Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Monetary Policy Economics A Level Study Notes

Uploaded by

jannerickCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Monetary Policy Economics A Level Study Notes

Uploaded by

jannerickCopyright:

Available Formats

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy involves changes in the base (policy) rate of interest to influence the growth of AD, the money supply, output, jobs and inflation. Monetary policy works by changing the rate of growth of demand for money; changes in short term interest rates affect the spending and savings behaviour of households and businesses and therefore feed through the circular flow of income and spending. The transmission mechanism of monetary policy works with variable time lags depending on the interest elasticity of demand for different goods and services. Because of the time lags involved in setting an appropriate level of short-term interest rates, in the UK the Bank of England sets rates on the basis of hitting the inflation target over a two year forecasting horizon. There are signs during the current recession that the usual transmission mechanism of monetary policy may have broken down. Independence for the Bank The Bank of England has been independent of the Government since 1997. In that time there has been several cycles of changes in interest rates. They have varied from 0.5% (since the winter of 2008-09) to 7.5% in the autumn of 1997. Monetary Policy and the Exchange Rate There is no official exchange rate target for the UK economy. The UK operates within a floating exchange rate system and has done since we suspended our membership of the European exchange rate mechanism (the ERM) in September 1992. That said interest rates still have an effect on the demand and supply of currencies in the foreign exchange rate markets. Monetary policy and the money supply There are currently no targets for the growth of the money supply. In addition the UK no longer imposes supply-side controls on the growth of bank lending and consumer credit. Since the spring of 2009 the Bank of England has operated a policy of quantitative easing as a tool of monetary policy.

Monetary Policy Interest Rates in the UK

Percentage - set by the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee

16.0

16.0

14.0

14.0

12.0

12.0

10.0

Percent

10.0

8.0

8.0

6.0

6.0

4.0

4.0

2.0

2.0

0.0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10

0.0

Source: Bank of England

The policy rate (or base rate) is shown in the chart above the chart is sometimes known as the Manhattan skyline! Nominal interest rates were very high during the 1970s and 1980s but since 1993 they have been more stable. The sudden and sharp reduction in policy rates was the dramatic response of central banks to the credit crunch and ensuing global recession. How does the Bank of England set interest rates? The BOE influences interest rates via daily intervention in the London money markets. Each day there are huge flows of money from the government to banks and vice versa. Usually more money flows from the banks to the government - for example people and companies paying their income tax - so, each day there is a shortage in the market. The BOE is the main provider of liquidity to the wider financial system, in the markets it is known as the lender of last resort. It can choose the interest rate it wishes to charge to financial institutions requiring money. The interest rate at which the BOE is prepared to lend to the financial system is quickly passed on, influencing interest rates in the whole economy - for example the rate of interest on mortgages and the rates on offer to savers. These interventions are sometimes called open market operations. Open market operations are where the Bank of England sells short-term government securities and bills. This will reduce the liquid assets of the banks and raise interest rates. If the government sells large amounts of gilts, this will mean a transfer of funds from the banking sector to the Bank of England. This will limit the ability of the banks to create credit and therefore limit the growth in the money supply. What is quantitative easing and has it worked? On Wednesday 11th March 2009 the Bank of England started a policy of quantitative easing (QE) for the first time. QE is also called as asset purchase scheme. The aim of QE is clear to support the growth of demand in the economy and prevent a period when inflation is persistently below target or becomes negative (deflation). Rather than acting on the short-term price of money through changes in the policy rate, the Bank of England can use quantitative easing to act on the quantity of money. The media call this printing money but this is only true in an electronic sense the Bank will not actually print new 10, 20 and 50 notes in a direct attempt to inject cash into the economic system. Under this unconventional strategy, the MPC discusses each month how many assets, including government bonds, to buy with central bank money. This money is simply created by the central bank and is the equivalent of turning on the printing press. At the time of writing, the MPC is authorised to buy up assets financed by central bank money up to a maximum of 150bn but that up to 50bn of that should be used to purchase private sector assets. QE is a deliberate expansion of the central bank's balance sheet and the monetary base. A rising demand for bonds and other assets ought to drive up their price and lead to a fall in long-term interest rates (yields) on such assets. (There is an inverse relationship between bond prices and bond yields). If long-term interest rates fall and the banks have stronger balance sheets because of BoE purchases under QE, the hope is that this will stimulate lending and stronger growth of business and consumer demand in the economy.

Number of loans approved for UK house purchase

Monthly figure, seasonally adjusted

130000 120000 110000 100000 90000 130000 120000 110000 100000 90000 80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 Jan Apr Jul 06 Oct Jan Apr Jul 07 Oct Jan Apr Jul 08 Oct Jan Apr Jul 09 Oct Jan Apr 10

Number of

80000 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000

Source: Council for Mortgage Lenders

In practice the Bank of England has been purchasing UK government bonds and with the government having a huge budget deficit, there have been plenty of bonds to buy! The evidence on QE so far has been mixed. Asset purchases have improved the liquidity of banks and pension funds but some commentators argue that the banks have been happy to sit on the cash and hoard it rather than use it as the basis for new lending to businesses and consumers. Credit availability remains low in the aftermath of the credit crunch and there are plenty of signs that banks and building societies have tightened the conditions on which they are prepared to give out new loans, overdrafts and mortgages. (i) Households have realised the true extent of their over-borrowing in the last decade and have decided to save extra income or repay debt, they are unlikely to respond to an increased availability of credit made possible by QE The banks themselves are still engaged in a process of de-leveraging that means they are desperate to reduce the amount of toxic debt they still have before starting to lend out again. Banks are cautious about future lending in the wake of significant losses arising from the financial crisis.

(ii)

Evidence that QE has been relatively ineffective in the short term comes from data on the UK money supply. The underlying growth rate of the M4 money supply, which comprises notes and coins in circulation, total bank deposits and loans to companies and individuals slowed down during the late spring and early summer of 2009. QE has been tried in other countries including the United States. And it became an important part of the policy of the Bank of Japan to drag their economy out of a deflationary slump in the 1990s. The European Central Bank (ECB) has been more reluctant to use QE during the present slump. Following the introduction of quantitative easing in March 2009, UK monetary policy now works through price and quantity this is an important change. Forward-looking monetary policy

Monetary policy in Britain is designed to be pro-active and forward-looking because changes in interest rates take time to work through the economy. The belief is that by making interest rate changes in a pre-emptive fashion, the scale of interest rate changes needed to meet the inflation target will be reduced. Factors considered by the Monetary Policy Committee At each of their rate-setting meetings the members of the MPC consider a huge amount of information on the state of the economy. Here are some of the factors they consider when making rate decisions. o o o GDP growth and spare capacity: The rate of growth of GDP and the size of the output gap. Their main task is to set monetary policy so that AD grows in line with productive potential. Bank lending and consumer credit figures including the levels of equity withdrawal from the housing market and also data on credit card lending. Equity markets (share prices) and house prices - both are considered important in determining household wealth, which then feeds through to borrowing and retail spending. The monetary policy committee has no official target for the annual rate of house price inflation but it has been criticised for not doing enough to prevent the housing bubble during the first eight years of present decade. Consumer confidence and business confidence confidence surveys can provide advance warning of turning points in the economic cycle. These are called leading indicators. The growth of wages, average earnings and unit labour costs. Wage inflation might be a cause of cost-push inflation. Unemployment figures and survey evidence on the scale of shortages of skilled labour. Trends in global foreign exchange markets a weaker exchange rate could be seen as a threat to inflation because it raises the prices of imported goods and services. Forward looking indices such as the Purchasing Managers Index and surveys of business confidence from the Confederation of British Industry and the British Chambers of Commerce International data including recent developments in the Euro Zone, emerging market countries and the United States.

o o o o o

The neutral rate of interest One important feature of interest rate setting both in the UK and overseas is the concept of a neutral rate of interest. The idea behind this is that there might be a rate of interest that neither deliberately seeks to stimulate AD and growth, nor deliberately seeks to weaken growth from its current level. There cannot be an exact measure of the neutral rate, and it will certainly differ from country to country.

Interest Rates for the UK and the USA

Per Cent

8.0 Bank of England Rates 7.0 USA Interest Rates

7.0 8.0

6.0

6.0

5.0

Percent

5.0

4.0

4.0

3.0

3.0

2.0

2.0

1.0

1.0

0.0 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10

0.0

Source: Reuters EcoWin

Market interest rates E.g. savings rates & credit cards Domestic Demand I.e. C + I + G Asset prices e.g. housing Aggregate Demand Official Interest Rate Net Business Expectations and Consumer Confidence External Demand i.e. X - M Import Prices Consumer Price Value of the exchange rate Inflation Domestic Inflationary Pressure

2009-10 a policy of ultra-low interest rates By the summer of 2009 the policy rate in the UK was 0.5% and the Bank of England had reached the point of no return when it comes to cutting interest rates. The decision to reduce official base rates to their minimum was in response to evidence of a deepening recession and fears of sustained price

deflation. Ultra-low interest rates are an example of accommodatory monetary policy i.e. a policy designed to deliberately boost aggregate demand and output. Can ultra-low interest rates prevent a slump? In theory cutting nominal interest rates close to zero provides a big monetary stimulus to the economy: Mortgage payers have less interest to pay increasing their effective disposable income Cheaper loans should provide a possible floor for house prices in the property market Businesses will be under less pressure to meet interest payments on their loans The cost of consumer credit should fall encouraging the purchase of big-ticket items such as a new car or kitchen Lower interest rates might cause a depreciation of sterling thereby boosting the competitiveness of the export sector Lower rates are designed to boost consumer and business confidence

But some analysts argue that in current economic circumstances, the usual transmission mechanism for monetary policy may have broken down and that cutting interest rates has little impact initially on demand, production and prices. Several reasons have been put forward for this: (i) (ii) (iii) The unwillingness of banks to lend most banks are de-leveraging (cutting the size of loan books) Banks have been reluctant to pass base rate cuts onto consumers and there is little incentive to lend when interest rates are at such low levels Low consumer confidence people are not prepared to commit to major purchases recession has made people risk averse as unemployment rises. Weak expectations lower the effect of rate changes on consumer demand i.e. there is a low interest elasticity of demand. Huge levels of debt still need to be paid off including 200bn on credit cards (v) Falling asset prices and expectations that property prices will continue to fall

(iv)

UK Output Gap and Base Interest Rates

Output Gap = Actual GDP - Potential GDP; Base interest rates set by the MPC

7.5

Interest rates

7.5

5.0

5.0

2.5

Per cent

2.5

0.0

Zero output gap along this line

0.0

-2.5

-2.5

-5.0

-5.0

-7.5 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

-7.5

Source: Reuters EcoWin

Monetary Policy and the Output Gap Puzzle (Tom White) With the immediate sense of crisis behind us, the chances of a downward spiral of deflation and economic activity have diminished. But our economy certainly has a large output gap. This is the difference between actual economic output and the most the economy could produce given the factors of production available. When actual output exceeds potential the demand for products and labour bids up prices and wages, fuelling inflation. When actual output falls short, competition for scarce sales and jobs puts downward pressure on inflation. But how big is our output gap? How do you really gauge a firms capacity, especially in services? How many of those not working could work? How fast is productivity growing over time? Economic shocks make the task even harder. They may render big chunks of our capital stock redundant: many idle car factories or steel plants, for example, may never reopen. Workers thrown out of a shrunken industry like finance or construction may take years to retrain for another. Some may never succeed. Although unemployed, they are not really competing for the jobs that fall vacant and are thus not putting much downward pressure on wages. That means the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or the NAIRU, may have risen. In other words, when actual output falls, it can drag potential output down with it. It is widely held amongst economists that if a country has a relatively rigid labour market, it means someone who loses a job will take much longer to find another. Britain is seen to have a fairly flexible labour market, so hopefully the NAIRU should remain fairly low. Potential output should stay in place, awaiting a smooth, rapid recovery. But doubt over the size of the output gap poses a big problem when the Bank of England thinks through its monetary policy decisions. They must not stimulate the economy too much, which they might do if they overestimate the size of the output gap. The opposite risk is that if they underestimate the size of the gap, it could allow inflation to completely melt away even risking the

spectre of deflation. This is even worse than the problem of inflation and can have a devastating impact. Japan suffered this fate and suffered a lost decade of low growth. The OECD notes that when Finland and Canada experienced large and persistent output gaps in the 1990s, inflation fell quite far but did not become deflation, which it puts down to the success of central banks in anchoring expectations with inflation targets. Britain has had such a target since 1997. Inflation or deflation may be avoided if firms and households have become convinced that the price level is now relatively stable, and behave accordingly. A significant part of Japans problem was that when deflation became entrenched, people acted accordingly. They slashed spending and investment in what became a self fulfilling deflationary cycle. Perhaps the Bank of England should risk overestimating the size of our output gap and keep up the stimulus until recovery is beyond doubt.

The Liquidity Trap In the 1930s, Keynes referred to a liquidity trap effect a situation where the central bank cannot lower nominal interest rates any lower and where conventional monetary policy loses its ability to impact on spending. The Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman has defined the liquidity trap as a situation in which conventional monetary policy loses all traction. When interest rates are close to zero as they are in the UK, the USA and in the Euro Zone, people may expect little or no real rate of return on their financial investments, they may choose instead simply to hoard cash rather than investing it. This causes a fall in the velocity of circulation of money and means that an expansionary monetary policy appears to become impotent. This means that different approaches are called for in order to stabilise demand in an economy on the verge of a depression: 1. Quantitative easing 2. A deliberate expansion of fiscal policy I.e. higher government spending and borrowing 3. Possible direct intervention in the currency markets to drive the value of the currency lower to boost exports (the Swiss government did this in March 2009)

Monetary Policy Asymmetry Fluctuations in interest rates do not have a uniform impact on the economy. Some industries are more affected by interest rate changes than others for example exporters and industries connected to the housing market. And, some regions of the British economy are also more sensitive to a change in the direction of interest rates. The markets that are most affected by changes in interest rates are those where demand is interest elastic in other words, demand responds elastically to a change in interest rates or indirectly through changes in the exchange rate. Good examples of interest-sensitive industries include those directly linked to demand conditions in the housing market exporters of manufactured goods, the construction industry and leisure services. In contrast, the demand for basic foods and utilities is less affected by short-term fluctuations in interest rates and is affected more by changes in commodity prices such as oil and gas. A (partial) return to credit controls? In the wake of the borrowing bubble and subsequent recession, it is likely that the Bank of England will exert tighter control on lending by financial institutions in the years to come. For many years the supply of credit available through loans, overdrafts, mortgages and other forms of lending has been determined by the markets and not by direct credit controls. This may change although the precise

form of prudential control is yet to be decided. Counter-cyclical credit controls would seek to constrain lending during economic booms but allow lending to be relaxed during a downturn / slowdown. Some of the options include: 1. Limits on bank lending relative to the amount of capital they hold (a form of cash to bank deposits ratio) 2. Loan to valuation ratios - limits on the amounts that banks are allowed to lend to housebuyers, relative to their income. 3. Supplementary taxes on loans that could be used to limit lending in a boom These controls would be in addition to the existing instruments of monetary policy.

You might also like

- Economic Growth: Costs and Benefits - Economics A-LevelDocument6 pagesEconomic Growth: Costs and Benefits - Economics A-LeveljannerickNo ratings yet

- What Is A Rating Agency - BBCDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Rating Agency - BBCjannerickNo ratings yet

- What Is Protectionism?Document7 pagesWhat Is Protectionism?jannerickNo ratings yet

- Why The Recession Benefits Small Shops - The GuardianDocument2 pagesWhy The Recession Benefits Small Shops - The GuardianjannerickNo ratings yet

- Conflict Mediation & Privatising Peace. The EconomistDocument3 pagesConflict Mediation & Privatising Peace. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Why The Germans Are Turning Against The EU - TelegraphDocument4 pagesWhy The Germans Are Turning Against The EU - TelegraphjannerickNo ratings yet

- A Question of Management. The EconomistDocument4 pagesA Question of Management. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Credit Agencies Criticised - BBCDocument2 pagesCredit Agencies Criticised - BBCjannerickNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Political Correctness Is Good For Business - TelegraphDocument2 pagesPolitical Correctness Is Good For Business - TelegraphjannerickNo ratings yet

- How The Private Sector Could Rescue Greece - TelegraphDocument3 pagesHow The Private Sector Could Rescue Greece - TelegraphjannerickNo ratings yet

- Stagnation or Inequality. The EconomistDocument3 pagesStagnation or Inequality. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Linear ProgrammingDocument18 pagesLinear ProgrammingjebishaNo ratings yet

- Stagnation or Inequality. The EconomistDocument3 pagesStagnation or Inequality. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Doha Talks - The EconomistDocument3 pagesDoha Talks - The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Economic Growth: Costs and Benefits - Economics A-LevelDocument6 pagesEconomic Growth: Costs and Benefits - Economics A-LeveljannerickNo ratings yet

- Bonuses Put Banks at Greater Risk - BBCDocument2 pagesBonuses Put Banks at Greater Risk - BBCjannerickNo ratings yet

- A Question of Management. The EconomistDocument4 pagesA Question of Management. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Credit Agencies Criticised - BBCDocument2 pagesCredit Agencies Criticised - BBCjannerickNo ratings yet

- Conflict Mediation & Privatising Peace. The EconomistDocument3 pagesConflict Mediation & Privatising Peace. The EconomistjannerickNo ratings yet

- Migration and The UK Economy - A Level EconomicsDocument4 pagesMigration and The UK Economy - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Deflation - A Level EconomicsDocument3 pagesDeflation - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- The Economic Cycle - A-Level EconomicsDocument11 pagesThe Economic Cycle - A-Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Fiscal Policy - Taxation and Public Expenditure - A Level EconomicsDocument15 pagesFiscal Policy - Taxation and Public Expenditure - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Economic Shocks and Their Effects - A Level EconomicsDocument9 pagesEconomic Shocks and Their Effects - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Migration and The UK Economy - A Level EconomicsDocument4 pagesMigration and The UK Economy - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- The Balance of Payments - A Level EconomicsDocument10 pagesThe Balance of Payments - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Monetarism - A Level EconomicsDocument3 pagesMonetarism - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Theory of International Trade - A Level EconomicsDocument9 pagesTheory of International Trade - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- Flexible Labour Markets - A Level EconomicsDocument3 pagesFlexible Labour Markets - A Level EconomicsjannerickNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- MetalTek Where Used GuideDocument18 pagesMetalTek Where Used GuidekakaNo ratings yet

- More From Macrina Recipe SamplerDocument14 pagesMore From Macrina Recipe SamplerSasquatch Books100% (2)

- Systems Analysis and Design Feasibility Study TypesDocument34 pagesSystems Analysis and Design Feasibility Study TypesMr.Nigght FuryNo ratings yet

- Solution: Elementary Differential Equations, Section 02, Prof. Loftin, Test 2Document3 pagesSolution: Elementary Differential Equations, Section 02, Prof. Loftin, Test 2DEBASIS SAHOONo ratings yet

- DplynetDocument312 pagesDplynetPhạm TuânNo ratings yet

- BDE - PPTX (1) - AnsweredDocument6 pagesBDE - PPTX (1) - AnsweredPookieNo ratings yet

- Music Assignment 1Document3 pagesMusic Assignment 1Rubina Devi DHOOMUNNo ratings yet

- MVix ManualDocument102 pagesMVix Manualspyros_peiraiasNo ratings yet

- MSE 440/540 Surface Processing LecturesDocument38 pagesMSE 440/540 Surface Processing LecturesrustyryanbradNo ratings yet

- (FS PPT) (Quantum Computation)Document22 pages(FS PPT) (Quantum Computation)21IT117 PATEL RAHI PINKALKUMARNo ratings yet

- Atec Av32opd Chassis Vcb4430Document42 pagesAtec Av32opd Chassis Vcb4430Radames Chibas EstradaNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice ManagementDocument3 pagesProfessional Practice ManagementMohit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Part Test - 3 (Senior) Question Paper 2011-P1 8-6-2020-FDocument15 pagesPart Test - 3 (Senior) Question Paper 2011-P1 8-6-2020-FJainNo ratings yet

- Walkie TalkieDocument1 pageWalkie TalkieYohan RahmadaniNo ratings yet

- Great Britain: Numbers Issued 1840 To 1910Document42 pagesGreat Britain: Numbers Issued 1840 To 1910Ahmed Mohamed Badawy50% (2)

- Machine Learning With Go - Second EditionDocument314 pagesMachine Learning With Go - Second EditionJustin HuynhNo ratings yet

- Bioquell Price List - 2017Document1 pageBioquell Price List - 2017Hardik ModiNo ratings yet

- Development of Automatic Temperature Control Brooder System For ChicksDocument73 pagesDevelopment of Automatic Temperature Control Brooder System For ChicksEJ D. ManlangitNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Manufacturing Engineering and Technology 7th Edition Kalpakjian Solutions Manual PDFDocument15 pagesDwnload Full Manufacturing Engineering and Technology 7th Edition Kalpakjian Solutions Manual PDFkhondvarletrycth100% (8)

- Deployment of A Self-Expanding Stent Inside An Artery (FEA)Document11 pagesDeployment of A Self-Expanding Stent Inside An Artery (FEA)LogicAndFacts ChannelNo ratings yet

- Optical RPM Sensor ManualDocument4 pagesOptical RPM Sensor ManualpepeladazoNo ratings yet

- Timss & Pisa Models: Khalidah AhmadDocument51 pagesTimss & Pisa Models: Khalidah AhmadMirahmad FadzlyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document4 pagesChapter 4KrisTine May LoloyNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic CleaningDocument9 pagesUltrasonic Cleaningfgdgrte gdfsgdNo ratings yet

- Documentation Tree PlantingDocument12 pagesDocumentation Tree PlantingLloydDagsilNo ratings yet

- User's Manual: WS-4830SS WS-4836SSDocument16 pagesUser's Manual: WS-4830SS WS-4836SSMarco TosiniNo ratings yet

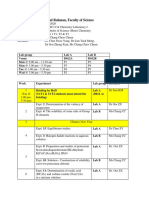

- UTAR Faculty of Science Chemistry Lab SessionsDocument3 pagesUTAR Faculty of Science Chemistry Lab SessionsYong LiNo ratings yet

- 12th Five - Year Plan 2012 - 2017Document3 pages12th Five - Year Plan 2012 - 2017workingaboNo ratings yet

- 2018 Analisis Perbandingan Pendapatan Usahatani Padi Organik Dan Anorganik Di Kecamatan Seputih Banyak Kabupaten Lampung Tengah (Leksono, Tri Budi., Supriyadi., Dan Zulkarnain)Document11 pages2018 Analisis Perbandingan Pendapatan Usahatani Padi Organik Dan Anorganik Di Kecamatan Seputih Banyak Kabupaten Lampung Tengah (Leksono, Tri Budi., Supriyadi., Dan Zulkarnain)Bagus gunawanNo ratings yet

- Gmp-Man-5 0 2 PDFDocument145 pagesGmp-Man-5 0 2 PDFMefnd MhmdNo ratings yet