Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wyden Speech at Wayne Morse Legacy Series

Uploaded by

Senator Ron WydenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wyden Speech at Wayne Morse Legacy Series

Uploaded by

Senator Ron WydenCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Picking Up the Morse Tradition: Taking on Excessive National Security Secrecy and Asking the Tough Questions As prepared for delivery More than sixty years ago, Wayne Morse took a folding chair not unlike the kind most of us have in our homes down to the Senate floor. Now, if youve never seen the Senate floor, its an ornate space filled with a hundred old wooden desks - one for each senator. The desks, though immaculately maintained, all contain carvings on the inside of the names of senators who have held that seat in the past. Its a historic room befitting one of the worlds oldest deliberative bodies. Suffice it to say, a folding chair didnt quite fit in. As the story goes, on this particular day, Senator Morse was not sitting at his desk. Instead, he unfolded that chair in the aisle dividing the two parties, sat down and refused to move. To add some context, Morse had just recently left the Republican party in protest of General Eisenhowers decision to choose Richard Nixon as his running mate. He had not yet joined the Democratic party; that would not happen for another few years. He was technically an independent, neither aligned with the Republicans nor the Democrats. He was a man without a party so he sat like one -- independently. It was a gesture of principle above politics and above party. It was Wayne Morse through and through.

I have the honor to be the current tenant of the seat Senator Morse once held. And because of that I feel I have the duty to maintain that very same spirit of principle and independence. As some of you know, I am a journalists son. Much of my youth was spent chasing the delusional dream of playing in the NBA while my father travelled from town to town taking jobs with newspapers and magazines. He researched and wrote books but most importantly, he asked questions. To me, one of the most important functions a legislator can perform is to ask tough questions on the publics behalf to inform the public and serve as a check on the executive branch. And that was definitely Senator Morses view. I have been invited today to talk about the surveillance state and its impact on the rights and civil liberties of Americans. If youll indulge me, Id also like to talk about my history with Senator Morse and how some of the seminal moments of his career have affected my own thinking. As I do I hope youll come to see that much of Senator Morses battle against excessive national security secrecy resonates in todays interactions between Congress and the Executive Branch. Senator Morse didnt live to see the creation of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, I am positive that he would agree with the spirit of that committee. Created as a check on the governments intelligence apparatus in the wake of some different surveillance scandals, the Intelligence Committees primary function is to

2

conduct vigorous oversight of Americas intelligence agencies. Vigorous oversight means more than just ensuring that the government doesnt break any laws or that national security is always protected though those are extremely important responsibilities. Vigorous oversight also means preserving Constitutional protections afforded to the American people, and protecting the public from intrusive government overreach. Among other things, the Intelligence Committee is charged with making sure that surveillance activities dont undermine Americans rights and liberties, abroad or at home. In recent months the public has seen firsthand what intrusive overreach looks like. As a result of the tidal wave of disclosures that began last June, the American people have finally been made aware of the full ramifications of the dragnet domestic surveillance that I and a few of my colleagues have been fighting to rein in for years. For the past several years I and a handful of other senators, to include Senator Udall of Colorado and our own Jeff Merkley, have been arguing that Americans had a right to know how surveillance laws were being secretly interpreted. We believed that once the public was informed about the true extent of the governments surveillance authorities, people would demand significant, meaningful reforms. So our small group has been asking tough questions of our own. We take advantage of the rare opportunities that we have to publicly question intelligence officials to widen the publics understanding of domestic

3

surveillance authorities, while working within the confines of classification rules. And weve continued to push hard for meaningful reforms. Chief among these, of course, is ending the ongoing bulk collection of Americans phone records. As has now been declassified, the bulk collection of Americans phone records began not long after the attacks of 9/11. I was a new member of the Senate Intelligence Committee back then, and like most Americans I will never forget that day. As our government scrambled to react in the days and weeks that followed, Congress passed broad new surveillance legislation known as the Patriot Act. Like a number of my colleagues I voted for the Patriot Act because it had an expiration date on it, which would force Congress to come back and debate these authorities more carefully once the immediate national emergency had passed. To my dismay, the law was reauthorized without major changes a few years later, and I was one of ten senators to oppose it at that time. The Patriot Act is a fairly broad surveillance law on its face. But what most Americans didnt know was that the secret interpretations of the law were even broader and Americans now know that the Patriot Act was used to justify the bulk collection of the phone and email records of huge numbers of law-abiding Americans. This collection originally began as part of President Bushs warrantless wiretapping program, but it then came to be justified under these secret interpretations of the Patriot Act.

4

To understand how that could take place you have to know a little about the most bizarre court in the U.S. - FISA. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court is like no other court youve ever seen. It was originally created in the 1970s to give intelligence agencies a legal venue where they could present classified evidence to federal judges and obtain routine probable cause warrants for intelligence purposes. Its authorities were modified periodically over the years, but in general it continued to resemble a regular federal district court, with the main difference being that its warrants and court orders targeted terrorists and spies instead of bank robbers and drug dealers. So far so good. But then, after 9/11, Congress passed new surveillance laws like the Patriot Act that didnt closely resemble laws that are used in the ordinary criminal context. The FISA Court was suddenly called upon to issue significant, binding interpretations of US surveillance laws and the Constitution entirely in secrecy, which is something that it was not well-designed to do. This is because when the government comes to the FISA Court and asks for permission to conduct specific surveillance activities including the dragnet collection of Americans phone and email records the Court almost always hears from the government and no one else. There is no one there to present the other side of the argument. This is not unusual if a court is considering a routine warrant application, but it is extremely unusual for a court that is conducting major legal

5

and constitutional analysis. It is a dramatic departure from the adversarial system that the American judiciary has been based on for over two centuries. And the consequence of this was that when the government came to the FISA Court and claimed that the Patriot Act authorized the bulk collection of Americans records, there was no one there to argue the other side. And when the Court issued its incredibly troubling interpretation of the law, it did so entirely in secret. Even before these legal interpretations became public, I spent years trying to warn people that the government was relying on secret law. When people read the Patriot Act on their laptops in the library down at the U of O or at a coffee shop in Medford, they wont see any references to the bulk collection of anything. But the Court accepted an interpretation of the law that stretched its plain meaning beyond recognition, and it did so entirely in secret. Defenders of this surveillance often argue that it isnt very intrusive they describe it as inoffensive data collection. I firmly disagree with that argument. Bulk collection of Americans records essentially creates a human relations database. Your phone records can reveal who you called, when you called them, how long you talked, and potentially even where you called from. Thats a lot of information. If I know that someone called a psychiatrist three times in a weekend, and twice after midnight, I know a lot about their private life. As the Vice President himself put it several years ago, I dont have to listen to your phone

6

calls to know what youre doing. If I know every single phone call you made, Im able to determine every single person you talked to. I can get a pattern about your life that is very, very intrusive. You can see how this is problematic. This is what motivated me to spend years working on this issue, writing classified letters, raising the issue at closed congressional hearings and in one-on-one meetings with senior officials. I also issued a number of public warnings about the fact that the government was relying on secret law, though obviously it was difficult to get people to pay attention when I couldnt explain the details of what was happening. People sometimes ask me, Ron, if you knew what was going on, why didnt you just tell everyone? This is something I wrestled with over the years. The Constitution says that the executive branch cant punish members of Congress for engaging in speech and debate, no matter what they say, but the Senate itself has chosen to adopt rules that require members to respect the secrecy of classified information. As I say, I considered how to proceed and frequently thought about what Senator Morse would have done. Im honestly not sure, and unfortunately Senator Morse is no longer around to give me his counsel. In the end I made the judgment that I could do more for the cause of reform by working within the rules and being inside the room for closed-door intelligence debates and in the position to ask hard questions in both closed and open hearings. I can see why some would

7

disagree with that judgment, but I was guided by the belief that in a free society like ours, the truth will always come out as long as people continue to ask the hard questions. And I hope Senator Morse would have found that to be a reasonable judgment. I like to think that Senator Morse would have seen it that way also. When I think about the importance of standing up for principle on matters of national security, I often think about his vote against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution fifty years ago. He was one of two senators to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, and when he did he said that the resolution was a blank check that would be cashed with the blood and treasure of the American people. He said that history would prove him right, and he remained a staunch critic of the war throughout his time in the Senate and afterward. Senator Morse was not one to shrink away from asking the tough questions, and he had faith in the publics ability to make the right decisions if given all of the facts. Like many of us today, he was a firm believer that the American people should be given the facts to make up their own minds about the United States foreign and national security policy. To him, circumventing the American peoples right to decide for themselves was not just a Constitutional failure, but a moral one.

He spent years after that vote not only asking whether America could win a war in Vietnam, but whether America had the right to wage it in the first place. In an interview with Face the Nation from shortly after the vote he said: I dont know why we think, just because we are mighty, that we have the right to substitute might for right. We now know the full repercussion of this resolution it led to a dramatic escalation in Americas involvement in Vietnam, and led to the loss of thousands of American lives. To make matters worse, documents declassified a few years ago show that the second of the two attacks on US Navy vessels that were used to justify the resolution actually did not happen at all. Those of you who are too young to remember the Gulf of Tonkin are probably reminded of another debate about war that took place forty years later, and that also involved a lot of fear and a lot of false information. When President Bush asked Congress for authorization to go to war in Iraq in 2002, the backdrop was a swirling public debate about whether Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction that he was likely to use against the United States. And we all know now that this debate involved a substantial amount of inaccurate information. On the night before the vote, I went to the Senate floor and spoke about my opposition to the war resolution. I mentioned a declassified letter

9

10

from the intelligence community that indicated that Saddam Hussein did not pose an imminent threat to the United States. Once again, I note that if the American people had the information they needed to make an informed decision, our history might have been quite different. As the debate unfolded in the Senate and I weighed the consequences of war against the consequences of inaction, I couldnt help but think about the similar situation that Senator Morse had found himself in nearly forty years earlier. It was one of the weightiest votes of my career, and in the end I decided that the likely costs were too great and the justifications too dubious, and I was one of twentythree senators to vote against the war. In hindsight I believe that was the right vote. I am very glad that Saddam Hussein is no longer on this Earth, and that his days of harming people are over. But the cost was thousands of lives lost and billions of taxpayer dollars spent, and in the end the Middle East was no closer to stability than it had been before the war started. I think that Senator Morse would have agreed that these costs were incredibly great, and I hope that he would have been proud of my vote. Now might be as good a time as any to talk a little about my personal relationship with Senator Morse. I first got to know him when I was a young law school student down at U of O. It was the end of my first year and Senator Morse

10

11

was running to reclaim the seat hed lost to Senator Packwood six years earlier. Here I was, still a young student, volunteering for a man who was and is an Oregon political hero for having the courage to stand up to his party and his president and all those who banged the drum for war. It was a position that had ultimately ended his Senate career, but he cared more about being right than being popular. He was an independent icon who fought for the rights of the politically powerless and the disenfranchised and he was willing to make hard decisions in order to improve the lives of all Americans. And I was lucky enough to be his driver. Needless to say he had an impact on my political education. So much so that I often attribute the direction my career has headed in part to my time working on those campaigns. As Senator Morses driver I got to spend a lot of time with him as he met with constituents throughout the state. He would shake hands outside of lumber mills and union halls. He would listen to the needs and concerns of Oregonians. Senator Morse was also the one who introduced me to the concerns of seniors, issues that I would work on exclusively for years after leaving college and would eventually drive my interest in running for public office. In 1972, Medicare was still a pretty new thing. It had only been signed into law seven years earlier and like some other major health care initiatives we may

11

12

know, it took some time to get it coordinated and work out the bugs. So, when Senator Morse would meet with elderly constituents they would ask for help working through this Medicare issue or that Medicare issue. Morse would often turn to me and say Ill have Ron look into it for you. There I was, in my mid20s, with a political legend telling me that I was going to tackle a new policy field and Ill tell you it was simultaneously scary and exciting. That experience led me to examine the myriad issues that seniors faced, especially in the arena of health care. Not long after finishing law school I became a part-time instructor in gerontology at several Oregon colleges and a co-founder of the Oregon Gray Panthers. Of course, I know that Senator Morse would have hit the roof over the news from this past week. Those of you who have been following this story will know that the battle over domestic surveillance has taken a very troubling turn, in a way that goes directly to the question of whether Congress can conduct effective oversight of Americas national security apparatus. Because of the classified nature of some of the information, I am somewhat limited in what I can say about this, but Ill lay out what I can. The Chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Senator Feinstein, gave a bombshell speech last week, and said, in a nutshell, that the CIA secretly searched a computer system that was located at the CIA but that was used by Senate staff investigating the CIAs past interrogation practices, and

12

13

that CIA personnel searched through congressional files in order to find out if the committee staff possessed certain documents that contradicted the CIAs previous statements about interrogation and torture. Senator Feinstein said on the Senate floor that this appears to be a serious violation of the separation of powers laid out in our Constitution, as well as a violation of the rules that prohibit the CIA from conducting searches and surveillance inside the United States. In short, its an incredibly serious matter. And Im increasingly troubled that the CIAs actions indicate that there are a number of senior CIA officials who simply dont want the public to learn what this Senate investigation into interrogation is all about. Fortunately, the findings of this interrogation investigation have been laid out in an historic report that I was proud to support along with a bipartisan group of my colleagues. And Ill be working with my colleagues to make sure that this report is declassified and made available to the public, because I think its more important to give the American people the full story about how torture happened, so that we can have better policies in the days ahead about how to ensure that the mistakes of the past are never repeated. I also plan to keep pressing senior CIA officials to explain their actions in this matter. For example, at the Intelligence Committees last open hearing, before this story became public, I asked the CIA Director about a federal law known as

13

14

the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. I and my intelligence staffer who is a Beaverton High School graduate named John Dickas often spend weeks preparing for open hearings and trying to ask the most useful questions we can in a way that is consistent with the Senates confidentiality and classification rules. So, based on our concerns about this matter, we decided that it would be useful to ask the CIA Director whether the federal Computer Fraud and Abuse Act applied to the CIA. The CIA Director now acknowledges that this law does apply to the CIA, and I think thats an admission that could be important going forward, as Congress seeks to determine whether the CIAs actions have violated particular laws or the Constitution. Those of you who have been following this story particularly closely might have noticed that last Tuesday the Director of the CIA tried to suggest that this unprecedented search of congressional files never took place at all, even though CIA officials have spent the past few weeks trying to justify it. In fact, the CIAs own spokesman has said that the CIA conducted this search to find out if the Intelligence Committee had obtained the particular files in question. But in a public interview last Tuesday, the CIA Director said, and I quote, As far as the allegations of CIA hacking into Senate computers, nothing could be further from the truthwe wouldnt do thatthats just beyond the scope of reason in terms of

14

15

what we would do. I think any eighth-grader could tell you that these statements do not add up. This is just the latest example of what Ive called a culture of misinformation. What has happened is that the reliance on a secret body of law and secret surveillance authorities have created a culture in which senior officials frequently make inaccurate and misleading statements about their authorities and activities, and then fail to correct the public even when they are called out on it. If these misstatements were due to simple sloppiness or imprecision, they would sometimes sound better and sometimes worse than the actual truth. But thats not whats been happening. These misstatements have consistently exaggerated the effectiveness of domestic surveillance programs and consistently understated their intrusiveness, and the slew of recently declassified documents makes it clear that this has been happening both in public and in private.

To be clear, Im not talking about the rank and file employees of the intelligence agencies. On the contrary, after thirteen years on the Senate Intelligence Committee I can say with confidence that the men and women who make up Americas intelligence agencies are extraordinarily dedicated professionals who make enormous sacrifices to help keep our country safe. The pattern of deceptive statements that Im talking about has come from the ranks of

15

16

the senior officials, and while thats obviously troubling the silver lining is that means this culture of misinformation can be reformed. Ill give you a few examples of the inaccurate and misleading statements that Im talking about. In 2012, the Director of the NSA was asked about domestic surveillance in a public forum, and he said that the NSA doesnt hold data on US citizens. He could have avoided the question and given a non-answer. But he unequivocally said no. You can see that statement on YouTube. In another public forum a few months later he said that former NSA employees allegations about bulk collection werent true, even though bulk collection had been going on for years. No matter how you parse his words on that one, thats another incredibly misleading statement.

If the NSA Director had simply declined to answer those questions and continued to operate this giant phone records collection program in secret I wouldnt have liked it, but I wouldnt have said he was misleading people. But thats not what happened. Similarly, Justice Department officials have testified on multiple occasions that the business records provision of the Patriot Act is analogous to a grand jury subpoena. Im sure weve got some lawyers or budding lawyers in the house tonight, so if any of you are aware of a grand jury subpoena that allows for the

16

17

collection of millions of peoples records on an ongoing daily basis, please come up afterwards and tell me about it. I make that request almost every time I give a speech on this topic, and I havent had any takers yet. And, of course, as many of you know in response to the frequent misleading statements from the NSA Director, I asked the Director of National Intelligence our nations top intelligence official at a public hearing last spring whether the government holds any data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans and he said no. I was surprised by that answer since Id sent him the question a day in advance. So I had my intelligence staffer call the Directors staff soon afterward and urge them to amend the Directors answer. The Directors office acknowledged that the Directors answer was inaccurate, but they declined to correct the public record. To me, thats an example of how embedded this culture of misinformation has become. It is not possible to know whats in a witness head when they are sitting at the table in front of the bright lights, but the decision to let that inaccurate statement stand on the public record was clearly a deliberate decision. My staff and I were still trying to figure out what to do next when the tidal wave of disclosures that began last June finally showed the public what was really going on.

17

18

Which is probably leading most of you to think, Okay Ron how do you want to fix it? We are at a unique time in our constitutional history. In the coming months Americans will have an opportunity to reshape the way surveillance is conducted in our nation. Were already beginning to see signs of a new day. Just last week the ranking Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, whose district includes the NSA headquarters, announced for the first time that he supports ending the NSAs bulk phone records collection. I plan to work very hard to see that this major reform is made as fast as possible. As Ive said before, I want American intelligence agencies to be able to quickly obtain the information that they actually need to protect our country. But this can be done without collecting the personal information of huge numbers of lawabiding Americans. Bulk collection is ineffective, overly intrusive and constitutionally unsound. It is time to end that program. And I will continue to work with my colleagues to amend the law to prohibit future administrations from seeking to restart bulk collection in the future. I also plan to continue pursuing greater protections for Americans internet communications as well. One of the most important reforms that I believe needs to be made in this area involves closing what I call the back-door searches loophole. This loophole is found in section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

18

19

which was intended to give the government more authority to collect the communications of foreigners outside the United States. However, the disclosures of the past several months have shown that thousands of Americans have had their communications swept up under this authority, and this includes a significant number of wholly domestic communications. The back door search loophole allows the NSA to go through this pile of supposedly foreign communications and search for the communications of specific Americans without needing to get a warrant. I will tell you that is an end run around the Fourth Amendment. If your communications happen to be collected under section 702 authorities, the government doesnt need a warrant to search for them, even though the Constitution says it does. This is a back door that this Congress needs to be shut and shut tight. Ive talked about the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court already and I believe one of the most important reforms we can make is to bring that court more in line with more than 200 years of judicial precedent. When this court considers major cases it should hear both sides of the argument, and its binding interpretations of the law and the Constitution should be made available to the American public. This means that Congress needs to create a public advocate to argue the other side of major cases before the Court, and to press for the disclosure of major rulings of law. These two aspects are exceedingly important. Civil

19

20

liberties cannot get short shrift during court hearings while the resulting ruling remains classified. The rights of the American people are doubly imperiled in a system like that and any real surveillance reform effort should include these protections. In my view, thats how we end the culture of misinformation that has facilitated a decade of dragnet surveillance the governments reliance on secret law must end. This is an issue that is not ideological - its constitutional. It is not partisan - its American. And knowing Wayne Morse the way I did and the way you all do, I dont think there is any questions about where he would have come down on this issue. And I have seen firsthand how standing alone on important issues of freedom and security can be the first step toward winning an important debate. Heres an example. When the annual Intelligence Authorization bill was going through the Senate Intelligence Committee in late 2012, it included a few provisions that were meant to stop intelligence leaks but that would have been disastrous to the news medias ability to report on foreign policy and national security. Among other things, it would have restricted the ability of former government officials to talk to the press, even about unclassified foreign policy matters. And it would have prohibited intelligence agencies from making anyone outside of a few high-level officials available for background briefings, even on

20

21

unclassified matters. These provisions were intended to stop leaks, but its clear to me that they would have significantly encroached upon the First Amendment, and led to a less-informed public debate on foreign policy and national security matters. These so-called anti-leaks provisions went through the committee process in secret, and the bill was agreed to by a vote of 14 to 1 (And Ill let you all guess who that nay vote was). The bill then made its way to the Senate floor and a public debate. Once the bill became public, of course, it was promptly eviscerated by media and free speech advocates, who saw it as a terrible idea. I put a hold on the bill so that it could not be quickly passed without the discussion it deserved and within weeks, the offending anti-leaks provisions were removed. When I think back at my formative years, when I had a full head of hair and rugged good looks, the influence of two men stand out. One is inarguably my father. He taught me the importance of asking questions, of seeking accountability, and that the public has a right to know what their government is doing in their name and a responsibility to be engaged citizens. His journalistic ethic has infused everything I do. The second is Wayne Morse. Not a day goes by when I am not reminded how his influence has helped to shape my life and the lives of so many Oregonians. Senator Morse showed that you could be both independent and pragmatic. I think that should be the mission of every Oregon public official.

21

22

And Wayne Morse took that thinking a step further. When his principles dictated that he could no longer be a member of the Republican party, he left and became an independent. When those principles began to align more with the Democratic party he joined them. When his party let him down he became an outspoken critic of the war and a Democratic president. These were not simple decisions, but ones that were based in principle. I dont recommend that any Oregon officials compare themselves to Senator Wayne Morse personally, I dont like my odds. But I believe his legacy has something to teach all Oregonians about the value of public service, and something to teach those of us who are lucky to represent Oregon in Congress about the value of asking tough questions and being skeptical of the excessive secrecy that often surrounds national security policy. I think that all of us in public service should hope to find opportunities to take out the Wayne Morse mantle. I know I hope to do that, and on occasion there are even going to be some issues where you may see me bring in my own folding chair.

Thank you.

22

You might also like

- Senators Urge Trump To Keep Promises On Medicare and MedicaidDocument8 pagesSenators Urge Trump To Keep Promises On Medicare and MedicaidTom UdallNo ratings yet

- Combined College Affordability ClipsDocument40 pagesCombined College Affordability ClipsSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Wyden Amdts To Cybersecurity and Information Sharing Act (CISA)Document6 pagesWyden Amdts To Cybersecurity and Information Sharing Act (CISA)Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Remarks of Senator Ron Wyden at TechFestNWDocument5 pagesRemarks of Senator Ron Wyden at TechFestNWSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map06 MoistDry 073114Document1 pageMap06 MoistDry 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Wyden: Floor Statement - Interrogation ReportDocument11 pagesWyden: Floor Statement - Interrogation ReportSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

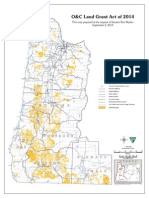

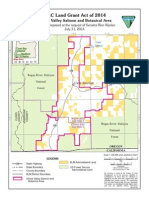

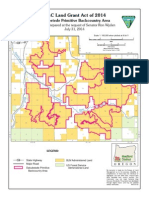

- O&C Land Grant Act of 2014Document1 pageO&C Land Grant Act of 2014Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- O&C Act of 2014 Section by SectionDocument8 pagesO&C Act of 2014 Section by SectionSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- O&C Act of 2014 Covered LandsDocument1 pageO&C Act of 2014 Covered LandsSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Bill Text O&C Act 2014Document157 pagesBill Text O&C Act 2014Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- O&C Act of 2014 Section by SectionDocument8 pagesO&C Act of 2014 Section by SectionSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08A CSNM Expansion 073114Document1 pageMap08A CSNM Expansion 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map07C ClackamasWater 073114Document1 pageMap07C ClackamasWater 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- The O&C Act of 2014 Bill TextDocument163 pagesThe O&C Act of 2014 Bill TextSenator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08D MolallaNationalRecArea 073114Document1 pageMap08D MolallaNationalRecArea 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map07B HillsboroWater 073114Document1 pageMap07B HillsboroWater 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map03 ConservationNetwork 073114Document1 pageMap03 ConservationNetwork 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map06 MoistDry 073114Document1 pageMap06 MoistDry 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08B IllinoisValley 073114Document1 pageMap08B IllinoisValley 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map01 CoveredLands 073114Document1 pageMap01 CoveredLands 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map02 ForestryEmphasis 073114Document1 pageMap02 ForestryEmphasis 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map04 ConservationEmphasis 073114Document1 pageMap04 ConservationEmphasis 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map05 LegacyOldGrowth 073114Document1 pageMap05 LegacyOldGrowth 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map07A McKenzieWater 073114Document1 pageMap07A McKenzieWater 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08L SpecialEnvironmentalZones 073114Document1 pageMap08L SpecialEnvironmentalZones 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map07D SpringfieldWater 073114Document1 pageMap07D SpringfieldWater 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08J CrabtreeValley 073114Document1 pageMap08J CrabtreeValley 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08G WellingtonWildlands 073114Document1 pageMap08G WellingtonWildlands 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- Map08F Dakubatede 073114Document1 pageMap08F Dakubatede 073114Senator Ron WydenNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Stark County Area Transportation Study 2022 Crash ReportDocument148 pagesStark County Area Transportation Study 2022 Crash ReportRick ArmonNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Directions: U. S. CitiesDocument2 pagesIntermediate Directions: U. S. CitiesNouvel Malin BashaNo ratings yet

- Organic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDDocument3 pagesOrganic Theory: HL Bolton (Engineering) Co LTD V TJ Graham & Sons LTDKhoo Chin KangNo ratings yet

- Residential Lease Agreement: Leased PropertyDocument11 pagesResidential Lease Agreement: Leased PropertyjamalNo ratings yet

- Genealogy of Jesus ChristDocument1 pageGenealogy of Jesus ChristJoshua89No ratings yet

- LAW1011 - Business and Family Law - Course Outline Spring 2022Document7 pagesLAW1011 - Business and Family Law - Course Outline Spring 2022Maria PatinoNo ratings yet

- Beams10e - Ch09 Indirect and Mutual HoldingsDocument36 pagesBeams10e - Ch09 Indirect and Mutual HoldingsLeini Tan100% (1)

- Entry of AppearanceDocument3 pagesEntry of AppearanceConrad Briones100% (1)

- DepED Sports Meet Entry FormDocument1 pageDepED Sports Meet Entry FormMarz TabaculdeNo ratings yet

- E 580Document10 pagesE 580cokecokeNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship Reviewer FinalsDocument7 pagesEntrepreneurship Reviewer FinalsEricka Joy HermanoNo ratings yet

- Working Capital Management Cash ManagementDocument9 pagesWorking Capital Management Cash ManagementRezhel Vyrneth TurgoNo ratings yet

- Career Development Work Values q3m1.Document4 pagesCareer Development Work Values q3m1.almafebe caselNo ratings yet

- ESTATE TAX SUMMARYDocument35 pagesESTATE TAX SUMMARYRhea Mae Sa-onoyNo ratings yet

- CG and Other StakeholdersDocument13 pagesCG and Other StakeholdersFrandy KarundengNo ratings yet

- Democracy (Anup Shah) - Global IssuesDocument47 pagesDemocracy (Anup Shah) - Global IssuesjienlouNo ratings yet

- RMC 72-2004 PDFDocument9 pagesRMC 72-2004 PDFBobby LockNo ratings yet

- Cisco RV340, RV345, RV345P, and RV340W Dual WAN Security RouterDocument13 pagesCisco RV340, RV345, RV345P, and RV340W Dual WAN Security RouterluzivanmoraisNo ratings yet

- Blue Star Limited: Accounting Policies Followed by The CompanyDocument8 pagesBlue Star Limited: Accounting Policies Followed by The CompanyRitika SorengNo ratings yet

- Brown v. YambaoDocument2 pagesBrown v. YambaoBenjie CajandigNo ratings yet

- List 2014 Year 1Document3 pagesList 2014 Year 1VedNo ratings yet

- Foreign Affairs March April 2021 Issue NowDocument236 pagesForeign Affairs March April 2021 Issue NowShoaib Ahmed0% (1)

- Official Coast Guard Biograpahy On Terri A. DickersonDocument2 pagesOfficial Coast Guard Biograpahy On Terri A. DickersoncgreportNo ratings yet

- Synopsis/ Key Facts:: TAAR V. LAWAN (G.R. No. 190922. October 11, 2017)Document16 pagesSynopsis/ Key Facts:: TAAR V. LAWAN (G.R. No. 190922. October 11, 2017)Ahmed GakuseiNo ratings yet

- International Criminal Law PDFDocument14 pagesInternational Criminal Law PDFBeing IndianNo ratings yet

- байден презентDocument7 pagesбайден презентAlinа PazynaNo ratings yet

- Commodity Money: Lesson 1Document8 pagesCommodity Money: Lesson 1MARITONI MEDALLANo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis HyundaiDocument12 pagesRatio Analysis HyundaiAnkit MistryNo ratings yet

- Agenda 21Document2 pagesAgenda 21Hal Shurtleff100% (1)

- Provincial Investigation and Detective Management Unit: Pltcol Emmanuel L BolinaDocument17 pagesProvincial Investigation and Detective Management Unit: Pltcol Emmanuel L BolinaCh R LnNo ratings yet