Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stern JSJ 039 03 423 2008

Uploaded by

omnisanctus_newOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stern JSJ 039 03 423 2008

Uploaded by

omnisanctus_newCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

www.brill.nl/jsj

Limitations of Jewish as a Label in Roman North Africa*

Karen Stern

kbstern@gmail.com

Abstract Selective attentions to normative Jewish archaeological materials and exclusions of ambiguous or complex evidence from Jewish archaeological corpora have diverted attention from those artifacts, which might otherwise have yielded more productive observations about the cultural ranges of ancient Jewish populations. Application of more critical approaches to the classication of archaeological evidence, contextual approaches for the analysis of archaeological materials, and the replacement of essentialistic or syncretistic cultural models for Jews with more realistic ones, yield vastly improved understandings of ancient Jewish archaeological materials, and, by extension, better articulated pictures of the continua between early Jewish and Christian cultural identities. Keywords Cultural identity, identity, Jewish archaeology, Jewish art, Jewish Christian relations, North Africa, syncretism, hybridity, rabbinic Judaism, essentialist, archaeology and identity, Roman North Africa, Augustine, epigraphy, indexicality

In the Roman Provinces Gallery at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, a displayed collection of red slip bowls exemplies the ne craftsmanship for which North African pottery workers were renowned, and copied, throughout the ancient Mediterranean.1 The decoration on one of these bowls

*) I gratefully acknowledge the support of the Scholion Center for Interdisciplinary Jewish Studies of the Mandel Institute at Hebrew University, whose grant facilitated my completion of this article. I also would like to thank Ehud Benor and Christine Thompson for their valuable suggestions and feedback. Any errors therein, of course, remain my own. 1) Few of these artifacts possesses secure provenance. Over the centuries, North African sigillata lamps and bowls have accrued on the art market throughout Europe; dubious

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2008 DOI: 10.1163/157006308X294582

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 1

4/17/08 7:23:44 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

depicts a popular motif in fourth and fth-century Christian art from North Africa and Romethe sacrice of Isaac.2 On the bowls surface, Abraham is poised to sacrice his son, Isaac: Abrahams right hand grasps a dagger, while his left hand pushes Isaacs face onto the surface of a burning altar. Isaacs arms are tied behind his back. A divine hand descends from above, while accompanying images of a ram and a tree foretell the storys happier conclusion. The broad design of the piece is typical of the neighboring bowls of comparable period and origin, which depict Orphic scenes or collections of Christian symbols in relief, arranged around the edge of a bowl in a circular formation; Abraham and Isaac, the tree, and the ram, are xed evenly around this bowls tondo. What is the cultural provenance of this artifact? Curators label it as Christian, partly because of its similarity to identied Christian works from North Africa. The bowl is assumed to be one of the many objects Christians dedicated as funerary goods, or donated as votive implements to the basilicas and churches of Africa.3 Its imagery, after all, appropriately demonstrates symbols and sentiments expounded by early church fathers: the grimacing visage of Abraham and the bent back of Isaac express the pathos within the biblical story, epitomize Abrahams supreme piety, and arm Gods ultimate salvation of Isaac. But are curators entirely justied in their classication of the bowl as Christian, in the absence of a clear and documented nd- context for it? Jews, after all, as well as Christians, emphasized the importance of this biblical story in late antiquity.4 Is there a chance that such an artifact, could have been commissioned, owned, or dedicated, by a Jew?5

methods of objects sales and acquisitions have rendered impossible the exact identication of works origins. Though many of these bowls probably originated in North Africa, such pieces were frequently traded throughout the region and were so esteemed that their styles were emulated by artisans elsewhere. For related discussion, see David J. Mattingly and R. Bruce Hitchner, Roman Africa: An Archaeological Review, JRS 85 (1995): 165-213 (201). 2) The bowl is shallow, measures approximately 23 cm in diameter and is composed of ne reddish clay. Its appearance and size resemble those of similar bowls on display. 3) Similar objects are identied as grave goods within Christian North African tombs, though this genre of artifact was frequently exported throughout the Mediterranean; see Mattingly and Hitchner, Roman Africa, 198, 201; J.M. Hayes, Late Roman Pottery (London: British School of Rome, 1972); and idem, A Supplement to Late Roman Pottery (London: British School of Rome, 1980). 4) Rachel Hachlili, Ancient Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 246. 5) Prejudices based on both foreign analogy and rabbinic prohibition of images have shaped scholars expectations about what a Jewish artifact should look like and have informed the

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 2

4/17/08 7:23:44 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

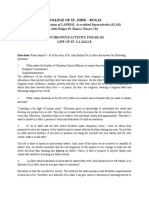

Figure 1. African red slipware bowl depicting the sacrice of Isaac (Boston 1989.690) 2007, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

typologies of such artifacts. These assumptions and the labels they generate bear distinct consequences; analysis of archaeological materials conforms to such classications and ultimately reinforces previous assumptions about North African Roman, Christian, and Jewish artifacts and the cultural practices of those who produced them. Extensive discussions of the problems associated with identifying Jewish artifacts within Ross Kraemer, Jewish Tuna or Christian Fish: Identifying Religious Aliation in Epigraphic Sources, HTR 84 (1991): 141-62. Criteria for determining Jewishness of inscriptions is reviewed within Pieter W. van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs: An Introductory Survey of a Millennium of Jewish Funerary Epigraphy (300 BCE-700 CE) (Kampen: Pharos, 1991).

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 3

4/17/08 7:23:45 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

According to the criteria of art historians, it is nearly impossible to tell. In late ancient literary exegesis and visual art, both Jewish and Christian groups emphasized the story of the Sacrice of Isaac.6 Yet historians of Christian art generally indicate that, until a later period, Christian Sacrice of Isaac scenes rarely depict Isaac as already on top of the altarusually the image of a burning altar occupies a separate space in the design. In this Boston image, Isaac is positioned directly on top of the altar. This distinct feature of the artifact accords with art historians guidelines for Jewish versions of the image in earlier periods, although its dating to the fourth or fth century renders its cultural classication indeterminate.7 Creators of this bowl could have provided a denitive symbol such as a cross, a Chi Rho, or a menorah, to demonstrate an authoritative cultural context for the object. This provision, however, was deemed neither necessary nor desirable.8 To the modern eye, therefore, the bowl appears to be culturally ambiguous. This apparent cultural ambiguity, furthermore, is more common than art historians and taxonomists might like: it manifests itself in many other genres of North African third, fourth, and fth-century art. Countless objectssuch as funerary tiles, bowls, and lamps, which depict biblical scenes and gures, such as Jonah, Adam and Evell modern museums in Tunisia and Algeria.9 These artifacts, too, exhibit distinctly

Hachlili, Ancient Art, 244; Robin Jensen, Understanding Early Christian Art (London: Routledge, 2000), 72. 7) Cf. Hachlili, Ancient Art, 239-46, gs. V-3, V-5, V-6. 8) The possible reasons for this are manifold. Perhaps, the context of an inscription or artifact may have rendered it redundant to provide a clearer marker of cultural dierentiation, or the creator of the object wished for it to be purchasable to a broader group of people. Alternatively, a person who commissioned or designed such a bowl may not have felt it necessary to make such symbolic distinctions. After all, articulations of individual or group identity might not have been so important within certain North African contexts. 9) Certain funerary tiles in the Hadrumentum region depicted the face of Christ, but gurative iconography derived from Christian scriptures is surprisingly rare in African Christian art. For a survey, see Paul Gauckler, Catalogue du Muse Alaoui (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1928). During these periods throughout the Mediterranean, Christian art frequently favored motifs from Hebrew Scriptures in both votive and funerary contexts, on sarcophagi, terracotta funerary tiles, and in mosaic. In North Africa, scenes of Jonah, Daniel, Adam and Eve, and the sacrice of Isaac were most commonly depicted, as detailed in Jensen, Understanding Christian Art, 25. Jensen usefully discusses the complex relationships that develop between popular pagan and Christian genres of art: Compare, for example, the shing scenes and sea life depicted on North African mosaics of the third, fourth and fth centuries C.E. with the fourth-century mosaic oor at Aquileia, demonstrating

6)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 4

4/17/08 7:23:46 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

indeterminate qualities; rarely do words or symbols explicitly mark the images as either Christian or Jewish.10

Methodology, Identity, and the Interpretation of Archaeological Evidence for Jewish Culture of Roman North Africa of the Second to Sixth Centuries C.E. Upon closer inspection, many apparently Christian, or, Jewish artifacts, like the Boston bowl, similarly resist the classications previously assigned to them, and, once reevaluated, prompt dierent lines of general inquiry and analysis.11 For example, should we presume, until proven otherwise, that ancient works of gurative biblical art that possess no explicitly Jewish markers should necessarily be labeled as Christian?12 Can words used in an epitaph simultaneously emulate Christian and Jewish notions about an afterlife? Must a symbol be either a menorah or a cross, or can it be both? Regnant theory about Jewish life in Roman North Africa suers terminally from failure to ask questions such as these. A brief survey of selected North African artifacts demonstrates the need for a dierent approach to Jewish and Christian materials from antiquity, which, unlike conventional methods, can account for greater complexities within North African archaeology and culture.

how the Christian Jonah cycle generally belongs to this category of maritime art. Christian iconography, apparently, made use of these popular motifs and adapted them to its own uses, imbuing them with a somewhat dierent meaning (ibid., 48). 10) When un-provenanced artifacts, such as this Boston bowl, bear gurative images, historians conventionally label them as Christian. After all, scholars continue to assume that Jews abhor gurative representation on artifacts, despite vast and increasing bodies of evidence and scholarship that demonstrate an opposite tendency. See Steven Fine, Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World. Toward a New Jewish Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 47. This objects lack of a denitive cultural marker is worth evaluating in its own regard. 11) Many of these designations are based on curatorial decisions, which are rarely explained in publication. 12) Scholars tend to avoid labeling ambiguous gurative art as Jewish, partly due to proscriptions within the Hebrew Bible and within rabbinic texts, and partly as the result of skepticism about categories and possibilities of Jewish art, see Fine, Art and Judaism, 1-10. Fine draws particular attention to a passage in the Palestinian Talmud (y. Abod. Zar. 3:3 42d), as preserved in a Geniza fragment, which describes an exceptionally neutral attitude toward the use of images in synagogues and elsewhere (ibid., 98); Fine favors the treatment of J.N. Epstein, Additional Fragments of the Jerushalmi, Tarbiz 3 (1931): 20.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 5

4/17/08 7:23:46 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

Previous studies have applied foreign rabbinic and local Christian literary categories to organize and evaluate African Jewish materials. I respond to the shortcomings of these approaches by advocating a distinct method of analysis, that: emphasizes local archaeological comparanda for the categorization and analysis of Jewish archaeological materials; depends upon realistic and articulated models of culture and identity for the examination of artifacts; and, draws attention to Jewish artifacts complexities and regional variability. The resulting analysis resists denitional limitations and responds to the realities of life and culture in a world where people didnt travel much: Jewish residents of third-century Carthage might have frequently reected upon their relationship to Jews elsewhere, but they necessarily interacted with each other, and their non-Jewish Carthaginian neighbors more frequently than they did with Jews from elsewhere. The archaeological record requires commensurate evaluation. To this point, scholarship has rarely addressed Jewish culture of Roman North Africathe partial state of evidence for African Jews has obscured the potential for research. The polemical writings and laws of contemporaneous Christian authors provide the only local literary evidence for North African Jews, while most Jewish archaeological and epigraphical evidence appears so limited and obscure, that few scholars have attempted to edit or analyze it.13 The unruliness of the archaeological materials, combined with

13) Late Roman legal texts also mention Jews specically in North African contexts. These laws are equally Christian and polemical: they criticize Jewish behaviors and identify them with enemy, non-Orthodox Christians, such as Donatists, heretics, and Arians. It is as dicult to extricate the historicity of these representations of Jews, as it is from the polemical writings of Christian authors. For related discussion, see my forthcoming treatment, and Amnon Linder, The Jews in Roman Imperial Legislation (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1987), no. 63; and also Linder, La loi romaine et les juifs de lAfrique du Nord, in Juifs et judasme en Afrique du Nord dans lantiquit et le Haut Moyen Age. Actes du Colloque International du Centre de Recherches et dtudes Juives et Hbraques et du group de recherches sur lafrique antique 26-27 Septembre 1983 (ed. C. Iancu and J.-M. Lassre; Montpellier: Universit Paul Valry, 1985), 57-64. Yann Le Bohec has produced an edited collection of North African Jewish inscriptions and an onomasticon which draws from African epigraphic and foreign rabbinic sources, in Inscriptions juives et judasantes de lAfrique romaine, Antiquits Africaines 17 (1981): 165-207, 208-26. Few others have endeavored historical analysis. Exceptions include: H.Z. Hirschberg, A History of the Jews in North Africa (rev. ed; 2 vols.; Leiden: Brill, 1974-1981), vol. I; and Claudia Setzer, Jews, Judaizers and Judaizing Christians in North Africa in Putting Body and Soul Together (ed. Virginia Wiles, Alexandra Brown, and Graydon Snyder; Valley Forge, Pa.: Trinity Press International, 1997), 185-200.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 6

4/17/08 7:23:46 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

scholars dependence on local Christian and foreign rabbinic literary texts for their interpretation, has ultimately yielded such wildly ranging discussions of the topic that some scholars have concluded that progress in the study of North African Jews remains improbable.14 One solution to this apparent problem relates less to the search for new information, but, rather, more to the application of a dierent method to the same archaeological materialsone that is sensitive to the problems of previous studies. In other words, improved understandings of Jewish life in North Africa and elsewhere in the ancient Mediterranean require reformed methods of classication and archaeological inquiry. Selective attentions to normative Jewish materials and exclusions of ambiguous or complex evidence from Jewish archaeological corpora have diverted attention from those artifacts, which might otherwise have yielded more productive observations about the cultural ranges of ancient Jewish populations.15 An improved approach must endeavor to more nuanced understandings of the state of the evidence itself and must liberate that evidence from partial, historical, rabbinic, Christian and legal paradigms that presently, implicitly, and falsely, govern its analysis.16

14) T.D. Barnes discussion of this matter in Tertullian: A Historical and Literary Study (New York: Clarendon, 1971) diers partly from the position taken by Claude Aziza, Tertullien et les Juifs (Paris: Belles Lettres, 1977). Barnes questions the plausibility of reconstructing a history of North African Jews in the second through fth centuries, contra W.H.C. Frend, A Note on Jews and Christians in Third-Century North Africa, JTS 21 (1970): 92-96. 15) Pieter van der Horst aptly identies the methodological problems endemic to the study of Jewish artifacts: It may be clear by now that the matter is far from being simple. A rigorous application of criteria would require us to regard an epitaph only as Jewish when a number of criteria reinforce one another, e.g., Jewish burial place plus Jewish symbols and epithets . . . Such a methodological strictness runs the risk of excluding valuable material the Jewishness of which is not manifest enough. On the other hand, methodological slackness runs the risk of including non-Jewish material that may blur the picture. It is better, for the sake of clarity, to keep on the strict side, without being extremely rigorous. That is to say, application of two or three criteria together is to be much preferred above applying only one, the more so since in late antiquity Judaism, Christianity, and paganism were not always mutually exclusive categories (Ancient Jewish Epitaphs, 18). A dierent view of interpreting inscriptions and archaeology is espoused in Martin Goodman, Jews and Judaism in the Mediterranean Diaspora in the Late-Roman Period: The Limitations of Evidence, Journal of Mediterranean Studies 4 (1994): 208-24. 16) Possibilities that ancient Jewish identities might defy rabbinic or Christian literary description have been discussed by Daniel Boyarin in Border Lines: The Partition of JudaeoChristianity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). Scholars also continue to challenge the dependability of Christian authors descriptions of contemporaneous

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 7

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

Histories of ancient Jewish communities in the diaspora are, at best, challenging to reconstruct. In the absence of literary evidence, scholars necessarily depend upon extant archaeological and epigraphic materials to compile hypothetical histories of non-rabbinic Jewish populations.17 Such endeavors, however, bear their own complications; methods employed to identify Jewish materials, and the frameworks designated for their interpretation, entirely shape the outcome of scholarly analysis. Many have debated, therefore, the most appropriate methods to qualify materials as Jewish: some advocate more stringent means to identify objects as Jewish, whereby multiple markers are required to satisfy responsible Jewish designations. Others have argued that these materials are so obscure that they are dicult, or, impossible, to interpret at all.18 Dierent conceptions of identity and means of artifact interpretation, however, yield distinct possibilities about considerations of Jewish materials and about their responsible use to approach understandings of otherwise unattested ancient Jewish populations. Archaeological analysis ideally responds to the imagined conditions in which artifacts were produced, used, or deposited. Dominant emphases on artifacts exhibitions of pan-Mediterranean Jewish features continue to obfuscate analyses of evidence for ancient diaspora Jews. Intensied examination of the precise historical and cultural contingencies of individual

Jewish populations. See Andrew Jacobs, The Remains of the Jews: The Holy Land and Christian Empire in Late Antiquity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004); Judith Lieu, Image and Reality: The Jews in the World of Christians in the Second Century (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1992); Jack Lightstone, Christian Anti-Judaism and its Judaic Mirror: The Judaic Context of Early Christianity Revised, in Anti-Judaism in Early Christianity. Vol. 2: Separation and Polemic (ed. Stephen J. Wilson; Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 1986): 103-32; Paula Fredriksen, What Parting of the Ways? Jews and Gentiles in the Ancient Mediterranean City, in The Ways that Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (ed. Adam H. Becker and Annette Yoshiko Reed; Tbingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003), 3-17. Most of these studies question the historicity of Christian literary representations of both Jews and Christians. The analysis of Jewish materials requires commensurate reevaluation, though few have incorporated these more complex perspectives on literature into the interpretation of archaeological evidence. 17) See Paul Trebilco, Jewish Communities in Asia Minor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992); Shimon Applebaum, Jews and Greeks in Ancient Cyrene (Leiden: Brill, 1979); Leonard V. Rutgers, The Jews of Late Ancient Rome: Evidence of Cultural Interaction in the Roman Diaspora (Leiden: Brill, 1995). 18) For a thorough evaluation of the former position, see Van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs, 16-18, and for the latter, see Goodman, Jews and Judaism.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 8

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

Jewish populations and altered approaches to ancient identity, yield more comprehensive and nuanced examinations of the artifacts ancient Jewish populations produced. Ethnographic comparanda from modern Jewish populations in Tunisia illustrate the need to more carefully reconsider evidence for ancient, as well as modern, Jewish populations in the region. Jewish populations in Tunis and Djerba are only seven hours apart by automobile.19 Tunisian and Djerban Jews, however, recount dierent community origins, speak dierent languages, and share distinct relationships with their neighbors.20 Most Jews of Tunis speak French to each other, emulate European ideals and dress, and live in urban apartments in the center of town.21 They live and work with Muslim Tunisians. In contrast, Djerban Jews communicate in Judeo-Arabic, dress idiosyncratically, dwell in walled houses like their Muslim neighbors, but live outside of the town center in the traditional Hara.22 Some men work in town, while women remain largely in the Hara. Jewish domestic and devotional spaces in both Tunis and Djerba contain comparable ritual objects that bear similar Jewish symbols. To focus on the similarities between these to derive broader cultural understandings of these populations would clearly be misleadingthis approach would yield distorted understandings of both Tunisian and Djerban Jewish communities. An improved method would attend to the dierences, as well as the similarities, between the material cultures of the groups: it would recognize how communities expressions of appropriate Jewishness in their domestic and devotional spaces dier according to their family

19) While the Jewish populations in Tunis and Djerba have signicantly dwindled since 1967, they still retain these characteristics. These descriptions are also informed by my experience and travels in Tunisia in the summer and autumn of 2003. 20) Djerban Jews particularly maintain an oral tradition that their community dates to the exile of the Israelites after the Babylonian destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 586 B.C.E. See Andr Chouraqui, Histoire des Juifs en Afrique du Nord (Jerusalem: Hachette, 1985), 52. 21) French citizenship was uniformly granted to Tunisian Jews in 1910this was a decision that produced extensive cultural ramications. See discussion in Hirschberg, A History of the Jews, 2:134-35. The Jewish community in Tunis appears to have retained the strongest ties to Jewish communities in Paris; in times of greatest diculty, the Tunis Alliance Isralite appealed directly to the Alliance Isralite Universelle of Paris. See Norman Stillman, The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1979), 411-12. 22) Details how of Djerban Jews traditionally exhibited idiosyncratic approaches to dress and aversions to integrating with Muslim neighbors in Chouraqui, Histoire des Juifs, 159.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 9

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

10

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

traditions, local cultures and contexts. Perceptions of distinct origins, immigration patterns, socio-economic status, languages spoken, and relationships with neighbors, in addition to local cultural experience, inform these dierences. Evaluations of objects from these Jewish communities require equal attention to dierences and consistencies in their demonstrations of Jewish practices and behaviors. Ancient populations require comparable consideration. Jewish groups in North Africa did not necessarily share uniform cultural experiences; during hundreds of years of Roman and Christian rule, various Jews, like others, migrated to North Africa from all regions of the Mediterranean and under diverse socio-economic conditions.23 Roman slave-ships might have carried some Jews from Syria to sell in ports along the Mauretanian coast. Other Jews might have traveled voluntarily from Rome to African port cities, such as Carthage, or Mogador, to conduct trade. The socioeconomic status of the individual immigrants (whether slave, or not), the socio-economic potential of the immigrants family (whether slave, recently freed, or of higher status), and the length of time an individual or his descendants remained in Africa, are all factors that necessarily shaped the features of local Jewish life. The languages spoken and learned (Greek, Latin, or local dialects), the names conferred to children, and the conventions of devotional and funerary activities, all relate to the origins and aspirations of the individual and the customs of the places she most emulated. North African Jews operated within very dierent cultural environments than Jews in Rome, Asia Minor, or elsewhere in the Mediterranean; African Jews mostly wrote in Latin, not Greek, and shared distinct relationships with indigenous, Neo-Punic, Roman African, and Christian neighbors.24 No more should scholars presume a unied paradigm of anal23) J.-M. Lassres work remains the most comprehensive study of the settlement patterns of Roman, indigenous, and allogenic groups in North Africa. See Lassre, Ubique Populus: Peuplement et mouvements de population dans lAfrique romaine de la chute de Carthage la n de la dynastie des Svres (146 a.C.-235 p.C.) (Paris: ditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientique, 1977). 24) This region stretched westward from central Libya to the Atlantic Ocean. Distinct histories of colonialism and conquest in this particular region enforced its political, cultural, and religious dierences from the rest of the Roman Mediterranean. See discussion in Mattingly and Hitchner, Roman Africa; Brian Warmington, Carthage (2d ed.; London: Hale, 1969); J.B. Rives, Religion and Authority in Roman Carthage from Augustus to Constantine (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995); David Mattingly, Tripolitania (London: Batsford, 1995); Peter Brown, Christianity and Local Culture in Late Roman Africa, JRS 58 (1968): 85-95.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 10

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

11

ysis for the artifacts these Jewish populations produced than they ought for objects produced by Djerban, Tunisian, and Parisian Jews in modernity. I reconsider the material record according to these assessments.25 Distinct understandings of culture facilitate this dierent evaluation of ancient Jewish materials. First, I resist concepts of syncretism, and assimilation, whose application falsely dichotomizes culture;26 these reinforce articial notions about the intrinsic separate-ness of cultures and the artifacts they produce.27 I consider as an advantage, rather, a description of culture as vague, expansive, indivisible and inclusive.28 Here: culture is a

The post-Saussurian semiotic approach is useful in the examination of artifacts as matrices of multiple and simultaneous cultural markers, signs, or, indices. Indexicality enables the labeling of these components. For discussion, see Alec McHoul, Semiotic Investigations: Towards an Eective Semiotics (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1996). It is possible, therefore, to use artifacts to explore concordant and conicting expressions of identity, without presuming the perceptions of human agency that underlie modern theories of human interaction; post-modern theory, which underlies the development of this vocabulary, presumes understandings of human agency and reality, which are anachronistic for the review of ancient societies. I use the semiotic vocabulary here as an analytical tool, but not as the ultimate means of artifacts interpretation. 26) To be certain, culture, like religion, is a non-descriptive and imposed category, which is rarely dened and, as such, has become exceedingly unpopular among theorists of religion and anthropology, see Nicholas Dirks (ed.), Colonialism and Culture (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1992). As Tomoko Masuzawa critically argues, the term culture is dangerously capacious, semantically vague and confused, and, nally, taken as a whole, inconsistent, in Masuzawa, Culture, in Critical Terms for Religious Studies (ed. Mark C. Taylor; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 71. The history of the words use is a varied and problematic one and couched in the emergence of specic and historical ideologies, cf. Raymond Williams, Culture and Society 1780-1950 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958). 27) Assimilation and syncretism models ultimately depend upon notions that cultures may be pristine, distinct, and easily divisible. Assimilation assumes that members of one pristine culture A, can become (voluntarily or subconsciously), more like a pristine culture B. Syncretism frequently describes the end-result of this process as a merged AB culture. Neither of these options is particularly helpful in the evaluation of complex societies, whose cultural components are frequently indivisible. Please see discussion within Peter Van Dommelen, Colonial Constructs: Colonialism and Archaeology in the Mediterranean, World Archaeology 28 (1997): 31-49. At a certain level, furthermore, all cultures are assimilated and syncretized in this waytherein the use of these adjectives is essentially meaningless. 28) As Ann Swidler notes, Culture inuences action not by providing the ultimate values toward which action is oriented, but by shaping a repertoire, or a tool kit, of habits, skills, and types from which people construct strategies of action. Here, I replace Swidlers action, with practice. See discussion in Ann Swidler, Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies, American Sociological Review 51 (1986): 273-86 (273).

25)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 11

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

12

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

concept that permits the situation and interpretation of artifacts within a framework of ancient uses and understandings. Just as culture can serve as an integral unity through which individuals relate and acquire understandings that ultimately establish their personal habits and outlook, so too can material culture. Culture, then, serves as an interactive framework through which to compare material manifestations of North African Jewish, Christian, Roman and Neo-Punic practices. It is the permission of cultural uidity and un-boundedness that encourages improved archaeological analysis. Dierent understandings of identity also facilitate this more nuanced examination of artifacts. The possibility remains that on the same day in Hippo in the fourth century, one woman might identify herself as Jew while entering a synagogue, as a Roman of the provinces when participating in Roman legal litigation, and as a Punic-speaker in the marketplace. As Theodore Schatzki describes, methods of identication can be varied, simultaneous, and alternate.29 Semiotic vocabularies furnish useful means to label precisely how objects can simultaneously signify, or, index, these divergent cultural ideals.30 Attention to various cultural indices, in addition to traditional Jewish ones, permits a more careful evaluation of Jewish artifacts and draws attention to their complex relationships with other Jewish and local African populations. Specic related steps assist this interpretation of the material evidence for North African Jewish populations. A rst stage reevaluates previous criteria for the classications of artifactsoverwrought taxonomies have erroneously included and excluded evidence from Jewish corpora. Scholars traditional methods of determining whether an object is appropriately labeled Christian or Jewish, frequently relate to embedded assumptions about the rigidity and exclusivity of religious symbols and corresponding beliefs.31 Distinct presumptions about what ought to be considered Jewish or Christian have shaped inconsistent interpretations of

29) Theodore R. Schatzki, Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 7. 30) McHoul, Semiotic Investigations, 92. 31) Frequently these assumptions remain unarticulated. An excellent discussion of these diculties is provided in Jan Willem van Henten and Alice J. Bij de Vaate, Jewish or NonJewish? Some Remarks on the Identication of Jewish Inscriptions from Asia Minor, BO 53 (1996): 16-28, and Jan Willem van Henten and Luuk Huitink, Inscriptions from Israel: Jewish or non-Jewish Revisited, Bulletin of Judaeo-Greek Studies 32 (2003): 37-46.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 12

4/17/08 7:23:47 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

13

North African culture. Application of more critical approaches to the classication of archaeological evidence, contextual approaches for the analysis of archaeological materials, and the replacement of essentialistic or syncretistic cultural models for Jews and Christians with more realistic ones, yield vastly improved understandings of these ancient Jewish materials, and, by extension, better articulated pictures of the continua between local African, Jewish, and Christian cultures.32 Studies of ancient Jewish populations continue to question what is a Jew in antiquity, while scholarship of Jewish archaeology and epigraphy challenges material evidence with correlative questions,33 such as is it [an object] Jewish? and how does it mark itself as such?34 Such historical and archaeological queries inevitably reinforce scholars emphases on features of artifacts that appear to be most Jewish to them; they generally ignore or disqualify artifacts multiple features that ambiguously index Jewish populations, or index multiple cultural references equally and simultaneously. Inevitably, scholars emphases of artifacts Jewish features, skew the objects ultimate analysis. In this study, dierent sets of questions that eschew rigid systems of classication permit attention to greater ranges of acceptable Jewish practice and representation. They replace the question: is it [the object] Jewish? with questions that invite more open-ended responses. These include:

Works of Paula Fredriksen emphasize this range within Christian literary sources, i.e., What Parting of the Ways? Also see Paula Fredriksen and Oded Irshai in Christianity and Judaism in Late Antiquity: Polemics and Policies from the Second to Seventh Centuries, in The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period (ed. Steven T. Katz; The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 977-1035. The reconsideration of a range of Jewish and Christian materials removes the limitations imposed by scholars denitions of Jewish and Christian artifacts. Such corrections permit the reconsideration of some objects, such as the Boston bowl, as possibly Jewish. This procedure raises additional possibilities about ranges of North African Jewish funerary or votive practices and prompts additional questions about Jewish and Christian visual representation in antiquity. 33) The additional recycling of queries about whether or not an artifact might be Jewish, ultimately adds little to improved understandings of the artifacts and the cultures that produced them. This is why dierent, and more productive questions are required. See discussion in Seth Schwartz, Imperialism and Jewish Society: 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 276-77. 34) See treatments in Kraemer, Jewish Tuna, and Van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs, respectively.

32)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 13

4/17/08 7:23:48 PM

14

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

What is the range of cultural elements exemplied in an artifact? Where, if at all, do noticeably Jewish elements appear on an artifact? How do indices of Jewishness manifest themselves? How is Jewishness circumscribed by this artifact, if at all? These reformed questions endeavor artifacts more comprehensive examination and permit possibilities of local manifestations of Jewish practice to replace anticipated paradigms for pan-Mediterranean Jewish representation.35 Brief reevaluations of selected artifacts, which scholars conventionally overlook, demonstrate the need to challenge imposed limitations on North African Jewish corpora. When categorized and questioned dierently, these artifacts raise new possibilities for interpretation of Jewish culture in Africa and the broader Mediterranean.

Avoiding a Monolithic Jewishness: Countering Illusions of Identiability and Normalcy in Jewish Archaeology

In memory of the son/daughter of Abedo. He/she lived 7 years. Peace to him/her; Bardo Museum, Tunisia Photo: Author

One epitaph, stored within the archives of the Bardo Museum in Tunis, both exemplies the limitations of exclusively emphasizing an artifacts Jewish aspects, and also demonstrates the advantages of a reformed approach (Figure 2). Over 100 years ago, French soldiers discovered this epitaph when they accidentally exposed an ancient necropolis in Thina,

35)

These paradigms are developed by scholars in response to denitions provided within rabbinic and Christian texts (in the absence of local Jewish texts) about what a Jew is. For extensive discussion, see Shaye Cohen, The Beginnings of Jewishness (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). Both rabbinic and Christian texts possess operative polemical goals in their representations. See Daniel Boyarin, Dying for God: Martyrdom and the Making of Christianity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 26.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 14

4/17/08 7:23:48 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

15

Figure 2. Epitaph reads: Memoria | Abedeunis | Bicsit anos | VII 36 outside the modern Tunisian city of Sfax.37 The inscription is bilingual, with orthographic irregularities in its Latin and Hebrew scripts. It reads: Memoria / Abdeunis / Bicsit anos / VII ,38 in memory of the

Gauckler, Catalogue, 103, no. 1257; R. Cagnat, A. Merlin, and L. Chatelain, Inscriptions latines dAfrique (Tripolitaine, Tunisie et Maroc) (Vol. II; Paris: Leroux, 1923), no. 36; E. Diehl, Inscriptiones Latinae Christianae Veteres (Berolini apud Weidmanns, 1967), no. 4960; Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 7; Zeneb Ben Abdallah, Catalogue des inscriptions latines paennes du Muse du Bardo (Rome: cole Franaise de Rome, 1986), no. 158. 37) The French soldiers had been digging the earth outside Sfax for a military installation when they uncovered a necropolis and this text beneath. The area is presently cut o from Sfax by a series of highways in a small nature preserve. The excavations of early Roman materials from the region are also documented, cf. M. Barrier and M. Benson, Fouilles Thina, BCTH (1908): 22-63. 38) For regionally idiosyncratic representations of Roman numerals in Africa and elsewhere, see, Numerorum Formae Notabiliores, in CIL 8, suppl. 5.3, 306.

36)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 15

4/17/08 7:23:48 PM

16

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

son/daughter of Abedo. He/she lived 7 years. Peace be to him/her.39 North African Roman numerals indicate the age of the deceased (7), and two menorot border the bottom of the inscription.40

39) Translations of the text and determinations of the gender of the deceased vary according to scholars transcriptions and interpretations of the last Hebrew word in the inscription. Le Bohec translates the Hebrew text as la paix (soit) sur elle (?), in Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 7; while Diehl translates the text as pax illi, ILCV, no. 4960; Cagnat translates the Hebrew as pax ei in ILAfr, no. 36; while Ben Abdallah interprets the text to commemorate a male and translates the Hebrew text to read Paix sur lui in Catalogue, no. 158. For readings of a , rather than a following the in the Hebrew text, see the transliteration in Le Bohec, SLM LH in Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 7; and the transcription of Ben Abdallah in Catalogue, no. 158, VI. , which may include additional typesetting errors in the Hebrew. 40) This inscription remains in the archives of the Bardo Museum in Tunis and its photo is preserved in Ben Abdallah, Catalogue, no. 158. Irregularities of the steles preservation and the inscriptions orthography obscure certain aspects of its interpretation. The stone displays at least three major inconsistencies of orthography within the renderings of (1) Abedeunis, (2) vixit, and (3) the Hebrew text. The root of the name, ABD, or servant of, is a common Punic and Neo-Punic onomastic root and varied spellings of the name are found throughout North Africa, as discussed in Zeneb Ben Abdallah and Leila Ladjimi Seba, Index onomastique des inscriptions latines de la Tunisie (Paris: ditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientique, 1983), 23, 23. Also common is the addition of a Greek genitive sux to the names Semitic root, e.g., Abedonis (e.g., CIL 8:10475.4; = 22646.6). Bixit, too, follows common local patterns of the replacement of a V with a B in inscriptions. The last matter of the letter following the in the Hebrew text, however, presents a greater obstacle for interpreting the gender of the deceased. Reading the letter as which follows the yields a feminine personal sux that would suggest a female gender for the deceased. K. Jongeling, North-African Names from Latin Sources (Leiden: Research School CNWS, 1994), 3, thinks it is highly improbable that the name contains the masculine name element bd, since a female is indicated; therefore he suggests it might be a form of habetdeus. Ben Abdallah makes a similar suggestion and states that Une contamination avec le nom unique Habet deum (souvent cit Abeddeum), frquent dans les contextes chrtiens ds le dbut du IVe sicle, nest pas impossible, Catalogue, no. 158. While Jongelings and Ben Abdallahs readings respond to the possibilities of alternative renderings of similarly vocalized names, I would argue against the necessity of dierently reading the names root to account for the female gender of the deceased indicated by the Hebrew sux. Renderings of Hebrew in most North African inscriptions remain exceedingly limited and there is little reason to believe that North African Jews actually understood or easily manipulated classical Hebrew grammar. Repeated renderings of Shalom on inscriptions, for example, may indicate that North African Jewish populations may have copied this limited Hebrew sentiment from a static paradigm. As neither Latin nor Hebrew orthography is consistent in the region, furthermore, there might be little correspondence between the sux used in the Hebrew text and the actual gender of the deceased indicated by the Punic root of the name.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 16

4/17/08 7:23:49 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

17

Scholars have, traditionally, drawn attention to only two of the texts most obvious features: its depiction of two menorot and its use of Hebrew.41 These attributes have led scholars to classify it as one of a group of texts with clear and unambiguous displays of Jewishness. Unlike some other artifacts, this inscription employs overtly Jewish markers; both Yann Le Bohec and Zeinab Ben Abdallah label the epitaph, accordingly, as of a juif.42 Le Bohec assumes that these Jewish epigraphic features necessarily correspond to normative Jewish cultural practice of the commemorator.43 To this point, the classication of the stone as Jewish has been considered sucient to describe it, so that complicating traits, such as its conation of diverse scripts, names, numerals, and languages, remain suppressed. Could attention to these additional aspects of the epigraphic eld, however, contribute to a more meaningful analysis of the stone than previous perspectives have provided? Why ought the discussion of the inscriptions cultural context relate only to its use of Hebrew letters and carved menorot? An artifacts most apparent features can sometimes be its most deceptive. Artistic symbols, such as menorot, inscriptions of Hebrew letters, and allocation of Biblical names, are all considered to be immediately identiable markers of Jewishness par excellence.44 Scholars frequently consider artifacts that contain such markings to be, in some way, undoubtedly Jewish, but those without them, impossibly so. Such a process of identication and analysis, initially, might appear logicaland obviousto nonspecialists. An unforeseen eect of this facile identiability of Jewish elements, however, can ultimately obscure other non-Jewish aspects. Many artifacts, in addition to explicit markings of menorot, biblical names,

For this reason, I suggest that epigraphic evidence for the gender of the deceased remains inconclusive. In all cases, the matter of the gender of the deceased does not impact the broader argument at hand. 41) See examples in Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, 174 and A. Merlin, Notes, BCTH (1919), cciv-ccv. 42) Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 7, Ben Abdallah, Catalogue des Inscriptions, no. 158. Of course, this epitaph could mark the tomb of a female or male child. As discussed in notes 39 and 30 above, the orthographic irregularities of the inscription obscure the gender of the deceased. 43) Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, 168; also Fine, Art and Judaism, 36. 44) Ross Kraemer, Jewish Tuna; Van der Horst, Ancient Jewish Epitaphs; Rachel Hachlili, The Menorah, the Ancient Seven-Armed Candelabrum: Origin, Form, and Signicance (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 17

4/17/08 7:23:49 PM

18

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

or declarations of Iudeus, simultaneously bear additional types of cultural indices. Why should other, non-Jewish symbols on an artifact be ignored in its assessment? A closer, but dierent examination of the epitaph reveals its simultaneous inclusion of a more complex set of cultural markers than traditional analyses of it have permitted. First, it demonstrates a practice most popular within early Christian epitaphs in North Africait records the Latin funerary formula, memoria, in a Latin script.45 Second, the name of the deceased conates two distinct naming systems: Abedo is a conventional name for North African males of Punic descent, while this name, Abedeunis, demonstrates a method of recording liation that is typical of Greek onomastics throughout the Mediterranean.46 The bottom portion of the text uses a Semitic script to record a Hebrew phrase, , or peace to him/her.47 Finally, two menorot, denitively Jewish symbols, are incised at the bottom of the inscription. It is of critical importance to explore each of these linguistic and symbolic idiosyncrasies. Just as menorot might signify Jewishness, so too, may other formulae indicate concurrent cultural identications.48 The

Memoria, became a popular marker for a martyrs tomb in North Africa, particularly in the late third and early fourth centuries. See discussion in J.B. Ward-Perkins, Memoria, Martyrs Tomb and Martyrs Church, Akten des VII Internationalen Kongresses fr Christliche Archologie I (1965), 3-25, and W.H.C. Frend, The North African Cult of the Martyrs, JbAC 9 (1982): 154-67. 46) This name utilizes a Greek genitive form, in the Latin, to express that the deceased is actually the son of Abedo. Other Neo-Punic instances of this name occur in the nominative; an Abedo is commorated on a stele which Delattre attributes to the Punic poque, in A. Delattre, Gamart ou la ncropole juive de Carthage (Lyon: Mougin-Rusand, 1895), 5-6. 47) The funerary formula (inclusion of age at death) remains conventional for Latin epitaphs throughout North Africa. See e.g., Ben Abdallah, Catalogue, nos. 155-157. 48) Attention to language and script patterns in Jewish epitaphs ultimately contributes to more precise understandings of Jewish identity within North Africa. The function of commemorative texts, after all, is not only limited to the act of recording the name of the deceased, or the placement of symbols on an epitaph. For related discussion, see John Bodel, Epigraphic Evidence: Ancient History from Inscriptions (London: Routledge, 2000), 2. The phrases, epithets, languages, and scripts employed on an epitaph also serve as deliberate and public displays of the status, patriline, education, and values of that individual. Through each of these aspects, commemorative language can serve as an encoded systemthe subtlest of its rearrangements, variations, and inections may deliberately convey specic cultural information. For such tendencies in speech, consult treatment in Daniel Fishman, Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 152-53.

45)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 18

4/17/08 7:23:49 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

19

general appearance and features of the artifact strongly resemble others discovered in the same region of ancient Thina.49 The majority of the inscription is in Latinthe most common epigraphic language of the region. The desirability of the common Christian incipit, memoria, and the modication of a Punic name (Abedo) with its Greek patronymic form (Abdeunis), place the epitaph squarely within the commemorative patterns of normative indigenous, and North African groups, variously of Punic descent or cultural context, which inhabited an increasingly Christian African world.50 The epitaphs synthesis of all of these features points to the commemorators embrace of, and embeddedness in, a complex cultic, linguistic, and onomastic environment in Africa Proconsularis. Why should its Jewish features be foregrounded at the expense of local, conventional features? By attending to an inscriptions most Jewish features, scholars do answer the implicit question, is the artifact really Jewish? But these approaches also perpetuate false assumptions about Jewish cultural uniformity in antiquity, and tell us far too little about the particular cultural situation of an individual artifact and its creator. Abdeunis epitaph exemplies the distortion imposed by scholars classication of an object as Jewish and emphasis on its Jewish traits alone. Such traditional approaches only permit scholars to say that Abdeunis commemorator used symbols to identify the deceased with other Jewish groups from North Africa and elsewhere in the Mediterranean. This tells us nothing about his cultural situationwhy he favored specic names for his progeny, the languages he actually spoke, his values, or whether he was an immigrant or a long-term resident of this African region. What are the ramications of the more contextual examination suggested here? A contrasting and richer picture emerges when we begin to notice other features of the artifact. First, the commemorator named his/ her child just as other North Africans, presumably of Neo-Punic descent, also named their children. The commemorator found it acceptable, at least, and desirable, at best, to use the esteemed vocabulary of Christian martyrdom (memoria) to commemorate his child. The majority of the inscription is in Latinunusual for Jews in the Mediterranean, but entirely

49)

This region now borders the modern Tunisian city of Sfax. For comparable regional inscriptions, see R. Cagnat, A. Merlin, and L. Chatelain, Inscriptions latines dAfrique (Tripolitaine, Tunisie et Maroc) (Vol. II; Paris: Leroux, 1923), no. 35, 37. 50) See note 39 above and Ben Abdallah and Seba, Index onomastique, 23, 33.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 19

4/17/08 7:23:50 PM

20

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

prevalent among most North Africans of the western provinces. The Roman numerals that mark the age of the child at death are rendered in typically North African ways.51 The general appearance of the stone is locally conventional. When the commemorator incises distinctly Jewish symbols on the epitaph, he marks the Jewish identity of a child who was named, spoke, and began to grow up, in a thoroughly integrated North African world. Does this artifact demonstrate what many are wont to call assimilation? Why would not such a designation suce to describe the epitaph, which demonstrates Jewish/non-Jewish merging? Assimilation, and its companion, syncretism, remain popular terms to describe artifacts and practices that exhibit both Jewish and non-Jewish features.52 Such vocabulary, however, implicitly depends on problematic and articial cultural models and forces polarities, dichotomies, and divisions on cultures whose identifying features are not mutually exclusive. In that schema, Jewish and non-Jewish cultures are considered opposites: syncretistic, or assimilated, objects/cultures are those that fall somewhere in between the Jewish and the non-Jewish. This epitaph, however, demonstrates the limitations of these assimilation/syncretism modelsafter all, they impose articial divisions on complex matrices of ancient culture. Assessments of this artifact as that of an assimilated Jew, in North Africa, are as misleading and limited, as they are non-descriptive and imprecise. This preferred approach, rather, examines exactly how the artifact employs tools of a local environment to express an idiosyncratic local manifestation of Jewish culture; it does not assume that it merges the traits of a nite culture A with a nite culture B, because North African culture was too multifaceted and complex to be simplied in this way.

51) 52)

Discussion in Bodel, Epigraphic Evidence, 1-56. This model posits that a pure indigenous population slowly adopts the practices, languages, customs, etc., of an entirely new group, to increasingly resemble it. The assimilation model relates to these understandings, and describes the ow of one cultural entity into another, cf. Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries (New Haven: Yale, 1997), 148. The concept of syncretism similarly describes the possibility that two pristine cultural components can be simply combined. Approaches by Romanists such as Greg Woolf and Peter Van Dommelen raise useful arguments that religion, like culture, is fundamentally indivisible and cannot be cut into clear and distinct components to be syncretized. See extensive discussions in Greg Woolf, Beyond Romans and Natives, World Archaeology 28 (1997): 339-50; and Peter Van Dommelen, Colonial Constructs: Colonialism and Archaeology in the Mediterranean, World Archaeology 28 (1997): 31-49.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 20

4/17/08 7:23:50 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

21

Contingencies of preservation prevent any knowledge about the actual life of the commemorator of this epitaph, or the deceased it commemorates. Spaces certainly exist even between the act of inscribing the stone, the life and culture of the commemorator and the commemorated.53 This distinct approach, however, regardless of all necessary limitations, facilitates a vastly improved understanding of the cultural context of the individuals involved.54 A careful unpacking and analysis of all linguistic and symbolic patterns within Jewish texts, not just the presence of Hebrew or biblical quotations, oers an opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of how North African Jews chose to describe the identities of the deceased within their local environments and conceptual frameworks.

Acknowledging Multiple Normalcies in Jewish Culture The Boston bowl and the Abdeunis epitaph exemplify the limitations imposed by common methods of Jewish artifact classication. Another genre of artifact, however, demonstrates why rigid and exclusive denitions of Jewish and Christian artifacts further confound archaeological analysis; conventional archaeological categories that impose ranges of normalcy for Jewish and Christian symbolizations and artifacts cannot accommodate more realistic and complex cultural models. Only with respect to scholarly categories are such hybrid African artifacts abnormal: roughly 20% of Jewish epitaphs from North Africa concurrently bear explicit cult markers of pagan, and Christian identication and practice.55 While scholars have traditionally treated as abnormal or

It is to be presumed that in most cases, commemorators were not inscribing tombstones themselves. No matter how rough-hewn the epitaph, a specialist would probably have been called upon to complete the stone. For such reasons, there cannot be a one-to-one correlation between the languages and representations on the tombstone and those used on a daily basis by the person who commissioned the stone. One can minimally assume, however, that the person who commissioned an epitaph would only use that epitaph if it were minimally acceptable to him or her. 54) See analysis of Bodel, Epigraphic Evidence, 5-6. 55) Cult here designates those elements that specically relate to deity, or worship of deity. All inscriptions combine diverse cultural indices. I emphasize one category of them here, but not to the absolute exclusion of its other features. I use terms of cult, rather than religion, for greater precision: the epitaph and the symbols on it simultaneously serve other functions as well. See related discussion in J.Z. Smith, Imagining Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982).

53)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 21

4/17/08 7:23:50 PM

22

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

interstitial those artifacts that overtly and simultaneously display multiple religious symbols, these tendencies are relatively conventional in North African Jewish art.56 One manifestation of these concurrent symbols is that of a merged Jewish and Christian symbolthat of a menorah and a cross. The catacombs of Gammarth, 17 km north of Tunisthe most concentrated source of Jewish funerary archaeology in North Africaprovide one example of this design (Figure 3).57 The epitaph initially appears to exemplify the iconography and epigraphy of the most conventional Jewish funerary commemoration: the marble surface is carved with two menorot, a shofar, ethrog, and an inscription of shalom in Hebrew.58 Traces of red paint still remain in the incisions on the stone. Upon closer examination, however, one notices that an additional symbolthat of a crossprovides the structure for each of the epitaphs menorot.59 One might consider this Gammarth conguration of a menorah and a cross as accidental, if it were entirely uncommon in North Africa. But this merged symbol appears in third-fourth-century funerary epigraphy from all regions of North Africa. One funerary grato from a catacomb in Tripolitania contains a similar image; Romanelli describes it as a menorah with nine straight branches and a straight horizontal base, which is bisected by a cross-like superstructure (il grato con candelabro e crisma stilizzato su un tumulo deposto al pede (Figure 4).60

These are artifacts that most frequently earn participial, or, hyphenated classications, such as judasant in Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes; Judaizing-Pagan, or Christianizing-Jewish, cf. Setzer, Jews, Judaizers, 185-200. 57) While some epitaphs from the catacombs consist of names of the deceased painted onto terracotta tile, other epitaphs from the region include Jewish symbols and Hebrew letters incised on marble plaques. 58) Rachel Hachlili, Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices, and Rites in the Second Temple Period (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 138-40. 59) It includes two menorot with curved tripod bases, a palm, shofar, and ethrog, and is inscribed with the Hebrew text for Shalom. 60) Photographs and drawings reproduced in P. Romanelli, Una piccola catacomba giudaica di Tripoli, Quad. Arch. Lib. 9 (1977): 111-18; 112, g. 3. The shape of the image resembles the menorah from Kissera (CIL 8:750a-d), but not the one from Gammarth. Two outward-leaning palms also ank the image. This grato was discovered in the proximity of multiple other depictions of menorot, which do not exhibit internal crosses. Unfortunately, these cannot be reviewed in situthe early drawings provide the best documentation for the tombit was bombed in World War II (118). Other artifacts, such as lamps, depict similar images, e.g., Yann Le Bohec. Les sources archologiques du judasme africain sous lEmpire romain, in J.-M. Lassre, Juifs et judasme en Afrique du Nord, 13-64.

56)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 22

4/17/08 7:23:50 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

23

Figure 3. Marble funerary stele incised and painted with crossed menorot and inscription, Gammarth catacombs; Carthage Museum, Tunisia Photo: Author

Figure 4. Menorah grato and its placement on wall of catacomb in Oea; Tripoli, Libya Sketch: Romanelli 1977, 112, g. 3

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 23

4/17/08 7:23:50 PM

24

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

Another artifact from the ancient town of Chusira (Kissera) in Algeria, bears a symbol of an equilateral cross; four diagonal branches extend upward from its center, and an omega and an alpha occupy opposite lower sectors of its quadrant (Figure 6);61 the resulting image depicts a menorah protruding from a cross.62 In a comparable manner, this image explicitly combines a symbolic representation for Christ with that of menorah.63 Some might argue that such symbols are not synthetic because the Christian component of the sign might be anachronisticthat these Christian symbols were not yet used as Christian markers by contemporaneous and local populations. Within each area where the merged symbols have been discovered, however, the equilateral and Latin cross, in addition to that of the Chi Rho, were used as distinct Christian symbols during the same periods (Figure 6).64 The cross portion of these images, therefore, represents an identity symbol that local Christian populations used concurrently. Most scholars analyses of such combined symbols have been brief or apologetic because the Christianizing of the menorah is discomting to some. Hachlili asserts that only Christian groups, which would have appro-

Reproduction of sketch from CIL 8:705d. The elaboration of a cross symbol is common among Christian artifacts of the fourth through sixth centuries: crosses are occasionally extended into forms resembling the symbol of the Neo-Punic Tanit, or letters are attached to the tip of each cross in extended formations (e.g., Liliane Ennabli, Catalogue des inscriptions chrtiennes sur pierre du Muse du Bardo [Tunis: INP, 2000], no. 36). Byzantine lead seals from Carthage frequently present other symbols or letters extending from the structure of a cross. See P. Icard, Notes, BCTH 1917; and Notes, BCTH 1919. In such cases, the images conventionally associated with one cultic sphere appear to modify expressions of the other. This image of the menorah cross serves as an additional example of this trend. 63) This stone consists of four pieces, three of which are inscribed with Latin text and script (CIL 8:705a-d). CIL 8:705a = CIL 8:23781, cf. ILT 584. This particular gure (705d) has not been reexamined in CIL. This image was reproduced in Goodenoughs treatment of diaspora Symbols, but was overlooked in subsequent analyses of Jewish materials; E.R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period (New York: Pantheon, 19531968), vol. 2. The stone was discovered embedded in Algerian fortications, which postdated the Arab conquest, but the stone was subsequently lost. 64) In Proconsularis, see examples from Kissera, e.g., CIL 8:705d; in Tripolitania, see illustrations of S. Aurigemma, Larea cemeteriale cristiana di in Zra (Rome: Ponticio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana, 1932), tombs 54, 56; Aurigemma notes the frequency of the appearance of the Latin cross within the iconography at in Zra in the Tripolitanian desert, ibid., 195, 238-39.

62)

61)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 24

4/17/08 7:23:52 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

25

Figure 5. Drawing of shattered entablature engraved with cross/menorah symbol, Kissera, Algeria Sketch: CIL 8:705d; reproduced with permission of the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften

Figure 6. Sketch of Latin crosses present within burial complex at in Zra in Libya Sketch: Aurigemma 1932, tab. 7; reproduced with permission of the Ponticio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana priated Jewish imagery, would have produced such imperfect representations of the menorah.65 Similarly, Simon considers such images to be

65)

Hachlili, Menorah, 202. This vague use of appropriation is problematic because it summarily eliminates the possibility that those who considered themselves to be true Jews could have been unproblematically incorporating Christian imagery or ideas. As such, the variations in the symbols depiction demonstrate an important point about the use of the menorah itself in North Africa. The symbol may have been viewed as malleable, or able to be tailored to the interests of those who engrave it.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 25

4/17/08 7:23:52 PM

26

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

Christian representations of their belief in the two stages of revelation.66 Le Bohec identies the symbols as Jewish, but, when he evaluates a similar image on a North African lamp, he declares the impossibility of this combination of a menorah and a cross: Cette religion [Judaism] honore un Dieu unique: la croix que lon a pens voir sur les lampes la menorah de Nundinus, pourrait bien ntre que le Tav, la dernire lettre de lalphabet hbreu, symbole qui, prcisment, dsigne Dieu.67 Yet, in each of these cases, the cross formation at the center of the menorah cannot simply be excused as an accident, a Hebrew letter, or the sign of a misplaced Christian artifact.68 These artifacts, rather, represent clear, positive, and concurrent identications with Jewish and Christian theology, and exhibit them within distinctly Jewish contexts. They mark the burial spaces of Jews, who simultaneously embraced Jewish and Christian prescriptions for the divine. These commemorative images pose problems for contemporary scholars, but there is no indication that they did for the ancients who used them. At the very least, they indicate that those Jews who rendered these images were not disturbed by Christian groups contemporaneous use of these symbols. They may not have been sensitive to the cross integration into the structure of the menorah, or to variations in the menorah itself.69

66) Marcel Simon, Le chandelier sept branchessymbole chrtien? in Recherches dhistoire Judo-Chrtienne (ed. Marcel Simon; Paris: Mouton & Co., 1962). 67) Le Bohec, Les sources archologiques, 20. 68) This explanation of the symbol as a Tav is problematic at the most basic of levels there is no evidence that Proconsular Jews even knew what a Hebrew Tav was. Though various epitaphs include the Hebrew word Shalom, they do not provide any indication that the word was anything but a symbol. See Hayim Lapin, Palestinian Inscriptions and Jewish Ethnicity in Late Antiquity, in Galilee Through the Centuries: Conuence of Cultures (ed. Eric Meyers; Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1999), 239-67. Aside from one more extensive epitaph in Hebrew from Mauretania Tingitania (Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 82), no evidence exists that Jews in North Africa composed inscriptions in Hebrew. 69) The appearance of the non-seven branched menorot in non-burial contexts is confusing for similar reasons. It is unclear whether these designs may have been produced by/for groups other than the populations identied with more certainty in burial contexts. Is it possible that either pagans or Christians might have adopted the image as a symbol, rather than as a representation of a sort of practice or ideology? A cluster of menorah images from Oea, in Tripolitania, depicts the varying possibilities of representations of the number of branches of menorot. In one burial complex, some menorot are depicted with seven-branches, while others might have nine or twelve, as in Romanelli, Una piccola

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 26

4/17/08 7:23:53 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

27

At most, combinations of the menorah and cross indicate the degree to which some people saw it as possible, appropriate and desirable to identify simultaneously with the multiple gods and practices that the two images independently symbolize.70 Scholars consider the menorah to be a clearly recognized symbol of Jewish identity.71 Yet the creative and explicit modication of this sign with another one implies a more complex type of indexicality and, perhaps, an indication of a more complex type of divine supplication in response to a beloveds death.72 To these deceased, perhaps Jewish and Christian gods were contiguous, identical, or multiple. To their commemorators, their

catacomba, 112, g. 3. Certain scholars, such as Rachel Hachlili, directly correlate deviations in menorah design (from the seven-branched tripod base form) with a diering underlying ideology; Hachlili, Menorah, 200-201. She also suggests that they, alternatively, may have been mistakes or produced by less than perfect workmanship (ibid., 202). These Tripolitanian images do not necessarily suggest such conclusions. It is unclear whether distinct numbers of branches of a menorah might indicate distinct ideologies, practices, or simply an emulation of a distinct design. 70) The combination of the image of the menorah with that of a cross has been recognized elsewhere in the Mediterranean. In her examination of the origin, form and signicance of the menorah, Rachel Hachlili has noted patterns of representing crosses within menorot in Roman Palestine in Hachlili, Menorah, 270-72. Hachlili has stated that some of these images are not of menorot at all, but of the tree of life. This interpretation would discount the possibility of their simultaneously serving as menorot and crosses. She describes that most of the attested instances of such combinations derive from sites identied as Christian, ibid., 272, although the criteria for identifying these sites as Christian are unclear. Zvi Maoz takes similar positions toward menorot in Christian sites, Comments on Jewish and Christian Communities in Byzantine Palestine, PEQ 117 (1985): 63. Other chancel screens within churches in the Palestinian region pair distinct images of the menorah with those of the cross. One architectural fragment from fourth to fth-century Sicily, in the town of Catania, pairs the images of an encircled cross next to that of a ve-armed menorah, cf., N. Bucaria, Sicilia Judaica (Palermo: Flaccovio, 1996), 54, g. 5; Hachlili, Menorah, 274, g. D6.16). Specic North African Jewish epitaphs, such as this, have been viewed with comparable discomfort by the scholars who have studied them. 71) See discussion in Hachlili, Menorah, 280. 72) Whether the image resembled a normative menorah with seven curved branches, a Neo-Punic-like representation, or one combined with a cross, it signied a range of acceptable and possible practices to commemorate the deceased. It symbolizes allegiance with a set of ideals or ideas (perhaps, even, ethnicity), but in no case does it represent the same ideals or ideas in any given instance. Just as the form of the image may be mutable, so too may the identities that the image symbolizes and the deities to whom it refers. Though the menorah is the Jewish symbol par excellence, cf. Hachlili, Menorah, 177, the meaning of par excellence changes according dierent persons, places and times.

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 27

4/17/08 7:23:53 PM

28

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

simultaneous supplication was both appropriate and desirable. As the menorah and cross markers indicate, ancient conceptions of deity/deities were more complex and uid than modern taxonomies of Jewish monotheism permit.73 While some Jews may have viewed a simple menorah as the only appropriate symbol to adorn an epitaph, others disagreed. At times of burial, other African Jews engraved commemorative symbols onto their epitaphs that evoked the theological, funerary, and burial practices of contemporary Neo-Punic, Roman, and Christian groups.74 Did these Jews envision pagan and Christian deities as continuous with their own? Or, alternatively, did sorrow prompt mourners to appeal to a range of deities they otherwise understood to be distinct? The answers to these questions are impossible to discern, because ancient beliefs ultimately remain elusive. What is most conclusive about these images, however, is their frequencymerged symbols of African Jewish, Christian and pagan deity are common enough in the archaeological record that such patterns appear to be relatively conventional. Why should scholars ignore, describe as accidental, or label as Christian, those artifacts with features, such as images of crosses within menorot? Should artifacts be forced into categories of normative Jewish representation, such that all others are rendered liminal by their traits that resist scholars established views of ancient Judaism? Merged symbols are pervasive enough among North African inscriptions to indicate that some Jews possessed more complex understandings of divine supplication than traditional historical and theological models can accommodate.

Conclusion A brief survey shows that the prevalent methods for studying ancient Judaism, on which scholars dominant theories rely, are inadequate, because they depend upon rigid essentialist or syncretistic models of cultural dynamics. There is no Platonic form of ancient Jewishness, just as there

This tendency also expresses itself within earlier periods. During the earlier empire, Jewish symbols also coincide with markers of specically pagan devotional practice. On selected epitaphs Jewish names are joined with the inscribed dedication of the deceased to the DMSDis Manibus Sanctumthe divine shades of the underworld, e.g., Le Bohec, Inscriptions juives et judasantes, no. 12. 74) See treatment in Paula Fredriksen, Gods and One God: In Antiquity, all Monotheists were Polytheists, BRev 18 (2003): 32.

73)

JSJ 39,3_423_f1_1-31.indd 28

4/17/08 7:23:53 PM

K. Stern / Journal for the Study of Judaism 39 (2008) 1-31

29