Professional Documents

Culture Documents

H. D. None, 'Settlements and Welfare of The Ple-Temiar Senoi of The Perak-Kelantan Watershed'

Uploaded by

ben_geo100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

324 views61 pagesNoone's 1936 account of the Temiars (Malaysia), the only substantial publication he produced on them. This important study has been very hard to get hold of. (This version does not include the detailed map attached to the original.)

Original Title

H. D. None, 'Settlements and Welfare of the Ple-Temiar Senoi of the Perak-Kelantan Watershed'

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentNoone's 1936 account of the Temiars (Malaysia), the only substantial publication he produced on them. This important study has been very hard to get hold of. (This version does not include the detailed map attached to the original.)

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

324 views61 pagesH. D. None, 'Settlements and Welfare of The Ple-Temiar Senoi of The Perak-Kelantan Watershed'

Uploaded by

ben_geoNoone's 1936 account of the Temiars (Malaysia), the only substantial publication he produced on them. This important study has been very hard to get hold of. (This version does not include the detailed map attached to the original.)

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 61

Part I

""'N- V .,-- ,,- 0"-

.... .t , j' . ". 5!NGAPORE"

CONTENTS.

Preface_

1. Culture, Breed and Language among Malayan

Aborigines

2. Summary of Previous Records

Part II 1. An Outline of the Perak-Kelantan water-

shed: and the expeditions

Part III

2. The Breed and Culture of the PIe-Temiar

Senoi

3. Demography: the Ple-Temiar population

CONTACTS

1. The Temiar and the Forests

2. The Temiar and Cultivation

3. The Temiar and Wild Life

4. The Temiar and Health.

5. Temiar Trade and Enterprise

6. The Temiar and Culture Contact

Part IV PROPOSED ABORIGINAL POLICY

1. Present circumstances affecting the Status

of the Temiar

2. The Scheme of a Controlled Reservation and

Pattern SettlemeI!ts

3. Summary of Provisions necessary in propos<!d

Enactment

4. Conclusion

Page 1

4

10

21

33

40

41

43

44

46

51

61

62

67

73

Appendices I, II, III. IV. V, VI

\.

PREFACE.

Half a century of pioneer work umong the aborigines of the

Peninsula has prepared a setting in which it is profitable, in the

north at any rate, to describe each group intensively according to

modern functional methods. Skeat and Blagden'sl classical study on

the pagan races ' provided a basic survey compiled from many sources

from which it appeared that there were broadly speaking three

aboriginal "complexes," the woolly-haired nomads of the north and

north-east, predominantly Negritos; the straight-haired, "proto-

Malay" jungle dwellers of the south, usually termed Jakun; and in the

centre the wavy-haired Senoi or "Sakai." Mr. I. H. N. Evans and

Pater Schebesta have more recently described the northern Negrito

groups in some detail: the ethnographical survey of the south has

advanced little since Skeat' s time, and so for the past three or four

years the present writer has concentrated upon the Senoi of the

main range of the peninsula. The results of this research will be

published in succeeding numbers of this joumal. The present number

is intended to clear the ground for the presentation of these facts

and to supply the geographical setting. Some two years ago the

writer was invited to make a report to Government on the welfare

and distribution of the northem Senoi who inhabit the mountains

between Perak and Kelantan, and Lv discuss policies of reservation.

The second half of this number is based therefore upon this Report,

and a succinct account of the breed and culture of the Temiar Senoi

naturally finds its place as a basis for any discussion bearing on

aboriginal policy. A demographic survey of the territory follows

logically upon the account of their environment, and a preliminary

statement of evidence bearing upon the population is included here,

as affecting the problems with which Government is faced. A more

detailed analysis of vital statistics will accompany the .second part

of the monograph, which will deal with the sociology of the Temiar.

So soon as the physical and observations made on the

living .subjects in the field have been worked out statistically by a

specialist in physical anthropolog"'j a subsequent number will be

devoted entirely to their breed. Their language, material culture,

magico-religious beliefs and mythology will also be dealt with fully.

Investigations of such an intensive nature could never have been

carried out but for the courtesy of the Government of Perak in

according me the opportunity and facilities for the work.

1 Pagall Raus of tlw lIfa.lay Penin81tla, Volumes I and H. W. W. Skeat and

C. O. Blagden. Macmillan & Co., London, 1906.

Journ. F. M. S. Mus. - Vol. XIX.

Frontispiece.

HILL TEMIAR DANCING THE "KANANYAR",

PART I.

CUL TURE, BREED AND LANGUAGE.

The aboriginal races of the Malay Peninsula are generally

known locally as "Sakai." An inclusive name for the various tribes is

desirable, and "Sakai," having become fashionable, will serve the

purpose best. Yet it is important to clear up many misapp:'ehensions

about the use of this term.

The first is one of scientific terminology. Unfortunately, earl?

investigators in the Peninsula, following Annandale, restricted the

scope of the term .. Sakai" applying it only to the wavy-haired Senoi

tribes of the main range of the Peninsula. Dr. Rudolf Martin and

Mr. 1. H. N. Evans alone stood out against this practice, which has

caused confusion locally, well-read people using the term in variance

of vernacular usage. Pater Schebesta, who has done so much to

record accurately the proper names of the nomadic Negrito tribes,

(on the principle of adopting their own word for" fellow man"

followed by the tribal name perhaps originally applied by neighbours)

has given sanction to this restricted use of "Sakai" which still

persists in -the literature of comparative anthropology. I propose to

accept the popular local usage of .. Sakai" as a general term, and to

substitute" Senoi" for the wavy-haired people.

Certain groups of Negrito nomads in Upper Perak and elsewhere

in the north certainly fell into almost complete economic dependence

on Malays; but the mere fact that these groups were distinguished

as " hamba," whilst the neighbouring hill tribes were not, shews that

the term .. Sakai" does not necessarily imply dependence.

It will be apparent from the above argument that .. Sakai"

must include a variety of peoples. It is essential to realise this

qualification when using the term, which can only be a convenient

but approximate label. These tribeR may be classified from three

points of view. On the linguistic side the nomad collectors alone

furnish us with six dialects: and the Senoi and Jakun contribute

about six more. Generalisations, for example, about extent of

"Sakai" vocabulary and "Sakai" numeral systems frequently quoted,

have little meaning. At least two dialects have numeral systems up .

to ten and the statement that all " Sakai" cannot count above three

is incorrect.

From the point of view of physical type, alt}1Ough it is convenient

to speak of three main groups, anthropometric analysis and observa-

tion shew that there is probably no group which is homogeneous, and

the fact is that at least four racial types, if not more, can be

distinguished among the "Sakai," and at most we can only speak

of anyone group being predomirw.ntl?j N e ~ i t o or predominantly

2

Journal of tke F.M.S. Museums

[VOL. XIX,

Proto-Malay. The Australo-Melanesoid type, for instance! occurs

occasionally among all groups. It is impossible to be dogmatic a?out

the average stature of the "Sakai." One element is. comparabvely

tall, individuals of five feet nine inches or more occurnng.

We are left therefore with the third consideration, that .of the

mode of life. There is, once again, no such thing as a

II Sakai" culture .. There are tribes who are, practically speakiDg,

nomad collectors: others who plant catch crops and build a temporary

village of flimsy little houses: yet who make

settlements in long-houses on the higher ranges and rotate their

plantations on the hill slopes around: one group plants

wet padi, owns buffaloe.'l, yet speaks a non-Malay dialect.

The mode of life is the most consistent basis fur classification:

the physical types are too scattered.

The most primitive mode of life in the is of

the nomadic "collectors." These are a senes of tnbes hvmg

mainly in the north. but penetrating far south in isolated groups

into Pahang on the east of the Peninsula. These peoples are

predominantly Negritos. though other elements are present. Perhaps

the historical fact is that the" collecting" mode of life has been the

principal means of survival of the purer Negrito type, for where

Negritoid types are found following other modes of life they .the

results of intermarriage. The Malays and also the otheraborlgme3

who possess a higher (material) culture recognise these tribes under

the deprecatory names of Semang (Kedah), Pangan (Kelantan,

Trengganu, North Pahang), .. Orang Liar," .. Orang Belukar" and so

forth. Thanks to the researches of Mr.!. H. N. Evans and Pater

Schebesta these are the best known aborigines.

A higher mode of life is that characterised by the planting of

catch crops, and the building of more permanent

diet is largely dependent on trapping and the blowpipe. This IS

perhaps the most widely spread mode of life, and is followed by the

predominantly wavy-haired lowland Semai Senoi in South Perak and

North-west Pahang, and also the Proto-Malay Jakun of Johore, South

Pahang and Negri Sembilan.

Perhaps the most formidable group are the Temiar or Northern

Senoi who inhabit the main range from Gunong Noring, south to

Cameron Highlands. They possess a typical hill culture, live in long

houses (of early Indonesian type) and practise a much modified shift-

ing cultivation, planting up successive plots on the hill slopes around.

Many groups remain seven or eight years in one spot. They maIn-

tained their independence of the Malays, even before the British

regime. This hill culture extends down among the hill Semai: it is

associated with a predominantly Indonesian (Nesiot) physical type, in

many ways the finest aboriginal stock in the peninsula. Yet the down

river Temiar, though to a less extent than among the Semai, do not

exhibit this intensive cultivation and the large houses, and are predo-

minantly of more primitive racial stocks called for the present the

II older strata."

1936] Culture, Breed and Language 3

On the eastern slopes of Benom, chie.fly on the Sungei Krau,

(but also to the south on the Kerdau, and probably in the U1u Tekai

and Ulu Remaman), are the enigmatical Jah Chong, whose mode of

life is similar to the Malays. They plant "sawah" (wet padi): somp

groups own buffalos and like many other Indonesians practise circum-

cision without regarding this rite as an initiation to Islam. Yet they

speak a language of their own. They appear to be a fair mixture of

wavy-haired (Indonesian) and straight-haired Proto-Malay, but they

occasionally intermarry with the elusive Negrito nomads whom they

call "Kleb" or "Orang Liar." Perhaps we should add the mode of life

of the "Orang Laut," predominantly Proto-Malay sea gypsies, whose

only dwellings are their boats and whose livelihood is mainly fishing.

Though these interesting peoples arc found all around the coasts of

Malaysia from Mergui to Celebes under the name of Orang Manfang,

Orang Bajau, etc., very f.ew persist in this mode of life along

the coasts of the peninsula. Reports of their movements would be

valuable.

It is important to lay stress on these diversities because they

seem to be unobtrusive. There is, of course, a highest common

factor for all the groups, but this is lower than a superficial study

would lead one to think. On the whole they tend to live in the jungle,

though some make clearings extensive enough to be able to speak of"

II going intL the jungle" when they pass from one settlement to the

other. They do not profess any of the world religions to any extent.

They rely mostly on their environment for the major needs of life.

Their allegiances are for the most part local. and their loyalties are

to the group: yet outside these limits their feeling of "community"

as expressed in their language may be far wider, though not always

prepotent.

. When we are concerned with any particular group, we find the

mterplay of all three elements, the language, the" organisation" or

mode of life, and the breed of men. Speech is a mode of social

behaviour: without the medium of speech human society in its known

forms would be impossible. The language a particular group speaks

holds it apart from groups speaking other tongues, whilst community

of speech breeds intercourse. The composition of the breed of a

particular people follows on this intercourse through intermarriage.

the Senoi and the northern Negrito groups, physically

disparate, meet, they learn each others language and the offsnring of

the hybrid marriages join the mother's group. In the south two

neighbouring groups whose breed is almost identical do not know

each others language and speak Malay when they meet, and the

offspring of mixed marriages join the group of the father.

Speech and culture are most often interdependent: breed is more

dispersed. 'When groups possessing a common culture distinguish

their fellows as "senoi" in Conrad's sense of "one of us" and refer to

strangers of different culture and alier; tongue as "gob" or "stranger,"

their community of feeling is reflected in their language and so

plainly has common limits with that language. Yet some of their

"fellows" may be physical types also represented in the "stranger"

group. In so far as no group is homogeneow') in breed the motive force

4 Journal of the F.M.S. Museums [VOL. XIX,

behind the organisation of separatt! groups is prepotently cultural,

and the language is the most assertive expression of this fact.

Many tribes indulge in external trade, washing tin and tapping

jelutong, whilst most groups collect rattans for sale. Some earn

salaries as elephant drivers, others as labourers for felling on estates,

whilst on Cameron Highlands some !lave settled down to permanent

occupation on one estate.

Such statements as "the simple Sakai" or "these most pathetic

of people" are entirely elliptical. The word "Sakai" in fact is only

useful provided one remembers it means very little: it covers as we

have seen at least four types of culture, twelve dialects and four or

five racial types. A common error is to select some trait which

characterisel" one particular group, tram;port it in "cold storage" and

make it one element in some mythical assemblage of unrelated traits

for which "Sakai" is too often a label. And, in fact "Sakai"

comes to mean .i ust what you want it to mean: if you are a missionary

the Sakai 'is an unsociable, simple, unclean creature who cannot count

above three: if you are a conservator of game the Sakai is not so

simple: he suddenly assumes a terrifying lethal Quality. If you are

a Malay who has his eye on a choice "dusun" planted UP by these

you teU the District Officer how the "Sakai" are "here to-day and

gone If you are a writer of fiction the is invari-

ably "cowering in his flimsy shelter scratching his lupus skin as he

grows old."

There is, however, one indisputable fact, namely the lack of

easily availahle systematic knowledge about the aborigines: and it has

not been possible therefore, for a cohtrent aboriginal policy to develop.

The first step then is to avoid reading too specific a meaning into the

term "Sakai" and to build up separate intensive studies of the rather

diverse patterns of culture and breed to be understood under that

term. An attempt is here made to present vital facts about the

Temiar Senoi, a hill people of the main range between Perak and

Kelantan .

PREVIOUS RECORDS.

rr II faut continuer, if ne faut pas recommencer."

Two works published in the years 1905 and 1906 placed the study

of the Pagan Tribes on a systematic basis: Dr. Rudolf Martin's book

l

was chiefly anthropological, whilst that of W. W. Skeat and Dr.

C. O. Blagden2 was a compilation of all that was known about the

ethnology, magico-religious beliefs and material culture of the variou:-3

tribes.

Both books contain exhaustive surveys of earlier accounts, so

that in the present insta nce I shall only trace the significant advances

in our knowledge of the Senoi tribes on the main range. It is worth

bearing in mind however that earlier explorers recognised only one

non-Malay aboriginal element in the 'Peninsula, and the tribes were

1 Die Inlandstamme der Malay ischen Halbinsel. verlag Gustav Fischer.

Jena, 1905. I .

2 Pagan Races of the Mala'll Pen;w.rn/(! . Sl<e!lt & .

P1'eVtOUS Records 5

described as differing merely in terms of the degree of intermixtm'e

between this single . aboriginal strain and the more recent Malay

intruders. Thus we have the" Pan-Negrito" theory of de Quatre-

fagesl, Vaughan Stevens, de la Croix and de Morgan: whilst Miklu-

cho-Maclay2 that the aboriginal element was Melanesian'

and he spoke of Melano-Malays and Malays. Clifford, however,

before 1894 had promulgated the idea of a separate wavy-haired

element, and from vocabularies he collected on the Plus and the Jelai

divided this element into two tribes, the more northerly of which he

called Tembe and the more southerly, the Senoi3. Skeat

4

as early

as 1902 distinguished three aboriginal elements woolly-haired

Negrito, lank-haired Jakun and wavy-hair-ed which last

designated the element along the main range described by Clifford.

In 1903, Annandale and Robinson

5

published the results of their

investigations among the Negritos and also the wavy-haired peof.)le

behind Temengor and in the Batang Padang; though

they did not suggest any solution of the racial affinities of the latter

element which they readily distinguished from the Negritos. Later

however Annanda1e

G

described them as " dwarf Mongolians" a 'most

interesting identification which was not to be developed until quite

recently.

It was left to Rudolf Martin

7

the great German doyen of physical

anthropology, to investigate scientifically this wavy-haired element

which he termed" Senoi ." He discounted Pater Schmidt'sS associa-

tion of them with certain tribes of Frnch Indo-China wh.ich had been

based largely evidenCE: at second-hand. He compares

thE-m rather With certalll Jungle tribes of southern India termed

"Pre-Dravidian" by Richards, and the Veddas of Ceylon and the

Toalas of Celebes which Sarasin

9

also maintained were evidence of a

Veddo.id subs tratum in South-eastern Asia. Virchow

10

though rather

tentatively, had also put forward this view.

Skeat and Blagdenll rather inclined to this Pre-Dravidian classi-

which linked the. S.enoi, whom they distinguished as Sakai ,

al.so With the more DraVidian -element among the Australian abori-

gllles. in the of comparative anthropology.

the S.enOi a processIOn of terminology (Pre-Dravidian,

DravI.do-Australoid, Proto-Australoid and Vedd-Australoid)

which empha,)Ised more and more strongly this affinity. Blagden

1 The Pigmies, de Quatrefages . Journ. R.A .S., S.B., Nos. 11 and 13

2 Ethn?lo!l,ical E xcursions . Journ. R.A.S., S.B., No.2. .

3 Sakal DUllects of the Malay Peninsula. J01lm. R.A.S., S .B., No. 24.

4 Joum. Royal Anth1'opologi cul Institute, vol. XXXII, 1902. "Wild Tribes

of the Malay Peninsula."

6 Fasciculi Malay enses. Pa rt I, Anthropology. London, 1903.

6 Malay Mail, December 22nd, 1904.

7 Die Inlandstamme der Malay ischen Halhinsel.. Jena 1905

8 Die Sprachen der Sakai und Semang auf Malukka, lh; Verhaltnis zu

den M?n-Khmer Sprachen. Bijdragcn tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde van

N.-Indle, (1901).

9 Versuch einer Anthropolog';e der [nsel Celebes. Thiel II. F. & P. Sarasin.

10 Verhandlungen de" Be"liner Gesellschaft fur Anhropologie. XXvIII.

11 Pagan Races of the Mala.y Peninsula.

Journal of the F M.s. MuseumS

[VOL. xIx,

also demonstrated more clearly from linguistic evidence the. reality

of an aboriginal peninsular Malay element in the south WhICh pre

1 " I"

dated the historical intrusion of the more comp ex orang me ayu

or "Deutero-Malays" from Sumatra.

To the Northern and Central tribes of Senoi defined by Clifford.

Sk-eat and Blagden tentatively addl'd Southern (Besisi in Selangor

and Northern Negri Sembilan) and Eastern (on the Benom

massif in Pahang). They retained the earlier term "Sakai"

f(lr these wavy-haired tribes. Dr. Blagden compiled from many

sources a comparative vocabulary of all the aboriginal dialects and

while he developed1 the theme of their linguistic affinities with the

Mon-Khmer dialects, referring to the Austro-Asiatic branch of the

great Austric family of human languages he insisted on the evidence

for Indonesian elements in these dialects as well.

Wilkinson2 publi'shed a more complete vocabulary of Central Senoi

collected from a Gopeng aborigine. He also wrote a short account

of the pagan tribes, and this appears in slightly different form in

the beginning of his "History of the Peninsular Malays" and in a

chapter forming part of a compilation "Twentieth Century Impres-

sions of British Malaya."3 Wilkinson presents us with some inter-

esting information about the Northern Senoi.4 These. are

as differing in many respects from the other pagan trIbes; as hvmg

in long communal houses, going in for more intensive cultivati?n,

and being more formidable and hostile to strangers, and so bemg

feared by their n-eighbours. Annandale

5

had previously noted that

non-Negritc hill-men ("Po-KIo") in Ulu Temengor, now included by

Wilkinson as "Northern Senoi" were economically independent of the

Malays and did not hold friendly intercourse with them. Whatever

his SOUi'ces. Wilkinson's description of the Northern Senoi has stooo

the test of ' recent research.

Circumstances prevented Mr. I. H. N. Evans from intensive

study of anyone group over a sufficiently long period. A long series

of papers, most of which have been collected in his two books,S

chieflv add valuable new information on the beliefs and customs of

the Negrito tribes. He also paid several visits to the Central Senoi

but only on two expeditions did he touch the Northern Senoi. once

in Ulu Temengor

7

and once on the Korbu and in Ulu Kinta.

s

He

bears out Wilkinson's record of the formidability of this Northern

1 Also earlier in 1894, Early Indo-Chinese influence in the Malay Peninsula_

JOUrt!.. R.A.s., S.B., No. 27.

2 Wilkinson's A Vocabulary of Central Sakai: The Aboriginal Tribes :

History of the Peninsular Malays all in "Papers on Malay Subjects."

3 Edited by Arnold Wright. Lloyd's G. B. Publishing Co., 1908.

4 "Northern Sakai or Senoi"=Ple-Temiar Senoi=Orang Bukit (Malay).

"Central Saka'i or Senoi"=Semai Senoi=Orang or Mai Darat (Malay).

Wilkinson, like Skeat and Schebesta, retained the restricted use of the

term "SakaL"

6 Fasciculi Malayenses. Part 1. Anthropology, p. 24.

6 Religion, FolJv.lore and Custom in N. Borneo and the Malay Penilumla ..

Cambridge, 1923 and Papers on the Ethnology and Archaeology of the. Malay

Peninsula. Cambridge, 1927.

7 Upper Perak Aborigines. Jour1l . F.M.S. Museums, Vol. VI. 1915-1916.

8 Notes on the Sakai of the Korbu River and of the Ulu Kinta. Journ.

F M .S. Museu1ns, Vol. VII, 1917.

'

1936] Prevtous Records

hill tribe, but so much does he regard them as a hybrid tribe that he

calls them the "Negrito-Sakai" in Temengor. He repudiates the

orthodox Vedd-Australoid affinity of the Senoi and inclines rather to

the view put forward by Schmidt that these wavy-hair'2d people are

related racially to tribes in Southern French Indo-China.

Pater Schebesta spent two years in the peninsula and

was the first since Martin to have the opportunity to study one of

the aboriginal groups intensively. He d2voted most of his time to

the Negritosl but undertook two expeditions across the main range

among the wavy-haired hill people.

2

After deliberation, but in my

opinion for inadequate reasons, he allowed the locally indiscriminate

term "Sakai" to persist instead of "Senoi," adopted by Rudolf Martin,

and frequently though not consistently employed by Evans.

But he was the first to record the correct tribal name for the

"Central Sakai," namely Semai. The "Northern Sakai" he calls the

.. Ple-Temiar." But there is no' question of there being two triJ::.es,

"Ple" in Perak and "Temiar" in Kelantan. Actually "PIe" is the

Negrito term for these Northern hillmen and is adopted by the groups

adjacent to them, whilst "Temiar" or "Tem3r" is the Semai term for

them and is adopted in areas adjacent to them, as in Pahang, Ulu

Nenggiri and in the Ulu Kinta, Perak. Semai or "S-3man," moreover.

is the Temiar term which these southern hill people have adopted

from their northern neighbours. The tribal terminology is mutually

applicable.

On Schebesta's first expedition through Ple-Temiar territory, he

approached from the Negrito area he had h3en studying and his

route was up the Temengor, an area where Negrito contacts are

considerable. He spent a fortnight with a group near Kuala Jemheng

and collected materials foOr a grammatical sketch of their language:

he then crossed by the Lanweng into the VIu Panes, a tributary vf

the Yai, and so past Kuala Prias into t1:3 Nenggiri. His second

expedition was through the Semai groups of the Batang Padang in

Perak, and across into the Ulu Bertam, so following the Telom down-

stream t{) the Jelai. This route it will be noticed, once it crosses

into Pahang, follows just south of the Temiar boundary.

He devotes a few chapters of his second book "Orang Utan" of

which an English translation is not yet available, to the people he

met during these two expeditions. His account of the Ple-Temia,

sh-ews strong Negrito influence on beliefs and he describes them as

"a large mixed tribe." I do not think that Schebesta's investigation

among the Ple-Temiar or Semai can claim such solid authority as

his truly intensive work among the Negrito groups. As th3 map

accompanying this report shews, his path lay not through the bulk

of out-{)f-contact Temiar territory until he was into the Yai and his

fortnight of intensive study was spent in the Temengor; and it is

by no means admissible to regard a single journey in jungle hills of

this nature as supplying a representative picture of a1\ aspects of the

local breed and culture. For example, the total number of Temiar

I "Among the Forest Dwa,rfs of Malaya."

2 Orang Utan. P. P. Schebesta, Brockhaus. 1928 and a series of papers

published in Festschrift P. W. Schmidt. "Anthropos" and other periodicals.

journal of the F M.S. Museums [YOLo

measured by h;m is only thirty. Nevertheless, the account he gives

demonstrates the advantages of the methods of a trained obse:vei

over the unorganised impressions of the ordinary traveller, glven

the same brief period of contact with a people.

He was impressed, for with

of manv individuals he encountered \11 the hills; he mentIOns this tWice

in his 'published work, though he does not. define any. such type in

his analysis of aboriginal racial -8lements In the Penmsula.!

The researches of Schebesta first indicate that one aboriginal

strain (Australoid) which characterises the "Sakai" also occurs

occasionally among all groups. His definition of a "Pre-Mongoloid"

j vpe also among these wavy-haired people, and his Polynesian imprE-s-

stress the fact that in no group, not even all "Negrito" groups,

can culture and be two entities linked together to form a

discrete tribal unit.

My own intensive work, while it may impose a doubt on thl"

reality of the Mongoloid element in the terms in which Schebesta

casts it and while it may suggest a closer definition for the element

which impressed him as "Polynesian," confirms the main point of

Schebesta's heterogeneous analysis.

The Present InvestiJ!.ation.

My expeditions were of two kinds. It was first necessary to

study the pattern of the culture, and for this work I resided

for two periods of three and four months With smgle local groups

in the Ulu Brok Kelantan and the Ulu Plus, Perak. It was then

necessary to plot the distribution of settlements and of the various

physical and cultural traits .. For this purpose several

were made both west to east across the watershed, and from souta

to north along its slopes. Throughout the series of expedi-

tions no permanent staff of carriers was retained, the 02X-

pedition recruiting bearers at the local settlements, many of

whom had never worked for any motive beyond their own immediate

food-quest before. This greatly reduced expense, and it meant

meeting the inhabitants with no traditional prestige on which to

cling, but rather as man to man. The permanent field staff consisted

solely of a kamoong Malay as cook-boy and a Tcmiar as

messenger: whilst the Museum collector. Inche Yeop Ahmat,

accompanied me whenever fresh ground was broken in order to mak0

a contact traverse of the route taken.

The expedition camped in various ways according to the

circumstances; sometimES in patrol tents, sometimes under hastily

constructed lean-to shelters; sometimes under the lee of limestone rock

shelters; whilst for long- residence with any group a bamboo and atap

hut was built.

The cont.act map of the Perak-Kelantan watershed which

illustrates this paper could not have been made but for the goodwill

and co-operation of the Survey Department, who loaned instruments

:tnd from the first have suffered gladly an amateur at their craft.

I Anthropological measurements in Senwngand Sakai in Malaya by P. R.

Schebest a and V. Lehzelter (Anthropologie Prague VI, 1928) .

The Present investigation

The actual mapping depended on time and compass travtlses of the

routes taken, and bearings, hill-sketching, and clinometric readings

from convenient summits. This was carried out by Inche Yeop

Ahmat, Perak Museum Collector, who was formerly in the Topo-

graphical Surveys.

The map has been built up mainly through the spare-time efforts

of Captain G. H. Sworder of the Survey Department, who

throughout coached the Collector and gave every encouragement. for

the work. It is certain that but for the correlations Captain Swordcr

worked out with earlier bearings, many of them thirty years old, the

map would not have attained the coherence it possesses. It could

not, however, have been produced at all had not the Surveyor-General,

agreed to have it mounted and printed at the Map Office,

Kuala Lumpur.

Much of the territory of the PleTemiar lies outside Perak.

Throughout the expeditions the Governments of Kelantan and Pahang

have done everything in their power to help me. It would be difficult

to express sufficient gratitude to those friends, officials and unofficials,

on both sides of the range whose houses were the first I reached after

crossing the watershed ..

Many unnecessary hardships were added to the expeditions by thl!

propaganda of a very few irresponsible Malays who resented the

presence of somebody who wanted to see the aborigines at first hand.

Twice misrepresentations of this sort, which reached groups not yet

known to me, nearly caused disaster. Such incidents however were

more than compensated for by the co-operation of the Government

penghulus; and the untiring loyalty of my own Malay field staff.

Th'lse .vho remain with me have seen seven to eight months in the

jungle each year over a period of four and a half years.

10 journal 0/ the F.M.S. Museums

PART II.

OUTLINE OF THE TOPOGRAPHY OF THE

PERAK-KELANTAN WATERSHED.

[VOL. XIX,

The amazing developments during the last quarter of a century

in Malaya have left few areas which may still be regarded as

unexplored. During the last three years, it has been my privilege to

traverse in many directions, and also to reside in one of the few

remaining blanks on the map. The story of the pioneer discoveries

in Malaya is described by Sir Hugh Clifford in one of his most .

absorbing books" Further India." But it was Sir Hugh Clifford who

on another occasion referred to the untouched aboriginal block of

Malayan territory which more or less was centred on the main range

of the Peninsula, though it extended in the east to include the Tahan

range and in the south the Benom range. To-day we find that the

Gap road and its branches has cut across to Kuala Lipis in the

south: the East Coast Railway now blazes a steel trail between the

middle part of the main range and Gunong Tahan; whilst just to the

south of the heart of the main range, the Batang Padang road cuts

half across the mountains to reach the vortex of Cameron Highlands.

Yet .we may note that the northern half of Clifford's "Aboriginal

Malaya," that which lies between Cameron Highlands and Gunong

Noring, has remained undisturbed to this day. Small roads, like the

roads to Lasah and Jalong from Sungei Siput, have, it is true, touched

the fringes of this country on the west, but otherwise we face a

territory of jungle hills nearly the size of the state of Selangor.

This territory corresponds with the distribution of an aboriginal

tribe called the PIe-Temiar Senoi: from Cameron Highlands south to

the boundary of Negri Sembilan live their cousins the Semai SenoL

On the west the "one inch to one mile" Topo-Survey maps "frame"

the Divide up as far north as the latitude of Grik: on the east the

remoteness of Ulu Kelantan has not yet been surveyed on this scale.

Four expeditions have left us some information about the

northern half of the main range. In 1888, Mr. C. F. Bozzolo, then

Collector of the District of Upper Perak, followed up the Plus and

then its tributary the lVIenlik and so got across into the DIu Betis.

In 1905, Mr. J. N. Sheffield took a Survey party up the Plus as far as

the Kernam, whence he struck into the DIu Piah and so after arduous

work succeeded in placing a survey beacon on Gunong Grah and

taking readings from the summit. Later, Major W. A. D. Edwards

reached Gunong Noring in the Ulu Sengoh. In 1923, Pater Schebesta,

the ethnologist, followed up the Temengor and struck across from

one of its tributaries to reach the mouth of the Prias in Kelantan.

During his years in Upper Perak, Captain Berkeley, I.S.0., had

frequent occasion to visit the DIu Temengor and the Piah valleys.

Still earlier than this period, pioneers had penetrated up the rivers

of the western slopes, but it must be remembered that their "ulu"

would now be regarded as our "kuala" and the real sources of the

rivers were correspondingly remote. Perhaps the best indication of

Journ. F. M. S. Mus. - Vol. XIX.

The Ulu Jindera. Kelantan.

from the Perak watershed.

A highland stream on the

PerakKelantan watershed.

Cliffs beside the Lower

Nenggiri. Kelantan.

A calm stretch of the

Beti s, Kelantan.

Plate I.

1936j An Outltne 0/ the ?erak-Kelantan watershed 11

this fact is that on the map published by St. Pol Lias in his amusing

book U Perak et les Orang Sakey," Ipoh (in very small letters) is

described as "village, Sakey ou Malaise." To-day of course, it is in the

Kinta region that development.reaches nearest to the Kelantan divide,

a:1d the lofty peak of Gunong Riam (Korbu) dominates the main

street of the town.

The French ethnologist de Morgan and Dr. Rudolf Martin;

Mr. F. W. Knocker, formerly of the Perak Museum, and of course

Sir Hugh Clifford, Sir W. E. Maxwell, Mr. Deane and Mr. H. W. C.

Leech also penetrated some way up the Plus and other tributaries 011

the western side.

In the last few years prospectors and others must also have

tracke_d up several rivers of the divide for some part of their length

especially on the western side. In such cases the Temiar have always

remembered to what point those travellers penetrated, and in other

quarters they said I was the first white man they had seen.

Circumstances have enabled the present writer to follow up most

of the rivers to their sources and to cross the main range five times

from West to East Coast Railway, thereby disclosing the Perak

Kelantan divide in a perspective which was not possible before. And

it was necessary to view the region as a whole in order to obtain a

just appreciation of the relativity of man and his environment.

The Main Features of the Territory and the Routes of the

Expeditions.

The observations of the surveyor!' who reached Noring and Grah,

and of course Riam, with readings taken from outlying ranges such

as Ijau, Bubu, Kledang and Tahan, give us some idea of the direction

of the main range, and reveal, though without popular recognition,

a series of sustained heights which are remarkable for Malaya. It

is almost certain now that no peak tops Gunong Tahan, yet Riam and

three other peaks come within a hundred feet of it, and there are at

least sixteen peaks of over 6,000 feeL

Although it is unlikely that undulating land of such continuous

extent as we have in the Ulu Telom will be discovered on the Perak

Kelantan divide, yet I have, in the course of my expeditions, come

across many smaller areas some of which might prove sufficiently

adjacent to one another to form other highland areas; and certainly

Cameron Highlands form only the southern end of these sustained

heights, separated from the northern ones by the knife-edge of Yong

Blar.

The higher peaks are almost dways shrouded in mist. The

heights around Gunong Grah, although lower than the more isolated

Gunong Korbu, being so close that the mist practically never lifts from

all parts of this mass simultaneously; it lies, moreover, not only

around the summits but extends to lower altitudes than is the case in

the other mountain groups.

12

Journal 0/ the F.M.S. Museums tVor.. XIX,

The sustained character of the heights along the divide give a

special character to the climate, and hence the flora. The stunted

trees weep with tangles of moss, which is a foot deep around their

base and hangs in decorative festoons from tree to tree. I was

reminded of the spectrous low trees on the higher slopes of Mount

Lompobatang, the extinct crater about 11,000 fe'8t high, which domi-

nates South Celebes. A continuous drizzle at these altitudes swells

the streams into mountain torrents and the high rainfall is responsible

for innumerable ravines and countle:'lS streams. The temperature can

be comparatively very low, and in the neighbourhood of Gunong Grah

during a halt on the Kelantan boundary at midday, fires were neces-

sary to promote suffic:ent warmth.

Five rivers drain the western slopes of the range, and run down

into the Perak river: the Sengoh, thE: Temengor, the Piah, the Plus

and the Kinta. Whilst on the east the Jindera, the Prias, the Betis

and the Brok join the Sungai Nenggiri, Kelantan.

The headwaters of all the riverfl drop over falls which are not

so much f.pmarkable for their height as for the long series of step,;

over which they cascade. The falls of. the Betis, called Lata Gajah,

are the most impressive that I found: though for sheer beauty

the falls of the Plus which thunder into a vast kind of "devil's

punchbowl" to join the Yum, almost surpass them.

When the streams descend to about four thousand feet they

generally How through a series of alluvial flats, separated at succeed-

ing le\'els by waterfalls. As one followed up a river, the steep and

arduous scramble up the side of falls was nearly always rewarded by

a pleasant walk through a flat valley. In some of these alluvial flats,

which will be described when the Various river valleys are treated

separately, river rejuvenation seems to have taken place, for now the

stream moves swiftly on a straight course, often cutting deeply into

the sandy soil deposited on an earlier meandering course, thus leaving

a flat shelf on either side. Some of these fiat valleys are of consider-

able extent, especially the Talong valley in DIu Sengoh just south of

Noring, and their significance for the population of these mountains

will emerge later.

When the rivers have descended to about two thousand feet

they become navigable by bamboo rafts, though formidable

rapids have to be negotiated at intervals, and also they are often

blocked at narrow stretches by tree logs washed down when the river

was in spate. Just below thousand foot level-sometimes as on

the Brok and the Sengoh, a considerable distance above the far Malay

kampongs-the furthest point upstream reachable by dugout boats is

usually situated. But often the most formidable rapids are found

less than a mile from these peaceful stretches of the river. as for

instance on the Brok, (Jeram Gaiah), the Piah, (Jeram Berhala), and

the Temengor, (Jeram Belanga).

1936] An Outline of the Perak-Kelantan 'Watershed

13

rrom the raftable limit downwards the bigger jungle begins and

fine trunks of merbau, meranti and tualang may be seen the

river. Above this point t.he timber is smaller and very inaccessible

from a commercial point of view. Having looked across the jungle

from summits at numerous pOints along the Perak-Kelantan boundary,

I was struck by the extenSIve areas of undisturbed virgin jungle.

Chronicle of Expeditions.

For the of the demographic survey, I crossed the

watershed on five main expeditions. The first two started from

Lasah, at the end of the Plus road from Sungai Siput. I marched up

the P.lus as far as Kuala Yum, followed one of its small tributaries

near Its source to int? the Ulu Ber which led me to the Sungai

I had during my first of intensive study of

Temiar culture III the Ulu Telom and Ulu Brok reached Kuala Ber

from the Ulu Mering, and indeed ha(l traced Brok as far up as

Kuala Blatop climbing back into the Ulu Telom near Blue Valley

(Ulu Ledlad) by a new pass not formerly used by the Temiar

owmg to the graves of several chiefs in the Ledlad. Coming from

the Plus on this occasion I rafted down the Brok as far as Kuala Betis

and :eached Gua Musang on the East Coast Railway six weeks after

Sungai Siput. Of this time, twelve days were spent in

marchmg and three days in rafting.

Then came three expeditions covering the Perak side of the

watershed, one from Ulu Korbu into the Ulu Plus at Kuala Mu and

then across Gunong Lalang into Ulu Yum again, and so down the

Plus to Lasah; a second from Kuala Temor on the Plus across into

the Piah valley and up into the Vlu Jemheng and down the

Temengor and the Perak River to Grik; and a third from Grik into

the Ulu Ringat and up the Temengor into the Piah val!'2Y, and so

down to the Perak River to Kenering.

In 1934 wei started from Lasah on my second expedition across

into Kelantan, this time taking a line further north by foIlowinO' the

Temor its source and so into Ulu Piah, finding the

of the Betts .lust by Gunong Grah. On this occasion when I arrived

after twelve marching dayg and tWG raftillg days at Kuala Betis I

rafted on down th8 Nenggiri, stopping at Kuala Jindera, and so reached

Bert.am, a station on the East Coast Railway-after two days of

rafting. One short expedition from Jalong on the Korbu into th'e DIu

Plus at Kuala Mu, lead me up the Mu to find the sources of the Brok

just below Yong Blar and so on up the Blatop to Cameron Highlands.

In April 1935, on my return from home heave, I followed the Kinta

up to Kuala Penoh and so reached the Telom by the DIu Penoh and

the DIu Terla. Another short journey from Grik to Kenering down

the Perak River enabled me to meet some PIe groups and neighbouring

Lanoh Negritos on the Lower Dalli.

On August 8th, 1935, I reached Kampong Temengor once again

from Grik, intending to get into touch with the most northerly hybrid

1 Mr. K. R. Stewart accompanied me on this expedition.

14 Journal of the F.M.S. Museums [VOl . XIX,

groups of Ple-Temiar, and so find the boundary between this hill tribe

and the Jahai Negritos. Striking the Sara, a tributary of the Sengoh,

wei turned north up thE:: Cherendong and so over a pass at 4,700 feet

from which we descended into a tributary of the Sengoh. We dropped

down into Kelantan to find the sourc:a of the Mpian, a large tributary

of the Jindera, which we followed down to a point navigable for rafts

(Kuala Perlong) but had to strike east again over a range of mountains

into the Ulu Jindera which we reached at Kuala Re!eng. From this

point we rafted into the Nenggiri again and so came out once more at

Rertam, eighteen days after leaving Grik, ten of which were spent in

marching and three in rafting.

On September 19th, 1935 I left Gua Musang for Kuala Betis and

rafted down to Kuala Yai, and so went up the last big tributary of

the Nenggiri still remaining to be visited by me.

2

From Kuala Prias

I followed north up the Prias for a day and then back to the Yai,

which was traced to its source, past Kuala Panes, opposite the source

of the Temengor. The reconnaissance was thus linked up again at

Kuala Jemheng with former routes

a

.

The. River Valleys.

The Plus.

The Plus becomes a peaceful and oft-travelled waterway after its

meeting with the Korbu, and soon wends its way between Malay

kampongs to meet the Perak River a few miles north of Kuala

Kangsar. It is from Kuala Korbu uluwards that the aboriginal

territory proper begins, though streams rising to the north-west of

Lasah must also be included. This area is defined clearly on the

accompanying map, upon which all the aboriginal settlements have

been plotted. There are two important strategic points above Kuala

Korbu, from the point of view of topography and hence distribution.

Kua.la Temor is the limit of perahu or sampan navigation and the

Temor itself is one of the larger tributaries of the Plus with several

hill groups living in its valleys. It also provides with its northern

streams the most accessible p a s s a g ~ into the Piah valley and thence

(via Sulieh and the Jemheng) to the valley of the Temengor.

A path was formerly made along this route joining Lasah and

Temengor, but I found in 1932 when I had sev'8ral occasions to u ~ e it,

that most sections of it had been overgrown. Another aboriginal

track follows up the Temor to reacn the delectable Ulu Piah, which

is isolated from the middle Piah,-served by the former route,-by

continuous waterfalls and precipitous ravines. The Ulu Temor

contains some very attractive J\at valleys one of which, though its

elevation was only about 2,500 we traversed for over a mile without

finding rising ground. Its extent is perhaps borne out by the fact

that though a long series of falls separate its peaceful reaches from

raft.able stretches of the lower river, yet bamboo rafts were seen

being punted along it.

I MI'. R. B. Black, M.e. s., accompanied me on this expedition.

2 Pater Schebesta had struck the Yai coming down the Panes from Ulu

Temengor.

3 Since this was \vritten a fifth expedition climbed back into Perak by the

Ulu Prias and 30 down the Kenyer into the Temengor.

journ. F. M. S. Mos. - Vol. XIX.

Camp at Kuafa Yai, Kef"nt .. n.

Shooting the rapids.

Plate II

Expedition on the march

up the Sara, Perak.

Railing on the Plus, Perak.

1936] An Outline of the Pera!c-Kelantan watershed 15

Kuala I.e.gap is the next strategic point upstream. This is the

limit above which rafting becomes impossible, though even between

it and Kuala Temor, the jerams Timah and Kerabut, prevent

undisturbed passage. Kuala Legap is therefure the capital, as it were,

of the upper pfus: the river here wends its way slowly between low

gradual slopes with many fiats on them, and on one of these a large

settlement comprising twenty families have their long house, and

a large plantation. In Legap. the Temiar from the furthest sources of

the Plus, are continually gathering: it is a recognised rendez-vous and

of great importance therefore to the administration of the area, since

one night on the way, at Kuala Temor, will bring any officer who

forewarns into touch with all the headmen of the Plus valley, for the

headwaters of the Plus open up like the fingers of an outstretched

hand with the tips pressed against the Kelantan divide.

The Legap, which rises on the slopes of Gunong Chingkeh is the

junction of two routes; one down into the PerIop, thence to the Korbu

and Jalong, and another up and across a large ridge to Kuala MH.

The Temiar wash tin just above Legap at Rengka. A few miles

upstream from Legap the Plus divides off from the Yum, a stream

from the north which actually rivals the Plus in size. Kuala Yum is

very beautiful; from just below it the Plus may be seen falling in

almost vertical steps in numerous cascades which just fail to be one

mighty fall of water well over a hundred feet in heig-ht. The

Yum also runs down precipitously, but upstream a few miles

at Kuala Pend uk, it is found to glide slowly over a series of alluvial

fiats, divided by precipitous stretches, and in these flats, and up the

Menlik which leads into the Ulu Piah and has its source opposite the

Jumpes and the Chular tributaries of the Betis, Kelantan, there are

a number of flourishing settlements: also one high on the slopes of

Gunong Lalang. The Yum valley runs like an index finger into

Kelantan, and its UPPH reaches flow through flat hig-hland areas

(as seen from Gunong- Lalang and the Ulu Panas, during the first

passage into Kelantan).

The next centre up the Plus proper ':which, after Kuala Yum

turns almost a hairpin bend until it is running from south to north)

is Kuala Mu. The junction of the Mu with the Plus takes place on

another fine area of gradual slopes. and is the site of a flourishing

settlement. So far to the sl)!.!th is Kuala Mu, that only a night on the

way, will bring one over the steep slopes of Gunong Chingkeh into

Jalong on the Korhu. Just below Kuala Mil, at Bakau on the Teras,

washing for tin is carried on.

There is no doubt that the Mu i ~ much bigger than the parent

stream when they meet. It follows a long and tortuous course from

the Kelalltan boundary, and there is an aboriginal track which will

take you into the Ulu Brok, the Sungei Nenggiri. Kelantan within

,,"each of lofty Yang Blar and lJlu Kinta. There are several

large areas in the Vlu Mu; including one (called for mythical reasons

"ben dang raja") which contains a thriving settlement. It is so flat

as to be boggy in some places.

16 JouriuLl of the F .M.s. Museums [VOL. XIX.

From Kuala Mu, the Plus, by now a small stream can be followed

up to (he Kelantan boundary in a .few hours. It runs .through

undulating hills, and at its source IS the only gap In the mal!1 range

of Noring, which provides a "pass" of great .value

when communications between Kelantan and Perak are m questIOn.

We now return to follow the Plus' largest tributary, the Korbu,

whose drainage area may be likened to an elongated trough. The

Korbu upstream to Jalong is a beaten and the scene of

elephant patrol but in the large valley Just upstream (Chabang) IS

situated one of the largest and most sophisticated Temiar groups,

from which the successful elephant patrol is recruited. These men

are adept "gembalas,"or elephant drivers, and have a.

plantation of most foodstuffs suitable for dry ThIS lme

of border forms a kind of aboriginal At

road-head is met again and there is a Chinese commumty of timber

cutters. Not far from Kuala Korbu is the flat valley of the Perlop.

Above Jalong, the Korbu is already a swift mountain

from Kuala Larek upst.ream it runs through narrow preCIpItous

ravin-es, and it is only when we climb above Kuala Kuah. that

meet peaceful slow moving waters. The Korbu curves and .ItS

source is close to the Ulu Mu and the headwaters of the Kinta, whIch

streams cut it off from the Kelantan boundary.

The Kuah curves round the south of Gunong Chingkeh, from

whose slopes, and from the lofty heights near Gunong R.iam on. its

other flank, it receives a number of swift streams. There IS a

hill 'long house' perched on a narrow ridge in from which

high peaks with sharpened summits may be seen rIsmg to south,

though the Korbu main peak is screened by closer mountams aln:ost

as high as itself. There is howeVer a tolerably easy. route over mto

the Ulu Mu which thus connects with the Ulu Nenggm, Kelantan, and,

further the DIu Telom. And there is actually much intercourse

between that' part of Temiar Pahang and Jalong, which sets the seal

on Jalong's significance as the test centre from which propaganda

may reach the furthest fields and serve a sphere which transcends

even the Ulu Plus; for we have alre&dy noted. that the sourC2 of the

Plus itself and the Mu are most rapidly reached from Jalong over the

Chingkeh !Jloc.

The Piah.

The Pia h rises under Gunong Grah in a series of headwaters

which contain several open valleys with gradual slopes, formed by

the accumulation of aU uvial flats. Just below Kuala Pi-es, I found

some pleasant smooth-featured country at about thr.ee five

hundred feet altitude (Kalong). Eut between thIS saucer and

Kuala Sulieh which I reached twice on my way to and from the

Temengor the Piah rushes headlong down impassable ravines. A

long day'S' march downstream from Kuala Sulieh .takes one Kuala

Puoi from which stream the Piah is raftable, but Just before It wends

peacefully into the Perak River. it goes through a long gorge aptly

named the "Jeram 13erhala," below which rafts may have to be

1936]

An Outline of the Perak-Kelantan watershed

17

constructed anew. The Piah valley is never wide, and the Puoi is the

only tributary of any size below Kuala Sulieh.

The Temen[lor.

The like the Jind.era, flows north and south, more 01'

less pa:allel WIth the general lme of the main range, unlike the

other rIvers of the watershed. It first becomes a considerable and

raftable river at Kuala Jemheg'N; the Jemheg'N, being almost as

large as the Temengor when they meet. The Temengor itself rises

on the slopes of Gunang .Grah beside the source of the Yai, for it

cur.ves round east of the hIgher mountains (Bieh and Sepat) formerly

belIeved to be the watershed. I have been both up and down the

Jemheg'N which Jehds into the habitable middle Piah valley, and we

traced the source of the Temengor itself climbing back from Kelantan

up the DIu Yai. After Kuala Jemheg'N there is one bad rapid the

" Jeram. Belanga,"' and the further north the Temengor flow; the

fu!ther moves from the watershed so that it receives two largish

trIbutanes, the Kenyer and the Kertei before it reaches the isolated

Patani settlement of Kampong Temengor. .

The Sara and Ulu Sengoh.

We struck down into the Sara after two days march from

Kampong Temengor i!1 a direction roughly north-east first following

the and Re.ndah and camped at Kuala Heng.' At this point

the Sara IS not naVigable for rafts, but it is particularly full of fish.

A: half day's march up the Sara, which revealed fine flat land on either

SIde, took us to Kuala Cherendong. Here we left the Sara itself

which rises, so we were told, south below Gunong Karang (7 120 feet

and hitherto unnamed on the map of Malaya, thouO'h it is the fifth

higbest peak in the peninsula), and followed up the Cherendong in an

east-north-easterly direction camping- at the foot of a range which

took us a long day's strenuous climbing before we reached the pass

at 4,700 feet. We descended towardfl nightfall, stumbling across the'

tracks of elephant (which the PIe said were very numerous in the

DIu Sengoh, as also tiger and other game further downstream) to

find ourselves in a long flat valley vI about 4,000 feet altitude which

we were astonished to find was the Talong, another tributary of the

Sengoh, wruch apparently rises far south and flows parallel with the

edge of the watershed for a number of miles. An hour's walk that

evening, and two hours of easy walking the next morning gave

us neither the downstream nor upstream limits of this fine land.

The stream and its tributaries glided along without a murmur over

sand, with patches of green water plants here and there, its windings

suggesting some breadth to the valley as well as length. Regretfully

we left the Talong and only a five minutes scramble UP a low slope

gave way to a descent on the other side. Only when I saw a little

brook running- swiftly did I realise, and receive confirmation. that we

had struck the source of the Mpian, a tributary of the Jindera, and

were in Kelantan. S(luth of NOlin:!. it appears, there is a kind of

elevated elongated "saucer" of land with the barest rim, on the east

side of which the land falls steeply away to the ra-vinei! and torrents

Of mu Mpian,

18

Journal of the F.M.S. Museums

[VOL. XIX,

The Ulu Nenggiri, Kelantan.

There is little doubt in my mind that' Nenggiri' it5 wor?

negeri' nasalised in the manner so habitual with the Se.no!.

Above Kuala Betis it is called by them the Brok' (MalaYlsed

Berong) and they assured me that it was the .. ibu Nengen

Kelantan, itu-Iah." The Nenggiri is a far larger river the. Galas

at their junction and Malays about there refer .to their meetmg

.. Kuala Sungei." The naming of the Kelantan rivers as elsewhere m

this country, is just what would fcllow from a people who spread

inland from the sea. It seems as if the Malays of Ulu Kelantan have

an origin different from those on the alluvial plain near the. sea.

They are the descendants of Moslemised Temiar, artd Malay

from the Jelai district in Pahang. The descendants of Chfford s

To'Gajah, one of the PHhang rebels, are living the ,ab?ve

Kuala Betis. It is still possible to exemplify habit, of mtI ud:n

g

Malay of misnaming rivers: one of the bigger o.f

Nenggiri is called by the local Malays" the Prias" and Its biggest

tributary the Yai. But the TemiaI" inhabitants of these

regard the Yai as the parent stream; and indeed it is the bigger at

their junction. ,

The Nenggiri is still from its source to its mouth a predommantly

aboriginal river. The "orang MiHayu" along its total Iength do !lot

reach a thousand souls, and most of these are kin of the Temlar,

who reach anything from four to five thousand m number.

The Brok.

The parent stream. called the Brok by the even as far

down as Kuala Jindera, rises just opposite the Ulu .K

mta

from the

eastern slopes of Yong Blar, not morc than twelve. miles as the crow

flies from Ipoh. Just before it meets the Galas It flows the

railway bridge near Bertam station. Like the parent Its

main tributaries all flow down eastwards from mam and

downstream from Kuala Betis, it does not dram an,Y consl.derable

t 'butarv from its right bank. It is the Brok which drams the

shield-like' enclave' between Perak and Pahang just from

Cameron Highlands. It receives the Terisuk and the Rengll. from

the north just under the southern headwaters of the (Sungel Mu).

and the Plaur, the Tauu and the Blatop from the rIm of

Highlands. All theSle rivers are like mountain torrents, rushmg down

steep ravines except at one or two points such as below Kuala Ledlad

on the Blatop, and the Brok itself above Kuala Blatop. But frO!Il

Kuala Blatop down to abouf three miles above Ber. Brok

sweeps down between steep- and rocky hill sides Which admit of no

track at all.

The Ber is the Brok's biggest , trihl!-tary. Its source lies

opposite the central headwaters of _ Plus, and after

swiftly down the steep eastern slopeS.' _ot Yong Yap. on which vast

landslides are visible from the north, it glides leisurely

down through fine wooded country to join the Brok which I? also

begiiming to repent of its rapid course and now has become naVigable

fQr raftg, -

1936] An Outline 0/ the Perak-Ketantan watershed 19

Kuala Ber lies in a region of numerous hot springs, great scars

of rock open to the sun, The hot springs begin two miles up the Ber

and persist for about a mile and a half up the Brok. Either bank is

dotted with them until well below Kuala Mering. The Mering itself

which rises opposite the Rening and the Misong in Ulu Telom is a

lovely river which shortly after leaving the low watershed glides

crystal-clear over golden sand set with rocks, from under which the

traveller sets shoals of fish darting to find new cover. The hot springs

begin about five miles up the Mering, and there must be a fault

running right by the Misong and so to the constellation of them

around the Ulu Tekal and Ulu Jelai Kechil in Pahang.

These hotsprings are the focus of game of all kinds, and I have

found deer, kijang, elephant, seladang and wild pig more plentiful

here than anywhere else on both slopes of the main range north-

wards, in spite of the proximity of the Temiar.

A day's rafting from Kuala Ber brings one to a great black gorge

called Jeram Gajah which is about a quarter of a mile in length.

After the torment of these rapids the Brok meanders peacefully

between low hills and the first Malay settlements are passed side by

side with the Temiar.

The Betis.

The Betis rises just under the peak of Gunong Grah opposite the

Ulu Piah from which river I climbed into its source. Just above Kuala

Jumpes, the Betis .flows for miles through undulating land below

four thousand feet altitude. About two miles above Kuala Telour,

it descends swiftly between steep hill sides and its precipitous course

ends about a mile below, with a beautiful fall, called Lata Gajah,

where the Betis, by now a considerable volume of water, drops over a

shelf for about eighty feet and then drops again in a series of smaller

falls. There are several hotsprings at the very head of these falls,

and evidence of plenty of game.

Below Lata Gajah, the Betis takes a slower and more circuitous

course all the while receiving few streams of note on its north bank

nor on its south, until the Enchin which has barely finished its abrupt

descent from the hills when its waters pour into the Betis. A long

bend on the river brings one to the mouth of the largest tributary,

the Perlob, on which most of the Temiar population is settled. The

Perlob has its source just opposite the Yum (Ulu Plus). Large herds

of elephant3 seem quite recently to have invaded the Perlob valley

and are devastating the crops of the Temiar.l

Below Kuala Perlob

2

, the Betis runs by the side of abrupt walls

of dolomitic formation, which stand out of the jungle like massive

fortresses.

From Kuala Betis, the Nenggiri flows northwards as far as Kuala

Jindera, dropping barely ten feet on the way and few rapids break

its even course. Near Kuala Peralong, a stream of no great size, there

are several hotsprings near its banks and game tracks become

plentiful again.

-------_._-

1 There is reason to believe that these new herds, which since this was

written have invaded the Prias, are part of the herds which, until the Elephant

Patrol disturbed them, used to do much damage on the Lower Plus.

2 or Perolah.

iou?'nai of the F.M.S. Mus eums ['VOL. XIX,

The PriM. .

About :.: ight miles aLove Kuala Jindera, the Prias joins the Betis.

This river is unlike the other big trilutaries of the Nenggiri, in that

the hills do not stand back from its hanks for the last. stretch above

its mouth.

From Kuala Yai to the mouth, it flows at great pace on a steady

descent. It risEs just south of Gunong Karang. It is a beautiful

rivEt', its course being marked by a series of rocky pools which arc

full of fish , klah and seberau being especially plentiful. The Yai and

its tributary, the rise near Ulu Temengor. The Ulu Yai runs

through a large area of flattish land of about 4,000 f(let above

sea level.

The Jindera (Tem:a?' "JendTol") .

The Jindera is the last great tributary of the N enggiri. Its

source is on the southern slopes of Gunong Noring opposite the Ulu

Sengoh . . We climbed into the source of its largest tributary, the

Mpian, which rises under the rim of the high plateau of the Talong.

It rushes precipitously down in narrow ravines as does its other

headwater, the Bertak, which seen from the ridge between the two

appears to be one vast series of fall s from first to last; th:! power in

. those waters must be considerable. Below Kuala Bertak, the Mpian

slows' down in a more open and along these beautiful

stretches, it is possible to raft. At Kuala Perlong we had, however,

to turn aside and c1imh eastwards over a high ridge into the Jindera.

The Jindera, where we carne upon it at Kuala Releng, was already

a considerahle stream and, from a mile or two above, its waters were

navigable for rafb;. The Jindera soon passes into an open landscape

set with great dolomitic pinnacles, whose cliffs make the views along

this river very lovely. The scenery becomes very stern in the rocky

trough in' which the Mpian joins it, whose formerly peaceful waters

have gathel'ed speed in a final fling before pouring themselves into the

Jindera. From Kuala Mpian till its mouth, the Jindera flows through

low land, t hough in several places it carves its way under the

dolomitic cliffs.

From Kuala Jindera, the Nenggiri turns sharply eastwards.

After Kuala Uias, it turns south round the steeps of Gunong Berangkat

and just after this passes close to the great rock of Keldung, which

the Tem..iar recognise as the boundary stone of their country. From

Kuala Betis to below Gunong Berangkat there are no Malay settle.

ments, but now a few isolated houses are found again. The stretch of

the Nenggiri about Ku,la Lah is studded once again with the rugged

dolomiti c cliffs (loose\) termed "limestone") which break the even

tone of the greer. jung!e wall on either bank. One of these Batu

Bayan, on the right bank is very striking, a long cave being rent about

two hundred feet up in the cliff.

But if this is the country of the Malays, it is also, as on the

Perak side. the beginning of the beat of the Negrito nomads for

bands of the Menri tribe move around in the Ulu Lah and ' U!n

Bertam and also on the lower Galas, in which river, below the railway

at Bertam. the greater waters of the Nenggiri attain anonymity.

JOV( II . f . Jrrwt . S. M",,- - Vol . ll".

W I

t Alo-.,.

1 .

I 1 I 1

I

1

to &

,

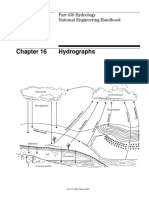

i t f

tlftVEAL!J6ICAL ANALYSIS <JF A (YflICAL TEMIAR UTfN(jE!J rAMILY

OCCI/PY/Nd II lONQ 1/(J(fiJf (IN mE .t.llfNIJ({i, II. TUOJ( PAItAN(i

dod ' ON es/oad (0 t he he;;7fn. Ii? t/u:> 1'Iv;r r/ tile Lq'!j"

/lowe beloW.

f t :: '

(tid) (di.J(It#MFri _dJ 1 l

=

l.:U

Ab6l'>?

t

I

f

l!J

"'i!JAcL

I

I I

l

,

(I(II a/cd ,y,tll'f ,""i/urI',?)

B

H f

t

J.

I WJ

.I

t f

!

A"!jd w,(,,, P.ltfJlv (o'd)

-'tQjt' #n

I

.2

f

I

f

Alli

J

"8

;;= AmiDt' :::;.. Aiv

dd l!J

1t.

I

t

/It."

w

V" 'Wrft#tl

li ... ... old

.. m

f f

t

A!

f

ifii t.d.> dd l1ar-si riJ

Alo dJ

6

A1o

og-

",., ,. ,..i<ltl

1 .L,.i. .L .l.,

r

____ ______ --,

I I I I I

I , I I I I

I I I I I I

___ :- - (0- - J - - -0 -- -(8 - - J L - - - ---_1 - - - - - -0 ---:- -. - -

I

!. 01

1

@ @ ri r"' Q) 0 C:

l

- - - - .. - - ___ - ..J ____ -l -: :-- - - - - - - - j" - - - - - -1- - - - - - -

, , I I I I

I

,

I I I

I " I:

Or NtJtnan f1"tJm (trrO/hfr group ,,110 = i =? 1T18n WI?II Two w"""s.

"HJ" (nla (n".; i-ily.

1936]

Breed and Culture

21

THE BREED AND TURE OF THE TEMIAR SENO!.

SOCIAL ORGANISATION.

. unit of Temiar Society is the .. extended family" which

inhabIts. a and works a ladangl. It is made up of

several mdividual famIlIes which are related to each in a

special way. The Temiar extended family is composed of a man and

some of hIS younger brothers and sist-ers, together with their mates

and families, in common occupation of a dwelling. It must be realised

t.hat in the process of descent several generations may

stIli be hvmg, and that uncles and aunts of these brethren will have

raised also. Family grouping is intermediate, neither patri-

local nor matnlocal residence being- binding on marriage: hence some

younger brothers may live with tht:irwife's group, whilst some of

the sisters may remain, their husbands joining them. Custom in

favour of the eldest son in each generation assuming leadership within

each household and there is increasing 'selection of the eldest f10n as

each generation succeeds. Continuity is thereby presened in the>

process of descent.

The institution of the human families comuosing- extended

households remains firm, and the ties which bind husband to wife

and children to parents are never oermanentlv weakened bv the

common factor in the extemled fl1milv. Each family consists of a

man and his wife or wives, with their unmarried children: the familiC:!s

occupy their own compartments and their own hearths around the

central floor. The extended household may indeed be regarded <lS a

small villag-e, the central floor being the street and the separate

compartrr:ents, the houses.

Society is a familv affair for the Temiar. Everybody is

addressed' or referred fo by his appropriate kinship term. The

system of relationshios being" classificatorv," terms such

as "father" and "sister" refer to groups of relatives. and those

too remote to be included in our European svstem are specified ami

classed with close blood-kin. Differential treatment ann. certain

reciprocal duties exist between kin applying the same relationshin

term to each other. These classed under the saIY'e term are "sodal

equivalents" as far as performance of custom and ritual surrounding-

the of birth, marriage and the like are concerned. Semantic

recognition of the real parents and blood-brethern is however always

present. .

As will be noted when marriage customs are it is not

binding on a young man. either to reside permanently with his own

people nor with his wife's: generally a young couple move from one

group to the other. Kinship organisation is not localised: it involves

grouns on the Neng-giri, the Telom. the Plus .. the Korbu and the Kinta:

a. Pahang Temiar finds dose relatives in the Korbu in Perak, and in

the Betis in Kelantan.

Everv extended household. on the other hand. a un;t in a stil!

wider grouping, which is ot several such households; this

wider grouping is called the and the part plaved bv the

kindred in law, and its identification from the economic point of view,

with a territory of land called the" saka" is deS1lt with I_ater. __ _

1 A Malay word meaning a jungle clearing for dry cultiyation.

22 Journal of the F.M.S. Museums [VOL. XIX,

The prohibited degrees of relationship within which mating may

not occur are defined by the ancestral law of Incest: "those who

have drunk the same milk may not sleep together." Even cousins

are debarred, and eligible mates are not found within the extended

household, except in certain cases his relatives may follow a

man who has married into another household and thus provide

mates for other members of tl:e hous-ehold.

Preliminary bargaining between the two groups represented by

the lovers may be complicated: yet there is no ceremony to initiate

matrimony. Courtship involves premarital intercourse, but contented .

co-habitation is the seal of marriage. Temiar are no less faithful

than most to the marriage pact: unions are contracted young and are

soon cemented by the breeding of several children who form a tie

that is rarely severed. Either husband or wife may find temporary

bed-mates, but these do not affect the union. A younger brother

will often sleep with his elder brother's wife in the latter's absence.

Whilst on a journey it. is permitted for a man to spend the night

with any female relative of hi"! wife. Such accommodations usually

become known to the real husband but it is bad form to show jealousy.

Custom allows two wives, although one is the more general:

in some areas polyandry occurs. A man must be diligent enough to

satisfy the parents of a girl whom he wishes to make his second

wife. Attempts to marry more than two wives are very rare and

are regarded with the utmost disfavour. During the period of his

courtship the bridegroom begins to pay visits to the household of