] s z s z z s z s s z s s z

OSA p b m

N.B. Old Aramaic graphemes are indicated by brackets [x], prior to the consonantal mergings of later Aramaic dialects. N.B. For some clarification of the sibilant situation, see p. 8.

46

Appendix 3

A Grammar of Samaritan Hebrew: Based on the Recitation of the Law in Comparison with the Tiberian and other Jewish Traditions, by Zeev Ben-ayyim. Author: Hendel, Ronald

Article Type: Book review Publication: Hebrew Studies 43 (2002), pp. 240-44 A GRAMMAR OF SAMARITAN HEBREW: BASED ON THE RECITATION OF THE LAW IN COMPARISON WITH THE TIBERIAN AND OTHER JEWISH TRADITIONS. By Zeev Ben-ayyim. Revised Edition in English. Pp. xviii + 491. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2000. Cloth, $50.00. The study of Hebrew and its history is considerably enriched by the appearance of the English translation of Ben-ayyim's magisterial Grammar of Samaritan Hebrew. It appeared in Hebrew in 1977 as volume 5 of Ben ayyim's The Literary, and Oral Traditions of the Samaritans (Jerusalem: Academy of the Hebrew Language, 1957-1977). Ben-ayyim is widely acknowledged as the leading scholar of Samaritan Hebrew, and this volume has already achieved the status of a classic. The dissemination of his decades of study and massive erudition will be greatly facilitated by this careful and authoritative translation, which also includes some clarifications and minor restructuring. Abraham Tat, another distinguished scholar of Samaritan studies, helped to shepherd this translation project to fruition (and is so acknowledged on the title page), and assistance was also given by a number of other eminent Hebrew linguists in Israel. Samaritan Hebrew is essentially a literary dialect, more precisely, a reading tradition of a particular text, the Samaritan Pentateuch. (There are also Samaritan prayers and liturgical texts composed in this literary dialect.) This linguistic tradition has been preserved and transmitted in a particular community--the Samaritan community in and around Shechem/Nablus--over the last (approximately) 2200 years. There is no doubt that the Samaritan reading tradition has changed somewhat over that time, just as the parallel Tiberian reading tradition has changed somewhat. There is also no doubt that Samaritan Hebrew preserves linguistic traits that were shared by other Hebrew dialects in the late Second Temple Period, and is therefore rooted in a Hebrew vernacular of this period. The Hebrew of the Dead Sea Scrolls shows a number of traits that are also found in Samaritan Hebrew, but not in Tiberian Hebrew, thus demonstrating the antiquity of these aspects of Samaritan Hebrew. The textual fixity of the Samaritan Pentateuch has served in some cases as a preservative agent for this reading tradition, since sometimes the distinctive forms (vis a vis Tiberian He-

47

brew) are fixed in the consonantal text, for example, the second feminine singular personal pronoun , vocalized atti (versus Tiberian Hebrew , att). Most of the time, however, the reading tradition has been preserved solely in Samaritan oral tradition. (Note that the vernacular tongue among the Samaritans is Arabic, and in earlier times was Aramaic.) Hebrew probably ceased being a vernacular in the late Second Temple period or shortly thereafter. Ben-ayyim succinctly states his evidentiary sources and their ancient roots: This description is based on the language-type reflected in their [i.e., the Samaritans] Torah reading, which I heard and learned from priests and other experts of various ages. This reading links up with one of the final stages of Hebrew speech development prior to its cessation in ancient times. His volume is therefore a work of ethnolinguistic research on a current community and a complex discussion of the linguistic history of Hebrew from ancient times. The plan of this volume follows conventional grammatical categories: Phonology (pp. 2995), Morphology [of the Verb] (pp. 96-224), Pronoun (pp. 225-239), Noun (pp. 240-304), Numerals (pp. 305-312), Particles (pp. 313-322), and Some Points of Syntax (pp. 323-332). The author adds a useful Epilogue (pp. 323-344), which catalogues some of the connections between Samaritan Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew and between Samaritan Hebrew and Jewish Aramaic. There follows a comprehensive Inventory of Forms (pp. 345-464), which catalogues all the nouns and verbs of Samaritan Hebrew according to their morphological pattern. There are numerous cross-references, the volume is well-organized, and the discussions are marked by meticulous attention to details and methodological circumspection. The following are some gleanings from Ben ayyim's treasure trove. I have selected a few features of Samaritan Hebrew that are of particular interest to Hebrew specialists--dialectal features that differ from the comparable features in Tiberian Hebrew and that arguably stem from relatively early times. None of them are distinctively Late Biblical Hebrew developments (such as weakening of gutturals, disuse of internal passives and infinitive absolutes, collapse of the Classical Hebrew tense/aspect system, and increased use of participles, all amply attested in Samaritan Hebrew). These features likely derive from the period of Classical Hebrew and are preserved in Samaritan Hebrew and, in some cases, other non-Tiberian Hebrew dialects. These details will give a sense of the importance of Samaritan Hebrew--and of Ben-ayyim's massive contribution--to our understanding of the history of Hebrew. (In the following, SH = Samaritan Hebrew, TH = Tiberian Hebrew, DSS = Dead Sea Scrolls, LBH = Late Biblical Hebrew.) 1. Diphthongs (1.4.4). As one would expect, SH falls on the northern side of the north/south isogloss in the treatment of diphthongs. In Hebrew inscriptions from the north, diphthongs always contract, for example, q (*q) in the Gezer calendar and yn (*yn) in the Samaria ostraca versus qyi and yyin in TH and yyn in an Arad ostracon. In SH, one finds contracted forms such as bit/bet (vs. TH byit), mot (vs. TH mwet), and n (vs. TH yin). Curiously, one also

48

finds such SH forms as yayyen, with doubled middle radical, instead of the expected *yn (vs. TH yyin). 2. Canaanite Shift (1.5.2.4-7). In some cases, SH preserves the original *, where one would expect it to have turned to by the Canaanite Shift. So one finds nki (vs. TH nk) from original *anku; l (vs. TH l) from original *al; l (vs. TH l) from original *l; and k (vs. TH k) from original *k. Ben ayyim thinks that the Canaanite shift might originally have been conditioned by stress or position in word sequence, and that these are remainders from old biforms. 3. Pronouns (3.1) and Pronominal Suffixes (2.0.13; 3.2). The second feminine singular pronoun is atti (vs. TH att) from *ant (the final i is an anceps vowel, meaning there were ancestral biforms with long and short i). Interestingly, the consonantal form occurs seven times in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible, though vocalized as TH att. As one would expect, in SH the second feminine singular subject suffix on the perfect also has the form -ti. The second masculine plural pronoun is attimma (vs. TH attem), both from *attimm (which was formed by analogy with the second feminine plural pronoun *attinn). The consonantal form is also found in texts from the DSS. In SH the second masculine plural subject suffix on the perfect also has the form -timma. Other pronominal suffixes also preserve some interesting dialectal forms, for example, the second masculine singular accusative pronominal suffix -k/k (post-consonantal/postvocalic, respectively) (vs. TH -ek/k) from *-ak. The SH type of pronunciation is reflected in the normal biblical writing - (and is once pointed -k in TH, Ps 53:6), and is preserved also in the Greek transcription in the Hexapla, -. It is also equivalent to the TH pausal forms bk, lk, tk. 4. *Qatqat > qitqat (4.2.3). The dissimilation of short *a in unaccented closed syllables in words of this pattern is a late TH phenomenon and is not found in SH (nor in Babylonian Hebrew or Hexaplaric transcriptions). For example, SH madbr (vs. TH midbr) from *madbar; maqd (vs. TH miqd) from *maqda; ba (vs. TH ib) from *abat. 5. Philippi's Law (1.5.2.1, 2.1.2-3). The dissimilation of short *i in accented, originally closed syllables (*Philippi > Philppi) occurs regularly in monosyllabic words in SH but not always in polysyllabic. For example, bat (= TH) from original *bint; lab (vs. TH lb) from *libb. In polysyllabic words, Philippi's Law operates in forms like zqnti (= TH zqant) from *zaqint But Philippi's Law did not affect Piel qattilti (vs. TH qittalt) from original *qattilt, and Hiphil aqtilti (vs. TH hiqtalt) from original *haqtilt. Ben ayyim notes that SH preserves the original form in the Piel and Hiphil, perhaps reinforced by the equivalent Aramaic forms.

49

6. Segholate nouns (4.1.3). In SH the segholate nouns (*qatl, *qitl, *qutl became bisyllabic (as in TH), but retain a reflex of the original vowel more often than TH. Thus *malk becomes mlek in SH (vs. TH melek); *nap becomes nfe (vs. TH nepe); *qat becomes qet (vs. TH qeet). Note that qtel is commonly the pausal form in TH (e.g., npe, qet), probably retaining a dialectal variant. For *qitl forms, *idq becomes deq in SH (vs. TH edeq); *bin becomes ben (vs. TH been). Note that TH also has the development *qitl > qtel, for example, *sipr > sper. Obviously, there were alloforms of segholate nouns in various Hebrew dialects (note forms like in the Hexaplaric transcription, vs. TH ebed, SH bed). 7. Penultimate stress (1.4.6-8). Ben-ayyim argues that penultimate stress in many SH forms is a relatively late development, after a period in which it, like TH, had (with a few exceptions) ultimate stress. It is possible, however, that in verbs penultimate stress reflects the earlier Hebrew situation, which was unchanged in SH and other dialects. Whether early or late, several forms in SH have analogues in pausal forms in TH and in DSS forms. Examples are the Qal perfect second feminine singular form, SH qtl (vs. TH qtel), from *qatalat. The SH form is equivalent to the TH pausal form qtl. In the Piel imperfect third masculine plural, the SH form is yqattlu (vs. TH yeqattel) from *yuqattil. The SH form is similar to the TH pausal form yeqattl. There is evidence of penultimate stress in DSS in forms like ( vs. TH yiqtel) from *yaqtul. The DSS form is the same as the TH pausal form yiqt1. Penultimate stress versus ultimate stress seems to have varied according to dialects in Late Biblical Hebrew, each apparently preserving earlier traits. In sum, this volume is a magnificent contribution to Hebrew scholarship. Ben-ayyim notes that several reviewers of the original Hebrew edition recommended that the work be made available in a European language, and twenty-three years later he and his team have made good on this desideratum. Ben-ayyim has devoted his scholarly life to studying the Samaritan tradition of Hebrew and Aramaic, and his monumental labor and erudition have earned the gratitude of us all.

Ronald Hendel University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720

COPYRIGHT 2002 National Association of Professors of Hebrew

50

Selected Bibliography

Historical Linguistics Bloomfield, Leonard. Language History. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1965. Campbell, Lyle. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction. 2nd ed.; Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004. Historial Linguistics of Biblical Hebrew Blau, Joshua. Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew: An Introduction. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2010. Lambdin, Thomas O., and John Huehnergard. The Historical Grammar of Classical Hebrew: An Outline. Cambridge, Mass., 1998. Unpublished course handout. Senz-Badillos, Angel. A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. [HHL] Biblical Hebrew Syntax Waltke, Bruce K. and Michael OConnor. An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1990. [IBHS] Central and Northwest Semitic Garr, W. R. Dialect Geography of Syria-Palestine: 1000-586 B.C.E. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985; rpt, Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2004. Huehnergard, John. Features of Central Semitic. Pp. 155-203 in Biblical and Oriental Essays in Memory of William L. Moran, ed. A. Gianto. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 2005. Phonology: Sibilants Faber, Alice. Semitic Sibilants in an Afro-Asiatic Context. JSS 29 (1984) 189-224. Hendel, Ronald. Sibilants and ibblet (Judges 12:6). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 301 (1996): 69-75. Steiner, Richard. The Case for Fricative-Laterals in Proto-Semitic. New Haven: AOS, 1977.

51

Phonology: Original Short Vowels Blake, Frank R. Pretonic Vowels in Hebrew. JNES 10 (1951) 243-55. Garr. W. R. Pretonic Vowels in Hebrew. VT 2 (1987) 129-53. Phonology: Three Laws Hasselbach, Rebecca. The Markers of Person, Gender, and Number in the Prefixes of GPreformative Conjugations in Semitic. JAOS 124 (2004) 2335. (Barths Law) Blake, Frank R. The Apparent Interchange Between a and i in Hebrew. JNES 9 (1950) 76-83. (Qatqat > Qitqat) Lambdin, Thomas O. Philippis Law Reconsidered. Pp. 135-45 in Biblical Studies Presented to Samuel Iwry, ed. A. Kort and S. Morschauser. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1985. Nouns and Pronouns Fox, Joshua. Semitic Noun Patterns. HSS 59. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2003. Rubin, Aaron. Studies in Semitic Grammaticalization. HSS 57. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2005. Verbs Hendel, Ronald. In the Margins of the Hebrew Verbal System: Situation, Tense, Aspect, Mood. Zeitschrift fr Althebraistik 9 (1996) 152-81. Huehnergard, John. Hebrew Verbs I-w/y and a Proto-Semitic Sound Rule. Pp. 457-74 in Memoriae Igor M. Diakonoff, eds. L. Kogan et al. Winona Lake: Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2005. Jenni, Ernst. Das hebrische Piel. Zurich: EVZ-Verlag, 1968. Kouwenberg, N. J. C. Gemination in the Akkadian Verb. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

You might also like

- Ancient Hebrew MorphologyDocument22 pagesAncient Hebrew Morphologykamaur82100% (1)

- Phonology of Ancient Hebrew - VowelsDocument55 pagesPhonology of Ancient Hebrew - VowelsPiet Janse van Rensburg100% (1)

- Ancient Hebrew Language HistoryDocument72 pagesAncient Hebrew Language Historyאלינה דרימר100% (2)

- A Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookFrom EverandA Is for Abandon: An English to Biblical Hebrew Alphabet BookNo ratings yet

- Temporal Clause-NiccacciDocument5 pagesTemporal Clause-NiccacciJosé Estrada Hernández100% (2)

- Ehll Phonology BH PDFDocument12 pagesEhll Phonology BH PDFНенадЗекавицаNo ratings yet

- An Easy Practical Hebrew Grammar MasonVol1 PDFDocument625 pagesAn Easy Practical Hebrew Grammar MasonVol1 PDFafflanteNo ratings yet

- Proofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enDocument11 pagesProofs Biblical Hebrew Periodization enChirițescu Andrei100% (1)

- Passive in HebrewDocument11 pagesPassive in Hebrewovidiudas100% (1)

- John Huehnergard - An Annotated BibliographyDocument21 pagesJohn Huehnergard - An Annotated BibliographyAntonio Tavanti100% (2)

- Spirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdDocument330 pagesSpirit of Hebrew Po 02 HerdfcocajaNo ratings yet

- Course Hebrew SyntaxDocument146 pagesCourse Hebrew Syntaxacadjoki100% (2)

- Verbal Forms in Biblical Hebrew Poetry P PDFDocument352 pagesVerbal Forms in Biblical Hebrew Poetry P PDFCarlosAVillanueva100% (1)

- Basic HebrewDocument6 pagesBasic HebrewNatalieRivkahAlexander0% (1)

- Notes on Samuel Text and TopographyDocument543 pagesNotes on Samuel Text and Topographyclopotel1No ratings yet

- MasoraDocument16 pagesMasoraSebastian Massena-WeberNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Present Tense Copular ConstructionDocument33 pagesHebrew Present Tense Copular Constructionwolf-hearted0% (1)

- Pinnock - Bible - 2000 PDFDocument11 pagesPinnock - Bible - 2000 PDFJosh BloorNo ratings yet

- Wijnkoop. Manual of Hebrew Syntax. 1897.Document234 pagesWijnkoop. Manual of Hebrew Syntax. 1897.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Biblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualDocument13 pagesBiblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualcamaziNo ratings yet

- Tregelles. Hebrew Reading Lessons: Consisting of The First Four Chapters of The Book of Genesis, and The Eighth Chapter of The Proverbs. 1860?Document106 pagesTregelles. Hebrew Reading Lessons: Consisting of The First Four Chapters of The Book of Genesis, and The Eighth Chapter of The Proverbs. 1860?Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (3)

- The Hebrew Verbless ClauseDocument35 pagesThe Hebrew Verbless ClauseNauff ZakariaNo ratings yet

- The Enigma of the Masoretic TextDocument26 pagesThe Enigma of the Masoretic TextAnonymous mNo2N3100% (1)

- Masoretic PunctuationDocument26 pagesMasoretic PunctuationBNo ratings yet

- Prepositions Hebrew PDFDocument2 pagesPrepositions Hebrew PDFBenjamin Gordon100% (1)

- PAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical HebrewDocument25 pagesPAT-EL NA'AMA DiachBH 2012 Syntactic Aramaisms As A Tool For The Internal Chronology of Biblical Hebrewivory2011No ratings yet

- Lambdin - Hebrew GrammarDocument503 pagesLambdin - Hebrew GrammarViktor Ishchenko75% (4)

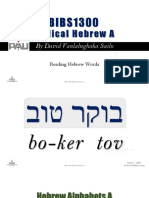

- BIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDocument35 pagesBIBS1300 02C Reading HebrewDavidNo ratings yet

- Nathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureDocument272 pagesNathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureBibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaNo ratings yet

- Gaonic CorrespondenceDocument7 pagesGaonic Correspondencephilip shternNo ratings yet

- Chapter Six: The Infinitive AbsoluteDocument16 pagesChapter Six: The Infinitive Absolutesteffen hanNo ratings yet

- SteinerDocument45 pagesSteinererikebenavrahamNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Grammar Davidson PDFDocument264 pagesHebrew Grammar Davidson PDFvictor100% (1)

- Biblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFDocument245 pagesBiblical Hebrew Grammar Presentation PDFNana Kopriva100% (2)

- Hebrew LanguageDocument16 pagesHebrew LanguageJay RonssonNo ratings yet

- Hebrew PDFDocument51 pagesHebrew PDFMath MathematicusNo ratings yet

- Thesis (Complete)Document87 pagesThesis (Complete)Johnny HannaNo ratings yet

- BINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFDocument246 pagesBINS 146 Peters - Hebrew Lexical Semantics and Daily Life in Ancient Israel 2016 PDFNovi Testamenti Lector100% (1)

- A Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?Document9 pagesA Student's Introduction To Biblical Hebrew: What Are The Essential Features That You Need To Memorize in Chapter 1?ajakukNo ratings yet

- Niccacci-BH Verbal SystemDocument21 pagesNiccacci-BH Verbal Systemclaudia_graziano_3100% (2)

- Targum & Masora: Does Targum Jonathan Follow The Madinhae' Readings of Ketiv-Qere?Document20 pagesTargum & Masora: Does Targum Jonathan Follow The Madinhae' Readings of Ketiv-Qere?AardendappelNo ratings yet

- Scholarly Transliteration of HebrewDocument2 pagesScholarly Transliteration of Hebrewoarion_hunterNo ratings yet

- Nicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFDocument152 pagesNicolls-A Grammar of The Samaritan Language-1838 PDFphilologusNo ratings yet

- Dempster - Torah and TempleDocument34 pagesDempster - Torah and TempleMichael Morales100% (1)

- 1.4 Hebrew Guttural LettersDocument2 pages1.4 Hebrew Guttural LettersScott SmithNo ratings yet

- Nderstanding Rabbinic Midrash/: Texts and CommentaryDocument11 pagesNderstanding Rabbinic Midrash/: Texts and CommentaryPrince McGershonNo ratings yet

- OTHB 5300 Intro Hebrew GrammarDocument9 pagesOTHB 5300 Intro Hebrew GrammarDavi ChileNo ratings yet

- Learning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyDocument4 pagesLearning Hebrew Letters, Vowels and VocabularyjoabeilonNo ratings yet