Professional Documents

Culture Documents

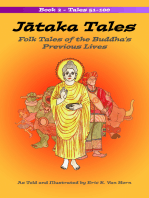

MMilanda Vol 2P Intro Draft 9

Uploaded by

yokkee leong0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views19 pagesQuestions of King Milanda Vol.2

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentQuestions of King Milanda Vol.2

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

111 views19 pagesMMilanda Vol 2P Intro Draft 9

Uploaded by

yokkee leongQuestions of King Milanda Vol.2

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

i

sabbadna dhammadna jinti

The gift of dhamma excels all gifts

Milindapaha Volume 1 & 2 Milindapaha Volume 1 & 2 Milindapaha Volume 1 & 2 Milindapaha Volume 1 & 2

The Questions of King Milinda

(A Book of the Khuddaka Nikya)

The contents of this book may be reproduced either in part or

whole for free distribution, with or without prior consent.

Published and distributed by:

Myanmar-Singapore-Malaysia (MSM) Dhamma Publication

Society (2014).

Private funding by Dhamma Farers in Myanmar, Singapore and

Malaysia.

Edited in Myanmar and Malaysia by:

Dr. Ashin Kumara,

Leong Yok Kee and Carol Law

email: yokkee122@gmail.com

email: punnika68@gmail.com

Book cover design and layout by:

joey.t graphics

www.joeytgraphics.com

This edition May 2014 1,000 sets of 2 volumes

Printed and bound in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by:

Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd.

Tel: +603-4291 6001, +603-4291 6002

Fax: +603-4292 2053

ii

n nn namo tassa bhagavato arahato samm amo tassa bhagavato arahato samm amo tassa bhagavato arahato samm amo tassa bhagavato arahato samm sambudd sambudd sambudd sambuddhassa hassa hassa hassa

Veneration to the Exalted One, the H Veneration to the Exalted One, the H Veneration to the Exalted One, the H Veneration to the Exalted One, the Homage omage omage omage- -- -worthy O worthy O worthy O worthy One, ne, ne, ne,

t tt the Perfectly he Perfectly he Perfectly he Perfectly S SS Self elf elf elf- -- -enlightened O enlightened O enlightened O enlightened One ne ne ne

The Buddha is Supreme.

He is an Arahant, worthy of the highest veneration.

He has extinguished all defilements;

He is perfectly self-enlightened through

realisation of the Four Ariya Truths;

He is endowed with the six great qualities of glory:

issariya, dhamma,

yasa, sir,

kma and payatta.

Brahms, devas and all beings venerate the Buddha.

iii

MAIN MAIN MAIN MAIN CONTENT CONTENT CONTENT CONTENTS SS S

Publishers Introduction v

Prefatory Note xi

Publishers Editorial Note xiii

Introduction by Dr. Ashin Kumara xv

Previous Works on the Subject xviii

Volume I Volume I Volume I Volume I

Preamble 3

Division I: Division I: Division I: Division I: bhirakath bhirakath bhirakath bhirakath - -- - Background history Background history Background history Background history 7

pubbayogdi - Connections in the past 8

Division II: Division II: Division II: Division II: 38

Chapter 1: mahvagga - The great chapter 39

Chapter 2: addhnavagga - The long journey 70

Chapter 3: vicravagga - Discursive thoughts 89

Division III: Division III: Division III: Division III: 114

Chapter 4: nibbnavagga - The deathless realm 115

Chapter 5: buddhavagga - Pertaining to the Buddha 128

Chapter 6: sativagga - On mindfulness 136

Chapter 7: ar|padhammavavatthnavagga-

On mental phenomena 146

milindapahapucchvisajjan -

Questions of King Milinda and answers thereof 165

Division IV: Division IV: Division IV: Division IV: meakapaha meakapaha meakapaha meakapaha - -- - Question on dilemmas Question on dilemmas Question on dilemmas Question on dilemmas 168

Chapter 1: iddhibalavagga - Spiritual and

supernatural powers 180

Chapter 2: abhejjavagga - On schism 250

Chapter 3: pamitavagga - On bowing 276

Chapter 4: sabbautaavagga - On omniscience 307

Chapter 5: santhavavagga - On companionship 341

iv

Volume II Volume II Volume II Volume II

Division Division Division Division V: anumnapaha V: anumnapaha V: anumnapaha V: anumnapaha - -- - Questions on inference Questions on inference Questions on inference Questions on inference

Chapter 1: buddhavagga - The Buddhas 4

Chapter 2: nippapacavagga - Dhamma that thwarts

the cycle of birth and death 38

Chapter 3: vessantaravagga - King Vessantara 59

Chapter 4: anumnavagga - Inference 122

Division Division Division Division VI: opammakathpaha VI: opammakathpaha VI: opammakathpaha VI: opammakathpaha - -- - The similes The similes The similes The similes 170

mtik 171

Chapter 1: gadrabhavaggam - The ass 175

Chapter 2: samuddavagga - The ocean 191

Chapter 3: pathavvagga - The earth 206

Chapter 4: upacikvagga - The white ant 227

Chapter 5: shavagga - The lion 243

Chapter 6: makkaakavagga - The spider 257

Chapter 7: kumbhavagga - The water-pot 274

Epilogue Epilogue Epilogue Epilogue 285

v

Publishers Introduction Publishers Introduction Publishers Introduction Publishers Introduction

The triumvirate jewel of the Buddhas dhamma is given the

honorific title - Tipiaka, a Pi word meaning three baskets; ti

for three and piaka for basket. The tipiaka is the bulwark that

anchors the Buddhas dhamma; and the fortress within which the

dhamma flowers and brings forth fragrance of the truth to the

world at large. The tipiaka is the ssana; the tipiaka is the icon

of the ssana.

The tipiaka stands enduring and dynamic encompassed by its

three wise guardians: the Vinaya, the Suttanta and the

Abhidhamma. These three are the thrust and the defensive entity

beginning life with the first discourse at the deer park in Isipatana

when the Buddha began turning the wheel of dhamma for the

benefit of the five ascetics and a myriad of brahm, devas and

host of unseen beings. The tipiaka began to build up strength and

substance as the days and months go by. The rules of conduct for

bhikkh| was added on as and when the need arose and finally the

Abhidhamma was expounded in the heavenly realm. Thus was the

tipiaka honed and matured into the enduring triumvirate jewel -

the Triple Gem, which the Buddhas dhamma matured into in the

45 years of the Blessed One bringing the dhamma to an

unenlightened world of distorted conceptions not prepared to

recognise the Truth of its existence.

The Blessed One Himself realised this great failing of ordinary

worldlings when contemplating on His Enlightenment:

But the dhamma that I have realised is indeed profound, subtle

and difficult to comprehend. All beings in the world will not be

able to understand the dhamma as they are grossly overwhelmed

by greed, anger and ignorance. It will be wearisome for me if I

were to expound the dhamma. Reflecting thus, the Buddha was

hesitant to teach the dhamma.

vi

The quintessence of the Vinaya has the disciplinary rules of the

bhikkh| to ensure the proper morality of the sagha, and the

welfare of the bhikkh|.

The quintessence of the Abhidhamma has the 7 books of antiquity

for the education of those ready to accept the supramundane

words of the Buddha.

That leaves the Suttanta which is the variegated structure of the

words of the Buddha that was daily discoursed to all and sundry,

ordained and laity, who were then ready to receive and practise

the Truth.

The Pi term sutta means a thread, a string or a discourse; the

Buddhas discourses form a huge quilted tapestry of sutta. The

dhamma message is weaved strand by strand, thread by thread

onto the multi-weaved fabric that stands as a complete edifice; a

network that inclines and tapers into freedom from suffering,

never to find rebirth into another existence whatsoever.

To gain this total freedom from suffering or in Pi, dukkha,

academic studies and absorption of knowledge into the fibres of

our mental potentialities is insufficient effort. In the long term,

this insufficiency of effort will degenerate into wrong effort. Too

much energy expanded into pure academic studies will engender a

sense of superiority in the individual and retards the development

of wisdom.

The Buddha in His great wisdom and knowledge has not only

given us the basis to understand and realise the inherent failings

in us, but also the means to apply one, sole physical practice to

attain to the state wherein we will surely remove all defilement

from our kamma and escape the round of rebirth in totality.

vii

ekyano aya, bhikkhave, maggo sattna visuddhiy

sokapariddavna samatikkamya dukkhadomanassna

attha~gamya yassa adhigamya nibbnassa sacchikiriyya,

yadida cattro satipahna.

This is the only way, bhikkh|, for the purification of beings, for

the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the disappearance

of pain and grief, for reaching the noble path, for the realisation

of nibbna, namely: the four foundations of mindfulness.

The knowledge embedded within the expansive stratospheric

reach of the tipiaka is beyond conceptual realisation. The best

illustration to expound the borderless jurisdiction of the tipiaka is

in the simile of the leaves of the trees in the forest.

A Handful of Leaves A Handful of Leaves A Handful of Leaves A Handful of Leaves

The Blessed One was once living at Kosambi in a wood of

Sisap trees. He picked up a few leaves in his hand, and

questioned the bhikkh|: How do you conceive this, bhikkh|,

which is more, the few leaves that I have picked up in my hand or

those on the trees in the wood?

The leaves that the Blessed One has picked up in His hand are

few, Lord; those in the wood are far more.

So too, bhikkh|, the things that I have known by direct

knowledge are more; the things that I have told you are only a

few. Why have I not told them? Because they bring no benefit, no

advancement in the Holy Life, and because they do not lead to

dispassion, to fading, to ceasing, to stilling, to direct knowledge,

to enlightenment, to nibbna. That is why I have not told them.

viii

And what have I told you? This is suffering; this is the origin of

suffering; this is the cessation of suffering; this is the way leading

to the cessation of suffering. That is what I have told you. Why

have I told it? Because it brings benefit, and advancement in the

Holy Life, and because it leads to dispassion, to fading, to

ceasing, to stilling, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to

nibbna. So bhikkh|, let your task be this: this is suffering; this is

the origin of suffering; this is the cessation of suffering; this is

the way leading to the cessation of suffering.

(Sayutta Nikya, 56:31)

To gain good results from any form of activities, be it education,

the sports, the arts, philosophies, spiritual studies, even skills such

as cooking, wood-work, metal work, silver work, gold craft, etc.,

one needs a suitable medium or base to work from, a platform to

operate from.

The platform from which the multi-faceted knowledge of the

tipiaka can be garnered is the four foundations of mindfulness -

satipahna.

The goad, the springboard, the catalyst, the platform, the carriage,

etc., for the realisation of the knowledge from the tipiaka is an

experiential training in the form of the practice of satipahna.

Make no mistake, though, the way of satipahna is not an easy

way! But it is the Only way for the overcoming of sorrow and

lamentation, for the disappearance of pain and grief, for reaching

the noble path, for the realisation of nibbna.

The Blessed One in most cases when He dismisses listeners at the

end of any discourse, be they ordained or lay, admonishes thus:

These are the roots of trees, bhikkh|, these are empty huts,

meditate, do not be negligent; lest you regret it later.

ix

The final goal of the practice of satipahna is the attainment of

enlightenment and the usual statement to indicate that a

practitioner has achieved that freedom is stated as: obtained the

pure and spotless eye of the truth (that is, the knowledge).

Whatsoever is subject to the condition of origination is subject

also to the condition of cessation.

The study of the questions of King Milinda cannot stand alone as

a complete knowledge ending the quest for the realisation of the

dhamma. It is only one well-oiled cog amongst all the different

parts and parcels that make up the wheel of dhamma; just as the

chariot has its parts and a living being has its aggregates, so the

dhamma, too, has a myriad of sutta: long ones, medium lengths

and minor ones to complete the whole.

In the midst of a persons journey towards the dhamma most

desired fruit, it is imperative that he must face up to the trials and

teachings in the satipahna; failing which his attainment of any

dhamma knowledge will backslide and be reduced to zero.

To be able to begin our investigation of the Buddhas dhamma

with the Milindapaha is the correct and meritorious step towards

the goal of emancipation; for within its pages are the gems and

jewels that will lead the dhamma seeker onwards to the

enlightened purity of nibbna.

The consequential path from this will be the sole diligent practice

of satipahna, leaving all others behind. This will enhance the

seekers knowledge and wisdom, thereby eradicating his

ignorance and developing his insight leading onto the

supramundane knowledge essential for the attainment of

cessation.

x

Most seekers are content and feel gratified that they have in their

portfolio of dhamma studies all the necessary academic literature,

including the nikya and even the Milindapaha! Not to seek and

experience the correct practice is akin to doing things half way;

just as water cannot boil if the power is switch off half way or

rice cannot be eaten if not cooked to its maximum for the

goodness to surface. Academic quests are just that, it is the

acquisition of mundane knowledge. To realise the reality of the

Buddhas dhamma, one needs to go the extra mile; that extra mile

in the case of the dhamma is the supramundane experience.

A dictionary has all the words necessary for you to write a book,

the dictionary cannot write a book; you have to know the words

from the dictionary and then you can string those words into lines

of sentences. The dictionary teaches you the words, you apply the

words to bring out the whole book! Just so, the Buddhas words

are to give you knowledge, you have to string those knowledge

together to find the path that will lead you to supramundane

experiences; and the tool to string the Buddhas words together is

the practice of satipahna.

As the Buddha exhorts, we too exhort; there are trees and

secluded places, dear friends, practise vipassan meditation, do

not neglect, lest you end up in undesirable realms.

Dr. Ashin Kumara

Leong Yok Kee

Carol Law Mi-Lan

xi

Prefatory Note Prefatory Note Prefatory Note Prefatory Note

The Milindapaha in the Theravda tradition, is regarded highly

as a book of authority and has long been a popular piece of

literature in the Pi form; and at the Chahasa~gti Pitaka (the

Sixth Buddhist Council) held in Yangon, 1954, the Milindapaha

was formally included as the 18

th

book in a list of 18 books in the

Khuddaka Nikya according to the Burmese tradition.

The Milindapaha seek to introduce and at the same time clarify

fundamental points in the Teaching of the Buddha. It does so in a

simple question and answer dialogue between two highly placed

personality so that it has the authority of royalty in the

questioning and a very knowledgeable arahant in the clear

answers. The raison detre of the dialogue is clear; royalty to

commoner will benefit from the dhamma! Thus, the questioner

was a Greek king; King Menander or Milinda and the answers

presented by the bhikkhu, Ngasena, an arahant.

The questions brought to our attention by the king and the

solutions discussed and offered by the arahant Ngasena pinpoint

the basic tenets which form the cornerstone of the Buddhas

sublime Teaching.

The succinct and factual answers presented by the arahant

Ngasena, in most cases complemented by similes and examples,

eloquently propounded and in an easy grace of dialogue, mostly,

though not always, truly appeals to the discerning seeker of the

Buddhas dhamma.

There were occasions when Ngasena, not too happy with the

quality of questions raised by the king, replied testily.

xii

It is no doubt that it is the charm of this style and the profound

nature of the answers that has drawn many to see in the

Milindapaha, an all-encompassing showcase of the Buddhas

Teaching, in a nutshell as it were.

May the transcendent Teaching of the Blessed One that is

available to us today, enrich and enlighten those who continue to

investigate and practise the dhamma.

Carol Law

xiii

Publisher Publisher Publisher Publishers ss s Editorial Not Editorial Not Editorial Not Editorial Notes es es es

The first known English translation of the Milindapaha was

possibly one done by T.W. Rhys Davids, published about 120

years ago. There is no doubt how popular and widely sought after

the Milindapaha is, judging by its translations available today in

English, French, German, Russian, Burmese, Chinese, Japanese,

Hindi, Sinhalese, Sanskrit and so forth.

In our preparation of this set of two volumes, we were privileged

to have in our hands a copy of the English translation from the

Pi and Burmese versions, as well as many books that form the

basis of our reference and research.

The style adopted in this classic prose is essentially that of a

dialogue between two people: King Milinda and the Venerable

Ngasena. We have thus used abbreviations to indicate the direct

speeches of these two people km km km km for King Milinda and vn vn vn vn for

Venerable Ngasena. We believe this makes for an easier and a

more enjoyable read.

In attempting to keep to the proper presentation of the words in

the Pi form, these terms are written with small letters, as in the

tradition of the language. Capital letters are not used for Pi

words even when it is the start of a sentence. The exception is

made for proper nouns to distinguish them as terms used with

reference to the Buddha and names of people and places.

As the illustrious conversations between the king and the

venerable ran well over 700 pages, we thought it best that the

book be presented in two volumes. Volume I houses divisions I to

IV while Volume II concludes the rest of the discussion with

divisions V and VI.

xiv

In this way, the readers hands are not strained with cradling a

massive book, or the shoulders burdened with the extra weight

should he wish to bring it around with him. Of course, to match

the respect and prestige the Milindapaha holds, the two volumes

are presented to you, encased in an elegant magnetic box jacket,

specially designed to keep the books together.

In the rendition of a somewhat lengthy text, readers may find

themselves lost in the labyrinth of topics and dilemmas covered

therein. By introducing a detailed sub-content page at the start of

each chapter, our goal is to put in better perspective, the main

sections from the sub-sections. Hopefully our reader will find this

a useful as well as an effective tool as they navigate through the

eclectic book.

In closing, the editors would like to put on record, their expressed

gratitude in being called to such a noble and onerous undertaking.

It is their wish that in their humble endeavour to refine the

presentation of this essential dhamma literature so that many

more will glean from it the goodness of the profound Teaching of

the Buddha within. May the ssana endure, may the pristine

dhamma prevail.

Dr. Ashin Kumara

Leong Yok Kee

Carol Law

xv

Introd Introd Introd Introduction uction uction uction by by by by Dr. Ashin Kumara Dr. Ashin Kumara Dr. Ashin Kumara Dr. Ashin Kumara

Siddhattha Gotama was born in 623 B.C., renounced family life,

the life of a prince at the prime of a youths life, 29 years of age.

He renounced the luxurious life of royalty and donning the cast-

off robes befitting a homeless renunciate; deeply aware of the

sorrows of existence in a world led by mindless desires; with firm

steps and purposeful determination, he went in search of the

Truth. Through 6 years of life and death struggles, nearing death

more than not, He achieved the Supreme state of Buddhahood at

the age of 35 and attained parinibbna at the age of 80 (543 B.C.).

For 45 years after attaining Buddhahood, He steadfastly, without

a care for His own comfort, toured the country, especially the

North-eastern part of India, expounding the sutta, abhidhamma

and the vinaya to gods and men.

The principles, laws and disciplines for monastic life are

enshrined in the Vinaya Disciplinary Rules; Sutta form the basis

for daily practice and the Abhidhamma holds the knowledge of

the Buddhas philosophy and psychology.

Long after the Buddha attained parinibbna, the vinaya rules, the

dhamma in the form of sutta and abhidhamma still exist as a

teacher for a wholesome and moralistic life. As long as they still

exist, we can be sure that we still have the Buddha in our midst.

The Buddha taught the dhamma to all, regardless of gender, age

or stations in life, so that the truth of their existence will be

understood by them. He also encouraged those who wish to take

up the Holy Life that they adhere to strict rules, so that they may

co-exist in harmony with other fellow human beings and practise

to gain penetrative wisdom into the knowledge of ultimate reality

as enshrined in the tipiaka.

xvi

The whole of the teachings of the Buddha are collectively known as

the Three Baskets or tipiaka. As such, the tipiaka has taken on

the essence of the Buddha Himself and now becomes our teacher

and mentor.

Three months after the Buddhas parinibbna, a Great Council of

the arahant theras was convened led by the Elder Mah Kassapa.

The Council held in Rjagaha was attended by 500 arahants. At

the conclusion of this lengthy Great Council, the arahant theras,

of whom the Elder Mah Kassapa was the leader, made three

irrevocable stipulations. That henceforth, the teachings of the

Buddha as confirmed in this Council, should be kept strictly to the

word, letter and intent.

Thus, there should be no addition to the words, no deletion and

the format presented here should remain as it is. Therefore, this

Council set the tone of the tradition that is kept intact until today.

This knowledge, belief and practice that are strictly in accordance

with the dhamma and vinaya of the Buddha are known as the

teachings of the elders or theravda dhamma and vinaya.

The Second Council, headed by Sabbakmi Thera and Yasa

Thera, was held in 100 B.E. (Buddhist Era) in Vesl and was

attended by 700 monks.

The Third Council headed by Tissa Thera took place in 236 B.E.

in Paaliputta and was attended by 1,000 monks. The First, Second

and Third Councils were the only councils held in India and all

the participants were arahants.

The Fourth Council led by the Venerable Dhammarakkhita,

attended by 500 Sri Lankan monks was held in Sri Lanka in 540

B.E. At this Council, the words of the tipiaka was engraved and

preserved onto palm leaves.

xvii

In 2400 B.E., the Fifth Council led by the Venerable Jgara Thera

and attended by 2,400 monks was held in Mandalay, Burma. At

this Council, the tipiaka was inscribed onto 729 marble slabs,

each measuring 6 feet by 4 feet. These can still be seen today at

the Maha Lokamarazein Kuthodaw Pagoda, Mandalay Hills.

The Sixth Council, sponsored by the Burmese Government, was

held in 2498 B.E (May, 1954) in Kaba-Aye, Yangon, Myanmar, at

the Mahpsna Great Cave (a duplicate of the original cave of

the First Council). The Council took two years to conclude its

mission. The unique feature of the Sixth Council was the

participation by learned monks from five Theravda and some

Mahyana countries.

Present day literature that attempts to explain the Buddhas

Teaching are merely the interpretation of various authors in their

limited knowledge and understanding of the true dhamma. They

act only as a secondary source of information to the profound

Teaching. For those who have not acquired the genuine essence

of the authentic and pristine Teaching of the Buddha from true

sources and not knowing the true dhamma is indeed, a great loss

to them.

May the knowledge, belief and practice of the Truth shine forth

in every corner of our world.

Dr. Ashin Kumara

xviii

Previous Previous Previous Previous W WW Works on the orks on the orks on the orks on the S SS Subject ubject ubject ubject

The Pi Milindapaha and its Chinese counterpart, Na-hsien-pi-

ch'iu-ching have enjoyed much popularity among Western and

Eastern scholars, and numerous are the translations of the two

above texts into various languages. Some of these translations are

mentioned below:

1. Louis Finot: Les Questions de Milinda, Paris 1923 (French

translation of Books I-III).

2. T.W. Rhys Davids: The Questions of King Milinda (English

translation from the Pi, 1890)

3. Nynatiloka: Fragen des Milinda, Munchen 1919 (Complete

German translation).

4. F. Otto Schrader: Die Fragen des Konigo Menandros, Berlin

1905 (German translation of the portions held to be original

by the translator).

5. Specht and Levi: Deux traductions chinoises de

Milindapaho: Oriental Congress IX, London, 1892, Vol. I,

p.518ff.

6. Sogen Yamagami: Sutra on Questions of King Milinda

(Japanese translation from the Chinese text).

7. Sei Syu Kanamoli: Questions of King Milinda (Japanese

translation from the Pi text).

8. Paul Demieville: Les versions Chinoises du Milindapaha,

BEFEO, Vol. XXIV, 1924.

Dissertations on the two Pi and Chinese texts, and

comparative studies of them have captured the attention of

many learned pait. Some of these dissertations and

comparative studies are cited below:

1. Garbe: Beitrge zur indischen Kulturgeschichte Belin, 1903.

2. Mrs C.A.F. Rhys Davids: The Milinda Question, London

1930.

xix

3. T.W. Rhys Davids: Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics,

Vol. VIII, p.631ff., article on "Milindapaho"

4. Taisho edition of the Chinese Tripitaka edited by Takakusu

and Watanabe, Vol.32, No.1670 (a&b).

5. Winternitz: History of Indian Literature, Vol. II, pp.174-183.

6. Siegfried Behrsing, Beitrage zu einer, Milinda Bibliographie,

Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, Vol. VII, 3.

pp.516ff.

7. B. C. Law: A History of Pi Literature Vol. II, pp. 353-72.

8. J. Takakusu: Chinese Translations of the Milindapaha

JRAS, 1896.

9. Dr. Kogen Mizuno: On the Recensions of Milindapaho.

You might also like

- The Word Of The Buddha; An Outline Of The Ethico-Philosophical System Of The Buddha In The Words Of The Pali Canon, Together With Explanatory NotesFrom EverandThe Word Of The Buddha; An Outline Of The Ethico-Philosophical System Of The Buddha In The Words Of The Pali Canon, Together With Explanatory NotesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Stilling the Mind: Shamatha Teachings from Dudjom Lingpa's Vajra EssenceFrom EverandStilling the Mind: Shamatha Teachings from Dudjom Lingpa's Vajra EssenceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Core Teachings of Kagyu School MahamudraDocument10 pagesCore Teachings of Kagyu School MahamudraGediminas GiedraitisNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's HandbookFrom EverandMindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's HandbookRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (25)

- Vipassana Dipani (By Ledi Sayadaw)Document44 pagesVipassana Dipani (By Ledi Sayadaw)api-3728716No ratings yet

- The Smokeless Fire: Unravelling The Secrets Of Isha, Kena & Katha UpanishadsFrom EverandThe Smokeless Fire: Unravelling The Secrets Of Isha, Kena & Katha UpanishadsNo ratings yet

- 04 Anapanasati Sutta PDFDocument11 pages04 Anapanasati Sutta PDFmarcos.peixotoNo ratings yet

- Significance of Four Noble TruthsDocument22 pagesSignificance of Four Noble TruthsBuddhist Publication SocietyNo ratings yet

- The Collected Works of ShinranDocument472 pagesThe Collected Works of ShinranAlexandros Pefanis100% (1)

- The Manual of InsightDocument75 pagesThe Manual of InsightJack FooNo ratings yet

- The Buddha Re-DiscoveredDocument185 pagesThe Buddha Re-DiscoveredMario Galle MNo ratings yet

- The Abhidhamma in Practice - N.K.G. MendisDocument54 pagesThe Abhidhamma in Practice - N.K.G. MendisDhamma Thought100% (1)

- The Chakrasamvara Root Tantra: The Speech of Glorious HerukaFrom EverandThe Chakrasamvara Root Tantra: The Speech of Glorious HerukaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Mind of Mahamudra: Advice from the Kagyu MastersFrom EverandMind of Mahamudra: Advice from the Kagyu MastersNo ratings yet

- Exegetical 8Document5 pagesExegetical 8Fussa DhazaNo ratings yet

- Enlightenment to Go: Shantideva and the Power of Compassion to Transform Your LifeFrom EverandEnlightenment to Go: Shantideva and the Power of Compassion to Transform Your LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Journey to Certainty: The Quintessence of the Dzogchen View: An Exploration of Mipham's Beacon of CertaintyFrom EverandJourney to Certainty: The Quintessence of the Dzogchen View: An Exploration of Mipham's Beacon of CertaintyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Know Where You're Going: A Complete Buddhist Guide to Meditation, Faith, and Everyday TranscendenceFrom EverandKnow Where You're Going: A Complete Buddhist Guide to Meditation, Faith, and Everyday TranscendenceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Practicing Wisdom: The Perfection of Shantideva's Bodhisattva WayFrom EverandPracticing Wisdom: The Perfection of Shantideva's Bodhisattva WayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- The Crest-Jewel of Wisdom: And other writings of SankaracharyaFrom EverandThe Crest-Jewel of Wisdom: And other writings of SankaracharyaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Treasure of the Profound Path: A Word-by-Word Commentary on the Kalachakra Preliminary PracticesFrom EverandHidden Treasure of the Profound Path: A Word-by-Word Commentary on the Kalachakra Preliminary PracticesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- MP Book 2 Draft 9Document289 pagesMP Book 2 Draft 9yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita — A New Translation and Commentary, Chapters 1–6From EverandMaharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita — A New Translation and Commentary, Chapters 1–6No ratings yet

- Religious Experience On Buddhism BarnesDocument11 pagesReligious Experience On Buddhism BarnesBharat DevanaNo ratings yet

- Homage To The 28 BuddhasDocument42 pagesHomage To The 28 BuddhasSujeewa Gunasinghe100% (1)

- Kapila Dev Glories - HVDDocument8 pagesKapila Dev Glories - HVDmaverick6912No ratings yet

- An Overview of The Triple VisionDocument32 pagesAn Overview of The Triple Visionthinh.academiavnNo ratings yet

- Ornament to Beautify the Three Appearances: The Mahayana Preliminary Practices of the Sakya Lamdré TraditionFrom EverandOrnament to Beautify the Three Appearances: The Mahayana Preliminary Practices of the Sakya Lamdré TraditionNo ratings yet

- The Tantric Distinction: A Buddhist's Reflections on Compassion and EmptinessFrom EverandThe Tantric Distinction: A Buddhist's Reflections on Compassion and EmptinessNo ratings yet

- Apannaka Sutta, Cula Malunkya Sutta, Upali SuttaDocument37 pagesApannaka Sutta, Cula Malunkya Sutta, Upali SuttaBuddhist Publication SocietyNo ratings yet

- Unravelling The Mysteries of Mind and Body Through AbhidhammaDocument157 pagesUnravelling The Mysteries of Mind and Body Through AbhidhammaTanvir100% (3)

- Vipassana DipaniDocument42 pagesVipassana DipaniTisarana ViharaNo ratings yet

- BM#6 Not Only SufferingDocument58 pagesBM#6 Not Only SufferingBGF100% (1)

- Summary of Nyanaponika & Hellmuth Hecker's Great Disciples of the BuddhaFrom EverandSummary of Nyanaponika & Hellmuth Hecker's Great Disciples of the BuddhaNo ratings yet

- 4 Noble TruthsDocument70 pages4 Noble TruthsDarnellNo ratings yet

- The Way of Buddhist MeditationDocument82 pagesThe Way of Buddhist Meditationpatxil100% (1)

- Buddhist Meditation and Its Forty SubjectsDocument28 pagesBuddhist Meditation and Its Forty SubjectsQiyun WangNo ratings yet

- Dharma EssentialDocument29 pagesDharma EssentialBai HenryNo ratings yet

- The Wheel of Birth and DeathDocument33 pagesThe Wheel of Birth and DeathabrahamzapruderNo ratings yet

- Sa 379Document33 pagesSa 379Rob Mac HughNo ratings yet

- Jnana Sankalini Tantra Paramahansa Prajnanananda - TextDocument251 pagesJnana Sankalini Tantra Paramahansa Prajnanananda - TextAnonymous Mkk75e100% (6)

- Buddhist Attitude To EducationDocument7 pagesBuddhist Attitude To EducationKarbono AdisanaNo ratings yet

- Milindapanha Vol.1Document372 pagesMilindapanha Vol.1yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- MP Book 2 Draft 9Document289 pagesMP Book 2 Draft 9yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Milindapanha Vol.1Document372 pagesMilindapanha Vol.1yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- The Buddha Re-DiscoveredDocument185 pagesThe Buddha Re-DiscoveredMario Galle MNo ratings yet

- MMilanda Vol 2P Intro Draft 9Document19 pagesMMilanda Vol 2P Intro Draft 9yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Progress of Spiritual InsightDocument154 pagesProgress of Spiritual Insightyokkee leong100% (1)

- MP Book 2 Draft 9Document289 pagesMP Book 2 Draft 9yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Milindapanha Vol.1Document372 pagesMilindapanha Vol.1yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Four Discourses On KammaDocument47 pagesFour Discourses On Kammayokkee leong100% (1)

- Kamma & RebirtrhDocument61 pagesKamma & Rebirtrhyokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The DhammaDocument35 pagesThoughts On The Dhammakosta22No ratings yet

- Vipassana Mindfulness MeditationDocument157 pagesVipassana Mindfulness Meditationyokkee leong100% (7)

- Striving To Be A NobodyDocument172 pagesStriving To Be A Nobodyyokkee leong75% (4)

- Window To The SuttasDocument193 pagesWindow To The Suttasyokkee leong100% (1)

- Vipassana - BasicDocument94 pagesVipassana - Basicyokkee leongNo ratings yet

- The Sixteen Dreams 2Document120 pagesThe Sixteen Dreams 2yokkee leongNo ratings yet

- On SelflessnessDocument151 pagesOn Selflessnessyokkee leongNo ratings yet

- The Ancient Thera CouncilsDocument125 pagesThe Ancient Thera Councilsyokkee leongNo ratings yet

- Samatha Vipassana YuganaddhaDocument211 pagesSamatha Vipassana Yuganaddhayokkee leongNo ratings yet

- The Buddha Re-DiscoveredDocument185 pagesThe Buddha Re-DiscoveredMario Galle MNo ratings yet

- Arousing of InsightDocument120 pagesArousing of Insightyokkee leong100% (1)

- Planes of RebirthDocument104 pagesPlanes of Rebirthyokkee leongNo ratings yet

- The Space of SilenceDocument7 pagesThe Space of SilenceRounak FuleNo ratings yet

- Lab ReportDocument6 pagesLab ReportAnnie Jane SamarNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Symbols and Figurative Language To Reveal The Theme in Do Not Go Gentle by Dylan ThomasDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Symbols and Figurative Language To Reveal The Theme in Do Not Go Gentle by Dylan ThomasShantie Ramdhani100% (1)

- Vagbhatananda: Social Reformer and Spiritual LeaderDocument47 pagesVagbhatananda: Social Reformer and Spiritual LeaderVipindasVasuMannaatt100% (1)

- 3.3 Knowledge RepresentationDocument4 pages3.3 Knowledge RepresentationFardeen AzharNo ratings yet

- Remains of the Day Suez CrisisDocument2 pagesRemains of the Day Suez CrisisCecilia KennedyNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Accounting EducationDocument20 pagesEthics in Accounting EducationElisabeth AraújoNo ratings yet

- Diferencia Entre Mito y Leyenda 120920181036 Phpapp02 PDFDocument9 pagesDiferencia Entre Mito y Leyenda 120920181036 Phpapp02 PDFHistoria UplaNo ratings yet

- A Walk by Moonlight (Summary)Document3 pagesA Walk by Moonlight (Summary)vasujhawar200179% (28)

- L1 - Basic Concepts of ResearchDocument25 pagesL1 - Basic Concepts of ResearchNoriel Ejes100% (1)

- Archangel Michael Becoming A World Server and Keeper of The Violet FlameDocument7 pagesArchangel Michael Becoming A World Server and Keeper of The Violet FlameIAMINFINITELOVE100% (3)

- Richard AvenariusDocument8 pagesRichard Avenariussimonibarra01No ratings yet

- Neither Physics Nor Chemistry A History of Quantum Chemistry (Transformations Studies in The History of Science and Technology) (PRG)Document367 pagesNeither Physics Nor Chemistry A History of Quantum Chemistry (Transformations Studies in The History of Science and Technology) (PRG)yyyyy100% (1)

- Lesson 6: Major Ethical PhilosophersDocument25 pagesLesson 6: Major Ethical PhilosophersKrisshaNo ratings yet

- TaraBrach - RAIN - A Practice of Radical CompassionDocument2 pagesTaraBrach - RAIN - A Practice of Radical CompassionRahulTaneja100% (2)

- I Have A Dream 1Document3 pagesI Have A Dream 1EmelisaSadiaLabuga46% (13)

- Art Theory Introduction To Aesthetics (Online Short Course) UALDocument1 pageArt Theory Introduction To Aesthetics (Online Short Course) UALKaterina BNo ratings yet

- New Mechanisms and the Enactivist Concept of ConstitutionDocument16 pagesNew Mechanisms and the Enactivist Concept of ConstitutionKiran GorkiNo ratings yet

- Religion Is DangerousDocument7 pagesReligion Is DangerousTimothy ScanlanNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Management Research: An Exploratory Content AnalysisDocument15 pagesThe Ethics of Management Research: An Exploratory Content AnalysisSaravanakkumar KRNo ratings yet

- Brechtova DijalektikaDocument11 pagesBrechtova DijalektikaJasmin HasanovićNo ratings yet

- Module1 ADGEDocument11 pagesModule1 ADGEHersie BundaNo ratings yet

- Iks Adi ShankracharyaDocument11 pagesIks Adi ShankracharyaNiti PanditNo ratings yet

- Livingston Paisley Literature and Rationality 1991Document266 pagesLivingston Paisley Literature and Rationality 1991Dadsaddasdsdsaf SafsggsfNo ratings yet

- Turnbull Life and Teachings of Giordano BrunoDocument114 pagesTurnbull Life and Teachings of Giordano Brunoionelflorinel100% (1)

- Teacher-Centered PhilosophyDocument12 pagesTeacher-Centered PhilosophyXanthophile ShopeeNo ratings yet

- The Picture of Our UniverseDocument34 pagesThe Picture of Our UniverseKavisha Alagiya100% (2)

- Tibetan Developments in Buddhist Logic: Chapter I: The Reception of Indian Logic in TibetDocument84 pagesTibetan Developments in Buddhist Logic: Chapter I: The Reception of Indian Logic in TibetVasco HenriquesNo ratings yet

- Ethics PM Toy CaseDocument7 pagesEthics PM Toy CaseGAYATRIDEVI PAWARNo ratings yet

- Scientific Research in CommunicationDocument10 pagesScientific Research in Communicationmucheuh0% (1)