Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In The Marriage of JB and HB: Petitioner's Reply Brief - 10102011

Uploaded by

Daniel WilliamsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In The Marriage of JB and HB: Petitioner's Reply Brief - 10102011

Uploaded by

Daniel WilliamsCopyright:

Available Formats

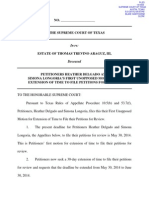

No.

11-0024

I n The S upreme Court of Texas

In the Matter of the Marriage of J.B. and H.B.,

J.B.,

Petitioner,

v.

The State of Texas,

Respondent.

On Petition for Review from the Fifth Court of Appeals at Dallas, Texas

Case No. 05-09-01170-CV

P E TI TI O N E R S R E P LY TO

S TATE S B R I E F O N TH E M E R I TS

James J. Scheske (SBN 17745443)

Jason P. Steed (SBN 24070671)

Akin Gump St r auss Hauer

&Fel d LLP

300 West 6th St., Suite 1900

Austin, Texas 78701

Telephone: (512) 4996200

Facsimile: (512) 4996290

Attorneys for Petitioner J .B.

FILED

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF TEXAS

11 October 10 P5:31

BLAKE. A. HAWTHORNE

CLERK

ii

Ta b le o f C o n te n ts

Index of Authorities .............................................................................................. iii

Argument ................................................................................................................. 1

I. Section 6.204 does not deprive the trial court of jurisdiction

over J.B.s petition for divorce. .................................................................... 1

A. The State misconstrues or ignores this Courts rules of

statutory construction. ..................................................................... 1

B. The State misconstrues the law of standing. ................................. 4

C. The plain text of section 6.204 does not prevent the trial

court from granting J.B.s uncontested divorce. ............................ 7

D. None of the protections the State described are at issue

in this case, and this Court does not decide hypotheticals. ......... 9

II. The States construction of section 6.204 is unconstitutional. ............ 10

A. The State fails to provide a rational basis for denying J.B.

equal access to divorce. .................................................................. 10

B. The State mischaracterizes the right at issue and

effectively admits to depriving J.B. of due process. ..................... 14

C. Baker v. Nelson does not control this case. ................................... 17

D. The State misunderstands the right to travel, which the

State effectively admits to violating. ............................................. 19

E. According to original intent, the Full Faith and Credit

Clause requires the State of Texas to allow J.B. to get a

divorce. ............................................................................................. 21

Prayer..................................................................................................................... 24

Certificate of Service ............................................................................................ 26

Appendix ............................................................................................................... 27

iii

I n d ex o f Au th o ritie s

Page(s)

TEXAS CASES

Aucutt v. Aucutt,

62 S.W.2d 77 (Tex. 1933) ................................................................. 2, 3

Austin Nursing Ctr., Inc. v. Lovato,

171 S.W.3d 845 (Tex. 2005) ................................................................. 4

Brown v. Todd,

53 S.W.3d 297 (Tex. 2001)................................................................... 5

City of DeSoto v. White

288 S.W.3d 389 (Tex. 2009) ................................................................ 1

City of Houston v. Clark,

197 S.W.3d 314 (Tex. 2006) ............................................................... 10

City of Rockwall v. Hughes,

246 S.W.3d 621 (Tex. 2008) ................................................................ 2

Cramer v. Sheppard,

167 S.W.2d 147 (Tex. 1943) .................................................................. 3

Cuneo v. De Cuneo,

24 Tex. Civ. App. 436, 59 S.W. 284 (1900) ........................................ 4

DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Inman,

252 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2008) ........................................................... 4, 9

Dubai Petroleum Co. v. Kazi,

12 S.W.3d 71 (Tex. 2000) ..................................................................... 3

Entergy Gulf States, Inc. v. Summers,

282 S.W.3d 433 (Tex. 2009) ............................................................ 1, 2

Kappus v. Kappus,

284 S.W.3d 831 (Tex. 2009) ................................................................ 2

Mireles v. Mireles,

No. 01-08-00499-CV, 2009 WL 884815 (Tex. App.Houston [1st

Dist.] Apr. 2, 2009, pet. denied) .......................................................... 4

iv

Sullivan v. University Interscholastic League,

616 S.W.2d 170 (Tex. 1981) ........................................................... 11, 13

VanDevender v. Woods,

222 S.W.3d 430 (Tex. 2007) ............................................................. 10

Vinson v. Burgess,

773 S.W.2d 263 (Tex. 1989) ................................................................. 3

Williams v. Texas State Board of Orthotics & Prosthetics,

150 S.W.3d 563 (Tex. 2004) ...................................................... passim

Whitworth v. Bynum,

699 S.W.2d at 197 ................................................................................ 13

FEDERAL CASES

Baker by Thomas v. General Motors Corp.,

522 U.S. 222 (1998) ............................................................................ 23

Baker v. Nelson,

409 U.S. 810 (1972) .................................................................... passim

Boddie v. Connecticut,

401 U.S. 371 (1971) ................................................................... 14, 16, 17

Broderick v. Rosner,

294 U.S. 629 (1935) ............................................................................ 23

Citizens for Equal Protection v. Bruning,

455 F.3d 859 (8th Cir. 2006) .............................................................. 13

Frontiero v. Richardson,

411 U.S. 677 (1973) ...............................................................................14

Gill v. Office of Personnel Management,

699 F. Supp. 2d 374 (D. Mass. 2010) ................................................. 7

Hicks v. Miranda,

422 U.S. 332 (1975) ............................................................................. 19

In re Balas,

449 B.R. 567 (C.D. Cal. 2011) .............................................................. 7

v

J ohnson v. J ohnson,

385 F.3d 503 (5th Cir. 2004) ............................................................. 19

J ohnson v. Robinson,

415 U.S. 361 (1974) .............................................................................. 13

Lawrence,

539 U.S. at 56667 ................................................................... 15, 16, 19

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 (1967) ............................................................................ 14, 16

Mandel v. Bradley,

432 U.S. 173 (1977) (per curiam) ................................................. 15, 18

Mass. Bd. of Ret. v. Murgia,

427 U.S. 307 (1976) (per curiam) .......................................................14

Memorial Hospital v. Maricopa County,

415 U.S. 250 (1974) ............................................................................. 20

Perry v. Schwarzenegger,

704 F. Supp. 2d 921 (N.D. Cal. 2010) ................................................ 11

Reno v. Florez,

507 U.S. 292 (1993) ....................................................................... 14, 16

Romer v. Evans,

517 U.S. 620 (1996) ..................................................................... passim

United States Dept. of Agriculture v. Moreno,

413 U.S. 528 (1973) ........................................................................ 11, 13

Warth v. Seldin,

422 U.S. 490 (1975) .............................................................................. 5

Washington v. Glucksberg,

521 U.S. 702 (1997) .............................................................................. 15

Williams v. North Carolina,

325 U.S. 226 (1945) .............................................................................14

TEXAS STATUTES

Tex. Fam. Code Chapter 6 .......................................................................14

vi

Tex. Fam. Code 6.001 ........................................................................ 6, 7

Tex. Fam. Code 6.002 ............................................................................ 6

Tex. Fam. Code 6.204 .................................................................. passim

Tex. Fam. Code 6.707 ............................................................................ 9

Tex. Govt Code 311.021 ..................................................................... 10

FEDERAL STATUTES

28 U.S.C. 1738C ..................................................................................... 23

TEXAS CONSTITUTI ONAL PROVI SI ONS

Tex. Const . art. I, 32 .......................................................................... 3, 4

Tex. Const . art V, 8 ............................................................................ 2, 3

U.S. CONSTITUTI ONAL PROVI SI ONS

U.S. Const . Amendment XIV, 1 ...........................................................14

U.S. Const . art. IV, 1 ............................................................................. 22

OTHER AUTHORI TIES

James Madison, Debat es on t h e Adopt ion of t h e Feder al

Const it ut ion

503504 (J.B. Lippincott & Co. 1861) (1787) .................................. 22

Let t er of At t or ney Gener al Hol der (Feb. 2011)

http:/ / scr.bi/ gSzr4J ............................................................................. 16

Recor ds of t h e Feder al Convent ion of 1787 Vol.4 Art.4 Sec.1

Doc.4 (Max Farrand ed., Yale University Press 1937), available at

http:/ / bit.ly/ pUdiI2 ............................................................................ 21

No. 11-0024

I n The S upreme Court of Texas

In the Matter of the Marriage of J.B. and H.B.,

J.B.,

Petitioner,

v.

The State of Texas,

Respondent.

On Petition for Review from the Fifth Court of Appeals at Dallas, Texas

Case No. 05-09-01170-CV

P E TI TI O N E R S R E P LY TO

S TATE S B R I E F O N TH E M E R I TS

To Th e Honor abl e Supr eme Cour t of Texas:

Petitioner J.B. submits this reply to States brief on the merits, and

respectfully shows this Court as follows:

1

Arg u m e n t

I . S e ctio n 6 .2 0 4 d o e s n o t d e p rive th e tria l co u rt o f ju risd ictio n o ve r J.B .s

p e titio n fo r d ivo rce .

A. Th e S ta te m isco n stru e s o r ig n o re s th is C o u rts ru le s o f sta tu to ry

co n stru ctio n .

In City of DeSoto v. White, this Court noted its reluctance to conclude

that a provision is jurisdictional, absent clear legislative intent to that effect.

288 S.W.3d 389, 393 (Tex. 2009). The Court began with the presumption

that the Legislature did not intend to make [a statute] jurisdictional; a

presumption overcome only by clear legislative intent to the contrary. Id.

at 394. The Court held the statute at issue was not jurisdictional because,

among other things, it lacked explicit language indicating the statute was

jurisdictional. Id. at 395396.

Despite this, the State cites City of DeSoto to claim statutory

requirements are jurisdictional when the application of statutory-

interpretation principles reveals a clear legislative intent that they be so.

Brief on the Merits of Respondent the State of Texas (States br.) at 11. The

State ignores that City of DeSoto held the statute was not jurisdictionaland

the State points to no case in which this Court has held a statute was

jurisdictional where the statute did not explicitly declare itself to be so.

Moreover, the State ignores the many other statutory-construction cases

cited in J.B.s opening brief, see Petitioners Brief on the Merits (Pet. br.) at

810, that counsel against the States attempt to read a jurisdictional

provision into section 6.204. See, e.g., Entergy Gulf States, Inc. v. Summers,

282 S.W.3d 433, 465 (Tex. 2009) (we should always refrain from rewriting

2

text that lawmakers chose); City of Rockwall v. Hughes, 246 S.W.3d 621,

62526, 632 (Tex. 2008) (a court risks crossing the line between judicial and

legislative powers when it reads language into a statute that the Legislature

did not put there); Williams v. Texas State Board of Orthotics & Prosthetics,

150 S.W.3d 563, 573 (Tex. 2004) (we will not read into an act a provision

that is not there).

The Court presumes the Legislature chose its words carefully. Kappus v.

Kappus, 284 S.W.3d 831, 836 (Tex. 2009). Thus, the Court should focus on

what a statute says and, just as attentively, on what it does not say. Summers,

282 S.W.3d at 465 (Willett, J., concurring). Section 6.204 of the Family

Code does not say trial courts lack jurisdiction to consider a petition for

divorce. The word jurisdiction never appears. Neither does divorce.

Moreover, as previously noted, see Pet. br. at 6, this Court has declared

that, because district courts are clothed by the [Texas] Constitution with

divorce jurisdiction it does not lie within the power of the Legislature to take

such jurisdiction away from them. Aucutt v. Aucutt, 62 S.W.2d 77, 79 (Tex.

1933). The State argues that Aucutts declaration is no longer the case

because the Texas Constitution has been amended; therefore district courts

no longer have express jurisdiction over all cases of divorce. States br. at 16

n.10. The State is wrong.

Article V, section 8 of the Texas Constitution previously consisted of

three paragraphs detailing district court jurisdiction; it was amended in 1985

to state simply: District Court jurisdiction consists of exclusive, appellate,

and original jurisdiction of all actions, proceedings, and remedies, except in

3

cases where exclusive, appellate, or original jurisdiction may be conferred by

this Constitution or other law on some other court, tribunal, or

administrative body. Texas Const . art. V, 8 (emphasis added).

Jurisdiction over all actions obviously includes divorce. Thus, district

courts remain clothed by the Constitution with divorce jurisdiction, and

Aucuttwhich has never been overruled or even questionedremains

operative. See also Dubai Petroleum Co. v. Kazi, 12 S.W.3d 71, 75 (Tex. 2000)

(all claims are presumed to fall within the jurisdiction of the district court

unless the Legislature has provided that they must be heard elsewhere).

Pushing harder, the State claims article V, section 8 of the Constitution,

granting district courts jurisdiction over all actions, would have to yield to

article I, section 32, prohibiting same-sex marriages. States br. at 16 n.10.

Again, the State is wrong. As in statutory construction, the Court presumes

the language in constitutional provisions was carefully selected, and the

words are interpreted as the people generally underst[an]d them. Cramer v.

Sheppard, 167 S.W.2d 147, 153 (Tex. 1943). Moreover, the Constitution must

be read as a whole and effect must be given to each part of each clause.

Vinson v. Burgess, 773 S.W.2d 263, 265 (Tex. 1989) (internal quotations

omitted). Article V, section 8 gives district courts jurisdiction over all divorce

actions, and article I, section 32 says nothing about jurisdiction or divorce.

The State ignores the plain language, suggests these provisions are in conflict,

then insists section 8 should yield. But this would fail to give full effect to

section 8s provision of jurisdiction over all actions. The better readingthat

follows the text and adheres to this Courts precedent regarding

4

constitutional interpretationis that these two sections are not in conflict

because section 32 says nothing about divorce or jurisdiction.

1

B . Th e S ta te m isco n stru e s th e la w o f sta n d in g .

Standing exists where a party has a justiciable interest in the outcome

of the lawsuit. Austin Nursing Ctr., Inc. v. Lovato, 171 S.W.3d 845, 849 (Tex.

2005). Standing focuses on the party seeking to get his complaint before the

courtnot on the issues he wishes to have adjudicated. DaimlerChrysler

Corp. v. Inman, 252 S.W.3d 299, 308 (Tex. 2008) (Jefferson, C.J.,

dissenting) (quoting Simon v. E. Ky. Welfare Rights Org., 426 U.S. 26, 38

(1976)). And a petitioner does not lack standing simply because he cannot

prevail on the merits of his claim. Id. at 305. For over a century, to

successfully plead an action for divorce and thereby invoke the trial courts

jurisdiction, a petitioner has needed only to allege the existence of a valid

marriageand the allegation alone has been sufficient. Cuneo v. De Cuneo,

24 Tex. Civ. App. 436, 59 S.W. 284 (1900). The petitioners allegations are

1

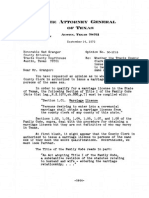

The State has also relied repeatedly on Mireles v. Mireles, No. 01-08-00499-CV, 2009

WL 884815 (Tex. App.Houston [1st Dist.] Apr. 2, 2009, pet. denied), for the

proposition that district courts lack jurisdiction over a divorce involving a same-sex

couple. See, e.g., States br. at 4. But Mireles involved a Texas marriage, where both

parties agreed the marriage was void. 2009 WL 884815, at *2. Here, the issue is

whether a same-sex couple legally married in another state can obtain a divorce in

Texas; therefore, Mireles is inapposite. The place of celebration for the Mireles marriage

is a matter of public recordyet both the State and the court of appeals have ignored

this distinguishing fact. See Op. at 666. A copy of the Mireles marriage certificate is

available at Archives.com: http:/ / bit.ly/ oEB6OC (subscription required). And a

printout from that website, showing the marriage occurred in Brazos County, Texas, is

attached at Tab 1.

5

taken as true and construed in favor of the petitioner. Brown v. Todd, 53

S.W.3d 297, 305 n.3 (Tex. 2001); Warth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490, 501 (1975).

Here, J.B. sought a divorce. 1 CR 56. He indisputably has a justiciable

interest in the outcome of his action. He alleged a valid marriage, that

allegation is taken as true and construed in his favor, and nothing more is

needed. The State cannot point to any caseeven one involving a void

marriagewherein a party to the alleged marriage was held to lack standing

to bring the action to dissolve that marriage.

The State admits that a dispute over the validity of the marriage goes to

the merits of a divorce claim, not to the courts jurisdiction. States br. at 16

17. The State further admits the allegation of a valid marriage is sufficient to

establish standing and jurisdiction. Id. at 17. And further still, the State

admits J.B. alleged he was legally married. Id.

Yet, against its own admissions, the State goes on to argue J.B. lacks

standing because his marriage was not actually valid. In the same paragraph,

the State first admits the validity of the marriage is a question on the merits

and not a matter of standing or jurisdictionthen claims the court should

determine the marriages validity from the face of the petition as a matter of

standing and jurisdiction.

2

2

As previously explained, see Pet. br. at 1415, the States and the court of appeals

construction of section 6.204 will place great strain on the already overburdened trial

courts by requiring them to determine the validity of the alleged marriage in

uncontested divorce actions. Conceding this, the State argues that its position is simply

that where the petition itself demonstrates a lack of standing, the case should be

dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. State br. at 18 (emphasis in original). But the

pleading requirements are minimal, and do not require the identification of the gender

of the parties. See Tex. Fam. Code 6.402. Unless the State proposes that trial courts

Id. Instead of taking J.B.s allegation of a valid

6

Massachusetts marriage as truewhich it isand construing it in J.B.s favor

as required, the State equates it to an allegation that no valid marriage

exists. Id. According to the State, the presentation of a Massachusetts

marriage licensewhich again should be taken as true and construed in J .B.s

favorinstead, makes it clear J.B. is not a party to a marriage.

3

These somersaults of illogic are spawned by the States contention that

only a party to a marriage may sue for divorce, which the State derives from

section 6.001 of the Family Code. See id. But this is a gross misconstrual of

the law. Section 6.001 is titled Insupportability, and is just one of several

sections laying out the grounds for a divorce. (Section 6.002 is for Cruelty,

section 6.003 is for Adultery, etc.) The actual text states: On the petition

of either party to a marriage, the court may grant a divorce without regard to

fault if the marriage has become insupportable because of discord or conflict

Id. at 18.

dismiss only the petitions they catch, inquiry beyond the face of the petition will be the

norm, not the exception.

The State says this is not a problem because no lawyer with any ethical standards

would hide the identity of their clients gender. States br. at 19. But this ignores the fact

that many of the thousands of uncontested divorces filed yearly in Texas do not involve

lawyers, and often one of the parties does not even get involved (as in this case). Thus,

the States and the court of appeals construction of section 6.204 will place a burden on

the courts to police their uncontested divorce dockets.

3

These contortions might have had some merit if J.B. was alleging a valid same-sex

marriage that was entered into in Texas. In that case, it might be possible to say the

allegation of a valid marriage was, on its face, actually the admission of an invalid

marriage. The State has admitted that J.B.s marriage was legally valid under

Massachusetts law. This makes it ridiculous for the State to contend the allegation of

validity was actually an allegation of invalidityparticularly when the allegation must

be construed in J.B.s favor.

7

of personalities . Tex. Fam. Code 6.001. In short, section 6.001 has

nothing to do with requirements for standing.

C . Th e p la in te xt o f se ctio n 6 .2 0 4 d o e s n o t p re ve n t th e tria l co u rt fro m

gra n tin g J.B .s u n co n te ste d d ivo rce .

The State and the court of appeals say the trial court cannot entertain a

petition for divorce without violating section 6.204but in doing so they

fudge the statutes language, reading it as precluding the court from giving

any effect whatsoever to a same-sex marriage. Op. at 666 (emphasis in

original); States br. at 14. This very carefully worded statute, see States br.

at 9 n.5, says no such thing.

4

Section 6.204(c)(1) says the court cannot give effect to a public act,

record, or judicial proceeding that creates, recognizes, or validates a same-

sex marriage. Tex. Fam. Code 6.204(c)(1). A petition for divorce is not a

public act, record, or judicial proceeding and it does not create, recognize,

or validate a same-sex marriageit merely alleges a valid marriage. Thus,

the court does not violate section 6.204 by hearing a petition for divorce.

Section 6.204(c)(2) says the court cannot give effect to a right or

claim to any legal protection, benefit, or responsibility asserted as a result of a

[same-sex] marriage. Tex. Fam. Code 6.204(c)(2) (emphasis added).

4

The State also declares same-sex marriages are legal nullities in this state. States br.

at 8. This exaggerates the scope and reach of section 6.204. A same-sex marriage legally

entered into in another state is still recognized as valid by those states that recognize

same-sex marriageand also by federal law, for some purposes. See In re Balas, 449

B.R. 567 (C.D. Cal. 2011) (DOMA cannot prevent legally-married same-sex couple from

filing joint Chapter 13 petition in bankruptcy); Gill v. Office of Personnel Management,

699 F. Supp. 2d 374 (D. Mass. 2010) (DOMA cannot prevent legally-married same-sex

couple from equal access to federal marriage-based benefits).

8

This provision does not preclude the court from giving effect to any or every

right that might possibly be asserted; rather, it precludes the court only from

giving effect to a right or claim to somethingspecifically, to any legal

protection, benefit, or responsibility. Thus, if the thing to which J.B. is

laying claim is not a legal protection, benefit, or responsibility, then the

plain text of section 6.204(c)(2) is silent about the courts ability to give

effect to that claim. The mere declaration of a divorcethe simple decree,

Divorce granteddoes not constitute a protection or a benefit or a

responsibility. Thus, section 6.204 is silent regarding J.B.s right to a simple

divorce decree.

Finally, the court does not validate an alleged marriage by granting an

uncontested divorce. The State admits the validity of the marriage is a

question on the merits. States br. at 1617. In this uncontested divorce there

is no dispute on the merits and thus no question to be decided by the court.

Like any other undisputed allegation, in any other action, the alleged validity

of the marriage is merely taken as true for the sole purpose of signing the

agreed judgment. The court simply allows two parties the autonomy to settle

their disputes and agree to a judgment. This harms no oneand affects no

one but the parties bound by the judgment.

For the above reasons, the States contention that Texas law prevents the

trial court from hearing and granting J.B.s uncontested petition for divorce is

without merit.

9

D . N o n e o f th e p ro te ctio n s th e S ta te d e scrib e d a re a t issu e in th is

ca se , a n d th is C o u rt d o e s n o t d e cid e h yp o th e tica ls.

The State argues that the only way to adhere to section 6.204s

prohibition against giving effect to a same-sex marriage is to read the

statute as depriving the trial court of jurisdiction over the divorce petition,

because just by filing a divorce petition the petitioner triggers procedural

and substantive protections that, if provided, would be in violation of

section 6.204(c)(2). States br. at 1113. These protections include, for

example, the protection against being subjected to a debt incurred by ones

spouse and the limitation on ones spouses ability to transfer property, during

the pendency of the divorce. Tex. Fam. Code 6.707.

These miscellaneous protections are red herrings. This is an

uncontested divorcemeaning there are no disputes. The protections the

State mentions arise only where there is a dispute between the partiesover,

for example, the incurrence of a debt or the transfer of property. Neither J.B.

nor H.B. is claiming (or challenging the claim to) any protection listed by

the State. Thus, the question whether the trial court could give effect to

that claim is not before this Courtand this Court does not decide

hypotheticals. Inman, 252 S.W.3d at 304. The only question is whether

section 6.204 prevents the trial court from hearing and granting J.B. and

H.B.s uncontested petition for divorce.

For the above reasons, and for the reasons provided in J.B.s initial brief,

the Court should reject the States construction of section 6.204 as

jurisdictional, should reverse the court of appeals decision, and should

remand to the trial court for the determination of J.B.s petition for divorce.

10

I I . Th e S ta te s co n stru ctio n o f se ctio n 6 .2 0 4 is u n co n stitu tio n a l.

In addition to ignoring the rules of statutory construction noted above,

the State also ignores the rule that says this Court, [w]hen faced with

multiple constructions of a statute, must interpret the statutory language

in a manner that renders it constitutional if it is possible to do so, and should

avoid a construction that renders the statute constitutionally suspect. City

of Houston v. Clark, 197 S.W.3d 314, 320 (Tex. 2006); Williams, 150 S.W.3d

at 571 (We must, if possible, construe statutes to avoid constitutional

infirmities.); see also VanDevender v. Woods, 222 S.W.3d 430, 432433

(Tex. 2007) ([j]udicial restraint cautions that when a case may be decided on

a non-constitutional ground, [the Court] should rest [its] decision on that

ground and not wade into ancillary constitutional questions.); Tex. Govt

Code 311.021 (Court presumes a statute is intended to comply with the

U.S. Constitution).

A. Th e S ta te fa ils to p ro vid e a ra tio n a l b a sis fo r d e n yin g J.B . e q u a l

a cce ss to d ivo rce .

Under federal Equal Protection jurisprudence, a law is constitutionally

suspect if it singles out gays and lesbians for disfavored treatment. Romer v.

Evans, 517 U.S. 620, 631 (1996). The State claims it does not single out gays

and lesbians for disfavored treatment, but instead singles out validly

married unions of one man and one woman for favored treatment. States

br. at 31. This sort of chicanery merely reframes the disparate treatment

like the segregationist who claims Jim Crow does not disfavor blacks, it

merely favors whites. The State candidly concedes that disparate treatment

exists. States br. at 24, 31. The question is not whether the disparate

11

treatment can be framed as favorable to one group rather than disfavorable

to another; the question is whether the State can provide a rational basis to

justify the disparate treatment.

Even under the most deferential standard of review, the court must

insist on knowing the relation between the classification adopted and the

object to be obtained. Perry v. Schwarzenegger, 704 F. Supp. 2d 921, 995

(N.D. Cal. 2010) (citing Romer, 517 U.S. at 631) (internal quotations

omitted). To survive rational basis review, a law must do more than

disadvantage or otherwise harm a particular groupit must rationally

further some legitimate government interest. United States Dept. of

Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U.S. 528, 534 (1973). This demand for a rational

basis, while deferential, is meant to ensure that classifications are not drawn

for the purpose of disadvantaging the group burdened by the law. Romer,

517 U.S. at 633.

Here, section 6.204 of the Family Code enacts a classification scheme

based on sexual orientation; the group burdened by the law is gays and

lesbians. Cf. Romer, 517 U.S. at 633. And the burden, under the States

construction of the statute, is that same-sex couples legally married in

another state are denied the right to divorce that is provided to opposite-sex

couples similarly situated. The State fails to provide a rational basis for this

unequal treatment. In other words, the State fails to explain how denying

J.B. access to divorce rationally further[s] some legitimate government

interest. Cf. Moreno, 413 U.S. at 534; see also Sullivan v. University

Interscholastic League, 616 S.W.2d 170, 172173 (Tex. 1981) (holding statute

12

treating two classes of students unequally was unconstitutional because

disfavorable treatment of one class did not operate rationally to further the

states interest; the states legitimate goal did not justify the harsh means of

accomplishing this goal utilized by the [statute]).

The importance of the distinction between the right to marry and the

right to divorce cannot be overstated. The State insists it has a legitimate

interest in promoting the procreative relationship, which justifies

restricting marriage to opposite-sex couplesand that this is the purpose of

section 6.204. States br. at 30. But no matter how vociferously Texas

opposes same-sex marriage, it cannot prevent J.B. and H.B. from getting

marriedbecause they already did. Even if the State can show that

classifying persons based on sexual orientation and denying same-sex couples

the right to marry furthers the States interest in promoting the procreative

relationship, this rationale is unavailing here because J.B. is not seeking to

get married. If the State wants to construe section 6.204 as also denying J.B.

the right to divorce, it must show how this additional, distinguishable

operation of the law rationally furthers the States interest.

Both the court of appeals and the State have failed to do this.

5

5

The court of appeals only discussed a rational basis for disallowing same-sex marriage

and did not distinguish between marriage and divorce. See Op. at 677678.

The State

defines its interest as the promotion of stable family environments for

procreation and the rearing of children by a mother and a father. States br.

at 29, 31. But the State fails to show how treating J.B. unequally, by denying

him the right to divorce, operates rationally to further this interest.

13

Cf. Sullivan, 616 S.W.2d at 172173. In other words, the State fails to show

its construction of section 6.204 does more than disadvantage legally-

married same-sex couples. Cf. Romer, 517 U.S. at 633.

Instead of attempting to satisfy this standard, the State relies primarily

on a court of appeals decision from Indiana to turn the standard inside-out

arguing that, because providing divorce to J.B. does not further the States

interest, the State does not have to provide that divorce. States br. at 31

(citing Morrison v. Sadler, 821 N.E. 2d 15, 35 (Ind. Ct. App. 2005)). This is

wrong. Under rational-basis review, Equal Protection still requires equal

treatment as a baselinebut unequal treatment can be justifiable if it

reasonably furthers the States legitimate interests. See Whitworth v. Bynum,

699 S.W.2d 194, 197 (Tex. 1985) (citing Sullivan, 616 S.W.2d at 172); Romer,

517 U.S. at 633; Moreno, 413 U.S. at 534. The States contention that it does

not have to provide equal treatment unless that equal treatment furthers its

interests should be rejected out of hand.

6

Because the State cannot provide a rational basis for denying same-sex

couples legally married in another state equal access to divorce, its

construction of section 6.204 is unconstitutional.

7

6

Morrison involved an Indiana statutes constitutionality under the Indiana Constitution.

821 N.E. 2d at 35. Indiana constitutional law is irrelevant here. The State also cites

Citizens for Equal Protection v. Bruning, 455 F.3d 859, 868 (8th Cir. 2006), and

J ohnson v. Robinson, 415 U.S. 361, 383 (1974)but those cases both held the unequal

treatment at issue rationally furthered the governments interest. Neither case supports

the States inverted proposition that it does not have to provide equal treatment unless it

furthers the States interest.

7

The State fails to survive rational-basis scrutiny, but strict scrutiny should apply. See

Pet. br. at 2933. The States only argument against strict scrutiny is that gays and

lesbians are not a suspect class because they are not politically powerless. States br.

14

B . Th e S ta te m isch a ra cte rize s th e righ t a t issu e a n d e ffe ctive ly a d m its

to d e p rivin g J.B . o f d u e p ro ce ss.

The Due Process Clause says: No State shall deprive any person of

life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. U.S. Const . Amend.

XIV, 1. The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized both a substantive right

under Due Process, e.g., Reno v. Florez, 507 U.S. 292, 301302 (1993) (state

law cannot interfere with fundamental liberty interests unless it survives

strict scrutiny), and a procedural right under Due Process. E.g., Boddie,

401 U.S. at 379380 (state must provide a meaningful opportunity to be

heard before depriving individual of life, liberty, or property). The States

construction of section 6.204 violates both.

The Supreme Court has recognized the right to divorce as distinct from

the right to marry. See Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 383 (1971)

(divorce is an adjustment of a fundamental human relationship); Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 12 (1967) (infringements on the freedom to marry or

not to marry are subject to strict controls (emphasis added)); Williams v.

North Carolina, 325 U.S. 226, 230 (1945) (divorce affects personal rights of

the deepest significance).

8

at 28. But a class is also suspect if it includes individuals who possess an immutable

characteristic determined solely by the accident of birth, Frontiero v. Richardson, 411

U.S. 677, 688 (1973), or persons who have been subjected to a history of purposeful

unequal treatment. Mass. Bd. of Ret. v. Murgia, 427 U.S. 307, 313 (1976) (per curiam).

The State offers no response to the fact that gays and lesbians fit both of these

descriptions. Moreover, the State never addresses the fact that its construction of

section 6.204 treats same-sex marriages disfavorably even compared to marriages made

void under Chapter 6 of the Family Code. See Pet. br. at 2223.

8

The State claims Baker v. Nelson limits the effect of Boddie, Loving, and Williams.

States br. at 32 n.23. But this is wrong. An unexplicated summary affirmance like

Baker is not to be read as a renunciation of doctrines previously announced in

15

The State correctly insists that marriage is a fundamental right, and

repeatedly insists that divorce is part of marriagebut then contends there is

no fundamental right to divorce. See States br. at 3234. Presumably the

State would agree that a legally-married opposite-sex couple has a

fundamental right to divorceso the obvious question is why a legally-

married same-sex couple would not have that same right. To reconcile these

inconsistencies, the State re-characterizes the issue as the right to dissolve a

same-sex marriage by divorce in a state that does not recognize the marriage.

Id. at 34.

The State justifies this myopic characterization by pointing to

Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 720721 (1997). See id. But

Glucksberg merely requires a careful description of the right at issue, and

was concerned with the subtle distinctions between the right to choose a

humane, dignified death, the right to die, and the right to commit suicide.

521 U.S. at 722723. Glucksberg does not support the States approach. To

the contrary, as the Supreme Court made clear in Lawrence, the right at issue

must not be construed too narrowly. Lawrence, 539 U.S. at 56667, 578

(rejecting Bowers characterization of the right at issue as the right of

homosexuals to engage in sodomy, and instead characterizing it as an

individuals right to privacy in sexual conduct).

Here, the Court should reject the States narrow, Bowers-like description

of the right at issue and instead define it as the right of legally married

[Supreme Court] opinions after full argument. Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 176

(1977) (per curiam) (internal quotations omitted).

16

individuals to divorce. And under Loving, Boddie, and Williams, this right

to divorce should be recognized as fundamental.

9

But even if the right to divorce is not fundamental, the States

construction of section 6.204 still violates J.B.s procedural rights under Due

Process. The State cites DOMA to argue it does not have to recognize J.B.s

marriage and therefore does not have to give J.B. access to divorce. States br.

at 33. But as noted previously, see Pet. br. at 21, DOMA has become

constitutionally suspect.

The Court therefore

should hold that the States construction of section 6.204 violates J.B.s

substantive rights under Due Process, for depriving him of his right to

divorce. See Reno, 507 U.S. at 301302; Boddie, 401 U.S. at 382383.

10

Nevertheless, relying on DOMA and on its construction of section

6.204, the State claims it does not owe J.B. any process respecting [his] out-

of-state marriage. States br. at 35 (emphasis added). This proclamation is

an audacious display of the States disregard for J.B.s rights, and is precisely

the sort of State deprivation of individual rights and liberties that the

Fourteenth Amendment was designed to prohibit.

Moreover, the wording of DOMA is almost

identical to the wording of section 6.204meaning like section 6.204 it can,

and therefore should (to avoid constitutional infirmity), be construed as

speaking only to marriage and not to divorce.

9

Alternatively, the Court could rely on Lawrence to recognize the fundamental, individual

right of autonomy in decisions relating to marriage. 539 U.S. at 574. In contrast, the

State can point to no authority for its characterization of the right at issue.

10

See also Letter of Attorney General Holder (Feb. 2011), http:/ / scr.bi/ gSzr4J.

17

The State does not dispute J.B. was legally married in Massachusetts.

And the State cannot dispute that J.B. is asserting a right to divorce based on

that marriage. Due Process requires the State, at minimum, to provide J.B.

with a meaningful opportunity to be heard, before the State deprives him of

his right to divorce. See Boddie, 401 U.S. at 379380.

The State says it provides for voidance proceduresas though this

satisfies its Due Process obligations. See States br. at 35. But the State

misses the point. J.B. is asserting a right to divorce. Denying J.B. access to

the court on his petition for divorce, and forcing him into a voidance

procedure, constitutes the deprivation of J.B.s right to a divorceand this

violates J.B.s procedural rights under Due Process because, according to the

States own admission, it occurs without a hearing (i.e., without a trial on the

merits of J.B.s petition for divorce).

C . Baker v. Nelson d o e s n o t co n tro l th is ca se .

The State argues Baker v. Nelson, 409 U.S. 810 (1972), forecloses any

claim of constitutional entitlement to same-sex divorce. States br. at 2526.

This misconstrues and exaggerates the precedential effect of Baker. Even the

Fifth Court of Appealswhich embraced most of the States arguments

concluded Baker is not controlling because it concerns the recognition of a

same-sex marriage on a going-forward basissomething distinguishable

from the mere granting of a divorce. Op. at 2223.

Baker concerned a petition for certiorari challenging Minnesotas

refusal to issue a marriage license to a same-sex couple. The U.S. Supreme

Court dismissed the petition for lack of a substantial federal question without

18

an opinion. From this cursory dismissal, and without any support in either

the lower court holding or the Supreme Courts summary order, the State

concocts a broad holding that purportedly prevents anyone from challenging

the traditional definition of marriage, including claims for various legal

rights associated with marriage. States br. at 26. Baker cannot bear this

load.

A summary dismissal like Baker has an extremely narrow precedential

effect. It is binding only on the precise issues presented and necessarily

decided by the Court. Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 176 (1977) (per

curiam) (emphasis added). A summary disposition like Baker does not

necessarily affirm a lower courts reasoning. Id. at 175. And it controls only

to the extent that the issues in a future case are the same as those raised

previously. Id. at 174-77. This standard is exacting, and prevents a case like

Baker from having preclusive effect when even extremely minor differences

in the facts are present. See id. at 176 (issues presented were not the same

between an elected officials challenge to an election statute and a previous

election challenge that had been summarily dismissed).

Here, as the court of appeals correctly concluded, Baker has no

precedential effect because the issues resolved in Baker are not the same as

those before this Court. Op. at 671672. J.B. does not seek to be married

he seeks a divorce. And his demand for equality in divorce raises different

constitutional issues, interests, and arguments from those raised in Baker.

Further still, Bakers precedential effect is undermined by the principle

that summary dismissals are binding only to the extent they have not been

19

abrogated by subsequent doctrinal developments in the Supreme Courts

case law. Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332, 344 (1975). Baker came well

before the line of casesexemplified by Romer and Lawrencethat

recognizes an individuals right to be free from unwarranted governmental

intrusion and from disfavorable treatment based on sexual orientation. See

Romer, 517 U.S. at 631; Lawrence, 539 U.S. at 574. After Romer, all laws that

disadvantage gays and lesbians, and single them out for disfavored

treatment, are constitutionally suspect. See J ohnson v. J ohnson, 385 F.3d

503, 532 (5th Cir. 2004). And after Lawrence, personal decisions relating to

marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, [and] child

rearing are protected from unwarranted intrusion by the stateand

[p]ersons in a homosexual relationship may seek autonomy for these

purposes, just as heterosexual persons do. 539 U.S. at 574. In short, Romer

and Lawrence have modified the law from what it was at the time of Baker,

thereby undermining Bakers precedential authority.

Given the above, the court of appeals was correct in concluding Baker

does not control this case.

D . Th e S ta te m isu n d e rsta n d s th e righ t to tra ve l, wh ich th e S ta te

e ffe ctive ly a d m its to vio la tin g.

The State says there is no evidence that Texas laws were enacted with

the goal of discouraging anyone from moving to Texastherefore they do

not violate the right to travel. States br. at 3637. But this is neither the

argument being made nor the standard to be applied. The proper question

is: Does the States construction of section 6.204 operate[] to penalize those

persons who have exercised their constitutional right of interstate

20

migration? Memorial Hospital v. Maricopa County, 415 U.S. 250, 258

(1974). It does, because a same-sex couple legally married in another state

loses their right to divorce if they move to Texas.

The State says treating J.B. and H.B. like other legally married couples

in Texas is just a repackag[ing] of J.B.s Equal Protection claim. States br. at

36. The right to travel indeed overlaps with the right of equal protection

but the State misunderstands the relevant comparisons. The States

construction of section 6.204 violates Equal Protection because it creates a

classification based on sexual orientation to treat similarly situated couples

same-sex couples legally married in another state and opposite-sex couples

legally married in another stateunequally. And the States construction of

section 6.204 violates the right to travel because it treats migrants to Texas

who have a right to a divorce differently from residents of Texas who have a

right to a divorceby depriving the migrants of their right simply because

they moved here.

The State claims its construction of section 6.204 does not violate the

right to travel because it treats J.B. and H.B. just like any other same-sex

couple in Texas. States br. at 36. But this is the wrong comparisonand in

fact, in this declaration the State effectively admits to violating J.B.s right to

travel. J.B. and H.B. indisputably had a right to divorce in Massachusetts,

before moving to Texas. Treating J.B. and H.B., upon their migration to

Texas, like a same-sex couple that never had a claim to divorce, effectively

penalizes J.B. and H.B. for moving to Texaswhich constitutes a violation of

their constitutional right to travel. Cf. Maricopa County, 415 U.S. at 258.

21

Finally, the State argues there is no constitutional right to be treated by

the laws of ones new state of residence just the way one was treated by the

laws of a previous state of residence. States br. at 37. This is trueand no

claim has been made to any such right. Rather, J.B. asserts his constitutional

right not to be penalized for migrating to another state. The State fails to

show its construction of section 6.204 does not penalize J.B. for moving here.

E . Acco rd in g to o rig in a l in te n t, th e Fu ll Fa ith a n d C re d it C la u se

re q u ire s th e S ta te o f Te xa s to a llo w J.B . to ge t a d ivo rce .

There are few U.S. Supreme Court decisions addressing the Full Faith

and Credit Clause. For this reason, it is useful to reexamine the original

intent and actual text of the constitutional provision.

James Madisons early draft read: Full faith shall be given in each State

to the acts of the Legislatures, and to the records and judicial proceedings of

the Courts and Magistrates of every other State.

11

And another version was

proposed: Whensoever the act of any State, whether legislative[,]

executive[,] or judiciary[,] shall be attested and exemplified under the seal

thereof, such attestation and exemplification shall be deemed in other

State[s] as full proof of the existence of that actand its operation shall be

binding in every other State.

12

11

Th e Recor ds of t h e Feder al Convent ion of 1787 Vol.4 Art.4 Sec.1 Doc.4 (Max

Farrand ed., Yale University Press 1937), available at

From this it is clear: the Full Faith and

Credit Clause was originally quite expansive in its requirement that each

state honor the laws and actions of the other states.

http:/ / bit.ly/ pUdiI2.

12

Id.

22

At the Philadelphia Convention, a draft was submitted based on

Madisons version, which read: Full faith and credit ought to be given in

each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings, of every other

state; and the legislature shall, by general laws, prescribe the manner in

which such acts, records, and proceedings, shall be proved, and the effect

which judgments, obtained in one state, shall have in another.

13

Gouverneur Morris proposed amending this draft, to replace all the

wording after effect with thereof.

14

The concern was expressed that this

might authorize Congress to modify the effect of legislative actsand

support for Morriss amendment was offered only with the understanding

that Congresss power was limited to prescribing the effect of judgments.

15

The provision was further amended to change ought to to shall, in

the first clausemaking full faith and credit mandatory; and shall was

replaced with may in the second clausemaking Congresss ability to

prescribe merely permissive.

In

other words, the Founders intent was still to require each state to give full

faith and credit to the operative effect of the lawsparticularly the

legislationof other states.

16

13

James Madison, Debat es on t h e Adopt ion of t h e Feder al Const it ut ion 503

504 (J.B. Lippincott & Co. 1861) (1787), available at

In other words, the Founders intent was to

require each state to give full faith and credit to the acts of other statesand

http:/ / bit.ly/ pH8R6J.

14

Id.

15

Id.

16

Id.; see U.S. Const . Art. IV, 1.

23

to diminish Congresss ability to alter this obligation.

17

Add to this the axiom that the Constitution cannot be amended by

legislation, and it must be concluded that, under the original intent of the

Founders, DOMAs limitation on a states obligation to give full faith and

credit to a marriage legally created in another state, see 28 U.S.C. 1738C,

should be read narrowly. And because section 6.204 depends on DOMA, it

should be read narrowly too.

This is consistent

with the U.S. Supreme Courts assessment that the animating purpose of the

full faith and credit command was to make [the several states] integral

parts of a single nation throughout which a remedy upon a just obligation

might be demanded as of right, irrespective of the state of its origin. Baker

by Thomas v. General Motors Corp., 522 U.S. 222, 232 (1998).

The State claims that even without DOMA, the judicially-created

public policy exception allows it to consider J.B.s marriage a legal nullity,

and to therefore deny him the right to divorce. States br. at 3940. But the

room left for the play of conflicting policies is a narrow one. Broderick v.

Rosner, 294 U.S. 629, 642 (1935). In particular, a state cannot escape its

constitutional obligations (under the full faith and credit clause) by the

simple device of denying jurisdiction to Courts otherwise competent. Id.

The original intent and plain text of the Full Faith and Credit Clause

suggest Texas shouldat a bare minimumcredit that J.B. and H.B. were

legally married in Massachusetts, and therefore are entitled to a divorce.

17

Specifically, it was understood by those present that Congress was being limited to an

ability to prescribe the effect of judgments. See id.

24

P ra ye r

For the above reasons, for the reasons given in J.B.s initial brief, and in

the interests of reason and justice, J.B. asks this Court to rule section 6.204

does not deprive the trial court of jurisdiction over his petition for divorce

or that Section 6.204 is unconstitutional to the extent it precludes his action

for divorceand to reverse the judgment of the court of appeals and remand

to the trial court for further proceedings. In the alternative, J.B. asks the

Court to remand to the court of appeals to address J.B.s constitutional

challenges. And J.B. respectfully requests any such other and further relief

deemed just and proper.

25

Respectfully submitted,

By: / s/ James J. Scheske

James J. Scheske

State Bar No. 17745443

Jason P. Steed

State Bar No. 24070671

Akin Gump St r auss

Hauer &Fel d LLP

300 W. 6th St., Suite 1900

Austin, Texas 78701

Telephone: 512.499.6200

Facsimile: 512.499.6290

jscheske@akingump.com

jsteed@akingump.com

Attorneys for Petitioner J .B.

26

C e rtifica te o f S ervice

I hereby certify that a true and correct copy of the foregoing Pet it ioners

Reply Brief t o t he St at es Brief on t he Merit s was forwarded to counsel of

record by email and certified mail, return receipt requested, on this 10th day

of October 2011.

James D. Blacklock

Office of the Attorney General

P. O. Box 12548

Austin, Texas 787112548

(512) 9362872 (telephone)

(512) 4742697 (facsimile)

Email: jimmy.blacklock@oag.state.tx.us

H.B.

[ address on file]

/ s/ James J. Scheske

James J. Scheske

27

No. 11-0024

I n The S upreme Court of Texas

In the Matter of the Marriage of J.B. and H.B.,

J.B.,

Petitioner,

v.

The State of Texas,

Respondent.

On Petition for Review from the Fifth Court of Appeals at Dallas, Texas

Case No. 05-09-01170-CV

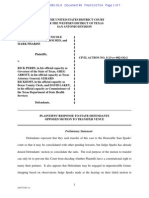

Ap p e n d ix To P etitio n e rs R e p ly

To S ta te s B rie f O n Th e M e rits

Tab 1 Texas Mar r iage Recor d f or Andr ew R. Mir el es and

Jennif er S. Al l en

TAB 1

Members Area - Archives

ARCHIVES

Search All Archives

Vital Records

Mlll!!JJY ReQm.

...!W:'!)

http://www.archives.comimemberlDefault.aspx? _ act=VitaIRecordV ...

Showing Texas Marriage Record for "Andrew R Mireles and Jennifer 5 Allen"

Andrew R Mireles and Jennifer S Allen

First Name:

Middle Name:

Last Name:

Gender:

Birth Date:

Spouse First Name:

Spouse Middle Name:

Spouse Last Name:

Spouse Gender:

Spouse Birth Date:

Marriage Date:

Marriage Location:

Record Type:

Certificate Number:

Collection:

Certificate:

Source Information

Source:

Years:

Description:

Address:

Cemetery Listings

Andrew

R

Mireles

Male

1974

25

Jennifer

S

Allen

Female

1979

20

Feb 23,1999

Brazos, TX M<!p

Marriage Record

022386

Texas Marriage Records

!:'lard Copy

Texas Department of State Health

Services

1966 to 2008

This collection of Texas marriage

records was provided by the Texas

Department of State Health Services.

It contains data from 1966-2008.

PO Box 149347, Austin, Texas

78714-9347

Suggested Records

Find your ancestors in

the

,N1d[<)WMimle in

newspaper articles,

Hard Copy Certificate

Get a hard copy certificate of

this record, We provide acces"

to official government-issued

vital records, including birth,

death, marriage and divorce

records,

This Day in History

February 23", 1999

headlines from

F'!PI]Jilry23,

Census Records

Imfl)jgratio[1...!.,Eassellll.'tLl,ists

Newspapers

Obituaries

Surname Histories

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Crain Ready-Cut House Company Catalouge Part 2Document17 pagesCrain Ready-Cut House Company Catalouge Part 2Daniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 1920 Crain Ready-Cut House Company CatalogDocument53 pages1920 Crain Ready-Cut House Company CatalogDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Goodfriend v. Debeauvoir Court OrderDocument3 pagesGoodfriend v. Debeauvoir Court OrderDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Delgado V Araguz: Supreme Court Grants Motion For ReviewDocument6 pagesDelgado V Araguz: Supreme Court Grants Motion For ReviewDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Delgado V Araguz: Petitioners First Unopposed Motion For Extension of Time To File PetitionsDocument6 pagesDelgado V Araguz: Petitioners First Unopposed Motion For Extension of Time To File PetitionsDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Delgado V Araguz: Response To Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Nikki AraguzDocument88 pagesDelgado V Araguz: Response To Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Nikki AraguzDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Delgado V Araguz: Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Heather DelgadoDocument111 pagesDelgado V Araguz: Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Heather DelgadoDaniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Crawford Martin Opinion 1216Document5 pagesCrawford Martin Opinion 1216Daniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Delgado V Araguz: Reply in Support of Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Heather Delgado, Et Al.Document21 pagesDelgado V Araguz: Reply in Support of Petition For Review Filed On Behalf of Heather Delgado, Et Al.Daniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 14-50196 #14288Document54 pages14-50196 #14288Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 5:13-cv-00982 #73Document48 pages5:13-cv-00982 #73Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- 1:13-cv-00631 #42Document7 pages1:13-cv-00631 #42Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- DeLeon V Perry PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO STATE DEFENDANTS 1-17-2014Document28 pagesDeLeon V Perry PLAINTIFFS' RESPONSE TO STATE DEFENDANTS 1-17-2014Daniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- McNosky V Perry DEFENDANT'S RULE 12 (B) (1) MOTION TO DISMISS 9-16-13Document5 pagesMcNosky V Perry DEFENDANT'S RULE 12 (B) (1) MOTION TO DISMISS 9-16-13Daniel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- 1:13-cv-00631 #24Document16 pages1:13-cv-00631 #24Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- TKD Amended ComplaintDocument214 pagesTKD Amended ComplaintHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Clinton 6Document563 pagesClinton 6MagaNWNo ratings yet

- SPA - SampleDocument2 pagesSPA - SampleAP GeotinaNo ratings yet

- NOTICE by AFF of Relinquisment of Resident Agency Status Howard Griswold 4 14 13Document3 pagesNOTICE by AFF of Relinquisment of Resident Agency Status Howard Griswold 4 14 13Gemini Research100% (1)

- Ibn Khaldun Concept Assabiya - Tool For Understanding Long-Term PoliticsDocument33 pagesIbn Khaldun Concept Assabiya - Tool For Understanding Long-Term PoliticsMh Nurul HudaNo ratings yet

- (Written Work) & Guide: IncludedDocument10 pages(Written Work) & Guide: IncludedhacknaNo ratings yet

- Cults Factions and SyndicatesDocument12 pagesCults Factions and SyndicatesChris HamiltonNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Cagandahan G.R. No. 166676 September 12, 2008Document2 pagesRepublic vs. Cagandahan G.R. No. 166676 September 12, 2008fe rose sindinganNo ratings yet

- What Is Actual BeautyDocument19 pagesWhat Is Actual BeautyshafiNo ratings yet

- Second Serious Case Overview Report Relating To Peter Connelly Dated March 2009Document74 pagesSecond Serious Case Overview Report Relating To Peter Connelly Dated March 2009Beverly TranNo ratings yet

- Nunez Vs Atty RicafortDocument3 pagesNunez Vs Atty Ricafortjilo03No ratings yet

- DLL For PhiloDocument11 pagesDLL For Philosmhilez100% (1)

- Human Factors: (Pear Model)Document14 pagesHuman Factors: (Pear Model)Eckson FernandezNo ratings yet

- Projects Claims and Damages Report - TemplateDocument18 pagesProjects Claims and Damages Report - Templateprmahajan18No ratings yet

- Attract Women - Inside Her (Mind) - Secrets of The Female Psyche To Attract Women, Keep Them Seduced, and Bulletproof Your Relationship (Dating Advice For Men To Attract Women)Document58 pagesAttract Women - Inside Her (Mind) - Secrets of The Female Psyche To Attract Women, Keep Them Seduced, and Bulletproof Your Relationship (Dating Advice For Men To Attract Women)siesmannNo ratings yet

- Omprakash V RadhacharanDocument2 pagesOmprakash V RadhacharanajkNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Reports (2012) 8 S.C.R. 652 (2012) 8 S.C.R. 651Document147 pagesSupreme Court Reports (2012) 8 S.C.R. 652 (2012) 8 S.C.R. 651Sharma SonuNo ratings yet

- ContarctDocument3 pagesContarctJunaid AnwerNo ratings yet

- Abraham Lincoln's Letter To His Son's HeadmasterDocument9 pagesAbraham Lincoln's Letter To His Son's HeadmasterMohiyulIslamNo ratings yet

- Metacognitive Reading ReportDocument2 pagesMetacognitive Reading ReportLlewellyn AspaNo ratings yet

- Pode Não-Europeus Pensar?Document9 pagesPode Não-Europeus Pensar?Luis Thiago Freire DantasNo ratings yet

- The Kingdom Loyalty of MatthewDocument7 pagesThe Kingdom Loyalty of MatthewrealmenministryNo ratings yet

- Engineering Ethics: Electrical Engineering Department UMTDocument34 pagesEngineering Ethics: Electrical Engineering Department UMTFAISAL RAHIMNo ratings yet

- Company Law AssignmentDocument20 pagesCompany Law AssignmentBilal MujadadiNo ratings yet

- Luzviminda Visayan v. NLRC and Fujiyama RestaurantDocument4 pagesLuzviminda Visayan v. NLRC and Fujiyama RestaurantbearzhugNo ratings yet

- Child Labour Class 12Document16 pagesChild Labour Class 12Garvdeep28No ratings yet

- Debating: 1. To Order A Sequence of ArgumentsDocument5 pagesDebating: 1. To Order A Sequence of ArgumentspabloNo ratings yet

- State of The Nation Address 2019Document2 pagesState of The Nation Address 2019Joy P. PleteNo ratings yet

- Goldenberg CaseDocument3 pagesGoldenberg CaseFriendship GoalNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Staffing: Chapter One Staffing Models and StrategyDocument32 pagesThe Nature of Staffing: Chapter One Staffing Models and StrategyHasib AhsanNo ratings yet