Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pay Dividends and Repurchase Stock (8524)

Uploaded by

asif_iqbal84Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pay Dividends and Repurchase Stock (8524)

Uploaded by

asif_iqbal84Copyright:

Available Formats

PAY DIVIDENDS AND REPURCHASE STOCK

A companys dividend is set by the board of directors. The announcement of the dividend states the payment will be made to all stockholders who are registered on a particular record date. Then a week or so later dividend checks are mailed to stockholders. Stocks are normally bought or sold with dividend (or cum- dividend) until two business days before the record date, and then they trade exdividend. If you buy stock on the ex-dividend date, your purchase will not be entered on the companys books before the record date and you will not be entitled to the dividend. The company is not free to declare whatever dividend it chooses. In some countries, such as Brazil and Chile, companies are obliged by law to pay out a minimum proportion of their earnings. Some restrictions may be imposed by lenders, who are concerned that excessive dividend payments would not leave enough in the kitty to repay their loans. In the United States, state law also helps to protect the firms creditors against excessive dividend out of legal capital, which is generally defined as the par value of outstanding shares. Most U.S companies pay a regular cash dividend each quarter, but occasionally this is supplemented by a one-off extra or special dividend. Many companies offer shareholders automatic dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs). Often the new shares are issued at a 5% discount from the market price. Sometimes 10% or more of total dividends will be reinvested under such plans. Dividends are not always in the form of cash. Frequently companies also declare stock dividends. For example, if the firm pays a stock dividend of 5%, it sends each shareholder 5 extra shares for every 100 shares currently owned. A stock dividend is essentially the same as a stock split. Both increase the number of shares but do not affect the companys assets, profits, or total value. So, both reduce value per share. The Dividend Decision is a decision made by the directors of a company. It relates to the amount and timing of any cash payments made to the company's stockholders. The decision is an important one for the firm as it may influence its capital structure and stock price. In addition, the decision may determine the amount of taxation that stockholders pay. There are three main factors that may influence a firm's dividend decision: Free-cash flow Dividend clienteles Information signaling

The free cash flow theory of dividends

Under this theory, the dividend decision is very simple. The firm simply pays out, as dividends, any cash that is surplus after it invests in all available positive net present value projects.

A key criticism of this theory is that it does not explain the observed dividend policies of real-world companies. Most companies pay relatively consistent dividends from one year to the next and managers tend to prefer to pay a steadily increasing dividend rather than paying a dividend that fluctuates dramatically from one year to the next. These criticisms have led to the development of other models that seek to explain the dividend decision.

Dividend clienteles

A particular pattern of dividend payments may suit one type of stock holder more than another; this is sometimes called the clientele effect. A retiree may prefer to invest in a firm that provides a consistently high dividend yield, whereas a person with a high income from employment may prefer to avoid dividends due to their high marginal tax rate on income. If clienteles exist for particular patterns of dividend payments, a firm may be able to maximise its stock price and minimise its cost of capital by catering to a particular clientele. This model may help to explain the relatively consistent dividend policies followed by most listed companies.'

A key criticism of the idea of dividend clienteles is that investors do not need to rely upon the firm to provide the pattern of cash flows that they desire. An investor who would like to receive some cash from their investment always has the option of selling a portion of their holding. This argument is even more cogent in recent times, with the advent of very low-cost discount stockbrokers. It remains possible that there are taxation-based clienteles for certain types of dividend policies.

Information signaling

A model developed by Merton Miller and Kevin Rock in 1985 suggests that dividend announcements convey information to investors regarding the firm's future prospects. Many earlier studies had shown that stock prices tend to increase when an increase in dividends is announced and tend to decrease when a decrease or omission is announced. Miller and Rock pointed out that this is likely due to the information content of dividends.

When investors have incomplete information about the firm (perhaps due to opaque accounting practices) they will look for other information that may provide a clue as to the firm's future prospects. Managers have more information than investors about the firm, and such information may inform their dividend decisions. When managers lack confidence in the firm's ability to generate

cash flows in the future they may keep dividends constant, or possibly even reduce the amount of dividends paid out. Conversely, managers that have access to information that indicates very good future prospects for the firm (e.g. a full order book) are more likely to increase dividends. According to Grullon (2002) the information value lies in the fact that a dividend increase signals a decrease in systematic risk (a decrease in discount rate), the correlation between dividend changes and earnings changes has not been proved.

Investors can use this knowledge about managers' behaviour to inform their decision to buy or sell the firm's stock, bidding the price up in the case of a positive dividend surprise, or selling it down when dividends do not meet expectations. This, in turn, may influence the dividend decision as managers know that stock holders closely watch dividend announcements looking for good or bad news. As managers tend to avoid sending a negative signal to the market about the future prospects of their firm, this also tends to lead to a dividend policy of a steady, gradually increasing payment. In a fully informed, efficient market with no taxes and no transaction costs, the free cash flow model of the dividend decision would prevail and firms would simply pay as a dividend any excess cash available. The observed behaviours of firm differs markedly from such a pattern. Most firms pay a dividend that is relatively constant over time. This pattern of behavior is likely explained by the existence of clienteles for certain dividend policies and the information effects of announcements of changes to dividends.

REPURCHASE STOCK

A program by which a company buys back its own shares from the marketplace, reducing the number of outstanding shares. Share repurchase is usually an indication that the company's management thinks the shares are undervalued. The company can buy shares directly from the market or offer its shareholder the option to tender their shares directly to the company at a fixed price. Because a share repurchase reduces the number of shares outstanding (i.e. supply), it increases earnings per share and tends to elevate the market value of the remaining shares. When a company does repurchase shares, it will usually say something along the lines of, "We find no better investment than our own company." Instead of paying a dividend to its stockholders, the firm can use the cash to repurchase stock. The reacquired shares may be kept in the companys treasury and resold if the company needs money. There are four main ways to repurchase stock. By far the most common method is for the firm to announce that it plans to buy its stock in the open market, just like any other investor.

However, companies sometimes use a tender offer where they offer to buy back a stated number of shares at a fixed price, which is typically set at about 20% above the current market level. Shareholders can then choose whether to accept this offer. A third procedure is to employ a Dutch auction. In this case the firm states a series of prices at which it is prepared to repurchase stock. Shareholders submit offers declaring how many shares they wish to sell at each price and the company calculates the lowest price at which it can buy the desired number of shares. Finally, repurchase may take place by direct negotiation with a major shareholder. The most notorious instances are greenmail transactions, in which the target of an attempted takeover buys off the hostile bidder by repurchasing any shares that it has acquired. Greenmail means that these shares are repurchased at a price that makes the bidder happy to leave the target alone. This price does not always make the targets shareholders happy. Stock repurchases, like dividends, are a way to hand cash back to shareholders. But unlike dividends, share repurchases are frequently a one-off event. So a company that announces a repurchase program is not making a long-term commitment to earn and distribute more cash. The information in the announcement of a share repurchase program is therefore likely to be different from the information in a dividend payment. Companies repurchase shares when they have accumulated more cash than they can invest profitably or when they wish to increase their debt levels. Neither circumstance is good news in itself, but shareholders are frequently relieved to see companies paying out the excess cash rather than frittering it away on unprofitable investments. Shareholders also know that firms with large quantities of debt to service are less likely to squander cash. Stock repurchases may also be used to signal a managers confidence in the future. When companies offer to repurchase their stock at a premium, senior management and directors usually commit to hold on to their stock. So it is not surprising that researchers have found that announcements of offers to buy back shares above the market price have prompted a larger rise in the stock price.

You might also like

- #Assignment #2 HRM CompleteDocument41 pages#Assignment #2 HRM Completeasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Coca Cola Internship ReportDocument307 pagesCoca Cola Internship Reportasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Measures of Relationship (Stats)Document1 pageMeasures of Relationship (Stats)asif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Coca Cola Internship ReportDocument307 pagesCoca Cola Internship Reportasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Measures of Relationship (Stats)Document1 pageMeasures of Relationship (Stats)asif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Internship Report On FojifertilizerDocument179 pagesInternship Report On Fojifertilizerasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Assisgment#2 Cost AccountingDocument2 pagesAssisgment#2 Cost Accountingasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Internship Report Finance On ICI Paints PakistanDocument144 pagesInternship Report Finance On ICI Paints Pakistanasif_iqbal84100% (1)

- Asian Development Bank (8523)Document1 pageAsian Development Bank (8523)asif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Risk Aversion (8522)Document6 pagesRisk Aversion (8522)asif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Production and Operations ManagementDocument3 pagesProduction and Operations Managementasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Assisgment#2 Cost AccountingDocument2 pagesAssisgment#2 Cost Accountingasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- The Disadvantages of A Periodic Inventory SystemDocument4 pagesThe Disadvantages of A Periodic Inventory Systemasif_iqbal84100% (1)

- Internship Report Finance On ICI Paints PakistanDocument144 pagesInternship Report Finance On ICI Paints Pakistanasif_iqbal84100% (1)

- Assisgment#2 Cost AccountingDocument2 pagesAssisgment#2 Cost Accountingasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- As IfDocument1 pageAs Ifasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Market Research Statistical TechniqueDocument4 pagesMarket Research Statistical Techniqueasif_iqbal84100% (1)

- Trading OrganizationDocument29 pagesTrading Organizationasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- Internship Report On ZTBL by Mumtaz Ali HulioDocument48 pagesInternship Report On ZTBL by Mumtaz Ali Hulioasif_iqbal84No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Methodology Statement - MicropilingDocument5 pagesMethodology Statement - MicropilingRakesh ReddyNo ratings yet

- Sale Agreement SampleDocument4 pagesSale Agreement SampleAbdul Malik67% (3)

- AmulDocument4 pagesAmulR BNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs SimilarDocument7 pagesUnit 6 Lesson 3 Congruent Vs Similar012 Ni Putu Devi AgustinaNo ratings yet

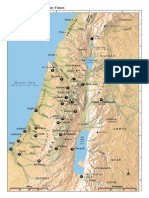

- Israel Bible MapDocument1 pageIsrael Bible MapMoses_JakkalaNo ratings yet

- #1 HR Software in Sudan-Khartoum-Omdurman-Nyala-Port-Sudan - HR System - HR Company - HR SolutionDocument9 pages#1 HR Software in Sudan-Khartoum-Omdurman-Nyala-Port-Sudan - HR System - HR Company - HR SolutionHishamNo ratings yet

- Powerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterDocument24 pagesPowerpoint Lectures For Principles of Macroeconomics, 9E by Karl E. Case, Ray C. Fair & Sharon M. OsterJiya Nitric AcidNo ratings yet

- Farm Policy Options ChecklistDocument2 pagesFarm Policy Options ChecklistJoEllyn AndersonNo ratings yet

- Underground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaDocument6 pagesUnderground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaAnonymous LyxcVoNo ratings yet

- 3 QDocument2 pages3 QJerahmeel CuevasNo ratings yet

- Teacher swap agreement for family reasonsDocument4 pagesTeacher swap agreement for family reasonsKimber LeeNo ratings yet

- EDMOTO 4th TopicDocument24 pagesEDMOTO 4th TopicAngel Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- (Section-A / Aip) : Delhi Public School GandhinagarDocument2 pages(Section-A / Aip) : Delhi Public School GandhinagarVvs SadanNo ratings yet

- (Click Here) : Watch All Paid Porn Sites For FreeDocument16 pages(Click Here) : Watch All Paid Porn Sites For Freexboxlivecode2011No ratings yet

- 14 Worst Breakfast FoodsDocument31 pages14 Worst Breakfast Foodscora4eva5699100% (1)

- Erp Software Internship Report of Union GroupDocument66 pagesErp Software Internship Report of Union GroupMOHAMMAD MOHSINNo ratings yet

- Sale of GoodsDocument41 pagesSale of GoodsKellyNo ratings yet

- HLT42707 Certificate IV in Aromatherapy: Packaging RulesDocument2 pagesHLT42707 Certificate IV in Aromatherapy: Packaging RulesNilamdeen Mohamed ZamilNo ratings yet

- Product Life CycleDocument9 pagesProduct Life CycleDeepti ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Revision Summary - Rainbow's End by Jane Harrison PDFDocument47 pagesRevision Summary - Rainbow's End by Jane Harrison PDFchris100% (3)

- FORM 20-F: United States Securities and Exchange CommissionDocument219 pagesFORM 20-F: United States Securities and Exchange Commissionaggmeghantarwal9No ratings yet

- Hospitality Marketing Management PDFDocument642 pagesHospitality Marketing Management PDFMuhamad Armawaddin100% (6)

- Protein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDocument2 pagesProtein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDale HardingNo ratings yet

- Food and ReligionDocument8 pagesFood and ReligionAniket ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- BrianmayDocument4 pagesBrianmayapi-284933758No ratings yet

- Math 8 1 - 31Document29 pagesMath 8 1 - 31Emvie Loyd Pagunsan-ItableNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Unit 3bDocument2 pagesIntermediate Unit 3bgallipateroNo ratings yet

- Research Course Outline For Resarch Methodology Fall 2011 (MBA)Document3 pagesResearch Course Outline For Resarch Methodology Fall 2011 (MBA)mudassarramzanNo ratings yet

- Corporate Office Design GuideDocument23 pagesCorporate Office Design GuideAshfaque SalzNo ratings yet

- PORT DEVELOPMENT in MALAYSIADocument25 pagesPORT DEVELOPMENT in MALAYSIAShhkyn MnNo ratings yet