Professional Documents

Culture Documents

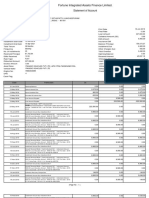

3y1s Tax F 1 Fullshem

Uploaded by

Wolf DenOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

3y1s Tax F 1 Fullshem

Uploaded by

Wolf DenCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

L-12798

May 30, 1960

VISAYAN CEBU TERMINAL CO., INC., petitioner-appellant, vs. COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE, respondent-appellee. Duterte and Rodriguez for petitioner. Assistant Solicitor General Jose P. Alejandro and Atty. Sixto J. Javier for respondent. CONCEPCION, J.: Petitioner Visayan Cebu Terminal Co., Inc., seeks a review of the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals in the above entitled case. The dispositive part of said decision reads as follows: FOR THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATIONS, the decision appealed from is hereby modified, and appellant is hereby ordered to pay the Collector of Internal Revenue, within a reasonable period to be fixed by the latter, the sum of P15,517.00, computed below: Net income per return P41,596.45 Disallowances: (1) Salaries 500.00 (2) Representation Expenses: As claimed by appellant 75,855.88 Allowed 10,000.00 65,855.88 (3) Miscellaneous expenses 5,768.00 Net income subject to tax P113,720.33 Tax due on P113,720.33: P100,000.00 at 20% P20,000.00 P13,720.00 at 28% 3,842.00 P23,842.00 Less tax previously assessed and paid 8,325.00 Deficiency tax P15,517.00 With costs against appellant. The facts, which are not disputed, are set forth in the aforementioned decision, from which we quote: "The appellant, Visayan Terminal Co. Inc., is a corporation organized for the purpose of handling arrastre operations in the port of Cebu. It was awarded the contract for the said arrastre operations by the Bureau of Customs, pursuant to Act No. 3002, as amended. "On March 1, 1952, appellant filed its income tax return for 1951 reporting a gross income of P420,633.40 and claimed deductions amounting to P379,036.95, leaving a net income of

P41,596.45 on which it paid income tax in the sum of P8,319.20. The sum of P379,036.95 claimed as deductions consisted of various items, among which were the following: 1. Salaries (a) Salary and bonus of Juan Eugenio Lo P1,875.00 (b) Salary of Felix Go Chan 250.00 (c) Salary of Teomino Tiu Tiam 250.00 P 2,375.00 2. Representation expenses 75,855.88 3. Miscellaneous expenses (a) Christmas bonus given to various persons P1,500.00 (b) Tips to ships' officers 4,800.00 6,300.00 TOTAL P84,530.88 The said sums of P2,375.00, P75,855.88 and P6,300.00, representing salaries, representation expenses and miscellaneous expenses, respectively, or a total of P84,530.88, were disallowed by the Collector of Internal Revenue, thus giving rise to a deficiency assessment of P18,991.00. xxx xxx xxx

Upon request for reconsideration, the Collector modified the deficiency income tax assessment by allowing the deduction from appellant's gross income of the salary of Juan Eugenio Lo in the sum of P1,875.00 and miscellaneous expenses amounting to P532.00, at the same time maintaining the disallowance of the full amount of P75,855.88 as representation expenses. The revised deficiency assessment is itemized in the letter of the Collector dated March 26, 1955, and is reproduced below: Net income as per return P41.596.45 Disallowances: per investigation: salaries of officers P 2,375.00 allowed per reaudit 1,875.00 500.00 per investigation and reaudit, representation expenses 75,855.88 per investigation, miscellaneous expenses 6,300.00 allowed per reaudit 532.00 5,768.00 Net income subject to tax per reaudit P123,720.33 Tax due on P123,720.33: P100,000.00 at 20% P20,000.00 P23,720.00 at 28% 6,642.00 P26,642.00

Less tax previously assessed and paid 8,325.00 Deficiency tax P18,317.00 Add: 5% surcharge 915.85 1% monthly interest from 5/31/53 to 4/30/55 4,212.91 Compromise for late payment 40.00 Total amount due on April 30,1955 P23,485.76 Appellant has agreed to the disallowance of the sum P500.00 representing the salaries of Felix Go Chan and Teotimo Tiu Tiam at P250.00 each, and the sum of P5,768.00, representing miscellaneous expenses. The only issue raised in this appeal relates to the deductibility of the sum of P75,855.88 as representation expenses. Passing upon said issue, which is, also, the only one raised in this appeal, the lower court held that "representation ... expenses fall under the category of business expenses which" are allowable deductions from gross income if they meet the conditions prescribed by law", particularly section 30(a) (1) of the National Internal Revenue Code; that, to be deductible, said business expenses must "ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred in carrying on any trade or business"; that those expenses "must also, meet the further test of reasonableness in amount", this test being "inherent in the phase `ordinary and necessary'"; that some of the representation expenses claimed by appellant had been evidenced by vouchers or chits, but others were reimbursed "without presentation of supporting papers; that the aforementioned vouchers or chits were allegedly "destroyed when the house of Buenaventura M. Veloso, treasurer of appellant, where the records were kept was burned"; that, accordingly, "it is not possible to determine the actual amount covered by supporting papers and the amount without supporting papers"; that the court should, therefore, "determine from all available data the amount properly deductible as representation expenses"; that "during the period of four (4) years from 1949 to 1952, appellant had gross income, net income, net profits and claimed representation expenses as follows: Year Gross Income Net Profit Representation Expenses 1949 P722,135.42 P61,257.53 P83,703.54 1950 451,303.21 33,023.78 10,424.39 1951 420,479.39 41,596.45 75,855.88 1952 425,326.86 34,207.31 63,618.64 and that "from the above figures, we may infer that the sum of P10,000 may be considered reasonably necessary for entertainment expenses of appellant in 1951, it having claimed a little over the amount in 1950, when its gross income was more than its gross income in 1951 and 1952", and because "it allegedly spent for entertainment purposes in 1948 the sum of P500.00 only." Hence, the lower court modified the

assessment of the taxes due from appellant herein the manner set forth in the beginning of this decision. In its brief, appellant does not assail any of the premises upon which the aforementioned conclusion of the lower court was predicated. What is more, it relied upon, and, even, quoted some of the views expressed in the decision appealed from. Appellant, however, maintains that said court had acted arbitrarily in considering the representation expenses in 1950, not those incurred in 1949 and 1952, in fixing the amount deductible in 1951. This pretense is clearly untenable. It appears: (a) that part of the alleged representation expenses had never had any supporting paper; (b) that the vouchers and chits covering other representation expenses had been allegedly destroyed; (c) that there is no documentary evidence on record of any of the representation expenses in question; (d) that no testimonial evidence has been introduced on any specific item of said alleged expenses; (e) that there is no more than oral proof to the effect that payments had been made to appellant's officers for representation expenses allegedly made by the latter and about the general nature of such alleged expenses; (f) that the gross income in 1950 exceeded the gross income in 1951 and 1952, and (g) that the representation expenses in 1948 amounted to P500 only. Under these circumstances, the lower court was fully justified in concluding that the representation expenses in 1951 should be slightly less than those incurred in 1950. Upon the other hand, appellant has not even tried to show why its representation expenses in 1951 should be deemed bigger than the amount allowed by the lower court. In fact, the latter had been patently fair and reasonable, if not rather liberal, in allowing appellant to deduct P10,000.00 as representation expenses for 1951, there being absolutely no concrete evidence of the sums then actually spent for purposes of representation. It may not be amiss to note that the explanation to the effect that the supporting paper of some of those expenses had been destroyed when the house of the treasurer was burned, can hardly be regarded as satisfactory, for appellant's records are supposed to be kept in its offices, not in the residence of one of its officers. Being in accordance with the facts and the law, the decision appealed from is hereby affirmed, with costs against petitioner-appellant, Visayan Cebu Terminal Co., Inc. It is so ordered. Paras, C J., Bengzon, Montemayor, Bautista Angelo, Labrador, Barrera, and Gutierrez David JJ., concur. Kurnzle&Streif, Inc v. CIR - WALA

G.R. No. L-23226

November 28, 1967

ALHAMBRA CIGAR and CIGARETTE MANUFACTURING COMPANY, petitionerappellant,

vs. THE COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, respondent-appellee. Gamboa and Gamboa for petitioner-appellant. Office of the Solicitor General for respondent-appellee. FERNANDO, J.: This Court, in this petition for the review of a decision of the Court of Tax Appeals is not faced with a problem of undue complexity. The law governing the matter has been authoritatively expounded in an opinion by the then Justice, now Chief Justice, Concepcion in Alhambra Cigar v. Collector of Internal Revenue,1 a case involving the same parties over a similar question but covering an earlier period of time. The limits of a power of respondent Commissioner of Internal Revenue to allow deductions from the gross income "the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or increased during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business, including a reasonable allowance for salaries and other compensation for personal services actually rendered . . ."2 had thus been authoritatively expounded. What remains to be decided in this litigation is whether the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals sought to be reviewed reflected with fidelity the doctrine thus announced or deviated therefrom. According to the petition for review, Alhambra Cigar & Cigarette Manufacturing Company, petitioner-appellant, "is a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Philippines, with principal office at 31 Tayuman street, Tondo, Manila; and the respondentappellee is the duly appointed and qualified Commissioner of Internal Revenue, vested with authority to act as such for the Government of the Republic of the Philippines, . . . .3 In the petition for review it was contended that the Court of Tax Appeals, in affirming the action taken by respondent-appellee Commissioner of Internal Revenue, erred "(a) In holding that A. P. Kuenzle and H.A. Streiff who were the President and Vice-President, respectively, of the petitioner-appellant, were entitled to a salary of only P6,000.00 each year, for 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957, and a bonus equal to the reduced bonus of W. Eggmann for each of said years; and disallowing as deductions the portions of their salary and bonus in excess of said amounts; (b) In disallowing, as deductions, all the directors' fees and commissions paid by the petitionerappellant to A.P. Kuenzle and H.A. Streiff; (c) In holding that the petitioner-appellant is liable for the alleged deficiency income taxes in question."4 It is indisputable as noted in the brief for petitioner-appellant that the deductions disallowed by respondent-appellee, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, for the year 1954 to 1957 designated as salaries, officers; bonus, officers; commissions to managers and directors' fees "relate exclusively to the compensations paid by the petitioner-appellant in 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957, to A. P. Kuenzle and H.A. Streiff who were, during the said years, as they had been in prior years and still are, directors and the president and vice-president, respectively, of the petitionerappellant. . . ."5 Under the category of salaries, officers of the fixed annual compensation of A. P. Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff in the amount of P15,000.00 each "the respondent-appellee allowed for each of

them a salary of only P6,000.00 and disallow the balance of P9,000.00, or a total disallowance of P18,00.0,0 for both of them, for each of the years in question."6 Under that of the bonus, officers of the amount under such category paid to the above gentlemen for the year 1954 of P14,750.00 each, "the respondent-appellee allowed each of them a bonus of only P5,850.00, and disallowed the balance of P8,900.00 or a total disallowance of P17,800.00 for both of them."7 For the year 1955, the bonus being paid, once again, amounting to P14,750.00 to each of them, "the respondent-appellee allowed for each of them, a bonus of only P7,000.00, and disallowed the balance of P7,750.00 each, or a total disallowance of P15,500.00 for both of them."8 For the year 1956, again the amount, not suffering any change for each, "the respondent-appellee allowed for each of them a bonus of only P5,500.00 and disallowed the balance of P9,250.00 each, or a total disallowance of P18,500.00 for both of them."9 Lastly, for the year 1957, of a similar amount payable to each in the concept of bonus, "the respondent-appellee allowed for each of them a bonus of only P6,500.00, and disallowed the balance of P8,250.00 each, or a total disallowance of P16,500.00 for both of them."10 As to the deduction in the concept of commissions to managers, the brief for the petitioner appellant states: "The commissions paid by the petitioner-appellant to A. P. Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff in the amount of P13,607.61 each in 1954, or a total of P27,215.22 for both of them; P14,097.62 each in 1955, or a total of P28,195.24 for both of them; P13,180.87 each in 1956, or a total of P26,361.74 for both of them; and P13,144.29 each in 1957, or a total of P26,288.48 for both of them, were entirely disallowed by the respondent-appellee."11 Concerning the directors' fees paid to both officials by petitioner-appellant, it is noted in the brief that "in the amount of P11,504.71 each in 1954, or a total of P23,009.42 for both of them; P10,693.02 each in 1955, or a total of P21,386.04 for both of them; P10,360.23 each in 1956, or a total of P20,720.46 for both of them; and P9,716.63 each in 1957, or a total of P19,433.26 for both of them were also entirely disallowed by the respondent-appellee."12 In the decision of the respondent Court of Tax Appeals sought to be reviewed, there was an appraisal of the evidence on which respondent-appellee Commissioner of Internal Revenue based the above deduction on salaries and bonuses: "The evidence shows that prior to 1954, Messrs. A. P. Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff President and Vice-President, respectively, of petitioner corporation, were each paid an annual salary P6,000.00 and a bonus of about four times as much as the annual salary. In Alhambra Cigar and Cigarette Manufacturing Company v. Coll. of Int. Rev. C.T.A. No. 142 January 31, 1957 (affd. in G.R. Nos. L-12026 & L-12131, May 29, 1959), this Court held that considering the nature of the services performed by Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff the salary of P6,000.00 paid to each of them was reasonable and, therefore, deductions is ordinary and necessary business expense. The bonus paid to each of said officers was however reduced to the amount equivalent to that paid to Mr. W. Eggmann, the resident Treasurer and Manager of petitioner. Following the decision of the Supreme Court in G. R. Nos. L-12026 & L12131, . . ., respondent allowed as deduction P6,000.00 as salary to Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff and a bonus equivalent to that paid annually to Mr. Eggmann from 1954 to 1957, as indicated above."13 Then the decision of respondent Court of Tax Appeals in affirming what respondent-appellee did explained why: "Upon the evidence of record, we find no justification to reverse or modify the

decision of respondent with respect to the disallowance of a portion of the salaries and bonuses paid to Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff. Petitioner seeks to justify the increase in the salaries of Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff on the ground of increased costs of living. The said officers of petitioner are, however, non-residents of the Philippines."14 It may be stated in this connection that the brief for petitioner-appellant did not actually dispute the fact of non-residence of the aforesaid officials. Thus: "A. P. Kuenzle or H. A. Streiff usually came to the Philippines every two years, and generally stayed from five to eight weeks (t.s.n., pp. 203-204). During the years in question, H. A. Streiff was in the Philippines from January 27 to March 20, 1954. He was personally present at the special meeting of the board of directors of the petitioner-appellant on February 19, 1954 and at the regular meeting on February 27, 1954, the minutes of all of which he signed as Vice-President (Exhibits Q, Q-1 and Q-2). He was also personally present at the semi-annual meeting of stockholders of the petitioner-appellant on February 19, 1954, the minutes of which he also signed as vice-president (Exh. R). A. P. Kuenzle was in the Philippines from February 3 to March 8, 1956 (t.s.n., pp. 204-205). He was personally present at the special meeting of the board of directors on February 22, and on February 23, 1956, and at the semi-annual general meeting of stockholders on February 23, 1956, the minutes of all of which he signed as President (Exhs. Q-8, Q-9. and R-4). H. A. Streiff came again to the Philippines in 1958, and he personally attended the special meeting of the board of directors on March 7, 1968, the minutes of which he also, signed as Vice-President (Exh. Q-16)."15 There was in the brief of petitioner-appellant stress laid on those work performed by them, both in and outside the Philippines. "During their stay in the Philippines, A. P. Kuenzle or H. A. Streiff inspected the install petitions of the petitioner-appellant, and discussed with the local management, personnel and management matters, long-range planning and policies of the company (t.s.n., pp. 205-206). Aside from these visits of A. P. Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff to the Philippines, there were other personal consultations between them and the local management. There were about seven staff members in the local management, and each of them went on home leave every four years and for consultations in Switzerland with the general managers, AP Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff. These home leaves each lasted for six months. In this way, at least one staff member went on home leave every year and for consultations with the general manager. . . ."16 As to commissions and directors' fees, it is the finding of the Court of Tax Appeals: "In connection with the commissions paid to Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff there is no evidence of any particular service rendered by them to petitioner to warrant payment of commissions. Counsel for petitioner sought to prove the various types of services performed by said officers, but the services mentioned are those for which they have been more than adequately compensated in the form of salaries and bonuses. As regards the directors' fees, it is admitted that Messrs. Kuenzle and Streiff "usually came to the Philippines every two years, and generally stayed from five to eight weeks." (Page 17, Memorandum for Petitioner.) We cannot see any justification for the payment of director's fees of about P10,000.00 to each of said officers for coming to the Philippines to visit their corporation once in two years. Being non-resident President and VicePresident of Petitioner corporation of which they are the controlling stockholders, we are more inclined to believe that said commissions and directors' fees, payment of which was based on a

certain percentage of the annual profits of petitioner, are in the nature of dividend distributions,"17 Considering how carefully the Court of Tax Appeals considered the matter of the disallowances in the light of Section 30 of the National Internal Revenue Code, the task for petitioner-appellant in proving that it erred in holding that A. P. Kuenzle and H. A. Streiff were entitled only to the salary of P6,000.00 each a year, for 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957, and a bonus equal to the reduced bonus of one of its officials a certain W. Eggmann, for each of said years, and in disallowing as deductions the directors' fees and commissions paid by it to them, was far from easy. Nor could it be said that petitioner-appellant did succeed in such effort As mentioned earlier, the previous case of Alhambra Cigar & Cigarette Manufacturing Company v. The Collector of Internal Revenue,18 has laid down the applicable principle of law. In the language of then Justice, now Chief Justice, Concepcion: "In the light of the tenor of the foregoing provision, whenever a controversy arises on the deductibility, for purposes of income tax, of certain items for alleged compensation of officers of the taxpayer, two (2) questions become material, namely: (a) Have "personal services" been "actually rendered" by said officers? (b) In the affirmative case, what is the "reasonable allowance" therefore? When the Collector of Internal Revenue disallowed the fees, bonuses and commissions aforementioned, and the company appealed therefrom, it became necessary for the [Court of Tax Appeals] to determine whether said officer had correctly applied section 30 of the Tax Code, and this, in turn, required the consideration of the two (2) questions already adverted to. In the circumstances surrounding the case, we are of the opinion that the [Court of Tax Appeals] has correctly construed and applied said provision." So it is now. This appeal too cannot prosper. Even if there were no such previous decision, it would still follow, in the light of the controlling doctrines, that the Court of Tax Appeals must be sustained. The well written brief for petitionerappellant citing Botany Worsted Bills v. United States,19 states: "Whether the amounts disallowed by the respondent-appellee in the respective years were reasonable compensation for personal services, is a question of fact to be determined from all the evidence."20 That the question thus involved is inherently factual, appears to be undeniable. This Court is bound by the finding of facts of the Court of Tax Appeals, especially so, where as here, the evidence in support thereof is more than substantial, only questions of law thus being left open to it for determination.21 Without ignoring this various factors which petitioner-appellant would have this Court consider in passing upon the determination made by the Court of Tax Appeals but with full recognition of the fact that the two officials were non-residents, it cannot be said that it committed the alleged errors, calling for the interposition of the corrective authority of this Court. Nor as a matter of principle is it advisable for this Court to set aside the conclusion reached by an agency such as the Court of Tax Appeals which is, by the very nature of its function, dedicated exclusively to the study and consideration of tax problems and has necessarily developed an expertise on the subject unless, as did not happen here, there has been an abuse or improvident exercise of its authority. WHEREFORE, the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals is affirmed, with costs against petitioner-appellant.

Dizon, Makalintal, Bengzon, J.P., Sanchez, Zaldivar, Castro and Angeles, JJ., concur. Concepcion, C.J., and Reyes, J.B.L., J., took no part.

G.R. No. L-15922

November 29, 1961

C. F. CALANOC, petitioner, vs. THE COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE, respondent. Francisco M. Gonzales for petitioner. Office of the Solicitor General and Special Attorney Librada del Rosario-Natividad for respondent. LABRADOR, J.: This is a petition to review the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals affirming an assessment of P7,378.57, by the Collector of Internal Revenue as amusement tax and surcharge due on a boxing and wrestling exhibition held by petitioner Calanoc on December 3, 1949 at the Rizal Memorial Stadium. By authority of a solicitation permit issued by the Social Welfare Commission on November 24, 1949, whereby the petitioner was authorized to solicit and receive contributions for the orphans and destitute children of the Child Welfare Workers Club of the Commission, the petitioner on December 3, 1949 financed and promoted a boxing and wrestling exhibition at the Rizal Memorial Stadium for the said charitable purpose. Before the exhibition took place, the petitioner applied with the respondent Collector of Internal Revenue for exemption from payment of the amusement tax, relying on the provisions of Section 260 of the National Internal Revenue Code, to which the respondent answered that the exemption depended upon petitioner's compliance with the requirements of law. After the said exhibition, the respondent, through his agent, investigated the tax case of the petitioner, and from the statement of receipts which was furnished the agent, the latter found that the gross sales amounted to P26,553.00; the expenditures incurred was P25,157.62; and the net profit was only P1,375,30. Upon examination of the said receipts, the agent also found the following items of expenditures: (a) P461.65 for police protection; (b) P460.00 for gifts; (c) P1,880.05 for parties; and (d) several items for representation. Out of the proceeds of the exhibition, only P1,375.38 was remitted to the Social Welfare Commission for the said charitable purpose for which the permit was issued. On November 24, 1951, the Collector of Internal Revenue demanded from the petitioner payment of the amount of 533.00; the expenditures incurred was P25,157.62; and the net profit

was only P1,375,38. Upon examination of the Secretary of Finance dated June 15, 1948, authorizing denial of application for exemption from payment of amusement tax in cases where the net proceeds are not substantial or where the expenses are exorbitant. Not satisfied with the assessment imposed upon him, the petitioner brought this case to the Court of Tax Appeals for review. After hearing, the tax court rendered the decision sought herein to be reviewed. Hence, this petition. Before this Court, the petitioner questions the validity of the assessment of P7,378.57 imposed upon him by the respondent, as affirmed by the tax court. He denies having received the stadium fee P1,000, which is not included in the receipts, and claims that if he did, he can not be made to pay almost seven times the amount as amusement tax. But evidence was submitted that while he did not receive said stadium fee of P1,000, said amount was paid by the O-SO Beverages directly to the stadium for advertisement privileges in the evening of the entertainments. As the fee was paid by said concessionaire, petitioner had no right to include the P1,000 stadium fee among the items of his expenses. It results, therefore, that P1,000 went into petitioner's pocket which is not accounted for. Furthermore petitioner admitted that he could not justify the other expenses, such as those for police protection and gifts. He claims further that the accountant who prepared the statement of receipts is already dead and could no longer be questioned on the items contained in said statement. We have examined the records of the case and we agree with the lower court that most of the items of expenditures contained in the statement submitted to the agent are either exorbitant or not supported by receipts. We agree with the tax court that the payment of P461.65 for police protection is illegal as it is a consideration given by the petitioner to the police for the performance by the latter of the functions required of them to be rendered by law. The expenditures of P460.00 for gifts, P1,880.05 for parties and other items for representation are rather excessive, considering that the purpose of the exhibition was for a charitable cause. WHEREFORE, the decision sought herein to be reviewed is hereby affirmed, with costs against the petitioner.

G.R. No. L-13912

September 30, 1960

THE COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. CONSUELO L. VDA. DE PRIETO, respondent. Office of the Solicitor General Edilberto Barot, Solicitor F.R. Rosete and Special Atty. B. Gatdula, Jr. for petitioner. Formilleza and Latorre for respondent.

GUTIERREZ DAVID, J.: This is an appeal from a decision of the Court of tax Appeals reversing the decision of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue which held herein respondent Consuelo L. Vda. de Prieto liable for the payment of the sum of P21,410.38 as deficiency income tax, plus penalties and monthly interest. The case was submitted for decision in the court below upon a stipulation of facts, which for brevity is summarized as follows: On December 4, 1945, the respondent conveyed by way of gifts to her four children, namely, Antonio, Benito, Carmen and Mauro, all surnamed Prieto, real property with a total assessed value of P892,497.50. After the filing of the gift tax returns on or about February 1, 1954, the petitioner Commissioner of Internal Revenue appraised the real property donated for gift tax purposes at P1,231,268.00, and assessed the total sum of P117,706.50 as donor's gift tax, interest and compromises due thereon. Of the total sum of P117,706.50 paid by respondent on April 29, 1954, the sum of P55,978.65 represents the total interest on account of deliquency. This sum of P55,978.65 was claimed as deduction, among others, by respondent in her 1954 income tax return. Petitioner, however, disallowed the claim and as a consequence of such disallowance assessed respondent for 1954 the total sum of P21,410.38 as deficiency income tax due on the aforesaid P55,978.65, including interest up to March 31, 1957, surcharge and compromise for the late payment. Under the law, for interest to be deductible, it must be shown that there be an indebtedness, that there should be interest upon it, and that what is claimed as an interest deduction should have been paid or accrued within the year. It is here conceded that the interest paid by respondent was in consequence of the late payment of her donor's tax, and the same was paid within the year it is sought to be declared. The only question to be determined, as stated by the parties, is whether or not such interest was paid upon an indebtedness within the contemplation of section 30 (b) (1) of the Tax Code, the pertinent part of which reads: SEC. 30 Deductions from gross income. In computing net income there shall be allowed as deductions xxx (b) Interest: (1) In general. The amount of interest paid within the taxable year on indebtedness, except on indebtedness incurred or continued to purchase or carry obligations the interest upon which is exempt from taxation as income under this Title. The term "indebtedness" as used in the Tax Code of the United States containing similar provisions as in the above-quoted section has been defined as an unconditional and legally enforceable obligation for the payment of money.1awphl.nt (Federal Taxes Vol. 2, p. 13,019, Prentice-Hall, Inc.; Merten's Law of Federal Income Taxation, Vol. 4, p. 542.) Within the meaning of that definition, it is apparent that a tax may be considered an indebtedness. As stated xxx xxx

by this Court in the case of Santiago Sambrano vs. Court of Tax Appeals and Collector of Internal Revenue (101 Phil., 1; 53 Off. Gaz., 4839) Although taxes already due have not, strictly speaking, the same concept as debts, they are, however, obligations that may be considered as such. The term "debt" is properly used in a comprehensive sense as embracing not merely money due by contract but whatever one is bound to render to another, either for contract, or the requirement of the law. (Camben vs. Fink Coule and Coke Co. 61 LRA 584) Where statute imposes a personal liability for a tax, the tax becomes, at least in a board sense, a debt. (Idem). A tax is a debt for which a creditor's bill may be brought in a proper case. (State vs. Georgia Co., 19 LRA 485). It follows that the interest paid by herein respondent for the late payment of her donor's tax is deductible from her gross income under section 30(b) of the Tax Code above quoted. The above conclusion finds support in the established jurisprudence in the United States after whose laws our Income Tax Law has been patterned. Thus, under sec. 23(b) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1939, as amended 1 , which contains similarly worded provisions as sec. 30(b) of our Tax Code, the uniform ruling is that interest on taxes is interest on indebtedness and is deductible. (U.S. vs. Jaffray, 306 U.S. 276. See also Lustig vs. U.S., 138 F. Supp. 870; Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Bryer, 151 F. 2d 267, 34 AFTR 151; Penrose vs. U.S. 18 F. Supp. 413, 18 AFTR 1289; Max Thomas Davis, et al. vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 46 U.S. Boared of Tax Appeals Reports, p. 663, citing U.S. vs. Jaffray, 6 Tax Court of United States Reports, p. 255; Armour vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 6 Tax Court of the United States Reports, p. 359; The Koppers Coal Co. vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 7 Tax Court of United States Reports, p. 1209; Toy vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue; Lucas vs. Comm., 34 U.S. Board of Tax Appeals Reports, 877; Evens and Howard Fire Brick Co. vs. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 3 Tax Court of United States Reports, p. 62). The rule applies even though the tax is nondeductible. (Federal Taxes, Vol. 2, Prentice Hall, sec. 163, 13,022; see also Merten's Law of Federal Income Taxation, Vol. 5, pp. 23-24.) To sustain the proposition that the interest payment in question is not deductible for the purpose of computing respondent's net income, petitioner relies heavily on section 80 of Revenue Regulation No. 2 (known as Income Tax Regulation) promulgated by the Department of Finance, which provides that "the word `taxes' means taxes proper and no deductions should be allowed for amounts representing interest, surcharge, or penalties incident to delinquency." The court below, however, held section 80 as inapplicable to the instant case because while it implements sections 30(c) of the Tax Code governing deduction of taxes, the respondent taxpayer seeks to come under section 30(b) of the same Code providing for deduction of interest on indebtedness. We find the lower court's ruling to be correct. Contrary to petitioner's belief, the portion of section 80 of Revenue Regulation No. 2 under consideration has been part and parcel

of the development to the law on deduction of taxes in the United States. (See Capital Bldg. and Loan Assn. vs. Comm., 23 BTA 848. Thus, Mertens in his treatise says: "Penalties are to be distinguished from taxes and they are not deductible under the heading of taxs." . . . Interest on state taxes is not deductible as taxes." (Vol. 5, Law on Federal Income Taxation, pp. 22-23, sec. 27.06, citing cases.) This notwithstanding, courts in that jurisdiction, however, have invariably held that interest on deficiency taxes are deductible, not as taxes, but as interest. (U.S. vs. Jaffray, et al., supra; see also Mertens, sec. 26.09, Vol. 4, p. 552, and cases cited therein.) Section 80 of Revenue Regulation No. 2, therefore, merely incorporated the established application of the tax deduction statute in the United States, where deduction of "taxes" has always been limited to taxes proper and has never included interest on delinquent taxes, penalties and surcharges. To give to the quoted portion of section 80 of our Income Tax Regulations the meaning that the petitioner gives it would run counter to the provision of section 30(b) of the Tax Code and the construction given to it by courts in the United States. Such effect would thus make the regulation invalid for a "regulation which operates to create a rule out of harmony with the statute, is a mere nullity." (Lynch vs. Tilden Produce Co., 265 U.S. 315; Miller vs. U.S., 294 U.S. 435.) As already stated, section 80 implements only section 30(c) of the Tax Code, or the provision allowing deduction of taxes, while herein respondent seeks to be allowed deduction under section 30(b), which provides for deduction of interest on indebtedness. In conclusion, we are of the opinion and so hold that although interest payment for delinquent taxes is not deductible as tax under Section 30(c) of the Tax Code and section 80 of the Income Tax Regulations, the taxpayer is not precluded thereby from claiming said interest payment as deduction under section 30(b) of the same Code. In view of the foregoing, the decision sought to be reviewed is affirmed, without pronouncement as to costs. Bengzon, Bautista Angelo, Labrador, Barrera, Paredes, and Dizon, JJ., concur. Paras, C. J., Concepcion, and Reyes, J.B.L., JJ., concur in the result.

CIR v. Lednicky, et al, Gitierrez v. Collector AMBOT

G.R. No. L-21551

September 30, 1969

FERNANDEZ HERMANOS, INC., petitioner, vs. COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE and COURT OF TAX APPEALS, respondents. -----------------------------

G.R. No. L-21557

September 30, 1969

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. FERNANDEZ HERMANOS, INC., and COURT OF TAX APPEALS, respondents. ----------------------------G.R. No. L-24972 September 30, 1969

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. FERNANDEZ HERMANOS INC., and the COURT OF TAX APPEALS, respondents. ----------------------------G.R. No. L-24978 September 30, 1969

FERNANDEZ HERMANOS, INC., petitioner, vs. THE COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, and HON. ROMAN A. UMALI, COURT OF TAX APPEALS, respondents. L-21551: Rafael Dinglasan for petitioner. Office of the Solicitor General Arturo A. Alafriz, Solicitor Alejandro B. Afurong and Special Attorney Virgilio G. Saldajeno for respondent. L-21557: Office of the Solicitor General for petitioner. Rafael Dinglasan for respondent Fernandez Hermanos, Inc. L-24972: Office of the Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo, Assistant Solicitor General Felicisimo R. Rosete and Special Attorney Virgilio G. Saldajeno for petitioner. Rafael Dinglasan for respondent Fernandez Hermanos, Inc. L-24978: Rafael Dinglasan for petitioner. Office of the Solicitor General Antonio P. Barredo, Assistant Solicitor General Antonio G. Ibarra and Special Attorney Virgilio G. Saldajeno for respondent.

TEEHANKEE, J.: These four appears involve two decisions of the Court of Tax Appeals determining the taxpayer's income tax liability for the years 1950 to 1954 and for the year 1957. Both the taxpayer and the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, as petitioner and respondent in the cases a quo respectively, appealed from the Tax Court's decisions, insofar as their respective contentions on particular tax items were therein resolved against them. Since the issues raised are interrelated, the Court resolves the four appeals in this joint decision. Cases L-21551 and L-21557 The taxpayer, Fernandez Hermanos, Inc., is a domestic corporation organized for the principal purpose of engaging in business as an "investment company" with main office at Manila. Upon verification of the taxpayer's income tax returns for the period in question, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue assessed against the taxpayer the sums of P13,414.00, P119,613.00, P11,698.00, P6,887.00 and P14,451.00 as alleged deficiency income taxes for the years 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953 and 1954, respectively. Said assessments were the result of alleged discrepancies found upon the examination and verification of the taxpayer's income tax returns for the said years, summarized by the Tax Court in its decision of June 10, 1963 in CTA Case No. 787, as follows: 1. Losses a. Losses in Mati Lumber Co. (1950) P 8,050.00

b. Losses in or bad debts of Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. (1951) 353,134.25 c. Losses in Balamban Coal Mines 1950 1951 8,989.76 27,732.66

d. Losses in Hacienda Dalupiri 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 17,418.95 29,125.82 26,744.81 21,932.62 42,938.56

e. Losses in Hacienda Samal

1951 1952

8,380.25 7,621.73

2. Excessive depreciation of Houses 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 P 8,180.40 8,768.11 18,002.16 13,655.25 29,314.98

3. Taxable increase in net worth 1950 1951 P 30,050.00 1,382.85 P 11,147.2611

4. Gain realized from sale of real property in 1950

The Tax Court sustained the Commissioner's disallowances of Item 1, sub-items (b) and (e) and Item 2 of the above summary, but overruled the Commissioner's disallowances of all the remaining items. It therefore modified the deficiency assessments accordingly, found the total deficiency income taxes due from the taxpayer for the years under review to amount to P123,436.00 instead of P166,063.00 as originally assessed by the Commissioner, and rendered the following judgment: RESUME 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 Total P2,748.00 108,724.00 3,600.00 2,501.00 5,863.00 P123,436.00

WHEREFORE, the decision appealed from is hereby modified, and petitioner is ordered to pay the sum of P123,436.00 within 30 days from the date this decision becomes final. If the said amount, or any part thereof, is not paid within said period, there shall be added to the unpaid amount as surcharge of 5%, plus interest as provided in Section 51 of the National Internal Revenue Code, as amended. With costs against petitioner. (Pp. 75, 76, Taxpayer's Brief as appellant)

Both parties have appealed from the respective adverse rulings against them in the Tax Court's decision. Two main issues are raised by the parties: first, the correctness of the Tax Court's rulings with respect to the disputed items of disallowances enumerated in the Tax Court's summary reproduced above, and second, whether or not the government's right to collect the deficiency income taxes in question has already prescribed. On the first issue, we will discuss the disputed items of disallowances seriatim. 1. Re allowances/disallowances of losses. (a) Allowance of losses in Mati Lumber Co. (1950). The Commissioner of Internal Revenue questions the Tax Court's allowance of the taxpayer's writing off as worthless securities in its 1950 return the sum of P8,050.00 representing the cost of shares of stock of Mati Lumber Co. acquired by the taxpayer on January 1, 1948, on the ground that the worthlessness of said stock in the year 1950 had not been clearly established. The Commissioner contends that although the said Company was no longer in operation in 1950, it still had its sawmill and equipment which must be of considerable value. The Court, however, found that "the company ceased operations in 1949 when its Manager and owner, a certain Mr. Rocamora, left for Spain ,where he subsequently died. When the company eased to operate, it had no assets, in other words, completely insolvent. This information as to the insolvency of the Company reached (the taxpayer) in 1950," when it properly claimed the loss as a deduction in its 1950 tax return, pursuant to Section 30(d) (4) (b) or Section 30 (e) (3) of the National Internal Revenue Code. 2 We find no reason to disturb this finding of the Tax Court. There was adequate basis for the writing off of the stock as worthless securities. Assuming that the Company would later somehow realize some proceeds from its sawmill and equipment, which were still existing as claimed by the Commissioner, and that such proceeds would later be distributed to its stockholders such as the taxpayer, the amount so received by the taxpayer would then properly be reportable as income of the taxpayer in the year it is received. (b) Disallowance of losses in or bad debts of Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. (1951). The taxpayer appeals from the Tax Court's disallowance of its writing off in 1951 as a loss or bad debt the sum of P353,134.25, which it had advanced or loaned to Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. The Tax Court's findings on this item follow: Sometime in 1945, Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., the controlling stockholders of which are also the controlling stockholders of petitioner corporation, requested financial help from petitioner to enable it to resume it mining operations in Coron, Palawan. The request for financial assistance was readily and unanimously approved by the Board of Directors of petitioner, and thereafter a memorandum agreement was executed on August 12, 1945, embodying the terms and conditions under which the financial assistance was to be extended, the pertinent provisions of which are as follows: "WHEREAS, the FIRST PARTY, by virtue of its resolution adopted on August 10, 1945, has agreed to extend to the SECOND PARTY the requested financial help by way of accommodation advances and for this purpose has

authorized its President, Mr. Ramon J. Fernandez to cause the release of funds to the SECOND PARTY. "WHEREAS, to compensate the FIRST PARTY for the advances that it has agreed to extend to the SECOND PARTY, the latter has agreed to pay to the former fifteen per centum (15%) of its net profits. "NOW THEREFORE, for and in consideration of the above premises, the parties hereto have agreed and covenanted that in consideration of the financial help to be extended by the FIRST PARTY to the SECOND PARTY to enable the latter to resume its mining operations in Coron, Palawan, the SECOND PARTY has agreed and undertaken as it hereby agrees and undertakes to pay to the FIRST PARTY fifteen per centum (15%) of its net profits." (Exh. H-2) Pursuant to the agreement mentioned above, petitioner gave to Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. yearly advances starting from 1945, which advances amounted to P587,308.07 by the end of 1951. Despite these advances and the resumption of operations by Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., it continued to suffer losses. By 1951, petitioner became convinced that those advances could no longer be recovered. While it continued to give advances, it decided to write off as worthless the sum of P353,134.25. This amount "was arrived at on the basis of the total of advances made from 1945 to 1949 in the sum of P438,981.39, from which amount the sum of P85,647.14 had to be deducted, the latter sum representing its pre-war assets. (t.s.n., pp. 136-139, Id)." (Page 4, Memorandum for Petitioner.) Petitioner decided to maintain the advances given in 1950 and 1951 in the hope that it might be able to recover the same, as in fact it continued to give advances up to 1952. From these facts, and as admitted by petitioner itself, Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., was still in operation when the advances corresponding to the years 1945 to 1949 were written off the books of petitioner. Under the circumstances, was the sum of P353,134.25 properly claimed by petitioner as deduction in its income tax return for 1951, either as losses or bad debts? It will be noted that in giving advances to Palawan Manganese Mine Inc., petitioner did not expect to be repaid. It is true that some testimonial evidence was presented to show that there was some agreement that the advances would be repaid, but no documentary evidence was presented to this effect. The memorandum agreement signed by the parties appears to be very clear that the consideration for the advances made by petitioner was 15% of the net profits of Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. In other words, if there were no earnings or profits, there was no obligation to repay those advances. It has been held that the voluntary advances made without expectation of repayment do not result in deductible losses. 1955 PH Fed. Taxes, Par. 13, 329, citing W. F. Young, Inc. v. Comm., 120 F 2d. 159, 27 AFTR 395; George B. Markle, 17 TC. 1593. Is the said amount deductible as a bad debt? As already stated, petitioner gave advances to Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., without expectation of repayment. Petitioner could not sue for recovery under the memorandum agreement because the obligation of Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. was to pay petitioner 15% of its net profits, not the advances. No bad debt could arise where there is no valid and subsisting debt.

Again, assuming that in this case there was a valid and subsisting debt and that the debtor was incapable of paying the debt in 1951, when petitioner wrote off the advances and deducted the amount in its return for said year, yet the debt is not deductible in 1951 as a worthless debt. It appears that the debtor was still in operation in 1951 and 1952, as petitioner continued to give advances in those years. It has been held that if the debtor corporation, although losing money or insolvent, was still operating at the end of the taxable year, the debt is not considered worthless and therefore not deductible. 3 The Tax Court's disallowance of the write-off was proper. The Solicitor General has rightly pointed out that the taxpayer has taken an "ambiguous position " and "has not definitely taken a stand on whether the amount involved is claimed as losses or as bad debts but insists that it is either a loss or a bad debt." 4 We sustain the government's position that the advances made by the taxpayer to its 100% subsidiary, Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. amounting to P587,308,07 as of 1951 were investments and not loans. 5 The evidence on record shows that the board of directors of the two companies since August, 1945, were identical and that the only capital of Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. is the amount of P100,000.00 entered in the taxpayer's balance sheet as its investment in its subsidiary company. 6 This fact explains the liberality with which the taxpayer made such large advances to the subsidiary, despite the latter's admittedly poor financial condition. The taxpayer's contention that its advances were loans to its subsidiary as against the Tax Court's finding that under their memorandum agreement, the taxpayer did not expect to be repaid, since if the subsidiary had no earnings, there was no obligation to repay those advances, becomes immaterial, in the light of our resolution of the question. The Tax Court correctly held that the subsidiary company was still in operation in 1951 and 1952 and the taxpayer continued to give it advances in those years, and, therefore, the alleged debt or investment could not properly be considered worthless and deductible in 1951, as claimed by the taxpayer. Furthermore, neither under Section 30 (d) (2) of our Tax Code providing for deduction by corporations of losses actually sustained and charged off during the taxable year nor under Section 30 (e) (1) thereof providing for deduction of bad debts actually ascertained to be worthless and charged off within the taxable year, can there be a partial writing off of a loss or bad debt, as was sought to be done here by the taxpayer. For such losses or bad debts must be ascertained to be so and written off during the taxable year, are therefore deductible in full or not at all, in the absence of any express provision in the Tax Code authorizing partial deductions. The Tax Court held that the taxpayer's loss of its investment in its subsidiary could not be deducted for the year 1951, as the subsidiary was still in operation in 1951 and 1952. The taxpayer, on the other hand, claims that its advances were irretrievably lost because of the staggering losses suffered by its subsidiary in 1951 and that its advances after 1949 were "only limited to the purpose of salvaging whatever ore was already available, and for the purpose of paying the wages of the laborers who needed help." 7 The correctness of the Tax Court's ruling in sustaining the disallowance of the write-off in 1951 of the taxpayer's claimed losses is borne out by subsequent events shown in Cases L-24972 and L-24978 involving the taxpayer's 1957 income tax liability. (Infra, paragraph 6.) It will there be seen that by 1956, the obligation of the taxpayer's subsidiary to it had been reduced from P587,398.97 in 1951 to P442,885.23 in 1956, and that it was only on January 1, 1956 that the subsidiary decided to cease operations. 8

(c) Disallowance of losses in Balamban Coal Mines (1950 and 1951). The Court sustains the Tax Court's disallowance of the sums of P8,989.76 and P27,732.66 spent by the taxpayer for the operation of its Balamban coal mines in Cebu in 1950 and 1951, respectively, and claimed as losses in the taxpayer's returns for said years. The Tax Court correctly held that the losses "are deductible in 1952, when the mines were abandoned, and not in 1950 and 1951, when they were still in operation." 9 The taxpayer's claim that these expeditions should be allowed as losses for the corresponding years that they were incurred, because it made no sales of coal during said years, since the promised road or outlet through which the coal could be transported from the mines to the provincial road was not constructed, cannot be sustained. Some definite event must fix the time when the loss is sustained, and here it was the event of actual abandonment of the mines in 1952. The Tax Court held that the losses, totalling P36,722.42 were properly deductible in 1952, but the appealed judgment does not show that the taxpayer was credited therefor in the determination of its tax liability for said year. This additional deduction of P36,722.42 from the taxpayer's taxable income in 1952 would result in the elimination of the deficiency tax liability for said year in the sum of P3,600.00 as determined by the Tax Court in the appealed judgment. (d) and (e) Allowance of losses in Hacienda Dalupiri (1950 to 1954) and Hacienda Samal (1951-1952). The Tax Court overruled the Commissioner's disallowance of these items of losses thus: Petitioner deducted losses in the operation of its Hacienda Dalupiri the sums of P17,418.95 in 1950, P29,125.82 in 1951, P26,744.81 in 1952, P21,932.62 in 1953, and P42,938.56 in 1954. These deductions were disallowed by respondent on the ground that the farm was operated solely for pleasure or as a hobby and not for profit. This conclusion is based on the fact that the farm was operated continuously at a loss.1awphl.nt From the evidence, we are convinced that the Hacienda Dalupiri was operated by petitioner for business and not pleasure. It was mainly a cattle farm, although a few race horses were also raised. It does not appear that the farm was used by petitioner for entertainment, social activities, or other non-business purposes. Therefore, it is entitled to deduct expenses and losses in connection with the operation of said farm. (See 1955 PH Fed. Taxes, Par. 13, 63, citing G.C.M. 21103, CB 1939-1, p.164) Section 100 of Revenue Regulations No. 2, otherwise known as the Income Tax Regulations, authorizes farmers to determine their gross income on the basis of inventories. Said regulations provide: "If gross income is ascertained by inventories, no deduction can be made for livestock or products lost during the year, whether purchased for resale, produced on the farm, as such losses will be reflected in the inventory by reducing the amount of livestock or products on hand at the close of the year." Evidently, petitioner determined its income or losses in the operation of said farm on the basis of inventories. We quote from the memorandum of counsel for petitioner:

"The Taxpayer deducted from its income tax returns for the years from 1950 to 1954 inclusive, the corresponding yearly losses sustained in the operation of Hacienda Dalupiri, which losses represent the excess of its yearly expenditures over the receipts; that is, the losses represent the difference between the sales of livestock and the actual cash disbursements or expenses." (Pages 21-22, Memorandum for Petitioner.) As the Hacienda Dalupiri was operated by petitioner for business and since it sustained losses in its operation, which losses were determined by means of inventories authorized under Section 100 of Revenue Regulations No. 2, it was error for respondent to have disallowed the deduction of said losses. The same is true with respect to loss sustained in the operation of the Hacienda Samal for the years 1951 and 1952. 10 The Commissioner questions that the losses sustained by the taxpayer were properly based on the inventory method of accounting. He concedes, however, "that the regulations referred to does not specify how the inventories are to be made. The Tax Court, however, felt satisfied with the evidence presented by the taxpayer ... which merely consisted of an alleged physical count of the number of the livestock in Hacienda Dalupiri for the years involved." 11 The Tax Court was satisfied with the method adopted by the taxpayer as a farmer breeding livestock, reporting on the basis of receipts and disbursements. We find no Compelling reason to disturb its findings. 2. Disallowance of excessive depreciation of buildings (1950-1954). During the years 1950 to 1954, the taxpayer claimed a depreciation allowance for its buildings at the annual rate of 10%. The Commissioner claimed that the reasonable depreciation rate is only 3% per annum, and, hence, disallowed as excessive the amount claimed as depreciation allowance in excess of 3% annually. We sustain the Tax Court's finding that the taxpayer did not submit adequate proof of the correctness of the taxpayer's claim that the depreciable assets or buildings in question had a useful life only of 10 years so as to justify its 10% depreciation per annum claim, such finding being supported by the record. The taxpayer's contention that it has many zero or one-peso assets, 12 representing very old and fully depreciated assets serves but to support the Commissioner's position that a 10% annual depreciation rate was excessive. 3. Taxable increase in net worth (1950-1951). The Tax Court set aside the Commissioner's treatment as taxable income of certain increases in the taxpayer's net worth. It found that: For the year 1950, respondent determined that petitioner had an increase in net worth in the sum of P30,050.00, and for the year 1951, the sum of P1,382.85. These amounts were treated by respondent as taxable income of petitioner for said years. It appears that petitioner had an account with the Manila Insurance Company, the records bearing on which were lost. When its records were reconstituted the amount of P349,800.00 was set up as its liability to the Manila Insurance Company. It was discovered later that the correct liability was only 319,750.00, or a difference of P30,050.00, so that the records were adjusted so as to show the correct liability. The correction or adjustment was made in 1950. Respondent contends that the reduction of

petitioner's liability to Manila Insurance Company resulted in the increase of petitioner's net worth to the extent of P30,050.00 which is taxable. This is erroneous. The principle underlying the taxability of an increase in the net worth of a taxpayer rests on the theory that such an increase in net worth, if unreported and not explained by the taxpayer, comes from income derived from a taxable source. (See Perez v. Araneta, G.R. No. L-9193, May 29, 1957; Coll. vs. Reyes, G.R. Nos. L- 11534 & L-11558, Nov. 25, 1958.) In this case, the increase in the net worth of petitioner for 1950 to the extent of P30,050.00 was not the result of the receipt by it of taxable income. It was merely the outcome of the correction of an error in the entry in its books relating to its indebtedness to the Manila Insurance Company. The Income Tax Law imposes a tax on income; it does not tax any or every increase in net worth whether or not derived from income. Surely, the said sum of P30,050.00 was not income to petitioner, and it was error for respondent to assess a deficiency income tax on said amount. The same holds true in the case of the alleged increase in net worth of petitioner for the year 1951 in the sum of P1,382.85. It appears that certain items (all amounting to P1,382.85) remained in petitioner's books as outstanding liabilities of trade creditors. These accounts were discovered in 1951 as having been paid in prior years, so that the necessary adjustments were made to correct the errors. If there was an increase in net worth of the petitioner, the increase in net worth was not the result of receipt by petitioner of taxable income." 13 The Commissioner advances no valid grounds in his brief for contesting the Tax Court's findings. Certainly, these increases in the taxpayer's net worth were not taxable increases in net worth, as they were not the result of the receipt by it of unreported or unexplained taxable income, but were shown to be merely the result of the correction of errors in its entries in its books relating to its indebtednesses to certain creditors, which had been erroneously overstated or listed as outstanding when they had in fact been duly paid. The Tax Court's action must be affirmed. 4. Gain realized from sale of real property (1950). We likewise sustain as being in accordance with the evidence the Tax Court's reversal of the Commissioner's assessment on all alleged unreported gain in the sum of P11,147.26 in the sale of a certain real property of the taxpayer in 1950. As found by the Tax Court, the evidence shows that this property was acquired in 1926 for P11,852.74, and was sold in 1950 for P60,000.00, apparently, resulting in a gain of P48,147.26. 14 The taxpayer reported in its return a gain of P37,000.00, or a discrepancy of P11,147.26. 15 It was sufficiently proved from the taxpayer's books that after acquiring the property, the taxpayer had made improvements totalling P11,147.26, 16 accounting for the apparent discrepancy in the reported gain. In other words, this figure added to the original acquisition cost of P11,852.74 results in a total cost of P23,000.00, and the gain derived from the sale of the property for P60,000.00 was correctly reported by the taxpayer at P37,000.00. On the second issue of prescription, the taxpayer's contention that the Commissioner's action to recover its tax liability should be deemed to have prescribed for failure on the part of the Commissioner to file a complaint for collection against it in an appropriate civil action, as contradistinguished from the answer filed by the Commissioner to its petition for review of the questioned assessments in the case a quo has long been rejected by this Court. This Court has consistently held that "a judicial action for the collection of a tax is begun by the filing of a complaint with the proper court of first instance, or where the assessment is appealed to the

Court of Tax Appeals, by filing an answer to the taxpayer's petition for review wherein payment of the tax is prayed for." 17 This is but logical for where the taxpayer avails of the right to appeal the tax assessment to the Court of Tax Appeals, the said Court is vested with the authority to pronounce judgment as to the taxpayer's liability to the exclusion of any other court. In the present case, regardless of whether the assessments were made on February 24 and 27, 1956, as claimed by the Commissioner, or on December 27, 1955 as claimed by the taxpayer, the government's right to collect the taxes due has clearly not prescribed, as the taxpayer's appeal or petition for review was filed with the Tax Court on May 4, 1960, with the Commissioner filing on May 20, 1960 his Answer with a prayer for payment of the taxes due, long before the expiration of the five-year period to effect collection by judicial action counted from the date of assessment. Cases L-24972 and L-24978 These cases refer to the taxpayer's income tax liability for the year 1957. Upon examination of its corresponding income tax return, the Commissioner assessed it for deficiency income tax in the amount of P38,918.76, computed as follows: Net income per return Add: Unallowable deductions: (1) Net loss claimed on Ha. Dalupiri (2) Amortization of Contractual right claimed as an expense under Mines Operations Net income per investigation Tax due thereon P29,178.70 89,547.33 48,481.62 P167,297.65 38,818.00

Less: Amount already assessed 5,836.00 Balance P32,982.00 Add: 1/2% monthly interest from 6-20-59 to 6-20-62 5,936.76 TOTAL AMOUNT DUE AND COLLECTIBLE P38,918.76

18

The Tax Court overruled the Commissioner's disallowance of the taxpayer's losses in the operation of its Hacienda Dalupiri in the sum of P89,547.33 but sustained the disallowance of the sum of P48,481.62, which allegedly represented 1/5 of the cost of the "contractual right" over the mines of its subsidiary, Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. which the taxpayer had acquired. It found the taxpayer liable for deficiency income tax for the year 1957 in the amount of P9,696.00, instead of P32,982.00 as originally assessed, and rendered the following judgment: WHEREFORE, the assessment appealed from is hereby modified. Petitioner is hereby ordered to pay to respondent the amount of P9,696.00 as deficiency income tax for the year 1957, plus the corresponding interest provided in Section 51 of the Revenue

Code. If the deficiency tax is not paid in full within thirty (30) days from the date this decision becomes final and executory, petitioner shall pay a surcharge of five per cent (5%) of the unpaid amount, plus interest at the rate of one per cent (1%) a month, computed from the date this decision becomes final until paid, provided that the maximum amount that may be collected as interest shall not exceed the amount corresponding to a period of three (3) years. Without pronouncement as to costs. 19 Both parties again appealed from the respective adverse rulings against them in the Tax Court's decision. 5. Allowance of losses in Hacienda Dalupiri (1957). The Tax Court cited its previous decision overruling the Commissioner's disallowance of losses suffered by the taxpayer in the operation of its Hacienda Dalupiri, since it was convinced that the hacienda was operated for business and not for pleasure. And in this appeal, the Commissioner cites his arguments in his appellant's brief in Case No. L-21557. The Tax Court, in setting aside the Commissioner's principal objections, which were directed to the accounting method used by the taxpayer found that: It is true that petitioner followed the cash basis method of reporting income and expenses in the operation of the Hacienda Dalupiri and used the accrual method with respect to its mine operations. This method of accounting, otherwise known as the hybrid method, followed by petitioner is not without justification. ... A taxpayer may not, ordinarily, combine the cash and accrual bases. The 1954 Code provisions permit, however, the use of a hybrid method of accounting, combining a cash and accrual method, under circumstances and requirements to be set out in Regulations to be issued. Also, if a taxpayer is engaged in more than one trade or business he may use a different method of accounting for each trade or business. And a taxpayer may report income from a business on accrual basis and his personal income on the cash basis.' (See Mertens, Law of Federal Income Taxation, Zimet & Stanley Revision, Vol. 2, Sec. 12.08, p. 26.) 20 The Tax Court, having satisfied itself with the adequacy of the taxpayer's accounting method and procedure as properly reflecting the taxpayer's income or losses, and the Commissioner having failed to show the contrary, we reiterate our ruling [supra, paragraph 1 (d) and (e)] that we find no compelling reason to disturb its findings. 6. Disallowance of amortization of alleged "contractual rights." The reasons for sustaining this disallowance are thus given by the Tax Court: It appears that the Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., during a special meeting of its Board of Directors on January 19, 1956, approved a resolution, the pertinent portions of which read as follows: "RESOLVED, as it is hereby resolved, that the corporation's current assets composed of ores, fuel, and oil, materials and supplies, spare parts and canteen

supplies appearing in the inventory and balance sheet of the Corporation as of December 31, 1955, with an aggregate value of P97,636.98, contractual rights for the operation of various mining claims in Palawan with a value of P100,000.00, its title on various mining claims in Palawan with a value of P142,408.10 or a total value of P340,045.02 be, as they are hereby ceded and transferred to Fernandez Hermanos, Inc., as partial settlement of the indebtedness of the corporation to said Fernandez Hermanos Inc. in the amount of P442,895.23." (Exh. E, p. 17, CTA rec.) On March 29, 1956, petitioner's corporation accepted the above offer of transfer, thus: "WHEREAS, the Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc., due to its yearly substantial losses has decided to cease operation on January 1, 1956 and in order to satisfy at least a part of its indebtedness to the Corporation, it has proposed to transfer its current assets in the amount of NINETY SEVEN THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED THIRTY SIX PESOS & 98/100 (P97,636.98) as per its balance sheet as of December 31, 1955, its contractual rights valued at ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND PESOS (P100,000.00) and its title over various mining claims valued at ONE HUNDRED FORTY TWO THOUSAND FOUR HUNDRED EIGHT PESOS & 10/100 (P142,408.10) or a total evaluation of THREE HUNDRED FORTY THOUSAND FORTY FIVE PESOS & 08/100 (P340,045.08) which shall be applied in partial settlement of its obligation to the Corporation in the amount of FOUR HUNDRED FORTY TWO THOUSAND EIGHT HUNDRED EIGHTY FIVE PESOS & 23/100 (P442,885.23)," (Exh. E-1, p. 18, CTA rec.) Petitioner determined the cost of the mines at P242,408.10 by adding the value of the contractual rights (P100,000.00) and the value of its mining claims (P142,408.10). Respondent disallowed the deduction on the following grounds: (1) that the Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. could not transfer P242,408.10 worth of assets to petitioner because the balance sheet of the said corporation for 1955 shows that it had only current as worth P97,636.96; and (2) that the alleged amortization of "contractual rights" is not allowed by the Revenue Code. The law in point is Section 30(g) (1) (B) of the Revenue Code, before its amendment by Republic Act No. 2698, which provided in part: "(g) Depletion of oil and gas wells and mines.: "(1) In general. ... (B) in the case of mines, a reasonable allowance for depletion thereof not to exceed the market value in the mine of the product thereof, which has been mined and sold during the year for which the return and computation are made. The allowances shall be made under rules and regulations to be prescribed by the Secretary of Finance: Provided, That when the allowances shall equal the capital invested, ... no further allowance shall be made."

Assuming, arguendo, that the Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. had assets worth P242,408.10 which it actually transferred to the petitioner in 1956, the latter cannot just deduct one-fifth (1/5) of said amount from its gross income for the year 1957 because such deduction in the form of depletion charge was not sanctioned by Section 30(g) (1) (B) of the Revenue Code, as above-quoted. xxx xxx xxx

The sole basis of petitioner in claiming the amount of P48,481.62 as a deduction was the memorandum of its mining engineer (Exh. 1, pp. 31-32, CTA rec.), who stated that the ore reserves of the Busuange Mines (Mines transferred by the Palawan Manganese Mines, Inc. to the petitioner) would be exhausted in five (5) years, hence, the claim for P48,481.62 or one-fifth (1/5) of the alleged cost of the mines corresponding to the year 1957 and every year thereafter for a period of 5 years. The said memorandum merely showed the estimated ore reserves of the mines and it probable selling price. No evidence whatsoever was presented to show the produced mine and for how much they were sold during the year for which the return and computation were made. This is necessary in order to determine the amount of depletion that can be legally deducted from petitioner's gross income. The method employed by petitioner in making an outright deduction of 1/5 of the cost of the mines is not authorized under Section 30(g) (1) (B) of the Revenue Code. Respondent's disallowance of the alleged "contractual rights" amounting to P48,481.62 must therefore be sustained. 21 The taxpayer insists in this appeal that it could use as a method for depletion under the pertinent provision of the Tax Code its "capital investment," representing the alleged value of its contractual rights and titles to mining claims in the sum of P242,408.10 and thus deduct outright one-fifth (1/5) of this "capital investment" every year. regardless of whether it had actually mined the product and sold the products. The very authorities cited in its brief give the correct concept of depletion charges that they "allow for the exhaustion of the capital value of the deposits by production"; thus, "as the cost of the raw materials must be deducted from the gross income before the net income can be determined, so the estimated cost of the reserve used up is allowed." 22 The alleged "capital investment" method invoked by the taxpayer is not a method of depletion, but the Tax Code provision, prior to its amendment by Section 1, of Republic Act No. 2698, which took effect on June 18, 1960, expressly provided that "when the allowances shall equal the capital invested ... no further allowances shall be made;" in other words, the "capital investment" was but the limitation of the amount of depletion that could be claimed. The outright deduction by the taxpayer of 1/5 of the cost of the mines, as if it were a "straight line" rate of depreciation, was correctly held by the Tax Court not to be authorized by the Tax Code. ACCORDINGLY, the judgment of the Court of Tax Appeals, subject of the appeals in Cases Nos. L-21551 and L-21557, as modified by the crediting of the losses of P36,722.42 disallowed in 1951 and 1952 to the taxpayer for the year 1953 as directed in paragraph 1 (c) of this decision, is hereby affirmed. The judgment of the Court of Tax Appeals appealed from in Cases Nos. L-24972 and L-24978 is affirmed in toto. No costs. So ordered.

Concepcion, C.J., Dizon, Makalintal, Zaldivar, Sanchez, Castro, Fernando, Capistrano and Barredo, JJ., concur.

G.R. No. L-22265

December 22, 1967

COLLECTOR OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner, vs. GOODRICH INTERNATIONAL RUBBER CO., respondent. Manuel O. Chan for respondent. Manuel O. Chan for respondent. CONCEPCION, C.J.: Appeal by the Government from a decision of the Court of Tax Appeals, setting aside the assessments made by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, in the sums of P14,128.00 and P8,439.00, as deficiency income taxes allegedly due from respondent Goodrich International Rubber Company hereinafter referred to as Goodrich for the years 1951 and 1952, respectively. These assessments were based on disallowed deductions, claimed by Goodrich, consisting of several alleged bad debts, in the aggregate sum of P50,455.41, for the year 1951, and the sum of P30,138.88, as representation expenses allegedly incurred in the year 1952. Goodrich had appealed from said assessments to the Court of Tax Appeals, which, after appropriate proceedings, rendered, on June 8, 1963, a decision allowing the deduction for bad debts, but disallowing the alleged representation expenses. On motion for reconsideration and new trial, filed by Goodrich, on November 19, 1963, the Court of Tax Appeals amended its aforementioned decision and allowed said deductions for representation expenses. Hence, this appeal by the Government. The alleged representation expenses are: 1. Expenses at Elks Club 2. Manila Polo Club 3. Army and Navy Club 4. Manila Golf Club 5. Wack Wack Golf Club, Casino Espaol, etc. TOTAL P10,959.21 4,947.35 2,812.95 4,478.45 6,940.92 P30,138.88

The claim for deduction thereof is based upon receipts issued, not by the entities in which the alleged expenses had been incurred, but by the officers of Goodrich who allegedly paid them. The claim must be rejected. If the expenses had really been incurred, receipts or chits would have been issued by the entities to which the payments had been made, and it would have been easy for Goodrich or its officers to produce such receipts.lawphil These issued by said officers merely attest to their claim that they had incurred and paid said expenses. They do not establish payment of said alleged expenses to the entities in which the same are said to have been incurred. The Court of Tax Appeals erred, therefore, in allowing the deduction thereof. The alleged bad debts are: 1. Portillo's Auto Seat Cover 2. Visayan Rapid Transit 3. Bataan Auto Seat Cover 4. Tres Amigos Auto Supply 5. P. C. Teodorolawphil 6. Ordnance Service, P.A. 7. Ordnance Service, P.C. 8. National land Settlement Administration 9. National Coconut Corporation 10. Interior Caltex Service Station 11. San Juan Auto Supply 12. P A C S A 13. Philippine Naval Patrol 14. Surplus Property Commission 15. Alverez Auto Supply 16. Lion Shoe Store 17. Ruiz Highway Transit 18. Esquire Auto Seat Cover TOTAL P630.31 17,810.26 373.13 1,370.31 650.00 386.42 796.26 3,020.76 644.74 1,505.87 4,530.64 45.36 14.18 277.68 285.62 1,686.93 2,350.00 3,536.94 P50,455.41*

The issue, in connection with these debts is whether or not the same had been properly deducted as bad debts for the year 1951. In this connection, we find: Portillo's Auto Seat Cover (P730.00): This debt was incurred in 1950. In 1951, the debtor paid P70.00, leaving a balance of P630.31. That same year, the account was written off as bad debt (Exhibit 3-C-4). Counsel for Goodrich had merely sent two (2) letters of demand in 1951 (Exh. B-14). In 1952, the debtor paid the full balance (Exhibit A). Visayan Rapid Transit (P17,810.26): This debt was, also, incurred in 1950. In 1951, it was charged off as bad debt, after the debtor had paid P275.21. No other payment had been made.lawphil Taxpayer's Accountant testified that, according to its branch manager in Cebu, he had been unable to collect the balance. The debtor had merely promised and kept on promising to pay. Taxpayer's counsel stated that the debtor had gone out of business and became insolvent, but no proof to this effect. was introduced. Bataan Auto Seat Cover (P373.13): This is the balance of a debt of P474.13 contracted in 1949. In 1951, the debtor paid P100.00. That same year, the balance of P373.13 was charged off as bad debt. The next year, the debtor paid the additional sum of P50.00. Tres Amigos Auto Supply (P1,370.31): This account had been outstanding since 1949. Counsel for the taxpayer had merely sent demand letters (Exh. B-13) without success. P. C. Teodoro (P650.00): In 1949, the account was P751.91. In 1951, the debtor paid P101.91, thus leaving a balance of P650.00, which the taxpayer charged off as bad debt in the same year. In 1952, the debtor made another payment of P150.00. Ordinance Service, P.A. (P386.42): In 1949, the outstanding account of this government agency was P817.55. Goodrich's counsel sent demand letters (Exh. B-8). In 1951, it paid Goodrich P431.13. The balance of P386.42 was written off as bad debt that same year. Ordinance Service, P.C. (P796.26): In 1950, the account was P796.26.lawphil It was referred to counsel for collection. In 1951, the account was written off as a debt. In 1952, the debtor paid it in full.