Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Agency Digests

Uploaded by

amazing_pinoyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Agency Digests

Uploaded by

amazing_pinoyCopyright:

Available Formats

Keeler Co. (PLAITIFF) v. Rodriguez (DEF) Facts: Keeler Co.

. was a company engaged in the electrical business and the sale of a product called a Matthews Electric Plant. An A.C. Montelibano approached Keeler offering to find purchasers for the said product. Keeler told him that there would be a 10% commission for him for any plant that he could sell. Montelibano offered the product to DEF. DEF bought the product. Without the knowledge of Keeler Co. however, DEF paid the purchase price to Montelibano (P2,531.55). In the trial, it was established that Keeler Co. never received any part of the price paid. As a result, plaintiff commenced this action against the DEF. Lower court ruled in favor of DEF hence this appeal. Issue: WON DEF's obligation was discharged by its payment to Montelibano? Held: No. Lower court judgment is reversed. Ratio: Art. 1162 CC: Payment must be made to the persons in whose favor the obligation is constituted, or to another authorized to receive it in his name. The testimony is conclusive that the plaintiff never authorized Montelibano to receive or receipt for money in behalf of Keeler Co., and that the defendant had no right to assume by any act or deed of the plaintiff that Montelibano was authorized to receive the money, and that the defendant made the payment at his own risk and on the sole representations of Montelibano that he was authorized to receipt for the money. Rules (Mechem, Agency) as cited by SC: An assumption of authority to act as agent for another of itself challenges inquiry. Like a railroad crossing, it should be in itself a sign of danger and suggest the duty to "stop, look, and listen." It is therefore declared to be a fundamental rule, never to be lost sight of and not easily to be overestimated, that persons dealing with an assumed agent, whether the assumed agency be a general or special one, are bound at their peril, if they would hold the principal, to ascertain not only the fact of the agency but the nature and extent of the authority, and in case either is controverted, the burden of proof is upon them to establish it. The person dealing with the agent must also act with ordinary prudence and reasonable diligence. Obviously, if he knows or has good reason to believe that the agent is exceeding his authority, he cannot claim protection. So if the suggestions of probable limitations be of such a clear and reasonable quality, or if the character assumed by the agent is of such a suspicious or unreasonable nature, or if the authority which he seeks to exercise is of such an unusual or improbable character, as would suffice to put an ordinarily prudent man upon his guard, the party dealing with him may not shut his eyes to the real state of the case, but should either refuse to deal with the agent at all, or should ascertain from the principal the true condition of affairs. And not only must the person dealing with the agent ascertain the existence of the conditions, but he must also, as in other cases, be able to trace the source of his reliance to some word or act of the principal himself if the latter is to be held responsible.

Rallos v. Yangco (1911, Moreland) Doctrine: Having advertised the fact that Collantes was his agent and having given them a special invitation to deal with such agent, it was the duty of the defendant on the termination of the relationship of principal and agent to give due and timely notice thereof to the plaintiffs. Failing to do so, he is responsible to them for whatever goods may have been in good faith and without negligence sent to the agent without knowledge, actual or constructive, of the termination of such relationship.

Yangco sent Rallos a letter on November 1907 stating that he was opening an office where he would be selling tobacco and offering to do business with Rallos. The letter included the arrangements as to the comission rates, etc, and in the final paragraph, Yangco indicated that Mr. Collantes was his agent and that he had conferred public power of attorney to the latter, "to perform in my name and on my behalf all acts necessary for carrying out my plans ... Mr. Collantes will sign by power of attorney, so I beg that you make due note of his signature hereto affixed."

Rallos then decided to do business with Yangco through Collantes by sending him produce to be sold on commission. Later, on February 1909, Rallos again sent to Collantes, as agent for Yangco, 218 bundles of tobacco in the leaf, again to be sold on commission: it was sold for P1744 thus the sale charges were P206.96; however, the remaining P1537.08 which should have been delivered to Rallos was not given to them. "This sum was, apparently, converted to his own use by said agent."

It appears that Yangco had already severred the agency with Collantes prior to the sending of tobacco; hence, the latter was no longer acting as his factor at the time. "This fact was not known to the plaintiffs, and it is conceded in the case that no notice of any kind was given by the defendant to the plaintiffs of the termination of the relations". Yangco refused to pay the amount being demanded by Rallos, stating that Collantes was no longer acting as his agent but on his own personal capacity. Hence, this suit. Issue: Can Rallos recover from Yangco? Held: Yes. Collantes was previously introduced to Rallos as Yangco's agent, thus it was his duty, upon termination of the relationship of principal and agent, to give notice to Rallos. "Failing to do so, he is responsible to them for whatever goods may have been in good faith and without negligence sent to the agent without knowledge, actual or constructive, of the termination of such relationship."

JIMENEZ V RABOT (Street, 1918) Facts Petitioner Gregorio Jimenez owned three parcels of land situated in Alaminos, Pangasinan. While petitioner was staying at Vigan Ilocos, his property in Alaminos was confided by him to the care of his elder sister Nicolasa Jimenez. He later wrote a letter to his sister informing the latter that he was pressed for money and requested her to sell one his parcels of land and send him the money in order that he might pay his debts. However, the said letter contains no description of the land to be sold other than is indicated in the words one of my parcels of land. Acting upon this letter, petitioners sister sold the said parcel of land for P500 to defendant Pedro Rabot. But there was no evidence that she sent any of the proceeds to her brother. A year later, petitioner demanded that his sister should surrender the said parcels of land to him, including that sold to the defendant, but she refused. As a result, petitioner filed an action in the CFI for the purpose of recovering the parcels of land. Issue : W/N the authority conferred on petitioners sister by the letter sent by Jiminez was sufficient to enable her to bind her brother as to the sale of the parcel of land to defendant Rabot? YES, the authority to sell is sufficient and Jimenez could not recover. Held/Ratio: 1. Under the law (A.1713 old civil code and Sec.335 code of civil procedure), the authority to alienate land shall be contained in an express mandate and that the authority of the agent must be in writing and subscribed by the party to be charged. The Court is of the opinion that the authority expressed in the said letter is a sufficient compliance with both requirements. 2. Jimenez argument: The authorization must contain a particular description of the property which the agent is to be permitted to sell. And because the letter only indicated one of my parcels of land, such indication is not a sufficient description as to make the authorization binding upon the principal.

SC: Specific description of property is unnecessary . It is sufficient if the authority is so expressed as to determine without doubt the limits of the agents authority. The specific description of the property is only required to the sufficiency of the contract of sale (remember, one of the essential elements of a contract is that the object must be determinate or at least determinable) and not to the sufficiency of the authorization.

Katigbak v. Tai Hing Co. (Villareal, 1928) Doctrine:

The power is general and authorizes Gabino to sell any kind of realty belonging to the principal. The use of the subjunctive pertenezcan (might belong) and not the indicative pertenecen (belong), means that Po Tecsi meant not only the property he had at the time of the execution of the power, but also such as he might afterwards have during the time it was in force Facts:

Gabino Barreto Po Ejap was the owner of the subject land which was subjected to a mortgage lien in favor of PNB to secure payment of P60 000 with 7% interest per annum

Po Tecsi, executed a general power of attorney in favor of his brother Gabino Barreto Po Ejap, authorizing him to perform on his behalf and as lawful agent to buy, sell or barter, assign or admit in acquittance, or in any other manner to acquire or convey all sorts of property, real and personal, businesses and industries, credits, rights and action belonging to me, for whatever prices and under the conditions which he may stipulate, paying and receiving payment in cash or in installments, and to execute the proper instruments with the formalities provided by law.

12/1921: Po Tecsi executed an instrument acknowledging an indebtedness to his brother Gabino P68 000, the price of the properties which Gabino had sold to him

03/1923: Gabino executed a 2

nd

mortgage on the subject land in favor of Antonio Limjenco for the sum of P140 000

04/1923: Gabino sold the said land to Po Tecsi for P10 000, subject to the same encumbrances

11/1923: Gabino, using the power conferred on him by Po Tecsi, absolutely sold the land to Jose Katigbak for P10 000 mentioning the mortgage lien of P60 000 in favor of PNB, without recording his power of attorney or the sale in the proper certificate of title. Po Tecsi remained in possession

10/1924: Po Tecsi leased a part of said land to Uy Chia for 5 years

08/1924: Po Tecsi wrote Gabino complaining that he had been after him for the forwarding of the rents of the property, explaining his precarious financial condition, telling him that he did not collect the rents for himself, and promising to remit the balance after having paid all expenses of repairs and cleaning up

11/1925: Po Tecsi told Gabino that if he wanted to lease the property in question to SmithBell, he should consult Po Tecsi first

Mortgage in favor of Limjenco was cancelled.

11/1926: Po Tecsi died. Po Sun Suy (Po Tecsis son) submitted to Gabino a liquidation of accounts showing the rents collected on the property

02/1927: Po Sun Suy was appointed administrator of the estate of his deceased father, submitting an inventory including the land in question as one of the properties left by his father and obtaining the TCT in his name as administrator. He wrote his uncle Gabino begging him to let him pay the rent later

Gabino assigned all his rights and actions in the credit of P68 000 against Po Tecsi to his son Po Sun Boo

05/1927: Katigbak sold the property in question to Po Sun Boo for P10 000

Ever since the property had been sold by Gabino to Katigbak, Gabino had administrated it, entering into an oral contract of lease with Po Tecsi, who occupied it at monthly rental of P1500. When Po Tecsi died, P Sun Suy, as administrator of the estate of Po Tecsi, continued renting the landon which Po Chings store stood

An action was brought in CFI Manila for the recovery of said rent amounting to P45 280, first against Tai Hing Co., and later against members of firm (Po Sun Suy and Po Ching)

Po Sun Suy as judicial administrator of Po Tecsis estate, filed an intervention praying that a judgment be rendered against Katigbak declaring him not to be the owner of the property in question hence, not entitled to the rents Issue:

1.

Who is the owner of the land in question? Katigbak Ratio:

Po Sun Suy: Gabino was not authorized under the power executed by Po Tecsi to sell the land.

SC: The power is general and authorizes Gabino to sell any kind of realty belonging to the principal. The use of the subjunctive pertenezcan (might belong) and not the indicative pertenecen (belong), means that Po Tecsi meant not only the property he had at the time of the execution of the power, but also such as he might afterwards have during the time it was in force

While a power of attorney not recorded in the registry of deeds is ineffective in order that an agent or attorney-in-fact may validly perform acts in the name of his principal, and that any act performed by the agent by virtue of said power with respect to the land is ineffective against a third person who, in good faith, may have acquired a right thereto, it does, however, bind the principal to acknowledge the acts performed by his attorney-in-fact regarding said property

While non-registration of the power of attorney prevents the sale made in favor of Katigbak from being recorded in the registry of deeds, it is not ineffective to compel Tecsi to acknowledge said sale.

Po Tecsis promises to send and remit the rents to Gabino were a tacit acknowledgment that he occupied the land no longer as an owner but only as lessee.

Sale made by Gabino, as attorney-in-fact of Po Tecsi, in favor of Katigbak is valid. After said sale, Po Tecsi leased the property sold from Gabino who administered it in Katigbaks name. Katigbak sold the property to Po Sun Boo

DANON V ANTONIO A. BRIMO & CO. (Johnson, 1921) Plaintiff broker Defendant principal Doctrine: The duty assumed by the broker is to bring the minds of the buyer and seller to an agreement for a sale, and the price and terms on which it is to be made, and until that is done his right to commissions does not accrue. Facts Defendant company, through its manager Antonio Brimo, employed the plaintiff to look for a purchaser of defendants factory for a sum of P1.2M payable in cash. The defendant promised to pay to the plaintiff, as compensation for his services, a commission of 5% on the said sum of P1.2M if the sale was consummated, or if the plaintiff should find a purchaser ready, able and willing to buy said factory for P1.2M. However, it is important to note that another broker, Sellner, was also negotiating the sale, or trying to find a purchaser for the same property and that the plaintiff was informed of that fact either by Brimo himself or by someone else; at least, it is probable that the plaintiff was aware that he was not alone in the field. Subsequently, plaintiff went to see Mauro Prieto, president of Santa Ana Oil Mill, and offered to sell to him the defendants factory at P1.2M. Prieto instruct ed his manager to see Antonio Brimo to get permission from him to inspect the premises. Prietos manager made a favorable report to Prieto who then asked for an appointment with Brimo to perfect the negotiation. In the meantime, Sellner had found a purchaser for the same factory, who ultimately bought it for P1.3M. For that reason Prieto, the would-be purchaser found by the plaintiff, never came to see Antonio Brimo to perfect the proposed negotiation. Hence, plaintiff brought an action to recover the P60K commission which he believes he is entitled to receive for his services as a broker. Issue: W/N plaintiff had performed all that was required of him under his contract with defendant to entitle him to recover the 5% commission agreed upon? NO! Holding The most that can be said as to what the plaintiff had accomplished is, that he had found a purchaser who might have bought the defendants factory if the defendant had not sold it to someone else. The evidence does not show that the Santa Ana Oil Mill had definitely decided to buy the factory at the fixed price of P1.2M. Also the board of directors of Santa Ana had not resolved to purchase said factory. Moreover, the undertaking to procure a purchaser requires of the agent, not simply to name or introduce a person who may be willing to make any sort of contract in reference to the property, but to produce a party capable, and who ultimately becomes the purchaser. This, the plaintiff failed to accomplish. Under the circumstances of the case, it is perfectly clear and undisputed that plaintiffs services did not in any way contribute towards bringing about the sale of the factory in question. In other words, he was not the efficient agent or the procuring cause of the sale. Therefore, plaintiff is not entitled to the 5% commission. Ratio The duty assumed by the broker is to bring the minds of the buyer and seller to an agreement for a sale, and the price and terms on which it is to be made, and until that is done his right to commissions does not accrue. It follows that a broker is never entitled to commissions for unsuccessful efforts. The risk of failure is wholly his. The reward comes only with his success. This doctrine however must be taken with one important and necessary limitation. If the efforts of the broker are rendered a failure by (1) the fault of the employer if capriciously he changes his mind after the purchaser, ready and willing, and consenting to the prescribed terms, is produced; or (2) if the purchaser declines to complete the contract because of some defect of title in the ownership of the seller, then the broker does not lose his commission.

You might also like

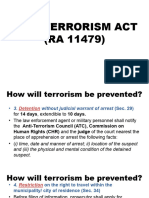

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 4Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 4amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- JR 2 RRDDocument3 pagesJR 2 RRDamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 2Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 2amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 5Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 5amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Military Justice System Part 3Document6 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 3amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Planner Cover PageDocument1 pagePlanner Cover Pageamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Military Justice System Part 2Document7 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 2amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- DOJ CIRCULAR 20 Dated 31 Mar 2023Document11 pagesDOJ CIRCULAR 20 Dated 31 Mar 2023amazing_pinoy0% (1)

- Anti-Terrorism Act Part 3Document4 pagesAnti-Terrorism Act Part 3amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Ra 7055Document2 pagesRa 7055zrewtNo ratings yet

- Military Justice System Part 4Document5 pagesMilitary Justice System Part 4amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Language RoutineDocument1 pageLanguage Routineamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- NLRC Notice On PICOPDocument11 pagesNLRC Notice On PICOPamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Fully Booked Reading ChallengeDocument1 pageFully Booked Reading Challengeamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Annex B - AffidavitDocument1 pageAnnex B - Affidavitamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Philippines Map ChartDocument1 pagePhilippines Map Chartamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Blue Sands AttireDocument1 pageBlue Sands Attireamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Philippine Government Agencies Directory 2022Document293 pagesPhilippine Government Agencies Directory 2022amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- INTERVIEW QUESTIONS (INCIDENT+IQ) - Ebanking Channels - FT, Bills Payment, Cardless WithdrawalDocument2 pagesINTERVIEW QUESTIONS (INCIDENT+IQ) - Ebanking Channels - FT, Bills Payment, Cardless Withdrawalamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Approved Revised Transaction Dispute Form 062618 PDFDocument2 pagesApproved Revised Transaction Dispute Form 062618 PDFGersonCallejaNo ratings yet

- Mnemonic Phrase "Every Good Boy Does FineDocument1 pageMnemonic Phrase "Every Good Boy Does Fineamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Filings and Procedures at the Office of the City ProsecutorDocument7 pagesFilings and Procedures at the Office of the City Prosecutoramazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

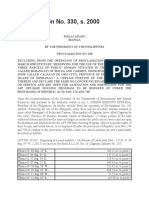

- PP 330Document2 pagesPP 330amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence on Estafa by MisappropriationDocument241 pagesJurisprudence on Estafa by Misappropriationamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Motion To Release Firearm SampleDocument2 pagesMotion To Release Firearm Sampleamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Professor's Final Class Explores Life and LegacyDocument25 pagesPhilosophy Professor's Final Class Explores Life and Legacyamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Coon of Tax Appeals: Second DivisionDocument3 pagesCoon of Tax Appeals: Second Divisionamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Ra 10121Document23 pagesRa 10121amazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- JuneDocument21 pagesJuneamazing_pinoyNo ratings yet

- Jus PXUh Poc 4 SQD CCme 7 S1616851512Document6 pagesJus PXUh Poc 4 SQD CCme 7 S1616851512ALAKA RAJEEV 1930317No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sherrod Swayvon - Brief in Support of Motion To Suppress or in The Alternative For An Evidentiary Hearing Terry Stop - FinalDocument7 pagesSherrod Swayvon - Brief in Support of Motion To Suppress or in The Alternative For An Evidentiary Hearing Terry Stop - Finalapi-266438930No ratings yet

- Jane Doe v. Choice Hotels - Sex Trafficking LawsuitDocument17 pagesJane Doe v. Choice Hotels - Sex Trafficking LawsuitMichael LindenbergerNo ratings yet

- California UCC-1 StatementDocument5 pagesCalifornia UCC-1 StatementJered T. Ede100% (2)

- Action For Reconveyance and Annulment of Title June 22Document3 pagesAction For Reconveyance and Annulment of Title June 22Nikko Echegorin100% (1)

- Case Toh Huat Khay V Lim A ChangDocument22 pagesCase Toh Huat Khay V Lim A ChangIqram Meon100% (1)

- (G.R. No. 224679, February 12, 2020) Jonah Mallari Y Samar, Petitioner, V. People of The Philippines, Respondent. Decision Leonen, J.Document12 pages(G.R. No. 224679, February 12, 2020) Jonah Mallari Y Samar, Petitioner, V. People of The Philippines, Respondent. Decision Leonen, J.yeniiliciousNo ratings yet

- Arguments Advanced - RespondentDocument3 pagesArguments Advanced - RespondentAayush AroraNo ratings yet

- Legal Services Agreement for Stock TransferDocument2 pagesLegal Services Agreement for Stock TransferZendy PastoralNo ratings yet

- Guevarra v. EalaDocument3 pagesGuevarra v. EalaPatrick Anthony Llasus-NafarreteNo ratings yet

- Undertaking For Provisional PracticeDocument3 pagesUndertaking For Provisional PracticeAnkush Verma100% (1)

- Prison Reforms PDFDocument20 pagesPrison Reforms PDFAnkitTiwariNo ratings yet

- Tinsley V Flanagan AZ DES Class Action Complaint 2015Document51 pagesTinsley V Flanagan AZ DES Class Action Complaint 2015Rick Thoma0% (1)

- JANI Arbitration CommitmentDocument4 pagesJANI Arbitration Commitmentaziz moniesson s.No ratings yet

- Legal Writing Case Digests Set 3 PFR Edited PDFDocument37 pagesLegal Writing Case Digests Set 3 PFR Edited PDFLynett Jorolan JadulosNo ratings yet

- The Great DebatersDocument3 pagesThe Great DebatersSellaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Theory Second Edition A Concise Anthology PDFDocument2 pagesEthical Theory Second Edition A Concise Anthology PDFBrendaNo ratings yet

- Gaite v. FonacierDocument2 pagesGaite v. FonacierAngelette BulacanNo ratings yet

- Fulfilment of DutyDocument2 pagesFulfilment of DutyJohn Rey FerarenNo ratings yet

- PAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMDocument5 pagesPAUL LEE TAN vs. PAUL SYCIP and MERRITTO LIMRal CaldiNo ratings yet

- Notes On Double SalesDocument2 pagesNotes On Double SalesVanessa SanchezNo ratings yet

- Prac Court - 8 CasesDocument13 pagesPrac Court - 8 CasesLotus KingNo ratings yet

- Should parents be legally responsible for their children's actsDocument4 pagesShould parents be legally responsible for their children's actsJithNo ratings yet

- Mock Test Taker 2018 ExodusDocument25 pagesMock Test Taker 2018 ExodusAnonymous KSedwANo ratings yet

- S Urana & S Urana N Ational T Rial A Dvocacy M Oot C Ourt C Ompetition 2016Document29 pagesS Urana & S Urana N Ational T Rial A Dvocacy M Oot C Ourt C Ompetition 2016akshi100% (1)

- Kimberly-Clark Worldwide v. Naty ABDocument5 pagesKimberly-Clark Worldwide v. Naty ABPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Lekas v. United Airlines Inc, 4th Cir. (2002)Document9 pagesLekas v. United Airlines Inc, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- GEK 1012 Contemporary Social Issues in SingaporeDocument5 pagesGEK 1012 Contemporary Social Issues in SingaporeAizhenLimNo ratings yet

- Philippine Airlines vs Court of Appeals on Suspension of Claims Against Corporation Under RehabilitationDocument2 pagesPhilippine Airlines vs Court of Appeals on Suspension of Claims Against Corporation Under RehabilitationLindsay MillsNo ratings yet

- What Is The Effect of Non-Use of Corporate Charter of A Corporation? Sec. 22Document5 pagesWhat Is The Effect of Non-Use of Corporate Charter of A Corporation? Sec. 22ronaldNo ratings yet

- Sources of International LawDocument6 pagesSources of International Lawmoropant tambe0% (1)