Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Does Your Dog Understand You

Uploaded by

Nicholay Atanassov0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

58 views2 pages71% of American men believe their dogs understand them at some telepathic level. Research suggests psychological similarities beteen human and dog that might surprise even a comedian. Dogs outperform chimpanzees on several tests that re-uire understanding someone else's point of vie.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document71% of American men believe their dogs understand them at some telepathic level. Research suggests psychological similarities beteen human and dog that might surprise even a comedian. Dogs outperform chimpanzees on several tests that re-uire understanding someone else's point of vie.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

58 views2 pagesDoes Your Dog Understand You

Uploaded by

Nicholay Atanassov71% of American men believe their dogs understand them at some telepathic level. Research suggests psychological similarities beteen human and dog that might surprise even a comedian. Dogs outperform chimpanzees on several tests that re-uire understanding someone else's point of vie.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Does Your Dog Understand You?

Strong selective pressure has made Fido seem smarter

By Clive Wynne

According to Men's Health magazine, 71% of American men believe their dogs understand them at

some telepathic level.

1

The Tonight Show's host, Jay Leno, suggested that this as because men and dogs

share the same basic interests !"eat, sleep, play ball, and hump"#. $ecent research suggests psychological

similarities beteen human and dog that might surprise even a comedian.

%or years researchers have been loo&ing to chimpanzees to find glimpses of human'li&e intelligence.

(he argument, reasonable enough on its face, as that genetic relatedness ould predict psychological

similarity. )ut hat about %ido*

+hen stac&ed up against man's closest relatives, man's best friends perform remar&ably ell in tas&s

that gauge a comprehension of human commands and cues. A &nac& for vocabulary and an intense

attentiveness to human action are the &inds of behaviors that loo& intelligent to people. )ut this is because

they ere selected, first naturally and later artificially, to be adapted to their niche, human society. %urther

studies ill shed more light on ho dogs fa&e human intelligence.

DOGS GE !E "O#$ ,ogs outperform chimpanzees on several tests that re-uire understanding

someone else's point of vie . hat psychologists call "theory of mind" abilities. /ere is a simple and

compelling test that any dog oner can easily reproduce. /ide a piece of food in one of to opa-ue

containers. (he dog is not permitted to see here the food has been hidden but instead must find the food by

folloing a communicative gesture, such as pointing, by the e0perimenter.

)rian /are and colleagues at the 1a0 2lanc& 3nstitute for 4volutionary Anthropology in Leipzig,

5ermany, found that dogs, even puppies brought up at a &ennel ith minimal human contact, ere fully

competent at this tas&. 6n the other hand, of nine chimpanzees tested, only to shoed any success.

+olves performed above chance, but not as ell as the dogs.

7

8i&toria 9zetei and colleagues at 4:tv:s Lor;nd <niversity and the /ungarian Academy of 9ciences in

)udapest, found that dogs ill follo human gestures even over the evidence of their on senses. Although

the researchers used strong'smelling /ungarian salami, the dogs still ent to an empty container if the

e0perimenter pointed to it.

=

,ogs also appear to understand hat people are thin&ing far more effectively than do chimpanzees.

,aniel 2ovinelli and colleagues at the >e 3beria research center in Louisiana gave chimpanzees the choice

beteen begging for food from somebody ho could see them, and someone ho could not. 9urprisingly,

chimps shoed little understanding that there as no point in begging for food from somebody ith a buc&et

over her head.

?

@sAfia 8ir;nyi and colleagues replicated this simple test on some )udapest dogs. (he dogs

ere confronted by to unfamiliar omen, each holding a liver sandich. 6ne person faced the dog hile the

other loo&ed aay. <nli&e the chimpanzees in Louisiana, )udapest dogs spontaneously begged from only the

person ho as loo&ing at them.

B

,ogs can also use their on gazes to direct a person's attention. Cd;m 1i&lAsi and colleagues in

)udapest hid a dog's favored toy or piece of food in one of three locations in the absence of the dog's oner.

+hen the oners returned, 1i&lAsi found that the restrained dogs literally shoed their oners here the

desired obDect had been hidden, by first bar&ing to get their attention and then loo&ing bac& and forth

beteen the obDect's location and the oners.

E

3n every case the oner as able to locate the food or toy

based solely on the dog's communicative glances.

%&' O (E) *#CO 1ost dog oners notice that their pets understand at least a fe ords. ,arin's

neighbor at ,on, 9ir John Lubboc& !a ban&er and &een contributor to several branches of science#, as one

of the first to test ho much human language dogs understand. Lubboc& placed cards ith different ords on

them in front of his poodle, 8an. +hatever 8an selected he received. Lubboc& as greatly impressed by the

fre-uency ith hich 8an brought the card ith the ord "food" ritten on it.

7

(here is, hoever, no need to suppose 8an as communicating his thoughts to Lubboc&. 3t is far more

parsimonious to assume that the dog's actions ere a product of the la of effectF )ehaviors that produce

desired conse-uences ill be repeated.

A far more compelling study of language comprehension in dogs appeared this past summer. Juliane

Gamins&i and colleagues in Leipzig found a border collie, $ico, ho &ne the names of over 7HH obDects. $ico

could be ordered into a room to collect a named item from among nine other items ith hich he as also

familiar. $ico must have been responding based Dust on the name of the item, because oner and

e0perimenter remained in one room hile the dog ent into the other to ma&e his selection.

I

1ore

remar&able than Dust his vocabulary as $ico's ability to learn ne ords through a process &non as fast

mapping. (he e0perimenters used a ord that as not familiar to $ico and sent him into a room that

contained eight items. 9even of these obDects ere familiar but he did not &no the name of the eighth. 3n

seven out of ten tests ith novel ords $ico appropriately retrieved a different novel item each time. As

Gamins&i and colleagues conclude, "Apparently he as able to lin& the novel ord to the novel item based on

e0clusion learning."

Austrian philosopher Ludig +ittgenstein once remar&ed, "/oever elo-uently Jyour dogK may bar&,

he cannot tell you that his parents ere honest though poor."

L

9o, e should be careful to &eep $ico's

achievements in perspective. %or one thing, $ico forgot half of his nely learned ords ithin four ee&s.

Also, e should be ary of concluding that because dogs can respond to ords as commands to fetch obDects

that they have any understanding of grammar or synta0. >o one yet has presented evidence that a dog can

distinguish the difference beteen "man bites dog" and "dog bites man."

!E %#& (%Y W%G (he effort to find aspects of human intelligence in chimpanzees as motivated

by the recognition that chimps and people are closely related. An estimated five million years of evolution

separates people and our closest great'ape relatives. )ut for all that genetic pro0imity, chimps have spent

rather little time interacting ith us. ,ogs may not be &in, but they have been &ith for more than 1H,HHH

years. A burial site in 3srael from 17,HHH years ago contains the bodies of an old oman ith her puppy.

1H

,>A evidence suggests the association may go bac& as far as 1HH,HHH years.

11

+hatever date is finally agreed upon for the start of dog'human association, it is clear that human

society has been the dog niche for a very long time. %iguring out hat these odd, hairless apes ere up to

has been a maDor selection pressure on domestic dogsF %irst through natural selection, dogs that scrounged

around human camps had more offspring than those that fended for themselvesM later through artificial

selection, people selectively bred the traits they anted to see in companion animals. 9uch an evolutionary

account of dog smarts gains support from evidence that olves do not share dogs' successes in

communicating ith people.

3n 9eden, Genth 9vartberg and )D:rn %or&man tested more than 1B,HHH dogs from 1E? different

breeds to uncover the species' fundamental personality traits. %ive basic dimensions of canine character

emerged. %our of these five are similar to ell'established dimensions of human personalityF playfulness,

curiosity, sociability, and aggressiveness.

17

6nly chase proneness seems outside the human realm of

e0perience. Jay Leno might be surprised at ho close to the mar& he asF ,ogs really do have a lot in

common ith people. %inding the limits of that similarity promises to be a rich research seam for some time

to come.

Clive Wynne) is an associate pro+essor in psychology at the University o+ Florida) and studies animal

,ehavior in species ranging +rom pigeons to marsupials- !is latest ,oo. is Do Animals Think? pu,lished ,y

"rinceton University "ress-

*e+erences

/. 1en's /ealth 7HH=, 1I!=#F 177.

0. ) /are et al, "(he domestication of social cognition in dogs," Science 7HH7, 7LIF 1E=?'E.

1. 8 9zetei et al, "+hen dogs seem to lose their noseF an investigation on the use of visual and

olfactory cues in communicative conte0t beteen dog and oner," Appl Anim Behav Sci 7HH=, I=F 1?1'B7.

2. ,J 2ovinelli, (J 4ddy "+hat young chimpanzees &no about seeing," Monogr Soc Res

Child 1LLE, E1F i.vi'1.1B7.

3. @ 8ir;nyi et al, ",ogs respond appropriately to cues of humans' attentional focus," Behav

Proc 7HH?, EEF 1E1'77.

4. A 1i&lAsi et al, "3ntentional behaviour in dog'human communicationF an e0perimental analysis of

"shoing" behaviour in the dog," Anim Cogn 7HHH, =F 1BL'EE.

5. J Lubboc& "(eaching animals to converse," Nature 1II?, 7F B?7'I.

6. J Gamins&i et al, "+ord learning in a domestic dogF evidence for 'fast

mapping,"' Science 7HH7, =H?F 1EI7'=.

7. L +ittgenstein "(he uses of language," in The Basic Writings o Bertrand Russell !"dited #$% "gner

R"& 'enonn (")* >e Nor&F 9imon O 9chuster 1LE1, 1=1'E.

/8. 9J1 ,avis, %$ 8alla "4vidence for domestication of dog 17,HHH years ago in >atufian of

3srael," Nature 1L7I, 7E7F EHI'1H.

//. P 8ila et al, "1ultiple and ancient origins of the domestic dogs," Science 1LL7, 77EF 1EI7'L.

/0. G 9vartberg, ) %or&man "2ersonality traits in the domestic dog !Canis amiliaris#," Appl Anim

Behav Sci 7HH7, 7LF 1=='BB.

You might also like

- Exploring Psychic Abilities in PetsDocument21 pagesExploring Psychic Abilities in PetsBryan J WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Slave Contract Level 1Document2 pagesSlave Contract Level 1mg10183% (6)

- The Dog's Mind: Understanding Your Dog's BehaviorFrom EverandThe Dog's Mind: Understanding Your Dog's BehaviorRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Unwinding AnxietyDocument11 pagesUnwinding Anxietylim hwee lingNo ratings yet

- The Back of The German Shepherd DogDocument21 pagesThe Back of The German Shepherd DogNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Breed Differences in BehaviorDocument20 pagesBreed Differences in BehaviorNicholay Atanassov100% (1)

- How Dogs LearnDocument5 pagesHow Dogs LearnNicholay Atanassov100% (2)

- Animal Consciousness: Evolution and Our EnvironmentDocument11 pagesAnimal Consciousness: Evolution and Our EnvironmentmelitalazNo ratings yet

- Pallasmaa - Identity, Intimacy And...Document17 pagesPallasmaa - Identity, Intimacy And...ppugginaNo ratings yet

- If You Tame Me: Understanding Our Connection With AnimalsFrom EverandIf You Tame Me: Understanding Our Connection With AnimalsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Hospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesDocument4 pagesHospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesNesyraAngelaMedalladaVenesa100% (1)

- Overview of Language Teaching MethodologyDocument19 pagesOverview of Language Teaching Methodologyapi-316763559No ratings yet

- Animals and Language Learning Psycho Linguistics)Document23 pagesAnimals and Language Learning Psycho Linguistics)Andy Aminsyah67% (3)

- Minding Dogs: Humans, Canine Companions, and a New Philosophy of Cognitive ScienceFrom EverandMinding Dogs: Humans, Canine Companions, and a New Philosophy of Cognitive ScienceNo ratings yet

- Language Acquisition by Steve PinkerDocument38 pagesLanguage Acquisition by Steve PinkerMarius SorinNo ratings yet

- Beauty Care DLLDocument4 pagesBeauty Care DLLErnest Larotin83% (24)

- Thành Trung - Pre - Student - L2Document8 pagesThành Trung - Pre - Student - L2Thành TrungNo ratings yet

- Animals Feel More Than We KnewDocument2 pagesAnimals Feel More Than We KnewRohith GopalNo ratings yet

- Bird-Brain Matches ChimpsDocument2 pagesBird-Brain Matches ChimpspilesarNo ratings yet

- Module 5 About Animals BrainsDocument6 pagesModule 5 About Animals Brainsk.magdziarczykNo ratings yet

- Module 5: About Animal Brains: 5.1 Does The Science of Animal Brains Know It All?Document9 pagesModule 5: About Animal Brains: 5.1 Does The Science of Animal Brains Know It All?Oana DumbravaNo ratings yet

- If We Could Talk With AnimalsDocument4 pagesIf We Could Talk With AnimalsitsshougNo ratings yet

- VOA - California Science Show Explores The DogDocument2 pagesVOA - California Science Show Explores The Dogc_a_tabetNo ratings yet

- The Study of Chimpanzee CultureDocument8 pagesThe Study of Chimpanzee Culturetrinhantran2009No ratings yet

- Writing39c hcp3Document8 pagesWriting39c hcp3api-317131714No ratings yet

- Pride Paper Final 3Document15 pagesPride Paper Final 3api-477139378No ratings yet

- Are You Smarter Than A Chimpanzee?: Test yourself against the amazing minds of animalsFrom EverandAre You Smarter Than A Chimpanzee?: Test yourself against the amazing minds of animalsNo ratings yet

- The Study of Chimpanzee CultureDocument8 pagesThe Study of Chimpanzee CulturetungbonghnNo ratings yet

- IELTS Mock Test 2020 August Reading Practice Test 1Document32 pagesIELTS Mock Test 2020 August Reading Practice Test 119051065 Nguyễn Dương Việt HàNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: IELTS Recent Actual Test With Answers Volume 1Document17 pagesReading Passage 1: IELTS Recent Actual Test With Answers Volume 1Thùy HạnhNo ratings yet

- Domestic Dog Cognition PDFDocument12 pagesDomestic Dog Cognition PDFSsadsNo ratings yet

- Academic Reading Test 2Document9 pagesAcademic Reading Test 2Muhammad Fiaz33% (3)

- Nerea DavidDocument7 pagesNerea DavidjuanpabloNo ratings yet

- Learning by Examples: Checkboxes & Related Question TypesDocument6 pagesLearning by Examples: Checkboxes & Related Question TypesTUTOR IELTSNo ratings yet

- Test Reading Passage 1 Ants Could Teach AntsDocument8 pagesTest Reading Passage 1 Ants Could Teach AntsLÊ NHẬT LINH -Nhóm 8No ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: IELTS Recent Actual Test With Answers Volume 1Document18 pagesReading Passage 1: IELTS Recent Actual Test With Answers Volume 1ziafat shehzadNo ratings yet

- AdvocacydraftDocument11 pagesAdvocacydraftapi-316531346No ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Ape Language StudiesDocument4 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapters: Ape Language Studiesadebayoexcel2006No ratings yet

- HCP - First DraftDocument9 pagesHCP - First Draftapi-279026766No ratings yet

- Ap Final DraftDocument14 pagesAp Final Draftapi-279233311No ratings yet

- So You Think Humans Are Unique: Read The Text and Answer The Questions That FollowDocument7 pagesSo You Think Humans Are Unique: Read The Text and Answer The Questions That FollowNguyễn Thị Hà NgânNo ratings yet

- Why Dogs Are More Like Humans Than Wolves - Ideas & Innovations - Smithsonian MagazineDocument5 pagesWhy Dogs Are More Like Humans Than Wolves - Ideas & Innovations - Smithsonian MagazineRoberto EstevezNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Psychology: Lecture 7 TranscriptDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Psychology: Lecture 7 TranscriptAltcineva VladNo ratings yet

- Animal Language by Michael BalterDocument3 pagesAnimal Language by Michael Balterfragitsa kNo ratings yet

- Readingpracticetest3 v9 623Document15 pagesReadingpracticetest3 v9 623An Ốm NhomNo ratings yet

- Reading Lesson (Multiple Choices) 101021Document34 pagesReading Lesson (Multiple Choices) 101021Quan NguyenNo ratings yet

- IELTS Reading Test 1Document15 pagesIELTS Reading Test 1Marina ShcherbinaNo ratings yet

- 43 Passage 1 - The Culture of Chimpanzee Q1-14Document6 pages43 Passage 1 - The Culture of Chimpanzee Q1-14Lương Lệ DiễmNo ratings yet

- Bruce Bienenstock Documented Essay 5 JulDocument11 pagesBruce Bienenstock Documented Essay 5 JulJessa Mae NazNo ratings yet

- Ants Could Teach AntsDocument4 pagesAnts Could Teach AntsBao Tran TranNo ratings yet

- Ap Draft 1Document7 pagesAp Draft 1api-279199102No ratings yet

- HCP DraftDocument7 pagesHCP Draftapi-291241313No ratings yet

- Psych 3980 Paper - FinalDocument11 pagesPsych 3980 Paper - Finalapi-549334775No ratings yet

- Reading IELTS TestDocument16 pagesReading IELTS TestAnh DangNo ratings yet

- Nef Adv Listening Scripts File06Document2 pagesNef Adv Listening Scripts File06Dani MainNo ratings yet

- Topic Tack 2 WritingDocument14 pagesTopic Tack 2 WritingLê Ngọc ÁnhNo ratings yet

- readingpracticetest3-v9-623Document16 pagesreadingpracticetest3-v9-623seoksoo18023012No ratings yet

- Cats Learn The Names of Their Friend Cats in Their Daily LivesDocument9 pagesCats Learn The Names of Their Friend Cats in Their Daily Livesanca.trainerdesigner.4youNo ratings yet

- Tran 1Document6 pagesTran 1api-316531346No ratings yet

- Animal Behavior Proposal: Introduction+BackgroundDocument20 pagesAnimal Behavior Proposal: Introduction+Backgroundapi-300974290No ratings yet

- PsiAnim13 DogsDocument7 pagesPsiAnim13 DogsAlex DanNo ratings yet

- Is Language Restricted To HumansDocument23 pagesIs Language Restricted To HumansFiriMohammedi50% (2)

- Ants Could Teach AntsDocument4 pagesAnts Could Teach AntsasimoNo ratings yet

- Gut MathDocument2 pagesGut MathYohanna HarunaNo ratings yet

- Do Animals Use Language (The Five-Minute Linguist)Document4 pagesDo Animals Use Language (The Five-Minute Linguist)2167010131No ratings yet

- VaccinationGuidelines2010 PDFDocument34 pagesVaccinationGuidelines2010 PDFNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Loukanikos, Greeces Famous Riot Dog, Barks His LastDocument3 pagesLoukanikos, Greeces Famous Riot Dog, Barks His LastNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Do Puppy Personality Tests Predict Adult Dog BehaviorsDocument2 pagesDo Puppy Personality Tests Predict Adult Dog BehaviorsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Posts Tagged - Dog AggressionDocument5 pagesPosts Tagged - Dog AggressionNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Dr. Nicholas Dodman On Dog Behavior and New Training TechniquesDocument3 pagesDr. Nicholas Dodman On Dog Behavior and New Training TechniquesNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- About LactoscanDocument4 pagesAbout LactoscanNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- WHY PRONG Is WRONG - Physically and PsychologicallyDocument4 pagesWHY PRONG Is WRONG - Physically and PsychologicallyNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Is One Leptospirosis Vaccine Dose Size Really Right For All DogsDocument10 pagesIs One Leptospirosis Vaccine Dose Size Really Right For All DogsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- What Is Transglutaminase or Meat GlueDocument4 pagesWhat Is Transglutaminase or Meat GlueNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- 11 Things Humans Do That Dogs HateDocument4 pages11 Things Humans Do That Dogs HateNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Jealousy in DogsDocument9 pagesJealousy in DogsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Fearful Behavior-Genetics and The EnvironmentDocument3 pagesFearful Behavior-Genetics and The EnvironmentNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Holding Back The Genes - Limitations of Research Into Canine Behavioural GeneticsDocument12 pagesHolding Back The Genes - Limitations of Research Into Canine Behavioural GeneticsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Aggressive Behavior-Inheritance and EnvironmentDocument4 pagesAggressive Behavior-Inheritance and EnvironmentNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- New Evidence Shows Link Between Spaying, Neutering and CancerDocument6 pagesNew Evidence Shows Link Between Spaying, Neutering and CancerNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Aggressive Behavior-The Making of A DefinitionDocument3 pagesAggressive Behavior-The Making of A DefinitionNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- The Biology of Fears and Anxiety-Related BehaviorDocument21 pagesThe Biology of Fears and Anxiety-Related BehaviorNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Is Your Body Language Helping or Confusing Your AnimalDocument5 pagesIs Your Body Language Helping or Confusing Your AnimalNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Grouping Protocol in SheltersDocument10 pagesGrouping Protocol in SheltersNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- What Everyone Should Know About VaccinesDocument3 pagesWhat Everyone Should Know About VaccinesNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Path Characteristics During Walks Are Linked To Dominance Order and Individual Traits in DogsDocument17 pagesLeadership and Path Characteristics During Walks Are Linked To Dominance Order and Individual Traits in DogsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Head PressingDocument2 pagesHead PressingNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Kenneling: This Common Practice May Be Causin Mental Illness in DogsDocument1 pageKenneling: This Common Practice May Be Causin Mental Illness in DogsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Animal Behavior Expert Debunks Dog MythsDocument1 pageAnimal Behavior Expert Debunks Dog MythsNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Latest Cancer InformationDocument1 pageLatest Cancer InformationNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Dog-Appeasing PheromoneDocument3 pagesEfficacy of Dog-Appeasing PheromoneNicholay AtanassovNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument4 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyapi-282290047No ratings yet

- Talent AcquistionDocument14 pagesTalent AcquistionrupalNo ratings yet

- Final MBBS Part I Lectures Vol I PDFDocument82 pagesFinal MBBS Part I Lectures Vol I PDFHan TunNo ratings yet

- Developmental Pathways To Antisocial BehaviorDocument26 pagesDevelopmental Pathways To Antisocial Behaviorchibiheart100% (1)

- Ti Cycles Final PDFDocument20 pagesTi Cycles Final PDFVivek Yadav0% (1)

- Unit Plan-Badminton Jenna Maceachen: Subject Area Grade Level Topic Length of Unit (Days)Document8 pagesUnit Plan-Badminton Jenna Maceachen: Subject Area Grade Level Topic Length of Unit (Days)api-507324305No ratings yet

- Cory Grinton and Keely Crow Eagle Lesson Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesCory Grinton and Keely Crow Eagle Lesson Plan Templateapi-572580540No ratings yet

- Writing Essays On EducationDocument1 pageWriting Essays On EducationAnjaliBanshiwalNo ratings yet

- The Happiness EffectDocument2 pagesThe Happiness EffectClaudene GellaNo ratings yet

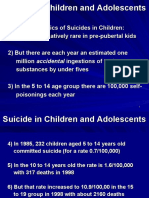

- Suicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalDocument32 pagesSuicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalThambi RaaviNo ratings yet

- FST 430 Innovation and Food Product Development Syllabus Spring 2014 10 30 2013Document7 pagesFST 430 Innovation and Food Product Development Syllabus Spring 2014 10 30 2013Ann Myril Chua TiuNo ratings yet

- 01797johari WindowDocument23 pages01797johari WindowAjay Kumar ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- WillisTodorov (2006) Cognitive BiasDocument7 pagesWillisTodorov (2006) Cognitive BiasrogertitleNo ratings yet

- 1 - Looking at Language Learning StrategiesDocument18 pages1 - Looking at Language Learning StrategiesTami MolinaNo ratings yet

- Appreciative Reframing of Shadow Experience AI Practitioner 2010Document8 pagesAppreciative Reframing of Shadow Experience AI Practitioner 2010Paulo LuísNo ratings yet

- Hriday Assignment Sheet-1: Question-1Document2 pagesHriday Assignment Sheet-1: Question-1kumar030290No ratings yet

- S-TEAM Report: Argumentation and Inquiry-Based Science Teaching Policy in EuropeDocument148 pagesS-TEAM Report: Argumentation and Inquiry-Based Science Teaching Policy in EuropePeter GrayNo ratings yet

- Marketing Yourself Handout (1) : Planning Phase Situation AnalysisDocument6 pagesMarketing Yourself Handout (1) : Planning Phase Situation AnalysisSatya Ashok KumarNo ratings yet

- Music Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesMusic Lesson PlanSharmaine Scarlet FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Bequest of Love: Hope of My LifeDocument8 pagesBequest of Love: Hope of My LifeMea NurulNo ratings yet

- NEW BM2517 Marketing Sustainability For The Next Generation Syllabus - 2024Document9 pagesNEW BM2517 Marketing Sustainability For The Next Generation Syllabus - 2024leongwaihsinNo ratings yet

- Acc EducationalDocument42 pagesAcc EducationalDian AdvientoNo ratings yet

- Cluster SamplingDocument3 pagesCluster Samplingken1919191No ratings yet

- Creating An Integrated ParagraphDocument13 pagesCreating An Integrated ParagraphStuart HendersonNo ratings yet