Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Criterion Vol. 2 No. 3

Uploaded by

mumtazulhasanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Criterion Vol. 2 No. 3

Uploaded by

mumtazulhasanCopyright:

Available Formats

Using trade as a driver of political stability

Criterion

Volume 2 July - Sep. 2007 Number 3

Using Trade as a Driver of Political Stability: Prospects in the Indo-Pak Context

(Moeed Yusuf)

Pakistan: On or Off? Examining the Future of U.S.-Pakistan Relations in the War on Terror and Beyond (Farhana Ali) The Parliamentary System in South Asia Fundamentalism, Extremism and Islam OIC Retrospect and Prospects The Shia of Iraq and the South Asian Connection Turning on the Faucets of Thought (A.G. Noorani) (Prof. Dr. Anis Ahmad) (Tayyab Siddiqui) (Khaled Ahmed) (Anjum Niaz)

34 58 89 106 129 141

Criterion

Founder S. Iftikhar Murshed Publisher and Editor-in-Chief S. Mushq Murshed Executive Adviser Riaz Khokhar Adviser Aziz Ahmad Khan Editors Muzaffar Abbas (Executive) Navid Zafar (Research) Printers Lawyersown Press 28, alfalah Askaria Plaza, Committee Chowk, Rawalpindi. Contact Editor The Criterion House 225, Street 33, F-10/1, Islamabad Tel: +92-51-2210531 Fax: +92-51-2297206 Criterion is a quarterly magazine which aims at producing well researched articles for a discerning readership. The editorial board is neutral in its stance. The opinions expressed are those of the writers. Contributions are edited for reasons of style or clarity. Great care is taken that such editing does not affect the theme of the article or cramp its style. Quotations from the magazine can be made by any publisher as long as they are properly acknowledged. We would also appreciate if we are informed. Subscription: Pakistan, Bangladesh & India Rs. 195 (Local Currency) Overseas US $ 15 The Subscription Price is Rs. 700 & US $ 50 plus postage Price: Rs 195 US $ 15

Using trade as a driver of political stability

USING TRADE AS A DRIVER OF POLITICAL STABILITY: PROSPECTS IN THE INDO-PAK CONTEXT (Moeed Yusuf)*

Abstract (While countries all over the world are fast harvesting the fruits of open trade policies, Pakistan and India, in spite of sharing a common history of thousands of years, have failed to reap the benets from the new trade openings. The message that these two large countries in the region have given to the world is that no condence building measure will prove effective, unless a political solution of Kashmir creates a feeling of relief for the entire region. In the present state of political stalemate India, being the bigger country remains the major loser.Editor) 1. Introduction1 The last two decades are marked by signicant progress in terms of attaining a globalized economy. Barriers to inter-state trade have come down drastically. Pundits of free trade continue to promote economic liberalization not only as a means to accrue economic benets, but also as a tool for peace building. The contention is that economic integration can raise the opportunity cost of conict to prohibitive levels, thus leading to political stability among trading partners. Recent literature has argued for the potential of utilizing economic integration to address conict between the two South Asian giants, India and Pakistan. The two countries, by virtue of their enormous populations, sensitive geo-strategic locations, and nuclear weapons capability maintain signicant leverage in statecraft. Yet, the two have been held back from realizing their true potential due to historically turbulent bilateral relations. Periodic conict and crises have impacted all aspects of their relationship. Economic interaction has been one of the casualties, with trade ows remaining minimal. This is despite the fact that Pakistan and India (including Bangladesh) were a common economy merely sixty years ago. While efforts at political reconciliation have continued over the years, the conict resolution paradigm has never allowed out of the box thinking from either side. Resultantly, both sides have remained intransigent, rendering their stances on key contentious issues irreconcilable. In this backdrop, peace theorists have been arguing for Pakistan and India

* Moeed Yusuf is a research fellow at the Strategic and Economic Policy Research (Pvt. Ltd.) in Islambad.

Criterion

to adopt the economic interdependence course by working towards developing robust trade ties as a means to ameliorate conict. Indeed, progress on this front is already underway as Pakistan and India are currently in the midst of a composite peace process, whereby they have agreed to allow simultaneous movement on all contentious fronts, including trade. The ongoing bid for rapprochement has raised realistic hopes of attaining a positive spin-off from enhanced economic interaction in terms of political stabilization. While the euphoria around the possibility of economic interdependence providing an answer to Indo-Pak political tensions remains alive, hardly any concrete analysis has been conducted to examine the realistic potential. This paper seeks to ll the void by analyzing the potential for enhanced economic interaction between Pakistan and India to impact bilateral tensions positively. The rst question to address is whether trade can be raised to meaningful levels. If so, can trade ties be congured so that they raise the cost of conict prohibitively and nudge both sides towards political normalization? Section 2 sets out the conceptual framework for the analysis. Section 3 provides a background of political and economic relations between Pakistan and India. Section 4 evaluates the potential for Indo-Pak trade to increase to meaningful levels. Section 5 discusses the various barriers to enhancing bilateral trade. Section 6 establishes the linkage between trade and conict in the Indo-Pak context in order to determine whether a positive spin off from trade is realistic. Section 7 provides a prognosis for the future. 2. Conceptual Framework2

Extensive literature exists on the multi-faceted impact of trade liberalization on inter-state relations. The economic theory of interdependence- the theoretical debate which examines the relationship between trade and peace- has matured considerably over the past decade. Two major schools of thought have emerged. The current drive towards employing economic interaction as a means of ameliorating conict is grounded within the liberal theory of economic interdependence, proponents of which argue that trade is inherently benecial as it brings efciency gains for producers, consumers, and governments.3 The argument is that trading arrangements bring about political stability by increasing interdependence. By enhancing the economic incentive for peace, interdependence leads to amelioration of inter-state conict. Empirical evidence from across the world suggests the liberal theorists remain more relevant to countries where conicts are minor or in cases where conict mediation has already progressed to a certain degree through political or diplomatic means.4 More relevant to the context of countries with long-standing conicts that

Using trade as a driver of political stability

are highly complex in nature and where little tangible progress has been possible is the international relations theory. Theorists subscribing to this school suggest that trade by itself is not sufcient to ensure the absence of conict. Proponents argue that the decision to trade depends on the potential returns from trade and the future expectations of the level of trade within a foreseeable time frame. Copeland (1996), arguing along these lines, suggests that high interdependence can be either peace-inducing or war-inducing depending on the expectations of future trade.5 In essence, theorists subscribing to the international relations theory contest that a states choice between conict and trade would be based on relative trade benets, and not absolute gains as trade theory suggests. If a country perceives the other to gain much more from trading, it would deem it in its interest not to liberalize trade. Matthews (1996) puts forth this argument contending that it is essential for states to look at relative gains from trade before entering into trade arrangements.6 An extremely important nuance to the debate is the issue of trade reaching a critical level. Indeed, even liberal trade theorists do not expect a positive spin-off from trade by the mere presence of trading relations between states. As Andreatta, et al (2000) argue, for the liberal contention to work, there needs to be a certain threshold of economic interdependence that must be achieved.7 Extending the argument, Andreatta et al, suggest that a certain level of institutional development is necessary if such a threshold is to be achieved. The latter can be translated into the need not only for interaction in terms of volume, but also for integration of production processes and economic structure between countries which would develop an intrinsic link between production of a particular product or provision of a certain service. In other words, process integration is a key variable which ought to complement interaction in volume terms for the trade-to-peace causality to function. In the subsequent discussion, we situate our argument within the economic theory of interdependence, applying the conceptual premise to the Indo-Pak context to explore the trade-conict linkage. We shall focus on the international relations school of thought given its greater applicability to situations fraught with inherent complexities, and ones where virtually no tangible progress has been made over an extended period of time. 3. 3.1 An overview of Pakistan-India relations8

Political relations Pakistan - India political tensions date back to a bitter partition which divided the Indian sub-continent into two independent states, Pakistan and India at the cost of widespread violence and tremendous loss of civilian life. The two countries continued on the path of hostility after partition, and were involved in armed conicts

Criterion

in 1948 and 1965, the underlying cause being the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir, which has undoubtedly proven to be the most consequential contention between the two sides over the years. Both conicts ended in a stalemate, without either side gaining a decisive advantage.9 In 1971, a secessionist movement in East Pakistan was actively supported by India. The short Indo-Pak war that followed resulted in the dismemberment of East Pakistan.10 Since 1971, the two countries have found themselves in the midst of several near-war situations. At least four crises of note occurred in 1986-87, 1990, 1999, and 2001-02.11 The last two took place under the South Asian nuclear umbrella, thus underscoring the potential dangers of Indo-Pak hostilities. The history of conict between the two sides is also extended beyond purely inter-state conicts. Both sides have continuously blamed each other for internal strife within their respective borders. The most serious intrusion by Pakistan was in the ongoing insurgency in Indian occupied Kashmir where Pakistan allegedly provided material and training support to the insurgents.12 India also claims ISI involvement in the Khalistan movement a Sikh drive for independence in Indias Punjab province during the 1980s.13 Moreover, Pakistan has remained a strong critic of the plight of Indian Muslims.14 Although no direct Pakistani involvement in Indias communal problems has been alleged, Hindu-Muslim riots do lead to tensions between the two countries. The fact that communal incidents have been commonplace throughout Indias history has ensured that diplomatic tensions on this count have been permanent. Pakistan, on its part, has not been shy of pointing to Indias hand in strife within its borders. Indian involvement in the 1971 affair has already been alluded to. Pakistan also blamed India for supporting acts of sectarian and ethnic violence across the country in the 1990s, especially in the troubled city of Karachi.15 RAWs hand in bomb blasts across the rest of the country have also been established in several cases.16 In fact, Global Security has listed a long list of terrorist activities within Pakistan in which Indian involvement is believed to be present. At present, Pakistan is alleging an Indian role in the ongoing Baloch insurgency.17 Table 1: Chronology of India-Pakistan tensions

Inter-state conict Inter-state crises Intra-state conict relevant to the adversary Pakistan 1948-49 1965 1987 1990 East Pakistan (1971) Sindh violence (1990s) India North-East insurgency (1950s) Khalistan movement (1980s)

Using trade as a driver of political stability

1971

1999 2001-02

Balochistan insurgency Kashmir insurgency (1989-present) (2004-present)

Source: Compilation from various sources [originally prepared by the author and presented in Khan et al., Managing Trade, 2007].

Reasons for Indo-Pak conicts are many and complex. While some attribute conicts solely to territorial and possession disputes through rather simplistic arguments, more substantial variables have been at play in exacerbating political tensions over time. First, Pakistan and India were born with irreconcilable ideologies. Although no Indo-Pak conict has been spurred due to ideological reasons, these have surely exacerbated mutual animosity. Perhaps the most negative role has been played by the states themselves who over time have consciously attempted to twist facts to expose the negative elements of the adversary.18 Second, governments on both sides have raised mutual hatred as a politically opportune tool. A dominant argument particularly relevant to Pakistan is the militarys use of anti-India rhetoric in a bid to maintain its clout in Pakistani policymaking. Indeed, the military has always ensured that the India-centric national security paradigm remains sacrosanct. Although it would be absurd to argue that the entire anti-India perception is a construction of the Pakistani establishment, there is certainly a strong lobby that continues to play up the Indian threat for institutional gains.19 In India, Hindu nationalist parties and activist factions have played an equally negative role. Within India, they remain irritated by Pakistans nuisance value and have used the anti-Pakistan rhetoric for political gains. At the same time, they have exposed Pakistans tactics of asymmetrical warfare as proof of Pakistans hostile designs and have thus justied their right to pursue coercive policies vis--vis Pakistan. Finally, Pakistan and India have historically been aligned to opposing blocks of power.20 The inuence of external actors on Indo-Pak hostilities has been mixed. On the one hand, external actors have assisted both sides in building up tremendous military assets. On the other, countries like the US have also restrained crises between the two sides by exerting diplomatic pressure. Nonetheless, external inuence on regional stability, which is intrinsically linked to the IndoPak equation, have been extremely negative off late. A glaring exampling is the severe internal backlash Pakistan has had to face, rst due to the Afghan Jihad and now due to the ongoing War on Terror campaign in Afghanistan. In the nal outcome, persistent tensions combined with the negative role of both states have led to an atmosphere of mistrust, where virtually no constructive interaction in any realm has been possible. In fact, nationalist voices on both sides portray any move to show leniency to the adversary as a sell-out, thus making the

Criterion

price of rapprochement politically prohibitive. 3.2 Trade relations The state of trade relations between the two sides is equally dismal. Interestingly, at the outset in 1947, by virtue of being a common economy before independence, Pakistan and India remained the single most important trade partner for each other. Till 1949, 32 percent of Pakistans total imports originated in India, while 56 percent of its total exports were destined for India.21 However, in 1949, once Pakistan refused to devalue its currency to reciprocate Indias move, mainly to prevent higher import costs, trade ties were abruptly slashed. Economic interaction between the two sides has remained minimal ever since. For much of the past decade for instance, despite some positive movement courtesy of the South Asian Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA), Indo-Pak trade has remained stagnant at less than one percent of their total global trade. Only in the last two years has the proportion increased somewhat. The overall balance has favored India consistently. Major trade items include petroleum products, yarn, chemicals and cotton by way of Pakistani exports, and chemicals, rubber, animal fodder, plastics, and iron and steel, by way of imports.22 Table 2: Indo-Pak trade statistics

PAKISTAN-INDIA TRADE STATISTICS YEAR EXPORTS IMPORTS (million US $) (million US $) 36.23 90.57 173.66 53.84 55.41 49.37 70.66 94.00 288.13 293.31 204.70 154.53 145.85 127.38 238.33 186.80 166.57 286.90 491.66 634.91 TRADE % OF TOTAL % OF TOTAL BALANCE EXPORTS FOR EXPORTS FOR (million US $) PAKISTAN INDIA (168.47) (63.98) 28.81 (73.74) (182.92) (137.44) (95.91) (192.9) (205.53) (341.60) 0.43 1.04 2.39 0.62 0.60 0.54 0.63 0.76 1.99 1.77 0.61 0.44 0.43 0.34 0.53 0.42 0.31 0.44 2.71 2.49

1996-97 1997-98 1998-99

23

1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06

Source: Foreign Trade Pattern of Pakistan, Karachi Chamber of Commerce and Industry; Trade Development Authority of Pakistan; Directorate General of Foreign Trade, India

Using trade as a driver of political stability

[originally prepared by the author for and a modied version presented in Khan et al., Managing Trade, 2007].

While dismal, formal trade patterns between Pakistan and India only provide a partial picture of overall trade ows. Both countries engage in substantial informal trade as well. The existence of informal trade is important not only to determine the true level of trade owing between the two sides but also because informal trading mechanisms often rely on robust integration patterns which institutionalize communication channels. The state of integration within these informal institutions could point to the potential of such integration being transferred to the formal ambit, should legal trade between Pakistan and India reach meaningful levels. Prior to a relatively recent comprehensive study by the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), conjectures of informal trade between the two sides grossly exaggerated the trade potential. Guesstimates oating around ranged between USD 0.5 billion and USD 10 billion, with the majority approximating the upper end of the spectrum.24 Findings from the SDPI study however pointed to a total informal trade volume of merely USD 0.54 billion. Bulk of the trade is conducted through smuggling routes across Afghanistan and not through quasi-legal routes through third ports as was previously believed. This has implications for gauging the potential for trade creation, as a mere switch from quasi-legal to formal channels would not have any impact on overall trade volumes of either Pakistan or India. In that sense, the nding of the above mentioned report is optimistic. However, the estimated volume only conforms to the lower end of the existing guesstimates. Thus the overall increase in formal trade predicted due to a switch from informal to formal channels is lower than what most proponents of Indo-Pak free trade predicted in the past.25 Another important fact revealed is that an overwhelming majority of informal trade ows from India to Pakistan. Pakistani exports to India constitute a mere USD 10.3 million. Even these are concentrated in commodities like cloth, dry fruits, and bed sheets, all items which have limited viability in terms of integration of production patterns between the two sides.26

Criterion

Table 3: Value of Informal Imports from India (000 USD)

Items DubaiBandar AbbasBara Cloth Livestock Medicines Pharmaceutical and textile machinery Electroplating chemicals Cosmetics and Jewellery Herbs and spices Ispaghol (husk) Big elachi Black hareer Betel Blankets Rickshaw/ Motorbike parts Tires Paan ghutka, Paan parag Indian razor blades Biri (cigarette) Others Total Value Sigma Total 156,850 119,376 1,000 72,282 3,306 2,225 8,572 5,070 95,700 97,500 55,440 534,516 480 7,150 500 2,500 5,000 5,000 250 20,000 6,250 1,350 8,500 3,825 2,880 40,280 1,600 18,250 75,000 128,000 Informal trade routes Dubai- DubaiDubai Sindh Delhi- Singapore- Total Bandar Karachi Karachi cross- Lahore Karachi value Abbas(In (Third border by item Chaman formal) country) 1,066 45,350 2,500 7,800 33,340 10,400 500 2,000 1,280 185,996 33,340 32,750 75,000

15,000 2,600 1,300 960 800

15,000 63,840 8,350 1,350 8,500 3,825 2,880 5,000 5,250 73,282 3,306 2,225 8,572 6,050

Source: Khan et al., Quantifying Informal Trade, 2005.

10

Using trade as a driver of political stability

Table 4: Source, Destination and Value of Informal Exports from Pakistan

(USD 000)

Items Dubai Karachi (Third country) Cloth Cigarettes Dry fruit Video games, CDs Footwear Prayer mat Bed Sheet Others Total Value Sigma Total 6,800 375 2,525 375 6,800 Informal trade routes Sind cross-border 1,775 Delhi-Lahore Total by item 520 100 52 100 52 52 135 30 1,041 10,366 52 52 135 405 9,095 100 427

Source: Khan et al., Quantifying Informal Trade, 2005.

Apart from trade in goods, there is hardly any economic interaction to speak of on either side. Virtually no trade in services has taken place thus far. Moreover, while there has been some recent talk of joint ventures and direct investment in each others country, no consequential progress has been achieved on ground. Recently, some measures to facilitate presence of each others banks and corporate ofces have been taken.27 However, again, there is not much to show for in terms of tangible gains. 4. The potential for enhancing trade: Reaching the critical level?28

The single most important prerequisite for the economic theory of interdependence to function is attaining a critical level of trade ows, both in terms of volume and integration of the economies in question. Both the liberal and the international relations schools of thought acknowledge the need to have sufciently robust trade ties. In the Indo-Pak context, existing literature is divided on the extent to which trade complementarities exist. Majority of the analyses point to high level of complementarities, suggesting that the present trade volume between the two sides is miniscule as compared to the true potential. Wickramasinghe (2001) and Burki (2004) indicate signicant trade complementarities.29 Not only do they point to the possibility of macro-level gains, but they also argue that increased trade

11

Criterion

ows are likely to bring about technical efciency, improve resource allocation and allow countries to create niches by specializing in different products or focusing on a particular stage along the value chain within a given industry. The latter points towards the possibility of integration of production structures. As for quantitative estimates, Mukherjee (1992) identied as many as 113 items for intraregional exports and a 110 items for intraregional imports within the SAARC region.30 Bulk of these are likely to be captured by Indo-Pak trade. Frankel and Wei (1997) indicate that trade between Pakistan and India is 70 percent lower than the levels two similar economies would be expected to have.31 A study by the World Bank suggested that an Indo-Pak free trade arrangement could increase bilateral trade ows nine-fold within a decade.32 Other optimistic estimates fall within the USD 5-10 billion range. Quite to the contrary, some equally convincing analyses point to a much more pessimistic picture. Aggarwal and Pandey (1992) point to an almost identical pattern of comparative advantage between Pakistan and India, albeit within a narrow band of commodities that have similar production structures.33 Pessimists argue that there are strong structural similarities in both economies that act as constraints to trade. Both sides exhibit a lack of capacity to generate exportable surpluses of products in accordance with regional specications and requirements. Decient capital for expanding on high value added exportable products has reduced both sides, especially Pakistan, to dependency on industrialized nations for capital goods and technology. Trade being tilted in this regard complicates efforts to integrate and increase regional self-sufciency, a fact that reects the current scenario in South Asia. A comprehensive set of studies conducted under a World Bank commissioned project provide the latest forecasts for some of the sectors traditionally believed to be potential drivers of Indo-Pak trade. The outlook is far from optimistic. Studies of the sugar, chemicals and light engineering sectors either point to a number of barriers that may restrict trade or underscore the lack of price competitiveness on either side.34 The study on textiles and clothing (T&C), perceived to be one of the key areas for future trade, suggests low trade potential in intermediate T&C. While the prognosis in nal consumer T&C is better, the study cautions that the outcome would depend on the amount of investment Indian rms are willing to make in Pakistan. Moreover, it points to the fact that under free trade conditions, Indo-Pak trade in T&C is likely to signify trade diversion rather than trade creation.35 4.1 Estimating trade potential Given the varying interpretations of the potential for Indo-Pak trade to grow,

12

Using trade as a driver of political stability

we have conducted a rudimentary statistical exercise ourselves. The analysis is not meant to accurately predict volumes. Instead, we simply seek to come up with a broad estimate to highlight whether Indo-Pak trade can reach meaningful levels.36 4.1.1 Potential for Pakistani exports Table 5 contains the current items and volumes of Pakistans exports to India as well as the calculations for the potential for trade, were trade ties completely liberalized. To do so, we take into account the maximum tradable volume. This is equivalent to the lower of the gures for Pakistans total exports to the rest of the world and Indian total imports from the rest of the world for each commodity (column 5). We do not take the higher of the two gures since that would reect a volume that is either greater than what the exporting country can produce or the importing country demands. Also important is to note that in the case of Pakistani exports, there are no formal bans on any commodities, which implies that all items with export potential are currently owing (although at a much smaller scale). Only two commodities, footwear and bed linen, are not exported formally but were recorded as major informally traded commodities. They have thus been included in the analysis. Table 5: Pakistani exports to India

USD million Items Current volume Total Pak. exports to ROW Total Indian imports from ROW Maximum exportable volume from Pakistan (smaller number between 3 and 4) 5

3 Formal trade

Petroleum products Yarn Organic chemicals Cotton Edible fruits, nuts Leather and articles thereof Synthetic textiles

96.87 80.53 36.48 28.12 27.88 20.22 13.83

825.65 1,382.87 432.83 2,108.48 229.41 945.63 200.30

20,500 438.09 5,144.21 438.09 787.09 332.73 127.33

825.65 438.09 432.83 438.09 229.41 332.73 127.33

13

Criterion

Edible Vegetables and 11.78 roots Fish and sh preparations 0.43

42.79 194.15 Informal trade

637.64 24.20

42.79 24.20

Footwear Bed linen, sheets Total

0.07 1.67 317.8837

142.22 2,038.06 8,542.39

92.61 107.06 28,629.05

92.61 107.06 3,090.79

Source: Federal Bureau of Statistics, Pakistan; Directorate General of Foreign Trade, India; Trade Development Authority of Pakistan; State Bank of Pakistan [originally prepared by the author for and presented in Khan et al., Managing Trade, 2007].

From table 3, the total potential for trade (if all Pakistani exports in tradable items were channeled to India keeping in mind the latters demand) comes to USD 3090.79 million. Now, given that expecting all of the Indian demand in these commodities to be met by Pakistani exports is unrealistic, we take a benchmark of 25 percent of this total exportable surplus to come to a more reasonable estimate. While our benchmark is notional, we have selected it given the fact that the proportion of total tradable volume exported from Pakistan to the US, which is its largest export destination, approximates the same percentage. This brings the predicted volume of Pakistani exports to India to USD 772.69 million. 4.1.2 Pakistani imports from India The case of Indian exports to Pakistan is more complex, as unlike the reverse ow, there is a ban on a large number of items to ow into Pakistan. Therefore, the liberalization of trade is likely to ow in three steps. First, the bans would be removed by providing India MFN status but tariff and non-tariff barriers will remain. Under this scenario, items currently traded informally would come within the formal ambit, and arguably the volume of these commodities would increase by a factor that is impossible to estimate. At the very least, a switch from informal to formal trade would bring the total trade volume to USD 1473.10 million, which is the total trade ow between the two sides at the moment. Table 6: Combined trade (2005-06)

(USD million) Total formal trade 928.22 Total informal trade 544.88 Combined trade 1473.10

Arguably, in the subsequent phase when a free trade environment ensues, the potential would be much higher. To estimate total trade potential, we follow the

14

Using trade as a driver of political stability

same methodology as in the case of Pakistani exports to India. However, here in addition to accounting for items traded informally, we also include commodities which are suggested to have high potential for export from India but are neither traded formally or informally at present. These constitute the items whose import is formally banned by Pakistan and are either too bulky or sensitive to be traded informally (capital machinery for example).

Table 7: Pakistani imports from India

USD million Items Current volume Total Indian exports to ROW Total Pakistani imports from ROW 4 Maximum importable volume from Pakistan 5

3 Formal trade

Organic chemicals

205.66

4,857.09 1,034.96 1,122.88 2,160.51 3,813.47 168.53 567.87 846.94 4,452.61 421.35 905.11

1,224.97 219.00 49.65 1,792.90 320.06 87.87 142.57 187.05 50.46 1091.14 222.55

1,224.97 219.00 49.65 1,792.90 320.06 87.87 142.57 187.05 50.46 421.35 222.55

Rubber and articles thereof 115.89 Animal fodder, waste from 54.01 food industries Plastics and articles Iron and steel Sugars Edible vegetables, roots Tanning and dyeing extracts Ores, slag, ash Oil seeds, Fruits, Grains, Medicinal plants Tea, coffee, mate, spices 44.89 32.63 30.48 30.47 20.55 19.90 13.63 12.01

Informal trade + commodities identied as potentially tradable Light engineering, machinery Cosmetics and Jewellery Buffaloes 75.00 63.84 33.34 2000.55 764.93 6.00 2601.00 123.98 2000.55 123.98 6.00

15

Criterion

Pharmaceuticals Chemicals (apart from organic) Auto parts Blankets Value-added textiles, silk TOTAL

32.75 15.00 5.25 5.00 751.96

38

2444.18 1079.06 252.92 87.56 11399.75 38,386.16

292.15 1365.80 N/A N/A 320.79 10,091.94

292.15 1079.06 252.92 87.56 320.79 8,881.44

Source: Federal Bureau of Statistics, Pakistan; Directorate General of Foreign Trade, India; Trade Development Authority of Pakistan; State Bank of Pakistan [originally prepared by the author for and presented in Khan et al., Managing Trade, 2007].

The total importable production in items which Pakistan would potentially demand from India comes to USD 8,881.44 million. Using the 25 percent benchmark, which again approximates the proportion of total tradable volume imported by Pakistan from its largest import partner, the UAE, our estimates for Indian imports to Pakistan come to USD 2,220.36 million.39 Our notional estimates put the potential for total Indo-Pak trade at USD 2,993.05 million. Proponents of Indo-Pak free trade could argue that data discrepancies and the rudimentary nature of the analysis may have induced a signicant error percentage, thus underestimating the true potential. Be that as it may, the entire point of this exercise was to rule out the concern about the potential for trade being low enough not to allow ties to reach meaningful levels. In absolute terms, even the estimated volume will make India one of Pakistans top ve trading partners. This would imply a robust enough relationship to satisfy the precondition for the economic interdependence theory to function, at least in volume terms. However, while prerequisites in terms of volume may end up being satised, what such a quantitative exercise fails to capture is the issue of integrated economic structures. Even a substantially high trade level like the one predicted above may prove futile in terms of impacting political tensions if sufcient integration of economic structures is not achieved. While existing literature is largely silent on this issue in the Indo-Pak context, an examination of the list of tradable items between the two countries (table 5 and 7) does not present an optimistic picture. Virtually all products are either primary goods (especially in the case of Pakistans exports) or nished products that allow for little integration in terms of production processes. Only a handful of input items such as textile machinery (included under light engineering, machinery in table 7) could create mutual interdependence. Moreover, most other projections of potential for integration, for instance through trade in services, joint ventures and investment in various sectors, remain idealistic.

16

Using trade as a driver of political stability

In reality, the Indo-Pak context is fraught with multiple technical and political barriers to trade, which are unlikely to allow the theoretical potential for trade to be realized on the ground. Barriers would impact both the potential for trade ties to progress in volume and integration terms. We turn to a detailed discussion of these barriers in the next section. 5. Barriers to enhancing Indo-Pak trade40

Several barriers confront Indo-Pak trade. The contention, as should be clear from the following discussion is that even if a consensus to enhance trade is reached in principal, there are signicant barriers that would dampen the potential for trade growth. We limit our discussion to barriers which have a bearing on trade potential to address political instability. 5.1 Barriers specic to the trade protocol To begin with, substantial formal barriers exist with the bilateral trade regime. Although both countries have liberalized their economies signicantly in recent decades, some undesired anomalies still remain. This is especially true for India. An IMF study rated Indias trade restrictiveness at 8 (on a scale from 1 to 10), while Pakistans index stood at a relatively better 6 (IMF, 2004). A World Bank study on trade regimes in South Asia found India to be in the top 10 percent closed economies on the basis of unweighted tariffs.41 Pakistan-India CEOs Business Forum alleges the Indian trade regime to be the least transparent in the region.42 Indeed, Indias nontariff barrier ratios are the highest in South Asia. India is also known to have used specic duties and high tariff peaks to protect a number of sectors. These include agriculture, textiles, and garments, among others.43 Moreover, India also maintains a convoluted domestic tax and subsidy structure which has caught the attention of trade experts not just within Pakistan, but across the region.44 Indias restrictive trade regime neutralizes any potential benets that Pakistan could accrue by virtue of the fact that New Delhi has accorded Pakistan MFN status. Pakistan, on its part, has negated any possible gains to India by virtue of Islamabads relatively more liberalized economy by its persistent refusal to grant India MFN status. Pakistans decision has deed trade logic and is situated within the realm of realist politics. Currently, Pakistan maintains a formal ban on imports of all Indian items except those on a 773-item strong positive list.45 Apart from formal trade barriers, both sides suffer from acute inefciencies in the implementation of their trade protocols. The result is a highly inefcient bureaucratic structure that causes inevitable delays in executing transactions. Indias protocol exhibits greater bottlenecks. Average transaction cost levels remain extremely high in both countries.46 The existence of high transaction costs increases

17

Criterion

the cost of trading signicantly, not only nancially but also in terms of additional time required to complete trade related formalities.47 Trade optimists could of course argue that the formal barriers merely require a consensus within decision makers to be removed. As for the procedural hurdles, they would contend that these too can be addressed once trade ties begin to show promise. While that may be so, one must consider that issues of procedural barriers and domestic subsidies, especially in Indias case are underpinned by deep structural anomalies in the Indian economy, and thus cannot be addressed immediately. That is why Indias trade protocol presents these barriers not only to Pakistan, but to the rest of the world as well. It is unrealistic to expect India to overhaul its subsidy structure in the short run, given its political ramications.48 Banking on changes over the long-run however, has implications for the likelihood of the economic theory of interdependence to function. As already mentioned, the international relations sub-set of the theory emphasizes the importance of relative gains and future projections within a foreseeable time period. Were Pakistan to grant India MFN status without any reciprocity from the Indian side in terms of removal of trade distortions, India is likely to benet disproportionately in the interim period. Given existing trends which point to a signicant positive Indian trade balance vis--vis Pakistan, this could imply a trade equation overwhelmingly in New Delhis favor. International relations theorists would predict that such a situation may prompt Pakistan to pull out of the trading arrangement. 5.2 The political economy of trade The fear of disparate gains for India is intrinsically linked to Indias overbearing economic size and is shared by the entire South Asian region. SAARC countries perceive themselves to be bound by a hub and spoke model, with India at the hub dictating intra-regional ties. India accounts for almost 76 percent of South Asian GNP, 64 percent of the export trade and 73.6 percent of the regions population.49 Given the sheer size of the Indian economy and its relatively advanced technological and industrial base, India undoubtedly stands to gain the most from intra-regional trade. Other South Asian countries, including Pakistan, fear their markets being ooded with Indian exports, and thus are wary of opening up to India. Existing literature on Pakistan and India points to a near-consensus on the fact that Indias export potential to Pakistan is much higher than the other way round. The current trade trend between Pakistan and India bears out this concern. Despite absence of an MFN status, Indias exports to Pakistan have grown as a percentage of its global exports, but its imports have remained low in comparison. Even the improvement in Indo-Pak ties over the past two years has

18

Using trade as a driver of political stability

assisted the Indian case disproportionately. Pakistans trade decit has grown from a mere USD 95.91 million in 2002-03 to USD 341.60 million in 2005-06.50 Our statistical exercise in the previous sections also pointed to a higher Indian export potential under a completely liberalized trade scenario. Another good proxy of Indias overwhelming advantage is the trend in informal trade. This is an important proxy since informal trade is conducted in items that are otherwise banned or too costly to trade, but have a potential market on the other side. As already mentioned, Pakistans current role in informal trade is miniscule compared to that of India.

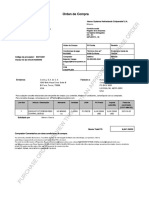

Figure 1: Pakistans balance of trade with India Pakistan's balance of trade with India

50 0

USD millio

-50 1996-97 -100 -150 -200 -250 -300 -350 -400

1998-99

2000-01

2002-03

2004-05

Year

In addition to the above, there is a need to account for the fact that Pakistans exports are likely to remain much lower than its theoretical potential in the initial years. This is so because Pakistans manufacturing industry is set up to cater for small-to-medium sized markets, and in most sectors is functioning near full capacity. Therefore, for the foreseeable future, Pakistan would not be able to utilize its advantage even in products in which it has a competitive edge. To the contrary, Indian exports to Pakistan could begin almost instantly, given the much larger production potential and ever growing capacity that allows India to adjust to new markets quickly.51 This implies a huge short-term impact on some of Pakistans less competitive industries. The impact would lead to closures/buy outs of inefcient (mostly small) units, with direct impact on employment, and in turn poverty. Notwithstanding vested interests, this is the ultimate fear of those opposing trade with India. Granted, the scenario could improve from Pakistans perspective if the country invests in key sectors for trade with India. However, this would require a

19

Criterion

virtual transformation in the production structures across various sectors, which is no mean feat to achieve in a scenario where government incentives are curtailed to a minimum due to resource constraints and where a rules based global trading regime seeks to limit government support. Moreover, reorienting production structures and sectoral priorities to complement the other side would also imply that a number of input industries would be rendered uncompetitive. This could lead to a loss of integration in the domestic value chain which has been painstakingly achieved by both sides over the years. To expect either side to compromise to this extent simply in the hope of a successful outcome a la the economic theory of interdependence is unrealistic. In any case, even if the momentum generated by the impetus to enhance trade nudges Pakistan to contemplate a move in such a direction, the contention of disparate gains and negative future projection in the interim period will act as a barrier. Another point is relevant here. The entire discussion thus far about trade potential between Pakistan and India in essence reects bilateral gains through trade diversion. No trade creation is envisioned in the short run. Even over the long term, the potential for trade creation from Pakistans side is questionable given the lack of surplus production capacity. With regard to trade diversion, prospects remain bleak in a scenario that is clearly fraught with mutual distrust and where past experiences point to unreliability of the adversary in terms of fullling trade obligations. Arguably, switching from current customers to trade with India (even if it entails slightly higher prots) is a high risk proposition in the current environment. The argument is substantiated by Pakistans bitter experiences with over-reliance on India in the past. Pakistan recalls the Indian move to cancel coal shipments during the 1965 Indo Pakistani war, a time when Pakistan was heavily dependant on India for its coal imports. Similarly, the potential for disruption of exports such as cotton in 1999 following the hijacking of an Indian airlines passenger jet (accusations of contaminated cotton from India prevented Pakistani cotton exports) also worry Pakistanis. The fear is also manifested on the Indian side. Indo-Pak discussions on the IPI gas pipeline are constrained by fears of Pakistan turning off the taps. Assurances from Pakistan that the pipeline will be isolated from bilateral tensions have been ignored.52 Even with the inclusion of stakeholders such as the World Bank, the Indian position has remained virtually unchanged. Business communities on both sides do reect the mutual mistrust. In Pakistan, the business community remains divided on whether Pakistan should open up trade ties with India. Personal discussions on the subject with inuential stakeholders suggest that they seem keen on establishing trade links only in areas that would benet them but remain extremely wary of allowing across-the-board

20

Using trade as a driver of political stability

trade.53 For example, an overwhelming majority supports allowing imports of raw materials from India but opposes trade in nished goods. Trade specialists realize that such a scenario is difcult to materialize if the MFN status is implemented in letter and spirit. Interestingly, most businessmen with prior experience of direct dealing with Indian counterparts reect a much higher level of suspicion.54 During our interviews, we were told of Indian authorities discriminating against Pakistani consignments. Indian customs authorities apparently delay Pakistani consignments as a means of neutralizing the formal MFN status India has granted to Pakistan.55 5.3 Extra-regionalism The prospects of Indo-Pak trade are also dampened somewhat by a concerted drive from both sides to look towards extra-regional states as principal partners. In part, this has been induced by lack of meaningful intra-regional trade. The attention of Indian policy advisors has been conveniently turned to more lucrative markets (the look East policy) abroad In fact, some Indian policy makers have promoted the argument that the structural similarities between India and Pakistan do not allow for signicant amounts of trade. Rather, India would be better off by opening up trade with East and South East Asia. It is thus not surprising to note that Indias major trading partners are ASEAN + 3 (China, Japan and Korea) accounting for 19.9% of merchandise trade, and EU and North America with 19% and 12.9% share respectively.56 India is also a member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperative Organization, Bangkok Agreement, KUNMING Initiative, Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand Economic Cooperative, and East Asia Summit, and enjoys a healthy relationship with the Association of South East Asian Nations. Pakistan, while having been less successful in its look West policy in terms of approaching Middle Eastern and Central Asian Republics, still maintains bulk of its trade ties with the North. Its major partners are the EU and the US, accounting for nearly half of its exports.57 The extra-regional focus implies lack of any serious compulsions on the part of either India or Pakistan to pursue bilateral trade with vigor. The intra-regional trading arrangements also present an interesting picture. Despite its primary focus on extra-regional sources, India has carefully crafted sub-regional alliances with South Asian states. Consequently, trade related subregional arrangements are peculiar in that Pakistan is left out from almost all of them. The Sub- Regional Cooperation in the East South Asia Sub region (ESAS), South Asia Sub Region for Economic Cooperative (SASEC), and South Asia Growth Quadrangle (SAGQ) all involve India, but not Pakistan. In essence, subregional groups threaten to ostracize Pakistan further. Under such a scenario, Pakistans hopes of continuing to play a major role in South Asian economic

21

Criterion

affairs lie in the recently implemented South Asian Free Trade Agreement for the most part. Again, there are doubts on SAFTAs ability to provide comparable gains. The India dominance syndrome is very much apparent and is forcing all other regional countries to negotiate hard on the composition of the sensitive lists that would allow protection of commodities included in the list.58 Pessimists also raise concern about SAFTAs impact on trade complementarities between member states. The contention is that trade complementarities would be further reduced given that SAARC countries are pursuing extra-regional exports and inviting FDI from Trans-national Corporations (TNCs). The export oriented industries while generating additional complementarities with the rest of the world are in fact causing additional competition within SAARC member states.59 Others, while acknowledging the potential for SAFTA to have a positive impact within the region still hold that SAARC countries would benet more from unilateral trade liberalization rather than functioning within an RTA, which gives preferential treatment to RTA members.60 Moreover, the argument about South Asian states competing for foreign investment to the region also partially questions the optimism surrounding intra-regional investment potential. Again, the only country that may be able to venture in cross-border investment in South Asia is India. The concerns about disparate gains, and in the case of sub-regional groupings, of Indias designs to isolate Pakistan again make international relations theorists on economic interdependence relevant. 6. Exploring the trade-conict linkage61

Thus far we have established that while theoretically the potential for robust trade ties exists, there are serious challenges to attaining tangible positive change both in terms of increasing trade volumes as well as fostering integration of economic structures. However, the chicken-and-egg problem we started with still remains. Is it trade that will help in ameliorating political tensions, or do tensions need to be resolved through other means before trade can take-off. In this section, we try to establish the linkage between trade and political tensions within the IndoPak context. We conduct a qualitative analysis along a time-line to decipher our answer by establishing the timing of various efforts at political rapprochement versus that of trade agreements. While the most obvious way to test the relationship between political events and trade ties would be to document major bilateral political developments and trade volumes in the corresponding periods, there is an inherent problem to this approach. The foremost concern is that while political tensions can be tracked in real-time, trade volumes often reect lagged impacts of moves made in the past. In a scenario as volatile as the Indo-Pakistan bilateral relationship,

22

Using trade as a driver of political stability

pinpointing the correlation between two specic events would be virtually impossible. In order to make the analysis more meaningful then, we track political relations at a point in time against formal moves towards enhancing economic ties. The latter are signied by trade agreements. These would provide a better proxy to reect the mindset of the two countries at a particular point in time. Below, we mention the major agreements (also including those relevant to trade facilitation) and highlight the political context in which they were concluded, as well as the political events that followed. Indeed, an analysis along a timeline establishes a strong relationship between political rapprochement, positive trade related movements, and tensions that stymie any potential impact of developments on the trade front. The trend has been for political conciliation to lead to positive movements on trade, but for recurring political tensions to stall the possibility of any potential economic benets from such movements. Inevitably, the two countries have landed back where they started from each time. 1.1 Documenting the events Agreement for the avoidance of double taxation of income between the Government of the Dominion of India and Pakistan (December 1947). As already mentioned in section 3.2, Pakistan and India were major trading partners at the time of independence in 1947. The agreement to avoid double taxation was signed in that spirit. However, just months after independence, the two countries found themselves embroiled in an active conict over the disputed territory of Kashmir. The conict left no doubt that the two sides were unlikely to be able to reconcile differences over the short-run. Political tensions manifested themselves in the trade ambit, when in 1949, using Indias devaluation of its currency and Pakistans refusal to do so as the basis, trade ties were severely curtailed. Indo-Pakistan Trade agreement (January 1957) The 1957 agreement was the rst in a decade. The agreement was made possible by the absence of active conict after the cease-re in Kashmir was reached in 1949. In between, good will agreements seeking to safeguard places of worship (Pant-Mirza Agreement to prevent border incidents and protect places of worship) and prevent mass exodus of minorities induced a thaw in tensions. Moreover, while the Kashmir dispute remained unresolved, Pakistan and India had managed to nd an uneasy truce after a decade of co-existence. However the mutual distrust still remained deeply entrenched. Therefore, while a trade

23

Criterion

agreement was concluded, it was limited in scope and only valid for a period of three years, reecting a cautious, test-and-see approach on both sides. Agreement with Pakistan on trade (March 1960) In 1958, a military coup in Pakistan brought the Chief of the Army to power. The overt absence of democracy, which in any case had been fragile in Pakistan ever since independence, did not allow the distrust to disappear. In fact, Pakistan strengthened its hard-core realist view of the Indian State, which automatically kept the two sides from negotiating on Kashmir in a spirit of compromise. Despite this however, there was no overt change in the ofcial India policy from Pakistan. Consequently, the 1957 agreement was extended, but only for another three years. Trade Agreement with Pakistan (September 1963) The status quo remained between 1957-60. The trade agreement was again extended for three years, albeit for the last time. Developments after the event clearly point to the linkage between political tensions and trade. The military regimes realist view and utter frustration with lack of tangible progress on Kashmir, for which Pakistan by and large continued to muster international support, Pakistan sought to force the issue militarily. In 1965, Pakistan and India were embroiled in a military conict courtesy of Pakistans intervention in Indian occupied Kashmir and New Delhis exaggerated response on the international border. The result was a virtual stalling of trade ties and the de facto expiry of the 1963 agreement. Agreement on Bilateral Relations between India and Pakistan signed at Simla (July 1972) Relations between Pakistan and India reached their nadir after the 1971 IndoPak war and the dismemberment of East Pakistan. All trade relations, the little that continued after the 1965 debacle, were instantly halted. However, left with little choice but to accept the nal outcome as permanent, Pakistan and India signed the 1972 Simla Agreement. The Agreement was holistic in nature and stressed the need to reinitiate trade ties.62 However, political relations remained cold. Protocol on the resumption of trade between India and Pakistan (November 1974); Protocol on Resumption of Shipping Services between India and Pakistan (January 1975); Trade Agreement with Pakistan (January 1975). Within two years however, the impetus gained from the Simla Agreement led both sides to reach out in various areas. That Pakistan and India ofcially signed a new trade protocol in 1974 and signed a shipping protocol and a fresh trade agreement a year later is thus no coincidence. Both sides agreed to reinitiate trade ties, and by virtue of these protocols actually managed on-ground progress in

24

Using trade as a driver of political stability

commercial exchanges. Interestingly, political tensions remained, but were pushed to the backburner. This situation was not affected even by a fresh military coup in Pakistan in 1977. Creation of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) (1985) Once the immediate fallout of the 1971 debacle had withered away and trade ties were restored, Pakistan took a more realistic stance on Kashmir, even signing an accord on Kashmir (which did not amount to much) in 1975. Absence of active conict, Pakistans outright focus on Afghanistan at the time, and the potential losses of staying out of a South Asian regional forum led to both agreeing to be included in SAARC, which was created in 1985. Some commentators have also argued that both sides saw SAARC as an opportunity to gain regional prominence at the expense of the other, and thus agreed to the idea as a move in their respective countrys strategic interests. While SAARC came into existence, the progress in integrating regional states was minimal. Pakistan lacked democracy as well as a consensus on the countrys approach towards India. The two sides found themselves in the midst of a crisis in 1987, which all but stalled relations again. However, towards the end of the military rule in 1987, and especially with the return of democracy to Pakistan in 1988, efforts towards a composite relationship were reinitiated. Agreement between India and Pakistan for the Avoidance of double taxation of income derived from International Air Transport (December 1988) This trade facilitation move was a result of the attempts by the respective leaders of Pakistan and India at the time, Prime Ministers Benazir Bhutto and Rajiv Ghandi to attempt rapprochement. As mentioned, their effort was in part prompted by a severe crisis- the Brasstacks- in 1987 which brought the two sides to the brink of war as well as the fact that democracy had returned to Pakistan after 11 years. The Lahore Declaration (February 1999) It is striking to note that during the 1990s, when Indo-Pak relations remained tense on various counts, not a single trade agreement was signed. Rather interestingly, this is despite the fact that elected governments remained in power throughout the 1990s, albeit with frequent military interventions behind the scenes and almost persistent political turmoil. The Lahore Declaration signed in 1999 was largely a result of an attempt to remove political differences and suggested that cooperation in all spheres would be achieved. For the rst time in a decade, the region was euphoric about the possibility of openness in relations. However, the

25

Criterion

effort was stymied even before it got off the ground by the 1999 crisis in Indian occupied Kashmir and the resultant mini-war between Pakistan and India. Another crisis followed two years later once the Pakistani military took over the reigns of the country yet again. The Pakistan-India Composite Dialogue Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayees Hand of Friendship speech in April 2003 led to the initiation of a fresh peace bid, the effort in 1999 having been stalled by two major crises in 1999 and 2001-02.63 Trade ties form an important pillar of the current Composite Dialogue that grew out of Vajpayees invitation for reconciliation. The Dialogue has for the rst time taken a parallel approach to discussing all issues of mutual interest. Pakistan has nally agreed to move away from its Kashmir rst stance and discuss issues such as commercial ties concurrently. As part of the Dialogue, Pakistan and India are now regularly exchanging Commissions and holding meetings on various aspects of trade and trade facilitation. Some of the important exchanges are listed below: Meeting of Foreign Ministers of both countries at the ASEAN Regional forum where Pakistan is formally accepted as a member of the ARF after India drops its objections (June-July 2004). Meeting of commerce secretaries in Islamabad to discuss economic and commercial cooperation (August 2004). Pakistan accepted 25 tons of food, medicine, tents, blankets, plastic sheets from India after the earthquake (October-November 2005) Pakistan-India resumed train service at Khokhrapar-Monabao after 40 years (February 2006) Agreement to revive trade in Kashmir (May 2006) This agreement signies the efforts taking place on both sides specically to redress the plight in Kashmir. Subsequent to this agreement the two sides agreed to trade raw products between divided regions of Jammu and Kashmir. No manufactured items have thus far been allowed.64 Both countries agreed to sign a Revised Shipping Protocol (October 2006) South Asia Free Trade Agreement Signed (SAFTA) (January 2004) One spin-off of the composite dialogue was that SAFTA was nalized signed in January 2004. The agreement which had been agreed in principal a decade ago and was supposed to be implemented by 2001, continued to be delayed in the wake of Indo-Pak tensions.65 The thaw in relations nally gave an opportunity to the regional members to ink the deal. The timing of SAFTA in relation to the state of Indo-Pak relations also underscores the geo-political weight the two countries

26

Using trade as a driver of political stability

carry in the region. The above discussion presents a clear trend in the linkage between political and trade related events between the two sides. Without exception, each trade agreement between Pakistan and India can be traced back to positive movements on the political front. In fact, even the scope of trade agreements in part has been a result of the kind of political atmosphere that existed at the time. This was clear from the narrow scope and periodic short-term extensions of the 1957 trade agreement. By the same token, the Indo-Pak history shows that political tensions emanating at a time when a trade arrangement was operational invariably ended up directly impacting trade ties, in some cases stalling commercial exchanges completely. Such a cyclical relationship has continued unabated. Clearly, the direction of the linkage ows from conict-to-trade, quite the opposite of what is required for the economic theory of interdependence to function. 7. Searching for hope

Our analysis presents a bleak picture with regard to the potential of enhanced trade ties to ameliorate Indo-Pak political tensions. First, trade growth is impeded by substantial barriers, some of which may lead to a bilateral trade regime which by its very nature undermines the potential for any positive spin-offs (due to disparate gains and negative future projections on Pakistans part). Second, the direction of the trade-conict linkage ows from conict to trade, implying that easing of political tensions would have to precede meaningful trade. In other words, it is trade that has been held hostage to conict over the years rather than the other way round. As is being widely portrayed, the future of the Indo-Pak relationship to a large extent depends on the outcome of the ongoing composite peace dialogue. Indeed, this is the rst time both sides have allowed all contentious issues to be discussed simultaneously with a seeming resolve to make progress irreversible. Trade optimists draw hope from the fact that the two countries, de facto, have ended up employing the liberal theory of economic interdependence. In other words, the perception is that trade is being accorded a chance to play a role in overall rapprochement. Such optimism is misplaced not only because of the reverse direction of the trade-conict linkage, but also because the Dialogue framework contains within it a serious structural anomaly, one that calls for parallel movement on political and trade issues but without removing the linkages between the two. The fact remains that while Pakistan has agreed to experiment with a parallel approach, it has been categorical in maintaining that the progress on Kashmir must be comparable to that in other spheres.66 Pakistans insistence on linking trade with other outstanding issues distorts the trade theory model, a formulation which

27

Criterion

is inherently sequential in nature as it requires a reasonable level of economic facilitation to have taken place before any impact on conict-ridden issues could be realized. Moreover, while trade volumes are being raised, structural impediments and institutional barriers to trade are not being addressed. In that sense, the gains have deliberately been kept narrow. Furthermore, the political front is completely stagnant. Increasingly then, one is beginning to witness tensions resurface. Certainly, if progress is not made on political issues, which in all likelihood seems to be the case, progress on trade might also be reversed.67 This ows directly out of our nding that political tensions historically have impacted movements on the trade front negatively. For the Indo-Pak equation to have any chance of improving in tangible terms, the formulation of the composite dialogue framework must be reoriented. What is required is a bottom-up trust building exercise that would gradually build a mass momentum in support of bilateral normalization. It is only then that vested interests would be undermined and tangible progress could be expected on all counts. Key in this regard is the presence of an enabling environment. Specically, this includes unlimited interaction between the two peoples, an atmosphere of trust between them which would ow from such interaction and predictability in relations over the long run. Interestingly, the Indo-Pak peace process began on the right footing. There were substantial overtures from both sides to enhance people-to-people contact. The idea was to build a constituency for peace to create trust and give condence to the masses of the permanence of the relationship. In retrospect, however, while interaction may have increased, the focus has skewed. The emphasis has remained limited to holding concerts, fashion shows, cricket, and other sporting events. No doubt, these are positive developments. However, they only allow a select number of people to interact, for the most part the elite, and that too with numerous restrictions. Their impact on creating a mass constituency for peace is marginal. Given the lack of interaction at present, there is no question of any trust developing between the two sides. The current state also implies lack of predictability, which makes any long-term relationship nearly impossible. This is especially true for trade ties, as business communities almost inevitably tend to shy away from unpredictable environments.68 The upshot is that genuine compulsions to improve ties exist on both sides. Therefore, were a reorientation of priorities to take place within the Dialogue framework, a number of exogenous and endogenous factors may well nudge the two sides towards a historic breakthrough. Economically, both sides share need for natural resources. Both Pakistan and India remain heavily decient in energy and an even greater shortfall is predicted for both sides in years to come. While

28

Using trade as a driver of political stability

projects such as the IPI have hit roadblocks, in an environment that has managed to foster a reasonable level of trust, such projects could well become the drivers of structural integration between the two sides. The benets of cooperating within the larger energy sector are also tremendous. Similar is the case of water resources and the need for both sides to nd amicable arrangement to continue sharing water channels. Politically, from Indias point of view, moving forward on Kashmir will build condence of its neighbors. There is also increasing realization in India that its quest for global status is unlikely to be realized if its conict with Pakistan continues unabated. The excessive defense expenditure, the reluctance of the international community to offer India a permanent Security Council seat without prior resolution of disputes with Pakistan, and other similar factors act as visible impediments to its ability to move from a regional to a global status. Domestically, there are heavy pressures on Indias political leadership to sustain economic growth, which if anything is held back due to resources being diverted to sustain the conict with Pakistan. Pakistans motives have been analyzed as being indicative of a need for respite having endured years of conict and deterioration in its own security environment. Pakistani literature on development is increasingly being couched in the guns versus butter argument, with the development enclave increasingly imposing its views on policy makers. While it has not changed the stance of the military elite, one is beginning to see tremendous importance being accorded to economic growth and development sector needs. Moreover, past policies of cross-border subversion have become excessively risky in the post-9/11 geo-strategic scenario confronting South Asia. A return to the past is unrealistic for Islamabad to contemplate. From the perspective of Indo-Pak relations, this implies absence of the traditional sticking point of cross border subversion, and thus improved chances of peace. The role of the external actors is also important. In the aftermath of 9/11, India and Pakistan have shifted the focus of their foreign and defense policies from self-serving, unilaterally motivated stances to supportive and cooperative efforts for the global ght against terrorism. This policy shift has been largely due to the necessity of political cooperation and assistance, but also due to the large amounts of economic aid that are being invested in countries that are key participants in the new security order. By virtue of its objectives, the war on terrorism will continue to require increased transparency, trust, and collaboration, particularly in Afghanistans neighborhood. In an area with such a history of prolonged conict and turmoil, it will be fundamental for India and Pakistan to advance their relationship beyond the stalemate over Kashmir and the terrorism that has proliferated within their borders. This complements the objectives of the

29

Criterion

international community, which is desperate to see the two nuclear armed rivals move away from conict.

REFERENCES

1 This paper draws heavily upon two research undertakings that the author has co-authored previously. These are (i) Shaheen Ra Khan, Faisal Haq Shaheen, Moeed Yusuf, and Azka Tanveer, Regional Integration, Trade and Conict in South Asia, Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), August 2007; (ii) Shaheen Ra Khan, Faisal Haq Shaheen, and Moeed Yusuf, Managing Conict Through Trade: The Case of Pakistan and India, Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), February 2007. Arguments extracted from these papers have been explicitly attributed throughout the text. However, since the author has co-authored these papers, individual citations in the present undertaking have been attributed to their original sources. The author originally contributed a modied version of this section to Khan et al., Regional Integration, Trade and Conict, 2007. For a succinct discussion of the theoretical premise, see Peter Robson, The Economics of International Integration (London: Routeledge, 1998). Also see, S. Akbar Zaidi, Issues in Pakistans Economy (Karachi: Oxford University Press,2004). The liberal approach is substantiated by developments in Europe and Latin America for example. Dale C. Copeland, Economic Interdependence and War: A Theory of Trade Expectations, International Security, Vol. 20, No. 4, 1996. John C. Matthews III, Current Gains and Future Outcomes: When Commutative Relative Gains Matter, International Security, Vol. 21, No 1, 1996. Filippo Andreatta, Pier Giorgio Ardeni, and Arrigo Pallotti, Swords and Plowshares: Regional Trade Agreements and Political Conict in Africa, paper presented at a workshop on New Forms of Integration in Emerging Africa, Geneva, October 13, 2000. The author originally contributed some of the arguments in this section to Khan et al., Managing Conict through Trade, 2007. Devin Hagerty, The Consequences of Nuclear Proliferation: Lessons from South Asia (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998), pp.67; 69-70. Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose, War and Secession: Pakistan, India, and the Creation of Bangladesh (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), pp.221-234. For a brief overview to the crises, see Moeed Yusuf, Stabilization of the Nuclear Regime in South Asia, South Asia Journal, Vol. 7, January-March, 2005. Stephen P. Cohen, The Jihadist Threat to Pakistan, The Washington Quarterly, Summer 2003, vol. 26 no. 3, 2003. R.J. Kozicki, The Changed World of South Asia: Afghanistan, Pakistan and India after September 11, Asia Pacic Perspectives, Volume 2, No. 2, May 2002, University of San Francisco Center for the Pacic Rim; S. Bhatt, Chronicle of Terrorism Now Told, Rediff Special, Rediff Online, 8 October, 2002. Pakistan has direct relevance to the communal problem in India, given that protection for minorities was a formal part of the spirit of partition. Prime Ministers of India and Pakistan signed the famous Nehru-Liaqat Pact in 1950 which obligated protection of minorities in both countries.

2 3

4 5 6 7

8 9 10 11 12 13

14

30

Using trade as a driver of political stability

15 16

17 18 19

20

21

22 23 24 25 26 27 28

29

30

31

32 33

Shereen Mazari, Subversion and its Linkage to Low Intensity Conicts, Ethnic Movements and Violence, Defense Journal, Vol. 3 No. 4, April 1999. The latest proof is the death sentence upheld by the Supreme Court of Pakistan against a RAW agent for having engineered bombings in various Pakistan cities in 1990. The defendant pled guilty. See Pak SC Upholds Death to RAW Agent, Hindustan Times, August 19, 2005. <http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/7598_1466178>. Proofs of RAWs Involvement in Balochistans Mayhem Delivered to India, Pak Tribune, June 1, 2006. <http://www.paktribune.com/news/index.php?id=145447>. Ahmed Saleem and Zaffarullah Khan, Messing Up the Past: Evolution of History Textbooks in Pakistan, 1947-2000, Sustainable Development Policy Institute, 2004. For a discussion of the Pakistan militarys role in playing up the Indian threat, see P.R. Chari and Ayesha Siddiqa-Agha, Defense Expenditure in South Asia: India and Pakistan, RCSS Policy Studies 12, Regional Center for Strategic Studies, Colombo 2000. During the Cold War for example, Pakistan and India were members of opposite camps, with Pakistan choosing to become a Western ally and India, while keeping an ofcial non-aligned stance tilting towards the Soviet block. Pakistan signed a Defense Pact with the US in 1954. The Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation was concluded in 1971. Ijaz Nabi and A. Nasim, Trading with the Enemy: A Case for Liberalizing Pakistan-India Trade in S. Lahiri (ed), Regionalism and Globalization: Theory and Practice. (London: Routledge, 2001). Trade Development Authority of Pakistan. < http://www.epb.gov.pk/v1/index.php>; Directorate General of Foreign Trade, India. < http://dgft.delhi.nic.in/>. The gure for Pakistani exports for this year stands out as an anomaly and may well be result of misreported data. Shaheen Ra Khan, Moeed Yusuf, Shahbaz Bokhari, and Shoaib Aziz, Quantifying Informal Trade Between Pakistan and India, The World Bank, 2007. A number of optimistic projections of the quantitative potential of Indo-Pak trade relied heavily on the belief that informal trade was worth a few billion USD. Khan et al., Quantifying Informal Trade, 2005. SAARC Teachers Exempted from Tax, The News International (online version). <http://www. jang.com.pk/thenews/> (accessed on May 5, 2007). The author originally contributed a modied version of the initial discussion in this section to Khan et al., Regional Integration, Trade and Conict, 2007. A statistical exercise similar to the one presented here was conducted by the author for Khan et al., Managing Conict through Trade, 2007. U. Wickramasinghe, How can South Asia turn the new emphasis on IT provisions to their advantage?, South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SAWTEE), 2001; Shahid J. Burki, Prospects of Peace, Stability and Prosperity in South Asia: An Economic Perspective, 2004. N. Mukherjee, Regional Trade, Investment and Economic Cooperation among South Asian Countries, Paper presented at the International Conference on South Asia as a Dynamic Partner: Prospects for the Future, New Delhi, May 25-27, 1992. Jeffrey A. Frankel and Shang-Jin Wei, The New Regionalism in Asia: Impact and Options in The Global Trading System and Developing Asia (Asian Development Bank, Oxford University Press, 1997). Burki, Prospects, 2004. Quoted in Bandara, Jayatilleke S. and Wusheng Yu Jayatilleke S. Bandara and Wusheng Yu, How Desirable is the South Asian Free Trade Area: A Quantitative Assessment, Global Trade Analysis Project, May 30, 2001.

31

Criterion

34