Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Icu

Uploaded by

Peace Andong PerochoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Icu

Uploaded by

Peace Andong PerochoCopyright:

Available Formats

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) Practice Alert Addresses Alarm Fatigue in ICU

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) 2013 National Teaching Institute and Critical Care Exposition. Sunday June 23, 2013

Hospitals need to minimize the risk associated with the ubiquitous patient safety issue of alarm fatigue, which has again been singled out by the ECRI Institute as the top technology hazard for 2013. The institute is a federal patient safety organization of the US Department of Health and Human Services. "We all know there are a lot of devices in the ICU everybody's on a monitor, and a lot of other devices at the bedside have alarms on them," said Marjorie Funk, PhD, RN, professor at the Yale School of Nursing in New Haven, Connecticut. "The problem now is that a lot of patients outside the ICU are on monitors and other devices, and many of the alarms produced are false," she told Medscape Medical News. Dr. Funk discussed the issue of alarm fatigue at the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) 2013 National Teaching Institute and Critical Care Exposition in Boston, Massachusetts. During her presentation, Dr. Funk listed contributors to the cacophony of alarm sounds on a hospital unit, which include infusion pumps, feeding devices, ventilators, and monitors. In addition, the battery-operated telemetry monitors frequently used outside the ICU have alarms to indicate a low battery, she noted. The staffs become overwhelmed by the sheer number of alarms and can miss or have a delayed response to alarms. In fact, it's estimated that approximately 90% of alarms in various ICU settings are either false or insignificant, according to a series of studies. Over time, "the staff becomes overwhelmed by the sheer number of alarms," Dr. Funk said, "and can miss or have a delayed response to alarms that can lead to sentinel events or patient death." One key way to reduce alarm fatigue is to eliminate unnecessary monitoring wherever possible. As part of the PULSE trial, Dr. Funk and her team evaluated the use of electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring in cardiac units. They found that 26% of more than 4300 patients on monitors did not meet American Heart Association practice standards for monitoring ( J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61[10 suppl]:E1496). "If we eliminate unnecessary monitoring, it should result in a reduction in the overall alarm burden," Dr. Funk said. A new practice alert from the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses outlines evidence-based protocols to reduce false or non-actionable alarms and improve the effective use of these monitoring aids. Clinical alarms designed to alert nurses to changes in their patients conditions have become a continual barrage of noise that poses a significant threat to patient safety, the AACN stated. Since 1983, the average number of alarms in an ICU has increased from six to 40, despite the fact that humans have difficulty learning more than six different alarm sounds, according to the AACN. The sensory overload from sounds emitted by monitors, infusion pumps, ventilators and other devices can cause a person to become desensitized to the alarms. Such alarm fatigue may result in delayed responses or missed alarms, sometimes contributing to patient deaths. Based on the latest available evidence, the AACN practice alert summarizes expected nursing practice related to alarm management, including:

Provide proper skin preparation for ECG electrodes, which can improve conductivity and decrease the number of false alarms; Change ECG electrodes daily; Customize alarm parameters and levels on ECG monitors; Customize delay settings and threshold settings on oxygen saturation via puls e oximetry monitors. The combination of appropriate alarm delays and threshold settings optimizes the monitor to its highest potential, producing an alarm when action is required; Provide initial and ongoing education about devices with alarms; Establish interprofessional teams to address issues related to alarms, such as the development of policies and procedures; Monitor only those patients with clinical indications for monitoring. This alert is the latest in a series of guidelines issued by AACN to standardize practice and update nurses and other healthcare providers on new healthcare advances and trends. Additional alerts address ventilator associated pneumonia, pulmonary artery pressure monitoring, dysrhythmia monitoring, ST segment monitoring, family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures and verification of feeding-tube placement. Reference: http://news.nurse.com

Reaction:

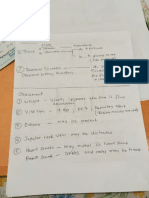

As a student, I learned that most of the devices in the ICU did have programmable settings/limits that the RN could adjust per patient and would reduce the number of useless alarms. For some reason, the RN's rarely adjusted these parameters. I got excellent tele experience during my time there; the experienced RN's would often send me to assess the alarm, and report my perceived level of severity. They did not utilize the alarm parameters, but did utilize the phenomenon as an incredible teaching opportunity. Of course I meant overwhelmed; not overwhelmed but the message is still the same. Basically, the same argument could be said of hand washing. Nurses who claim that they are overwhelmed and fatigued by the numbers of alarms that go off during their shifts could also say that they cannot possibly keep up with washing their hands every time they should wash their hands because they have hand washing fatigue. We absolutely do need to get alarms and things that beep down to the necessary ones only (e.g. as mentioned in the article, the person's pulse does not need to audibly beep when on a cardiac monitor or oximeter) but nurses need to be very careful about using excuses for such actions as ignoring alarms. The main question that needs to be explored is this: How much of the problem is alarm fatigue and how much of it is alarm ignorance? How many alarms are simply ignored by nurses as opposed to those nurses being overwhelmed by a constant barrage of alarms? This is a great thing to see happen. I have been chastised and told I had questionable judgement for practicing what I called senseless noise control in clinical situations most would expect to be more enlightened and open to quality improvement. I have found the most useful idea to keep in mind and use to teach is that of: "Treat the patient, not the monitor". IRENE ANN L. PEROCHO

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Nursing Care Plans For Burned PatientDocument5 pagesNursing Care Plans For Burned PatientJunah Marie Rubinos Palarca85% (26)

- Report EcgDocument144 pagesReport EcgPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument9 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Sergei Vasilievich RachmaninoffDocument2 pagesSergei Vasilievich RachmaninoffPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Causes of IdwDocument1 pageCauses of IdwPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Or ChecklistDocument2 pagesOr ChecklistPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- AbortionDocument77 pagesAbortionPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- AbortionDocument77 pagesAbortionPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Grade Ii - B S. Y. 2013 - 2014Document2 pagesGrade Ii - B S. Y. 2013 - 2014Peace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Review medications, nursing roles, UPH missionDocument2 pagesReview medications, nursing roles, UPH missionPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- University of Perpetual Help SystemDocument2 pagesUniversity of Perpetual Help SystemPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Review medications, nursing roles, UPH missionDocument2 pagesReview medications, nursing roles, UPH missionPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Nursing StaffingDocument5 pagesNursing StaffingPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Bone TumorsDocument22 pagesBone TumorsPeace Andong Perocho100% (1)

- Relit For Ate JulieDocument10 pagesRelit For Ate JuliePeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Angina Pectoris SharinaDocument3 pagesAngina Pectoris SharinaPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Patho ShoDocument1 pagePatho ShoPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- DrugDocument3 pagesDrugPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- BiogesicDocument2 pagesBiogesicianecunarNo ratings yet

- Reaction JournalDocument2 pagesReaction JournalPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- RubelinDocument7 pagesRubelinPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and The House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument9 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and The House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Potse MindDocument1 pagePotse MindPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Chancroid TocDocument12 pagesChancroid TocPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- To Control Nausea and Vomiting: Drug StudyDocument2 pagesTo Control Nausea and Vomiting: Drug StudyPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- ChancroidDocument2 pagesChancroidPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- DrugsDocument2 pagesDrugsPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Herpes ZosterDocument3 pagesHerpes ZosterPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- DrugsDocument2 pagesDrugsPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Article Reaction Sa C.A. 2Document8 pagesArticle Reaction Sa C.A. 2Peace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Complete Drugs StudyDocument13 pagesComplete Drugs StudyPeace Andong PerochoNo ratings yet

- Pulse OximetryDocument29 pagesPulse OximetryAnton ScheepersNo ratings yet

- SurgiVet Advisor Tech Vital Signs MonitorDocument6 pagesSurgiVet Advisor Tech Vital Signs MonitorKihanNo ratings yet

- Mark Keterangan: Acuan Perencanaan Alat Kesehatan Kode Rs 1603085 Form f3Document8 pagesMark Keterangan: Acuan Perencanaan Alat Kesehatan Kode Rs 1603085 Form f3Aandi IhramNo ratings yet

- Meas Emitter Assembly Elm-4000 Series: Spo Optical Sensor ComponentDocument4 pagesMeas Emitter Assembly Elm-4000 Series: Spo Optical Sensor Componentmaria jose rodriguez lopezNo ratings yet

- Oximeter: Handheld PulseDocument4 pagesOximeter: Handheld PulseTopan AssyNo ratings yet

- Massimo - Radical 7 (Operation Manual)Document49 pagesMassimo - Radical 7 (Operation Manual)Dodik E. PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Cardiac Surgery - General Principles - UpToDateDocument58 pagesAnesthesia For Cardiac Surgery - General Principles - UpToDateEvoluciones MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Arterial Blood Gases - UpToDateDocument41 pagesArterial Blood Gases - UpToDateMelanny Perez GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Output Stroke Volume Preload AfterloadDocument14 pagesCardiac Output Stroke Volume Preload AfterloadAria RiversNo ratings yet

- Dash ™ 3000/4000/5000 Patient Monitor: Service ManualDocument8 pagesDash ™ 3000/4000/5000 Patient Monitor: Service ManualSERGIO PEREZNo ratings yet

- Newborn Pulmonary Hypertension Causes and TreatmentDocument10 pagesNewborn Pulmonary Hypertension Causes and TreatmentWali MoralesNo ratings yet

- HEYER VizOR 6 - Manual 1.0 EN PDFDocument128 pagesHEYER VizOR 6 - Manual 1.0 EN PDFkalandorka92No ratings yet

- Oxygen Saturation Index Predicts Severity of Respiratory FailureDocument7 pagesOxygen Saturation Index Predicts Severity of Respiratory FailureKaren MVNo ratings yet

- Mir Spirobank Ii User ManualDocument37 pagesMir Spirobank Ii User ManualNurul FathiaNo ratings yet

- GE Health Care - Individual Moduls Technical MaualDocument622 pagesGE Health Care - Individual Moduls Technical MaualmaruthaiNo ratings yet

- Ruppels Manual of Pulmonary Function Testing 10th Edition Mottram Test BankDocument13 pagesRuppels Manual of Pulmonary Function Testing 10th Edition Mottram Test Bankkhuyentryphenakj1100% (29)

- Digital Technology in EndoDocument91 pagesDigital Technology in Endonandani kumariNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan for Patient SafetyDocument9 pagesNursing Care Plan for Patient SafetyACOB, Jamil C.No ratings yet

- Wearable Sensors and Systems1Document23 pagesWearable Sensors and Systems1ArulkarthickNo ratings yet

- Pulse OximetryDocument2 pagesPulse OximetryBarish KhandakerNo ratings yet

- FORE-SIGHT - Direct Accuracy Performance Comparison of Cerebral Oximeter Devices PDFDocument4 pagesFORE-SIGHT - Direct Accuracy Performance Comparison of Cerebral Oximeter Devices PDFRaluca LNo ratings yet

- Pulse Oxymeter FixDocument7 pagesPulse Oxymeter FixNaufal AlbabNo ratings yet

- Criticare Ncompass 8100H Service ManualDocument142 pagesCriticare Ncompass 8100H Service Manualadin othmanNo ratings yet

- Nellcor pm10n PDFDocument112 pagesNellcor pm10n PDFFùq Tất ỨqNo ratings yet

- Philips Intellivue Patient Monitors PDFDocument20 pagesPhilips Intellivue Patient Monitors PDFbprzNo ratings yet

- IndexDocument51 pagesIndexAaron McAlisterNo ratings yet

- Nicu ReportDocument18 pagesNicu ReportKabita KarakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 29: Nursing Management: Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases Test BankDocument15 pagesChapter 29: Nursing Management: Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases Test BankBriseidaSolisNo ratings yet

- Pulse Oximetry: Understanding Its Basic Principles Facilitates Appreciation of Its LimitationsDocument11 pagesPulse Oximetry: Understanding Its Basic Principles Facilitates Appreciation of Its LimitationsParadox PraveenNo ratings yet