Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

Uploaded by

Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views5 pagesIn this unpublished decision, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) dismissed a DHS appeal and upheld the termination of proceedings upon finding that assault on a female under N.C. Stat. 14-33(c)(2) is neither a crime involving moral turpitude nor a crime of domestic violence under the categorical approach, and that the statue was not divisible under Descamps v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2276 (2013). The Board also stated the cyberstalking under N.C. Stat. 14-196.3 is not a crime involving moral turpitude. The decision was written by Member Roger Pauley.

Looking for IRAC’s Index of Unpublished BIA Decisions? Visit www.irac.net/unpublished/index

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn this unpublished decision, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) dismissed a DHS appeal and upheld the termination of proceedings upon finding that assault on a female under N.C. Stat. 14-33(c)(2) is neither a crime involving moral turpitude nor a crime of domestic violence under the categorical approach, and that the statue was not divisible under Descamps v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2276 (2013). The Board also stated the cyberstalking under N.C. Stat. 14-196.3 is not a crime involving moral turpitude. The decision was written by Member Roger Pauley.

Looking for IRAC’s Index of Unpublished BIA Decisions? Visit www.irac.net/unpublished/index

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

2K views5 pagesEduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

Uploaded by

Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCIn this unpublished decision, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) dismissed a DHS appeal and upheld the termination of proceedings upon finding that assault on a female under N.C. Stat. 14-33(c)(2) is neither a crime involving moral turpitude nor a crime of domestic violence under the categorical approach, and that the statue was not divisible under Descamps v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2276 (2013). The Board also stated the cyberstalking under N.C. Stat. 14-196.3 is not a crime involving moral turpitude. The decision was written by Member Roger Pauley.

Looking for IRAC’s Index of Unpublished BIA Decisions? Visit www.irac.net/unpublished/index

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

'

-'

'

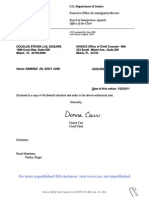

Jama Ibrahim

6065 Roswell Rd. N.E., Suite 950

Atlanta, GA 30328

Name:GOMEZJURADO,EDUARDO

U.S. Department of Justice

COPY

Executive Ofce for Imigration ev

Board of Immigation Appeals

Office of the Clerk

5 I 07 Leesburg Pike, Suite 2000

Fals Church, Virginia 20530

DHS/ICE Office of Chief Counsel - A TL

180 Spring Street, Suite 332

Atlanta, GA 30303

A 090-764-102

Date of this notice: 3/28/2014

Enclosed is a copy of the Board's decision and order in the above-referenced case.

Enclosure

Panel Members:

Pauley, Roger

Sincerely,

Doc t

Donna Carr

Chief Clerk

sch 'iva rz.A.

Userteam: Docket

For more unpublished BIA decisions, visit www.irac.net/unpublished

I

m

m

i

g

r

a

n

t

&

R

e

f

u

g

e

e

A

p

p

e

l

l

a

t

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

|

w

w

w

.

i

r

a

c

.

n

e

t

Cite as: Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

)

:

U.S. Deparent of Justice

Executive Ofce fr Imigation Review

Decision of the Board of Imigation Appeals

Falls Church, Virginia 20530

File: A090 764 102 - Atlanta, GA Date:

MAR 2 8 2014

In re: EDUARDO GOMEZJURADO a.k.a. Eduardo Gomez Jurado

IN REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS

APPEAL

ON BEHALF OF RESPONDENT: Jama A. Ibrahim, Esquire

ON BEHALF OF DHS:

CHARGE:

Gene Hamilton

Assistant Chief Counsel

Notfoe: Sec. 237(a)(2)(A)(ii), I&N Act [8 U.S.C . . 1227(a)(2)(A)(ii)] -

Convicted of two or more crimes involving moral turpitude

Sec. 237(a)(2)(E)(i), I&N Act [8 U.S.C. 1227(a)(2)(E)(i)] -

Convicted of crime of domestic violence, stalking, or child abuse, child

neglect, or child abandonment

APPLICATION: Termination

The Department of Homelad Security ("DHS") appeals fom an Immigration Judge's

March 4, 2013, decision terminating proceedings. The respondent has filed a brief in opposition

to the appeal. For the reasons that fllow, the appeal will be dismissed.

At issue on appeal is whether the DHS met its burden of proving that the respondent's

August 2010 convicton for assault on a female in violation of North Caolina law is a crime

involving moral turpitude, W wcce wit a 19 conviction for felony tef undr

' law to satisf the charge of removal arising under section 237(a)(2)(A)(ii) or the

Immigration and Nationality AQ. In addition, the DJIS argues on appeal that the assault on a

female conviction under section 14-33(c)(2) of te No Carolina statute is also a crime of

domestic violence, satisfing the removal charge under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the Act.1 We

1 I its Notice of Appeal, the DHS also raised the question whether the Immigration Judge erred

in fnding that it had failed to prove that the respondent's March 2012 conviction fr

cyberstalking in violation of section 14-196.3 constituted a crime involving moral turpitude.

However, in its appeal brief, the DHS does not elaborate on this argument, nor support it with

pertinent legal authority. We therefore deem this argument abandoned. Nevertheless, to the

extent that the DHS challenges the Immigration Judge's findings with regard to whether the

cyberstalking conviction can go towards satisfing the charge of removal under section

237(a)(2)(A)(ii) of the Act, we afirm the Immigration Judge's finding in this regard (Tr. at

85-86). See Cano v. US At'y Gen., 709 F.3d 1052, 1053 n. 3 (I Ith Cir. 2013) (analysis must

(Continued . . . . )

I

m

m

i

g

r

a

n

t

&

R

e

f

u

g

e

e

A

p

p

e

l

l

a

t

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

|

w

w

w

.

i

r

a

c

.

n

e

t

Cite as: Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

A090 764 102

review these legal questions de novo. See 8 C.F.R. 1003.l(d)(3)(ii). We also note that there

are no contested questions of fct arising in this appeal that would tigger clear error review. See

8 C.F.R.

1003. l(d)(3)(

i).

The question wheter te assault conviction under the above-refrenced section of North

Carolina law constitutes a crime involving moral turpitude is infored by the Supreme Court's

decision in Descamps v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2276 (2013), which was issued afer the

Immigation Judge rendered his decision in this case. In Descamps, the Supreme Court

explained tat the modifed categorical approach operates narrowly, and applies only if: (1) the

statute of conviction is divisible in the sense that it lists multie discrete ofenses as enumerated

alteratives or defines a single ofense by reference to disjunctive sets of "elements,"2 more than

one combination of which could support a conviction, and (2) some (but not all) of those listed

ofenses or combinations of disjunctive elements are a categorical match to the relevant generic

standad. Id. at 2281, 2283. Thus, afer Descamps te modifed categorical approach does not

apply merely because the elements of a crime can sometimes be proved by reference to conduct

tat fits a generic fderal standard; according to the Descamps Court, such crimes are "overbroad"

but not "divisible." Id. at 2285-86, 2290-92.3

.

The state statute under which the respondent was convicted for misdemeanor assault provides

in relevant part that" . . . any person who commits any assault, assault and battery, or affay, is

guilty of a Class Al misdemeanor if, in the course of the assault, assault and battery, or afay, he

or she . . . (2) [a]ssaults a female, he being a male person at least 18 years of age." See N.C. Gen.

Stat. 14-33(c)(2). The Immigration Judge fund that this statute did not categorically defne a

crime involving moral turpitude, but pursuant to the parties' agreement, conducted a modified

categorical analysis of the conviction record, to determine if the conviction would support the

charge under section 237(a)(2)(A)(ii) of the Act (I.J. at 2-3).

We disagree that under Descamps v. United States, supra, the statute lends itself to a

modified categorical inquiry into whether the respondent's conviction thereunder is for a crime

involving moral turpitude. While the language referencing the commission of "any assault,

determine if least culpable conduct necessary to. sustain a conviction under the statute meets the

sta.1 1dard of a crime involving moral tupitude). The cyberstag conviction was not alleged as

a fctual predicate fr the charge under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the Act, and the DHS does not

allege on appeal that this conviction would support removal under section 237(a)(2)(E)(i) of the

Act. See DHS's Brief at 3, n. 2 and Exh. 5.

2 By "elements," we understand the Descamps Court to mean those facts about a crime which

must be proved to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt and about which the jury must agree by

whatever margin is required to convict in the relevant jurisdiction. Id. at 2288 (citing Richardson

v. United States, 526 U.S. 813, 817 (1999)).

3 The Eleventh Circuit has held that the requirements of the categorical and modified categorical

approaches may not be relaxed in CIMT cases . .Fajardo v. US. Att' Gen., 659 F.3d i303, 1305

(11th Cir. 2011).

.

2

I

m

m

i

g

r

a

n

t

&

R

e

f

u

g

e

e

A

p

p

e

l

l

a

t

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

|

w

w

w

.

i

r

a

c

.

n

e

t

Cite as: Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

. . ,

"o '

A090 764 102

assault and battery, or affay," describes alterative means of committing the crime, we do not

read te Supreme Court's opinion to support a conclusion tat these are disparate "elements" of

the crime, supporting a modified categorical approach. Moreover, the balance of the statute

relating to te perpetator being "a male person at least 18 years of age" who "assaults a fmale"

suggests no alterative elements of assault--certainly no question about a domestic

relationship-about which North Carolina jurors must agree in order to convict. See Descamps

v. United States, supra, at 2285 n. 2. We therefore fnd the modifed categorical approach

undertaken here to be unwarranted under intervening precedent.4

-

Even if the modified categorical approach was appropriate here, we afrm the Immigration

Judge's determination that under noticeable documen!s, the.DRS did not meet its burden to prove

that the respondent's assault on a female conviction involved moral turpitude. Fajardo v. US

Att ' Gen., supra. As the Immigation Judge fund, the documents indicate that the respondent

was convicted afer tial the district.court acting as-the tier of fct (I.J. at 2-3). The record of

conviction; which included.the warrant of arrest and the judgent (Exh. 3), does not reflect the

fctual basis fr the fnding of guilty, insofar as the warrat, even assuming that it is equivalent

to an indictent, was not shown on this record to be the basis fr a plea or fding of guilty (IJ.

at 3; Tr. at 52-57). Accordingly, assuming that a modified categorical approach was appropriate,

we fnd that the Immigration Judge properly found that the DHS did not prove that this record

reflected the type of "willfl" "infliction of bodily harm upon a person with whom one has . . . a

familial relationship" that would indicate that the respondent's assault conviction involves moral

tuitude. Matter ofTran, 21 I&N Dec. 291, 294 (BIA 1996).

Furthermore, we afirm the Immigration Judge's fnding that the record does not support a

fnding that the conviction fr assault on a female was fr a crime of domestic violence. First,

the North Carolina statute at issue does not set forth a categorical crime of violence as described

under 18 U.S.C. 16(a),5 which would be necessary to a finding of a "domestic violence" crime.

See Matter of Velasquez, 25 I&N Dec. 278, 279-80 (BIA 2010). That is because an "assault" for

purposes of this statute is defned according to common law to include a battery, which requires

a showing oJ. any level of force, either direct or indirect, to the person of another. See United

States v. Kelly, 917 F.Supp.2d 553, 559 (W.D.N.C. 2013) (citing State v. Britt, 154 S.E.2d 519

(N.C. 1967)). Battery under North Carolina law does not require the application of violent frce

or force capable of causing injury, and indeed has been described as requiring only "ofensive

touching." See Cit of Greenville v. Haood, 502 S:E.2d 430, 433 (N.C. Ct. App. 1998). We

4 We note that the parties conceded that the respondent's 1996 conviction for grand thef under

section 812.014 of the Florida statutes was categorically a crime involving moral turpitude(Tr. at

82). However, Descamps v. United States, supra, may undermine any such fnding, since we

read the Florida thef statute to permit conviction for temporary or permanent takings, raising the

question whether tese would constitute alterative elements to the ofense, so as to invite a

modifed categorical approach under relevat precedent.

5 Because the respondent's conviction under section 14-33(c)(2) of the North Carolina statute

was for a misdemeanor, it can only constitute a crime of violence if it is "an ofense that has as

an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical frce against the person or

property of another." See Matter of Velasquez, 25 I&N Dec. 278, 280 (BIA 2010).

3

I

m

m

i

g

r

a

n

t

&

R

e

f

u

g

e

e

A

p

p

e

l

l

a

t

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

|

w

w

w

.

i

r

a

c

.

n

e

t

Cite as: Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

.

' "

A090 764 102

have held that this conduct does not equate to an element of "physical force" that is required to

qualif an ofense as a crime of violence under 18 U.S.C. 16(a). See Matter of Velasquez,

supra, at 281-82; Johnson v. United States, 559 U.S.133 (2010). Even if we assume that the

underlying assault conviction would not include a battery, it does not appear that violent force is

always a requisite element of the crime of assault under North Carolina, since common law does

not consistently require the showing of "frce and violence" to convict under the statute. See

United States v. Kelly, supra, at 557-58 (noting cases wherein conviction for assault predicated

on showing of "frce or violence" or a show of force).

We do not fi nd that a modified categorical inquiry into the crime of violence question is

viable in light of Descamps v. United States, supra. Furthermore, even if it were, the record does

not contain the requisite judicially noticeable documents to reveal the maner in which the

"assault" conviction occurred, since the record does not reflect that the facts in the "warrat"

were_ Q. onsidered ad fund by the trier of fct. These findings mae unnecessary our

consideration of evidence outside of the record of conviction to determine that the victim ad the

respondent were in a requisite "domestic" relationship, as urged by the DHS on appeal. See

Bianco v. Holder, 624 F.3d 265 (5t Cir. 2010)

;

DHS's Brief at 12-13.

Accordingly, we fnd no cause to disturb the Immigration Judge's decision to terminate

proceedings. The fllowing order will therefore be entered.

ORDER: The appeal is dismissed.

4

I

m

m

i

g

r

a

n

t

&

R

e

f

u

g

e

e

A

p

p

e

l

l

a

t

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

|

w

w

w

.

i

r

a

c

.

n

e

t

Cite as: Eduardo Gomez Jurado, A090 764 102 (BIA Mar. 28, 2014)

You might also like

- S V MtshwaeliDocument2 pagesS V MtshwaeliMaka T ForomaNo ratings yet

- M-B-, AXXX XXX 672 (BIA Sept. 25, 2014)Document5 pagesM-B-, AXXX XXX 672 (BIA Sept. 25, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Sean Terry Darwin Haynes, A036 574 645 (BIA Dec. 2, 2016)Document18 pagesSean Terry Darwin Haynes, A036 574 645 (BIA Dec. 2, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Ayaz Khan, A071 801 450 (BIA Oct 12, 2017)Document6 pagesAyaz Khan, A071 801 450 (BIA Oct 12, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Josefa Carrillo-Pablo, A202 097 908 (BIA June 2, 2016)Document6 pagesJosefa Carrillo-Pablo, A202 097 908 (BIA June 2, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Appeal ID 5330457 (BIA Oct. 26, 2022)Document3 pagesAppeal ID 5330457 (BIA Oct. 26, 2022)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- N-M-, AXXX XXX 196 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document9 pagesN-M-, AXXX XXX 196 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Answers To Bar Questions 2017-2018: Remedial Law Crim ProcDocument3 pagesAnswers To Bar Questions 2017-2018: Remedial Law Crim ProcFrancisco Ashley Acedillo100% (2)

- Manafort Motion To SuppressDocument63 pagesManafort Motion To SuppresssonamshethNo ratings yet

- Motion For Extension of Time To File Counter AffidavitDocument2 pagesMotion For Extension of Time To File Counter AffidavitBibo Gunther86% (7)

- Chhrey Chea, A027 321 642 (BIA Dec. 22, 2014)Document9 pagesChhrey Chea, A027 321 642 (BIA Dec. 22, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Roberto Javier Blanco-Perez, A092 981 108 (BIA May 14, 2015)Document8 pagesRoberto Javier Blanco-Perez, A092 981 108 (BIA May 14, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- I-D-R-C-, AXXX XXX 214 (BIA Oct. 27, 2017)Document7 pagesI-D-R-C-, AXXX XXX 214 (BIA Oct. 27, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Eddy Jose Ramirez, A028 859 292 (BIA Jan. 20, 2011)Document8 pagesEddy Jose Ramirez, A028 859 292 (BIA Jan. 20, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Fernando Cardeas Cazares, A014 273 381 (BIA Jan. 27, 2017)Document5 pagesFernando Cardeas Cazares, A014 273 381 (BIA Jan. 27, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Salvador Hernandez-Garcia, A097 472 829 (BIA Sept. 20, 2013)Document15 pagesSalvador Hernandez-Garcia, A097 472 829 (BIA Sept. 20, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Edwin Alexander Jandres-Aguiluz, A073 674 189 (BIA Nov. 13, 2014)Document13 pagesEdwin Alexander Jandres-Aguiluz, A073 674 189 (BIA Nov. 13, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC0% (1)

- Santino Fabian Alarcon-Gomez, A201 227 554 (BIA Apr. 2, 2014)Document8 pagesSantino Fabian Alarcon-Gomez, A201 227 554 (BIA Apr. 2, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Ramiro Hernandez, A079 350 585 (BIA June 27, 2011)Document6 pagesRamiro Hernandez, A079 350 585 (BIA June 27, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Clayton Hugh Anthony Stewart, A043 399 408 (BIA Feb. 11, 2015)Document16 pagesClayton Hugh Anthony Stewart, A043 399 408 (BIA Feb. 11, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- H-M-F-, AXXX XXX 345 (BIA March 29, 2017)Document7 pagesH-M-F-, AXXX XXX 345 (BIA March 29, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Ronal Antonio Dominguez, A040 541 465 (BIA Oct. 3, 2017)Document15 pagesRonal Antonio Dominguez, A040 541 465 (BIA Oct. 3, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Rajesh Chitherbhai Makwana, A088 578 134 (BIA Jan. 5, 2015)Document18 pagesRajesh Chitherbhai Makwana, A088 578 134 (BIA Jan. 5, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Maria Jose Reyes, A076 916 481 (BIA July 8, 2014)Document4 pagesMaria Jose Reyes, A076 916 481 (BIA July 8, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Juan Pablo Zea-Flores, A041 737 150 (BIA April 6, 2011)Document5 pagesJuan Pablo Zea-Flores, A041 737 150 (BIA April 6, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- J. German Benitez-Lopez, A092 298 255 (BIA May 29, 2014)Document5 pagesJ. German Benitez-Lopez, A092 298 255 (BIA May 29, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Tamara Jackeline Aleman, A073 110 365 (BIA June 18, 2013)Document6 pagesTamara Jackeline Aleman, A073 110 365 (BIA June 18, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Stefan Abhishek Vincent, A208 357 277 (BIA April 14, 2017)Document12 pagesStefan Abhishek Vincent, A208 357 277 (BIA April 14, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Jose Emilio Alvarado A208 090 238 (BIA June 2, 2016)Document3 pagesJose Emilio Alvarado A208 090 238 (BIA June 2, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- C-P-O-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 2, 2015)Document3 pagesC-P-O-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 2, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Edgar Armando Valenzuela-Garcia, A079 651 539 (BIA March 10, 2011)Document12 pagesEdgar Armando Valenzuela-Garcia, A079 651 539 (BIA March 10, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- J-K-O-, AXXX XXX 418 (BIA May 10, 2017)Document13 pagesJ-K-O-, AXXX XXX 418 (BIA May 10, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC0% (1)

- R-D-R-P-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 13, 2017)Document19 pagesR-D-R-P-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 13, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Naser Noaman Mohamed Al Maotari, A077 251 699 (BIA June 2, 2017)Document6 pagesNaser Noaman Mohamed Al Maotari, A077 251 699 (BIA June 2, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Alain Patrana, A025 441 027 (BIA Dec. 22, 2014)Document10 pagesAlain Patrana, A025 441 027 (BIA Dec. 22, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Hemantkumar Patel, A047 463 053 (BIA Sep. 27, 2011)Document2 pagesHemantkumar Patel, A047 463 053 (BIA Sep. 27, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Gzim Imeri, A091 298 819 (BIA July 31, 2013)Document8 pagesGzim Imeri, A091 298 819 (BIA July 31, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Ernesto Villazana-Banuelos, A037 837 474 (BIA June 25, 2013)Document20 pagesErnesto Villazana-Banuelos, A037 837 474 (BIA June 25, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Trinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Document13 pagesTrinath Chigurupati, A095 576 649 (BIA Oct. 26, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Guadalupe Ramirez Moran, A095 445 013 (BIA Dec. 18, 2014)Document10 pagesGuadalupe Ramirez Moran, A095 445 013 (BIA Dec. 18, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- N-V-, AXXX XXX 550 (BIA Nov. 18, 2014)Document3 pagesN-V-, AXXX XXX 550 (BIA Nov. 18, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Jose Lopez-Guerra, A205 659 456 (BIA Jan. 7, 2016)Document13 pagesJose Lopez-Guerra, A205 659 456 (BIA Jan. 7, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Hiep Thanh Nguyen, A073 306 230 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Document10 pagesHiep Thanh Nguyen, A073 306 230 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Tenisini Taufalele, A200 673 398 (BIA Feb. 5, 2016)Document13 pagesTenisini Taufalele, A200 673 398 (BIA Feb. 5, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- M-J-R-, AXXX XXX 084 (BIA May 17, 2017)Document15 pagesM-J-R-, AXXX XXX 084 (BIA May 17, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Tabassum Saleheen, A097 967 736 (BIA July 20, 2009)Document8 pagesTabassum Saleheen, A097 967 736 (BIA July 20, 2009)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Amos Zeith Benka Coker, A056 082 534 (BIA April 28, 2017)Document10 pagesAmos Zeith Benka Coker, A056 082 534 (BIA April 28, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Otoniel Rincon-Velasquez, A089 284 279 (BIA Oct. 21, 2015)Document5 pagesOtoniel Rincon-Velasquez, A089 284 279 (BIA Oct. 21, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Francisco Onate-Vazquez, A079 362 130 (BIA April 14, 2011)Document6 pagesFrancisco Onate-Vazquez, A079 362 130 (BIA April 14, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Alejandro Hernandez-Garcia, A091 097 894 (BIA March 10, 2011)Document3 pagesAlejandro Hernandez-Garcia, A091 097 894 (BIA March 10, 2011)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Ramiro Bravo Nolasco, A205 854 686 (BIA Sept. 10, 2015)Document7 pagesRamiro Bravo Nolasco, A205 854 686 (BIA Sept. 10, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Manuel Jesus Olivas-Matta, A021 179 705 (BIA Aug. 9, 2010)Document25 pagesManuel Jesus Olivas-Matta, A021 179 705 (BIA Aug. 9, 2010)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Imran Wahid, A047 700 704 (BIA July 1, 2015)Document14 pagesImran Wahid, A047 700 704 (BIA July 1, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Craig Hanush Thompson, A044 854 402 (BIA Oct. 1, 2014)Document12 pagesCraig Hanush Thompson, A044 854 402 (BIA Oct. 1, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Moises Martinez-Hernandez, A089 476 569 (BIA Jan. 31, 2012)Document3 pagesMoises Martinez-Hernandez, A089 476 569 (BIA Jan. 31, 2012)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Roxana Guadalupe Galindez Villalba Garriga, A099 163 817 (BIA July 18, 2017)Document6 pagesRoxana Guadalupe Galindez Villalba Garriga, A099 163 817 (BIA July 18, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- S-F-Z-M-, AXXX XXX 301 (BIA July 19, 2017)Document6 pagesS-F-Z-M-, AXXX XXX 301 (BIA July 19, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Ruben Aviles-Diaz, A097 869 352 (BIA Dec. 5, 2013)Document12 pagesRuben Aviles-Diaz, A097 869 352 (BIA Dec. 5, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- D-G-, Axxx xx5 108 (BIA Jan. 28, 2014)Document3 pagesD-G-, Axxx xx5 108 (BIA Jan. 28, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- E-C-N-, AXXX XXX 788 (BIA Oct. 13, 2017)Document8 pagesE-C-N-, AXXX XXX 788 (BIA Oct. 13, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- D-M-A-, AXXX XXX 210 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document9 pagesD-M-A-, AXXX XXX 210 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Anabela Godinez-Perez, A208 202 259 (BIA Jan. 31, 2017)Document6 pagesAnabela Godinez-Perez, A208 202 259 (BIA Jan. 31, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- W-A-D-C-, AXXX XXX 861 (BIA Oct. 6, 2017)Document5 pagesW-A-D-C-, AXXX XXX 861 (BIA Oct. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Carlos Alberto Zambrano, A088 741 973 (BIA Sept. 5, 2014)Document3 pagesCarlos Alberto Zambrano, A088 741 973 (BIA Sept. 5, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Gregoria Saucedo, A201 216 144 (BIA May 8, 2017)Document9 pagesGregoria Saucedo, A201 216 144 (BIA May 8, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Luis Miguel Ramirez-Moz, A072 377 892 (BIA Mar. 31, 2014)Document9 pagesLuis Miguel Ramirez-Moz, A072 377 892 (BIA Mar. 31, 2014)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- J-R-M-, AXXX XXX 312 (BIA April 24, 2015)Document3 pagesJ-R-M-, AXXX XXX 312 (BIA April 24, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- M-J-M-, AXXX XXX 313 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document6 pagesM-J-M-, AXXX XXX 313 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- S-A-M-, AXXX XXX 071 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Document9 pagesS-A-M-, AXXX XXX 071 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Wilmer Jaldon Orosco, A205 008 796 (BIA Dec. 7, 2017)Document2 pagesWilmer Jaldon Orosco, A205 008 796 (BIA Dec. 7, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Kyung Lee, A071 523 654 (BIA Dec. 7, 2017)Document3 pagesKyung Lee, A071 523 654 (BIA Dec. 7, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- C-P-O-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 2, 2015)Document3 pagesC-P-O-, AXXX XXX 486 (BIA Nov. 2, 2015)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Roman Kuot, A094 584 669 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Document9 pagesRoman Kuot, A094 584 669 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Eh Moo, A212 085 801 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Document13 pagesEh Moo, A212 085 801 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- M-F-A-, AXXX XXX 424 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document6 pagesM-F-A-, AXXX XXX 424 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- O-P-S-, AXXX XXX 565 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Document2 pagesO-P-S-, AXXX XXX 565 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Edwin Carrillo Mazariego, A208 023 110 (BIA Dec. 5, 2017)Document3 pagesEdwin Carrillo Mazariego, A208 023 110 (BIA Dec. 5, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Omar Urbieta-Guerrero, A076 837 552 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Document11 pagesOmar Urbieta-Guerrero, A076 837 552 (BIA Dec. 6, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Felipe Turrubiates-Alegria, A206 491 082 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document2 pagesFelipe Turrubiates-Alegria, A206 491 082 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Iankel Ortega, A041 595 509 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document11 pagesIankel Ortega, A041 595 509 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Jesus Efrain Jamarillo-Guillen, A099 161 946 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document6 pagesJesus Efrain Jamarillo-Guillen, A099 161 946 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Adrian Arturo Gonzalez Benitez, A208 217 647 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document2 pagesAdrian Arturo Gonzalez Benitez, A208 217 647 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Adan Ricardo Banuelos-Barraza, A206 279 823 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document7 pagesAdan Ricardo Banuelos-Barraza, A206 279 823 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Vivroy Kirlew, A058 906 861 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Document4 pagesVivroy Kirlew, A058 906 861 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- D-M-A-, AXXX XXX 210 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Document9 pagesD-M-A-, AXXX XXX 210 (BIA Dec. 4, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Jesus Humberto Zuniga Romero, A205 215 795 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document6 pagesJesus Humberto Zuniga Romero, A205 215 795 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Marcos Antonio Acosta Quirch, A044 971 669 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document17 pagesMarcos Antonio Acosta Quirch, A044 971 669 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC100% (1)

- Blanca Doris Barnes, A094 293 314 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Document2 pagesBlanca Doris Barnes, A094 293 314 (BIA Dec. 1, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Yovani Antonio Mejia, A094 366 877 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Document10 pagesYovani Antonio Mejia, A094 366 877 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Mario Harold Flores, A043 945 828 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Document5 pagesMario Harold Flores, A043 945 828 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Armando Fernandes-Lopes, A036 784 465 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Document3 pagesArmando Fernandes-Lopes, A036 784 465 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Odalis Vanessa Garay-Murillo, A206 763 642 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Document5 pagesOdalis Vanessa Garay-Murillo, A206 763 642 (BIA Nov. 30, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- M-J-G-, AXXX XXX 861 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Document17 pagesM-J-G-, AXXX XXX 861 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Jose Jesus Trujillo, A092 937 227 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Document9 pagesJose Jesus Trujillo, A092 937 227 (BIA Nov. 29, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1: Discussion ForumDocument7 pagesAssignment 1: Discussion ForumJean Saunders50% (2)

- United States v. Ponzo, 1st Cir. (2017)Document68 pagesUnited States v. Ponzo, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Juveniles On Trial: Mode of Conviction and The Adult Court Sentencing of Transferred JuvenilesDocument24 pagesJuveniles On Trial: Mode of Conviction and The Adult Court Sentencing of Transferred JuvenilesMatt SmithNo ratings yet

- Criminal Investigation NotesDocument28 pagesCriminal Investigation NotesSharry WalsienNo ratings yet

- Termination of Criminal Cases by Nolle Prosequi.Document18 pagesTermination of Criminal Cases by Nolle Prosequi.AnthonioUgoNjokuNo ratings yet

- Ecris Implementation Report enDocument16 pagesEcris Implementation Report enTifui CatalinaNo ratings yet

- Police Memorandum: Jahzeel L Sarmiento, MaedDocument18 pagesPolice Memorandum: Jahzeel L Sarmiento, MaedSophia RamosNo ratings yet

- Cse ListDocument36 pagesCse ListMil Lorono0% (1)

- (CD) People Vs Castillo - G.R. No. 172695 - AZapantaDocument2 pages(CD) People Vs Castillo - G.R. No. 172695 - AZapantaBlopper XhahNo ratings yet

- People vs. CarmenDocument9 pagesPeople vs. Carmenangelufc99100% (1)

- Sac City Woman Found Guilty of Allowing A Dog To Run at Large and Harboring A Vicious DogDocument12 pagesSac City Woman Found Guilty of Allowing A Dog To Run at Large and Harboring A Vicious DogthesacnewsNo ratings yet

- Antiporda Vs Hon. Garchitorena G.R. No. 133289Document3 pagesAntiporda Vs Hon. Garchitorena G.R. No. 133289Jimenez Lorenz0% (1)

- G.R. No. 217972 PP v. DongailDocument14 pagesG.R. No. 217972 PP v. DongailMark Joseph ManaligodNo ratings yet

- MOKHTAR Nullum Crimen Sine LegeDocument15 pagesMOKHTAR Nullum Crimen Sine LegeRoberto Andrés Navarro Dolmestch100% (1)

- Court Observation A Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesCourt Observation A Reaction Papermary grace banaNo ratings yet

- COPA Report On Mendez Family RaidDocument29 pagesCOPA Report On Mendez Family RaidTodd FeurerNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Undertakings Secondment RevisedDocument1 pageAffidavit of Undertakings Secondment RevisedEllie DukeNo ratings yet

- People Vs OlivaDocument1 pagePeople Vs OlivaFVNo ratings yet

- Seth Ramdayal Jat Vs Laxmi Prasad - AIR 2009 SC 2463Document9 pagesSeth Ramdayal Jat Vs Laxmi Prasad - AIR 2009 SC 2463TashuYadavNo ratings yet

- Crim - Law Latest CasesDocument27 pagesCrim - Law Latest CasesMa Jean Baluyo CastanedaNo ratings yet

- Shafer Dqmotion 2524Document229 pagesShafer Dqmotion 2524Lindsey BasyeNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph Merlino A/K/A Skinney Joey Joseph Merlino, 310 F.3d 137, 3rd Cir. (2002)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Merlino A/K/A Skinney Joey Joseph Merlino, 310 F.3d 137, 3rd Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chupeta TranscriptDocument48 pagesChupeta TranscriptRobert MyersNo ratings yet

- Spivey Plea PRDocument3 pagesSpivey Plea PRWDIV/ClickOnDetroitNo ratings yet

- Unilab vs. Isip Objects of SeizureDocument3 pagesUnilab vs. Isip Objects of SeizureRowardNo ratings yet

- Deterrence BriefingDocument12 pagesDeterrence BriefingPatricia NattabiNo ratings yet