Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rowe Entertainment, Inc. Et Al. v. William Morris Agency, Et Al. (98-8272) - Plaintiffs' Opp. Attorneys Fees and Costs (May 9, 2005)

Uploaded by

Mr Alkebu-lanOriginal Title

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Rowe Entertainment, Inc. Et Al. v. William Morris Agency, Et Al. (98-8272) - Plaintiffs' Opp. Attorneys Fees and Costs (May 9, 2005)

Uploaded by

Mr Alkebu-lanCopyright:

Maria Sperando, Esq. W i l l i a m C. Campbell, Esq. GARY, WILLIAMS, PARENTI, FINNEY, L E W I S , McMANUS, W A T S O N & S P E R A N D O , P.L. 221 E.

Osceola Street Stuart, PL 34994 Tel: (772)283-8260 Fax: (772)283-4996 ' Attorneys for Plaintiffs Rowe Entertainment, Inc., et al.

#72/

r

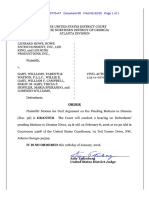

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OFNEW Y O R K n ;

R O W E E N T E R T A I N M E N T , INC., et a l . Plaintiffs,

vs.

N O . 98-CV-8272 (RPP)

<

T H E W I L L I A M M O R R I S A G E N C Y , INC. et al., Defendants

' -

R E S P O N S E IN OPPOSITION O F T H E P L A I N T I F F S AND T H E G A R Y F I R M T O T H E D E F E N D A N T S ' M O T I O N S F O R A T T O R N E Y S ' F E E S AND C O S T S

GARY, W I L L I A M S , PARENTI, FINNEY, L E W I S , MCMANUS, WATSON & SPERANDO, P.L. WATERSIDE PROFESSIONAL BUILDING 221 East Osceola Street Stuart, Florida 34994 (772) 283-8260 Attorneys for Plaintiffs

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW Y O R K

R O W E E N T E R T A I N M E N T , I N C . , et al.. Plaintiffs, vs THE WILLIAM MORRIS AGENCY, LNC, et al., Defendants. R E S P O N S E I N O P P O S I T I O N O F T H E P L A I N T I F F S AND T H E G A R Y F I R M T O T H E D E F E N D A N T S ' M O T I O N S F O R A T T O R N E Y S ' F E E S AND C O S T S Plaintiffs, by and through their undersigned attorneys, and Gary, Williams, Parenti, Finney, Lewis, McManus, Watson & Sperando, P.L. ("the Gar>' Firm"), hereby respond i n opposition to the Motions For Attorneys' Fees and Costs o f Creative Artists Agency ( " C A A " ) , W i l l i a m M o m s .Agency ( " W M A " ) , and Renaissance ("the B . A . Defendants"), Beaver and Jam.' I M P O S I T I O N O F S A N C T I O N S P U R S U A N T T O 1988. 1927. T H E C O U R T ' S I N H E R E N T P O W E R O R R U L E 11 W O U L D B E A N A B U S E O F D I S C R E T I O N B E C A U S E DEFENDANTS H A V E NOT P R O V E N T H A T PLAINTIFFS' C I V I L R I G H T S C L A I M S W E R E F R I V O L O U S O R L I T I G A T E D IN B A D FAITH.^ Only taur important corrections as to the Defendants' legal arguments are necessary. First, 1988 permits the recovery o f attorney's fees to a prevailing defendant in a 1981 action "only where the suit was vexatious, frivolous, or brought to harass or embarrass the defendant." Henslev v. 98 C i v . 8272 (RPP) ORAL ARGUMENT REQUESTED

Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424, 429 n. 2, 103 S. Ct. 1933 (1983). Second, t h c B . A . Defendants admit that a

The Plaintiffs and the Gary Firm incorporate by reference and rely upon Robert E. Donnelly's Response and all evidence submitted in this case. 'The Gary Firm filed its Notice of Appearance on July 23, 2001, attended about 20 of the approximately 62 depositions taken, and responded to the Motions to Exclude Jaynes and Feagin and Motions for Summary Judgment, and submitted the following docket entries: 352, 421, 428, 430, 440-42 451-57, 462, 465, 468, 476-81, 483, 486-89, 503, 510, 511, 520-22, 524, 525, 531-34, 534, 536, 537, 539, 552, 554, 563-65, 567-70, 572, 580, 581, 585, 597, 598, 605-53, and 655-71. (See Aff. of Mana Sperando, f^9-14, 18, 20, Ex.1.)

-1-

finding of bad faith is necessary to impose fees pursuant to 1927, but they erroneously claim, relying on United States v. Seltzer. 227 F. 2d 36, 41 -42 (2d Cir. 2000), that this Court may impose sanctions under its inherent powers even absent bad faith under these circumstances. Seltzer, the court held: W^en a district court invokes its inherent power to impose attorney's fees or to punish behavior by an attorney i n 'the actions that led to the l a w s u i t . . . [or] conduct o f the litigation,' [citation omitted], which actions are taken on behalf o f a client, the district court must make an explicit finding o f bad faith. [Citations omitted.] . . . But, when the district court.. . sanction[s] misconduct. . .that [violates] a court order or other misconduct that is not undertaken for the client's benefit, the district court need not fmd bad faith before imposing a sanction . . . . Id. at 41-42 (emph. added). Thus, since the attorneys' conduct at issue concerns only conduct o f the litigation for the benefit o f the clients, an explicit finding o f bad faith is required. Third, Beaver, the only Defendant to request Rule 11 sanctions (B.Memo. 9), violated Rule 11(c) (1)(A) because it made its Rule 11 motion for the Plaintiffs' response to its motion for summary judgment after its motion for summary judgment was decided, thereby not allowing the Plaintiffs an opportunity to withdraw their response. Beaver cannot rely on its Dec. 3, 2002 letter to Ray Heslin because that was before the Plaintiffs filed their response to the motion for summary judgment, i.e., long after the 21 day "safe harbor" period had passed. See Hutchinson v. Pfeil. 208 F. 3d 1180, 1183-84 (10th Cir. 2000) ("as the [Rule 11] motion was filed subsequent to summary j u d g m e n t , . . . reliance on Rule 11 would have . . . [violated] rule's twenty-one day 'safe harbor' provision"). Fourth, "[t]he fact that a plaintiff may ultimately lose his case is not i n itself sufficient justification for the assessment o f fees." Hughes v. Rowe. 449 U.S. 5,14,101 S. Ct. 173,178 (1980). The Court's warning m Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412, 421, 98 S. Ct. 694, 700 (1978), not to conclude that "because a plainfiff did not ultimately prevail, his action must have been (B.A. Memo. 21.)-^ In

'The memoranda of the B.A Defendants, Beaver and Jam will be referred to as "B.A. Memo.," "B.Memo." and "J. Memo." The Court's Final Opinion will be referred to as ( .) The transcripts of the hearings on Apnl 11, 2000, May 6, 2003, Oct. 16, 17, and 20 will be referred to as " T l , " ' T 2 , " "T3," "T4," and "T5." .All cited hearing transcript pages are attached as Ex. 2. A l l cited deposition transcript pages are attached as Ex. 3. -2-

unreasonable or without foundation," "is particularly pertinent to cases involving allegations o f conspiracy " Le Blanc-Stemberg v. Fletcher, 143 F.3d 765, 770 (2d Cir. 1998). Some o f the reasons which prove that the Plaintiffs' claims as to all Defendants were not vexatious, frivolous, or made in bad faith are as follows:'' 1) Harvard Law Prof. Charles Ogletree has concluded that the Plaintiffs' claims were not frivolous, vexatious or made i n bad faith. (Charles Ogletree Aff.^^5-8; Ex. 4.) Prof Ogletree mediated this matter between the Plaintiffs and SFX, and was counsel for A l Haymon in this matter, and thus is very familiar w i t h the facts, the parties and their attorneys. (Id. ^3,4.) 2) SFX, the largest promoter i n the

country, settled the claims against it.' This eviscerates Jam's and Beaver's claim that promoters had no place i n this lawsuit.* 3) Monterey Peninsula and the Howard Rose Agency, settled as well (for

amounts the Plaintiffs may not reveal). (Sperando Aff. f 23.) Thus, although the B. A. Defendants allege

''The Plaintiffs in good faith initiated and prosecuted tills action (Leonard Rowe Aff. f 10-12, Ex. 5; Jesse Boseman A f f f4, Ex. 6, Lee King A f f 14, Ex. 7, Fred Jones AiY. Ex. 8.) That the Plaintiffs' claims were neither frivolaus nor pursued in bad faith is supported by their appellate brief which is incorporated herein by reference and will be filed with this Court upon its completion. ^Jam's contention that this agreement is cause for the imposition of sanctions against the Plaintiffs and their counsel is baseless. The SFX agreement had nothing to do with the Plaintiffs' decision to continue to litigate against Jam. First, the Plaintiffs never intended to setde with Jam for less than $1,000,000, and thus making that a condition of the settlement with SFX was meaningless because it did not require the Plaintiffs to do anything they had not already decided to do. (Rowe A f f . f 9, Willie Gary A f f t1[4,5, Ex. 9.) Second, the Plaintiffs continued to litigate against Jam for the same reason they continued to litigate agamst Beaver and the B. A. Defendants to whom the SFX agreement did not apply, i.e.. Jam never offered an amount to settle that was sufficient to compensate the Plaintiffs for the harm Jam had done to them. (Rowe Aff. f 9; Gary A f f ^6.) Third, Plaintiffs' counsel offered to settle with Jam for less than $1,000,000, contingent on the Plaindffs' approval, but Jam offered only far less than that. (Gary A f f ^6.) Rowe has reconfirmed that he never would have settled with Jam for less than $1,000,000. (Rowe A f f ^9.) Finally, the provision at issue is analogous to a "most favored nations" clause which is "an unconditionally worded clause that prohibits plaintiffs from making a later settlement with remaining defendants on terms more favorable than the settlement plaintiffs made with an earlysettling defendant, without giving the early-settling defendant a refund to equalize the earlier and later settlements." Fisher Bros, v. Phelps Dodge hidustries. Inc., 614 F. Supp. 377, 382 (E.D.Pa. 1985). However, the settlement at issue here did provide for a refund. ^This setUement also invalidates Haymon's presuit opinion that promoters should not have been included as defendants and cuts against the Court's conclusion that "Jam and Beaver were purchasers of artist talent," and, therefore, could not have taken actions to prevent Plaintiffs from doing the same. (64.) See Section 2.2 of the settlement agreement. See also Leff letter and transfer of James Taylor concert infra at 15-16. Moreover, the SFX setUement is additional evidence that the Plaintiffs' case against the B.A. Defendants was not frivolous because SFX could not have engaged in a conspiracy by itself -3-

that the claims against the agency Defendants were frivolous, two agency Defendants disagreed. 4) Beaver has acknowledged that the Plaintiffs' claims against the Agency Defendants were supported by "at least . . . some evidence as per the deposition o f Alan Haymon." (Ex. 10.) 5) The Defendants deposed each of the Plaintiffs for four days, 16 days i n total, belying their contention that the Plaintiffs' claims were fHvoIous. 6) Defendants allege they had to incur SI 1,379,792 i n fees and costs (including the 25% in unrecoverable fees deducted by the B. A . Defendants) to defend this action. See Bynum v. Michigan State Univ.. 117 F.R.D. 94, 102 n. 3 (VV.D. Mich. 1987) ("court can't help noting the irony that it apparently took defense counsel $19,000.00 worth of billable legal time to prepare a motion and brief to dismiss a suit they now characterize as 'frivolous and groundless'"). 7) This Court's 174-page opinion, rendered after an intensive review o f 15 months' duration, alone proves that Plaintiffs' claims were "definitely not meritless i n the Christiansburg sense." Hughes. 449 U.S. at 15, 16 n. 13, 101 S. Ct. at 179, 179 n. 13 ("[a]s Judge Swygert noted . . . the District Court dismissed petitioner's claims only after detailed consideration resulting in a seven-page opinion. According to Judge Swygert: ' I t is quite evident from the detailed treatment given by the district court to the issues raised by p l a i n t i f f s complaint that the suit was not groundless or meritless. The fact is corroborated by this court's treatment o f the same issues on appeal.) 8) The briefs, Rule 56.1 Statements, and exhibits total thousands o f pages. As this Court noted, "[w]e have a full table o f documents . . . stacked up two feet high." (T4:22.) 9) The parties took two and a half days to argue the summary judgment motions on the Plaintiffs' so-called "frivolous" claims. 10) This Court, when the motions to dismiss the Amended Complaint were heard, tried to encourage both sides to settle this matter. ( T l :4, 6.) A t the summary judgment hearing, after the Court had read the motions and responses, this Court again encouraged both sides to settle, stating, " . . .1 still can see ways i n which there could be some change i n the way o f conducting business. It seemed to me that would be beneficial to the plaintiffs.* * * I still think it

should be settled.. . ." (T4:42, emph. added.) Presumably, this Court would not have encouraged the parties to settle, especially as late i n the case, had it thought that the Plaintiffs' claims were frivolous

.4.

or brought in bad faith. That by itself establishes that the claims were not frivolous. Moreover, the Court's persistence in encouraging settlement caused the Plaintiffs and their attorneys to believe that this Court believed that the Plamtiffs had valid claims (Sperando Aff. f 5; Boseman A f f ^5; Jones Aff. f 5 ; K i n g Aff. ^jS), and that, therefore, the case would be tried. (Id.) 11) CAa^. itself claimed an interest in settling what i t now claims is a "frivolous" case. Jeffrey Kessler, counsel for C A A , stated on A p r i l 11, 2000, "we remain interested i n having settlement talks and mediation i n any alternative that your Honor would suggest." ( T l : 4, emph. added.) Subsequently, the B . A . Defendants did voluntarily mediate this case, but the parties were unable to agree on an amount. (Sperando Aff. ^22.) 12) This Court, responding to argument that Plaintiffs had not pled a conspiracy, stated, "[mjaybe you fellows aren't part o f something, but certainly someone else seems to have been monkeying around with trying to exclude [the Plaintiffs] [from promoting white a c t s ] . . . . It may not cover a conspiracy claim with respect to that particular act with respect to your particular clients, but the allegations about what other people d i d seem to be o f a concerted nature . . . . Not necessarily an antitrust violation, but possibly a civil rights violation." ( T l : 93,94, emph. added.) 13) On May 6,2003, this Court inquired of Plaintiffs' counsel, "[w]ho is going to try this case?"(T2: 89.) The Court also stated, in the context of a discussion concerning the trial, "[y]ou have got to cut this case down." (Id.) A t no time during that (or indeed any) hearing did the Court even hint that the Plaintiffs' claims were frivolous. Cf. Topalian v. Ehrman. 3 F.3d 931, 938 (5th Cir. 1993) (court warned appellants o f possible sanctions so that they had opportunity to desist from objectionable conduct). Although the Court expressed some skepticism w i t h regard to the antitrust claim, it stated that the discrimination claims "require[d] a lot o f detailed work by the Court to deal with . . . " (T3: 37.) In fact, the Court expressly stated, "[w]e have got to get this case to trial." (T2: 101, emphasis added.) Again, the Plaintiffs believed that the Court would not have made these statements i f it had not believed that there was going to be a tnal and that was one o f the reasons that Plaintiffs and their attorneys pressed forward w i t h their claims. (Sperando A f f . ^17; Boseman A f f f 5 ; Jones Aff. ^5; K i n g A f f f 5 . ) Plaintiffs attorneys do not dismiss their lawsuits or

even consider whether they are frivolous when the trial court speaks about having to "get this case to trial." (Sperando Aff. fS.) Given the Court's encouraging the parties to settle, and its pronouncements about trying the case, the possible validity o f the discrimination claims, and the probability o f racism i n the music promotion industry (T5:231), both Plaintiffs and their counsel were stunned when the Court granted summary judgment on behalf o f all Defendants. (Sperando A f f f 8 ; Boseman A f f ^6, K i n g A f f ^6, Jones A f f f 7.) 14) This Court also made numerous statements which a reasonable person could have interpreted, and the Plaintiffs did so interpret (Sperando A f f f 5), as being an indication from the Court that the case was not frivolous and that it likely would be tried. Specifically, regarding the contention that the Plaintiffs had failed to put forth an economically plausible theory "for a booking agency to conspire with white promoters to restrain trade by not dealing with black concert promoters " (B.A. Memo.4), the Court stated on April 11, 1000 ( T l :90,91, emph. added): MR. K E S S L E R : . . . .What I wanted to point out, your Honor, is that this is a theory [trading the competition to benefit the lesser acts] i n search o f a factual allegation. T H E C O U R T : Is it. though? Don't we all know that you get a good piece o f the business and you are able to get some benefits for other people you represent? * * * I would think that the profits from the more profitable people somehow assist younger artists coming along. . . . 15) The Defendants' false allegation that Plaintiffs "manufactured a new economic theory for their conspiracy claims, conclusively alleging - with no supporting factual detail - that a 'quid pro quo' scheme existed . . . ." (B.A. Memo. 5) (emph. added), is rebutted by the testimony o f Bruce Kapp, President o f Touring for SFX/Clear Channel, who stated, in response to being asked whether promoters expected to receive some benefit from the agencies i n return for their willingness to accept the "baby" acts the agencies gave to them, " I think [promoters] would expect to be the 'promoter on record,'. . . i f that act happens. A n d i f i t was a real favor and they've lost a lot o f money, hopefully, they get another act or something; then the agency would take care o f them." (Kapp 173,226-27.) Indeed, this Court itself recognized the significance o f Kapp's testimony (T3: 68-69, 70-71, emph. added): MR. K E S S L E R : . . . .[Tjhere is no evidence o f such a quid pro quo.. . . THE COURT: There was a man named M r . Kapp. . . . He testifies that that kind o f an arrangement was made."' * "'Now, i f a booking agent gave a producer a break or a producer

-6-

gave a booking agent a break on minor acts, and in return, when they lost money, as M r . Kapp testifies to. then thev are rewarded in some wav by a subsequent contract, that seems to me would tend to keep a predominant promoter in that city. 16) The Defendants' repeated assertion that Plaintiffs produced no evidence on this point (B.A. Memo. 5), is rebutted by M r . Kessler's A D M I S S I O N (T3: 71) that Kapp' s testimony was evidence fi-om which to infer a conspiracy when he stated, "[o]ther than that single piece o f testimony [firom Bruce Kapp], there is no other incident from which to infer a conspiracy." 17) This Court has admitted that the good old boy network "exists all over the world. We all know o f the good old boy network." (T2;34.) 18) Regarding the Defendants' contention that it is the artists and their managers, not the agencies, who "make the ultimate decision with respect to selection" (T3:14), the Court repeatedly stated that it didn't matter (id. 14-15, 16, 37, 39, emph. added): . . . it doesn't seem to me that it makes much difference i f the agents perform the function o f screening out the plaintiffs or people o f color. It seems to me that i n screening out, that that's . . .as far as discrimination goes, very much like a discriminafion suit." * * * " I would think it would be grounds for a discrimination suit. That was my reaction as I read the papers. So I wasn't sure that this business o f ultimate decision on the artists and their managers was dispositive in any way."* * * "[A]s far as the discrimination claims go. it doesn't seem to me that it matters."* * * "Because i f they are one o f the participants and thev perform an act maybe it is ratified by someone else, but i f thev are the ones that screen out people, which is sort o f the way I read the allegations, from a discrimination standpoint, it doesn't matter."* * * "[Wjhether they screen or the ultimate approver doesn't really make much difference, it seems to me. i n the discrimination claim. . . .fT]he antitrust claims have got some problems. The race discrimination claim, on the other hand, is one that requires a lot o f detailed work by the Court to deal with "* * * "Wliat you hire an agent to do is make a proposal for your approval " * * * " I don't think it makes a h i l l o f beans difference Ln the discrimination.... 19) As to the affidavit o f Richard Johnson, this Court stated, " [ i ] t may be that [Richard Johnson's] affidavit has to be supported by evidence that is within the period i n question. It may be that it could be allowed as evidence o f background o f the conspiracy, i f you w i l l , that you're alleging. So it may be admissible evidence. But you still have to have evidence o f the acts within the statutory period you have set forth." (Id-: 40, emph. added.) 20) A t the Oct. 16 hearing, this Court stated to counsel for C A A , " I would hope i n this motion that you would address the plaintiffs' opposition because it seemed to me that your reply brief mainly reiterated your original position and there are a number o f points that

-7-

are made i n the plaintiffs' opposition that trouble me." (Id-: 53, emph. added.) 21) This Court rejected the Defendants' contention (with which i t ultimately agreed) that bids were critical to the Plaintiffs' failure to make a prima facie case (jd.: 59, 60 (emph. added): T H E COURT: What they are claiming in their b r i e f as I read it, is that they are being excluded from obtaining information about proposed concerts. Their bid process would only apply once thev have knowledge o f a pending concert. Thev are claiming that they are not told, just as M r . Campbell indicated with the Badu situation. It goes beyond that. Thev were told there was going to be no concerts by Ms. Badu. . . when i n fact the defendant booking agent. Ms. Lewis, knew there was a concert and told M r . Delsener. who had no experience i n that field, all about it. That's what they are alleging.* * * Bids don't mean anything. MR. KESSLER: There is no evidence that white promoters were given informafion. . .at the time they asked. The testimony was there wasn't that knowledge. It happened thereafter. They can't just infer this. They have to have some basis. T H E COURT: Have you established it? Does your evidence establish that in fact at the time there was no planned tour at the original time and that -- what about M r . Delsener not having the background in the field and h i m getting the business?^ The Coiut also recognized that the Plaintiffs had made nine bids when it inquired o f M r . Zweig, " [ w ] h y isn't the statement in your first point, bullet point there that the plaintiffs had nine bids for musical concerts contradicting your statement that they had made no bids." ( i d . : 105.) M r . Zweig admitted that "certain bids [were] submitted by M r . Jones and M r . Rowe." (Id.) 22) Regarding the Plaintiffs' contention that black and white promoters are treated differently concerning deposits, M r . Kessler argued, "[t]he fact that one particular promoter or two particular promoters in a particular concert got to negotiate a lower guarantee doesn't ~ " This Court interjected, "[tjhere is more than one or two. There are a lot o f them." (T3: 83, emph.added). 23) As to this issue is well, when Ms. Sperando stated, "1 just want to confirm once again this disparity and treatment w i t h regard to 50 percent, 10 percent" (id.: 169), this Court responded, "[t]hat you have done pretty well." (Id-, emph. added.) Subsequently, the following occurred between the Court and M r . Kessler on this issue (T4: 97, 99, 99-100,103-04, emph. added): T H E COURT: How do you respond to the contract that Ms. Sperando raised about the 10 percent - blacks only getting 10 percent whereas all those contracts show that the white

'The Court did not address this question in its opinion. -8-

people got better terms. MR. K E S S L E R : . . . Ms. Sperando showed you a few pairs o f contracts. T H E C O U R T : A lot o f contracts.* * * M r . Rowe has testified that he and the other plaintiffs have never been given contracts where you only have a 10 percent and here there are a number of contracts which apparently with white promoter [sic] i n which thev get 10 percentHow do I don't see how you can respond to that.

* * *

M R . K E S S L E R : . . . [T]his attaches the contracts for Lauryn H i l l ' s concert engagements in 1999, all o f whom are not white [and] are owned or controlled by African-Americans, and each o f these contracts requires the promoters to pay a deposit equal to 50 percent o f the contract guarantee. Again, the point here, your Honor, is that when you look at the population there is no way to draw an inference and - it was their burden on this point. T H E COURT: That was only ~ what about the ones that got less than 50 percent? 24) When Ms. Sperando showed a W M A letter to A m y Funk, a black promoter, demanding the full 50% deposit for a Queen Latifah date, Mr. Kessler objected that "[tjhat promoter has nothing to do with any" facts o f this case. (T3:164-65.) This Court responded, "[t]hey are showing an allegation they are following up on [sic] claim that white promoters are treated differently than black promoters i n the industry and this is certainly evidence that is consistent with the way they say that they were treated. That's perfectly appropriate." (Id., emph. added.) 25) On the first day o f argument, this Court stated, "[cjertainly the points being made by Ms. Sperando were not dealt w i t h by the defendants." (id.: 16869) (emph. added). 26) This Court recognized that the terms o f the Janet Jackson contract C A A gave to Magicworks and Rowe were "considerably different." (Id.: 129, 179-80, T4: 8, emph. added.): T H E C O U R T : Putting up one million five i n four days, it might be pretty hard for most people when. Another, 5 in 40 days and then another 2 million a week before the first sale is a little different than 507 [sic] percent prior to the first on sale date. It requires a greater amount o f time between the time you can recoup on any tickets sold.* * *1 agree w i t h you it looks to me as i f the demand is higher than Magicworks draft deal.* * * I don't disagree with you that it looks to me as i f that contract that Magicworks has is a better contract from Magicworks' standpoint than what was being suggested to Mr. Rowe on March 4. But what I don't agree with you on is some o f the specifics 1 agree w i t h you that parts o f it are more favorable. As I see it here, there may be an explanation, but I agree it looks more favorable. . . . I don't disagree with vou that it looks to me as i f the contract, the proposal [Mr. Rowe] was more onerous than the contract term that Magicworks was being offered or drafted. 27) This Court stated that the Zedeck letters to only the dominant white promoters which gave notice o f an upcoming tour o f a white artist "may be material infonuation with respect to the antitrust

-9-

argument. . . ." ( T 4 : l 1.) 28) Regarding the Leff letter and its antitrust conspiracy implications, this Court acknowledged that Leff was saying that Beaver never tried to move into Memphis and then added, "he goes a little bit farther. I think he is saving because when M r . Kellev was around he a was dominant promoter evidently and Mid-South was a dominant promoter and we didn't promote i n Memphis." * * * "The talent agencies involved is an issue." (Id.: 53, emph. added). 29) M r . Campbell showed the Court how there was collusion between "the top talent agencies" and Beaver regarding the antitrust conspiracy and pointed to L e f f s overt acts in his letter o f A p r i l 20 and those o f Shelly Schultz o f W M A is his A p r i l 17 letter to Susan Green (then employed by Beaver) stating that W M A was cancelling the concert o f James Taylor, a prominent white artist, at M u d Island and was going to book it at the Mid-South Coliseum. To all o f which this Court responded, "[n]ow you're giving me something that I c a n - " (id.: 53-54; emph. added.) 30) This Court stated to Plaintiffs' counsel, "[yjou're showing a connection between M r . Fox and the top talent agencies because M r . Fox is cc'd on the letter to Ms. Green canceling the concert. They are cc'd." (Id.: 55)' When M r . Kessler stated that Fox was not a talent agent, this Court responded: [h]e is a promoter. He is cc'd on William Morris', who is a talent agent, letter o f that date. It shows communication with a top talent agent, which M r . Fox denied that he had been i n communication with the top talent agent, but it's clear here he has been.'"^ * * " M r . Fox o f Beaver is in touch with W i l l i a m Morris. W i l l i a m Morris cancels a concert at Mid-South [sic]. And it's all i n the same time frame with the letter from M r . Leff to the M u d Island, whatever it is. or the city agency. It does look as i f the talent agents had given him an encouragement to write the letter."* * * " [ Y ] o u have shown me the documents that show a cormection. (Id.: 58-59, emph. added.) When M r . Kessler stated that that was the iSrst time Defendants had heard "that there was a separate antitrust claim about M u d Island," this Court stated, " I don't think it's separate. 1 think it's indicative [of] what they are saying." (Id.: 81, emph. added.) 31) Thereafter, when M r . Kessler stated that Mayor Herenton had decided, prior to Kelly's death, that there would be no more exclusive contracts for M u d Island, this Court stated, "[y]ou do have a situation where apparently, according to the plaintiffs, he and I guess counsel had three days or so prior to this supposed changed

^The Court acknowledged it meant Mr. Leff -10-

o f heart, had not -- had indicated that the exclusive contract would go on." (Id.: 82-83; emph. added). M r . Kessler contended that the only support for that "is the claim o f the p l a i n t i f f . . . . Jones testified that he had had that conversation w i t h the mayor and had been given that assurance. There is nothing else to back that u p . . . ." (Id.: 83.) This Court responded, "[tJhat raises an issue." (Id., emph. added.) 32) Mr. Kessler admitted that it "raise[d] a factual dispute," albeit not a material one, and argued that the decision to open up M u d Island was not anticompetitive. This Court responded, "[w]ait a minute. You have beyond that. That part itself no. But then what about the interaction between W i l l i a m Morris and Beaver and Ms. Green i n moving i n . " (Id-; emph. added.) 33) WTien Mr. Kessler stated that " [ w ] e agree that eliminating the exclusive can't be anticompetitive," this Court stated, " I don't know that I agree with diat. It all depends on the total picture." (Id.: 84, emph. added.) 34) Mr. Kessler then argued, "[a]ll they have is one document about James Taylor. . . . it wouldn't show an antitrust conspiracy even in Memphis." (Id.: 85.) This Court responded (id., emph. added): Not antitrust. Y o u ' r e going to deal with the discrimination claim. Here is James Taylor. He is booked into M u d Island. Because of the death o f M r . Kelly. M r . Jones is the surviving partner. He is a black promoter. Lo and behold, what do they do? They hire Ms. Green and take the concert away from promoter Jones and give it to Ms. Green. 35) This Court also rejected the economic implausibility argument made by Darrell Williams, the Defendants' economist, concerning the antitmst conspiracy (id.: 64): I am not so sure that economic analysis argument is a thorough analysis o f the benefits that can be the economic motivation. Because over time it seems to me you bring along these small acts and they become the big acts. You can't look at it i n a prism o f a single year. Y o u have got to look at it in developing talent, and that's what W i l l i a m Morris is engaged i n , i f I understand it. They want to develop talent and they want to have a star act. In order to get a star act, you have to have exposure. I am not too impressed with that argument because it seems to me it has a time limitation on i t . . . . 36) In response to M r . Kessler's argument that there was no evidence that the booking agencies had established dominant promoters, this Court stated, " I think i f they could show that the booking agents had in fact estabhshed it by testimony, then proceeded to utilize it in its established form, there would be a claim, wouldn't you agree?" (Id-: 93, emph. added). In fact, Richard Johnson did attest that the

-11-

agencies established promoter dominance (Johnson A f f . f f 3 , 4 ) and Defendants' expert, Mario Gonzalez, did testify that the agencies utilized it i n its established form. (Gonzalez 143,147.) 37) M r . Kessler tried to argue that i f there was a conspiracy to divide up the market, the Plaintiffs would not be hurt because there would be fewer promoters to compete within each market. (T4: 94-95.) The Court noted, "[t]hey have the exclusives. They have the relationships. . . . What about their position and they showed me documents that showed promoters saying we always respected your area o f dominance." (T4: 95, emph. added). 38) Towards the end o f the two and a half day argument, this Court stated, "1 believe, frankly, that there is racism, and probably racism in this industry. . . . " (T5: 231.) 39) Far from concluding that the Plaintiffs' claims or evidence was frivolous, this Court stated, "[t]hat is the heart o f the matter, whether there is enough there to infer discrimination under McDonaldDouglas . . . ." ( I d ) 40) When the Court asked what was the evidence o f Beaver's contention that "multiple African-Americans are more successful in this business than . . . Beaver," M r . Cobb responded, "[t]he evidence o f Alan Haymon's testimony." (Id-: 263.) This Court then noted, "[j]ust him, that is the only one I have heard." (Id-, emph. added.)' 41) When Mr. Cobb argued that promoters do not decide who gets a contract, this Court asked h i m , "[w]hat about knowledge o f the fact that black promoters . . .never seem to get selected in the industry?" (Id-: 265, emph. added.) 42) When M r . Cobb noted that B i l l Washington had promoted several national tours, this Court asked, "[c]opromotion?" (id.: 270, emph. added), indicating that the Plaintiffs' argument that black promoters merely co-promoted the white acts but did not contract therefor because they were merely co-promoters had made sense to the Court and was not frivolous. 43) When M r . Cobb argued that the James Taylor concert in Memphis is not an overt act and was not pled, this Court responded, "[b]ut it is evidence before me." (id.: 294, emph. added.) 44) The Court agreed that Alex Cooley's testimony that there is a good old boy network, Wavra's testimony that there is a white promoter fraternity, and Delsener's testimony that African-Americans are not given equal opportunity are admissions ( T l : 66.) 45) After

'The Court never found that any black promoter was more successful than Beaver. -12-

two and half days o f argument, instead of rulmg from the bench, which this Court could have done had the claims been frivolous, vexatious, or litigated in bad faith, this Court stated, "[d]ecision is reserved, obviously." (T5:295, emph. added.) Thus, the Court's numerous statements regarding the merits o f the Plaintiffs' claims refute the Defendants' allegations that they were frivolous or made i n bad faith. See A F S C M E v.. Nassau. 96 F. 3d 644, 653 n. 2 (2d Cir. 1996), cert, denied. 520 U.S. 1104, 117 S. Ct. 1107 (1997) (court's conclusion, after bench trial, that claim was frivolous was i n "some tension w i t h " its earlier denials o f defendants' motions to dismiss and for judgment as a matter o f law at close o f plaintiffs case at trial). Moreover, this Court erroneously disregarded the affidavit o f Richard Johnson because he was last a W M A agent i n 1986 (7,32, 39,41 n. 60,83,113 n. 149,129,171-72) and numerous statements o f Rowe on the grounds that is not an expert (27,83 n. 121,105) and has no personal knowledge o f that to which he was attesting (passim). As noted i n Danzer v. Norden Systems. Inc.. 151 F.3d 50, 57 (2d Cir. 1998)(footnotes omitted)(emph. added): There is nothing in [Rule 56(c)] to suggest that nonmovants' affidavits alone cannot-as a matter o f lawsuffice to defend against amotion for summary judgment.* * * In discrimination cases, the only direct evidence available very often centers on what the defendant allegedly said or did. [Citation omitted.] Since the defendant w i l l rarely admit to having said or done what is alleged, and since third-party witnesses are by no means always available, the issue frequently becomes one o f assessing the credibility o f the parties. A t summary judgment. . . that issue is necessarily resolved in favor o f the nonmovant. To hold . . . that the nonmovant's allegations o f fact are (because 'self serving') insufficient to fend off summary judgment would be to thrust the courts-at an inappropriate stage-into an adjudication o f the merits W e therefore reject defendants' invitafion to create this new rule. Furthermore, a witness's personal knowledge doesn't have to rise to the level o f certainty to be admissible. U . S. v. Reitano. 862 F.2d 982, 987 (2d Cir. 1988); U.S. v. Evans. 484 F.2d 1178, 1181 (2d Cir. 1973); S.E.C. v. Singer. 786 F, Supp. 1158, 1167 (S.D.N.Y. 1992). When a witness had an opportunity to observe the facts upon which he bases his testimony, insofar "as those tacts include his own behavior and the obser\'able interactions between himself and others, the testimony is entirely admissible." Id. It is then thejury's role to detennine whether to believe the testimony. I d . Testimony

-13-

may be admissible even i f the witness only has a broad general recollection o f the subject matter. I d . ; U . S. v. Peyro. 786 F.2d 826, 830 (8th Cir. 1986). Conclusions based on personal observations over time may constitute personal knowledge despite the witness's inability to recall specific incidents upon which he based his conclusions. Singer, 1158 F. Supp. at 1167. Such conclusions are not conclusory and argumentative statements, or speculation, and are admissible. Joy M f g . Co. v. Sola Basic Industries. Inc.. 697 F.2d 104, 110 (3d Cir. 1982). When a witness has extensive knowledge o f a subject he is also allowed to proffer an opinion, which is rationally based on his knowledge, as a personal observer, o f the specific subject matter. Id.; Singer. 786 F. Supp. at 1167-68. Thus, Johnson's affidavit was admissible because he had been a W M A agent for four years and because it was based on "his continuing familiarity with the concert booking promotion business" (Johnson A f f f 3 ) , and most, i f not all, o f Rowe's statements were admissible because Rowe has 30 years o f experience in and knowledge o f the concert promotion industry. (Rowe A f f ^3.) Whether their testimony was to be believed was a j u r y question. Singer, 786 F. Supp. at 1167-68; Holz v. Rockefeller & Co.. Inc.. 258 F.3d 62, 69 (2d Cir. 2001); Camerlin v. New York Cent. R. Co.. 199 F.2d 698, 704 (1st Cir. 1952) (use o f discrimination plaintiffs own testimony sufficient to raise inference o f discrimination and its credibility was a question to be determined at trial). But even assuming Johnson's affidavit and portions o f Plaintiffs' Rule 56.1 statements and supporting affidavits, were properly disregarded, there is a plethora o f conipetent evidence showing that Plaintiffs' discrimination claims were not vexatious, frivolous, or made in bad faith::'"/" Beaver: 1) This Court made short shrift o f the contention that Plaintiffs should not have sued Jam and Beaver because o f Haymon's opinion when it succinctly stated, "[h]e is no expert" (T4: 80) and dismissed the dispute concerning whether Haymon was one o f the leading national tour promoters,

'^Regarding the alleged deficiencies in the Rule 56.1 statements and supporting affidavits, the Plaintiffs and their attorneys have already been punished by the Court's disregarding those statements it deemed insufficient. ' 'Plaintiffs have space to explain only a fraction of the evidence which proves that the Plaintiffs' claims were not vexatious, fiivolous, or made in bad faith. (Sperando ML ^13.) -14-

saying,".. .that isn't important any way." (T4: 76.) Haymon was one o f the original signatories to this htigation before the suit was filed and when the promoters were included as Defendants on the retainer agreement (Ex.11), but withdrew when he began negotiating to sell his company to SFX. (Pis.' C A A , Rowe ^54.) Haymon is not a lawyer and has no legal training. (Haymon 272-73.) See n. 5 supra; 2) expert testimony was not necessary' to prove the Plaintiffs' claims against Beaver: a) three weeks after (white) Kelley's death. Beaver opened a Memphis office, b) L e f f s A p r i l 20,1998 letter ("we have been asked by the top talent agencies to establish an office i n Memphis") seeking to prevent Fred Jones from obtaining an exclusive agreement to promote concerts at M u d Island i n Memphis, c) A p r i l 17, 1998 letter from Schultz o f W M A to Susan Green with regard to moving James Taylor concert from M u d Island (Jones) to Mid-South Coliseum (Beaver) and d) December 3, 2002 admission o f Beaver's counsel that, " [ o ] n its face, the letter Barry Leff sent to Wayne Boyer could be. through creative argument, considered as evidence o f conspiratorial or discriminatory conduct." (Ex. 10, emph. added), refiite any claim o f finvolousness and bad faith as to Beaver; 3) although initially Herenton testified that he "to [his] knowledge had never seen [the Leff letter] before" (Herenton 40), he then T W I C E testified " I don 't recall" when asked whether he had known about Beaver's inquiry on A p r i l 21 when he decided not to approve an exclusive at M u d Island (id. 77-78) (cf. (99,100)); 4) the undisputed evidence is that after five years o f twice agreeing to an exclusive at Mud Island, Herenton decided that it was in the best interest o f Memphis not to have an exclusive there on April 2 1 . 1998. one day after the date o f L e f f s letter (id. 64, 83-84), for two reasons which he had known about when he approved Island Event's exclusivity agreement i n 1995 (id. 89-90-94); 5) Fox "[could not] remember" (not that he did not know (cf. (100)) whether he knew that Jones was black when Leff wrote the letter (Fox 39); 6) it would have been in Beaver's economic best interest not to have Mud Island subject to an exclusive contract (101) and to open a Memphis office (102) while Kelley was alive, but Beaver only moved into Memphis after Kelley's death when a black promoter stood to inherit the exclusive; 7) just because it was i n Beaver's economic best interest doesn't mean it was not racially motivated; 8) L . B A H / E Y

-15-

testified (Bailey 80-82) that he obtained the Kenny G dates not from C A A but only at the insistence o f Kenny G and Dennis Turner (cf. 103 n. 138); 9) thus, that Fox has never involved any black promoter as a co-promoter when a white artist was the featured act is unrebutted; 10) the Court 's conclusion that Beaver's moving into Memphis after Kelley's death "could be consistent with a racially motivated conspiracy to interfere with a contractual relationship" (102, emph. added), estabhshes a jury question (Chambers v. T R M Copv Ctrs. Corp.. 43 F.3d 29, 38 (2d Cir. 1994)("[i]t is not the province o f the summary judgment court itself to decide what inferences should be drawn"); 11) Beaver's "bids" (62, 103 n. 139) were not bids but "Expense Sheets" as they state, submitted A F T E R T H E P R O M O T E R H A S T H E D A T E which is when he gives an estimate o f expenses. They contained no offers. The Plaintiffs explained this at oral argument (the expense sheets were attached to Beaver's Reply to which the Plaintiffs could not respond), and that they had propounded a document request to Beaver in which they had asked for all solicitation materials to which Beaver objected, and when the Court ordered them to respond. Beaver still produced no bids. (T5: 281, 29293.) The Court accepted W M A ' s counsel's assertion at oral argument that Delsener/Slater "controlled" the Supper Club. (118 n. 161.) Thus, Plaintiffs' counsels' statement at oral argument that Beaver's "bids" were Expense Sheets created a fact issue as to whether Beaver had ever submitted any bids. Moreover, Beaver's accountant, Steve Grishman, is not a promoter or agent and, therefore, is not competent to attest to what is a b i d (T5: 292); 12) Plaintiffs "[cite[d] no evidence that Jam or Beaver did not submit bids for concerts" (62) because one cannot prove a negative, but Rowe did attest that he had not found any bids from them. (Pis.' Beaver, Rowe Decl. ^26.) Jam: 1) Since a) Rowe submitted a bid for the 1998 postponed (not cancelled) (cf.(68)) (see press

release, E x . 12) Chicago Maxwell date(s), b) there is no record evidence that Jam submitted any bid for those dates in 1998 or 1999 (or at any time) but got them nonetheless (one can't compete with a bid that isn't made), and c) W M A did not advise Rowe that Maxwell was touring i n 1998 or 1999 (Pis.' Jam, Rowe ^[21), a reasonable inference is that Jam and W M A conspired to prevent Rowe from getting

-16-

the Chicago dates; 2) Jam is the dominant promoter in Chicago (Kapp 237) (cf. (81-82)); 3) A l Kennedy's Dec. 4, 2000, affidavit is not competent because Rosie O'Donnell is not a contemporary music artist (3, 49 n. 71) and no date is given to show that the Average White Band date was during the period covered by this action; 4) the unrebutted evidence that Jam has co-promoted white acts with white promoters (Mickelson 108-110) and numerous black acts with black promoters (Granat 36-43; Mickelson 110), but neither Granat (Granat 67-79) nor Mickelson (Mickelson 109. 111-13) can name a single white act Jam co-promoted with a black promoter is evidence o f discrimination; 5) Jam's allegation that "[b]efore the commencement o f this litigation, Jam did not have any knowledge o f the conspiracy alleged by plaintiffs" (86) cannot of itself refute its knowledge because i f it could, a plaintiff could never prove a 1986 violation; 6) when Haymon contracted for five Lauryn H i l l ( W M A ) dates, he had to pay 50% deposit. (Pis.'Jam, Ex. 14.) This Court noted, "[h]e had a big guarantee." (T5:224.) In that same year, for two Lauryn H i l l concerts. Jam paid a 10% deposit. (Id-, Ex. 10.) Although the Court initially thought that the seating arenas used by Haymon and Jam were different, they were not. (T5: 224-25.) As M r . Campbell noted, it was a "[pjerfect apples-to-apples comparison" (id: 225); 7) the fact that both Haymon and Jam were offered the same deposit (85) is not dispositive o f whether there is an inference o f a conspiracy with W M A to discriminate because a) there are contracts where Jam was offered and paid a 10% deposit (Pis.' Jam, Ex. 12), but none as to Haymon or any other black promoter, b) Jam has produced no evidence that, like it, Hayiuon was allowed to negofiate for a 10% deposit and c) Jam's alleged ability to negotiate begs the question as to why it can do so but black promoters cannot. WMA: 1) MJP was not the "tour promoter" for Maxwell, i.e., one who "has exclusive rights to

the artist's current performances and may negotiate for specific concerts with local promoters instead o f the artists or agent." (13, emph. added.) W M A inserted MJP i n the Maxwell tour at 50%. instead o f the usual 100% to circumvent the Plaintiffs' charges o f discrimination. Thus, MJP was forced to use the white promoters W M A had selected. (Ex. 13.) (Cf. C A A sold Magicworks 100% o f the Janet

-17-

Jackson tour, and thus, it. not C A A . had the right to decide on local promoters. (Light Dec. I ^^49,50); 2) Rowe was never told about the 1998 or 1999 Maxwell tour even though he had made offers (to which W M A never responded) for seven cities for the postponed, not cancelled, 1998 tour (Pis.' W M A , Rowe f 21); 3) Rowe's offers in total were $85,000 higher than those of the promoters W M A selected (id-, Ex. 20); 4) W M A ' s "data" on the bids it received, accepted and rejected (63), violated the best evidence rule (Fed. R. Evid. 1004) because it did not produce the bids or documents themselves (and not even the computer printout of the data with the exception of Badu data) and thus was inadmissible; 5) Boseman called Lewis to inquire about Badu dates and Lewis told him she was not going out (Pis.' WMA, Boseman t 2 2 ) ; 6) Lewis never called Boseman to tell him Badu was going to tour despite his expressed interest (Boseman 725); 7) Lewis's testimony that she told Boseman that Badu was playing only at small venues (117) is controverted by Boseman's testimony that Lewis told her only that Badu was not going to tour and, therefore, he did not propose dates or other venues (id. 722-23); 8) the statement to Boseman from Delsener and Slater that Lewis had told them, " i f they do business with Sun Song, that she wouldn't do any business with them any fiirther" (jd. 737-38), although hearsay (117 n. 158), is admissible to show Boseman's motive for not calling Lewis and requesting a specific venue. (Fed. R. Evid. 803(3); U.S. v. Ostrander. 999 F.2d 27, 32 (2d Cir. 1993). He knew that that would have been futile and thus was exempt from having to bid under Petrosino: 9) that Badu ultimately played in New York venues allegedly exclusively booked by the building (118) is irrelevant to the fact that Lewis lied to Boseman (PAS Communications) (concealing information about bid opportunities is discrimination); 10) W M A submitted no competent evidence i.e., the contracts (Fed. R. Evid. 1004) showing that Lionel Bea, B i l l Washington, Darryl Brooks, Anthony Williams, Earnest Brooks, MJE, and Mary Flowers (123) promoted (not co-promoted) Lauryn H i l l , i.e., S I G N E D T H E C O N T R A C T , although it did produce the contract that Haymon/SFX signed, thus indicating that black promoters did not promote H i l l ; 11) that ablack promoter. Flowers, co-promoted the Hill date Boseman was promised (124) is iiTelevant as to whether race was a factor regarding Lewis's lie to Boseman (PAS

-18-

Communications): 12) Schultz's testimony (126) that Taylor's management decided to use Beaver (Schultz A f f . f 8 ) , is infirm because it is inadmissible hearsay. management. W M A did not depose Taylor's

Thus, W M A has presented no evidence to rebut Plaintiffs' prima facie case o f

discrimination regarding the Taylor concert and there was no need for Plaintiffs to show that W M A ' s reasons for its actions were pretextual; 13) W M A ' s "evidence" is pretextual because that Beaver was going to promote Taylor i n Arkansas four days before the Memphis concert had nothing to do with who could or should promote Taylor in Memphis. It didn't matter when Kelley was promised the Memphis date. Schultz's statement that they did not have a promoter at M u d Island is untrue because W M A could have used Jones; 14) whether Schultz is telling the truth that he didn't know o f Jones when he wrote to Green (126), given the timing o f these events, is for the jury. This is especially true because Schultz falsely attested that at the time of Kelley's death, he and Kelley had only an oral understanding that Kelley was to promote Taylor at M u d Island (Schultz A f f f 6 ) , when i n fact in his Mar. 3, 1998 letter to Kelley he states that "the dates [June 23-24] are okay, we w i l l soon r e c o n f i r m the deal" ( E x . 14); 15) Defendants' "evidence o f the promotion o f white artists represented by W M A by black promoters," i.e., Darryl Brooks (Eminem); Bill Washington (New Kids On The Block, Average White Band, Santana), Larry Bailey (Average White Band, WAR); Mary Flowers ( T o n y Bennett); and Rowe (Average White Band) (127-28), is not competent because a) Fed R. Evid. 1004 requires that the contracts be produced, which W M A did not do, b) Washington, Brooks, Flowers and Bailey were copromoters, not promoters who actually signed the contract, c) W M A cites no dates for these alleged contracts, d) Santana and War are not white acts, e) even assuming that these black promoters promoted each o f these artists during the relevant time period at issue, and that Santana and War are white artists, these H A N D F U L O F dates, out o f the thousands o f contracts by white artists during the relevant period, are sufficient evidence to allow a jury to determine whether W M A discriminates against black promoters and die Plaintiffs i n particular; 16) Grosslight's declaration showing that WMA "produced to Plaintiffs its electronic database o f concert bids received" (128) is not competent

-19-

evidence because it is not (he best evidence o f those "bids," i.e., the bids themselves which W M A presumably has, and does not allow the Court to determine a) the accuracy o f the information culled from W M A ' s elecfronic database, b) when the bids were received and, thus, whether they were truly competitive or received after the date had been sold to a dominant white promoter, or c) how many dates W M A sold and whether there was a bid for each date sold; 17) the Court finds that the Plaintiffs failed to cite any evidence to support their claim that W M A "withhold[s] information necessary for black promoters to submit compering bids " ( 1 2 9 . ) However, both Rowe (Pis.' W M A , Rowe f 39) and Boseman (id., Boseman ^[22) testified that Lewis falsely told them that Badu wasn't going out even though she was; 18) artists' and their managers' testimony that all bids are referred to them (129) is incompetent because they can't know whether W M A withholds any bids; 19) Haymon testified that W M A has not passed on his bids (Haymon 191-93); 20) Schultz's explanation as to why he sent a notice letter to 39 white promoters but none to a black promoter (i.e., discussions w i t h management and 39 were promoters who worked with Culture Club i n the past (130)), is infirm and thus requires no response from the Plaintiffs because "discussions with management" are inadmissible hearsay;'^ 21) the reason is pretextual a) because notifying past promoters o f upcoming concerts did not occur when it involved black artists nurtured to success by black promoters (Pis.'WMA, Rowef29), and b) i f the initial decision to use a promoter for Culture Club was based on race as the Plaintiffs allege, then notifying those same promoters for an upcoming tour in no way demonstrates a race-neutral reason for ^ continuing to notify them and serves only to perpetuate the discrimination and resulting injustice; 22) Plaintiffs need not show that all "similarly situated non-minority members were freated

differently"( 130) but only that all blacks were treated differently from similarly situated non-minority promoters. CGrant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.. 635 F.2d 1007, 1017 (2d Cir. 1980)("failure to solicit qualified blacks.. .constitutes.. .discrimination.. .since whites were being solicited at the same time").

'^Although "Plaintiffs chose not to depose management of Culture Club" (130 n. 171), so too did WMA. Moreover, the Plaintiffs' persuading artists and managers to testify in this matter at all, much less in a manner that would bite the hand that feeds them, was very difficult. (Sperando Aff. ^3.) -20-

(See letters from W M A to only white promoters) (Pis.' W M A , Ex. 117); 23) "the Promoter Defendants are also offered contracts by W M A calling for a 50% deposif (131) and "Plaintiffs have not shown that their selection o f contracts is representative" (131 n. 172): Plaintiffs' evidence is sufficient to show an alarming number o f Promoter Defendants are offered contract terms that all black promoters don't get, the only exception i n this record being two 25% deposits by Bailey for Kenny G (141 n. 182) (but see special relationship with Kenny G), thus proving that the overwhelming majority o f the time blacks were disfavored, a fact that cannot be explained by anything other than race since black promoters (Haymon) who have the alleged requisite qualifications (e.g., financial stability), are treated the same way as the Plaintiffs. The only reason "race-neutral" Defendants offer, i.e., that the white promoters are able to negotiate better terais (132), begs the question as to why white promoters can do it but blacks, including Haymon, cannot;'^ 24) the long-standing relationships between W M A and some white promoters "just as successfully exclude other white promoters" and, therefore, no racial animus has been shown (132): this is not the test. I f it were, Plaintiffs would have to show that no black promoters are a part of the "good ole boy network," and all white promoters are a part o f it. Such a burden would be akin to claiming that because some whites may be denied the right to live i n a white apartment complex that doesn't allow any blacks, racism could not be the motive for keeping all blacks out C A A : 1) When Rowe called C A A to ask who was going out, he was never told about any white artists. (Pis.' C A A , Rowe 1155) (PAS Communications): 2) T o m Ross (Ross 20,21) and Dennis Ashley (Ashley 29, 43, 5 1 , 58, 64) confirmed that C A A agents routinely call the promoters to notify them about concerts; 3) Light admits that Rowe inquired about Eric Clapton before this lawsuit but "[he doesn't] remember" whether he or anyone at C A A ever told Rowe that Clapton was going on tour (Light 467) (PAS Communications): 4) Nederlander got a 90/10 artist split for 1997 Kenny G date i n California

''The Haymon/Jam Stevie Wonder deposit of 25% each (86 n. 124) amounted to a total deposit of 50%. -21-

(85 n. 113); 5) at no time was Rowe told that the guarantees on the Kenny G tour had been lowered to $ 150,000-$ 175,000, but Jam (and the other dominant white promoters) knew about and benefitted fi-om the lower guarantee which Rowe learned about by accident (Pis.' C A A , Rowe ^223); 6) even though Rowe acknowledged that he had the "opportimity" to bid on Kenny G/Braxton (78,139), the terms he was given were significantly higher than those given to the dominant white promoters: Piranian told Rowe i n Oct or Nov. 1996 that the minimum guarantee was $225,000 to $275,000 (Pis.' C A A , Rowe t215, Rowe 1382, 1384), but the Evening Star Nov 26. 1996, Contemporary Nov 12. 1996 and Jam Nov. 25.1996, contracts show that they paid $135.000. $150.000. and $150.000. respectively (Armand Decl., Ex. A ) ( c f . (139.141)). thus "support[ing] a prima facie case o f discrimination under McDonnell Douglas" (139. emph. added); 7) that C A A hired its first black agent within six months o f this lawsuit's having been filed (13 5 n. 177), and other instances o f C A A ' s racist hiring policy and work environment (e.g., noose incident) (Pis.' C A A 21-22), create an issue o f fact as to whether C A A "has a policy o f equality and equal opportunity" (Lovett 99-100), and are relevant to C A A ' s credibihty when it denies civil rights violations as to these Plaintiffs; 8) it is not necessary "to show that C A A ' s business reason, instructions from its principal, for demanding guarantees between $225,000 and $275,000 was a pretext" (139) because a) C A A did not present a nonpretextual business reason because it has not shown that it was instructed by Turner Management to offer a higher price to Rowe than it was offering to Evening Star, Contemporary, and Jam, and b) despite Rowe's having expressly told Piranian o f the B P A ' s desire to promote Kenny G/Braxton dates, no one fi-om C A A advised diem o f the reduction i n price (Pis.' C A A , Rowe1 [223); 9) Jackson's and Davies' statements that "it was important to involve black promoters i n the tour and decided to require black representation on the tour" (143) are inadmissible hearsay (cf. 143 n. 189)) because the statements are being offered for the truth o f the matter asserted because the Court finds, "[biased on the parameters set by Ms. Jackson and M r . Davies. M r . Light informed interested promoters . . . that Janet Jackson was seeking a guarantee o f $300.000 per show" (143-44, emph.); 10) Davies' instnaction to C A A to "inform the interested promoters that

-22-

Ms. Jackson was looking for forty dates . . . " (146) is hearsay because it is offered not merely for the fact that an instruction was made, but also for its truth, i.e.. Light declares that he " i n accordance with Mr. Davies instructions, informed [Rowe] of the deal terms that Ms. Jackson was seeking" (146, emph. added); that Light states that he makes his declaration on personal knowledge does not transform what someone else told him into non-hearsay (cf. (146 n. 197)); since Light's alleged business reason was hearsay. Plaintiffs need not provide evidence that it was a mere pretext (cf. (147)); 11) the terms o f Magicworks' final contract were different fi-om those offered to Rowe (T3:180); 12) regarding the financial terms required o f promoters, this Court stated, "I can see i f the terms are different, o f course it would be discriminatory " (T2: 61, emph. added); 13) Ross testified that Rowe had made the best

offer w i t h a guarantee o f $300,000 per show (Ross 260); 14) Carole Kinzel's handwritten note wherein she stated "do not divulge [Janet Jackson's] guarantee to Black Promoters (Ex. 15); 15) C A A submits no contracts for Bailey (Harry Connick, Jr., Styx, Three Dog Night, Kenny G) or for Washington (Santana) (157) and thus, this evidence is not competent because it is not the best evidence o f what occurred and does not show whether these contracts were signed a) during the period at issue, and b) by the black promoters or whether the black promoters, all two o f them, were merely co-promoters; 16) even were C A A ' s evidence on this issue competent, that the best C A A can do is come up w i t h two black promoters who have promoted six white artists ( i f one includes Santana), out o f the thousands o f dates for white artists for which C A A was responsible since 1995, proves that the only way C A A was going to offer white artists to black promoters was i f they sued it (156); 17) memo from Kinzel to Ross explaining how Magicworks had cost Janet Jackson $672,500 to $ 1.37 m i l l i o n or more (Pis.' C A A , Rowe, Ex. 41), a fact which was never told to Janet Jackson (Light 653) (cf.l58)); 18) "[p]roviding advance notice to all [1000] promoters o f concerts" would be neither formidable nor costly by means o f the internet where millions can be e-mailed with the touch o f a button (cf. (id.)); 19) C A A ' s giving advance notice to only some white promoters and no black promoters constitutes discrimination. Grant. 635 F.2d at 1017; 20) widespread notice may or may not create a heavy burden

-23-

on artists' management because the vast majority o f dates may be so costly that the vast majority o f promoters would not bid: jxiry issue (cf. (159)); 21) keen competition among promoters would enure to the benefit of the artist to whom C A A owes its first duty (Haymon 475), not the artist's management (cf.(159).) Renaissance: 1) Dream was a support act in 2001 (i.e., when it was SFX/Haymon) (Haymon 181 -92, 263); 2) no black promoter, including Haymon, ever promoted any white artist Renaissance represented or has ever been solicited by Renaissance although it has routinely soUcited white promoters (Pis.' Ren., Comp. Ex. 16, Rowe ^ 1 1 , 2 2 , Haymon 314-25), thereby estabhshing a "promotion history o f systemic discrimination" (166); 3) on a summary judgment motion. Renaissance had the burden to produce its contracts o f black promoters for white acts and its bids firom promoters to whom it sold dates, but i t has not produced (cf. 167); 4) just because Renaissance did not notify aU white

promoters o f its white artists' upcoming dates (166) does not mean that its refusal to notify miy black promoter o f those dates is not discriminatory; 5) Renaissance did not establish that race was not a factor i n Zedeck's decision to notify O N L Y W H I T E promoters; 6) however Zedeck found the white promoters he soHcited, he did not submit any evidence showing that he ever solicited any black promoter (including Jones (Pis' Ren., Jones 1|3)) even though he admittedly knew that Jones was a promoter o f concerts as o f Dec. 1998, because Jones promoted Renaissance (minor black) artist Cox in D e c , 1998 (Zedeck I f 14 n. 1), and Jones had expressed to him an interest i n N'Sync (Pis.' Ren., Ex. 38); 7) Zedeck's explanation that the fiinction o f his faxes on behalf o f white artists to only white promoters as an attempt to interest promoters in his artists (168-69), does not rebut Plaintiffs' allegation that this was discriminatory and thus Plaintiffs did not have to show that it was a pretext (i.e., why not attempt to interest black promoters i n The Backstreet Boys i f race was not an issue?); 8) although the "national tour agreements [for Spears, N'Sync and The Backstreet Boys] already were in place" (Zedeck 1, ^15(c)), this would not have prevented Zedeck from trying to get the Plaintiffs dates as local promoters as is commonly done i n the industry (Grosslight ordered Haymon to use Beaver as a

-24-

promoter for Whitney Houston (Haymon 328); 9) although the Court finds (165) that the Plaintiffs made no offers to Renaissance despite a) their expressed offers o f interest ( i d ) a n d b) this Court's position that "[b]ids don't mean anything" (T3:59), making such offers was unnecessary for white promoters whom Renaissance solicited for bids (Pis.' Ren., Comp. Ex. 16); 10) that a "number o f promoters used by Renaissance are not among Plaintiffs' alleged dominant promoters" (168) is meaningless to the discrimination claims; what is relevant is that they are A L L W H I T E ; 11) that Plaintiffs did not bid for the contracts where white promoters got 10% or no deposits does not mitigate the discrimination because Renaissance has failed to prove on summary judgment that i t has ever agreed to such deposit amounts for any black promoter or that had a black promoter bid for these dates, they would have received these more favorable terms; 12) that "[tjhese more favorable terms would impact competing white promoters as much as any black promoter'' (170-71) is irrelevant because the test is not whether all white promoters get favorable terms but whether all black promoters do not; 13) the Court never considered whether race was one o f the reasons why white promoters received better terms or allegedly had a "better bargaining position" (171) (there are black promoters who have "recognized financial strength" (id.) (e.g., Haymon, Washington)); 14) Zedeck's statement that managers accepted better terms "based on many years o f relationship with the promoter, or the promoter's history, reputation or apparent financial wherewithal" (id.) is submitted for its truth and thus is inadmissible hearsay; and 15) Zedeck sent Boseman his roster (163) when he was with Evolution (Zedeck I , Ex. B), which is not a Defendant in this case. (162 n. 217.) Moreover, the Court did not address 1) whether race is a factor a) i n how promotion relationships are developed (10,12); b) in how promoters are selected (18, 84); c) as to why Plaintiffs speciahze in R & B and urban music, not pop or rock (13, 48); d) when "familiarity with a specific genre o f music is important in selecting a concert promoter" (19) (cf. Lewis allowed Delsener to promote Badu (T3: 60); e) when "[a] promoter's financial capabiliries are . . . crucial" (19); f) in the financial success o f Rowe, Boseman and K i n g (50,53,55) (see Cronin v. Aetna Life Ins. Co.. 46 F.3d

-25-

196, 203 (2d Cir. 1995) (plaintiffs need not show that proffered reasons are false, but only that they were not the only reasons and that discrimination was A T L E A S T O N E o f the "motivating" factors)); 2) as to this critical criterion, Defendants' expert Mario Gonzalez W A S N O T A S K E D T O O P E V E , AND W A S I N S T R U C T E D B Y T H E D E F E N D A N T S N O T T O A N S W E R A N Y Q U E S T I O N S P E R T A I N I N G T H E R E T O (67-68,81,82;T4: 39-40); 3) not all o f the contracts with different terms between black and white promoters can be explained on the basis o f negotiation power (Haymon); 4) Rowe's alleged lack o f capital or record o f successful concert promotion (63): see Rowe's offer o f $300,000 for (29) Janet Jackson dates and C A A ' s tacit admission that Rowe can do the job because they've now offered h i m Gloria Estefan, etc. (156); 5) the "Financial Capabilities" o f Fred Jones: his gross income in 1997, 1998, 1999 was $900.000. $600-700.000. $588.000. respectively, and in 1999 he was worth more than $2.4 million (Jones 696-98); 6) Gonzalez testified that a) there are "predominant" promoters (Gonzalez 143,147), b) sometimes the agent calls the promoter about a date (id- 234), c) "there are times an agent does not put up a show for multiple bids"(id. 233), and d) in the 25 years he has been in the music industiy, the only majority-owned black promoter who has promoted a white act is Haymon, and the only reason he knows that is through Haymon's testimony (jd. 111 -13, 175-77); 7) with the exception o f one summer 1993 Steely Dan date, Haymon (as opposed to Haymony'SFX) has promoted no white artists during the relevant time period (Haymon 56-62); 8) there is no evidence that any B.A. Defendant has ever called a black promoter to notify him that a white act is going on tour; 9) B i l l Cosby testified that W M A selected 90% of his promoters (Cosby 53) ( E x . 16); 10) that the agency selects the promoter doesn't make "a hill of beans difference in the discrimination . . . . " (T3: 14-15, 16, 37, 39) ( c f 84,129, 132); 11) Kapp was convicted o f fraud and conversion after making false representations regarding his promotion o f a 1977 concert (Pis.' W M A , Ex. 153) (cf.(50-51)); 12) white promoter Richard Klotzman was convicted o f fraud, wire fraud, conversion, and income tax evasion related to a non-existent Prince concert, for which he was

-26-

sentenced to five years i n prison i n 1987 and i n 1979 was convicted of income tax evasion (served four months and fined $ 10,000) (id., Ex. 140 (cf. (50-51)); 13) W M A ' s Lewis continued to do business with Klotzman despite his criminal record and poor performance as a promoter (id., Ex. 93); 14) Cooley filed bankruptcy i n the mid 1970's and had a dispute with the IRS (Cooley 80,120-25(cf. (50)); 15) this Court stated, "[b]ids don't mean anything" (T3: 59) (cf. (passim)); 16) that even though allegedly "a promoter with familiarity in a specific geographic area or venue is preferred" (19), Beaver was brought in to Memphis, a market Beaver had stayed out o f (Leff letter), to promote James Taylor, a date that Jones would have promoted but for the interference o f Beaver and the "top talent agencies" (id.); 17) the reason Rowe stopped payment on the Jacksons' check was because the Jacksons owed Rowe money because o f their cancellations (Rowe 326); 18) Marlon Jackson attested to his experience with Rowe "as an excellent concert promoter" (Pis.' W M A , Ex. 100, f 7); 19) although the Court found that Jones has never submitted a bid to promote a white artist (56), he stood ready to promote James Taylor in 1998, but W M A refused to allow Taylor to play M u d Island and gave the concert to Beaver at another venue. No need to make an offer when to do so would be ftitile. (Int'l Bhd o f Teamsters. Dothard) (cf. 56); 20) it was Rowe's suggestion that Haymon use Braxton as the opening act for Frankie Beveriy i n 1995 (Pis.' C A A , Rowef214 (cf. 73); 21) W M A agent Jeff Frasco testified that Rowe was a qualified promoter (Frasco 64); 22) Jones is "[o]ne o f the best promoters out there today" (Sparks 29); 23) Rowe was among the major black promoters in certain territories (Kapp 74); 24) B i l l Washington cried at his deposition when he testified that black promoters "are not given the same opportunities that the white promoters are given" (43 -44) and also stated, 'Sve basically have not done any white acts . . . ." (Washington 152, emph. added); 25) Herenton issued a press release stating, "Fred Jones is a competent and well-respected promoter" (Pis.' Beaver, Ex. 1E); 26) Kapp has admitted that a) black promoters do not have the same opportunity to promote white artists as do black promoters, b) there's a prevailing prejudice held by artists, managers, promoters and agents against

-27-

black promoters w i t h respect to their promoting white artists, c) this racial prejudice has hindered the effort o f black promoters to be successful in the industry and, d) he does "not see a lot, i f any, black promoters promoting white talent" (Kapp 253-60); 27) just because C A A submitted contracts showing that some white promoters agreed to pay a 50% deposit (84 n. 122) (cf. Nederlander paid a 90/10 artist spHt (85 n. 113)), does not mean that blacks are not discriminated against when they must always pay 50%; 28) one o f the Plaintiffs' essential complaints is that they are allowed only to co-promote and do not sign the contracts with the artist, and, therefore, reap the majority o f the benefits o f each date. They, in essence, have to settle for scraps. I f the Defendants allowed black promoters, not

Haymon/SFX, to sign contracts promoting, not co-promoting, white and major black artists, just as the white promoters do, it would have been easy enough for them to prove. Since the Plaintiffs can't prove a negative, the burden to produce these "contracts," which the Plaintiffs requested, was on the Defendants; 29) that Haymon's company was SFX in 2000 (SFX owned 80%) (Haymon 23) is unrebutted, and whedier it was SFX i n 1999 (SFX owned 50%) (id.) was a j u r y question. That "after the purchases by SFX, [Haymon] ran the business in the same way" (id.) is irrelevant to whether the ownership interest was white or black, and that is the issue; 30) Billy Sparks testified that racisim pervades "[t]he whole system" which includes C A A (Sparks 22); 31) no agency in the last ten years has ever notified Sparks about a concert o f a white artist (id.24-27); 32) why, if there is no racial discrimination in the concert promotion industry, Haymon, a promoter who undisputedly meets ail of the Defendants' criteria, signed on to sue C A A and W M A , and believes that they have discriminated against him (Haymon 396-99,403,404,416-20,433,434, 449,489-91) ("it's polio or cancer, which one is worse" (id- 397)); and 33) this Court "weighfed] all the evidence in this case" (173)(passim) which it is not permitted to do on a motion for summary judgment. Although this Court has determined that hindsight now proves that Plaintiffs' allegations were not sufficient to survive summary judgment, as demonstrated above they were not "so bizarre as to be

-28-

frivolous."

See Tancredi v. Mefropolitan Life Ins. Co.. 378 F. 3d 220,229 {2d Cfr. 2004); Sullivan v.

School Board of Pinellas County. 773 F. 2d 1182, 1184, 1196 (11th Cfr. 1985) (unless court found all of plaintiff s testimony to be "absolutely incredible and pure fabrication, its fuiding o f frivolity cannot be sustained"). Moreover, when stripped o f its hyperbole, the Defendants' argument is only that

Plaintiffs' attorneys failed to "properly to investigate plaintiffs' claims before filing the action, and that they continued to prosecute those claims without sufficient evidentiary support. Flowever, there exists no 'clear evidence' that plaintiffs' claims were so preposterous as to warrant the conclusion that Plaintiffs' Coimsel engaged i n dilatory and abusive tactics or purposefully prolonged htigation of meridess claims." Simms v. Biondo. 158 F.R.D. 247 (B.D.N.Y. 1994); Browning v. Kramer. 931 F.2d 340,345 (5th Cir. 1991) (even when attorney continued to pursue claims after close of discovery when he should have known there was no evidence to support claims, 1927 sanctions are not required because "something more than a lack of merit is required for 1927 sanctions). '^ In addition, that the Court found that some o f the Plaintiffs' statements were untrue does not mean that they lied or were guilty o f bad faith. As this Court itself has stated (T2:6, emph. added): . . . It's like people s a y i n g . . . someone lied, well, because what they said was not accurate. That is not necessarily true, because they may not have reaUzed it wasn't accurate. It doesn't constitute a he i n my mind. People say it all the time. I even get it from lawyers.'' The Plaintiffs' attorneys' vigorous pursuit o f the Plaintiffs' claims showed their good faith belief the claims were valid, a belief that was repeatedly confirmed each time a Defendant settled with the Plaintiffs, by the Court's own statements, and by the numerous facts found i n the record. "Given these bases for the [Plaintiffs' and the Gary Firm's] subjective good faith in [Plaintiffs'] action, and in the absence o f any other evidence indicating an absence o f a genuine belief i n the validity o f the action,... the record cannot support an inference of bad faith [on their part]." Schlaifer Nance & Co.. Inc.. V . Warhol. 194 F.3d 323, 341 (2d Cir. 1999). To the contrary, a reasonable attorney could have

"*See Sperando Aff. ^1[4-7,11-17,18; William Campbell Aff. 7115-9 (Ex. 17) Rowe A f f . f l l Z - Z l . ''Plaintiffs admitted that the claim in the Amended Complaint that they represent the majority of business done by black concert promoters is false. (57 n. 91.) -29-