Professional Documents

Culture Documents

European Shale Gas and Russia

Uploaded by

whjoceCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

European Shale Gas and Russia

Uploaded by

whjoceCopyright:

Available Formats

Shale Gas Exploitation in Europe and the Effects on Russia

The renewable energy revolution remains elusive and fossil fuels will continue to power much of the worlds economy for some time to come. Yet technological advances in recent years mean that shale gas promises change almost as significant as renewables in breaking up the fragile yet vital supply chains of energy that snake across the globe. In enabling countries to meet more of their own energy needs and so import less, the exploitation of shale gas reserves will have acute geopolitical consequences across the world. This is particularly the case in Europe where the monopolistic relationship between Russia and its various gas-client states is longstanding and dates from the days of the Cold War. The primary supplier of the European gas market is Gazprom, a joint stock company 50.1% owned by the Russian Federal Government. With a market capitalisation as of May 2013 of $111.37 billion it was once expected to become the worlds largest company but consistently depressed growth in its primary market since 2008 has more recently limited its ambition. Russias economic and political institutions are fragile structures with great reliance on the income from exported natural resources. This means that the country could face profoundly negative consequences domestically and for its foreign policy due to the use of shale gas in European energy markets. The Status Quo Approximately 25% of Europes current demand for natural gas is supplied by Russia, primarily through pipelines stretching eastward across the steppe to gas fields in the remote arctic north and Siberia. However Russias percentage of the market is significantly higher for countries in Eastern Europe, particularly those still reliant on Eastern Bloc energy infrastructure or geographically isolated. Russias share of these markets is between 75 100%. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is the current main competitor to Russian pipelines in bringing gas to the European market. The liquefaction process vastly reduces the capacity of the gas, making it possible to import the amounts needed on shipping tankers from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Yet the infrastructure required to handle and process LNG is expensive and shipping lanes passing through distant trouble spots such as the Straits of Hormuz make the supply lines vulnerable. Perhaps the most notable factor of the European relationship with Russia in the gas market during recent years has been the willingness of Russia to engage in so called pipeline diplomacy. This is in keeping with Vladimir Putins doctoral thesis that proposes Russias natural resources should be used as a means of gathering political as well as economic power. In practice, pipeline diplomacy has been used in three ways. Neighbouring countries have been threatened by Russia in having their gas supplies cut off unless they agreed to new prices or pay off debts. As gas for EU markets must still transit these countries there is no practical way of separating the two supplies. When Ukraines gas was shut off in disputes between 2005 and 2009, distant Italy was unable to meet its gas needs and images of shivering pensioners filled news bulletins across Europe.

Conversely, the construction of the Nordstream pipeline under the Baltic from Russia to Germany was aimed at reassuring Western Europe about the security of their gas supply by avoiding any transit countries. The different treatment meted out to different consumer countries is as stark as it is deliberate with no guarantee that the prevailing mood will not change at short notice. Lastly, Russia has used pipelines as a way of attempting to maintain their dominance of the European gas market by actively targeting potential alternative supplies. For example the proposed Nabucco pipeline would have brought gas from Central Asia to Europe without crossing Russian territory. Gazprom countered by swiftly constructing pipes its own, the South and Blue Stream projects that have rendered the Nabucco pipeline obsolete before it has even been constructed. The western section of Nabucco will now link to the Russian network with gas from Turkmenistan making an enormous detour northwards through Russia before reaching the markets of the West. Expected Changes New technology has made it possible and economically viable to retrieve natural gas trapped in shale rock formations. This is in contrast to traditional reserves of gas such as those in Russia that are stored in looser geological formations and so are easier and cheaper to extract. Reserves of shale gas have been found in countries that have conventionally been large importers of energy and it therefore has the potential to bring significant changes to the global energy market. This is often referred to in more excitable headlines as a forthcoming shale gas revolution. Key known basins of shale gas have been found in the Baltic States, across Poland and Northern Germany and in the UK in addition to other locations in Europe. It is unclear how long it will take for regulatory hurdles to be overcome, infrastructure constructed and these reserves come online, but they have the potential to significantly reduce the need for European countries to import gas, either from Russia through pipelines or as LNG from MENA. The emergence of shale is expected to be a final catalyst for the creation of a common EU energy policy. This would end the ability of Russia to play divide and rule with EU countries in regards to its pricing structure, which is currently so erratic as to verge on the bizarre. Common negotiation across all EU member states would increase the bargaining power of the entire block, protect smaller countries from exploitation and increase the stability of the European energy market. A united front in bargaining with Russia for gas will be a good way of getting a better price in general terms. However, it would also specifically be the best chance in a generation to break the fixed price link between oil and gas. Economists and politicians in energy importing countries have been urging this for decades but collusion between producing countries, which benefit greatly from the status quo, has until now kept the link firmly in place.

Economic effects in Russia

In the years since the global financial crisis began in 2008 the revenue from sales of oil and gas has made up approximately half of the revenue for the Russian Federal Budget. The remainder is made up of VAT, tariffs on imports, income tax and smaller revenues from other taxes. Therefore any significant fall in oil and gas revenue will have a knock-on effect for the budget as a whole. However while the problem will be considerable that does not mean it will necessarily be immediately catastrophic, as has been suggested by some commentators. Just within the economic sphere of gas and Gazprom the Russian government will have several options to pursue. For example selling more gas to countries outside the EU, raising prices for countries currently enjoying subsidies and striving further to reduce operating costs to maintain profit levels from reduced sales. This last choice could be highly successful as ever increasing revenues from European gas sales have reduced the incentive for Gazprom to increase its productivity. With Russian industry generally remaining horrendously inefficient, reducing costs and waste would be an effective response to the challenge of shale. Meanwhile a range of developing markets have the potential for sales growth. China has discovered its own large reserves of shale gas but to maintain an adequate energy mix for its growing economy it will still import more Russian gas than is currently the case. Additionally, the development of more LNG terminals on Russian coastlines will enable tankers to deliver Russian gas to new markets all over the world. The full economic effect on Russia of shale gas in Europe will depend on one hand on the speed with which the reserves are tapped and, on the other, the speed with which Russia reacts. From what has happened so far it would appear that the bureaucratic inertia of the European courts, goaded by environmentalist campaigners, is still moving faster than the bureaucratic inertia of the Gazprom management, who are complacently happy to assume that their dominance will remain undisputed. While President Putin has challenged Gazprom to find a solution to the riddle of shale, few practical steps have been taken. In the short term, as European shale reserves come online in the next few years, Russian revenue will fall. Government spending may fall in parallel but the large reserves Putin has built up during his time in the Kremlin mean that the government can run a deficit for a sustained period if necessary. But both these options clearly demonstrate that the economic effects of falling revenue will be matched if not exceeded, by the political consequences. Political effects in Russia The most basic political effect the process of European shale gas exploitation will have in Russia is to expose the abject failure of the Putin project to modernise the economy. Throughout the last decade the Russian leadership has paid lip service to the idea that the country should diversify into innovative, profitable industries, support a new entrepreneurial class and develop a modern service sector. All this has failed and the country remains over reliant on its primary industries. Any reduction in spending by the government in Russia will sharpen public focus on another failure of the last ten years, the still rampant corruption endemic at every level of society. This has been masked by increases in government spending and rising living standards but the vast amounts of money that disappear into the black economy and offshore bank accounts

are a serious drag on the countrys efficiency and represent blatant theft from the majority of the population. If tougher spending decisions are needed, as seems likely when these effects take place, one option that will be pushed for by Gazprom managers will be the reduction or removal of gas subsidies for the Russian population. These currently see gas for domestic consumption sold at very cheap prices far below what is realistic to cover the cost of extracting it and transporting it to market. The domestic prices are set by the Federal Tariff Service and reflect the political need to control cost of living increases. It is likely that there will be tension within the government if these two forces come into conflict in the near future. The effect on foreign policy will be exactly what Gazprom has spent the last decade and millions of dollars trying to avoid, which is a reduction in Russias political leverage in Europe. On a range of issues including visa free travel, financial integration and security cooperation, Russia has relied on its position as an important energy source in pushing for favourable agreements with Europe, either bilaterally or through the EU. Dialogue will continue and agreements will still be forthcoming. However the Russian negotiating teams will have to work harder with less power than they have enjoyed before. Conclusion There is currently no credible replacement for the revenue the Russian Federal Government receives from selling natural resources abroad. Trade, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), innovation and entrepreneurs are all throttled by the gross levels of corruption in the economy and the inefficiencies brought with it. The ability of Mr Putins regime to maintain control without the money to guarantee rising incomes for all must be brought into question. Therefore as part of wider changes in the global energy markets, falling gas revenues from Europe will play a role in destabilising Russia in the coming years. The leadership can take steps to mitigate these effects but each option to do so will have further costs of its own to be borne by the country as a whole, the Federal Government or the Russian people. Social commentators in Moscow and foreign observers agree that to predict the future likelihood of civil unrest and political tension in Russia you only have to watch the energy prices. Shale gas will put long term downward pressure on those prices. The dual proposition of more unrest with a greater tendency for the regime to crack-down violently against dissent suggests that greater volatility must be seen as a likely prospect for Russias mid-term future as a result of the exploitation of shale gas in Europe.

You might also like

- Can Europe Survive Without Russia's Natural Gas? Part I: Maybe, But It Should Not Have ToDocument5 pagesCan Europe Survive Without Russia's Natural Gas? Part I: Maybe, But It Should Not Have ToGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Russia and The Geopolitics of Natural Gas Leveraging or Succumbing To Revolution?Document6 pagesRussia and The Geopolitics of Natural Gas Leveraging or Succumbing To Revolution?Adriana RuedaNo ratings yet

- Biden's gas air lift to help Europe abandon Russian gasDocument3 pagesBiden's gas air lift to help Europe abandon Russian gasFaith Van WartNo ratings yet

- Russian Energy Markets 2Document19 pagesRussian Energy Markets 2SobiChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Can Russia Really Solve Europe's Gas Woes On Its OwnDocument4 pagesCan Russia Really Solve Europe's Gas Woes On Its OwnGiorgi SoseliaNo ratings yet

- Insight NB 14.7.22Document4 pagesInsight NB 14.7.22asifraNo ratings yet

- The Shale Revolution's Global FootprintDocument4 pagesThe Shale Revolution's Global FootprintEquipo CuatroNo ratings yet

- South Stream Pan European ProjeDocument3 pagesSouth Stream Pan European Projechristiana_mNo ratings yet

- Russian Exports DADocument23 pagesRussian Exports DACarolineNo ratings yet

- Shale Gas Drilling in Easter Europe: A New Energy Frontier or Another Reckless Operation?Document8 pagesShale Gas Drilling in Easter Europe: A New Energy Frontier or Another Reckless Operation?VilladelapazNo ratings yet

- Cato Policy-Analysis-957Document36 pagesCato Policy-Analysis-957Alpha TraderNo ratings yet

- LNG Demand Outlook in Atlantic Basin After Two Winters of Price VolatilityDocument18 pagesLNG Demand Outlook in Atlantic Basin After Two Winters of Price VolatilitythawdarNo ratings yet

- Emmanuel Olayinka Adeboye R2205D14535270: Governing International Oil and Gas (UEL-SG-7301-33314)Document14 pagesEmmanuel Olayinka Adeboye R2205D14535270: Governing International Oil and Gas (UEL-SG-7301-33314)Emmanuel Adeboye100% (1)

- SECURING EUROPE'S ENERGYDocument0 pagesSECURING EUROPE'S ENERGYioannisgrigoriadisNo ratings yet

- ShaleGas JaffeRice WSJ050510Document11 pagesShaleGas JaffeRice WSJ050510Matthew PhillipsNo ratings yet

- EU and GCC Energy Partnership in CrisisDocument3 pagesEU and GCC Energy Partnership in CrisisBilal MalikNo ratings yet

- European Gas Policy in TroubleDocument4 pagesEuropean Gas Policy in TroubleGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Seminar Presentation: Security of Supply Diversification of SuppliersDocument14 pagesSeminar Presentation: Security of Supply Diversification of SuppliersVasco LaranjoNo ratings yet

- Atradius Economic Research European Gas July 2018 Ern180710Document3 pagesAtradius Economic Research European Gas July 2018 Ern180710aliNo ratings yet

- The Past, Present and Future of Russian Energy StrategyDocument8 pagesThe Past, Present and Future of Russian Energy StrategyVictor CiupNo ratings yet

- Book Review of The New Geopolitics of Natural Gas by Lee MorrisonDocument6 pagesBook Review of The New Geopolitics of Natural Gas by Lee MorrisonThe International Research Center for Energy and Economic Development (ICEED)No ratings yet

- Russian Energy Sector EvolvesDocument4 pagesRussian Energy Sector EvolvesDiana BărbuceanuNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas in The Russian FederationDocument11 pagesNatural Gas in The Russian FederationIke Ikechukwu MbachuNo ratings yet

- Surging Liquefied Natural Gas TradeDocument28 pagesSurging Liquefied Natural Gas TradeThe Atlantic CouncilNo ratings yet

- The Geopolitics of Oil and Gas: Energy PricesDocument3 pagesThe Geopolitics of Oil and Gas: Energy PriceserkushagraNo ratings yet

- Opportunities in The Development of The Oil & Gas Sector in South Asian RegionDocument20 pagesOpportunities in The Development of The Oil & Gas Sector in South Asian RegionMuhammad FurqanNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas in The Xxi CenturyDocument11 pagesNatural Gas in The Xxi CenturyMarcelo Varejão CasarinNo ratings yet

- Russian Gas NordstreamDocument7 pagesRussian Gas NordstreamarchaeopteryxgrNo ratings yet

- Potential Triggers for European Gas Supply DisruptionsDocument21 pagesPotential Triggers for European Gas Supply DisruptionsEffe BiNo ratings yet

- Gas Presentation14 TowardsGlobalGasMarket RSkinner 2004Document18 pagesGas Presentation14 TowardsGlobalGasMarket RSkinner 2004LTE002No ratings yet

- Capturing Value in Global Gas LNGDocument11 pagesCapturing Value in Global Gas LNGtinglesbyNo ratings yet

- Energy Demand Behaviour in Competitive Open MarketsDocument6 pagesEnergy Demand Behaviour in Competitive Open MarketsstoicadoruNo ratings yet

- CHP/DH Country Profile: RussiaDocument12 pagesCHP/DH Country Profile: Russiaera1ertNo ratings yet

- Energy Strategy Reviews: Anton OrlovDocument10 pagesEnergy Strategy Reviews: Anton OrlovMario DavilaNo ratings yet

- The Bridge: Natural Gas in a Redivided EuropeFrom EverandThe Bridge: Natural Gas in a Redivided EuropeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Russia-Ukraine War Its Impact To Global Oil Economy by Jamie AbadDocument8 pagesRussia-Ukraine War Its Impact To Global Oil Economy by Jamie AbadJamskiii asdjdgdfghjmklNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topic and OutlineDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Topic and OutlineAnna SHEVCHUKNo ratings yet

- China-Russia Gas DealDocument8 pagesChina-Russia Gas DealIlham Syakbanur Rahmat 1401112891No ratings yet

- 2018 - NATO and Gas From RussiaDocument22 pages2018 - NATO and Gas From RussiaAnonymous uLW3sszb100% (1)

- IEDocument44 pagesIEAndy DolmanNo ratings yet

- 01pa Aq 3 4 PDFDocument8 pages01pa Aq 3 4 PDFMarcelo Varejão CasarinNo ratings yet

- Eprs Bri (2021) 690705 enDocument12 pagesEprs Bri (2021) 690705 enZestyCableNo ratings yet

- Is LNG The New Oil?: Energy TransformationDocument7 pagesIs LNG The New Oil?: Energy Transformationsunil_nagarNo ratings yet

- Call Putin's BluffDocument2 pagesCall Putin's BluffPaco RamosNo ratings yet

- (12en) A Strategic Battle For EnergyDocument9 pages(12en) A Strategic Battle For EnergyforlandiNo ratings yet

- EU Shale Gas Myths and TruthDocument7 pagesEU Shale Gas Myths and TruthdownbuliaoNo ratings yet

- PC 2014 15 PDFDocument14 pagesPC 2014 15 PDFBruegelNo ratings yet

- The Energy Perspective Series: The Crowning in The Russian Cap, ET EnergyWorldDocument6 pagesThe Energy Perspective Series: The Crowning in The Russian Cap, ET EnergyWorldRamisha JainNo ratings yet

- Project Background: Nord Stream 2 AG - Feb-21Document7 pagesProject Background: Nord Stream 2 AG - Feb-21aqua2376No ratings yet

- The 15 Oil and Gas Pipelines That Are Changing The World's Strategic MapDocument16 pagesThe 15 Oil and Gas Pipelines That Are Changing The World's Strategic MapAkshat GuptaNo ratings yet

- The EU's Strategy Towards External Gas Suppliers and Their Responses: Norway, Russia, Algeria and LNGDocument24 pagesThe EU's Strategy Towards External Gas Suppliers and Their Responses: Norway, Russia, Algeria and LNGVisal SasidharanNo ratings yet

- 03po Ab 3 4 PDFDocument7 pages03po Ab 3 4 PDFMarcelo Varejão CasarinNo ratings yet

- General Background Paper On Nord Stream 10 20131128 1Document5 pagesGeneral Background Paper On Nord Stream 10 20131128 1Jerry KleinNo ratings yet

- Global Business Environment Individual Assignment: Submitted By: Jai Aggarwal 21Dm249Document16 pagesGlobal Business Environment Individual Assignment: Submitted By: Jai Aggarwal 21Dm249JAI AGGARWAL-DM 21DM249No ratings yet

- Trend in Europe Gas MarketDocument3 pagesTrend in Europe Gas MarketSuvam PatelNo ratings yet

- Eprs Bri (2021) 690705 enDocument20 pagesEprs Bri (2021) 690705 en20070304 Nguyễn Thị PhươngNo ratings yet

- Energi DuniaDocument7 pagesEnergi DuniaBerlianNo ratings yet

- Will Ukraine War Revitalise Coal - World's Dirtiest Fossil Fuel Climate Crisis News Al JazeeraDocument1 pageWill Ukraine War Revitalise Coal - World's Dirtiest Fossil Fuel Climate Crisis News Al JazeeraEdward MuolNo ratings yet

- Energy Security Gas OPECDocument3 pagesEnergy Security Gas OPECRenee WestraNo ratings yet

- Multi Modal Logistics HubDocument33 pagesMulti Modal Logistics HubsinghranjanNo ratings yet

- Review LeapFrogDocument2 pagesReview LeapFrogDhil HutomoNo ratings yet

- Group e - MetrobankDocument24 pagesGroup e - Metrobankhanna jeanNo ratings yet

- CSR Practices of Indian Public Sector BanksDocument6 pagesCSR Practices of Indian Public Sector BankssharadiitianNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial India: An Overview of Pre - Post Independence and Contemporary Small-Scale EnterprisesDocument8 pagesEntrepreneurial India: An Overview of Pre - Post Independence and Contemporary Small-Scale EnterprisesInternational Journal of Creative Mathematical Sciences and TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Relationship Marketing: Lesson 2.1Document66 pagesThe Concept of Relationship Marketing: Lesson 2.1Love the Vibe0% (1)

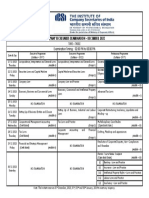

- Time Table CS Exams December 2023Document1 pageTime Table CS Exams December 2023Himanshu UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Worksheet - Rectification of ErrorsDocument3 pagesWorksheet - Rectification of ErrorsRajni Sinha VermaNo ratings yet

- India Strategy - Booster shots for key sectors in 2022Document210 pagesIndia Strategy - Booster shots for key sectors in 2022Madhuchanda DeyNo ratings yet

- Acounting For Business CombinationsDocument20 pagesAcounting For Business CombinationsMathew EstradaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document5 pagesChapter 4Syl AndreaNo ratings yet

- Trade Discount and Trade Discount Series.Document31 pagesTrade Discount and Trade Discount Series.Anne BlanquezaNo ratings yet

- Session 4 - Internal Control Procedures in AccountingDocument15 pagesSession 4 - Internal Control Procedures in AccountingRej PanganibanNo ratings yet

- FMCG Sales Territory ReportDocument21 pagesFMCG Sales Territory ReportSyed Rehan Ahmed100% (3)

- ALL IN MKT1480 Marketing Plan Worksheet 1 - Team ContractDocument29 pagesALL IN MKT1480 Marketing Plan Worksheet 1 - Team ContractBushra RahmaniNo ratings yet

- BCG Matrix ModelDocument10 pagesBCG Matrix ModelGiftNo ratings yet

- IAS 2 Inventories SummaryDocument16 pagesIAS 2 Inventories SummaryCorinne GohocNo ratings yet

- The Ultimate Guide To Profitable Option Selling - Predicting AlphaDocument4 pagesThe Ultimate Guide To Profitable Option Selling - Predicting AlphaCristian AdascalitaNo ratings yet

- LCG LCPharma EN 160421Document11 pagesLCG LCPharma EN 160421Patrick MontegrandiNo ratings yet

- 12BIỂU MẪU INVOICE-PACKING LIST- bookboomingDocument7 pages12BIỂU MẪU INVOICE-PACKING LIST- bookboomingNguyễn Thanh ThôiNo ratings yet

- Urban Liveability in The Context of Sustainable Development: A Perspective From Coastal Region of West BengalDocument15 pagesUrban Liveability in The Context of Sustainable Development: A Perspective From Coastal Region of West BengalPremier PublishersNo ratings yet

- NDC v. CIR, 151 SCRA 472 (1987)Document10 pagesNDC v. CIR, 151 SCRA 472 (1987)citizenNo ratings yet

- Ds 3 ZJG PFA8 VV 0 Uhb Itzm K2 ARl EGBc 82 SQB 9 ZHC 4 PDocument1 pageDs 3 ZJG PFA8 VV 0 Uhb Itzm K2 ARl EGBc 82 SQB 9 ZHC 4 PprabindraNo ratings yet

- Eighth Plan EngDocument419 pagesEighth Plan EngMurahari ParajuliNo ratings yet

- ROSHNI RAHIM - Project NEWDocument37 pagesROSHNI RAHIM - Project NEWAsif HashimNo ratings yet

- Kop Epc Poa Denny JunaediDocument1 pageKop Epc Poa Denny JunaediMarvelo Dimitri 4BNo ratings yet

- ENTR510 Final Assignment KeyDocument5 pagesENTR510 Final Assignment Keystar nightNo ratings yet

- Consumer Rights and ProtectionsDocument46 pagesConsumer Rights and ProtectionsSagar Kapoor100% (3)

- TDS On Real Estate IndustryDocument5 pagesTDS On Real Estate IndustryKirti SanghaviNo ratings yet

- CCM Chapter 1 SummaryDocument8 pagesCCM Chapter 1 SummarySalsabila N.ANo ratings yet