Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Priorities

Uploaded by

American Council on Science and HealthCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Priorities

Uploaded by

American Council on Science and HealthCopyright:

Available Formats

Priorities Volume 8, No.

2

Questioning the Vision of the Anointed by Dr. Philip Cole I commend Jacob Sullum for his thoughtful feature, What the doctor orders. I will try to expand on several issues that he raises. Mr. Sullums title is catchy but somewhat misdirected, as the article itself never mentions practicing physicians. This is appropriate, for physicians and other medical care providers are not responsible for the problems that Sullum addresses. He does point out the culprits, correctly indicting the overweening staffs of the health-oriented regulatory agencies that permeate our governments and also some members of the public health professions. Many of these groups have prominent directors whom Sullum gently chides as official nags. But it is the aspiring nags who create the problems. These zealous propagandists (educators, they say) and uncompromising advocates of regulation constantly try to regiment our lives in the name of health. The galling irony is that most of these busybodies are on public payrolls and use the authority of government to restrict that which government is supposed to enhance: freedom. What gives rise to this zeal and inflexibility? These characteristics are innate to the many members of public health groups and practice agencies who are possessed by what the noted social commentator Thomas Sowell terms the vision of the anointed. Their mission is divine, and so you will agree with them or be labeled a fool or knave. As a recent example, I drew fire when I supported a switch to smokeless tobacco for inveterate smokers. After misrepresenting this position, one of the anointedin this case one with the vision that tobacco in all forms must be eliminatedaccused me of unethical behavior and assured medical care providers that recommending smokeless tobacco would leave them legally liable for damages. Yet, this visionary is not known to have expertise in either ethics or law. Sullum generously looks beneath the sanctimony of the anointed for the basis of their presumed good intentions. He identifies this as the unqualified acceptance of the paramount importance of health. This is easy to understand, for the belief that good health is beyond price was drummed into all of us at our parents knees. But the belief requires questioning and examination. Such considerations suggest that good health is indeed priceless, but not paramount. This was put directly, in a New England Journal of Medicine letter, by a patient who was an incorrigible smoker. You know, doctor, he said, there is more to life than good health. Indeed, there is much more. A person who has self-respect and freedom values these above health; a person who has self-respect but not freedom values them higher yet. Sullum recognizes that the preservation of health is not, in itself, a sufficient justification for a public health intervention. How then, does one legitimize such interventions? Sullums implied response is that a combination of justifications is required: maintenance of health; protection from harm that may be done by others; and respect, to the extent possible, for the individuals sovereignty over himself. A compromise among these considerations usually can be met for interventions intended to control contagious diseases or environmental threats that are not perceived or readily avoided by the individual. More generally, Sullum is telling us that because the good health is all goal has competitors for supremacy, the justification of many public health interventions is complex. Recently, I attempted to explore the justifiable bases for public health interventions. Astonishing. The literature on this most fundamental, most important of issues is virtually nonexistent. I therefore prepared The moral bases for public health interventions to stimulate thought in this area. Virtually all public health interventions fall into one of four major categories: education, advocacy, legislation and research. More importantly, all interventions have one or more of but five

justifications: enhancement of individual will, paternalism, commonweal, common resources and good purpose. I contended that of these five, only the first three are usually moral, whereas the fourth and fifth virtually never are. Learned peopleincluding Mr. Sullum, his supporters and his detractorswill examine many issues in pursuit of the legitimate bases for public health interventions. But while this goes on, free people will continue to shun the supposed and even the genuine healthful behaviors that do not suit them. It must be so, for the simple reality is that all but the visionaries understand that . . . doctor, there is more to life than good health. Philip Cole, Ph.D., is Professor of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health, University of Alabama, Birmingham

Seeking Equilibrium in a Problem-Driven Field by Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg In his article, What the Doctor Orders, Jacob Sullum argues for a laissez-faire approach to public health threats arising from lifestyle choices. He complains that public health overreaches its legitimate bounds when it looks beyond traditional concerns with communicable disease. He especially objects when public health interventions intrude on individual freedom of choice. While public health professionals do often rely on the metaphor of epidemics, the field today embraces much more than communicable disease, and rightly so. Fundamentally, public health is a problem-driven field that emphasizes the burden of illness and disability at any point in time. Today, any honest assessment of the burden of premature morbidity and mortality points inexorably to problems like injury and violence that fall outside the traditional concept of epidemic disease. Individuals can discover for themselves, influenced by the powerful example of family and peers and the appealing images of advertising, the pleasures of smoking, drinking, eating fatty foods and any number of other behaviors that may eventually harm their health. Certainly, as Mr. Sullum says in his article, some people may opt for a brief, intense existence full of unhealthy practices. But are choices made, for example, on the basis of cigarette advertising truly informed? It would be irresponsible for those concerned about health not to make vigorous efforts to provide the information that gives individuals the opportunity to make reasoned choices about how they will live and to understand how they may die. The unconscious boundaries affecting choices in everyday life are powerful because they are often invisible. That these forces are invisible, however, does not mean that they are value-neutral. In fact, they include such elemental values as freedom and health. One consequence of public health efforts is to make these values more visible by attempting to shape policies that promote healthful incentives and boundaries, subject to law and respect for human rights. As a society, we agree to give up certain liberties for the common good, while defending the boundaries of individual rights. As Mr. Sullum correctly observes, A government empowered to maximize health is a totalitarian government. Over the years, policies on mandatory seat-belt use, speed limits, drinking ages and so forth tend to surge and recede as the body politic seeks an equilibrium between liberty and constraint that is acceptable at a particular point in time. When arguing in favor of social policies that constrain liberty, the case for protecting the common good must be persuasive. Perhaps even more insidious than the dangers perceived by Mr. Sullum are proposed restrictions on the rights of individuals (such as excluding from school those infected with HIV) where the facts of risk do not warrant the intrusion. The broad mission of public health has always been the promotion of health and the preven-

tion of disease and injury. The field naturally evolves as some health problems are solved and others gain prominence; today, heart disease, cancer, injuries, and new infectious diseases such as AIDS. Great gains have been made over the course of the century; further gains remain to be made. As society changes, as our physical environment evolves, as our definition of health shifts, public health must continue to recognize and to concern itself with the major contemporary threats to human well-being. Harvey V. Fineberg, M.D., Ph.D., is Dean of the Harvard School of Public Health.

Rx: A Strong Dose of Moderation by Dr. Lawrence W. Green Jacob Sullum takes issue with government initiatives to tilt the heath-behavior balance back in favor of moderation. He does so with a cynical eye on history and bureaucracy that characterizes American political commentary from the right. Ironically, his position brings him to the same criticism of government that has characterized the attack from the left: that government should not focus its public health efforts on changing the behavior of individuals. The debate over how far the government should go in protecting the public from health threats is necessarily a debate between competing values. Sullum casts the debate as a struggle between personal freedom and social restraintthe freedom of individuals to choose self-destructive behaviors against societys right to be protected against the costly ignorance, selfish excesses, nuisances and wastefulness of individuals. Viewed in this framework, the utilitarian principle of the most good for the greatest number of people will not resolve the debate, because the definition of good cannot be arbitrated between the value-laden, ambiguous and intangible positions of freedom and of restrained selfishness or excess. The way the political left has framed the debate is as one between victim blaming and system blaming. The left criticizes government for urging individuals to change their health behavior while saying that those same individuals are the victims of corporate exploitation or governmental negligence. The critics on the left, like Sullum on the right, would prefer to see government leave individuals alone; but unlike Sullum they would like to see government take action to protect individuals against corporate advertising and even against the sale of unhealthful products. Further, they would like to see government support individuals and families in order to develop educated, economically secure citizens. A more productive and manageable way to frame the debate is as one between minimal government action (except as needed in response to extreme and imminent danger) and aggressive government action (which would be taken to prevent disease, injury and death as well as to promote health). When framed in this way, the debate can be seen as a choice of degrees rather than as a choice between the irreconcilable and false dichotomies of freedom versus security, fun versus protection and excitement versus safety. These would translate, using Sullums examples, to freedom to bear arms versus gun prohibition, cocktail hour versus drug prohibition and freedom to drive fast cars fast versus prohibition of all cars. These are not the choices governments face. The real decisions governments must make to fulfill their responsibility to protect the publics health in this postbacteriological era are those of how much to promote health actively and how much to protect health passively. The health-promotion approach assumes that individuals will be more resistant to disease and more capable of protecting themselves if they maintain high levels of fitness, of nutrition and of general health knowledge. Accordingly, the health-promotion approach in the United States places

considerable emphasis on educational methods. This education aims to build public awareness, knowledge, motivation, skill and social support for patterns of behavior and lifestyles that will give the American people the maximum ability to resist or defer disease, injury and death. The health-protection approach assumes that individuals cannot count on their own abilities to overcome or resist the forces and temptations that expose them to dangers and so assumes that they must be protected by laws and regulations and by engineered environments and products. Both approaches offer alternatives to the medical-care approach, which waits until damage is done and then seeks to repair it. If a hierarchy of values is to be imposed, the political right would have us set public health policy on the basis of protecting individual freedom above other values and limiting government to an information-only, health-promotion approach. The political left would have us base public health priorities on a hierarchy of human needs, with the need for safety and security to be fulfilled first, the need for nurturing second, and the need for self-actualization third. This would make for policies and programs that would look very different for the poor and for the affluent. Whether derived from political values or from the inescapable recognition that peoples needs vary, a variety or spectrum of health-promotion and health-protection programs can be justified. And that spectrum of programs can be pursued with varying degrees of intensity and urgency with populations at varying degrees of risk. Children and the inner-city poor need public health programs that are different from the programs needed by adults living in affluent suburbs. Sullum correctly cautions the public health community against the medicalization of all human activity and against the narrow-minded assumption that health is an end in itself. But in defending freedom, Sullum fails to acknowledge that children and the poor may not be as capable of protecting themselves and that some personal risk behaviordrunk driving, violent and reckless behavior and smoking in enclosed spaces where others must breathe the same smokethreatens the health of others. In these cases, personal freedom must yield to civil protection. Lawrence W. Green, Dr.P.H., is Director of the Institute of Health Promotion Research and a professor in the Department of Health Care and Epidemiology at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Health Education as Freeing: Developing Decision Makers by Dr. Jerrold S. Greenberg Jacob Sullum raises some important questions for consideration as well as some criticism itself deserving of critical review. I am sympathetic to Sullums criticism of the public health establishment while also believing that his criticism goes a little too far afield. It was almost 20 years ago (1978) that I wrote my article Health Education as Freeing. In it I presented a theory of health education whose purpose was to free people to make their own health decisions as long as those decisions did not adversely and directly affect other people. Sullums view is not too dissimilar. In my article I proposed that people are not initially free to make their own decisions due to enslaving factors: low self-esteem, high alienation, loneliness and social isolation, confused values, an inappropriate locus of control, lack of health knowledge and inadequate health skills. The goal of health education as freeing is to help people escape the limitations imposed on their health-related behaviors by these confining variables. Elaborating on the inappropriateness (and unethical nature) of prescribing healthy behaviors for people and then programming them to behave in these predetermined ways, I then wrote Iatrogenic Health Education Disease (1985). In that article I described the incidental, though no

less meaningful, effects of traditional approaches to educating people about health. I argued that along with any changes in health behavior for which a health education program might claim responsibility, additional, unhealthy effects were also realized. For example, when health education campaigns employ anxiety-arousing methodologies to convince women to perform breast self-examinations, breast cancer may be detected early. The self-examiners incidental state of anxiety is not a healthy one, however. In reality, we have substituted one unhealthy condition for another. Sullum would undoubtedly agree. What Sullum fails to acknowledge, although it would make his argument even more convincing, is that health is more than just physical health. That people should not be free to decide for themselves that a risk to their physical health is worth the benefits to their mental or emotional health is both undemocratic and unethical. Sullum correctly describes it as paternalism. It is the height of arrogance for health educators to believe they can make this decision for people better than people can make this decision for themselves. Im reminded of my wifes decision to refrain from smoking as soon as she learned she was pregnant, only to include a pack of cigarettes in the suitcase she took to the hospital when it came time to deliver. (Those were the days when even hospital oncology wards had smoking lounges!) My wife had determined, with full knowledge of the potential effects of smoking, that the relaxation and enjoyment she obtained was worth the risk to her physical health. She has since come to a different conclusion and no longer smokes; but that, too, was her own decision. Sullum accuses the public health perspective of recognizing one supreme valuehealththat cannot be trumped by other considerations. I would qualify that statement by stating the one supreme value that trumps all other considerations, as well as all other components of health, to be physical health. Now, having said all that and having agreed with Sullums basic premise, let me offer a caveat that recognizes the difference between health education and health promotion. Health education should not be manipulative or coercive. It should have as its goal to help people acquire the information they need to make health-related decisions. This information should include knowledge of their own motivation and other influences on their behavior as well as specific information about health matters (the risks associated with engaging in unprotected sex, for example). The health education goal should not be to change behavior but rather to develop informed decision makers who can then decide for themselves which behaviors to adopt. Health promotion, on the other hand, includes activities designed to create an environment conducive to peoples making health-enhancing choices. Using this conception, government-sponsored advertising encouraging people to refrain from smoking cigarettes might well be an appropriate health promotion or public health endeavor, whereas a government ban on cigarettes might be inappropriate. Requiring that foods be labeled so that consumers can decide to purchase items low in saturated fat or calories is a health promotion activity that allows people to behave healthfully. In conclusion, Sullums criticism has a great deal of validity and should raise a red flag for public health personnel. For a government to predetermine how people ought to behave (that is, in ways that enhance their physical health) and then to engage in activities designed to bring about those behaviors is unethical, undemocratic and not to be tolerated. Yet, public health efforts to create an environment conducive to healthan environment in which people who choose to engage in healthy behavior canis appropriate. In fact, such efforts are not merely appropriate; the public health community would rightly stand accused of negligence should it ignore this responsibility. Jerrold S. Greenberg, Ed. D., is Professor of Health Education at the Department of Health Education, University of Maryland, College Park. He was the recipient of the Association for the Advancement of Health Educations (AAHE) Scholar Award in 1994 and currently serves as the Alliance Scholar of the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance.

References Greenberg, JS. Iatrogenic health education disease. Health Education. 1985;16:46. Greenberg, JS. Health education as freeing. Health Education. 1978;9:2021.

Rights, Ethics and the Question of Lifestyle Factors by Dr. John Higginson The success of an active public health policy over the last century in controlling communicable and occupational diseases is unquestioned. Since World War II, however, public health officials have become increasingly concerned with illnessessuch as cancer, heart disease and AIDSthat have important links to an individuals lifestyle. Jacob Sullums What the Doctor Orders raises important questions in relation to the control of these diseasesquestions about the role of public health and regulation. These questions relate to individual rights, to medical ethics, to politics and to the limits of government. All are important and legitimate matters for discussion in the United States today. In the past, the need to take strong public action for the control of communicable diseases was accepted when taking action was perceived as benefiting the community as a whole. It was accepted even if, in some cases, it hurt the individualas in the case of Typhoid Mary, for example. It was understood that strong public action for the control of communicable diseases benefited the individual in his or her role as member of the community. This concept appears less clear-cut, however, when the direct hurt an individual causes to the community is uncertain and involves legal activities that do not, in the individuals opinion, affect others. In the mid 19th century, Sir John Simon laid the foundation of modern public health policy with his emphasis that a policy should be based on scientific knowledge of a disease and its causation. Simons views were in sharp contrast to those of the SanitariansSir Edwin Chadwick, a lawyer, and Florence Nightingalewho had little use for medical science. Nightingale even commented, There is no need to know, only to do. Recent decades have shown that the same controversy still persists in North America. Historically, political thinking in the United States supports the rights of an individual to make his or her own decisions; but since the days of the pilgrims there has been a tendency for those who believe in the righteousness of their cause to impose it on others. In contrast to communicable diseases, many lifestyle-related diseases have a highly complex background involving factors both exogenous (originating outside the body) and endogenous (originating within the body). Further, these factors are often indirectly influenced by both social environment and genetic makeup. All of these complex factors must be considered by the public health official. Overemphasis, in the 1960s and 70s, on ambient pollutants causing chronic disease led to a downplaying of lifestyle factors. Lifestyle factors were also downplayed on the grounds that they were too difficult to control or understand. That situation has now changed; there is expanding interest in the lifestyle area, with increasing influence on public health practice. But that expanding interest and influence may, unfortunately, go beyond available knowledge. Many lifestyle factors do not lend themselves readily to simplistic control. It may be possible to calculate the benefits of certain changes in lifestyle to a community, but the final outcome to the individual cannot often be stated meaningfully. Only the odds, based on community data, can be

expressed. Many people are aware that not all smokers die from lung cancer or all mountaineers from falls and will accept the known risks of the hazardous activity as important to the individuals enjoyment of life. The role of nutrition in human cancer is poorly understood, but claims as to the benefits of good nutrition to an individual tend to be considerable. There is evidence that most colon cancers may occur in genetically susceptible individuals to whom dietary advice or chemo-prevention may be beneficial; but that course may not be beneficial to others who are less susceptible. The benefits of a lacto-vegetarian diet in childhood may be considerable, with less evidence of benefits to an adult. On the other hand, dietary advice may be targeted to the very obese or to individuals with hypercholesterolemia (the presence of excess cholesterol in the blood). Nonetheless, biomarkers of susceptibility to a potential disease should not be regulated lightly. Rather, they should be handled as a matter of medical practice and ethics. Rightly or wrongly, the role of individual susceptibility is widely accepted; consequently, many individuals have an undue belief in their own invulnerability. These considerations limit the public health official in the attempt to influence individual behavior through traditional regulatory practices. At present, unfortunately, the cost to the community of an individuals illness cannot often be expressed meaningfully. Thus, the prevention of the premature death of an individual from lung cancer or myocardial infarction may only transfer the costs to a later periodat which time the cost to the community may be even higher. Rather, medical ethics requires that the utmost be done to prevent or retard serious disease in an individual. In the final analysis, the position of public health policy in modern society must depend on a rigorous understanding, based on sound medical ethics, of the scientific facts and their uncertainties. The scientific facts must be discussed in the public arena and should not be subjected to hyperbole and misinterpretation on the grounds that the end justifies the means. There is a point at which it is unjustifiable for society to interfere in an individuals life without that individuals wish or consent. The only viable solution would appear to require a defined educational policy regarding diseasea policy free from prejudice and elitism and based on individual freedom and tolerance. In this context Jacob Sullums article makes a notable contribution to the discussion of the numerous issues involved. John Higginson, M.D., F.R.C.P., is Clinical Professor of Community Medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC.

C. Everett Koop: A Surgeon General Speaks Dr. C. Everett Koop, former surgeon general of the United States, was among those asked by Priorities to comment on Jacob Sullums article. Because of his tremendously busy schedule, Dr. Koop did not have the time to write a full-length response; he did, however, graciously agree to respond briefly to three questions we posed to him about the article: Question 1: Does Sullum raise serious questions for you about the role of government in influencing personal health behaviors? The answer is no. I think that the government has a perfect right to influence personal behavior to the best of its ability if it is for the welfare of the individual and for the community as a whole. Most of the behaviors that the government addresses are things that amass huge expenditures not

only for individuals but for the government. For example, smoking costs the nation something like $70 billion every year in direct and associated health costs. I think that this is the governments business. Question 2: In attempting to prevent people from smoking, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, obesity and violence, how well have public health practitioners considered an individuals right to be left alone? I think public health practitioners are aware that they invade privacy; but on the other hand, we have no concern about interfering in the lives of families if they do not send their children to school or about interfering to prevent youngsters from going to school if they have not received the appropriate immunizations against infectious disease. Would any sane person think that it is not the local governments right to intervene in a family where there is spousal or child abuse? I think not. Question 3: What would happen to public health in the U.S. if government got out of the business of attempt ing to influence personal health behaviors? I think you would see a deterioration of the publics health, higher mortality figures and very much increased morbidity. For example, according to the CDC, the antismoking effort between 1964 and 1985 saved $15 billion and several years of life. In my book, that is worthwhile. C. Everett Koop, M.D., is the former Surgeon General of the United States.

The Public Doctor Orders Bad Medicine by Dr. Jane M. Orient Jacob Sullum has the target in his sights, but he doesnt quite hit the bulls-eye. Instead of focusing on what he says (which is well worth reading), Id like to look for what his article misses: the signs that the public health establishment is partly responsible for our problem. The public (i.e., governmental) contribution must be kept in perspective. Most of the credit for the suppression of infectious disease belongs to the individuals who gave us the tools: the germ theory, smallpox vaccination, penicillin and mosquito control. As often as not, the individuals had a constant uphill struggle against the establishment, both governmental and nongovernmental. The most important governmental component to public health is better called sanitation. Additionally, traditional public health has had an important impact in tracking and treating venereal disease and tuberculosis. As the authorities now mobilize against lifestyle-induced epidemics such as smoking and obesity they are diverting resources from traditional public health or are actually impeding its efforts. Few public health departments are using proved methods (such as contact tracing) in combating todays most important sexually transmitted disease, AIDS. Instead, they pass out condoms in the public schools. The limited effectiveness of this method is not enough to compensate for the increased promiscuity that the same programs help to promote. Still worse, the war against metaphorical epidemics that cause only hypothetical deaths is disarming the sanitarians. Real foodborne disease occurs because we fear radiation more than pathogenic bacteria. Worry about chlorine-containing chemicals could deprive us of our most economical and effective disinfectants and result in a surge in diseases such as cholera. The ill-advised ban on DDT has already caused millions of deaths due to malaria in the Third World. It is in the moral arena, however, that public health has had its most baleful effect. As Sullum notes, unhealthy behavior (behavior that used to be called immoral) is a major contributor to

current morbidity and mortality. Many agree with John Knowles that the cost of such behavior has now become a national, rather than an individual responsibility. Both Knowles and (apparently) Sullum have got it backwards. First the government relieved individuals of the responsibility for the costs of their own choices. It created taxpayer-funded or subsidized safety nets, including medical insurance and welfare. Now the government is trying to constrain the resultant, predictable increase in misbehavior. The public health model doesnt work well for this purpose; and, moreover, it eventually leads to totalitarian government, as Sullum correctly notes. But he doesnt follow his own logic to the obvious conclusion: We should stop allowing individuals to impose the cost of their decisions on the rest of us. Actually, Sullum doesnt quite reach a conclusion at all, though he does come to a startling end. After eight pages of complaints about government meddling, the last sentence in his article calls freedom the most important risk factor for disease and injury. Abolishing this risk factor doesnt work either. Totalitarian regimes have far higher rates of disease and injury than free nations, with gunshot wounds being especially prevalent because freedom cannot be totally suppressed without the brutal use of force. The answer eludes Sullum, though he does come tantalizingly close. Long before humankind discovered modern medicine, physicians recognized that virtue (as in prudence, chastity, and moderation) was important for preserving health. Sullum states that the public health establishment seeks government power to impose its vision of virtue on the rest of America. But the public health establishment doesnt know what virtue is. If it did, it would know that virtue can never be imposed. While shunning talk of morality, the government is trying to impose its vision of health. Meanwhile, it thwarts its own stated goals by subsidizing vice with funds extracted by force from productive and virtuous citizens and by shackling the individual enterprise that finds solutions. Jane M. Orient, M.D., is an internist in private practice in Tucson, AZ, and Executive Director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons.

Sound Epidemiology and the Human Condition Equation by Dr. R.T. Ravenholt Among Jacob Sullums many criticisms of public health actions aimed at the amelioration of a wide range of social ills is the following statement, in which his faulty knowledge of both basic human motivation and public health imperatives is capsulized: First of all, behavior cannot be transmitted to other people against their will. Where has Sullum been in the long years during which America has been battling the drug lords (and especially the cigarette purveyors)? These lethal lords of misrule have, through advertising and drug pushing, created vast armies of addictsunwilling slaves to their addictions who must pay out enormous sums to their slave masters and who often are compelled to rob and kill to raise the money. Sullum needs to recognize that the use of any addictive substance is fully dependent upon the availability of that substance, and that the greater or lesser availability of every addictive substance is determined by social policiesby social actions of either commission or omission. No selfrespecting nation or public health program that wants to protect its population from the ravages of addiction can ignore the fundamental task of controlling the availability of substances that greatly

injureeven destroyusers and their associates. John Shaw Billings, a great leader in the field of public health from the Civil War era until his death in 1913, devoted much attention to the prevention of infectious diseases because they were then the foremost killers. But Billings was also a leader in the investigation and control of alcoholthen available mainly as ginduring the first decade of this century. Throughout his professional career Billings demonstrated a broad and active interpretation of the constitutional imperative to provide for the general welfare. No doubt he would have become a leader in the social action to prevent and abate the 20th-century pandemic of tobaccosis had he been aware of the powerful pathogenicity of tobacco. He surely would not have tolerated the continued promotion of tobacco had he been able to foresee its present-day killing of at least half a million Americans annually. In creating the nuclei of both the National Library of Medicine and our modern system for indexing medical-science literature, Billings provided a basis for much of the subsequent advancement of scienceadvancement that has defined todays foremost public health challenges. Although the science of epidemiology was initially concerned with epidemics of infectious disease, the meaning of the word itself was long ago broadened to encompass unusually great occurrences of any sort of disease in human populations. It is so defined in modern dictionaries. Sullums reluctance to accept this broader definition indicates a lack of familiarity with epidemiologythe essential science guiding public health practice. Sullums distaste for many current public health programs is understandable. Many such programs, although initially well intended, are so clumsily fashioned and so poorly implemented that they are deserving of both criticism and deletion. Public health programs must be guided by sound epidemiologyand those in charge of the programs must have outstanding leadership skillsif the programs are to accomplish their intended tasks. Most importantly, the scientific basis for any public health action must be well established before massive programs are launched. This has not been the case for recent programs aimed at the reduction of cholesterol levels, obesity, breast cancer, prostate cancer and Alzheimers disease. Good intentions are an insufficient basis for the creation and continuation of public health programs. Appropriate public health programming proceeds somewhat like the peeling of an onion: As each task is accomplished, another priority task is revealed. Thus, in Billingss time the most urgent task was the prevention of mortality through infectious disease. But when death rates were greatly lowered, there inevitably followed the need to limit fertility to allow populations to thrive and enjoy their longer lives. This is in accord with the Human Condition Equation: Resources divided by Population equals the Human Condition. Death control without simultaneous birth control brings calamitous increases in poverty, starvation, environmental degradation, warfare and social disintegrationas can be seen in many African countries today. During this century the technology for controlling fertility has been vastly improved, and family-planning programs have become an essential and important component of public health practice both at home and abroad. By making effective means of fertility control readily available to impoverished populations, governments around the world have greatly reduced fertility without decreasing personal freedom. Rather, these fertility-control programs have vastly increased sexual freedom while protecting women, men and families from the many disastrous consequences that in the past often attended the attainment of sexual satisfaction. Although unwanted pregnancy is not generally classified as a communicable disease, it surely is a profound cause of dis-ease for the women so afflicteda condition communicated to them by sexual intercourse and, in less developed countries, one that often results in death. R.T. Ravenholt, M.D., M.P.H., is President of Population Health Imperatives, Seattle, WA.

Jacob Sullum Responds to the Commentaries on What the Doctor Orders Although Lawrence W. Green assumes I belong there, I do not consider myself on the right. Like Wilhelm von Humboldt and John Stuart Mill, the two troublesome classical liberals with whom John S. Billings contended, I believe the proper role of government is to protect peoples rights. Most traditional public health measures, including nuisance laws, pollution control and restrictions on disease carriers, are compatible with this mission. They are intended to protect people from external threats to their health. By contrast, many contemporary public health policies, including seat-belt laws, alcohol taxes, and restrictions on cigarette advertising, are intended to protect people from themselves. Such measures violate peoples rights rather than defending them. As Mill put it, the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. While its probably true that public health specialists tend to be left of center, conservatives have been happy to use public health rationales in support of policies they favor, including bans on prostitution, abortion and certain drugs. When it comes to protecting people from themselves, the important division is between individualists and collectivists of the left and right, not between liberals and conservatives or Democrats and Republicans. C. Everett Koop, Ronald Reagans surgeon general, provides a nice illustration of this point. Dr. Koop seems to have no reservations whatsoever about government efforts to improve the publics health. He says the government has a perfect right to influence personal behavior to the best of its ability if it is for the welfare of the individual and for the community as a whole. (Emphasis added.) This is paternalistic tyranny in its purest form, assigning government the authority to judge the welfare of the individual and elevating the community as a whole above mere people. Dr. Koop compares efforts to deter individuals from smoking, drinking or overeating to laws against assault. He thus ignores the crucial distinction between self-regarding behavior and behavior that violates other peoples rights. Dr. Koop resorts to the familiar argument that people who do unhealthy things impose costs on others. But third parties are forced to bear such costs only when the government makes them, through programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Even then, lifestyle related diseases and injuries do not necessarily represent a net drain on taxpayers, since people who die early take less Social Security and consume loss health care in old age. In any case, as Jane M. Orient notes, anyone who supports government subsidies for health care also supports subsidies for risky behavior. Like Dr. Koop, R.T. Ravenholt sees no cause for concern in the ever-expanding public health agenda. Although the science of epidemiology was initially concerned with epidemics of infectious disease, he writes, the meaning of the word itself was long ago broadened to encompass unusually great occurrences of any sort of disease in human populations. In fact, as I show in my article, it has been broadened to encompass not just noninfectious disease (along with injuries) but behavior associated (or thought to be associated) with an increased risk of disease or injury. That expansion has been proceeding for many years, but it has not been without controversy, as the debate in the early 1970s about applying epidemiology to drug abuse illustrates. Dr. Ravenholt suggests that by questioning this trend, I demonstrate faulty knowledge and a lack of familiarity with epidemiology, By the same line of reasoning, anyone who objects to the size of the national debt demonstrates a lack of familiarity with fiscal policy, since it has been growing for some time now. I reject Dr. Ravenholts casual equation of addiction with slavery. Drug sellersincluding Starbucks, Philip Morris, Seagrams and the local cocaine, marijuana, or heroin dealerdo not force people to buy or consume drugs. People buy and consume drugs because they want to. This does not mean that people never use drugs inappropriately or excessively, or that they never regret their drug use, or that they never have difficulty stopping. But such problems are not unique to psychoac-

tive chemicals. Almost any source of pleasureeating, sex, gambling, exercisecan become the focus of a self-destructive habit that is hard to break. To call such behavior slavery relieves people of responsibility and strips them of their dignity. Dr. Ravenholt says John S. Billings demonstrated a broad and active interpretation of the constitutional imperative to provide for [sic] the general welfare. But Billings seems to have had a bit more respect for constitutional limits than Dr. Ravenholt implies. In A Treatise on Hygiene and Public Health, he noted that the 10th Amendment reserves the police power, including public health regulations, to the states, and Congress has no authority to act in this area. It is possible that in the future a constitutional amendment may confer upon Congress the necessary authority, to prescribe and enforce measures for the preservation of the public health, he wrote, but at present we can only look to the action of the individual states. Unlike Drs. Koop and Ravenholt, most of the commentators seem to agree that the overzealous pursuit of public health represents a threat to individual autonomy. Philip Cole is especially eloquent on this point. The consensus appears to be that public health could use a little more balance and moderation. That is encouraging as far as it goes, but it is also worrisome. I picture a bunch of technocrats weighing the costs and benefits of each policy (including, of course, its impact on individual freedom) and deciding whether its justified: cigarette ban, no; handgun ban, yes; fat tax, no; helmet law, yes. If the government gets to decide, on a case-by-case basis, when the needs of society override individual rights, those rights are not very meaningful, I am also troubled by some of the rhetoric employed by the moderates. Jerrold S. Greenbergs concept of enslaving factors, for example, implies that people are not really free if they suffer from low self-esteem, high alienation, loneliness and social isolation, confused values, an inappropriate locus of control, lack of health knowledge [or] inadequate health skills. This suggests that their decisions need not be respected until somebody (the government?) brings them up to speed. Similarly, Mr. Greens comment that children and the poor may not be as capable of protecting, themselves seems to put adults below a certain income level in the same category as children. It is natural to conclude that people who make choices different from ours are foolish, short-sighted or poorly informed. The problem arises when we ask government to act on that assumption.

The Reason Letters The following letter from ACSH was printed, along with Jacob Sullums response, in the April issue of Reason. The exchange ran under the heading Healthy Debate: Jacob Sullums What the Doctor Orders (January), the most important critique of governmental public health activities we have seen, should be assigned reading in every school of public health. We plan (with Reasons permission) to reprint Mr. Sullums article in a special issue of our health magazine, Priorities, along with commentaries from several public health leaders and, hopefully, a rejoinder by Mr. Sullum. We think the special issue will encourage public health activists to consider the extent to which government health promotion programs can both threaten and enhance individual liberty. We concur with Mr. Sullum that people engage in various health-compromising behaviors for pleasure, utility, or convenience. However, we dont think this means people, especially children, are necessarily prepared to accept the risks associated with their lifestyles. People tend to succumb to

social pressure and impulse in adopting health-compromising lifestyles and then justify their actions by rationalizing about them. This is hardly the libertarian ideal of self-directed, reasoned decision making. Choices made by neglecting likely negative consequences may give some people a sense of freedom, but how free can someone be who chooses chronic self-destruction? Educational initiatives that deemphasize mere propaganda and help people learn to make carefully reasoned lifestyle choices may offer more genuine personal freedom than is provided by the simple opportunity to indulge in bad habits without government interference. For example, national dialogue about Surgeon Generals reports on smoking has led tens of millions of Americans to modify their lifestyles and improve their lives. Would Americans actually feel more free or live more fully if government stopped addressing lifestyle and health issues altogether? William M. London Director of Public Health Elizabeth M. Whelan President American Council on Science and Health New York, NY Jacob Sullum responds: I thank Mr. London and Ms. Whelan for their kind remarks, but I have to say that their notion of freedom gives me the willies. In a free society, individuals constantly make choices that seem foolish or short-sighted to observers with different tastes and preferences. Personally, I do not perceive enough benefit in smoking to justify the risk. But Im sure a lot of smokers would have a hard time understanding why I enjoy bungee jumping. By saying that individuals who defend their health-compromising lifestyles are simply rationalizing, Mr. London and Ms. Whelan imply that such choices are inherently irrational and that people who make them must be ignorant, stupid, or crazy. Its true that people sometimes regret decisions to engage in risky behavior. People make mistakes in every area of life. In this respect, the smoker with lung cancer resembles the woman who spends her life in a loveless marriage or the retiring CPA who wishes he had become an airline pilot. All three have made decisions that were hard to reverse, with consequences that are now permanent. If people are free only to make careful, reasonable, fully considered choices that they will never regret, they are not free at all. Reprinted with permission from the April 1996 issue of Reason Magazine. Copyright 1996 by the Reason Foundation, 3415 S. Sepulveda Blvd., Suite 400, Los Angeles, CA 90034.

You might also like

- Nicotine Release Jan 2014Document1 pageNicotine Release Jan 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Concussions: Fact v. FictionDocument34 pagesConcussions: Fact v. FictionAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Nicotine Release Jan 2014Document1 pageNicotine Release Jan 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Does 'Excess' Dietary Salt Cause Cardiovascular Toxicity?Document29 pagesDoes 'Excess' Dietary Salt Cause Cardiovascular Toxicity?American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

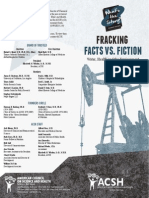

- Fracking Press Release June 13 2014Document1 pageFracking Press Release June 13 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Priorities March 2016Document20 pagesPriorities March 2016American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- What's The Story? Fracking: Facts vs. FictionDocument4 pagesWhat's The Story? Fracking: Facts vs. FictionAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- GM Press Release March 2014Document1 pageGM Press Release March 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- GM Press Release March 2014Document1 pageGM Press Release March 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Top 13 Scares in 2013Document23 pagesTop 13 Scares in 2013American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Sugar Substitutes & Your HealthDocument36 pagesSugar Substitutes & Your HealthAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Fracking and Health: Facts vs. FictionDocument35 pagesFracking and Health: Facts vs. FictionAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- What's The Story: Genetically Modified FoodDocument4 pagesWhat's The Story: Genetically Modified FoodAmerican Council on Science and Health100% (1)

- Fracking Press Release June 13 2014Document1 pageFracking Press Release June 13 2014American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Food and You: A Guide To Modern Agricultural BiotechnologyDocument109 pagesFood and You: A Guide To Modern Agricultural BiotechnologyAmerican Council on Science and Health100% (1)

- Hydraulic Fracturing in The Marcellus Shale: Water and Health, Facts Vs FictionDocument41 pagesHydraulic Fracturing in The Marcellus Shale: Water and Health, Facts Vs FictionAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- Food and You: Feeding The World With Modern Agricultural BiotechnologyDocument36 pagesFood and You: Feeding The World With Modern Agricultural BiotechnologyAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Nicotine On Human Health - Consumer VersionDocument27 pagesThe Effects of Nicotine On Human Health - Consumer VersionAmerican Council on Science and Health100% (6)

- Nicotine and HealthDocument82 pagesNicotine and HealthAmerican Council on Science and Health100% (9)

- ACSH Holiday Dinner MenuDocument12 pagesACSH Holiday Dinner MenuAmerican Council on Science and Health75% (4)

- Donate Wisely: Get To Know Your Breast Cancer Organizations During BCA MonthDocument46 pagesDonate Wisely: Get To Know Your Breast Cancer Organizations During BCA MonthAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- ACSH Presents: Celebrities vs. ScienceDocument10 pagesACSH Presents: Celebrities vs. ScienceAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- ACSH Media Update, July-December 2012Document40 pagesACSH Media Update, July-December 2012American Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- The Mentholation of Cigarettes: An Update For 2013Document38 pagesThe Mentholation of Cigarettes: An Update For 2013American Council on Science and Health0% (1)

- ACSH Holiday Dinner MenuDocument12 pagesACSH Holiday Dinner MenuAmerican Council on Science and Health75% (4)

- Response To NY Post ArticleDocument3 pagesResponse To NY Post ArticleAmerican Council on Science and HealthNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Standards in Social Work Practice Meeting Human RightsDocument40 pagesStandards in Social Work Practice Meeting Human RightsifswonlineNo ratings yet

- The Age of IdeologyDocument217 pagesThe Age of IdeologyAhmed Laheeb100% (1)

- Congressional Report 2013Document320 pagesCongressional Report 2013Anonymous aVa96ZzNo ratings yet

- POLITICAL SPECTRUM: LEFT VS RIGHTDocument8 pagesPOLITICAL SPECTRUM: LEFT VS RIGHTMuthu SrinithiNo ratings yet

- An Historical Essay On Modern Spain: Richard Herr Spain Splits in TwoDocument10 pagesAn Historical Essay On Modern Spain: Richard Herr Spain Splits in TwoMohamed BouykorranNo ratings yet

- Vietnam War Memorial Book ReviewDocument4 pagesVietnam War Memorial Book ReviewIgor CostaNo ratings yet

- Turner - Contemporary Problems in The Theory of CitizenshipDocument18 pagesTurner - Contemporary Problems in The Theory of CitizenshipAnonymous n4ZbiJXj100% (1)

- Alan Scott - New Critical Writings in Political Sociology Volume Three - Globalization and Contemporary Challenges To The Nation-State (2009, Ashgate - Routledge) PDFDocument469 pagesAlan Scott - New Critical Writings in Political Sociology Volume Three - Globalization and Contemporary Challenges To The Nation-State (2009, Ashgate - Routledge) PDFkaranNo ratings yet

- The failure of third world nationalismDocument12 pagesThe failure of third world nationalismDayyanealosNo ratings yet

- The FascismDocument7 pagesThe FascismJasmuneNo ratings yet

- Deudney - Who Won The Cold War?Document10 pagesDeudney - Who Won The Cold War?ColdWar2011No ratings yet

- Legal Status of NLMsDocument84 pagesLegal Status of NLMsCront CristiNo ratings yet

- Bob Altmeyer - The AuthoritariansDocument261 pagesBob Altmeyer - The Authoritarianszoidbergh77No ratings yet

- Democracy and National Identity in Thailand by Michael Kelly Connors (Only 6 - Citizen King)Document25 pagesDemocracy and National Identity in Thailand by Michael Kelly Connors (Only 6 - Citizen King)sachatoiNo ratings yet

- Noam Gidron. Bart Bonikowski. Varieties of Populism: Literature Review and Research AgendaDocument39 pagesNoam Gidron. Bart Bonikowski. Varieties of Populism: Literature Review and Research Agendajorge gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Remember Mississippi Grassroots Letter #MssenDocument4 pagesRemember Mississippi Grassroots Letter #MssenRuss LatinoNo ratings yet

- The Political CompassDocument1 pageThe Political CompassgarfieldNo ratings yet

- 2015 House of Reps Candidates (Federal)Document160 pages2015 House of Reps Candidates (Federal)abhi_akNo ratings yet

- Visser - Fascist Doctrine and The Cult of RomanitaDocument19 pagesVisser - Fascist Doctrine and The Cult of RomanitaacqualucaNo ratings yet

- The Old Struggle For Human Rights, New Problems Posed by SecurityDocument5 pagesThe Old Struggle For Human Rights, New Problems Posed by SecuritypopbiloNo ratings yet

- M&W Wave Patterns - Arthuer A. Merrill - 1980Document12 pagesM&W Wave Patterns - Arthuer A. Merrill - 1980Sri Ram80% (5)

- Anti Discrimination BillDocument5 pagesAnti Discrimination BillMurphy RedNo ratings yet

- Brubaker Triadic Nexus Theory and Critique Quadratic NexusDocument14 pagesBrubaker Triadic Nexus Theory and Critique Quadratic NexusCharlène AncionNo ratings yet

- Parlamentarni Izbori 2007 RezultatiDocument13 pagesParlamentarni Izbori 2007 Rezultatigfc123No ratings yet

- Treasury CEO Talking PointsDocument177 pagesTreasury CEO Talking PointsZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- AP Comp Gov Study GuideDocument42 pagesAP Comp Gov Study GuideHMK86% (7)

- History of Human Rights ExploredDocument4 pagesHistory of Human Rights ExploredLuis EchegollenNo ratings yet

- Declaration On Social Progress and Development, G.A. Res. 2542 (XXIV), 24 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 30) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/7630 (1969)Document12 pagesDeclaration On Social Progress and Development, G.A. Res. 2542 (XXIV), 24 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 30) at 49, U.N. Doc. A/7630 (1969)api-234406870No ratings yet

- Derechos de Participación, Realidad o RetoricaDocument301 pagesDerechos de Participación, Realidad o RetoricaChipelibreNo ratings yet

- 09 Usp Ch01 Important Questions The French RevolutionDocument12 pages09 Usp Ch01 Important Questions The French RevolutionManish Thakur0% (1)