Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ah Thian V Government of Mal

Uploaded by

MoganaJSOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ah Thian V Government of Mal

Uploaded by

MoganaJSCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1

3 of 250 DOCUMENTS

2003 LexisNexis Asia (a division of Reed Elsevier (S) Pte Ltd)

The Malayan Law Journal

AH THIAN V GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA

[1976] 2 MLJ 112

FEDERAL COURT CRIMINAL APPLICATION NO 3 OF 1976

FC KUALA LUMPUR

DECIDED-DATE-1: 28 MAY 1976

SUFFIAN LP

CATCHWORDS:

Constitutional Law - Application to declare law invalid on ground of inconsistency with Constitution - Power may

be exercised by any court - Leave of Federal Court not necessary - Federal Constitution, arts 4, 8, 74 or 75

Constitutional Law - Parliament - Doctrine of supremacy of - Whether applicable in Malaysia

HEADNOTES:

In this case the applicant had been charged with committing armed gang robbery under sections 392 and 397 of the

Penal Code, an offence punishable under section 5 of the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act, 1971 as amended. It was

argued that the Firearms (Increased Penalties) (Amendment) Act, 1974 was ultra vires the Federal Constitution as it

contravened Article 8(1) of the Constitution and was therefore void. An adjournment was obtained to enable the

applicant to obtain the leave of a judge of the Federal Court to start proceedings for a declaration that the Act was void

for the reason stated.

Held: as the argument of the applicant was that the Act was invalid because it was inconsistent with the

Constitution, Clause (4) of Article 4 and Clause (1) of Article 128 of the Constitution did not apply and the point may

be raised in the ordinary way in the course of submission and determined in the High Court, without reference to the

Federal Court and there is no need for leave of a Judge of the Federal Court.

Case referred to

Ooi Ah Phua v OCCID Kedah/Perlis [1975] 2 MLJ 198

FEDERAL COURT

Karpal Singh for the applicant.

TS Nathan (Deputy Public Prosecutor) for the respondent.

ACTION: FEDERAL COURT

Page 2

LAWYERS: Karpal Singh for the applicant.

TS Nathan (Deputy Public Prosecutor) for the respondent.

JUDGMENTBY: SUFFIAN LP

This application is before me in my capacity as a judge of the Federal Court.

The applicant was charged with committing armed robbery under sections 392 and 397 of the Penal Code, an

offence punishable under section 5 of the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act 37 of 1971 as amended.

If convicted he is liable to imprisonment for his natural life and with whipping with no less than six strokes.

Also charged with him was one Ooi Chooi Toh who figured in the case of Ooi Ah Phua v OCCID Kedah/Perlis

[1975] 2 MLJ 198.

The applicant's counsel argued that the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act 37 of 1971 as amended by the Firearms

(Increased Penalties) (Amendment) Act A256 of 1974 is " ultra vires the Federal Constitution as it contravenes article

8(1) of the Constitution and is therefore void".

Article 8(1) reads-"All persons are equal before the law and entitled to the equal

protection of the law."

On March 30, 1976, at the close of the case for the prosecution, counsel for the applicant applied for an

adjournment to enable him to obtain the leave of a judge of the Federal Court to start proceedings for a declaration that

the Act is void for the reason already stated. The application was granted, hence this [*113] application before me. It is

said that the application is made under article 4(4) of the Constitution.

The doctrine of the supremacy of Parliament does not apply in Malaysia. Here we have a written constitution. The

power of Parliament and of State legislatures in Malaysia is limited by the Constitution, and they cannot make any law

they please.

Under our Constitution written law may be invalid on one of these grounds:

(1) in the case of Federal written law, because it relates to a matter

with respect to which Parliament has no power to make law, and in the case of

State written law, because it relates to a matter which respect to which the

State legislature has no power to make law, article 74; or

(2) in the case of both Federal and State written law, because it is

inconsistent with the Constitution, see article 4(1); or

(3) in the case of State written law, because it is inconsistent with

Federal law, article 75.

The court has power to declare any Federal or State law invalid on any of the above three grounds.

The court's power to declare any law invalid on grounds (2) and (3) is not subject to any restrictions, and may be

exercised by any court in the land and in any proceeding whether it be started by Government or by an individual.

But the power to declare any law invalid on ground (1) is subject to three restrictions prescribed by the

Constitution.

First, clause (3) of article 4 provides that the validity of any law made by Parliament or by a State legislature may

not be questioned on the ground that it makes provision with respect to any matter with respect to which the relevant

legislature has no power to make law, except in three types of proceedings as follows:-(a) in proceedings for a declaration that the law is invalid on that

ground; or

(b) if the law was made by Parliament, in proceedings between the

Federation and one or more states; or

(c) if the law was made by a State legislature, in proceedings between the

Federation and that State.

Page 3

It will be noted that proceedings of types (b) and (c) are brought by Government, and there is no need for any one

to ask specifically for a declaration that the law is invalid on the ground that it relates to a matter with respect to which

the relevant legislature has no power to make law. The point can be raised in the course of submission in the ordinary

way. Proceedings of type (a) may however be brought by an individual against another individual or against

Government or by Government against an individual, but whoever brings the proceedings must specifically ask for a

declaration that the law impugned is invalid on that ground.

Secondly, clause (4) of article 4 provides that proceedings of the type mentioned in (a) above may not be

commenced by an individual without leave of a judge of the Federal Court and the Federation is entitled to be a party to

such proceedings, and so is any State that would or might be a party to proceedings brought for the same purpose under

type (b) or (c) above. This is to ensure that no adverse ruling is made without giving the relevant government an

opportunity to argue to the contrary.

Thirdly, clause (1) of article 128 provides that only the Federal Court has jurisdiction to determine whether a law

made by Parliament or by a State legislature is invalid on the ground that it relates to a matter with respect to which the

relevant legislature has no power to make law. This jurisdiction is exclusive to the Federal Court, no other court has it.

This is to ensure that a law may be declared invalid on this very serious ground only after full consideration by the

highest court in the land.

The applicant wants to attack the validity of the Firearms (Increased Penalties) Act not on the ground that it relates

to a matter with respect to which Parliament has no power to make law. In my judgment, this Act deals with criminal

law and the administration of justice, both matters with respect to which Parliament has power to make law (see item 4

of List I in the Ninth Schedule to the Constitution). The applicant says that the Act is invalid because it is inconsistent

with the Constitution, i.e. on ground (2) set out in paragraph 9 above. Therefore clause (4) of article 4 and clause (1) of

article 128 do not apply and the point may be raised in the ordinary way in the course of submission, and determined in

the High Court, without reference to the Federal Court, and there is no need for leave of a judge of the Federal Court.

True the learned judge has power under section 48 of the Courts of Judicature Act, 1964 (L.M. Act 91) to stay the

proceedings before him and refer a matter like this to the Federal Court. He has not however done so in this case (this is

an application by the accused). But in any event matters like this as a matter of convenience and to save the parties time

and expense are best dealt with by him in the ordinary way, and the aggrieved party should be left to appeal in the

ordinary way to the Federal Court.

If the learned judge had done that here, the applicant and his co-accused would have been acquitted or convicted by

now. As it is, in 1976 they are still being tried for an offence which they are alleged to have committed on December

26, 1974.

My order on the application is that this matter be remitted back for continuation of trial by the High Court.

Order accordingly.

SOLICITORS:

Solicitors: Karpal Singh & Co

LOAD-DATE: June 3, 2003

You might also like

- Ah Thian V Government of Malaysia - (1976) 2Document3 pagesAh Thian V Government of Malaysia - (1976) 2Saravanan Muniandy100% (1)

- Ah Thian V Government of MalaysiaDocument7 pagesAh Thian V Government of MalaysiaRobin WongNo ratings yet

- Governor's power to dismiss CMDocument13 pagesGovernor's power to dismiss CMKyriosHaiqalNo ratings yet

- United Asian BankDocument11 pagesUnited Asian BankIzzat MdnorNo ratings yet

- (CA) (1997) 1 CLJ 665 - Hong Leong Equipment Sdn. Bhd. V Liew Fook Chuan & Other AppealsDocument94 pages(CA) (1997) 1 CLJ 665 - Hong Leong Equipment Sdn. Bhd. V Liew Fook Chuan & Other AppealsAlae Kiefer100% (2)

- Land Acquisition Case for Hockey StadiumDocument17 pagesLand Acquisition Case for Hockey StadiumFlona LowNo ratings yet

- Interpreting "Save in Accordance with LawDocument125 pagesInterpreting "Save in Accordance with LawLuqman Hakeem100% (1)

- PP V Khong Teng KhenDocument3 pagesPP V Khong Teng Khenian_ling_2No ratings yet

- Malayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseDocument22 pagesMalayan Law Journal Reports 1995 Volume 3 CaseChin Kuen YeiNo ratings yet

- Tan Hee JuanDocument4 pagesTan Hee JuanChin Kuen YeiNo ratings yet

- MBL Indiv - AssgmntDocument2 pagesMBL Indiv - AssgmntNurulhuda HanasNo ratings yet

- Lockup Rules 1953Document8 pagesLockup Rules 1953Wong Xinyan100% (1)

- Bank Bumiputra Malaysia BHD & Anor V Lorrain Osman & Ors (1985) 2 MLJ 236Document10 pagesBank Bumiputra Malaysia BHD & Anor V Lorrain Osman & Ors (1985) 2 MLJ 236sitifatimahabdulwahidNo ratings yet

- Summary Dato JagindarDocument2 pagesSummary Dato Jagindarlaiyyeen75% (8)

- TOPIC 1 - Sale of GoodsDocument49 pagesTOPIC 1 - Sale of GoodsnisaNo ratings yet

- Mohd. Latiff Bin Shah Mohd. & 2 Ors. v. Tengku Abdullah Ibni Sultan Abu Bakar & 8 Ors. & 2 Other CasesDocument25 pagesMohd. Latiff Bin Shah Mohd. & 2 Ors. v. Tengku Abdullah Ibni Sultan Abu Bakar & 8 Ors. & 2 Other CasesWai Chong KhuanNo ratings yet

- Soon Singh Bikar v. Perkim Kedah & AnorDocument18 pagesSoon Singh Bikar v. Perkim Kedah & AnorIeyza AzmiNo ratings yet

- Glul 2023 Business LOW: Section 136, Contract Act Section 137, Contract ActDocument18 pagesGlul 2023 Business LOW: Section 136, Contract Act Section 137, Contract Actzarfarie aron100% (3)

- Recovering money or property from illegal contracts under Section 66Document3 pagesRecovering money or property from illegal contracts under Section 66Hermosa Arof100% (1)

- Case Summary - T.sivamDocument2 pagesCase Summary - T.sivamKaren Tan100% (1)

- Islamic Family Law in MalaysiaDocument13 pagesIslamic Family Law in MalaysiaMuhammad Syafiq Yadiy0% (1)

- Local Limits of JurisdictionDocument2 pagesLocal Limits of JurisdictionTeebaSolaimalaiNo ratings yet

- Datuk Jagindar Singh & Ors V Tara RajaratnamDocument19 pagesDatuk Jagindar Singh & Ors V Tara Rajaratnamemilakbar93% (14)

- Cheng Keng Hong V Govt of The Federation of Malaya (1966)Document3 pagesCheng Keng Hong V Govt of The Federation of Malaya (1966)Afdhallan syafiqNo ratings yet

- Division of Matrimonial Assets Case AnalaysisDocument5 pagesDivision of Matrimonial Assets Case AnalaysisElaineSaw100% (1)

- Lecture 9 Hire Purchase LawDocument31 pagesLecture 9 Hire Purchase LawSyarah Syazwan SaturyNo ratings yet

- Undue Influence Malaysia PositionDocument8 pagesUndue Influence Malaysia PositionChina Wei100% (9)

- KP Kunchi Raman V Goh Brothers SDN BHDDocument2 pagesKP Kunchi Raman V Goh Brothers SDN BHDNelfi Amiera Mizan50% (4)

- LEHA BINTE JUSOH V AWANG JOHORI 1978 .DocherhDocument2 pagesLEHA BINTE JUSOH V AWANG JOHORI 1978 .DocherhMinNie Yee100% (4)

- Answer For Law of ContractDocument4 pagesAnswer For Law of ContractAzhari Ahmad50% (2)

- Law 309 Individual AssignmentDocument6 pagesLaw 309 Individual AssignmentNur IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Wan Salimah Wan Jaffar v. Mahmood Omar Anim Abdul Aziz (Intervener)Document35 pagesWan Salimah Wan Jaffar v. Mahmood Omar Anim Abdul Aziz (Intervener)Amira NadhirahNo ratings yet

- Shahamin Faizul Kung Abdullah v. Asma HJ JunusDocument8 pagesShahamin Faizul Kung Abdullah v. Asma HJ JunusIeyza AzmiNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law Assignment ChallengedDocument5 pagesAdministrative Law Assignment ChallengedAmir Zahin AzhamNo ratings yet

- S206 (3) National Land CodeDocument25 pagesS206 (3) National Land CodeCarmel Grace PhilipNo ratings yet

- Agreement Between Two or More Parties That Is Legally Binding Between ThemDocument10 pagesAgreement Between Two or More Parties That Is Legally Binding Between ThemNoor Salehah60% (5)

- Malaysian Finance Company Default Judgment Set AsideDocument12 pagesMalaysian Finance Company Default Judgment Set AsideSeng Wee TohNo ratings yet

- Mohd Faizal Musa V. Menteri Keselamatan Dalam NegeriDocument21 pagesMohd Faizal Musa V. Menteri Keselamatan Dalam NegeriTheCarnation19100% (1)

- East Union Malaysia V Gov of Johor & MalaysiaDocument2 pagesEast Union Malaysia V Gov of Johor & MalaysiaMiauGoddessNo ratings yet

- DATUK HAJI HARUN BIN HAJI IDRIS v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR - Land Approval Corruption CaseDocument43 pagesDATUK HAJI HARUN BIN HAJI IDRIS v PUBLIC PROSECUTOR - Land Approval Corruption CaseSuhail Abdul Halim67% (3)

- The Strengths and Weakness Federation of MalaysianDocument11 pagesThe Strengths and Weakness Federation of MalaysianZian Douglas0% (2)

- Tutorial 1Document1 pageTutorial 1Nerissa ZahirNo ratings yet

- CLJ 1996 1 393 Unisza1 PDFDocument36 pagesCLJ 1996 1 393 Unisza1 PDFDhabitah AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice Sample of Tutorial AnswerDocument5 pagesProfessional Practice Sample of Tutorial AnswerElaineSawNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Tutorial Question On Promissory EstoppelDocument13 pagesPresentation On Tutorial Question On Promissory EstoppelNaqeeb NexerNo ratings yet

- Malayan Law Journal Unreported decision on negligence and breach of contract claimsDocument11 pagesMalayan Law Journal Unreported decision on negligence and breach of contract claimsKaren TanNo ratings yet

- Kheng Chwee Lian Vs Wong Tak ThongDocument1 pageKheng Chwee Lian Vs Wong Tak ThongPauline Pao LienNo ratings yet

- HSBC Bank Malaysia BHD (Formerly Known As HoDocument18 pagesHSBC Bank Malaysia BHD (Formerly Known As Hof.dnNo ratings yet

- FED CONST BASIC FEATURESDocument6 pagesFED CONST BASIC FEATURESChe Nur HasikinNo ratings yet

- Contract II Assignment - Final QuesDocument35 pagesContract II Assignment - Final QuessyahindahNo ratings yet

- MPPP V Boey Siew ThanDocument9 pagesMPPP V Boey Siew ThanKeroppi GreenNo ratings yet

- Definitions:: Harta SepencarianDocument4 pagesDefinitions:: Harta SepencarianLina ZainalNo ratings yet

- Cases ListDocument1 pageCases ListAnonymous tzWYRWg02No ratings yet

- Cases On PupilsDocument4 pagesCases On PupilsSyarah Syazwan SaturyNo ratings yet

- Hebeas Corpus in MalaysiaDocument28 pagesHebeas Corpus in MalaysiaInaz Id100% (9)

- Assignment Law Q 26, 48, 78Document13 pagesAssignment Law Q 26, 48, 78Syahirah AliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 AcceptanceDocument10 pagesChapter 2 AcceptanceR JonNo ratings yet

- AH THIAN v. GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIADocument5 pagesAH THIAN v. GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIAhidayahNo ratings yet

- Ans Tut Week 6Document4 pagesAns Tut Week 6Harini ArichandranNo ratings yet

- Mohamaed Habibullah Mahmood v Faridah Dato Talib 2 MLJ 793: Case on domestic violence and jurisdiction of Syariah CourtDocument35 pagesMohamaed Habibullah Mahmood v Faridah Dato Talib 2 MLJ 793: Case on domestic violence and jurisdiction of Syariah CourtIrah LokmanNo ratings yet

- Elementary School: Cash Disbursements RegisterDocument1 pageElementary School: Cash Disbursements RegisterRonilo DagumampanNo ratings yet

- An Overview of National Ai Strategies and Policies © Oecd 2021Document26 pagesAn Overview of National Ai Strategies and Policies © Oecd 2021wanyama DenisNo ratings yet

- Geneva IntrotoBankDebt172Document66 pagesGeneva IntrotoBankDebt172satishlad1288No ratings yet

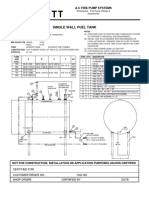

- Single Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump SystemsDocument1 pageSingle Wall Fuel Tank: FP 2.7 A-C Fire Pump Systemsricardo cardosoNo ratings yet

- Mayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechDocument19 pagesMayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechMichael McAndrewNo ratings yet

- An4856 Stevalisa172v2 2 KW Fully Digital Ac DC Power Supply Dsmps Evaluation Board StmicroelectronicsDocument74 pagesAn4856 Stevalisa172v2 2 KW Fully Digital Ac DC Power Supply Dsmps Evaluation Board StmicroelectronicsStefano SalaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Document1 pagePeople vs. Ulip, G.R. No. L-3455Grace GomezNo ratings yet

- Open Compute Project AMD Motherboard Roadrunner 2.1 PDFDocument36 pagesOpen Compute Project AMD Motherboard Roadrunner 2.1 PDFakok22No ratings yet

- SD Electrolux LT 4 Partisi 21082023Document3 pagesSD Electrolux LT 4 Partisi 21082023hanifahNo ratings yet

- Continuation in Auditing OverviewDocument21 pagesContinuation in Auditing OverviewJayNo ratings yet

- Supplier Quality Requirement Form (SSQRF) : Inspection NotificationDocument1 pageSupplier Quality Requirement Form (SSQRF) : Inspection Notificationsonnu151No ratings yet

- Ata 36 PDFDocument149 pagesAta 36 PDFAyan Acharya100% (2)

- SAP PS Step by Step OverviewDocument11 pagesSAP PS Step by Step Overviewanand.kumarNo ratings yet

- WitepsolDocument21 pagesWitepsolAnastasius HendrianNo ratings yet

- Laundry & Home Care: Key Financials 1Document1 pageLaundry & Home Care: Key Financials 1Catrinoiu PetreNo ratings yet

- FEM Lecture Notes-2Document18 pagesFEM Lecture Notes-2macynthia26No ratings yet

- Novirost Sample TeaserDocument2 pagesNovirost Sample TeaserVlatko KotevskiNo ratings yet

- New Installation Procedures - 2Document156 pagesNew Installation Procedures - 2w00kkk100% (2)

- Academy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapDocument1 pageAcademy Broadcasting Services Managerial MapAnthony WinklesonNo ratings yet

- COVID-19's Impact on Business PresentationsDocument2 pagesCOVID-19's Impact on Business PresentationsRetmo NandoNo ratings yet

- For Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierDocument4 pagesFor Mail Purpose Performa For Reg of SupplierAkshya ShreeNo ratings yet

- Logistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSDocument20 pagesLogistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSJenishNo ratings yet

- (SIRI Assessor Training) AM Guide Book - v2Document19 pages(SIRI Assessor Training) AM Guide Book - v2hadeelNo ratings yet

- Module 5Document10 pagesModule 5kero keropiNo ratings yet

- Comparing Time Series Models to Predict Future COVID-19 CasesDocument31 pagesComparing Time Series Models to Predict Future COVID-19 CasesManoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Royal Enfield Market PositioningDocument7 pagesRoyal Enfield Market PositioningApoorv Agrawal67% (3)

- Lister LRM & SRM 1-2-3 Manual and Parts List - Lister - Canal WorldDocument4 pagesLister LRM & SRM 1-2-3 Manual and Parts List - Lister - Canal Worldcountry boyNo ratings yet

- Programme Report Light The SparkDocument17 pagesProgramme Report Light The SparkAbhishek Mishra100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty in Big BasketDocument73 pagesCustomer Satisfaction and Brand Loyalty in Big BasketUpadhayayAnkurNo ratings yet

- Discretionary Lending Power Updated Sep 2012Document28 pagesDiscretionary Lending Power Updated Sep 2012akranjan888No ratings yet