Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cohn - Early Discussions Free Indirect Style 05

Uploaded by

lily briscoeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cohn - Early Discussions Free Indirect Style 05

Uploaded by

lily briscoeCopyright:

Available Formats

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

Translated by Dorrit Cohn

Germanic Languages and Literatures and Comparative Literature, Harvard

Translators Preface

Readers of modern views on free indirect style (as the form is known in English) are rarely aware that this phenomenon was discovered, and intensively discussed in French and German, as early as the rst decades of the twentieth century. For this reason, I have translated a series of articles that were published in Germanisch-Romanische Monatsschrift (GRM )one of the journals most interested in the questionin the years immediately preceding World War I. Though I have abbreviated them (and as a result altered some of their details), I have tried to keep their main arguments intact. These arguments revolve around the nature of free indirect style whether it is a form of quotation or a factual report by the narratorand consequently the name to be applied to it: Ballys style indirect libre (free indirect style), or Kalepkys verschleierte Rede (veiled discourse), or Lerchs Imperfektum der Rede (imperfect of discourse).1 Bally, a student of de Saussure, writing in French, represents the school of Geneva in regarding free indirect style as an objective and purely literary phenomenon. Kalepky and Lerch, students of Vossler, writing in German, represent the school of Munich in regarding free indirect style as a subjective phenomenon in which the narrator adopts the viewpoint of a character, and they look for its origin in spoken language. Thus the rst scholars regard the form as grammatically

1. Its standard German phrasing today is erlebte Rede. Poetics Today 26:3 (Fall 2005). Copyright 2005 by the Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics.

502

Poetics Today 26:3

static, the second as psychologically evolutive, a disagreement which is still greatly at issue in todays discussions of the subject. The translation of quoted passages is my own. Free Indirect Style in Modern French by Charles Bally, University of Geneva GRM 4 (1912): 54956, 597606 Indirect style includes, as we know, the whole range of the syntactical forms that reproduce the words and thoughts of a third person (cf. Paul viendra and Pierre disait, pensait que Paul viendrait ), these forms being used by extension to reproduce the subjects own words and thoughts (cf. Paul viendra and Paul disait, pensait quil viendrait ). I assume that the modications by which direct enunciation is transformed into indirect style are well known; I limit myself to remind my reader that this form is characterized by the presence of an introductory verb (of saying or believing: dire, annoncer, penser, croire, etc.); by a number of grammatical words (que, si, ce qui, ce que [for quest-ce qui, quest-ce que], cf.: Quest-ce qui empche Paul de venir? and Pierre demande ce qui empche Paul, etc.); nally, by the transformations that aect the tenses, the modes, and the persons of the verb in passing from direct to indirect form. In his interesting work Der Stil der franzsischen Sprache (pp. 297f.), Mr. F. Strohmeyer remarks that French avoids indirect style, and in his opinion, this avoidance is increased because our language cannot, like German, introduce one or more indirect sentences without the help of a subordinating conjunction. . . . This assertion is not exact in its generality: French knows a free indirect style that is not conjectural, analogous to the one in German; but the fact is that grammars ignore it almost completely, because they are ordinarily based on classical language, where this free form is an exception, whereas it developed widely in the literary language of the past hundred years.We will describe this free indirect style and its principal variations; this will allow us to explain certain facts of temporal syntax to which is generally given a dierent interpretation; nally, we will ask ourselves if the grammarians ignorance of free indirect style is not related to a defect in method that we will dene at the end of this study. . . . Mr. Strohmeyer is right in saying that indirect style using subordination disagrees with modern French; we make a face when a sentence contains too many qui and que; all artistic manuals advise avoiding them. . . . Yet French has an indirect style that gives the illusion of direct speech, even as it transposes the words and thoughts by the use of tenses proper to indirect style. . . . The following passage from Mrime shows the procedure with which we are concerned in its full extension:

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

503

Cetait peut-tre la premire fois quun dsir manifest, par le colonel et obtenu lapprobation de sa lle. Enchant de cette rencontre inattendue, il eut pourtant le bon sens de faire quelques objections pour irriter lheureux caprice de miss Lydia. En vain il parla de la sauvagerie du pays et de la dicult pour une femme dy voyager: ELLE NE CRAIGNAIT RIEN; ELLE AIMAIT AVANT TOUT VOYAGER CHEVAL; ELLE SE FAISAIT UNE FTE DE COUCHER AU BIVAC; elle menaait daller en Asie Mineure. Bref, elle avait rponse tout, car JAMAIS ANGLAISE NAVAIT T EN CORSE; DONC ELLE DEVAIT Y ALLER. ET QUEL BONHEUR, DE RETOUR SAINT-JAMES PLACE, DE MONTRER SON ALBUM! Pourquoi donc, ma chre, passez-vous ce charmant dessein?Oh! ce nest rien. Cest un croquis que jai fait daprs un fameux bandit corse qui nous a servi de guide.Comment! vous avez t en Corse? . . . (Colomba) [It was perhaps the rst time that a desire of the colonel received the agreement of his daughter. Delighted by this unexpected encounter, he nonetheless had the good sense to make a few objections to irritate this happy caprice of miss Lydias. He spoke in vain of the wildness of the country and of the diculty for a woman to travel in it: SHE WAS NOT AFRAID OF ANYTHING; SHE LIKED ABOVE ALL TO TRAVEL ON HORSEBACK; SHE ESPECIALLY ENJOYED SLEEPING IN THE OPEN AIR; she threatened to go to the Near East. In short, she had an answer to everything, because AN ENGLISH WOMAN HAD NEVER BEEN TO CORSICA; THUS SHE HAD TO GO THERE. AND WHAT A PLEASURE TO SHOW HER ALBUM WHEN SHE RETURNED TO SAINT JAMES PLACE! Why, my dear, did you pass by this charming drawing?Oh! its nothing. Its only a sketch I made of a famous Corsican bandit who served as our guide.What! you have been to Corsica? . . .]

Let us now examine more closely the dierent forms taken by the free indirect style; let us see how it distances itself gradually from the classical form of indirect discourse and how it approaches more and more the pure direct style. . . . We will order the following examples accordingly. (a) The statement is introduced by three subordinating conjunctions; the remainder does without conjunctions:

La mouche, en ce commun besoin, Se plaint quelle agit seule et quelle a tout le soin, Quaucun naide aux chevaux se tirer daaire; LE MOINE DISAIT SON BRVIAIRE: IL PRENAIT BIEN SON TEMPS! UNE FEMME CHANTAIT; CTAIT BIEN DE CHANSONS QUALORS IL SAGISSAIT! (La Fontaine, La mouche du coche) [The y, in this common need, Complains that it acts all alone and that it has all the work, That no one helps the horses to cope; THE MONK RECITED HIS BREVIARY; HE TOOK ALL HIS TIME! A WOMAN SANG; IT WAS SURELY SONGS THAT WERE NEEDED THEN!]

(b) Only two conjunctions open the indirect discourse, the remainder has the free form:

504

Poetics Today 26:3

Locier sappliquait de grands coups de poing, en disant que lui, ntait pas un bourreau, que, sil y en avait qui tuaient les innocents, ce ntait pas lui; ELLE NAVAIT PAS T CONDAMNE, IL SE COUPERAIT LA MAIN PLUTT QUE DE TOUCHER UN CHEVEU DE SA TTE. (Zola, Dbcle) [The ocer gave himself big punches, saying that he was not an executioner, that, if there were some people who killed the innocent, he wasnt one of them; SHE HAD NOT BEEN CONDEMNED, HE WOULD CUT OFF HIS HAND RATHER THAN TOUCH A HAIR ON HER HEAD.]

(c) Only the rst proposition is subordinated:

Lenfant, subitement mis en conance, raconta quil tait tranger la ville; SES PARENTS HABITAIENT AUX ENVIRONS DE DAVERY; IL RETOURNERAIT EN VACANCES CHEZ SON PRE; MAIS PARIS, ON LUI AVAIT VOL SON PORTE-MONNAIE, etc. (G. Lentre) [The child, suddenly trusting, told that he was a stranger in the city; HIS PARENTS LIVED NEAR DAVERY; HE WOULD RETURN TO SPEND HIS VACATIONS AT HIS FATHERS HOUSE; BUT IN PARIS, THEY STOLE HIS PURSE, etc.]

(d) Finally, every external trace of subordination can disappear; for this to happen, it is sucient that the introductory verb of the indirect style be intransitive and that it cannot therefore be followed by a sentence with que (e.g., parler, ajouter foi, tre embarass, semporter, etc.) or else that the verb has already a direct substantive regime excluding a subordinating conjunction (e.g., dire son mot, ne rien cacher, exhaler sa colre, etc.). In all these cases, regular syntax would demand the injection of a verb of saying or believing, and it is precisely the absence of such a verb that constitutes the free indirect style. . . . Here is an example:

Elle [Sappho] se mit lui parler longuement de sa famille, ce quelle avait toujours vit; CTAIT SI LAID, SI BAS . . . ; MAIS ON SE CONNAISSAIT MIEUX MAINTENANT, ON NAVAIT PLUS RIEN SE CACHER. (A. Daudet, Sappho) [She {Sappho} began speaking to him at length about her family, a thing she had always avoided: IT WAS SO UGLY, SO LOW . . . ; BUT THEY KNEW EACH OTHER BETTER NOW, THEY HAD NOTHING TO HIDE FROM EACH OTHER.]

(e) In all the examples seen up to this point, the introductory verb, if it was not clearly a verb of thinking or saying, allowed one at least to reconstitute in thought a verb of this category. We shall see that the introductory verb can be absent altogether. This is the most interesting case, since the grammars, by ignoring free indirect style, interpret it quite dierently. Here is a clear example:

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

505

Tout coup ils virent entrer par la barrire M. Lheureux, le marchand dtoes. IL VENAIT OFFRIR SES SERVICES, EU GARD LA FATALE CIRCONSTANCE. Emma rpondit quelle croyait pouvoir sen passer. (Flaubert, Madame Bovary [pt.] III, [chap.] 2) [All of a sudden they saw M. Lheureux, the fabric salesman, enter through the barrier. HE CAME TO OFFER HIS SERVICES, GIVEN THE FATAL CIRCUMSTANCE. Emma answered that she believed she could do without them.]

This example suggests analogous interpretations for syntactical cases that one explains quite dierently. Thus the conditional, or more exactly the imperfect of the future, is often nothing but a future transposed into indirect style. We can see it in the following passage, which oers nothing particular; but traditional grammar, based on grammatical forms rather than forms of thought, makes this into a special case:

La nuit lcrasait; ELLE NE FINIRAIT JAMAIS; CE SERAIT TOUJOURS AINSI; IL Y AVAIT DES MOIS QUIL TAIT L! (R. Rolland, Jean Christophe) [The night crushed him; SHE WOULD NEVER FINISH; IT WOULD ALWAYS BE LIKE THAT; IT WAS MONTHS HE WAS THERE!]

The conditional has no special value in the syntax of the indirect style; it is simply the tense that corresponds to the future of direct style. . . . Free indirect style being an intermediary form, there is reason to expect a passage to one or the other of the extreme forms. . . . Thus free indirect style can easily end in direct discourse:

Elle sattablait, lenfant sur ses genoux . . . et elle se mettait chercher, dtailler la ressemblance de la petite avec eux deux. Un trait tait lui, un autre elle. CEST TON NEZ, CEST MES YEUX. VOIS-TU, VOIL TES MAINS . . . CEST TOUT TOI. (Goncourt, Germinie Lacerteux) [She sat down at the table, the child on her knees . . . and she began to look for, to detail the likeness of the little one to the two of them. One trait was his, another hers. SHE HAS YOUR NOSE, SHE HAS MY EYES. YOU SEE, SHE HAS YOUR HANDS . . . ALTOGETHER LIKE YOU.]

But the inverse case is frequently found as well:

[Emma Bovary chats with Lon]: Vous vous tes donc dcide rester? ajouta-t-il. Oui, dit-elle et jai eu tort. Il ne faut pas saccoutumer des plaisirs impracticables, quand on a autour de soi mille exigences. . . .Oh! je mimagine. . . .Eh! non, car vous ntes pas une femme. MAIS LES HOMMES AUSSI AVAIENT LEURS CHAGRINS, et la conversation sengagea par quelques rexions philosophiques. (Flaubert, Madame Bovary [pt.] III, [chap.] l) [You decided to stay after all? he added.Yes, she said, and I was wrong. We must not get used to impractical pleasures when we have a thousand require-

506

Poetics Today 26:3

ments around us. . . .Oh! I imagine. . . .Oh! no, because you are not a woman. BUT MEN TOO HAD THEIR SORROWS, and the conversation continued with some philosophical reections.]

Free indirect style extends its action, outside the enunciation of the words or the thoughts, to the introductory verb itself; by a sort of construction ad sensum, this verb is attracted by the verbs of the enunciation and is used in the same tense. The clearest case is the one where the verb is interpolated. . . . With reference to the passage of Mrime quoted earlier, in reestablishing the direct style, one would obtain: (La lle du colonel rpondit:) Je ne crains rien; jaime par dessus tout voyager cheval; je me fais une fte de coucher au bivac [{The daughter of the colonel answered:} I am not afraid of anything; I like above all to travel on horseback; I enjoy especially sleeping in the open air.] Up to this point, everything is in order; but it is impossible that the young girl added: JE MENACE daller en Asie Mineure [I threaten to go to the Near East]; this part of her answer had to be: (Si lon naccde pas mon dsir), jirai en Asie Mineure [{If one does not listen to my wish}, Ill go to the Near East]; menaait is a declarative verb surrounded by indirect imperfects and attracted by them. . . . The description of free indirect style made earlier shows that this form of expression benets from an almost absolute syntactical freedom; in extreme cases, those where the independence of the indirect verb is complete, one cannot even speak of indirect style; there is more generally a subjective aspect of thought. It seems to me that it is this subjective nuance that allows one to explain certain uses of the imperfect which grammarians interpret too subtly to be correct. They are actually subjective imperfects. For example, this sentence by Alphonse Daudet: Comme il [Jack] mettait le pied sur lchelle . . . une longue secousse branla le navire; la vapeur qui grondait depuis le matin rgularisa son bruit; lhlice se mit en branle. ON PARTAIT. [As he ( Jack) put his foot on the ladder, a long jolt shook the ship; the steam which roared since morning regularized its noise; the propeller was set in motion. ONE WAS LEAVING.] We could say (and this is the interpretation that Strohmeyer would give, p. 44) that on partait marks an event thought of aectively, that it makes a picture, whereas on partit would designate simply an event that follows upon the preceding ones. I believe that there is a more essential dierence between these two tenses. On partait [one was leaving] means roughly: videmment on partait, il fallait croire quon partait [Evidently one was leaving; one had to think one was leaving], which is to say that the described indices (the jerk, the regular noise of the steam, the movement of the propeller) make one conclude that departure is imminent, much more, that this conclusion is drawn by Jack himself; as though he had said: Tiens! il parait quon part. [it seems like we are leaving.]

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

507

I insist on the particular character of this explication; between it and the one of the grammarians mentioned, there is more than a nuance; mine supposes a true transposition of the objective into the subjective; those imperfects do not indicate a particular manner in which the facts themselves are envisioned; they show that these facts have passed through the brain of a subject on the scene of a narrative or of a subject that one can easily imagine. That is why the imperfects called here subjective are essentially of the same nature as those of free indirect style. . . . Finally, I cannot help reecting on the manner in which this entire question isor rather is nottreated in French grammars. Why is free indirect style nowhere mentioned in them? . . . The reason is simple: free indirect style is a form of thought, and the grammarians take as their basis grammatical forms. The fact that one does not see how greatly this method paralyzes syntactical studies is astonishing. . . . If our study of free indirect style seems satisfactory, it will perhaps show the necessity to change the orientation of descriptive grammars. On Free Indirect Style (Veiled Discourse) by Th. Kalepky, University of Berlin GRM 5 (1913): 60819 In a very thorough and astute article in this journal, Mr. Bally has considered a stylistic representation that has attained an unusual popularity in modern narrative literature; he skillfully and appealingly calls it free indirect stylein distinction from the real, the true indirect style. After careful presentation of its genesis and development from the latter, he shows dierent highly conspicuous traits which he cannot explain in any other way than by supposing an attraction, i.e., an inuence of the linguistic form of surrounding parts that runs counter to strict logic. He is undoubtedly right that it is in fact impossible to transform some passages represented by free indirect style to direct speech by the customary change in tense and person. He shows this clearly and distinctly, for example, in the following passage from Mrimes Colomba: elle ne craignait rien, elle aimait par-dessus tout voyager, elle se faisait une fte de coucher au bivac, ELLE MENAAIT DALLER EN ASIE MINEURE [she was not afraid of anything, she liked above all to travel, she especially enjoyed sleeping in the open air, SHE THREATENED TO GO TO THE NEAR EAST], where the rst part of this discourse of the heroine (in free indirect style) is easily converted into true direct speech by a mere change of the third person into the rst and of the preterite into the present, whereas this is nonsensical for the last part (here in capitals). Mr. Bally rightly says: It is impossible that the young girl added [in direct speech] Je menace daller en Asie Mineure [I threaten to go to the Near

508

Poetics Today 26:3

East]; this part of her answer had to be: (Si lon naccde pas mon dsir), jirai en Asie Mineure! [(If one does not listen to my wish,) Ill go to the Near East]; and he adds as explanation: menaait is a declarative verb, surrounded by indirect imperfects and attracted by them. There is nothing in principle against such an attempt at explanation. It is well known and generally accepted that attraction, i.e., an inuence that goes counter to the rules of linguistic logic, is one of the most meaningful factors in the shaping of expressions in all languages. . . . However, in the case before us there seems to be a way of understanding it that does not need to have recourse to attraction; nor does it take into account only the diculties touched on by Mr. Bally; it also considers some others, on which he did not touch. . . . The fact is that the conspicuousness and diculty which face us in a more exact examination of free indirect style are not limited to the temporal side of the question, which Mr. Bally examined thoroughly, . . . but they extend much further, particularly to the region of person. . . . There are places where quite unexpectedly imperatives (thus cases of second person) or exclamations like Mon Dieu [My God] (thus rst person) appear. . . . For example: Elle [the little Sophie, miraculously cured in Lourdes] dut encore, sur une question de madame de Jonquire, raconter lhistoire des bottines que madame la comtesse [after the healing of her lameness] lui avait donnes et avec lesquelles, ravie, elle avait couru, saut, dans. Songez donc! des bottines, elle qui, depuis trois ans, ne pouvait pas mettre une pantoue! (Zola, Lourdes). [She had additionally, in answer to a question of Madame de Jonquire, to tell the story of the shoes that the countess had given her and with which, delighted, she had run, jumped, danced. Just think! Shoes, when for three years, she could not put on slippers!] Or: Elle, mon Dieu! elle quil avait vue pendant des annes, les jambes mortes, la face couleur de plomb [She, my God! She, whom he had seen for years with dead legs, her face the color of lead], where the writer . . . could have avoided the use of the rst person by other expressions of astonishment (like grand Dieu, for example). . . . In view of such strange cases, Mr. Ballys explanation by supposing attraction . . . seems to me insucient. . . . The narrator does not reproduce the thoughts or words of his characters in either an indirect or a direct way, . . . but he clothes them in the form which he would give to his own thoughts and words and leaves it to the reader, in fact expects it of him, that he will take them as the thoughts and words of the character and that he will understand them correctly. There is then a veiling of the factsin a certain sense a deception of the reader . . . as harmless as it is eective. . . . Such a phenomenon cannot any more be called free indirect style. . . . It is rather the style that replaces the reproduction of words and thoughts of

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

509

the character by the narrators own thoughts and speeches . . . thus veiling style or veiled discourse. Figures of Thought and Linguistic Forms by Charles Bally, University of Geneva GRM 6 (1914): 40522, 45670 In an article in this journal, I have tried to show that French has a free indirect style which has traits of ordinary indirect style and direct style. The following examples will show the similarities and the dierences existing between these three grammatical modes: Direct style: (a) Pierre dclara catgoriquement: Paul est coupable, il expiera sa faute; (b) Pierre sarrta, se demandant: Entrerai-je ou retournerai-je sur mes pas? . . . Proper indirect style: (a) Pierre dclara catgoriquement que Paul tait coupable, quil expierait sa faute; (b) Pierre sarrta, se demandant sil entrerait ou sil retournerait sur ses pas. . . . Free indirect style: (a) La dclaration de Pierre fut catgorique: Paul tait coupable, il expierait sa faute; (b) Pierre sarrta: entrerait-il ou retournerait-il sur ses pas? . . . One thing needs to be pointed out from the start: the trait common to the three styles. They are, though to dierent degrees, forms of syntax, grammatical types. In all three cases, one has the enunciation of words or thoughts attributed to a subject by a person who reports these words or these thoughts; this reporter would be Zola, for example, if the quoted sentences were drawn from one of his novels. The utterance is preceded, often also followed, and even, as we will see, mixed, penetrated, by the words written by the author. . . . The fundamental trait common to the three styles is that the narrator objectively reproduces words or thoughts without adding anything of his own; the reader has the very clear impression that the narrator (e.g., Zola) is absolutely distinct from the subject (e.g., Pierre), serves him simply as voice-carrier, without mixing his personality with that of the subject, without trying to substitute himself for him. . . . This trait of objectivity, which I thought had been established, will have to be established again. In GRM [5], Mr. Kalepky . . . gives an entirely dierent explanation of free indirect style, which he calls veiled discourse. . . . According to him, the narrator, by a kind of ction, presents the words or the thoughts of the subject as though they came from himself, that is to say that the narration in direct or indirect style is confused with the narration external to direct or indirect style but in such a manner that the reader attributes the utterance to its true author, namely, to the character. . . . We see the two essential points on which Mr. Kalepky diers

510

Poetics Today 26:3

from me: (1) the utterance is no longer objective, the narrator is no longer a simple voice-carrier; (2) it is not a matter of a grammatical form but of a gure, a gure of thought (understanding by gure a manner of conceiving and expressing a representation that does not conform to objective reality or to linguistic logic) . . . I will try to show that the indices on which Mr. Kalepky leans to prove that the author substitutes himself for his character (where I see indirect style) are formal signs without true value for the speaking subject (I); then I will oppose to them a series of other signs to which I believe that the subjects attach a value that leads to other conclusions (II); after characterizing the dierence that separates indirect style from the gure by substitution of the subject (III) and having illuminated this distinction by a parallel case (IV), I will lead from these particular facts back to general views (V and VI). I. Mr. Kalepky believes he can nd in the use of grammatical persons the indication that the narrator intervenes directly in the utterance of words or of thoughts of his character. . . . But, in all the passages quoted by Mr. Kalepky, it is a matter of exclamative and thus depersonalized expressions, like Mon Dieu! Songez donc! . . . In Zola: Elle [Sophie] dut encore . . . raconter lhistoire des bottines, des belles bottines toutes neuves, que Madame la comtesse lui avaient donns, et avec lesquelles, ravie, elle avait couru, saut, dans! Songez donc! des bottines, elle qui, depuis trois ans, ne pouvait pas mettre une pantoue! [She {Sophy} had additionally to tell the story of the shoes, the beautiful brand-new shoes that the countess had given to her and with which, delighted, she had run, jumped, danced! Just think! Shoes, when, for three years, she could not put on slippers!] Mr. Kalepky thinks that Songez donc! [Just think!], by its direct form, proves the intervention of the narrator, whereas one feels, by dierent indications that I will examine further on, that it is Sophie who speaks and that this exclamative Songez donc!, without great value of person, is an escape into pure direct style, so near to free indirect style. . . . II. Such is the value of the indices through which Mr. Kalepky thinks he can recognize the gure of substitution of the subject (veiled discourse) where free indirect style seems to me undeniable. . . . This is identical to saying that these indices are common to direct style, indirect style, and free indirect style and that the eect of them all is to show that there is an objective reproduction of utterances. (A) Indices external to the utterance: They all amount to the presence of some expression that involves a verb of thinking or saying . . . [either] preceding, inserted, or following the utterance. . . .

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

511

(B) Indices contained within the utterance: Passage to another of the three styles. The diverse styles, by following each other, mutually control each other and every wrong interpretation is excluded. . . . (C) Syntactical indicesthe tenses of the utterance: Among the traits common to the indirect style and to the free indirect style, the most striking is the transposition of the tenses of the verbs according to the rules that the usual grammar teaches. An example to illustrate this. Direct style: Il dclara catgoriquement: je veux partir, je partirai. Indirect style: Il dclara catgoriquement quil voulait partir, quil partirait. Free indirect style: Sa dclaration tait catgorique: il voulait partir, il partirait. The forms voulait and partirait are presents and indirect futures, they are transposed. But if the free indirect style is what Mr. Kalepky wants it to bea gure of thought which gives the illusion that the narrator speaks in his own namethese tenses would no longer be transposed: voulait would be a true imperfect, and partirait a present conditional; the meaning is then altogether dierent, or simply absurd. . . . (D) Syntactical indicesthe persons of the utterance: We know the transpositions that the persons of the verb undergo in the indirect style. If the narrator is designated in the utterance in the third person, can one still think that he makes believe that he is speaking in his own name, as Mr. Kalepky wishes? . . . (E) Indices identifying the subject : One can unify under this title the extremely varied facts which, though indirectly, hinder the confusion between the subject and the narrator; natural if one attributes them to the former, they are ambiguous or absurd if one attributes them to the latter, with whom they are incompatible. . . . III. Direct style, indirect style, and free indirect style belong to grammar, are syntactical types, characterized by grammatical signs (tenses, modes, persons, constructions, etc.). . . . [But we need to distinguish] between linguistic type and gure of thought. . . . What Mr. Kalepky means by the (badly chosen) term veiled discourse is like a gure of thought; but he has, I believe, not understood the nature and the limits of the phenomenon, since he includes in it the whole of free indirect style and he supports it with examples that are contrary to the idea which he holds of it. . . .2

2. Ballys article now (in the rest of vol. III and in IV, V, and VI) takes up problems of general linguistics and is no longer immediately concerned with free indirect style.

512

Poetics Today 26:3

The Stylistic Meaning of the Imperfect of Discourse (Free Indirect Style) by Eugen Lerch, University of Munich GRM 6 (1914): 47089 Ch. Bally deserves our thanks for having drawn attention in this journal to a stylistic peculiarity of French which he calls free indirect style, and Th. Kalepky has added complements that are materially and ideologically valuable.3 Thereby the purely factual understanding of the construction in question is assured. But now it is also important to point up its aesthetic signicance, which I will try to do in what follows. I will use German examples . . . all from one text: the novel Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann (45th edition, Berlin, 1909). . . . The writer of novels has three choices for expressing the speeches (or the thoughts) of his characters: (1) direct discourse, (2) indirect discourse, (3) imperfect of discourse; or, to give examples: (1) (er sagte:) Ich bin nicht zufrieden; (2) (er sagte,) er sei nicht zufrieden (or: wre nicht zufrieden); (3) er war nicht zufrieden (wie er sagte). . . . If, in case 3 (which is our concern here), the wie er sagte is omitted, what is said is formally not to be distinguished from a fact reported by the author (er war nicht zufrieden); solely the context or interspersed elements of direct speech (interjections and such like) allow us to recognize that we have read something spoken and not something that happened (e.g., Sie HATTE, strafe sie Gott, niemals eine schnere Braut gesehen, Buddenbrooks [vol.] I, [p.] 229 [She HAD, may God punish her, never seen a more beautiful bride]). . . . I must reject Ballys name of free indirect style, because it is not at all, either in French or in German, a matter of a kind of indirect style, not at all a matter of an omitted que, but rather a speech or thought presented as a fact, as the following examples will show. Now it could be supposed that what is reported as a fact is more real than what is merely said, more real than what is said in direct speech. Since indirect speech represents the least reality . . . the following scale (ordered according to mounting reality) could be expected: (1) indirect speech: er sei nicht zufrieden; (2) direct speech: Ich bin nicht zufrieden; (3) Speech as fact: er war nicht zufrieden. Only, it becomes apparent that, stylistically, direct speech (Ich bin nicht zufrieden) has a greater eect than the imperfect of discourse as fact (er war nicht zufrieden); apparently because direct speech is in the present and in the rst person, while speech as fact is merely in the past and the third person. As a result, we get a dierent scale: (1) indirect speech: er SEI nicht zufrieden; (2) speech as fact: er WAR nicht

3. Ballys article Figures of Thought and Linguistic Forms was not known to Lerch, since it appeared in the same issue of GRM.

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

513

zufrieden; (3) direct speech: Ich BIN nicht zufrieden. So the opinion that our construction represents something between direct and indirect discourse is well-founded: on the one hand, speech in the imperfect stands above direct speech . . . on the other hand, it stands below direct speech. . . . This paradoxical circumstance results in two dierent uses of our imperfect. It serves on occasion to express more than direct speech: namely, that what is reported is not merely stated but that it is really so. To give an example:

Buddenbrooks [vol.] I, [p.] 47: Aber der Konsul ging nicht erst hinber, sondern versammelte sofort die billiardlustigen Herren um sich. Sie wollen keine Partie riskieren, Vater? Nein, Lebrecht Krger BLIEB bei den Damen, aber Justus KNNE ja nach hinten gehen. [But the consul did not go over there, he immediately assembled the gentlemen desiring billiards around himself. You dont want to risk a game, father? No, Lebrecht Krger STAYED with the ladies, but Justus COULD go back.]

The knne shows that the blieb also belongs to the speech of Lebrecht Krger; but knne is in the conditional, proving that it is indirect speech, while blieb is in the indicative: apparently it is not merely speech, but at the same time reports about the fact that he really stayed with the ladies. On the other side, our imperfect can express a less, a weakening, a mufing of the direct form, an approach to the indirect form, and this is the case Bally no doubt had in mind when he spoke of free indirect style. To give an example of this case:

Buddenbrooks [vol.] II, [p.] 49: . . . und ber gerumigen Kellern erwuchs . . . Thomas Buddenbrooks neues Haus. Kein Gesprchssto in der Stadt, der anziehender gewesen wre! Es WURDE tip-top, es WURDE das schnste Haus weit und breit! GAB es etwa in Hamburg schnere? . . . MUSSTE aber auch verzweifelt teuer sein, und der alte Konsul HTTE solche Sprnge sicherlich nicht gemacht. . . . Die Nachbarn, die Brgersleute in den Giebelhusern, lagen in den Fenstern. [. . . and over roomy cellars . . . Thomas Buddenbrooks new house grew. There was no subject of conversation more attractive in the city! It BECAME tip-top, it BECAME the most beautiful house anywhere! WERE there more beautiful ones for instance in Hamburg? . . . It HAD to be terribly expensive, and the old consul would certainly not HAVE gone so far. . . . The neighbors, the inhabitants of the gabled houses, were at their windows.]

Already the word Gesprchssto suggests that what follows will provide the content of these conversations, and the word tip-top makes us certain that it is not a matter of the reections of the author, who would not

514

Poetics Today 26:3

under any circumstances use such a showy word in his epic representation; tip-top is rather, as we learned earlier, the newest fashionable word imported from Hamburg into the Lbeck world at that time; therefore it is the neighbors who make these remarks. It is clear why the author does not report these conversations in direct speech: direct speech serves in the novel to characterize the speaking person by his speech, by the construction of his sentences, by interjected favorite words or phrases, by exaggeration or avoidance; here, however, it is a matter of insignicant persons, and to characterize them would be simply useless. That is why the conversation is not given in direct speech. But why not in indirect speech? Indirect speech is no longer attractive to newer authors . . . not only in Buddenbrooks, but in the modern novel generally: it signies the appearance of a summarizing author, and the modern novel has become too dramatic for that. In its place we nd therefore the imperfect of discourse and direct speech for the expression of greater liveliness, and if our imperfect has the third person in common with indirect speech, its aliation with direct speech is more important where the stylistic value is concerned; it is more opposed than related to indirect speech. That is why I did not want to name it free indirect style, and that is why I will compare it in what follows not with indirect but with direct style. In doing so, I will try to distinguish carefully between the categories developed above of More than direct speech and Less than direct speech.. . . Let us start with Less than direct speech. To this belong, as already mentioned, the conversations of typical, colorless persons. . . . Or else, the persons are known, but their conversation is so typical and colorless that the author does not think it deserves being given in direct speech. . . . Thus when Thomas Buddenbrook addresses the question how the steamships are called that go to Copenhagen to his son, little Hanno, the direct form is not necessary, because it would have nothing that would characterize the consul in any way, and moreover, the imperfect is used to make the question into something repeated rather than something unique and special:

[vol.] II, [p.] 343: Fr Thomas Buddenbrook selbst war dieses Stck Welt am Hafen, zwischen Schien, Schuppen und Speichern, wo es nach Butter, Fischen, Wasser, Teer and geltem Eisen roch, von Klein auf der liebste und interessanteste Aufenthalt gewesen; und da Freude und Teilnahme daran sich bei seinem Sohne von selbst nicht usserten, so musste er darauf bedacht sein, sie zu wecken. . . . Wie HIESSEN nun die Dampfer, die mit Kopenhagen VERKEHRTEN? Najaden . . . Halmstadt . . . Friederike Overdieck. . . . Nun, dass du wenigstens diese weisst, mein Junge, das ist schon etwas. [For Thomas Buddenbrook himself, this piece of the world at the port, among ships, sheds, and warehouses, where it smelled of butter, sh, water, tar, and oily

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

515

iron, had been the favorite and most interesting place to stop since he was little; and since joy and participation in it did not show themselves in his son on their own, he had to think of awakening them. . . . Now how were the steamships CALLED that WENT to Copenhagen? Najaden . . . Halmstadt . . . Frederike Over-dieck. . . . Well, that you at least know these, my boy, thats something after all.]

We come to the category More than direct speech, where our imperfect simultaneously serves to represent what is said and what is really happening. The already mentioned answer of Lebrecht Krger exemplies this:

[vol.] I, [p.] 47: Sie wollen keine Partie riskieren, Vater? Nein, Lebrecht Krger blieb bei den Damen, aber Justus knne ja nach hinten gehen. [You dont want to risk a game, father? No, Lebrecht Krger stayed with the ladies, but Justus could go back.]

So does this passage:

[vol.] I, [p.] 425: Gerda aud Thomas wurden sich einig ber eine Route durch Oberitalien nach Florenz. Sie wrden etwa zwei Monate abwesend sein; unterdessen sollte Antonie . . . das hbsche kleine Haus in der Breitenstrasse bereit machen. Oh, Tony WRDE das schon zur Zufriedenheit ausfhren! Ihr sollt es vornehm haben sagte sie; und davon waren Alle berzeugt. [Gerda and Thomas agreed on a route through Northern Italy to Florence.They would be absent about two months; meanwhile Antonie was to prepare . . . the pretty little house in the Breitenstrasse. Oh, Tony WOULD accomplish this to everyones satisfaction! You will have elegant quarters she said, and everyone was convinced of this.]

Tony says that she would take care of it well, and with her love for furnishing one can be sure that she will really do it. Up until now my examples dealt with short utterances, where it seemingly did not matter very much for the characterization of the person concerned whether they were given in direct speech or in the imperfect. When the author renounces the means of characterization through direct speech in a longer passage, the imperfect becomes more conspicuous. The wonderful adventure that the young Kai Graf Mlln, the friend of little Hanno Buddenbrook, tells is, to be sure, introduced by a durfte man ihm glauben, but then the rest is given as fact throughout:

[vol.] II, [p.] 340: Und Kai fuhr fort zu erzhlen. Durfte man ihm glauben, so war er vor einiger Zeit bei schwler Nacht und in unkenntlicher Gegend einen schlpfrigen und unermesslich tiefen Abhang hinabgeglitten, an dessen Fusse er im fahlen und ackernden Schein von Irrlichtern ein schwarzes Sumpfwasser gefunden hatte, aus dem mit hohl glucksendem Gerusch unaufhrlich silberblanke Blasen aufstiegen. Eine

516

Poetics Today 26:3

aber davon, die, nahe dem Ufer, bestndig wiedergekehrt war, so oft sie zersprungen, hatte die Form eines Ringes gehabt, und diese hatte er nach langen, gefahrvollen Bemhungen mit der Hand zu erhaschen verstanden, worauf sie nicht mehr zerplatzt war, sondern sich als glatter und fester Reif hatte an den Finger stecken lassen. Er aber, der mit Recht diesem Ringe ungewhnliche Eigenschaften zugetraut hatte, war mit seiner Hilfe den steilen und schlpfrigen Abhang wieder emporgelangt. [And Kai continued to narrate. If one was to believe him, he had some time ago slid down a slippery and immeasurably deep slope in a stiing night and in an unknown region, at the foot of which he had found a black bog-water in the pale and ickering gleam of will-othe wisps, out of which silvery bubbles rose incessantly with a hollow, gurgling sound. One of them, however, which returned incessantly close to the shore, as often as it had exploded, had the form of a circle, and this he had managed to catch with his hand after long, dangerous eorts, whereupon it ceased exploding and instead let itself be put on his nger as a smooth and rm ring. But he, who had rightly attributed unusual characteristics to this ring, had with its help gone up the steep and slippery slope again.]

Of course, all this is not true, and a pedant would therefore have chosen the indirect form. . . . Thomas Mann chose the imperfect in order to represent the liveliness of the childish fantasy . . . without ironizing it. However, the author does use irony when he presents the speeches of agent Gosch in the form of facts . . . :

Herrn Gosch GING es schlecht. Mit einer schnen und grossen Armbewegung wies er die Annahme zurck, er knne zu den Glcklichen gehren. Das beschwerliche Greisenalter NAHTE heran, es WAR da, wie gesagt, seine Grube WAR geschaufelt. Er KONNTE abends kaum noch sein Glas Grog zum Munde fhren, ohne die Hlfte zu verschtten, so MACHTE der Teufel seinen Arm zittern. Da ntzte kein Fluchen. [Herr Gosch WAS badly o. With a lovely and great movement of his arm he rejected the supposition that he could belong to the happy ones. The arduousness of old age APPROACHED, it WAS present, as has been said, his pit WAS shoveled. He WAS hardly ABLE to guide his glassful of rum to his mouth without spilling half of it, to such an extent DID the devil MAKE his arm tremble. Swearing was no good.]

In this manner the author ironizes the complaints of the businessman. . . . But our imperfect is not merely used for spoken words but also for unspoken thoughts, and these examples apparently belong to the category Less than direct speech. . . .

[vol.] I, [p.] 219: Tony betrachtete die grauen Giebelhuser, die ber die Strasse gespannten llampen, das Heilige Geist-Hospital mit den fast schon entbltterten Linden davor. . . . MEIN GOTT, alles das WAR geblieben wie es gewesen war! Es HATTE hier gestanden,

Cohn

Early Discussions of Free Indirect Style

517

unabnderlich und ehrwrdig, whrend sie sich daran als einen alten, vergessenswerten Traum erinnert hatte! Diese grauen Giebel WAREN das Alte, Gewohnte, berlieferte, das sie wiederaufgenommen und in dem sie nun wieder leben sollte. Sie weinte nicht mehr; sie sah sich neugierig um. [Tony watched the gray gabled houses, the oil lamps reaching over the street, the Holy Ghost Hospital with its already almost leaess linden trees in front of it. . . . MY GOD, all this HAD remained as it had been! It HAD stood here, unchangeable and honorable, while she remembered it as a dream worthy of being forgotten! These gray gables WERE the old, the accustomed, the traditional, which had included her again and in which she was now to live again. She did not cry any more; she looked about curiously.] [vol.] II, [p.] 129: Es war nicht wahr, dass er Kopfschmerzen hatte. Er war nur mde und fhlte wieder, kaum dass der erste Morgenfriede der Nerven vorbei, diesen unbestimmten Gram auf sich lasten. . . . WARUM hatte er gelogen? WAR es nicht bestndig als htte er seinem belbenden gegenber ein schlechtes Gewissen? Warum? Warum? . . . Aber es war jetzt keine Zeit, darber nachzudenken. [It was not true that he had a headache. He was only tired and felt again, when the rst morning peace of the nerves had hardly gone away, this uncertain sorrow weigh on him. . . . WHY had he lied? WAS it not constantly as though he had a bad conscience toward his feeling bad? Why? Why? . . . But this was not the time to think about it.] 4

The author disappears almost completely. He does not reign like a god over his creatures, he does not surpass them in intelligence, he is in no sense omniscient. . . . Even where he is apparently not in agreement with his characters, he does not indicate this with a single syllable. . . . Our imperfect of speech and thought is thus a part of the retreat of the author, his surrender, his absorption in his characters, which critics have called (I dont know why) cold and heartless: the direct form will not do in all places, and the indirect form would mean a stepping back of the characters and a stepping forward of the author that is avoided for good reasons in the modern novel. More and more it is replaced by the imperfect of discourse that thus can be seen in a larger frame: it is related to progress of narrative technique.

4. I have chosen two out of an unusual profusion of examples given by Lerch for the use of the imperfect for expressing unspoken thoughts.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- BigPond - Why Emotional DifferentDocument9 pagesBigPond - Why Emotional DifferentAhmad Razzak100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- L'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film ClassicsDocument35 pagesL'Année Dernière À Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad) BFI Film Classicsgrão-de-bico100% (5)

- Hesiod-Hesiod - Volume I, Theogony. Works and Days. Testimonia (Loeb Classical Library No. 57N) - Loeb Classical Library (2006) PDFDocument195 pagesHesiod-Hesiod - Volume I, Theogony. Works and Days. Testimonia (Loeb Classical Library No. 57N) - Loeb Classical Library (2006) PDFJosé Amável100% (9)

- 7 DLL HOPE 3 2019-2020 JulyDocument2 pages7 DLL HOPE 3 2019-2020 JulyCelia BautistaNo ratings yet

- Ict and Social ResponsibilityDocument23 pagesIct and Social ResponsibilityMaria Flor Pabelonia100% (1)

- Planet Jockey Level Four John DespainDocument5 pagesPlanet Jockey Level Four John Despainapi-538759367No ratings yet

- Ardis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07Document29 pagesArdis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Clayton, 'Time Passes' Virginia Woolf's Virgilian Passage A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu and To The Lighthouse 2006Document34 pagesClayton, 'Time Passes' Virginia Woolf's Virgilian Passage A La Recherche Du Temps Perdu and To The Lighthouse 2006lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Gabrieloni, Ecfrasis. Ekphrasis, 08 PDFDocument14 pagesGabrieloni, Ecfrasis. Ekphrasis, 08 PDFlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Fry, Postimpressionism 1912Document12 pagesFry, Postimpressionism 1912lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Georg Simmel, Strangeness, and The StrangerDocument3 pagesGeorg Simmel, Strangeness, and The Strangerlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Guy Maddin InterviewedDocument3 pagesGuy Maddin Interviewedlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Rancière, Why Emma Bovary Had To Be KilledDocument16 pagesRancière, Why Emma Bovary Had To Be Killedlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Ardis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07Document29 pagesArdis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Jones, T. E. Hulme, Wilhelm Worringer and The Urge To Abstraction 60Document7 pagesJones, T. E. Hulme, Wilhelm Worringer and The Urge To Abstraction 60lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Aldington, The Art or Poetry 1923 PDFDocument12 pagesAldington, The Art or Poetry 1923 PDFlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Heffernan, Staging Absorption and Transmuting The Everyday A Response To Michael Fried 08Document17 pagesHeffernan, Staging Absorption and Transmuting The Everyday A Response To Michael Fried 08lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Jones, T. E. Hulme, Wilhelm Worringer and The Urge To Abstraction 60Document7 pagesJones, T. E. Hulme, Wilhelm Worringer and The Urge To Abstraction 60lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Bishop, Reverdy 'S Conception of Image 10Document12 pagesBishop, Reverdy 'S Conception of Image 10lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Volinsky, Wrtings On Dance in Russia 20sDocument351 pagesVolinsky, Wrtings On Dance in Russia 20slily briscoe100% (4)

- Ford Madox Ford, The Soul of LondonDocument198 pagesFord Madox Ford, The Soul of Londonlily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Fry, Postimpressionism 1912Document12 pagesFry, Postimpressionism 1912lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Flesh Eating TechnologiesDocument3 pagesFlesh Eating Technologieslily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Ferguson, Poetic Responses To Grande Jatte 01Document15 pagesFerguson, Poetic Responses To Grande Jatte 01lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Ardis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07Document29 pagesArdis, The Dialogics of Modernism(s) in The New Age 07lily briscoeNo ratings yet

- TS Eliot Poetry and Drama 1950Document45 pagesTS Eliot Poetry and Drama 1950StanojkaKrupnikovicNo ratings yet

- Mayakovsky - PoemsDocument273 pagesMayakovsky - Poemslily briscoeNo ratings yet

- Fried, Three PoemsDocument3 pagesFried, Three Poemslily briscoeNo ratings yet

- DLL Ni TotoyDocument21 pagesDLL Ni TotoyWinston YutaNo ratings yet

- Module 4.... FinalDocument3 pagesModule 4.... FinalChristian Cabarles FeriaNo ratings yet

- SEPS Plan of Action for Academic Year 2020-2021Document3 pagesSEPS Plan of Action for Academic Year 2020-2021Mark Rednall MiguelNo ratings yet

- Conduct of Learning Action Cell: Ray Harvey L. DominiceDocument19 pagesConduct of Learning Action Cell: Ray Harvey L. DominiceKeycie Gomia - PerezNo ratings yet

- Etech WK1Document4 pagesEtech WK1RonaNo ratings yet

- Final SlideDocument16 pagesFinal SlideHow to give a killer PresentationNo ratings yet

- Global Media Cultures For PresentationDocument13 pagesGlobal Media Cultures For PresentationDianne Mae LlantoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Technology in Delivering Curriculum: Andro Brendo R. Villapando Maed - PeDocument43 pagesThe Role of Technology in Delivering Curriculum: Andro Brendo R. Villapando Maed - PeNorman C. CalaloNo ratings yet

- Professional Communications Presentations GuideDocument20 pagesProfessional Communications Presentations GuideUpekha Van de BonaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Move Analysis of Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesTopic: Move Analysis of Literature Reviewsafder aliNo ratings yet

- Product AdvertisingDocument7 pagesProduct AdvertisingSalvador RamirezNo ratings yet

- Ten Things Every Microsoft Word User Should KnowDocument10 pagesTen Things Every Microsoft Word User Should KnowHossein Mamaghanian100% (1)

- E-Learning in English Language Teaching and LearningDocument24 pagesE-Learning in English Language Teaching and LearningAlmhaNo ratings yet

- Self-Learning Module Science3Document13 pagesSelf-Learning Module Science3Torres, Emery D.No ratings yet

- Use Cases Description of Blood Bank Project - T4TutorialsDocument8 pagesUse Cases Description of Blood Bank Project - T4TutorialsNathaniel Van PeebleNo ratings yet

- Oral Mediation Practice 2 - Candidate A - Bicycle SafetyDocument2 pagesOral Mediation Practice 2 - Candidate A - Bicycle SafetyandreablesaNo ratings yet

- Asia Through Geography RubricDocument1 pageAsia Through Geography Rubricapi-450445489No ratings yet

- LP - Co1Document7 pagesLP - Co1jeraldin julatonNo ratings yet

- MKT 233 - Mother MurphysDocument12 pagesMKT 233 - Mother Murphysapi-302016339No ratings yet

- Proposar Car Free WritingDocument29 pagesProposar Car Free WritingWayan GandiNo ratings yet

- ASHRAE Social Media GuidelinesDocument72 pagesASHRAE Social Media GuidelinesAbdalsalam AlhajNo ratings yet

- Open Source Intelligence Investigation GuideDocument1 pageOpen Source Intelligence Investigation GuidesamirNo ratings yet

- Santana Et Al How To Practice Person Centred CareDocument12 pagesSantana Et Al How To Practice Person Centred CareShita DewiNo ratings yet

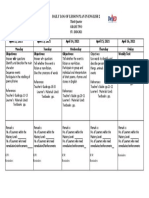

- Daily Log of Lesson Plan in English 2Document1 pageDaily Log of Lesson Plan in English 2Jesusima Bayeta AlbiaNo ratings yet

- TCC - KEYNET Optical ManagerDocument2 pagesTCC - KEYNET Optical ManagerSergioNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Intro. To Media and Info. Literacy 1.1Document5 pagesChapter 1 Intro. To Media and Info. Literacy 1.1Rasec Nayr CoseNo ratings yet