Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2013 14977 010

Uploaded by

Catarina C.Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2013 14977 010

Uploaded by

Catarina C.Copyright:

Available Formats

Health Psychology 2013, Vol. 32, No.

5, 561570

2013 American Psychological Association 0278-6133/13/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029887

When Risk Communication Backfires: Randomized Controlled Trial on Self-Affirmation and Reactance to Personalized Risk Feedback in High-Risk Individuals

Natalie Schz and Benjamin Schz

University of Tasmania

Michael Eid

Freie Universitt Berlin

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Objective: Health promotion often faces the problem that populations with high behavioral risk profiles respond defensively to health promotion messages by negating risk or reactant behavior. Self-affirmation theory proposes that defensive reactions are an attempt of the self-system to maintain integrity. In this article, we examine whether a self-affirmation manipulation can mitigate defensive responses to personalized visual risk feedback in the skin cancer prevention context (ultraviolet [UV] photography), and whether the effects pertain to individuals with high behavioral risk status (high personal relevance of tanning). Method: We conducted a full-factorial randomized controlled trial (N 292; age 1171) following a 2 2 design (UV photo yes/no, self-affirmation yes/no). Follow-up period was 2 weeks. Subsequent tanning behavior, sun avoidance intentions, and risk perception. Results: A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed a three-way interaction between risk feedback, the self-affirmation manipulation, and risk status for the three outcome measures. Follow-up analyses of variance (ANOVAs) indicated that high-risk individuals receiving only the risk feedback intervention reacted defensively and reported higher exposure. A self-affirmation manipulation mitigates this reactance effect both on the level of cognitions and behavior. Conclusion: Self-affirmation has influential implications not only for Social Psychology but also for health prevention measures. The findings support the effectiveness of self-affirmation in reducing reactant and defensive reactions to personalized visual risk feedback. Interactions with health risk status indicate that self-affirmation might increase the effectiveness of health promotion messages in high-risk populations. Keywords: self-affirmation, reactance, sun protection, skin cancer, UV photography

Dont wanna be taught to be no fool (Ramones, 1980, track 10). This quote nicely illustrates a core problem in health promotion: People do not want to be told they behave in foolish or unhealthy ways, because very often they know, and they may have good subjective reasons for this. Accordingly, a meta-analysis revealed that those with the highest need for behavioral health promotion programs (i.e., those with the highest risk) are also the most likely to drop out of such programs, or do not even enroll (Noguchi, Albarracn, Durantini, & Glasman, 2007).

This article tests whether an application of self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988) can be useful in mitigating such reactant or defensive behavior patterns in a low-threshold health promotion context: personalized risk feedback on skin cancer risk using ultraviolet (UV) photographs.

Reactance and Defensive Responses in Health Promotion

Reactance is a problem at the core of health promotion research (Crossley, 2002). There is, however, surprisingly little systematic research on reactance and on ways to overcome it. It has been discussed whether the tendency to be reactant is a trait-like characteristic (Brehm & Brehm, 1981; Crossley, 2002) or a reaction to the behavioral demands in health promotion messages (Albarracn, Durantini, Earl, Gunnoe, & Leeper, 2008). Stage theories of health behavior assume that the tendency to react defensively is a maladaptive outcome of deliberation processes. For example, according to the Precaution Adoption Process Model (Weinstein & Sandman, 1992), individuals who have decided not to act, are much harder to convince about the benefits of healthy behavior because they have formed a negative opinion about it. Correspondingly, the authors assume that individuals decided not to act are more likely to react defensively or reactant when confronted with personalized risk feedback.

561

Natalie Schz, Centre of Research Excellence for Chronic Respiratory Disease, School of Medicine, University of Tasmania, Tasmania, Australia; Benjamin Schz, School of Psychology, University of Tasmania; Michael Eid, Department of Education and Psychology, Methods and Evaluation, Freie Universitt Berlin, Berlin, Germany. During the work on her dissertation, the first author was a pre-doctoral fellow of the International Max Planck Research School The Life Course: Evolutionary and Ontogenetic Dynamics (LIFE, www.imprs-life .mpg.de). We thank Linda Brust, Lena Fleig, Jette Hunold, Marie Nixdorf, Jana Richert, and Carola Scholz for their assistance during data collection. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Natalie Schz, Centre of Research Excellence for Chronic Respiratory Disease, School of Medicine, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 23, Hobart TAS 7001, Australia. E-mail: natalie.schuez@utas.edu.au

562

SCHZ, SCHZ, AND EID

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

This might partly be because of the fact that people prefer congenial to uncongenial information that is in discordance with their attitude or behavior (Hart et al., 2009). Receiving uncongenial information often leads to defensive reactions such as doubting the quality of the arguments (e.g., Edwards & Smith, 1996). This bias is particularly pronounced in risk feedback situations (Jemmott, Ditto, & Croyle, 1986). Therefore, individuals who engage in a specific (risk) behavior because of personal goals (such as tanning to look better) are especially prone to defensively process information that challenges the validity and the pursuit of these goals (e.g., information on skin cancer risk factors). The challenge for health promotion lies in the fact that defensive or reactant tendencies are much more likely in individuals at higher risk for the very health problem a measure tries to target (Noguchi et al., 2007). The question is how health promotion can reach these underserved and at-risk populations without evoking defensive or reactant behaviors such as an increase in risk behavior or risk-favoring cognitions (boomerang effect; Brehm & Brehm, 1981). Are they really hopeless cases?

Self-Affirmation and Defensive Responses: A Function of Personal Relevance

Self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988) could be a useful tool for understanding and modifying such defensive responses. Selfaffirmation theory is rooted in social and personality psychology with first applications mainly in attitude research (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). However, the theory can also be usefully applied to the exploration and modification of defensive reactions in the health domain, as a review paper by Harris and Epton (2009) demonstrates. Self-affirmation theory states that individuals react defensively to threatening information because they strive for self-integrity and a sense of coherence. Messages about personal risk are threatening, because they jeopardize ones sense of selfintegrity being reminded that one engages in unwise or unhealthy behavior does not go along very well with thinking of oneself as a coherent person (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). Accordingly, the motive for defensive reactions is maintaining a positive view of the self. However, self-affirmation theory also postulates that such defensive reactions are less likely if the individual is given the chance to affirm another important domain of the selfsystem unrelated to health, such as personal values, central beliefs or relationships. This reduces the need to process threatening information defensively, as the integrity of the system is ensured by the affirmed alternative domain (Sherman & Cohen, 2006). Interestingly enough, these effects are not mediated by global self-esteem ratings, and it has been suggested that the effects of self-affirmation are stronger when specific domains of the selfsystem are affirmed than when the system as a whole is affirmed (McQueen & Klein, 2006). Effects of self-affirmation on reducing defensive reactions have been found in many domains from challenging political beliefs (Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, 2000) to health behaviors (for an overview, see Harris & Epton, 2009). According to theory, the effects of self-affirmation should be particularly pronounced in individuals in whom discordant information targets essential concepts of the self-system such as longterm lifestyles or personal goals. This has also been shown in the health domain: While low-risk individuals might profit from selfaffirmation by being able to assess the personal relevance of a

health threat more objectively, individuals with higher risk status seem to profit in terms of adaptive adjustments of risk perception and cognitions related to health behavior change (e.g., Griffin & Harris, 2011; Harris & Napper, 2005). However, there is also evidence that individuals with a very high risk status might not benefit as much as medium-high risk individuals (Klein & Harris, 2009). Risk status so far has been indicated by risk behavior such as consumption of tuna containing high levels of mercury (Griffin & Harris, 2011) or alcohol consumption (Harris & Napper, 2005). However, self-affirmation theory assumes that the level of threat discordant information poses to the self-system also depends on the importance of the threatened domain. Our study adds to previous research in that our conceptualization of risk status directly assesses the subjective importance of the risk behavior, namely via appearance reasons for tanning (Jones & Leary, 1994), validated against actual risk behavior. This corresponds to the theoretical assumptions that subjectively important domains of the self-system are more prone to be protected by defensive reactions. The effects of self-affirmation on accepting universal risk information such as general health messages (Epton & Harris, 2008), fictitious medical articles (van Koningsbruggen, Das, & RoskosEwoldsen, 2009), or threatening images (Harris, Mayle, Mabbott, & Napper, 2007) are well documented. Our study goes beyond this by testing whether self-affirmation is useful in reducing reactance and defensive reactions after personalized risk feedback, where threats to the self are particularly strong.

Personalized Risk Feedback

Personalized or individualized risk feedback (i.e., after a screening, receiving a message about ones personal risk for a disease) is very likely to produce defensive reactions (Jemmot et al., 1986). We examine personalized visual risk feedback in the skin cancer prevention context. This context is particularly interesting, because there are validated procedures for personalized visual risk feedback (e.g., Gibbons, Gerrard, Lane, Mahler, & Kulik, 2005; Mahler, Kulik, Gibbons, Gerrard, & Harrell, 2003). Furthermore, there is evidence for reactant behaviors and cognitions following personalized visual risk feedback in high-risk groups, but so far there have been no attempts on how to overcome this (Jones & Leary, 1994; Mahler, Kulik, Gerrard, & Gibbons, 2007). In the skin cancer prevention context, visual risk feedback is often given by UV photography. Photos taken with UV lightemitting lamps highlight skin cells damaged by overexposure to the sun (Taylor, Stern, Leyden & Gilchrest, 1990): The photodamaged hyperpigmented areas of the skin absorb the UV light emitted by the UV lamp. These damaged areas appear as dark spots on the photos and are indicative of premature skin aging and higher risks of skin cancer. Some studies found UV photos to be effective in changing sun protection intentions (Mahler et al., 2003) and tanning booth use (Gibbons et al., 2005). However, the overall evidence is somewhat inconclusive (Hollands, Hankins, & Marteau, 2010). Other studies demonstrated that personalized visual UV risk feedback can backfire; individuals receiving UV photos were reactant in that they spent more hours in the sun than control group participants (Mahler et al., 2007). One possible reason for this is that there are individuals who consider tans attractive and accordingly are less likely to protect

SELF-AFFIRMATION AND PERSONALIZED RISK FEEDBACK

563

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

themselves from the sun (Garside, Pearson & Moxham, 2010). It is assumed that general appearance concerns lie behind such backfiring effects (Jones & Leary, 1994). Furthermore, research has suggested that suntanning could be interpreted as an attempt to defend self-esteem by conforming to perceived norms such as the attractiveness of tanned skin (Cox et al., 2009). Self-affirmation theory provides a theoretical background to understand and modify such reactions: Receiving personalized visual risk feedback via UV photos might challenge the selfintegrity of individuals with high appearance concerns, as it suggests that one of their important values (tanning to look attractive) is doing actual harm to their appearance (premature wrinkles and age spots) and their health (skin cancer). The boomerang effect that was shown for personalized (Mahler et al., 2007) and appearance-based (Jones & Leary, 1994) feedback supports this idea and suggests that skin cancer prevention constitutes a suitable background before which to study reactant behaviors following personalized risk feedback.

Aims and Hypotheses

As a consequence, our study aims at showing that allowing high-risk individuals who perceive tans as highly attractive to affirm their self-system before receiving personalized visual UV photo risk feedback should reduce reactant or defensive cognitions and behaviors. There so far is only sparse evidence that selfaffirmation may also promote longer-term behavior changes (Epton & Harris, 2008), and this study aims at testing the effects of self-affirmation on risk behavior in high-risk individuals. More specifically, we tested the following hypotheses: 1. As self-affirmation in combination with risk information has been shown to decrease defensive processing of risk information especially in high-risk individuals (e.g., Harris & Napper, 2005), we expect that high-risk individuals receiving both, the selfaffirmation manipulation and personalized risk feedback will show adaptive changes in risk perception and sun avoidance intentions and lower rates of risk behavior compared with high-risk individuals receiving the personalized risk feedback only. 2. The combination of self-affirmation and risk feedback will be more efficient in effecting adaptive changes in cognitions and behavior in high-risk individuals than in low-risk individuals. Overall, the hypotheses should be reflected in a three-way interaction of risk status personalized risk feedback selfaffirmation: high-risk individuals receiving the self-affirmation manipulation in addition to the risk feedback intervention should profit most in terms of changes in cognitions and behavior.

chart. Sample size was determined based on a medium-sized interaction effect of f 0.25 with .05 and power .80 using the pwr-package in R (Champely, 2009), resulting in a required minimum of 45 participants per group. Because previous studies in comparable settings suggested attrition rates of up to 50% (Schz, Wiedemann, Mallach, & Scholz, 2009), we aimed for a total sample size of 270 participants. The final sample consisted of 266 persons, of which 30.6% were male participants. Age ranged between 11 and 71 years (M 33.78). Visitors were informed about UV photography and the study in a brochure. Upon entering the lab set up at the science event, participants were asked to fill in the baseline questionnaire and an informed consent form, which also informed about the Web-based follow-up assessment and asked for e-mail addresses for this purpose. Eligibility criteria were sufficient knowledge of the German language. Parents or guardians provided informed consent for underage participants. Leaflets with sun protection guidelines (Skin Cancer Foundation, 2008) were distributed. At the end of the baseline questionnaire, according to random order, the self-affirmation or control task (see below) was attached. After filling in the questionnaire, every participants face was photographed and either processed to show UV damage (see below) or not, also according to the randomized schedule. Pictures were printed and handed to participants. Participants receiving an unprocessed photo could download their processed UV picture after finishing the follow-up questionnaire. As baseline assessment took place during a science event, participants were informed that they would be allocated to different groups of a scientific experiment, but without mentioning the characteristics of the experimental and control conditions. Experimenters were blind with regard to the self-affirmation condition. A few participants did not pick up their UV photo because they did not want to wait for them to be printed. These were removed from the analyses (Figure 1). Follow-up measures were assessed online 2 weeks after baseline. The same measures were assessed at baseline and at followup, the only difference being the stem of the behavioral items, which asked for exposure behavior during the summer (baseline) or during the past 2 weeks (follow-up).

Personalized Visual Risk Feedback

UV photos were taken with a regular SLR camera and two external flashes with UV emission filters (for full apparatus setup, see Fabrizi, Pagliarello, & Massi, 2008). UV photos for the personalized risk feedback group were processed in an Adobe Photoshop filter routine. Red color components were reduced, and blue components were increased to improve clarity and interpretability of sun-damaged areas. Photos for the control group were not processed, thus showing a normal photo of the face.

Method Participants and Procedure

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted during a public science event at a German university in the summer of 2009. The RCT with two points of measurement 2 weeks apart followed a 2 2 (UV photograph yes/no self-affirmation yes/no) factorial design. Participants were allocated to conditions using a computer-generated randomized list for 300 participants with 75 participants in every experimental group (Research Randomizer; Urbaniak & Plous, 2009). Figure 1 shows the participant flow-

Self-Affirmation Manipulation

Self-affirmation was manipulated using a validated procedure (Napper, Harris, & Epton, 2009) by asking participants in the affirmation conditions (SA, UVSA) to rate themselves on a 5-point scale presenting a range of personal strengths and values (e.g., I value my ability to think critically, 1 very much like me to 5 very much unlike me). Filling in this scale

564

SCHZ, SCHZ, AND EID

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Figure 1. Participant flow chart.

is assumed to help participants focusing on values important to their self-image, which in turn gives them the chance to reaffirm themselves. Participants in the nonaffirmation conditions (C and UV) rated a celebrity on the same scale (German celebrity Dieter Bohlen, a former pop singer and current juror on TV casting shows; original manipulation: David Beckham). This procedure ensures that the affirmation and nonaffirmation conditions are as identical as possible. Participants filled out the value scale before they were being photographed, thereby being self-affirmed before receiving the risk feedback.

Outcomes and Measures

The same measures were assessed at baseline and at follow-up: the only difference being the stem of the behavioral items, which asked for exposure behavior during the summer (baseline) and during the past 2 weeks (follow-up). Intercorrelations and psychometric properties of all measures at baseline and follow-up can be obtained from the first author. Confirmatory factor analyses verified the unidimensionality of the scales, and mean scores were computed for all scales. Exposure behavior. The primary behavioral outcome, deliberate sun exposure was assessed with two items (Eid, 1997; Cronbachs alpha T1/T2 .80/.84). On a Likert scale from 1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree, participants indicated whether they tried to get a tan and deliberately exposed themselves

to the sun. The stem When the sun was shining during this summer . . . (baseline) was followed by the items I tried to get as tanned as possible, and I often went outside to get a tan. Behavior at follow-up was assessed with the stem When the sun was shining during the past 2 weeks . . . and the same two items. Sun avoidance intentions. Intention was assessed according to Ajzen (2006; Cronbachs alpha T1/T2 .79/.75) with three items on a 7-point Likert scale, for example, I intend to avoid the midday sun: 1 do not intend at all to 7 strongly intend. Risk perception. Risk perception was measured as described in Schwarzer (2008) and adapted to sun protection and skin cancer/ skin aging. Two items asked for comparative risk perception with regard to skin cancer and premature skin aging: Compared to a person of my age and gender, my own risk of getting skin cancer is and Compared to a person of my age and gender, my own risk for premature skin aging is: 1 very low to 5 very high. Cronbachs alpha at T1/T2 was .69/.72. Risk status. Subjective importance of tanning (risk behavior) as an indicator of risk status was assessed with three items (Cronbachs alpha T1/T2 .74/.76) asking for the importance of appearance and health reasons for tanning: I feel more attractive when Im tanned, My skin looks better when tanned, and I try to abstain from tanning in order to keep my good health (reversecoded). Answers were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree.

SELF-AFFIRMATION AND PERSONALIZED RISK FEEDBACK

565

Statistical Analyses

To test for the expected three-way interaction between the two interventions and risk status measured at baseline, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted. The outcomes (risk perception, intention, and behavior) were measured both at baseline and at follow-up. Baseline scores of the measures were included in the analyses as covariates. To test for the specific effects on each of the outcomes, follow-up analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted. All analyses were performed in R (R Development Core Team, 2010).

Results

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Dropout Analyses

There was no differential attrition across experimental groups, Cramers V .16, p .06. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed that, overall, there were no pretest differences between retained and dropped-out participants on any of the study variables, Pillais Trace 0.01, F(4, 253) 0.87, p .48, Cohens f 0.1. In the two UV photo conditions, there were several people who did not pick up their photograph (Figure 1). However, there were neither any baseline difference between those not picking up their photograph and the other study participants, Pillais Trace 0.03, F(4, 279) 1.96, p .10, Cohens f 0.17, nor were there differences on any of the study variables at follow-up, Pillais Trace 0.03, F(4, 151) 1.12, p .35, Cohens f 0.17.

Randomization Checks

Participants in the four experimental groups did not differ with regard to age, ANOVA: F(3, 154) 0.27, p .85, Cohens f 0.07; gender, 2 test: 2 (3) 3.93, p .27; or skin type, ANOVA: F(3, 256) 0.17, p .92, Cohens f 0.04. Furthermore, there were no significant between-groups differences on baseline scores of the study variables: MANOVA: Pillais Trace 0.04, F(3, 254) 0.83, p .62, Cohens f 0.10.1

Risk Status Validation

Higher subjective importance of tanning at baseline was associated with higher deliberate exposure behavior, r(283) .57, p .001; lower intentions to avoid sun overexposure, r(285) .69, p .001; and higher risk perception, r(286) .22, p .001, at baseline. This indicates that appearance and health reasons for tanning are validly assessing individuals with higher behavioral risk for skin cancer and premature skin aging. Overall, there was a significant decrease in risk status between baseline and followup, t(158) 3.17, p .002, Cohens d 0.37. However, there neither was a main effect nor an interaction effect between the two interventions on risk status difference scores.

Risk Status, Personalized Visual Risk Feedback, and Self-Affirmation Interactions

To test for the proposed hypotheses, participants were assigned a high risk status if they scored above 3 on the risk status scale; participants scoring up to 3 were allocated to the low risk group. A MANCOVA revealed significant main effects of both experi-

mental manipulations on the outcome measures (main effect of personalized risk feedback: Pillais Trace 0.09, F(1, 144) 4.71, p .004, Cohens f 0.15; main effect of self-affirmation manipulation: Pillais Trace 0.06, F(1, 144) 2.89, p .04, Cohens f 0.14), as well as a significant self-affirmation risk status interaction: Pillais Trace 0.08, F(1, 144) 4.17, p .01, Cohens f 0.17. Furthermore, there was a three-way interaction effect between the two interventions and risk status on the three outcome measures, Pillais Trace 0.07, F(1, 144) 3.53, p .02, Cohens f 0.14. Because the global interaction effect turned out to be significant, follow-up ANCOVAs were conducted for each of the three outcomes. Exposure behavior. There was a significant main effect of the self-affirmation manipulation on risk behavior: self-affirmed participants reported lower rates of deliberate sun exposure than nonaffirmed participants, F(1, 152) 4.17, p .04, Cohens d 0.25. In addition, there was a significant self-affirmation risk status interaction on risk behavior, F(1, 152) 6.02, p .02, Cohens f 0.20, high-risk participants reported higher adaptive changes in behavior after receiving the self-affirmation manipulation when compared with high-risk participants who did not get the chance to self-affirm, whereas low-risk participants in the affirmation and nonaffirmation conditions did not differ (Figure 2a). More important, there was a significant three-way interaction between the two experimental manipulations and risk status, F(1, 152) 6.87, p .01, Cohens f 0.21: As can be seen in Figure 2b, high-risk individuals receiving only the UV photo showed reactant behavior in reporting higher levels of deliberate sun exposure than high-risk individuals who were self-affirmed before viewing the UV photo, t(152) 2.67, p .004, Cohens d 0.66, while there is no significant difference between the experimental groups in low-risk individuals. Sun avoidance intentions. There also was a significant threeway interaction of the experimental conditions and risk status on intentions to avoid excessive sun exposure, F(1, 153) 5.81, p .02, Cohens f 0.20. Even though high-risk participants receiving both intervention components reported a higher increase in avoidance intentions than high-risk participants receiving the risk feedback only, this difference was not significant, t(153) 0.72, p .24, Cohens d 0.16. Apart from the three-way interaction, there was a significant main effect of the risk feedback intervention on avoidance intentions; overall, participants receiving a UV photo reported higher increases in intentions than participants receiving no risk feedback, F(1, 153) 3.94, p .048, Cohens d 0.18. There were no other main or interaction effects of the experimental manipulations on sun avoidance intentions. Risk perception. As was the case with exposure behavior, there was a significant self-affirmation risk status interaction effect on risk perception, F(1, 153) 4.69, p .03, Cohens f 0.18. High-risk participants not given the chance to self-affirm reported an overall decrease in risk perception, whereas high-risk participants in the self-affirmation condition reported a slight increase. However, this difference was not significant, t(153) 0.18, p .43, Cohens d 0.06. It seems as if the significant interaction effect is because of differences between low-risk participants being self-affirmed and

1 Tables with baseline demographic characteristics split per group are available from the first author upon request.

566

SCHZ, SCHZ, AND EID

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Figure 2. Interaction plots depicting (a) exposure behavior (1 strongly disagree, 4 strongly agree) for participants with a high vs. low risk status in the self-affirmation and non-affirmation condition, (b) exposure behavior for participants with a high vs. low risk status in the four experimental groups, (c) sun avoidance intentions (1 do not intent at all, 7 strongly intend) for participants in the four experimental groups, (d) risk perception (1 very low risk, 5 very high risk) for participants with a high vs. low risk status in the self-affirmation and non-affirmation condition. The y-axis presents the original scale of each outcome.

low-risk participants receiving no self-affirmation: t(157) 3.54, p .001, Cohens d 0.49 (Figure 2d).

Discussion

In this study, we examined whether a self-affirmation manipulation affected the impact of personalized visual risk feedback (UV photographs) on social cognitions and behavior, with a particular focus on reactant or defensive behavior in high-risk individuals with high appearance reasons for tanning. We found that individuals with high appearance reasons for tanning reported higher rates of sun exposure after receiving the

personalized risk feedback. In contrast, individuals with high appearance reasons, who were self-affirmed in addition to receiving risk feedback, decreased deliberate tanning. This study was the first to show that the effects of personalized visual risk feedback on reactant behavior can be buffered by self-affirmation and among the first to test the impact of such interventions on risk behavior at follow-up.

Personalized Risk Feedback and Reactance

The study replicated findings from previous studies showing a beneficial effect of UV photos on subsequent sun protection in-

SELF-AFFIRMATION AND PERSONALIZED RISK FEEDBACK

567

tentions (e.g., Mahler et al., 2007; Mahler et al., 2003). With regard to actual behavior, however, interventions employing such personalized or appearance-based feedback (Jones & Leary, 1994; Mahler et al., 2007) also showed that these manipulations may backfire and result in higher rates of subsequent risk behavior. A similar effect has also become evident in other domains such as HIV prevention: a meta-analysis showed that fear appeals led to higher risk perceptions, but also to more risk behavior (Earl & Albarracn, 2007). This suggests that particularly individuals at high risk could show reactance after receiving risk feedback, even though they might admit that they are more at risk by reporting higher risk perceptions or higher protection intentions.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Personalized Risk Feedback and Self-affirmation in High- and Low-Risk Individuals

According to self-affirmation theory (Steele, 1988), such defensive processing is an attempt of the self-system to maintain a sense of integrity (being a healthy and attractive person) despite threatening information (personalized visual risk feedback showing skin lesions with high risk for premature skin aging and skin cancer development). Self-affirmation theory also proposes that affirming other domains of the self-system should meet the need to maintain a sense of integrity and thus reduce the need to defensively process the personalized risk feedback. Our results confirm these basic tenets by showing that defensive reactions to self-system threats also translate into actual reactant behavior, and that the affirmation of alternative domains of the self-system can ameliorate these reactions. The results can also be interpreted before the background of research by Cox et al. (2009) who suggested that sun tanning could be an attempt to conform to perceived social normsaffirmed participants in our study might have felt less threatened by the consequences of not conforming to the social norm of tan-related attractiveness. The most significant results with regard to reactance reduction emerged for sun exposure behavior: Individuals high at risk receiving only a UV photo increased their tanning, whereas individuals high at risk who also received the self-affirmation manipulation decreased their tanning. This indicates that detrimental reactant behavior patterns can be ameliorated by giving individuals the chance to self-affirm. A similar trend was discovered for intentions to avoid sun overexposure. According to selfaffirmation theory, such effects are highly plausible (Sherman, Nelson, & Steele, 2000): For individuals deliberately engaging in risk behavior, risk information (especially if in personalized visual form giving direct tangible feedback on facial skin lesions) threatens an integral part of the self-system, resulting in a higher need for maintenance of self-integrity and accordingly stronger defensive processing on a cognitive and behavioral level. In contrast to the effects of self-affirmation for individuals with high appearance norms and higher behavioral risk, the effects of self-affirmation on low-risk individuals pointed in the other direction. Upon being self-affirmed, low-risk individuals reported lower scores in risk perception. Likewise, self-affirmed low-risk participants receiving the risk feedback reported lower protection intentions than those who did not self-affirm. These results corroborate findings from a recent study by Griffin and Harris (2011), which showed that self-affirmation may not only reduce defensiveness in high-risk individuals but also enables low-risk individuals to as-

sess the personal relevance of a health threat more objectively. This means that the negative effects of self-affirmation on intentions and risk perception in low-risk individuals might have been the result of an adaptive process in which low-risk individuals in the self-affirmation condition have reassessed their own risk for skin cancer and premature skin aging and have come to the correct conclusionthat they are not particularly at risk. Nevertheless, one has to bear in mind that self-affirmation may indeed have detrimental effects for low-risk individuals: A study by Harris and Napper (2005) found that self-affirmation in low-risk individuals may also decrease risk perceptions regarding diseases not targeted in a health message. In a similar vein, van Koningsbruggen and Das (2009) showed that self-affirmation can go along with decreases in health behavior intentions in low-risk individuals. They argue that risk messages are not threatening to low-risk individuals; thereby, self-affirmation might decrease information processing, which may result in less favorable attitudes (Brinol, Petty, Gallardo, & DeMarree, 2007). Our study corroborates previous research on self-affirmation and sun protection behavior (Jessop, Simmonds, & Sparks, 2009) and adds to the literature that self-affirmation can ameliorate the defensive or reactant cognitive and behavioral responses that have been found in research on personalized visual risk feedback in skin cancer prevention (Jones & Leary, 1994; Mahler et al., 2007).

Implications

Our study has some important practical implications: Individuals who deliberately engage in health risk behaviors are at the highest risk for the respective health problems, but at the same time often are least persuaded by health promotion messages and most likely to engage in reactant behaviors (Albarracn et al., 2008). Such individuals with important subjective reasons for risk behaviors are a pivotal target group for health behavior interventions that is particularly hard to tackle (Jemmott et al., 1986; Sherman et al., 2000). Our study corroborates previous research on the effects of self-affirmation for high-risk individuals (e.g., Harris & Napper, 2005), but extends these differential findings according to risk status to actual risk behavior in a behavioral domain particularly susceptible to reactance, namely skin cancer prevention. Our results suggest that a combination of personal risk feedback and self-affirmation can result in reduction of reactance and beneficial behavior change in high-risk individuals. There are also implications resulting from our operationalization of risk status. Rather than examining levels of risk behavior as indicators of risk status, we used the subjective importance of risk behavior. This is in accordance with self-affirmation theory, which considers subjectively important domains of the self-system as particularly vulnerable to defensive reactions. Furthermore, in the context of sun protection behavior, external factors such as weather conditions play a fundamental role. Because no sun protection is needed when the UV index is very low, behavioral measures not necessarily provide a valid assessment of risk status. Thus, an attitudinal measure might more validly assess risk status in this case. At this point, it is worthwhile to mention that the selfaffirmation manipulation based on Napper, Harris, and Epton (2009) consists of a short and economic value scale, and not of a time-consuming task such as writing an essay. This suggests that

568

SCHZ, SCHZ, AND EID

such self-affirmation manipulations are a very economical, yet effective means to reduce defensive processing in high-risk individuals. Nevertheless, further research on reactance to health promotion messages is called for. It is entirely possible that because of a publication bias toward effective health behavior change interventions, work on the determinants and implications of reactance has remained unpublished. Our study provides first evidence that reactance can be understood from a theoretical background (selfaffirmation theory), and that theory-based measures to reduce reactance are possible.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are a few limitations to this study. Sun exposure was measured by self-report, which may affect the reliability and validity of the behavioral outcome. However, there is evidence for the validity of sun exposure self-reports by showing satisfactory correspondence of self-reports with more objective measures such as polysulphone badges (Dwyer, Blizzard, Gies, Ashbolt, & Roy, 1996; Lower, Girgis, & Sanson-Fisher, 1998). Furthermore, the sample at the science event is not representative for the general population and thus generalizability of the study results to other populations is limited. Yet, the age and educational range of our study goes beyond other convenience and student samples. Our operationalization of risk status as the subjective importance of risk behavior might hold limited validity as an indicator of objective risk status. However, as mentioned previously, this operationalization taps into the concept of subjectively important domains of the self-system. In addition, there were slightly higher, but nonsignificant dropout rates in the control- as well as the risk feedback and selfaffirmation only groups. Participants in the control- and the selfaffirmation only groups might have been disappointed that they did not receive a personal UV photo, which might have led to lower attrition in these groups. It might also be that selfaffirmation manipulations are better accepted if they go together with risk feedback. Moreover, participants in the risk feedback only group might have been put off by completing the selfaffirmation manipulation with regard to a celebrity, as this task was seemingly unrelated to the general purpose of the study. Future studies might want to establish whether engaging participants in this control task has a potentially detrimental effect on attrition. An important yet unresolved issue that remains beyond the scope of this study relates to the mediational processes by which self-affirmation affects the reduction of reactant or defensive behavior and cognitions. The findings about the role of positive mood or self-esteem are inconclusive (e.g., Koole, Smeets, van Knippenberg, & Dijksterhuis, 1999; Steele & Liu, 1983), but there is some evidence that self-affirmation influences cognitive processes such as attention, openness to information, and structured thinking, and thereby might achieve reductions in defensive processing (Klein & Harris, 2009; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Wakslak & Trope, 2009). A recent study by Klein, Harris, Ferrer, and Zajac (2011) suggests that vulnerability could mediate the effects of selfaffirmation on behavioral intentions. In addition, it showed that selfaffirmation rather affects feelings of vulnerability than cognitive risk estimates. While our findings on risk perception replicate previous

findings in showing that self-affirmed high-risk individuals reported higher risk perception than nonaffirmed individuals (Harris & Napper, 2005), it remains to be established whether cognitive or rather affective risk estimates mediate the self-affirmation effects on risk behavior that were shown in this study. Our study only encompassed two points of measurement, thus a full mediating model testing in how far the intervention changes social cognitive mediators which in turn might affect behavior at a later point in time could not be tested. Ideally, this would be done by means of randomized controlled trials with at least three points of measurement. This study was the first to test the effectiveness of self-affirmation in combination with personalized visual risk feedback and demonstrates that the basic assumptions of self-affirmation theory also apply in this context. However, future research should concurrently test the effects of personalized risk feedback and more generic risk information to establish what kind of risk information works best in conjunction with self-affirmation manipulations.

Conclusions

Overall, our study showed that concepts derived from Social Psychology such as self-affirmation can be effectively adapted to the Health Psychology context and might give answers to evident problems in health promotion such as defensive behaviors and reactance. On the other hand, results from the Health Psychology context have impacted on theory, for example, in demonstrating that effects of self-affirmation can differ according to behavioral risk status (Harris & Napper, 2005), by suggesting that affective rather than cognitive risk indicators are affected by selfaffirmation (Klein et al., 2011), and in extending the concept of defensive responses to defensive behavior such as reactance (current article). Our results suggest that self-affirmation manipulations might be a viable option to reduce reactant behaviors in high-risk individuals, in whom personalized visual risk feedback might backfire otherwise. This has important implications for health promotion interventions, as groups with high levels of risk behavior are notoriously hard to motivate for behavior change. Our study suggests that a combined risk feedback and self-affirmation intervention might be effective in reducing defensive reactions in such high-risk target groups.

References

Ajzen, I. (2006). Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Retrieved from http://www.people .umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf Albarracn, D., Durantini, M. R., Earl, A., Gunnoe, J. B., & Leeper, J. (2008). Beyond the most willing audiences: A meta-intervention to increase exposure to HIV-prevention programs by vulnerable populations. Health Psychology, 27, 638 644. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.5 .638 Brehm, S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. New York, NY: Academic Press. Brinol, P., Petty, R. E., Gallardo, I., & DeMarree, K. G. (2007). The effect of self-affirmation in nonthreatening persuasion domains: Timing affects the process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 15331546. doi:10.1177/0146167207306282 Champely, S. (2009). pwr: Basic functions for power analysis. R package version 1.1.1. Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/packagepwr

SELF-AFFIRMATION AND PERSONALIZED RISK FEEDBACK Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J., & Steele, C. M. (2000). When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 11511164. doi:10.1177/ 01461672002611011 Cox, C. R., Cooper, D. P., Vess, M., Arndt, J., Goldenberg, J. L., & Routledge, C. (2009). Bronze is beautiful but pale can be pretty: The effects of appearance standards and mortality salience on sun-tanning outcomes. Health Psychology, 28, 746 752. doi:10.1037/a0016388 Crossley, M. L. (2002). Resistance to health promotion: A preliminary comparative investigation of British and Australian students. Health Education, 102, 289 299. doi:10.1108/09654280210446838 Dwyer, T., Blizzard, L., Gies, P. H., Ashbolt, R., & Roy, C. (1996). Assessment of habitual sun exposure in adolescents via questionnaire-a comparison with objective measurement using polysulphone badges. Melanoma Research, 6, 231239. doi:10.1097/00008390-19960600000006 Earl, A., & Albarracn, D. (2007). Nature, decay, and spiraling of the effects of fear-inducing arguments and HIV counseling and testing: A meta-analysis of the short- and long-term outcomes of HIV-prevention interventions. Health Psychology, 26, 815 816. doi:10.1037/0278-6133 .26.6.815 Edwards, K., & Smith, E. E. (1996). A disconfirmation bias in the evaluation of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 524. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.5 Eid, M. (1997). Sonnenschutzverhalten: Ein typologischer Ansatz [Sun protection behavior: A typological approach]. Zeitschrift fr Gesundheitspsychologie, 5, 7391. Epton, T., & Harris, P. R. (2008). Self-affirmation promotes health behavior change. Health Psychology, 27, 746 752. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27 .6.746 Fabrizi, G., Pagliarello, C., & Massi, G. (2008). A simple and inexpensive method for performing ultraviolet photography in your dermatology practice. Dermatologic Surgery, 34, 10931095. doi:10.1111/j.15244725.2008.34217.x Garside, R., Pearson, M., & Moxham, T. (2010). What influences the uptake of information to prevent skin cancer? A systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Education Research, 25, 162 182. doi:10.1093/her/cyp060 Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Lane, D. J., Mahler, H. I. M., & Kulik, J. A. (2005). Using UV photography to reduce use of tanning booths: A test of cognitive mediation. Health Psychology, 24, 358 363. doi:10.1037/ 0278-6133.24.4.358 Griffin, D. W., & Harris, P. R. (2011). Calibrating the responses to health warnings: Limiting both overreaction and underreaction with selfaffirmation. Psychological Science, 22, 572578. doi:10.1177/ 0956797611405678 Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2009). The impact of self-affirmation on health cognition, health behavior and other health-related responses: A narrative review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3, 962978. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00233.x Harris, P. R., Mayle, K., Mabbott, L., & Napper, L. (2007). Selfaffirmation reduces smokers defensiveness to graphic on-pack cigarette warning labels. Health Psychology, 26, 437 446. doi:10.1037/02786133.26.4.437 Harris, P. R., & Napper, L. (2005). Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1250 1263. doi:10.1177/0146167205274694 Hart, W., Albarracn, D., Eagly, A. H., Brechan, I., Lindberg, M. J., & Merrill, L. (2009). Feeling validated versus being correct: A metaanalysis of selective exposure to information. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 555588. doi:10.1037/a0015701 Hollands, G. J., Hankins, M., & Marteau, T. M. (2010). Visual feedback of individuals medical imaging results for changing health behaviour.

569

Cochrane Database System Review, CD007434. doi:10.1002/14651858 .CD007434.pub2 Jemmott, J. B., Ditto, P. H., & Croyle, R. T. (1986). Judging health status: Effects of perceived prevalence and personal relevance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 899 905. doi:10.1037/00223514.50.5.899 Jessop, D. C., Simmonds, L. V., & Sparks, P. (2009). Motivational and behavioural consequences of self-affirmation interventions: A study of sunscreen use among women. Psychology & Health, 24, 529 544. doi:10.1080/08870440801930320 Jones, J. L., & Leary, M. R. (1994). Effects of appearance-based admonitions against sun exposure on tanning intentions in young adults. Health Psychology, 13, 86 90. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.13.1.86 Klein, W. M. P., & Harris, P. R. (2009). Self-affirmation enhances attentional bias toward threatening components of a persuasive message. Psychological Science, 20, 14631467. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009 .02467.x Klein, W. M. P., Harris, P. R., Ferrer, R. A., & Zajac, L. E. (2011). Feelings of vulnerability in response to threatening messages: Effects of selfaffirmation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 12371242. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.005 Koole, S. L., Smeets, K., van Knippenberg, A., & Dijksterhuis, A. (1999). The cessation of rumination through self-affirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 111125. doi:10.1037/0022-3514 .77.1.111 Lower, T., Girgis, A., & Sanson-Fisher, R. (1998). How valid is adolescents self-report as a way of assessing sun protection practices? Preventive Medicine, 27, 385390. doi:10.1006/pmed.1998.0252 Mahler, H. I. M., Kulik, J. A., Gerrard, M., & Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Long-term effects of appearance-based interventions on sun protection behaviors. Health Psychology, 26, 350 360. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.26 .3.350 Mahler, H. I. M., Kulik, J. A., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., & Harrell, J. (2003). Effects of appearance-based intervention on sun protection intentions and self-reported behaviors. Health Psychology, 22, 199 209. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.199 McQueen, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2006). Experimental manipulations of self-affirmation: A systematic review. Self and Identity, 5, 289 354. doi:10.1080/15298860600805325 Napper, L., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2009). Developing and testing a self-affirmation manipulation. Self and Identity, 8, 45 62. doi:10.1080/ 15298860802079786 Noguchi, K., Albarracn, D., Durantini, M. R., & Glasman, L. R. (2007). Who participates in which health promotion programs? A meta-analysis of motivations underlying Enrollment and retention in HIV-Prevention interventions. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 955975. doi:10.1037/00332909.133.6.955 Ramones, The. (1980). Rock n roll high school. On End of the Century [CD]. New York, NY: Sire Records. R Development Core Team. (2010). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Development Core Team. Reed, M. B., & Aspinwall, L. G. (1998). Self-affirmation reduces biased processing of health-risk information. Motivation and Emotion, 22, 99 132. doi:10.1023/A:1021463221281 Schz, B., Wiedemann, A. U., Mallach, N., & Scholz, U. (2009). Effects of a short behavioural intervention for dental flossing: Randomizedcontrolled trial on planning when, where and how. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 36, 498 505. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01406.x Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 129. doi:10.1111/j.14640597.2007.00325.x

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

570

SCHZ, SCHZ, AND EID Urbaniak, G. C., & Plous, S. (2009). Research randomizer. Retrieved from http://www.randomizer.org van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Das, E., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R. (2009). How self-affirmation reduces defensive processing of threatening health information: Evidence at the implicit level. Health Psychology, 28, 563568. doi:10.1037/a0015610 Wakslak, C. J., & Trope, Y. (2009). Cognitive consequences of affirming the self: The relationship between self-affirmation and object construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 927932. doi:10.1016/ j.jesp.2009.05.002 Weinstein, N. D., & Sandman, P. M. (1992). A model of the precaution adoption process: Evidence from home radon testing. Health Psychology, 11, 170 180. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.11.3.170

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Sherman, D. K., & Cohen, G. L. (2006). The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 38, pp. 183242). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press Inc. Sherman, D. K., Nelson, L. D., & Steele, C. M. (2000). Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1046 1058. doi:10.1177/01461672002611003 Skin Cancer Foundation. (2008). Year-round sun protection. Retrieved from http://www.skincancer.org/year-round-sun-protection.html Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 261302). New York, NY: Academic Press. Steele, C. M., & Liu, T. J. (1983). Dissonance processes as selfaffirmation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 519. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.1.5 Taylor, C. R., Stern, R. S., Leyden, J. J., & Gilchrest, B. A. (1990). Photoaging/photodamage and photoprotection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 22, 115. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90) 70001-X

Received June 1, 2011 Revision received November 29, 2011 Accepted December 2, 2011

You might also like

- Children & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsFrom EverandChildren & Adolescents with Problematic Sexual BehaviorsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Psychology of Self Defense: Self Affirmation Theory: David K. Sherman Geo Vrey L. CohenDocument60 pagesThe Psychology of Self Defense: Self Affirmation Theory: David K. Sherman Geo Vrey L. CohenKanji HisamotoNo ratings yet

- Resilience Theory Lit ReviewDocument28 pagesResilience Theory Lit Reviewapi-383927705100% (1)

- Terapi Berhenti MerokokDocument19 pagesTerapi Berhenti MerokokTrisa Pradnja ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Health Message Framing Effects On Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-Analytic ReviewDocument16 pagesHealth Message Framing Effects On Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Meta-Analytic ReviewDaniel EidNo ratings yet

- Resilience in ChildrenDocument27 pagesResilience in Childrenapi-383927705No ratings yet

- Alternative Measures To RestraintsDocument11 pagesAlternative Measures To Restraintsapi-301611629No ratings yet

- An Experimental Test of Women's Body Dissatisfaction Reduction Through Self-AffirmationDocument14 pagesAn Experimental Test of Women's Body Dissatisfaction Reduction Through Self-AffirmationMihaela-AlexandraGhermanNo ratings yet

- Wells.1995.Social Phobia: The Role of In-Situation Safety Behaviors in Maintaining Anxiety and Negative BeliefsDocument9 pagesWells.1995.Social Phobia: The Role of In-Situation Safety Behaviors in Maintaining Anxiety and Negative BeliefsGanellNo ratings yet

- Lit Review Resilience TheoryDocument27 pagesLit Review Resilience TheoryAnthony Solina100% (3)

- Resilience in Cancer Patients Explored Through Qualitative InterviewsDocument44 pagesResilience in Cancer Patients Explored Through Qualitative InterviewsTasha NurmeilitaNo ratings yet

- The Health Belief Model: Edward C. Green, Elaine M. Murphy, and Kristina GryboskiDocument4 pagesThe Health Belief Model: Edward C. Green, Elaine M. Murphy, and Kristina Gryboskiakbar.maulanaali05100% (1)

- Behaviour Research and Therapy: Irena Milosevic, Adam S. RadomskyDocument8 pagesBehaviour Research and Therapy: Irena Milosevic, Adam S. RadomskynegrodanNo ratings yet

- Reino UnidoDocument10 pagesReino UnidoaxNo ratings yet

- Defense Reactions and Coping Strategies in Normal AdolescentsDocument12 pagesDefense Reactions and Coping Strategies in Normal AdolescentsGergőKoplányiNo ratings yet

- Psychological Reports: Disability & TraumaDocument22 pagesPsychological Reports: Disability & TraumaEdiputriNo ratings yet

- Nudge To Health: Harnessing Decision Research To Promote Health BehaviorDocument12 pagesNudge To Health: Harnessing Decision Research To Promote Health BehaviorLiliNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsDocument15 pagesRelationship of Resilience To Personality, Coping, and Psychiatric Symptoms in Young AdultsBogdan Hadarag100% (1)

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument6 pagesReview of Related LiteratureAj BrarNo ratings yet

- An Integrative Model of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior: Heidi J. Keeler RN, BSN, Margaret M. Kaiser PHD, Aprn-CnsDocument12 pagesAn Integrative Model of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior: Heidi J. Keeler RN, BSN, Margaret M. Kaiser PHD, Aprn-Cnshafid nugrohoNo ratings yet

- 05 Health Belief ModelDocument7 pages05 Health Belief ModelMohammed AdusNo ratings yet

- Psycho-Dynamic Learning TheoryDocument10 pagesPsycho-Dynamic Learning TheoryFrancis GecobeNo ratings yet

- Preventative StrategiesDocument23 pagesPreventative Strategiesnegel shanNo ratings yet

- Advances in Consumer Research - White Paper CollectionDocument94 pagesAdvances in Consumer Research - White Paper Collectionglen_durrantNo ratings yet

- Health Belief ModelDocument8 pagesHealth Belief ModelJose Espinosa Evangelista Jr.100% (4)

- LEVEL of STRESS Research ProposalDocument30 pagesLEVEL of STRESS Research ProposalArvin Ian Penaflor100% (2)

- Effectiveness of Coping Strategies in Reducing Student's Academic StressDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of Coping Strategies in Reducing Student's Academic StressFathur RNo ratings yet

- Gabie Et Al. 1997Document10 pagesGabie Et Al. 1997thaiane_machadoNo ratings yet

- Early Detection and Prevention of Mental Health Problems Developmental Epidemiology and Systems of SupportDocument9 pagesEarly Detection and Prevention of Mental Health Problems Developmental Epidemiology and Systems of SupportsantiNo ratings yet

- Stress Effects on Nursing Student Clinical PerformanceDocument13 pagesStress Effects on Nursing Student Clinical Performancealou_saludesNo ratings yet

- SB - The Safety Behavior Assessment Form - Development and ValidationDocument13 pagesSB - The Safety Behavior Assessment Form - Development and ValidationfpNo ratings yet

- Resilience To Emotional DistressDocument55 pagesResilience To Emotional DistressCarlota Recio SuárezNo ratings yet

- Health Belief Model - Behavioural ChangeDocument3 pagesHealth Belief Model - Behavioural ChangenieotyagiNo ratings yet

- Ncm102 Purposive Assignment RSRCHDocument44 pagesNcm102 Purposive Assignment RSRCHleehiNo ratings yet

- Health Belief Model HandoutDocument2 pagesHealth Belief Model HandoutRIK HAROLD GATPANDANNo ratings yet

- Coping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDocument14 pagesCoping, Stress, and Negative Childhood Experiences The Link To Psychopathology, Self-Harm, and Suicidal BehaviorDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Clinical ResearchDocument3 pagesEthics in Clinical ResearchAPLCTN100% (1)

- Schuengel 2006Document32 pagesSchuengel 2006AmyatenaNo ratings yet

- Human BehaviorDocument3 pagesHuman BehaviorLuo MiyandaNo ratings yet

- Health Belief Model UpdateDocument15 pagesHealth Belief Model Updatejust nomiNo ratings yet

- Framework Analysis - PatalitaDocument2 pagesFramework Analysis - PatalitaAxe Pulse PatalitaNo ratings yet

- Guttman - On Being Responsabile - Health CampaignDocument20 pagesGuttman - On Being Responsabile - Health CampaignColesniuc AdinaNo ratings yet

- Presentation From: Health Psychology Topics CoveredDocument18 pagesPresentation From: Health Psychology Topics CoveredAkhil VrNo ratings yet

- HMB Weight ManagementDocument5 pagesHMB Weight ManagementJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Effective: and Ineffective Use of Fear inDocument6 pagesEffective: and Ineffective Use of Fear intrisnaNo ratings yet

- Social Safety Theory and immune system threats to healthDocument2 pagesSocial Safety Theory and immune system threats to healthAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Self Compassion and Self HandicappingDocument6 pagesSelf Compassion and Self HandicappingAnnaNedelcuNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Carole Doherty, Charitini StavropoulouDocument7 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Carole Doherty, Charitini Stavropouloube a doctor for you Medical studentNo ratings yet

- Physician Resilience What It Means, Why It.12Document3 pagesPhysician Resilience What It Means, Why It.12Fernando Miguel López DomínguezNo ratings yet

- About Vaccination. Two Needed ChangesDocument4 pagesAbout Vaccination. Two Needed ChangesferminjgmNo ratings yet

- Nursing Theory: Betty Neuman's: By: Harpreet Kaur M.Sc. 1 YearDocument34 pagesNursing Theory: Betty Neuman's: By: Harpreet Kaur M.Sc. 1 YearSimran JosanNo ratings yet

- Fear Appeal TheoryDocument21 pagesFear Appeal TheoryTabaloc Mae JoyNo ratings yet

- dianap2Document8 pagesdianap2Diana PrietoNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Patient Education - Theory and PracticeDocument7 pagesAn Introduction To Patient Education - Theory and PracticeCarla PereiraNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Health Belief Model and Concept of SelfDocument14 pagesSeminar On Health Belief Model and Concept of SelfSAGAR ADHAO100% (1)

- Healt MODELS TheoriesDocument6 pagesHealt MODELS TheoriesDthird Mendoza ClaudioNo ratings yet

- Teori HBMDocument15 pagesTeori HBMIwan Suryadi MahmudNo ratings yet

- Zimmerman et al., 2020Document16 pagesZimmerman et al., 2020Just a GirlNo ratings yet

- Exposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodFrom EverandExposure Therapy: Rethinking the Model - Refining the MethodPeter NeudeckNo ratings yet

- Pas 24 1 11Document10 pagesPas 24 1 11Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Dev 43 6 1474Document10 pagesDev 43 6 1474Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Bul 137 3 421Document22 pagesBul 137 3 421Catarina C.No ratings yet

- PSP 102 6 1289Document15 pagesPSP 102 6 1289Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Journal of Experimental Psychology: GeneralDocument10 pagesJournal of Experimental Psychology: GeneralCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Pag 26 4 803Document10 pagesPag 26 4 803Catarina C.No ratings yet

- 88950257Document16 pages88950257Catarina C.No ratings yet

- 2012 02792 001Document10 pages2012 02792 001Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Vohs Park Schmeichel 2013Self-Affirmation Can Enable Goal DisengagementDocument14 pagesVohs Park Schmeichel 2013Self-Affirmation Can Enable Goal DisengagementEneCrsNo ratings yet

- Spy 1 S 49Document11 pagesSpy 1 S 49Catarina C.No ratings yet

- PSP 102 3 562Document14 pagesPSP 102 3 562Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Passionate Thinkers Feel BetterDocument7 pagesPassionate Thinkers Feel BetterCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Int 21 3 280Document28 pagesInt 21 3 280Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Pag 26 4 803Document10 pagesPag 26 4 803Catarina C.No ratings yet

- 2012 16772 001Document12 pages2012 16772 001Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Edu 103 3 649Document15 pagesEdu 103 3 649Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Int 21 3 280Document28 pagesInt 21 3 280Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Int 21 3 280Document28 pagesInt 21 3 280Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Self-Esteem, Self-Affirmation, and Schadenfreude: Brief ReportDocument5 pagesSelf-Esteem, Self-Affirmation, and Schadenfreude: Brief ReportCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Developmental Psychology: Moral Identity As Moral Ideal Self: Links To Adolescent OutcomesDocument14 pagesDevelopmental Psychology: Moral Identity As Moral Ideal Self: Links To Adolescent OutcomesCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Retraction of Blanton and Stapel (2008)Document1 pageRetraction of Blanton and Stapel (2008)Catarina C.No ratings yet

- A Review of Client Self-Criticism in Psychotherapy: Divya Kannan Heidi M. LevittDocument13 pagesA Review of Client Self-Criticism in Psychotherapy: Divya Kannan Heidi M. LevittCatarina C.100% (1)

- Mind-Sets Matter: A Meta-Analytic Review of Implicit Theories and Self-RegulationDocument47 pagesMind-Sets Matter: A Meta-Analytic Review of Implicit Theories and Self-RegulationCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Role of Self-Control Strength in The Relation Between Anxiety and Cognitive PerformanceDocument13 pagesRole of Self-Control Strength in The Relation Between Anxiety and Cognitive PerformanceCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Self-Efficacy As A Predictor of Musical Performance Quality: Laura Ritchie Aaron WilliamonDocument7 pagesSelf-Efficacy As A Predictor of Musical Performance Quality: Laura Ritchie Aaron WilliamonCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Ser 9 3 240Document8 pagesSer 9 3 240Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Psychology of Men & MasculinityDocument8 pagesPsychology of Men & MasculinityCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Self and External Monitoring of Reading Comprehension: Ling-Po Shiu Qishan ChenDocument11 pagesSelf and External Monitoring of Reading Comprehension: Ling-Po Shiu Qishan ChenCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Brief Report: Rachel Varley, Thomas L. Webb, and Paschal SheeranDocument6 pagesBrief Report: Rachel Varley, Thomas L. Webb, and Paschal SheeranCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Health Benefits of Vitamin CDocument5 pagesHealth Benefits of Vitamin CZackNo ratings yet

- Speech & Language Therapy in Practice, Spring 1998Document32 pagesSpeech & Language Therapy in Practice, Spring 1998Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeNo ratings yet

- Tiger NutsDocument4 pagesTiger NutsMohd Idris MohiuddinNo ratings yet

- Trichiasis: Prepared By:pooja Adhikari Roll No.: 27 SMTCDocument27 pagesTrichiasis: Prepared By:pooja Adhikari Roll No.: 27 SMTCsushma shresthaNo ratings yet

- Common mental health problems screeningDocument5 pagesCommon mental health problems screeningSaralys MendietaNo ratings yet

- (ACV-S05) Quiz - Health & Wellness - INGLES IV (11935)Document3 pages(ACV-S05) Quiz - Health & Wellness - INGLES IV (11935)Erika Rosario Rodriguez CcolqqueNo ratings yet

- Efolio 404Document7 pagesEfolio 404api-377789171No ratings yet

- PEH 11 Q3 Mod1 Week 1 2 MELC01 Thelma R. SacsacDocument16 pagesPEH 11 Q3 Mod1 Week 1 2 MELC01 Thelma R. Sacsaccalvin adralesNo ratings yet

- DentaPure Sell SheetDocument2 pagesDentaPure Sell SheetJeff HowesNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009Document22 pagesExecutive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009Musaab SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- VaanannanDocument53 pagesVaanannankevalNo ratings yet

- Dr. Sanjida Sultana's CVDocument4 pagesDr. Sanjida Sultana's CVHasibul Hassan ShantoNo ratings yet

- Sensors: Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Tools: From Research To Practice (A Workshop Summary)Document20 pagesSensors: Low-Cost Air Quality Monitoring Tools: From Research To Practice (A Workshop Summary)SATRIONo ratings yet

- Leila Americano Yucheng Fan Carolina Gonzalez Manci LiDocument21 pagesLeila Americano Yucheng Fan Carolina Gonzalez Manci LiKarolllinaaa100% (1)

- The Diabetic FootDocument33 pagesThe Diabetic Footpagar bersihNo ratings yet

- New ? Environmental Protection Essay 2022 - Let's Save Our EnvironmentDocument22 pagesNew ? Environmental Protection Essay 2022 - Let's Save Our EnvironmentTaba TaraNo ratings yet

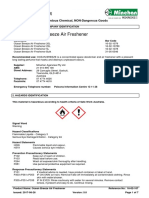

- Ocean Breeze Air Freshener: Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesOcean Breeze Air Freshener: Safety Data SheetMark DunhillNo ratings yet

- ExplanationDocument6 pagesExplanationLerma PagcaliwanganNo ratings yet

- 2019 - Asupan Zat Gizi Makro Dan Mikro Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada BalitaDocument6 pages2019 - Asupan Zat Gizi Makro Dan Mikro Terhadap Kejadian Stunting Pada BalitaDemsa SimbolonNo ratings yet

- Healthy and Unhealthy Relationships LessonDocument13 pagesHealthy and Unhealthy Relationships Lessonapi-601042997No ratings yet

- Snigdha Dasgupta Sexual DisorderDocument13 pagesSnigdha Dasgupta Sexual DisorderSNIGDHA DASGUPTANo ratings yet

- Psychological Psychoeducational Neuropsychological Assessment Information For Adults Families 1Document3 pagesPsychological Psychoeducational Neuropsychological Assessment Information For Adults Families 1ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Successful Strategy To Decrease Indwelling Catheter Utilization Rates inDocument7 pagesSuccessful Strategy To Decrease Indwelling Catheter Utilization Rates inWardah Fauziah El SofwanNo ratings yet

- ACN 3 Knowledge Regarding Water Born Diseases and Its PreventionDocument5 pagesACN 3 Knowledge Regarding Water Born Diseases and Its PreventionFouzia GillNo ratings yet

- Medical BacteriologyDocument108 pagesMedical BacteriologyTamarah YassinNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3: Health Information System How Do Health Information Systems Look Like and What Architectures Are Appropriate?Document13 pagesLesson 3: Health Information System How Do Health Information Systems Look Like and What Architectures Are Appropriate?ajengwedaNo ratings yet

- Passive Smoking PDFDocument69 pagesPassive Smoking PDFjeffrey domosmogNo ratings yet

- Mega BlueDocument9 pagesMega Bluepollito AmarilloNo ratings yet

- Fasd - A ChecklistDocument3 pagesFasd - A Checklistapi-287219512No ratings yet

- Health and SafetyDocument26 pagesHealth and SafetyReza NugrahaNo ratings yet