Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Europeanization and Globalization

Uploaded by

Anonymous 6mLZ4AM1NwCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Europeanization and Globalization

Uploaded by

Anonymous 6mLZ4AM1NwCopyright:

Available Formats

http://cps.sagepub.

com/

Comparative Political Studies

http://cps.sagepub.com/content/34/3/227

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0010414001034003001

2001 34: 227 Comparative Political Studies

DANIEL VERDIER and RICHARD BREEN

Union

Europeanization and Globalization : Politics Against Markets in the European

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at: Comparative Political Studies Additional services and information for

http://cps.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://cps.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://cps.sagepub.com/content/34/3/227.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- Apr 1, 2001 Version of Record >>

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001 Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION

The authors attempt to sort out three exogenous factors affecting the domestic societies of Euro-

pean Union (EU) member countries: market globalization, the European single market, and

European supranational institutions. They offer a research design to separate the respective man-

ifestations of each factor and apply it to four domestic dimensions: labor market, capital market,

electoral competition, and center-local government relations. Although they find systematic evi-

dence in the cases of the labor and capital markets supporting the widely shared claimthat the EU

is an agent of globalization, the results also point to the importance of the voluntarist component

in the electoral and subgovernmental domains.

EUROPEANIZATION

AND GLOBALIZATION

Politics Against Markets

in the European Union

DANIEL VERDIER

RICHARD BREEN

European University Institute

T

he academic debate about European integration no longer bears on

whether there is integration, as it used to until 15 years ago. It also does

not seemto bear on whether the actual agent of this integration is the council,

the commission, or the court. The debate bears, instead, on the mechanism

that is responsible for that integration: Is it the market or the will to build a

polity?

227

AUTHORS NOTE: We thank Geoffrey Garrett, Dennis Quinn, and Duane Swank for supplying

us with some of their data. We thank our colleagues at the European University Institute, Jim

Caporaso, three anonymous reviewers, and Brian McCormack for useful comments. A draft of

this article was presented at the 1999 Meeting of the International Studies Association, Omni

Shoreham, Washington, DC, in February 2000. Correspondence concerning this article should

be addressed to Daniel Verdier, European University Institute, Via dei Roccettini 9, 50016 San

Domenico di Fiesole (FI), Italy.

COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES, Vol. 34 No. 3, April 2001 227-262

2001 Sage Publications, Inc.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

The debate is complicated by global trends. In Europe, as elsewhere, fac-

tor markets are being deregulated, partisan identification is eroding, local

governments are becoming more active, and so forth. Yet from a European

Union (EU) residents perspective, the origins of these ubiquitous changes

are unclear. It is unclear whether they reflect global trends, referred to as

globalization, or the play of forces that are directly attributable to European

integration, Europeanization.

When trying to explain changes in EU countries, therefore, observers are

faced with a trinity of plausible factors: global markets, the single market,

and the political union. Sorting out their respective effects is a daunting task,

to which we give a first crack. We first try to theorize the general implications

of each effect and then empirically test for their actual occurrence. Although

we find evidence supporting the widely shared claim that the EU is an agent

of globalization, our results also point to the importance of the voluntarist

component.

THE QUESTION

European integration can theoretically proceed in two ways. One is the

construction of a single market without a political union. The other way is to

build a political union with a wide range of centralized policies. Although

reality falls somewhere in between these two ideals, political scientists are of

the opinion that European integration as of late has leaned toward market

integration more so than political voluntarism. Apologists praise what

Majone (1996) calls the gradual depoliticization of the Common Market

(p. 330), which has taken common market countries away from planning,

corporatist self-regulation, and the public ownership of natural monopolies

toward the regulation by experts and regulatory commissions of private and

privatized monopolies. Consistent with this line of argument is the creation

of a single currency managed by an independent central bank. Critics alike

lament what Scharpf (1996) and Streeck and Schmitter (1991) call negative

integrationthe practice of striking down national regulation without

replacing it with supranational regulation. The policy of merely purging mar-

kets frombarriers to competition worked because, as Lange (1992) put it with

respect to social policies, There is no compelling need to harmonize social

policies in order for the single market to operate effectively (p. 253). The

outcome is even deemed by some as biased toward big business: Grahl and

Teague (1989) equate European integration with the gradual erosion of

social constraints on the normless self-definition of economic objectives by

the strongest enterprises themselves (p. 50). The only dissenting voice

228 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

comes from two American economists. Alesina and Wacziarg (1999) write

that

Europe is going too far on many issues that would be better dealt with in a

decentralized fashion, while it is not going far enough on policies that guaran-

tee the free operation of market both across and within the countries of the

Union. (p. 3)

Except for these two, the consensus among Europeanists is that EU institu-

tions have promoted an exclusively economic form of integration, doing lit-

tle to construct a centralized system of interest representation and decision

making in a broad range of issuesa polity.

If Europeanization is de facto synonymous with deregulation (or mar-

ket-conforming re-regulation, as Majone, 1996, puts it), then its effects

should be similar to the effects of globalization. The globalization of national

markets is indeed a case of market integration by deregulation, involving the

enlargement of the national market to the global market and requiring no

(inter-)governmental action other than the deregulation and opening of mar-

kets.

1

The deregulatory effects of globalization, presently the object of a

voluminous literature, are commonly said to be four-pronged. We quickly

survey these results, temporarily suspending judgment on their empirical

validity.

First, the openness of product markets intensifies competition between

firms, forcing the path of innovation (see Castells, 1996; M. E. Porter, 1990)

and increasing the instability of input markets, in particular, the labor market

(see Streeck, 1987). The capacity of firms to locate newinvestments in wage

havens makes domestic investment sensitive to domestic wage levels (see

Chase, 1998; Thurow, 1996). Labor instability creates a demand for govern-

ment to insure workers against market risk through unemployment benefits,

government employment, and the provision of assorted social services.

Second, and simultaneously, cross-border capital mobility undermines

the capacity of the government to deliver this much-needed insurance. Capi-

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 229

1. The identity between globalization and market competition is not absolute. Global mar-

kets do not exist in an institutional vacuum but are embedded in NATO, the OECD, the GATT,

the World Trade Organization, and the belief, held by the most advanced countries, in the desir-

ability of trade and financial openness. The difference between these global regimes and the

European Union (EU) is one of degreethe latter has stronger coordination mechanisms than

the former. Because all EUcountries are also members of all global regimes, the potentially spu-

rious impact of global regimes on markets is automatically controlled for, allowing the analysis

to focus on the added impact of EU regional institutions. Furthermore, although some non-EU

countries are also involved in some formof regional organization (European Free Trade Agree-

ment, North American Free Trade Agreement, Mercosur, and so forth), none of these schemes

have reached a level comparable to the EU.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

tal mobility increases the elasticity of the domestic tax base with respect to

the tax rate (see Bates & Da-Hsiang, 1985; Rodrik, 1997; Steinmo, 1993).

Capital mobility also deters governments from financing budget deficits by

printing money or over borrowing (see Kurzer, 1993; Strange, 1986). Which

of these two forcesthe rising demand for public insurance and the sinking

capacity to meet that demandprevails is a priori indeterminate and a matter

for empirical research. Both Garrett (1995, 1998) and Swank (1998) argue

that some of the alleged effects, far from being general, are mediated by

domestic institutions.

Third, as markets are becoming more important, governments are becom-

ing less so. Loyalty to political parties declines, along with voter turnout and

government stability. Politicians are losing the capacity to govern at the same

time as government loses some of its prior relevance to market allocation.

Fourth, greater factor mobility frees up latent economies of agglomera-

tion, causing a territorial relocation of mobile factors away from poor or

declining peripheries to wealthier and upcoming centers (see Fujita,

Krugman, & Venables, 1999; Krugman, 1991). Increasing territorial

inequalities between local jurisdictions raises the demand for offsetting terri-

torial transfers administered by the central government. The capacity of the

central government to supply these transfers, however, is on the decline. Dis-

tricts that win from relocation oppose these transfers (see Bartolini, 1998).

Lower dependence on the national market makes secession a credible threat

(see Alesina &Spolaore, 1997; Bolton, Roland, &Spolaore, 1996). Which of

the two forcesthe increasing demand for offsetting territorial transfers or

the declining supply of such transferswins, here again, seems to be an

empirical matter.

All the presumed effects of globalizationthe emphasis on labor market

flexibility, bank privatization, financial deregulation, low voter turnout,

increasing electoral volatility, the threat of secessionare not unfamiliar to

EUcountries. These similarities fuel the claims of the above-mentioned liter-

ature that Europeanization is globalization by another name. The EU is seen

as a simple agent of globalization or an irrelevant intervening factor. Euro-

pean economies would have reached a qualitatively similar state of market

deregulation by simply exposing themselves to the global winds without

engaging in the costly and painstaking construction of Europe. The commis-

sion is taking the praise (or alternatively, the blame) for an outcome over

which it has limited control.

What would be an alternative to globalization? Assuming for a moment

that Europeanization is not reducible to globalization but that the political

component is as active and as much developed as the market component,

what would Europeanization look like? We venture that the strengthening of

230 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

the political dimension, had it occurred, would translate into the preservation

of the existing (and/or the development of an alternative) interventionist

capability. The reasoning runs like this: Political voluntarism, irrespective of

its substantive goals, is ineffective without a centralized decision-making

process, easing coordination among all interested partiesnot only the

national governments but also a comprehensive system of interest represen-

tation, including the political parties that are temporarily in opposition, trade

associations and trade unions, employers and employees peak associations,

consumers associations, and so forth. The superiority of such a centralized

system of interest representation is its unique capacity to produce policies

that are not enforceable without the consent of the interested parties. The

existence of such a mechanism was found to be essential to the stabilization

of European economies in the wake of the oil shocks.

In the context of the EU, such a centralized and comprehensive deci-

sion-making process can take one of two forms: intergovernmental or fed-

eral. The intergovernmental mode of centralized decision making, the one

that is more prevalent in the present state of bounded federalism, relies on the

maintenance of separate centralized interest representation mechanisms in

each member country and their coordination at the supranational level

through government delegates (the existing Council of Ministers and derived

committees). It is a case in which interest groups and political parties remain

linked to national governments for two reasons. First, these national govern-

ments enjoy veto power within the EU legislative process. Second, the

absence of an EUbudget makes any compensatory policy the province of the

national government. Among the four issue areas that we survey below, this

intergovernmental decision-making process prevails in threelabor market,

financial market, and electoral volatility.

The second type of centralized interest representation is federal. It would

involve the creation of regional forms of interest representation in factor mar-

kets and the politythat is, social corporatism at the unions level in the

labor market, EU-regulated credit allocation in the capital market, disci-

plined parties in the European Parliament, and centralized bureaus in

Brussels. This form of interest representation is unknown to Brussels (see

Streeck & Schmitter, 1991; Turner, 1996). Its closest, yet still far remote,

approximation is the structural funds policy. This is a rare case in which the

EUhas a budget and the commission enjoys some real spending power. Cer-

tainly, governments decide on country quotas; but mutual suspicion, backed

by experience, that funds might be wasted on consumption by national recip-

ients forced governments to establish strict standards on spending, relin-

quishing monitoring to the commission. Governments also agreed to dele-

gate spending authority to subnational jurisdictions and allow direct

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 231

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

bargaining with the commission. The upshot has been the growth of a central-

ized system of subnational interest representation in Brussels (see Marks,

Nielsen, Ray, & Salk, 1997; Smyrl, 1998).

Although these two modes are usually represented as theoretically anti-

thetical (viz. the debate between so-called intergovernmentalists and the

manifold heirs to Haass neofunctionalism), they are both distinct from

integration via market deregulation. Either one could supply European politi-

cal elites with a voluntarist capability, enabling them to pursue outcomes in

concurrence with markets or beyond what markets can deliver. There is no

necessary one-to-one correspondence between political voluntarismand fed-

eralism or between market liberalism and intergovernmentalism. The

absence of EU-wide collective bargaining is no evidence that European inte-

gration is irrelevant to labor policy in Europe.

We should also note that the intergovernmental and federal facets of polit-

ical voluntarism are not empirically incompatible. A regional system of

interest representation, if any, would have to be built in a first stage on the

shoulders of the existing national ones. European peak associations and

European parties will be conglomerations of national units for an indefinite

amount of time.

We recapitulate the argument. Europeanization, unlike globalization,

walks on two legsmarket efficiency and political voluntarism. The market

has decentralizing and deregulating effects, making Europeanization synon-

ymous with globalization. In contrast, the polity has centralizing effects, dis-

tinguishing Europeanization from globalization.

Equipped with these definitions, we are now in a position to sort out the

relative impact of the single market and the political union while controlling

for the impact of globalization. We consider four areas of interest representa-

tionthe labor market, the capital market, and the political system, with the

latter subdivided into political parties and subnational governments. In each

case, we ask two questions: Are any of the changes that are observable in

interest representation attributable to Europeanization as opposed to global-

ization? If so, are any of these changes associated with the voluntarist compo-

nent of Europeanization as opposed to the market component? We answer

both questions in the affirmative with respect to the party system and

subnational governments only. In factor markets, we find Europeanization to

be globalization by another name.

We first present the research design followed by a quantitative survey of

the four points of impact of globalization and Europeanization. The article

ends with some general conclusions.

232 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

RESEARCH DESIGN

Our choice of method should enable us to separate three hypothetical

effects: market globalization, market Europeanization, and voluntarist

Europeanization. Either of the last two effects, moreover, may either be trig-

gered by globalization or be sui generis.

2

This makes for five hypothetical

situations:

1. The first, termed globalization-plus, implies that Europeanization is a

regional case of market broadening and deepeninga regional instance of

globalization. According to this hypothesis, EU-member countries are subject

to two cumulative forms of market broadeningglobal and regional. As a

result, European countries should evince a stronger case of globalization than

non-European countries. The globalization-plus effect implies that

Europeanization is driven by the market.

2. The opposite state, dubbed globalization-minus for reasons soon to be appar-

ent, implies that Europeanization is an insurance against external market

vicissitudes. According to this hypothesis, European countries are subject to

two opposite demandsglobalization and antiglobalizationwhich force

them to choose a lower level of globalization than non-European countries.

Cases of globalization-minus directly reveal the impact of the voluntarist

component of Europeanization.

3. The sui generis market effect implies that Europeanization has effects that are

unique to EU countries (that is, an effect associated with Europe that is not

caused by globalization). Two cases are possible depending on whether this

sui generis effect is generated by the market or by voluntarist policies.

4. The sui generis voluntarist effect is the second case of sui generis effects.

5. Last, the null effect corresponds to the situation in which Europeanization has

no discernible impact one way or another. According to the null hypothesis,

European countries should exhibit the same level of globalization as

non-European countries.

We will test for the first, second, third, and fourth hypotheses combined

and the fifth by means of one multiple regression equation. We will then sep-

arate the third and fourth hypotheses by resorting to two different specifica-

tions of the Europeanization variable.

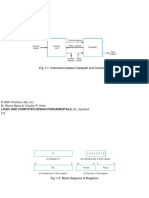

Our generic equation examines the impact of globalization and

Europeanization together and interactively.

Y

t

=

1

+

2

(Y

t 1

) +

3

(Glob

t

) +

4

(Euro

t

)

+

5

(Glob

t

*Euro

t

) +

6

(X

t

) +

t

.

(1)

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 233

2. We assume that globalization is exogenous to Europeanization.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Our dependent variable is one of the four areas of interest representation

(Y

t

) already referred tolabor, finance, elections, and local governments.

Our model specification says that the domestic dimension at time t can

depend on its prior value (Y

t 1

), globalization (Glob

t

), Europeanization

(Euro

t

), the interaction of globalization and Europeanization (Glob

t

*Euro

t

),

and a set of control variables (X

t

) to be specified in each case.

The coefficients

3

,

4

, and

5

play the central role in tests of our hypothe-

ses. The presence of the interaction termbetween Europeanization and glob-

alization means that we can interpret

3

as the effect of globalization where

Europeanization is absent (see Friedrich, 1982). This is most easily seen

where Europeanization (Euro

t

) is simply captured by a dummy variable dis-

tinguishing the EUcountries (coded 1) fromthe other countries (coded 0). In

the case in which Euro

t

is equal to zerothat is, for the non-EU coun-

triesEquation 1 reduces to:

Y

t

=

1

+

2

(Y

t 1

) +

3

(Glob

t

) +

6

(X

t

) +

t

.

(2)

In Equation 2, the coefficients

4

and

5

do not appear because non-EU

countries have a zero score on the variable to which these coefficients apply.

3

is the effect of globalization in non-EU countries. In the case in which

Euro

t

is equal to1that is, for EUcountriesthe corresponding equation is

Y

t

=

1

+

4

+

2

(Y

t 1

) + (

3

+

5

)(Glob

t

) +

6

(X

t

) +

t

.

(3)

In this case, the coefficient for the EUdummy variable (

4

) can be thought

of as an extra term added to the intercept of the regression model, and the

effect of globalization on EU members is given by the sum

3

+

5

. In sum,

estimating Equation 1 yields the impact of globalization on EU countries

(

3

+

5

) and non-EU countries (

3

).

The globalization-plus hypothesis implies that the effect of globalization

in the EUcountriesnamely, the sum

3

+

5

has the same sign as its effect

on non-EU countries

3

and is significantly larger than it (significantly

and significant are used throughout to mean statistically different from zero

at the 5%level).

3

In this case, globalization is operating in the same direction

within and outside the EU, but its effect is stronger within the EU. A special

case occurs when

3

is not significant but

3

+

5

is. In this case, globalization

would be having an effect within the EU but not outside it. European mem-

234 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

3. The standard error of

3

+

5

is given by the square root of the sum of the variance of

3

plus the variance of

5

plus twice the covariance between these two parameters. These quantities

can all be obtained fromthe variance-covariance matrix of the parameter estimates. Note that

3

and

3

+

5

are significantly different if

5

is significantly different from zero because

5

is the

difference between

3

and

3

+

5

.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

bership would thus be revealing the otherwise latent effect of globalization.

Although it is a subcategory of the globalization-plus hypothesis, we will

refer to this case as one of revealed globalization.

4

The globalization-minus hypothesis implies (a) that

3

+

5

has the same

sign as

3

and that

3

+

5

is significantly closer to zero than

3

or (b) that

3

and

3

+

5

have different signs and are significantly different. In the first

case, the overall effect of globalization is weaker in the EUthan outside it; in

the second, the effect runs in different directions in each.

5

If

3

is statistically significant but

5

is not, then the impact of globaliza-

tion is the same within the EUas in the rest of the OECD. In this case, neither

the globalization-plus nor the globalization-minus hypotheses would be

supported.

Our third hypothesisthe sui generis European effectis tested using

the

4

coefficient. If this is statistically significant, it means that there is a dif-

ference between the EU and the other countries in our sample that does not

arise as a result of the differential effects of globalization (because these are

captured in

3

and

5

). Specifically, the change in the dependent variable

would, on average, be either larger (

4

positive and significant) or smaller (

4

negative and significant) in the EU than outside it. Note, however, that if

4

were significant and the conditions for the globalization-plus hypothesis,

given above, were met, this would be a case in which there were two sorts of

Europeanization taking placecatalyzed by globalization and sui generis.

Similarly, we could also find a globalization-minus effect operating together

with the sui generis effect.

Finally, our fourth hypothesisthe null effectwould be supported if in

Equation 1, given

3

is significant, neither

4

nor

5

was significant. In such a

case, the impact of globalization would not be distinctive in Europe and there

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 235

4. The revealed-globalization effect is not to be confused with a sui generis effect of

Europeanization soon to be presented because the latter does not require the presence of global-

ization in order to occur.

5. A (fictitious) example may help visualize the difference between the two cases. Were

greater trade openness to have the overall effect of decentralizing wage bargaining between

employers and unions fromthe national to the plant level, European governments could weaken

that impact by raising trade barriers. In such a case, globalization would decentralize wage bar-

gaining outside the EU(

3

is negative and significant) and would have a different impact among

EU countries (

5

is positive and significant), that is, no impact whatsoever (

3

+

5

not signifi-

cantly different from zero). Alternatively, European employers could respond to the trade chal-

lenge by increasing coordination with the unions at the central level, as in a planned economy. In

this second case, globalization would still decentralize wage bargaining among non-EU coun-

tries (

3

is negative and significant) and would still have a different effect in EUcountries (

5

is

positive and significant), that is, to centralize wage bargaining (

3

+

5

is positive and

significant).

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

would not be any sui generis European effect. Asubcategory of the null effect

is no effect anywhere, inside and outside the EU.

The same strategy applies in those cases in which Europeanization is mea-

sured as a continuous rather than as a dummy variable. The only minor com-

plication is that the effect of globalization will be given by

3

+

5

*Euro

t

for all countries and, because the coefficient for globalization is then a

function not only of parameters but also of the value of the Europeanization

variable, its statistical significance will likewise depend on the value of

Europeanization.

In summary, four of our five hypotheses are tested by focusing on the

coefficients of Equation 1. It remains to explain how we differentiate be-

tween Hypotheses 3 (sui generis market effect) and 4 (sui generis volun-

tarist effect). We need two distinct measures of Europeanization, differ-

ing in terms of their relative sensitivity to each effect. The simplest measure

of Europeanizationa dummy variable taking a value of 1 for countries that

are part of the EUand 0 for countries that are notis a reasonable measure of

the voluntarist component of European integration. But it is not a good mea-

sure of the market component, for it presumes that all member countries have

the same exposure to European market forces when in fact they do notthe

large countries are much less exposed than the small ones. Conversely, a

measure of the trade dependence of a country on the EU countries is a good

measure of the market component of European integration but a poor mea-

sure of the voluntarist component of that same integration. It ranks Switzer-

land, which is not a member of the EUalthough almost totally dependent on it

for its trade, above Germany, which although one of the original members of

the EU, is a large country whose economy is comparatively less exposed to

external market forces in general. Hence, we will choose between Hypothe-

ses 3 and 4 according to whether the sui generis effect is stronger with the

European transaction dependence variable or with the EU dummy.

We will pattern the European transaction dependence variable after the

globalization variables. A commonly used measure of globalization is trade

dependence, calculated as the sumof a countrys imports and exports divided

by that countrys gross domestic product. The equivalent measure of the mar-

ket component of Europeanization can be calculated as the sum of a coun-

trys imports and exports with members of the common market divided by

that countrys gross domestic product. Another common measure of global-

ization is dependence on capital flows. Several variations of it are conceiv-

able. Quinn (1997) built a yearly index of legal openness that summarizes

each countrys exchange restrictions during the 1950-1993 period. One may

also use differentials in interest-covered parity (Shepherd, 1994) on the

grounds that the absence of flows does not constitute a priori evidence of

236 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

market segmentation. Or more simply, one may use the International Mone-

tary Fund and OECD measures of actual capital flowsdirect, portfolio,

loans, or total. However, there is a problem with all these measures, for they

do not allow for the calculation of an equivalent Europeanization index, the

first two because a countrys exchange controls and interest rates are undif-

ferentiated by countries of destination, the last one (actual flows) because of

data limitations. Country-by-country breakdowns of capital flows exist for

direct investment only, and flowdata are not available before the mid-1970s.

Because it takes about 10 years of flowdata to calculate a reasonably accurate

measure of stock, stock data are not available before the mid-1980s or even

later for many countries.

6

The models are tested on the population of OECDcountries. The OECDis

a club of rich countries, and this makes for a homogeneous sample of cases.

The fact that all EU countries are OECD members but not all OECD coun-

tries are EU members provides us with the requisite control group, without

which it would be impossible to distinguish between the effects of the two

external mechanisms. Moreover, the fact that not all European countries are

EU members is also important in separating the effects of EU membership

from the effects that derive from a common political history and geographic

proximity. All findings reported below are robust to the inclusion of a Euro-

pean geopolitical dummy, coded 1 for the countries located in the geographic

region of Europe and 0 for others.

The dependent variables are several dimensions of domestic societies that

are affected by globalization and/or Europeanization. We cover the two fac-

tor markets (labor and finance) and, within the political arena, national par-

ties and local governments.

The estimation method varies with the type of data and their availability.

In the presence of time-series cross-sectional dataour standardwe use

generalized least squares with panel-corrected standard errors (see Beck &

Katz, 1996). We include dummy variables for each country but one to elimi-

nate idiosyncratic differences in scale between countries (fixed effects).

Our standard specification is Equation 1, including the lagged dependent

variable. We will refer to it as the lagged dependent variable model. We will

use it as default, except in three cases.

First, if the coefficient on the lagged dependent variable exceeds 0.9, we

test for cointegration. A coefficient close to one indicates that the dependent

variable has a long memory or is path dependent. We then look for variables

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 237

6. Flow (unlike stock) data are also notoriously volatile, making their use hazardous other

than in the form of 10-year averages. Data were extracted from the annual issues of OECDs

International Direct Investment Statistics Yearbook and National Accounts over a 30-year

period.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

that maintain a predictable relationship (are cointegrated) with the depend-

ent variable in the long run and are weakly exogenous to it. The cointegra-

tion model we use is identical to the one suggested by Beck and Katz (1996,

p. 11):

Y

i, t

=

1

+

3

Glob

i, t

+

4

Euro

i, t

+

5

[Glob

i, t

*Euro

i, t

]

+

6

X

i, t

+

2

(Y

t 1

3

Glob

i, t 1

4

Euro

i, t 1

5

[Glob

i, t 1

*Euro

i, t 1

]

6

X

i,t 1

) +

i, t

,

(4)

with, on the right-hand side, coefficients for the change variables measuring

short-termeffects (

3

,

4

,

5

, and

6

) and coefficients for the lagged variables

measuring long-termeffects (the

2

s). Cointegration between the dependent

variable and an independent variable is verified when both

2

and the product

between

2

and the coefficient for the lagged independent variable are sig-

nificant. If Euro is a dummy variable, Equation 4, like Equation 1, reduces to

two simpler equations, with

2

3

measuring the long-term impact of global-

ization on non-EUcountries,

2

(

3

+

5

) measuring that on EUcountries,

2

5

measuring the long-term difference in the way globalization affects EU and

non-EU countries, and

2

4

measuring the sui generis effect.

Second, if the coefficient does not exceed 0.9, we use the specification

given by Equation 1. But following Beck and Katz (1996), we test this model

against the more general model in which it is nested. We refer to this as the

all-lagged model:

Y

i, t

=

1

+

2

Y

t 1

+

3

Glob

i, t

+

4

Euro

i, t

+

5

[Glob

i, t

*Euro

i, t

]

+

6

X

i, t

+

3

Glob

i, t 1

+

4

Euro

i, t 1

+

5

[Glob

i, t 1

*Euro

i, t 1

]

+

6

X

i, t 1

+

i, t

.

(5)

Finally, if pooling time and cross-sectional series is impractical, we

regress the change in domestic dimension against its value at the beginning of

the period and corresponding changes in the other right-hand-side variables.

We will refer to this specification as the cross-sectional change model.

7

Although quite intelligible, this method presents two drawbacks. First, it

misses nonlinear changes (that is, changes between the initial and terminal

value of the dependent variable that bounce around the trend spanning these

two values). This is a minor problem, however, in the presence of data exhib-

iting trends. A second drawback of the cross-sectional design is the small

number of observations that we can feed into it, requiring that we be watchful

for potential outliers. We want to guard against reporting as finding results

238 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

7. It is similar to Equation 1 except that all variables on both sides (except for the lagged

dependent variable) appear as first differences, and t-1 refers to the starting value of a multiyear

period and t to its terminal value.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

that are driven by outlying values and against discarding correlations that are

hidden by outliers.

ORGANIZATION OF THE LABOR MARKET

There exists a consensus in the labor literature that globalization of mar-

kets is forcing employer-employee relations to become less corporatist and

more fragmented. The internationalization of capital is rendering national

labor confederations irrelevant because these national organizations are

unable to coordinate across national boundaries and together establish an

international labor confederation. As a result, wage bargaining is decentral-

ized to lower levels, rates of unionization are dropping, strike activity is

declining, and government employment is shrinking. On the rise are unem-

ployment, part-time employment, and performance-related pay (see Crouch,

1993; Ferner &Hyman, 1992; Streeck, 1987). Is this trend equally felt among

EU countries?

Two hypotheses are plausible a priori. On one hand, European labor mar-

kets are not immune to market shocks but, in fact, are even more affected by

themin light of the more advanced level of product and financial market inte-

gration achieved in Europe. On the other hand, prospects for coordination

among national labor confederations are brighter inside than outside the EU.

The existence of intergovernmental institutions, along with the prodding of

the commission and the court, makes it at least conceivable that enough regu-

latory coordination could be achieved to offset the worst effects of capital

internationalization. The social pillar of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, how-

ever fledgling it may look, signals a different choice for Europe. In sum, EU

membership may offer trade unions and their governments additional politi-

cal options besides market adjustment, justifying the preservation of social

corporatism at the national level.

We test these two hypotheses against each other and the null hypothesis on

two labor market dimensions: trade union density and wage-bargaining

level. Our findings offer support for the market integration hypothesis. We

find that Europeanization has no bearing on trade union density. With respect

to bargaining level, we find that financial openness has a globalization-plus

effect in which the EU significantly outperforms the rest of the OECD.

We start with union density. We control for the presence of left parties

in government. Because the literature is unanimous about the idea that left

government is positively correlated with corporatism, the test gains in accu-

racy if that effect is held constant. We also control for the four cases in

which the payment of unemployment benefits is administered by the unions

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 239

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. In these countries, unemployment

increases the incentives for workers to join a union. We finally control for

geographic presence in Europe.

8

We use two alternative measures of globalization: nominal capital open-

ness and trade dependence. Data availability allows us to pool data for 16

countries during 30-plus years of observations. The coefficient of the lagged

dependent variable is very close to one, requiring the use of the cointegration

method presented in Equation 4.

Two series of results are worth reporting (see Table 1). First, two of the

control variables confirm existing claims. Left government is positively

related with trade union density in the long run; it tests significant in the

financial globalization regression (Equation 1), and marginally so (at the

5.6% level) in the trade dependence regression (Equation 2). Long-run

upward shifts to the left of the ideological spectrum generate long-run

upward growth in trade union density. Also, countries in which unemploy-

ment benefits are distributed by the unions show a long-term level of union-

ization higher than average. The European geopolitical dummy fails to test

significant, however, suggesting that there is nothing particular about Euro-

pean geography or history with respect to trade union membership.

Second, we find three types of effects of Europeanizationa globalization-

plus effect adding to the demobilizing effect of globalization, a sui generis ef-

fect pointing to mobilization, and a null effect. The first two effects are found

in Regression 1 (the financial globalization regression). The globalization-

plus effect can be read fromthe coefficients

2

3

,

2

5

,

2

(

3

+

5

); they are all

negative and significant. Nominal capital openness has a significantly

greater negative long-term impact on trade union membership in EU than in

non-EU countries. This globalization-plus effect is supplemented with an

equally long-termsui generis effect.

9

That effect works in the opposite direc-

tion of globalization (

2

4

is positive and significant), canceling the latter at

low values of globalization but being canceled at higher values. The tipping

point, before which the sui generis effect prevails and past which the global-

ization-plus effect predominates, is equal to 8.11.

10

Every EU member had

already passed that threshold by the time it joined the common market, sug-

240 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

8. Our fixed-effects specification also controls for all factors that are country specific and

time invariant.

9. The sui generis effect disappears if one substitutes the variable European trade depend-

ence for the EU membership dummy, suggesting a political rather than a market origin.

10. The calculation of the tipping point runs as follows. The two effects on EUcountries add

up to

2

4

+

2

(

3

+

5

)*Glob

i, t 1

. When the net effect is equal to 0, Glob

i, t 1

is equal to

2

4

/

2

(

3

+

5

)that is, 8.11 in Regression 1.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 241

Table 1

Trade Union Density (cointegration model with fixed effects, generalized least squares esti-

mates, and panel-corrected standard errors)

Dependent Variable:

Trade Union Density

1 2

Trade union density

i, t 1

2

0.02 (2.51)

a

0.02 (2.50)

a

Nominal financial openness

i, t

3

0.12 (1.18)

Trade dependence

i, t

3

0.79 (0.98)

EU membership

i, t

4

0.17 (0.25) 4.98 (1.49)

Nominal financial openness

i, t

*EU membership

i, t

5

0.37 (0.48)

Trade dependence

i, t

*EU membership

i, t

5

30.02 (1.49)

Left party cabinet portfolio

i, t

0.004 (1.42) 0.003 (0.93)

Nominal financial openness

i, t 1

2

3

0.10 (2.45)

a

Trade dependence

i, t 1

2

3

0.81 (2.03)

a

EU membership

i, t 1

2

4

2.19 (2.31)

a

0.33 (0.73)

Nominal financial openness

i, t 1

*EU membership

i, t 1

2

5

0.17 (2.08)

a

Trade dependence

i, t 1

*EU membership

i, t 1

2

5

0.52 (0.89)

Left party cabinet portfolio

i, t 1

0.004 (2.10)

a

0.003 (1.90)

Unemployment benefits paid by

unions (dummy for Belgium,

Denmark, Finland, and Sweden)

i

1.13 (1.67) 2.46 (3.41)

b

Geopolitical Europe

i

(dummy) 0.35 (1.39) 0.77 (0.66)

Intercept 1.39 (2.41)

a

1.52 (1.85)

3

+

5

0.12 (1.18) 0.79 (0.98)

2

(

3

+

5

) 0.27 (3.76)

b

1.32 (2.94)

b

Number of observations 592 512

Number of groups 16

c

16

c

Number of time periods 37

d

32

e

Log likelihood 685.7757 535.6337

Probability (chi-square) 0.0000 0.0000

Note: EU=European Union. The dependent variable is the first difference in trade union density

adjusted for missing data by Golden, Lange, and Wallerstein (1997). Nominal financial open-

ness is the level of nominal financial openness coded on a 0 to 12 scale by Quinn and Toyoda

(1997). Left power is the percentage of all cabinet portfolios held by left parties; the source is

Swank (1998). Trade dependence is the ratio (imports + exports)/gross domestic product; the

source is OECD (National Accounts; see note 6). EU membership is a dummy variable coded 1

for member countries at year t, 0 for all others. Geopolitical Europe is a dummy coded 1 for the

countries located in the geographic region of Europe and 0 for others. All the multiplicative

variables are the product of their unstandardized components. Values of z statis-

(continued)

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

gesting that the net effect of EUmembership on trade union membership was

always negative.

The impact of trade dependence on trade union membership is also gener-

ally negative. Regression 2 suggests that trade dependence is cointegrated

with the decline in trade union density within and outside the EU (

2

3

and

2

[

3

+

5

] are negative and significant). However, there is no difference

between EUand non-EUmembers (

2

5

is not significant). The findings con-

formwith the null hypothesis, according to which Europeanization makes no

difference one way or another.

We now turn to the bargaining level (see Table 2). The coefficient on the

lagged dependent variable (

2

) is well below 0.90, allowing us to bypass the

cumbersome cointegration technique. Moreover, tests for residual serial cor-

relation suggest that the lagged dependent variable takes out most of the

serial correlation fromthe data.

11

We also estimated both the full all-lagged

model (Equation 5), in which the lagged values for both the dependent and

the independent variables are included on the right-hand side of the regres-

sion, and the simpler model (Equation 1), including only the lagged depend-

ent variable. We then performed a likelihood-ratio test. The hypothesis that

the two equations are identical could not be rejected at the 5% confidence

level. These results allow us to use the simple lagged-dependent-variable

model of Equation 1. The left government variable tests positive and signifi-

cant in Regression 1 and marginally significant in Regression 2. The dummy

for European geography and history tests positive and highly significant in

the second regression.

The story about financial globalization is much the same as for trade union

density. Although its impact on non-EU countries (

3

) is indeterminate, that

on EUmembers is significantly different (

5

) and negative (

3

+

5

)a typi-

cal revealed-globalization effect, that is, a subcategory of globalization-plus.

242 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

Table 1 Continued

tics are given in parentheses. All Greek symbols refer to Equation 4 in the text. The unit of obser-

vation is the country year.

a. z is significant at the 5% level.

b. z is significant at the 1% level.

c. Australia, Austria, Belgium-Luxembourg, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,

Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the

United States.

d. 1955 to 1992.

e. 1960 to 1992.

11. We regressed the residuals against their lagged value and found no significant

correlation.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Simultaneously, the EU dummy exhibits a positive sui generis effect (

4

),

prevailing over the former effect for values of globalization inferior or equal

to 8.33a threshold barely higher than the one we calculated for trade union

density (see Regression 1, Table 1). Once again, because all EUmembers had

more or less passed that threshold by the time they joined the common mar-

ket, the net effect of EUmembership on trade union membership was always

negative.

The effect of trade dependence on bargaining level in Regression 2 is

unclear, hesitating between a weak case of globalization-minus and the null

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 243

Table 2

Bargaining Level (lagged-dependent variable model with fixed effects, generalized least

squares estimates, and panel-corrected standard errors)

Dependent Variable:

Level of Wage Bargaining

1 2

Bargaining level

i, t 1

2

0.56 (16.94)

b

0.56 (15.58)

b

Nominal capital openness

i, t

3

0.009 (0.60)

Trade dependence

i, t

3

0.34 (1.95)

EU membership

i, t

4

0.75 (2.22)

a

0.08 (0.39)

Nominal capital openness

i, t

*EU membership

i, t

5

0.08 (2.86)

b

Trade dependence

i, t

*EU membership

i, t

5

0.54 (2.05)

a

Left party cabinet portfolio

i, t

0.001 (2.06)

a

0.001 (1.86)

Geopolitical Europe

i

(dummy) 0.15 (1.78) 1.23 (3.92)

b

Intercept 1.49 (8.45)

b

0.13 (0.36)

3

+

5

0.09 (3.57)

b

0.20 (0.97)

Number of observations 608 528

Number of groups 16

c

16

c

Number of time periods 38

d

33

e

Log likelihood 132.2239 138.5172

Probability (chi-square) 0.0000 0.0000

Note: EU=European Union. The dependent variable is the level of wage bargaining coded on a 1

to 4 scale by Golden, Lange, and Wallerstein (1997); the higher the number, the more centralized

the bargaining. Values of z statistics are given in parentheses. All Greek symbols refer to Equa-

tion 1 in the text. The unit of observation is the country year.

a. z is significant at the 5% level.

b. z is significant at the 1% level.

c. Australia, Austria, Belgium-Luxembourg, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,

Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the

United States.

d. 1955 to 1992.

e. 1960 to 1992.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

effect. Trade dependence has a marginally negative effect on non-EU coun-

tries (

3

is positive but not significant at the 5%level); it affects EUmembers

differently (

5

is positive and significant)that is, not at all (

3

+

5

is not dif-

ferent from zero). Most of the action is stolen by the geopolitical dummy, of

which the positive coefficient suggests that bargaining levels in Europe are

generally higher than elsewhere when controlling for trade dependence.

Taking all results into consideration, trade does not seemto cause much of

a difference between EU members and nonmembers. Financial openness, in

contrast, exhibits a prevailing globalization-plus effect on trade union den-

sity and wage bargaining. In sum, our analysis lends plausibility to the

detractors of European social policy and the claim that European integration

is essentially market driven. Corporatism in the labor market, along with the

possibility of market-correcting intervention, is declining fast among EU

countries, faster than elsewhere. We found no evidence that labor confedera-

tions in the EU are any more capable of coordination across national bound-

aries within the EU ambit than outside it. Employees desert national labor

unions everywhere, indeed more so within than outside the EU. European

integration does not offer trade unions and their government political options

justifying the preservation of social corporatism at the national level.

ORGANIZATION OF THE CAPITAL MARKET

Recent research has shown that capital markets, like labor markets, can be

more or less corporatist (Deeg, 1998; Verdier, 2000b). A corporatist capital

market is one in which the interests of various borrowers (savers are never

organized) are organized and articulated by various centralized institutions.

Two types of borrowers compete for cash in capital marketssmall- and

medium-sized enterprises, which do not enjoy sufficient visibility to be

traded on the market, and large enterprises, which do possess that visibility.

These groups are not directly organized into confederations, but their respec-

tive bankers are. The bankers for large firms are the large center banks, head-

quartered in the national financial center and engaged in fierce competition

with each other. The bankers for the small- and medium-sized companies, in

contrast, are typically sheltered from the competition of the large banks.

Their identities vary according to country: In Germany, Austria, Italy, Swit-

zerland, and the Scandinavian countries especially, small firms bank with the

nonprofit sector, which is composed of the savings banks, cooperative societ-

ies, and local banks controlled by local governments. In the United States, the

only country that still allows local governments to charter for-profit banks,

small firms also bank with locally chartered for-profit country banks. In

244 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

France, Belgium, New Zealand, and the Netherlands, the small borrowers

main banker is (or was) the state credit sector, which includes all the special-

ized credit facilities that enjoy state borrowing privileges.

12

The relative mar-

ket share of each sector varies greatly across countries: In 1990, the competi-

tive sector represented 92%of all banking assets in Australia but only 27 %in

Germany; the state sector captured 25% of French banking assets but was

nonexistent in Ireland, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Each banking sector in each country is organized in a national trade asso-

ciation, whose role is to ensure that the rules of coexistence between sectors

laid down by the central government agencies are not disadvantageous to its

own sector. Unsurprisingly, these sectors hold conflicting regulatory prefer-

ences: The large banks favor market mechanisms, whereas nonprofit, local,

and state banks favor, indeed need, regulatory protection from the center

banks.

Capital markets have been greatly affected by financial globalization. Dereg-

ulation has caused an increase in competition, forcing banks to concentrate

and shift away fromlending toward market activities.

13

The Basle agreement

on capital-assets ratios, one of the fewinstances of voluntarismin the domain

of financial globalization, forced banks throughout the world to strengthen

their solvability. Although the impact of financial globalization is much dis-

cussed, that of Europeanization seems nonexistent. Banking and financial

regulation has received a lot of attention from the council and the commis-

sion, especially in the early 1980s.

14

Yet, of the few studies that have looked

for a European specificity, none has found any. Firms and banks offer as much

diversity in Europe as outside Europe (Cerasi, Chizzolini, & Ivaldi, 1998).

We argue that the effect of Europeanization is a priori indeterminate; it

depends on which of the market or voluntarist components prevail. Integra-

tion through market deregulation is likely to favor the market-oriented,

for-profit sector. Although it may lead to greater concentration in that sector,

it would also yield a decentralization of interest representation. This is

because the interests of each class of borrower would no longer be allocated

through summit negotiations, involving government regulators along with

representatives of the various banking sectors but would be decided by com-

petition among a handful of oligopolies. Voluntarist integration, in contrast,

is likely to keep intact existing mechanisms for the regulation of credit (or

reproduce them at the supranational level in the European Ecofin commit-

tee), and thus freeze the existing allocation of market shares between sectors.

Verdier, Breen / EUROPEANIZATION AND GLOBALIZATION 245

12. On the state sector, see Verdier (2000a).

13. On concentration, see T. Porter (1993) and Cerasi (1996); on securitization, see Thomp-

son (1995).

14. See contributions by and to Underhill (1997).

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Therefore, if financial globalization favors concentration and market orienta-

tion, it should correlate with a redistribution of market shares away from the

sheltered sectors (the local nonprofit, country, and state banks) toward the

unsheltered sector (the center banks). If membership in the EU makes a dif-

ference, the impact should be significantly distinct in the case of the sin-

gle-market countries.

We ran the tests on two sectors, center and state, using respective market

shares calculated in total assets. The coefficient on the lagged dependent

variable being close to one, we use the cointegration model. We used only

two measures of globalizationnominal capital openness and trade depend-

ence because various measures of cross-border capital flows variables

yielded no results whatsoever.

15

The findings support the two sides of the null

hypothesis (see Table 3). First, long-termincreases in globalization correlate

with long-termincreases in center banks market share and long-termdecline

in state banks market share. Second, European integration makes no differ-

ence whatsoever.

Regressions 1, 2, and 3 have a common structure. The long-termimpact of

the global variable on non-EUcountries, which can be read from

2

3

, is cor-

rectly signed and significantpositive for center banks, negative for state

banks. However, the coefficient on the long-term interaction term (

2

5

) is

insignificant, suggesting an identical impact within and outside the EU.

Regression 4 also fails to show a difference between the two groups, detect-

ing no impact of globalization anywhere.

These results clearly suggest that the European capital market is an inte-

gral component of the global market. Market reform took place among EU

countries at the same speed as among non-EU countries. We found no trace

of Europeanization, let alone voluntarism, in financial markets. Furthermore,

aside from the isolated negative result of Regression 4, globalization does

have a long-term deregulatory impact on interest organization among finan-

cial institutions.

ELECTORAL TURNOUT AND VOLATILITY

As markets thus become more important in (re)distributing income, polit-

ical parties should become relatively less so. One should expect rational indi-

viduals to reallocate some of their wealth-maximizing effort away frompoli-

tics toward markets. Loyalty to political parties should decline, and the

246 COMPARATIVE POLITICAL STUDIES / April 2001

15. The extreme volatility of annual cross-border flows data considerably reduce their effi-

ciency as a measure of financial globalization. Stock data are steadier, but time series are too

short to be used in a time-series cross section.

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

T

a

b

l

e

3

B

a

n

k

i

n

g

S

e

c

t

o

r

s

M

a

r

k

e

t

S

h

a

r

e

s

(

c

o

i

n

t

e

g

r

a

t

i

o

n

m

o

d

e

l

w

i

t

h

f

i

x

e

d

e

f

f

e

c

t

s

,

g

e

n

e

r

a

l

i

z

e

d

l

e

a

s

t

s

q

u

a

r

e

s

e

s

t

i

m

a

t

e

s

,

a

n

d

p

a

n

e

l

-

c

o

r

r

e

c

t

e

d

s

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

e

r

r

o

r

s

)

D

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

t

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

C

e

n

t

e

r

B

a

n

k

s

M

a

r

k

e

t

S

h

a

r

e

i

,

t

S

t

a

t

e

B

a

n

k

s

M

a

r

k

e

t

S

h

a

r

e

i

,

t

1

2

3

4

C

e

n

t

e

r

b

a

n

k

s

m

a

r

k

e

t

s

h

a

r

e

i

,

t

0

.

0

3

(

2

.

3

0

)

a

0

.

5

9

(

3

.

6

3

)

b

S

t

a

t

e

b

a

n

k

s

m

a

r

k

e

t

s

h

a

r

e

i

,

t

0

.

0

3

(

2

.

9

1

)

b

0

.

0

4

(

2

.

8

8

)

b

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

f

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

o

p

e

n

n

e

s

s

i

,

t

3

0

.

0

0

0

4

(

0

.

2

7

)

0

.

0

0

0

3

(

0

.

2

2

)

T

r

a

d

e

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

c

e

i

,

t

3

0

.

0

2

(

1

.

7

3

)

0

.

0

0

3

(

0

.

2

6

)

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

0

.

0

2

(

1

.

2

9

)

0

.

0

2

(

0

.

8

8

)

0

.

0

1

5

(

0

.

9

8

)

0

.

0

0

7

(

0

.

5

6

)

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

f

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

o

p

e

n

n

e

s

s

i

,

t

*

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

0

.

0

0

2

(

0

.

9

1

)

0

.

0

0

1

(

0

.

8

6

)

T

r

a

d

e

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

c

e

i

,

t

*

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

5

0

.

3

3

(

1

.

9

3

)

0

.

1

1

(

0

.

8

0

)

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

f

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

o

p

e

n

n

e

s

s

i

,

t

3

0

.

0

0

2

(

3

.

4

6

)

b

0

.

0

0

0

9

(

2

.

4

8

)

a

T

r

a

d

e

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

c

e

i

,

t

3

0

.

0

2

(

3

.

4

8

)

b

0

.

0

0

6

(

1

.

5

3

)

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

4

0

.

0

0

7

(

0

.

8

7

)

0

.

0

0

6

(

1

.

2

5

)

0

.

0

1

(

1

.

9

5

)

0

.

0

0

1

(

0

.

3

9

)

N

o

m

i

n

a

l

f

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

o

p

e

n

n

e

s

s

i

,

t

1

*

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

0

.

0

0

0

8

(

0

.

9

2

)

0

.

0

0

1

(

1

.

9

2

)

T

r

a

d

e

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

c

e

i

,

t

1

*

E

U

m

e

m

b

e

r

s

h

i

p

i

,

t

0

.

0

0

8

(

1

.

3

9

)

0

.

0

0

2

(

0

.

3

3

)

G

e

o

p

o

l

i

t

i

c

a

l

E

u

r

o

p

e

i

(

d

u

m

m

y

)

0

.

0

2

(

3

.

0

9

)

b

c

0

.

0

0

3

(

0

.

6

4

)

c

D

a

t

a

b

r

e

a

k

s

(

d

u

m

m

i

e

s

)

I

n

t

e

r

c

e

p

t

0

.

0

1

(

1

.

4

2

)

0

.

0

6

5

(

4

.

1

2

)

b

0

.

0

2

(

2

.

6

9

)

a

0

.

0

0

8

(

0

.

9

8

)

3

+

0

.

0

0

1

(

0

.

8

8

)

0

.

0

2

(

1

.

7

3

)

0

.

0

0

2

(

1

.

2

9

)

0

.

0

0

3

(

0

.

2

6

)

2

(

3

+

5

)

0

.

0

0

0

9

(

1

.

2

0

)

0

.

0

1

(

2

.

1

6

)

a

0

.

0

0

0

4

(

0

.

6

0

)

0

.

0

0

8

(

1

.

6

4

)

(

c

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

247

at Alexandru Ioan Cuza on December 20, 2011 cps.sagepub.com Downloaded from

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

o

b

s

e

r

v

a

t

i

o

n

s

5

3

2

4

3

7

5

3

2

4

3

7

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

g

r

o

u

p

s

1

3

d

1

3

d

1

3

d

1

3

d

A

v

e

r

a

g

e

n

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

t

i

m

e

p

e

r

i

o

d

s

4

1

e

3

3

f

4

1

e

3

3

f

L

o

g

l

i

k

e

l

i

h

o

o

d

1

7

1

9

.

6

9

8

1

4

1

9

.

5

2

7

1

8

4

3

.

2

5

7

1

5

4

1

.

9

2

8

P

r

o

b

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

(

c

h

i

-

s

q

u

a

r

e

)

0

.

0

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

0

0

.

0

0

0

0

N

o

t

e

:

E

U

=

E

u

r

o

p

e

a

n

U

n

i

o

n

.

T

h

e

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

t

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

a

r

e

t

h

e

f

i

r

s

t

d

i

f

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

o

f

t

h

e

r

e

s

p

e

c

t

i

v

e

m

a

r

k

e

t

s

h

a

r

e

s

o

f

c

e

n

t

e

r

a

n

d

s

t

a

t

e

b

a

n

k

s

.

B

o

t

h

t

y

p

o

l

o

g

y

a

n

d

d

a

t

a

a

r

e

f

r

o

m

V

e

r

d

i

e

r

(

2

0

0

0

a

)

.

V

a

l

u

e

s

o

f

z

s

t

a

t

i

s

t

i

c

s

a

r

e

g

i

v

e

n

i

n

p

a

r

e

n

t

h

e

s

e

s

.

A

l

l

G

r

e

e

k

s