Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research of Poverty in Pakistan

Uploaded by

Salman MemonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research of Poverty in Pakistan

Uploaded by

Salman MemonCopyright:

Available Formats

IN Pakistans scenario, where approximately two-thirds of the people live in rural areas, rural poverty is a major destabilising factor.

Authoritative studies have documented rising poverty levels with a decreased capacity to acquire and hold land which is the main source of subsistence in the agricultural areas. Nearly 67 per cent of Pakistans households are landless (though this cannot in itself be taken to be the sole denominator of poverty in the country). The problem is thrown into sharp relief when compared to the decline in Indias rural poverty levels between 1987 and 2000. The comparison is pertinent since both countries inherited a nearly identical system of land holdings and feudalism. India seems to have tackled the issues better than Pakistan which appears to have alternated between monetary policies dictated by the IMF and the World Bank and its own experiments with land reforms which proved unsuccessful. The income disparity between the haves and have-nots in Pakistan has also increased significantly while income disparity largely became an urban phenomenon during the period under review. Since the reasons behind the rise of radicalisation are multifarious, an analysis utilising any single variable would be empirical, not to mention misleading. Nevertheless, whenever socioeconomic factors spring up in debates, the relationship between rural poverty and radicalisation figures quite prominently. Rural poverty was going down in Pakistan in the 1970s and 1980s but started increasing steadily during the 1990s. Although the methodologies and assumptions interpolated into the projection by a publicly funded Pakistani body are open to discussion, the poverty increase trend in the 1990s is alarming. The official notification points out that nearly 67 per cent of households owned no land at the time this study came out; 18.25 per cent households owned less than five acres of land; and 9.66 per cent owned between five and 12.5 acres, sufficient only to provide meagre levels of existence for sometimes large extended families that tend to rely on land as the sole source of income. The pattern is dismally skewed towards a few feudal families in possession of large land holdings; barely one per cent (0.64 per cent plus 0.37 per cent) of households owned over 35 acres.

Thus, the problem in Pakistan is not just low levels of land holdings but also highly unequal land distribution leading to a class of land haves and havenots. Strikingly, poverty levels tend to decrease in inverse proportion to landholdings, with poverty virtually disappearing with holdings of 55 acres and above. This indicates that poverty and landlessness are directly related to each other in Pakistans rural areas. In terms of the spatial distribution of landlessness, 86 per cent of the households in Sindh were landless (landless plus non-agricultural), followed by 78 per cent in Balochistan and 74 per cent in Punjab. The evidence of the income disparity rampant in Pakistani society is bolstered by statistics, with the Lorenz curve of 2001-02 for Pakistan lying below the 1984-85 levels. In economics, the Lorenz curve is often used to represent income distribution and can also be used to show the distribution of assets. This indicates that income distribution patterns have gradually worsened, resulting in higher income inequality in 2001-02 relative to 1984-85. Greater changes are visible in the higher part of the income distribution curves than in the middle and lower parts of the income brackets. This stipulates that during 2001-02, the upper income brackets registered a gain in income share to the richest 20 per cent at the expense of the poorest 20 per cent and middle 60 per cent. This increased poverty levels in the lower and middle brackets. This projection also indicates that the richest one per cent who used to get 10 per cent of the total income in 1984-85 was, in 2001-02, getting almost 20 per cent. It is estimated that in 1998-99, 30.6 per cent of Pakistanis were living below the poverty line. The estimate stands at 23.9 per cent in the period 2004-5, and according to official projections, dropped to 22.3 per cent by 2005-6. Rural poverty was estimated at 27 per cent in 2005-06, unfavourably comparing with an urban incidence of 13.1 per cent. The official surveys have, however, been criticised on the grounds of faulty methodologies and the padding of results. A World Bank survey put the figures of poverty incidence in Pakistan at 28.3 per cent in 2004-05, with income distribution patterns utilising the Gini coefficient yielding a figure of 0.3 in 200506 as compared to 0.27 in 2001-02. This indicates that there is a skewed income distribution pattern in favour of the high earners, which negates the

gains made in the eradication of absolute poverty by increasing income inequality. The overall poverty incidence was highest in Balochistan, with almost half the population living below the poverty line, with minimal difference between the poverty incidence in Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, once the Sindh data was adjusted for the skewed data patterns for rural poverty obtained by the inclusion of Karachi by comparing rural Sindh with rural Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Sindh figures rose to 38 per cent of the rural population living under the poverty line as compared to 27 per cent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Punjab fared the best, with an overall poverty incidence of 26 per cent and, anomalously, a rural poverty incidence of just 24 per cent. This also implies that rural poverty was lower than average in both Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab, which seems to militate against conventional wisdom and other studies. However, the problem is compounded once other variables such as lack of education, cultural and social paradigms are factored in, areas that need greater research in order to present a more meaningful picture of poverty in Pakistan.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Treasure House Is Within YouDocument69 pagesThe Treasure House Is Within Youblitzkrig100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Great Wealth PandemicDocument49 pagesGreat Wealth PandemicDennisNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Advanced Strategic Management Assignment IDocument6 pagesAdvanced Strategic Management Assignment IBura Ze100% (4)

- Legend:: Bonus Computation (Shortcut) ExampleDocument4 pagesLegend:: Bonus Computation (Shortcut) ExampleJeremyDream LimNo ratings yet

- Mintel 2030 Global Consumer Trends PDFDocument48 pagesMintel 2030 Global Consumer Trends PDFJosé LuizNo ratings yet

- Venus in 2nd HouseDocument1 pageVenus in 2nd HouseVedic Gemstone HealerNo ratings yet

- IGCSE Economics Self Assessment Exam Style Question's Answers - Section 5Document6 pagesIGCSE Economics Self Assessment Exam Style Question's Answers - Section 5DesreNo ratings yet

- Discuss global inequality and identify its context across different countriesDocument19 pagesDiscuss global inequality and identify its context across different countriesWinterson C. AmbionNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 (1) - ConsumptionDocument16 pagesChapter 2 (1) - ConsumptionKrIsHnArAjNo ratings yet

- 259 881 1 PBDocument14 pages259 881 1 PBRohimNurulHidayahNo ratings yet

- Mochamad Difa Satrio Wicaksono - 170810190004 - Kelompok 14Document6 pagesMochamad Difa Satrio Wicaksono - 170810190004 - Kelompok 14Difa SatrioNo ratings yet

- Glossary: Dr. I. Thiagarajan & Chitra RangamaniDocument38 pagesGlossary: Dr. I. Thiagarajan & Chitra RangamaniantroidNo ratings yet

- Todaro N Smith - CH 5Document13 pagesTodaro N Smith - CH 5Shrishti AgnihotriNo ratings yet

- Savings and Women Involvement in Business in Kasese District A Case of Women Entrepreneurs in Hima Town CouncilDocument7 pagesSavings and Women Involvement in Business in Kasese District A Case of Women Entrepreneurs in Hima Town CouncilKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Drain of WealthDocument1 pageDrain of WealthDibyendu Twipz BiswasNo ratings yet

- Adam SmithDocument20 pagesAdam Smithpratik shindeNo ratings yet

- The Constitutional and Social Context of Agrarian ReformDocument11 pagesThe Constitutional and Social Context of Agrarian ReformAnonymous XsaqDYDNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Definition of InsuranceDocument40 pagesMeaning and Definition of InsurancekanikaNo ratings yet

- Guaranteed Returns Financial Planning Dhan VriddhiDocument12 pagesGuaranteed Returns Financial Planning Dhan VriddhiSucharita Dashing SuchuNo ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of Closing The Racial Wealth GapDocument20 pagesThe Economic Impact of Closing The Racial Wealth Gapokmaya_2000788No ratings yet

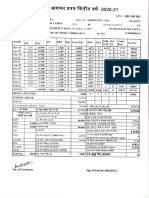

- Income Tax Agadan PrapatraDocument3 pagesIncome Tax Agadan Prapatraat.amitkumarbstNo ratings yet

- The Possible Misdiagnosis of A Crisis: PerspectivesDocument6 pagesThe Possible Misdiagnosis of A Crisis: PerspectivesthecoolharshNo ratings yet

- Stress Management Project-FHSDocument63 pagesStress Management Project-FHSSrujana Addanki100% (1)

- On MoneyDocument11 pagesOn MoneySenpaiNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management'Document99 pagesPortfolio Management'sumesh894No ratings yet

- What Distinguishes Money From Other Assets in The Economy?: Week 3 QuestionsDocument6 pagesWhat Distinguishes Money From Other Assets in The Economy?: Week 3 QuestionsWaqar AmjadNo ratings yet

- Taylor - Dependency Redux Why Africa Is Not RisingDocument19 pagesTaylor - Dependency Redux Why Africa Is Not RisingCherieNo ratings yet

- Unit-7 Environmental Approaches PDFDocument13 pagesUnit-7 Environmental Approaches PDFPavan Kalyan100% (1)

- Problem 1: 1.1Document7 pagesProblem 1: 1.1Janna Mari FriasNo ratings yet

- ACCT550 Homework Week 2Document5 pagesACCT550 Homework Week 2Natasha Declan100% (2)