Professional Documents

Culture Documents

5 Giving Bad News

Uploaded by

Ary Nahdiyani AmaliaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

5 Giving Bad News

Uploaded by

Ary Nahdiyani AmaliaCopyright:

Available Formats

Giving Bad News

~~

Geoffrey H. Gordon, MD

I NTRODUCTI ON

A debilitating or terminal illness, a catastrophic in-

jury, death-these are situations both patients and

physi ci ans face. and t hey are al l si t uat i ons i n whi ch

t he physi ci an must break t he news t o pat i ent s, part -

ners, and fami l y members. The fol l owi ng sect i ons of

this chapter use a diagnosis of cancer to illustrate

some general pri nci pl es t hat can hel p physi ci ans i n

t hi s t ask. Despi t e t hese su, , ooestions, however, t here i s

no one right-or easy-way to present bad news.

Most physicians now inform cancer patients of

their diagnosis. This trend to near-universal disclosure

is the result, in part, of greater public awareness of ad-

vances i n cancer di agnosi s and t reat ment . great er pa-

tient autonomy and self-determination, and greater

physician collaboration with patients to decrease their

i sol at i on and fear and t o mobi l i ze t hei r resources and

copi ng ski l l s. Sel f-report surveys of cancer pat i ent s

si nce 1950 suggest t hat physi ci ans have al ways un-

derestimated patients desires to know their cancer di-

agnosi s and pr ognosi s.

One might expect that the content of the bad news is

overwhel mi ngl y more i mport ant t han t he process wi t h

whi ch i t i s del i vered. Thi s does not appear t o be t he

case. Pat i ent s usual l y have vi vi d recal l of t he physi -

cians manner and style but need repeated explanations

of the facts. For example, the way that parents are told

that their child has a developmental disability or men-

tal retardation affects the emotional state and attitudes

of both child and parents. These parents can distinguish

the message from the messenger, and one-third to one-

half are dissatisfied with how they were given the news.

TECHNI QUES FOR GI VI NG

BAD NEWS

A systematic approach to giving bad news (Table 3-l)

can make t he process more predi ct abl e and l ess emo-

tionally draining for the physician. The process of giving

bad news can be divided into six categories: preparation.

setting. delivering the news, offering emotional support,

providing information, and closing the interview.

Termi nal or Catastrophi c I l l ness

Preparati on: When cancer i s a st rong di agnost i c

possibility. consider discussing it with the patient

earl y i n t he work-up:

DOCTOR: That shadow on your x-ray worries me. It

could be an old scar, a patch of pneumonia, or even a

cancer. I think we should do some more tests to find out

exactly what it is. That way, well be able to plan the best

treatment.

Plan ahead with the patient about how he or she

woul d l i ke t o recei ve t he news:

DOCTOR: Whatever the biopsy shows, 111 want to ex-

plain it carefully-is there someone youd like to have

with you when I go over this?

Knowl edge of t he pat i ent s pri or react i ons t o bad

news can be useful -but not necessari l y predi ct i ve of

t he pat i ent s response. Ideal l y, pri mary and speci al i st

physicians should decide in advance who will give

bad news and arrange fol l ow-up.

Setting: Although it is always best to give bad

news i n person. i f t he pat i ent i s unabl e t o come t o t he

office and asks for t he di agnosi s over t he phone, i t i s

best not t o l i e. Inst ead, begi n a di al ogue t hat provi des

basi c i nformat i on:

DOCTOR: The biopsy showed a type of lung cancer.

The dialogue should conclude with a request to

come t o t he office soon for furt her di scussi on:

DOCTOR: As soon as you can come in, Ill be able to

tell you more about what we need to do next.

Al ways t ake responsi bi l i t y for del i veri ng bad news

yourself. Find a private place to talk with patients.

15

. .

16 / CHAPTER 3

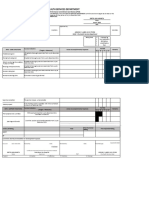

Tabl e 3- l . Tec hni ques f or gi v i ng bad news .

Category

Pr e p a r a t i o n

Technique

For ec as t pos s i bi l i t y of bad news .

Cl a r i f y wh o s h o u l d a t t e n d t h e b a d

news v i s i t .

Cl ar i f y who s houl d gi v e t he bad news .

Se t t i n g

Gi v e bad news i n per s on.

Gi v e bad news i n pr i v at e.

Si t down and mak e ey e c ont ac t .

Del i v er y I d e n t i f y wh a t t h e p a t i e n t a l r e a d y

knows.

Gi v e t he news c l ear l y and unambi gu-

ousl y.

I d e n t i f y i mp o r t a n t f e e l i n g s a n d

concer ns.

Emo t i o n a l Su p p o r t

Re ma i n wi t h t h e p a t i e n t a n d l i s t e n .

Us e empat hi c s t at ement s .

I n v i t e f u r t h e r d i a l o g u e .

I n f o r ma t i o n Us e s i mpl e, c l ear wor ds and c onc ept s .

Summar i z e and c hec k pat i ent s under -

s t a n d i n g .

Use handout s and ot her r esour ces.

Cl os ur e Ma k e a p l a n f o r t h e i mme d i a t e f u t u r e .

As k about i mmedi at e needs .

Sc h e d u l e a f o l l o w- u p a p p o i n t me n t .

Patients in examination gowns should have the oppor-

t uni t y t o dress before recei vi ng bad news. Si t down at

eye level and give them your full attention and concern.

Del i veri ng the News: The next st ep i s t est t he

patients readiness to hear the news. Review the work-

up to date:

DOCTOR: You know we saw that shadow on your chest

x-ray. When we did the CT scan of your chest. we saw a

mass in your lung, and then we looked down your wind-

pipe and took a small sample of your lung. We have the

results of that biopsy now.

Remember that most patients will have consulted an

informal health advisor (a family member, book. or

neighbor) at some point during the illness and will

have al ready devel oped an i l l ness model or cogni -

t i ve map of what i s wrong. what i t means. and what

can be done. It is useful to elicit this model because the

cl i ni ci an can correct t he pat i ent s mi sconcept i ons and

also put the explanations into a context with which the

patient is already familiar. To elicit the model. ask

about t he pat i ent s underst andi ng and concerns:

DOCTOR: What do you already know about this? What

concerns you the most about it?

Allow for silence during the conversation, espe-

ci al l y as emot i ons set i n. Avoi d l ect uri ng about t he

di sease, workup, and t reat ment . Whi l e det ai l ed i nfor-

mation is familiar territory for physicians and helps

reduce their own anxiety, it is rarely helpful for pa-

t i ent s who are heari ng bad news for t he fi rst t i me.

Some patients will immediately ask if the diagnosis

i s cancer and want t o be t ol d prompt l y and di rect l y.

Others will tell the physician, verbally or nonverbally,

to go more slowly. There are at least two ways to slow

down t he message: To grade t he exposure and t o pre-

sent t he hopeful news fi rst .

1. Grade the exposure. Begin with an introduc-

t ory phrase t hat prepares t he pat i ent for t he bad news:

DOCTOR: Im afraid I have bad news for you. . . . This

is more serious than we thought. . . There were some

cancer cells in the biopsy.

The mai n chal l enge wi t h t hi s approach i s t o f i ni sh

wi t h a cl ear, unambi guous st at ement t hat t he pat i ent

has cancer.

2. Present the hopeful message first. This

t echni que i s based on t he fact t hat pat i ent s remember

little of what they are told after the bad news is given:

DOCTOR: Whatever I tell you in a moment, I want you

to remember that the situation is serious, but theres

plenty we can do. Its important that we work closely to-

gether over the next several months. Im sorry, but your

tests were positive for a type of lung cancer.

Once the news sinks in, the patient will typically re-

act wi t h a mi xt ure of emot i ons, concerns, and request s

for i nformat i on and gui dance. Spend a few moment s

on feel i ngs and concerns before gi vi ng more i nforma-

t i on. or pat i ent s may be unabl e t o hear and assi mi l at e

i t . Expl ore t he ori gi ns of t hese feel i ngs and concerns,

because t hey may ari se from mi sconcept i ons based on

experi ences wi t h fri ends or fami l y.

Offering Emotional Support: Getting bad

news i s pri mari l y an emot i onal rat her t han a cogni t i ve

event. Common. immediate emotional reactions are

fear, anger, gri ef, and shock or emot i onal numbness.

An i mport ant chal l enge for many provi ders i s t o re-

mai n present wi t h pat i ent s havi ng st rong emot i onal

react i ons and t o t ol erat e t hei r di st ress. There are no

magi c words or ri ght t hi ng t o say. Si t near t he pat i ent

and use empat hi c st at ement s:

DOCTOR: I can see this is a terrible blow for you. I cant

imagine what it must be like. I want you to know that Ill

continue to be your doctor and work with you on this.

Many pat i ent s fi nd a t ouch on t he hand or shoul der

t o be support i ve and reassuri ng. It i s al so hel pful t o

ask unaccompani ed pat i ent s i f t here i s anyone who

shoul d be cal l ed aft er t hey recei ve t he news.

Some pat i ent s di rect anger at t he physi ci an:

PATIENT: Youd better check again-you doctors are al-

ways making mistakes!

or

PATIENT: Ive always come in for check-ups; why

didnt you find this sooner?

_- -._- __^_ -

GIVING BAD NEWS / 17

Rather than becoming defensive. the physician

should acknowledge that many people in this situation

feel cheated and an,ory. It is important to emphasize

t hat t he di sease. not t he doct or, i s t he enemy and t hat

doctor and patient must work together to fight it.

Patients who are very businesslike or too stunned to

communi cat e t hei r feel i ngs are hard t o eval uat e be-

cause t he degree of di st ress i s not al ways obvi ous.

They may express t hei r gri ef al one or want t o be wi t h

others, such as a friend or minister, before sharing

their feelings with a doctor. The physician can ac-

knowl edge t he di ffi cul t nat ure of t he news and l egi t -

i mi ze fut ure expressi on of feel i ngs:

DOCTOR: I know this is hard to believe. You may have

some feelings about it later that youd like to talk with

me about-Im always ready to listen.

Providing Information: Pat i ent s oft en want t o

know whether they really have cancer, if it has spread,

if it is treatable or curable, and what treatment will in-

vol ve. Some pat i ent s al so want t o know whet her t hey

are goi ng t o di e and, i f so. how much t i me t hey have

left. Even with careful explanations, many patients

are unabl e t o assi mi l at e much i nformat i on at t he t i me

the bad news is given. Effective educational strategies

include using simple, clear words; providing inforrna-

tion in small, digestible chunks; summarizing and

checking the patients understanding of what has been

said; and using handouts or other resources.

Quest i ons shoul d be answered di rect l y and honest l y:

DOCTOR: There are statistics on how long people with

this condition are likely to live, and I can share them

with you, but they are just averages. No one can say for

sure how long you will live.

Closing the Interview: Most patients, even

when initially distraught, compose themselves

quickly with support and direction. The most effective

way t o reach cl osure i s t o provi de a pl an for t he i m-

mediate future. This includes asking patients who else

needs to know the news and if they want help sharing

i t . It i s i mport ant t o reassure pat i ent s t hat t he physi -

cian will still be their doctor even though they will

need to see consultants and have further testing. A fol-

l ow-up appoi nt ment shoul d be schedul ed wi t hi n t he

next several weeks, and pat i ent s shoul d be asked t o

wri t e down quest i ons and concerns t hat t hey or t hei r

families have between visits. Ask about immediate

probl ems such as anxi et y, depressi on, or i nsomni a.

While some physicians like to prescribe a short course

of medi cat i on for sl eepl essness or anxi et y, pat i ent s

should also be told that it is normal to feel upset or to

have t roubl e sl eepi ng aft er recei vi ng bad news.

Death

Some addi t i onal consi derat i ons appl y when not i fy-

i ng fami l y members of t he deat h of a l oved one (see

Chapt er 35). Unexpect ed or t raumat i c deat hs are oft en

t he most di ffi cul t because survi vors are unprepared

and rarel y have a pri or rel at i onshi p wi t h t he not i fyi ng

physician. Physicians should begin by identifying

themselves and their role in the deceaseds care.

Survi vors who must be reached by t el ephone shoul d

be told to come to the hospital prior to the actual death

not i fi cat i on. unl ess t hey speci fi cal l y ask about deat h.

Once gi ven t he news, survi vors may want t o vi ew

the body. This is an important part of the grieving

process and shoul d not be di scouraged. Survi vors are

oft en concerned about whet her t hei r l oved one suf-

fered or was alone at the time of death and whether

t hey coul d have done anyt hi ng t o prevent i t . They can

often be told truthfully that the patient was uncon-

sci ous pri or t o deat h, t here was no evi dence of suffer-

ing, and that maximal efforts were made to help.

People also may need to be reassured that none of

t hei r act i ons hast ened t he pat i ent s deat h.

Depending on the cause of death and comorbid

condi t i ons. t he deceased may be a candi dat e for organ

donat i on. Al t hough some fami l i es obj ect , many ot hers

fi nd comfort i n maki ng an anat omi c gi ft . Many st at es

i nqui re about and record anat omi c donor permi ssi on

on drivers licenses, and families may discover that

the deceased did, in fact, give such consent.

Permi ssi on for aut opsy can al so be request ed at t hi s

time. Once the notifying physician has brought up

these topics, many hospitals have specially trained

staff to work further with families. Some hospitals

and physicians routinely send sympathy cards or

make fol l ow-up cal l s t o recent l y bereaved survi vors.

PROBLEM AREAS

Acceptance

Dont Tell Me if Its Cancer: Some patients

speci fi cal l y request not t o be t ol d t hat t hey have can-

cer. The physi ci an shoul d ask t hese pat i ent s what bad

news would mean to them, or what they are afraid

mi ght happen i f t hey were gi ven bad news.

When pat i ent s ask not t o be gi ven bad news, i t i s

important to explain the rationale for their knowing

t he di agnosi s:

DOCTOR: Your job is to create the best environment for

our medicines and treatments to work. This includes

working with us to plan your treatment, finding which

parts of you are healthy and strong, and which areas still

need some work. Your attitude and interest are important

parts of your treatment; they may help you feel better,

and in some cases, the treatment may work better. We

want you to ask questions about what is happening-re-

member that there are no stupid questions. If it would

help you to talk with someone who has been through

this, please let me know.

Dont Tell Him or Her Its Cancer: Family

members may ask that patients not be told the diag-

18 / CHAPTER 3

nosi s of cancer. Fami l i es shoul d be t hanked for t hei r

concern and reassured that information will not be

forced on the patient. They should also be told that pa-

t i ent s quest i ons wi l l be answered t rut hful l y. Expl ai n

t he rat i onal e for pat i ent s knowi ng t he di agnosi s, and

hel p fami l i es fi nd ways t o pr ovi de emot i onal suppor t .

Some fami l i es wi l l fi nd t hi s di ffi cul t because of pri or

experiences with bad news. Consider eliciting the

fami l ys concerns about what mi ght happen i f t he pa-

t i ent knows. It may hel p t o approach pat i ent s wi t h t he

dilemma:

DOCTOR: Your family has told me that youd prefer not

to be informed about some important aspects of your

care-what are your thoughts about this?

Such an approach can faci l i t at e furt her di scussi on

wi t h t he pat i ent and f ami l y.

I Dont Believe Its Cancer: Some patients are

unabl e t o accept t he di agnosi s, offeri ng such st at e-

ments as I just know it isnt cancer. If I can get some

rest Il l be fi ne. Thi s i s most frust rat i ng when i t de-

l ays t he earl y i mpl ement at i on of pot ent i al l y curat i ve

t reat ment . Physi ci ans oft en use l ogi cal argument s and

dire predictions to persuade patients to agree to

workup and treatment. Paradoxically, this approach

makes many patients more resistant. Instead, the

physi ci an shoul d t ry t o depi ct deni al as a somet i mes

useful , but current l y mal adapt i ve. way of copi ng. Thi s

can be done by explainin, 0 that patients are often of

t wo mi nds:

DOCTOR: Many patients find this kind of diagnosis

hard to believe. I can see that part of you wants to look

on the bright side and stay hopeful. but I wonder if you

dont also have times when you realize that problems

might arise. Lets think about how to proceed if the di-

agnosis is more serious.

The physician should offer to answer any future

quest i ons t he pat i ent mi ght have and expect day-t o-

day vari at i on i n t he pat i ent s abi l i t y t o acknowl edge

t he accuracy of t he di agnosi s. Conversat i ons shoul d

be document ed i n t he pat i ent s chart t o not i fy ot hers

of t he pat i ent s react i on. Somet i mes ant i ci pat i ng fu-

t ure needs hel ps pat i ent s accept t he real i t y of t he di -

agnosi s:

DOCTOR: Lets take a few minutes to think about your

plans if your condition worsens, You may want to make

decisions and plans now. in case youre unable to handle

them in the future.

Different Cultural Values

PIttnudes and beliefs about bad news. death. and

t he expressi on of gri ef are det ermi ned i n part by cul -

tural norms (see Chapter 13). For example, in some

Asi an cul t ural groups, bad news about heal t h-rel at ed

matters is routinely withheld from patients. In some

Et hi opi an cul t ural groups, t he del i very of bad news t o

pat i ent s i s a process t hat i nvol ves t he whol e fami l y.

There are al so cul t ural di fferences i n respondi ng t o

deat h: such ri t ual s surroundi ng pat i ent deat h as open-

i ng wi ndows and burni ng candl es may be di ffi cul t t o

accommodat e i n an acut e care set t i ng. Cul t ural di ffer-

ences bet ween physi ci ans and pat i ent s and t hei r fam-

ilies become problematic when they are not recog-

ni zed as such and are at t ri but ed t o pat i ent or fami l y

uncooperat i veness or psychopat hol ogy. Physi ci ans

who were born and rai sed i n a cul t ural group wi t h be-

havi oral norms t hat di ffer from t hose i n t he syst em i n

whi ch t hey are t rai ni ng or worki ng may fi nd such di f-

ferences hard to reconcile and may experience role

conflicts in caring for patients and families from their

own culture. In this case, consultation with a col-

l eague whose background i s out si de t he subcul t ure

may lend some objectivity.

HOPE 81 REASSURANCE

Patients and families are fearful of losing hope.

Unfort unat el y, many physi ci ans have never l earned

how to offer hope and reassurance along with bad

news. To physi ci ans, hope and reassurance bri ng t o

mind cure. prolonged survival or. at the very least. tu-

mor response. To pat i ent s and fami l i es, hope may i ni -

tially mean cure but later can mean reconciliation

with friends or family who have been estranged. or

t he opport uni t y t o fi ni sh proj ect s, fi nd new sources of

sel f-est eem. see a next bi rt hday or fami l y event . l i ve

wi t hout pai n, or spend val uabl e t i me wi t h l oved ones.

There are several ways physi ci ans can provi de hope

and reassurance at t he t i me of bad news:

Use posi t i ve words. Recogni ze t he di fference be-

tween the uncertain perception of Your scan is

negat i ve and t he cl ari t y of The t est showed your

liver is normal and healthy.

Encourage t he pat i ent t o t hi nk of i l l ness as a chal -

lenge. Most patients will have faced one or more

severe chal l enges i n t hei r l i ves. Invoke t hei r past

successes i n copi ng or ment i on t hose of ot her pa-

t i ent s, sayi ng. for exampl e, Im al ways surpri sed

at how well patients do. . . .

Work t o i mprove pat i ent s funct i on and part i ci pa-

t i on i n t hei r heal t h care. Hel p t hem underst and t hat

t hei r t hought s, at t i t udes. and act i vi t i es affect how

t hey feel , and st ress t he i mport ance of l earni ng t o

rel ax, i dent i fyi ng new sources of pl easure and self-

esteem, and learning coping skills from other pa-

tients.

Hel p pat i ent s l earn how t o face and deal wi t h t hei r

i l l ness real i st i cal l y. Pat i ent s who focus excl usi vel y

on posi t i ve approaches may del ay and i nhi bi t t hei r

own grieving or feel guilty if they cant laugh or

love their cancer away. These patients, and their

fami l i es, may need permi ssi on t o accept and gri eve

their losses. Other patients cope best by consis-

- . ---1-

GIVING BAD NEWS / 19

tently f i ght i ng t he di sease and mai nt ai ni ng a posi -

t i ve focus, i n t he face of al l odds, t o t he very end.

THE HEALTH-CARE TEAM

Al t hough t he physi ci ans rol e i s t o del i ver t he bad

news, ot her heal t h-care t eam members al so pl ay i m-

port ant rol es.

Nurses can be present for t he gi vi ng of bad news,

i nt erpret i t i f necessary, hel p pat i ent s verbal i ze t hei r

feel i ngs and quest i ons, and provi de emot i onal sup-

port. Nurses are trained to evaluate patients emo-

tional and physical responses to treatment. their levels

of comfort and act i vi t y, and t hei r progress t oward ex-

pect ed goal s. Some nurses are al so ski l l ed at ensuri ng

t hat t reat ment deci si ons are congruent wi t h t he over-

al l di rect i on and goal s of care.

Soci al workers are ski l l ed at i dent i fyi ng resources,

enhanci ng copi ng ski l l s, and worki ng wi t h pat i ent s

fami l i es. Chapl ai ns can hel p i n i dent i fyi ng and meet -

ing patients spiritual and emotional needs.

Nutritionists, physical therapists. and clinical phar-

maci st s speci al i zi ng i n pal l i at i ve care can al so make

i mport ant cont ri but i ons t o t he management of seri -

ously ill patients.

Occasi onal l y pat i ent s and fami l i es wi l l need refer-

ral for counseling or other mental health services.

Indi cat i ons for referral i ncl ude prol onged or at ypi cal

grief, particularly when it interferes with daily activi-

t i es or medi cal care; concern about a pat i ent s sui ci de

potential if given bad news; difficulty communicating

within the family or with health-care providers: and

assi st ance i n maxi mi zi ng copi ng ski l l s. Ment al heal t h

referral s are most successful when t he referri ng physi -

cian explains the goals of the referral to the patient

and t el l s t he pat i ent what t o expect :

DOCTOR: This physician may find ways in which you

and I can work together more effectively. Dr. Pierce will

talk to you and then call me to make a care plan.

It i s i mport ant t o ensure fol l ow-up care:

DOCTOR: Id like you to make an appointment to see

me after youve seen Dr. Pierce so we can make some

plans together.

For a physician, checking in with ones own feel-

i ngs i s an i nval uabl e ski l l . Di ssoci at i ng from pai nful

feel i ngs prot ect s physi ci ans psychol ogi cal equi l i b-

ri um and al l ows t hem t o conduct t he t asks of medi cal

care objectively. Experiencing and expressing feel-

i ngs t hat ari se i n t he course of professi onal act i vi t i es,

however, are an important component of physician

well-being. Patients nearly always sense what their

physi ci ans are feel i ng. They oft en val ue demonst ra-

tions of personal caring and express their apprecia-

tion: I knew the doctor really cared about Jimmy

when I saw t ears i n hi s eyes when he was t al ki ng t o

us. In some cases, physi ci ans may need t o i dent i fy

and t al k about t hei r own gri ef wi t h a t rust ed col l eague

before-and after-giving the bad news to the patient

(see Chapter 8).

SUGGESTED READI NGS

Brewin TB: Three ways of giving bad news. Lancet

1991;337: 1207.

Buckman R: How to Break Bud News: A Guide for Health

Care Professionals. Johns Hopkins University Press.

1992.

Butow PN et al: When the diagnosis is cancer: Patient com-

munication experiences and preferences. Cancer

1996;77:2630.

Charlton RC: Breaking bad news. Med J Aust 1992;

157:615.

Cresgan ET. How to break bad news-and not devastate the

patient. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69: 1015.

Fallowfield L: Giving sad and bad news. Lancet

1993;341:476.

Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW: Breaking bad news:

Consensus guidelines for medical practitioners. J Clin

Oncol 1995;13:2449.

Krahn GL, H&urn A. Kime C: Are there good ways to give

bad news? Pediatrics 1993;91:578.

Maguire P, Faulkner A: Communicate with cancer patients:

Handling bad news and difficult questions. Br Med J

1988;41:330.

Muller JH, Desmond B: Ethical dilemmas in a cross-cultural

context: A Chinese example. West J Med 1992;157:323.

Ptacek JT. Eberhardt TL: Breaking bad news: A review of

the literature. JAMA 1996;276:496.

Quill TE. Townsend P: Bad news: Delivery, dialogue, dilem-

mas. Ann Intern Med 199 1;15 1:463.

Tolle SW, Elliot DL, Girard DE. How to manage patient

death and care for the bereaved. Postgrad Med

1985:78:57.

You might also like

- Interact 2Document11 pagesInteract 2Rivan HoNo ratings yet

- Communicating Bad NewsDocument12 pagesCommunicating Bad NewsRudra Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- 3 Delivering Bad NewsDocument11 pages3 Delivering Bad NewsAry Nahdiyani Amalia100% (1)

- 6 Breaking Bad NewsDocument32 pages6 Breaking Bad NewsAry Nahdiyani AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis Typhoid Fever PDFDocument7 pagesPathogenesis Typhoid Fever PDFAry Nahdiyani Amalia100% (1)

- Hydrocephalus in Adults: Questions I Have: (Hi-dro-SEF-ah-lus) What Is Hydrocephalus?Document8 pagesHydrocephalus in Adults: Questions I Have: (Hi-dro-SEF-ah-lus) What Is Hydrocephalus?anntjitNo ratings yet

- Value of CT in The Diagnosis and Management of Gallstone IleusDocument6 pagesValue of CT in The Diagnosis and Management of Gallstone IleusAry Nahdiyani AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Low Dose CTDocument5 pagesLow Dose CTAry Nahdiyani AmaliaNo ratings yet

- PseudoanaurysmDocument6 pagesPseudoanaurysmAry Nahdiyani AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 8 Most Common College DiseasesDocument1 page8 Most Common College Diseasesliezl_alvarez_1No ratings yet

- Aminoglycoside PharmacokineticsDocument13 pagesAminoglycoside PharmacokineticsLama SaudNo ratings yet

- City Health Services IPCR Performance ReviewDocument8 pagesCity Health Services IPCR Performance ReviewLiecel Valdez100% (2)

- ΕΜΠΥΡΕΤΟ EKPADocument25 pagesΕΜΠΥΡΕΤΟ EKPAElenaNo ratings yet

- Hazardous Materials Management Plan SMDocument26 pagesHazardous Materials Management Plan SMdarmayunitaNo ratings yet

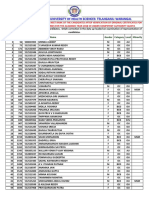

- 1430 Mbbsbdsfinalmeritlist201819 PDFDocument205 pages1430 Mbbsbdsfinalmeritlist201819 PDFVINEETH VinnuNo ratings yet

- Medical Office Management PDFDocument9 pagesMedical Office Management PDFAyessa Joy Tajale100% (1)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis - Lecture SlidesDocument59 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis - Lecture SlidesAndrie GunawanNo ratings yet

- Syndromic Management of Sexually Transmitted InfectionsDocument76 pagesSyndromic Management of Sexually Transmitted Infectionsnamita100% (2)

- Perioperative Nursing Care 1Document17 pagesPerioperative Nursing Care 1Kristian Dave DivaNo ratings yet

- NCM 105 - Infancy NutritionDocument3 pagesNCM 105 - Infancy NutritionCrisheila Sarah PiedadNo ratings yet

- Gradual Dose Reduction Schedule for Psychopharmacological DrugsDocument5 pagesGradual Dose Reduction Schedule for Psychopharmacological DrugsAhmad Mujahid Huzaidi100% (1)

- ACOGAnnualMeeteing Final Program416 1Document218 pagesACOGAnnualMeeteing Final Program416 1BimoNo ratings yet

- Modul 1. Patofisiologi ACSDocument24 pagesModul 1. Patofisiologi ACSFadhilAfifNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Case StudyDocument3 pagesCardiac Case Studydsaitta108No ratings yet

- PEDIATRICS Timetable 5yr, Rot2, Sem1!20!22-NewDocument7 pagesPEDIATRICS Timetable 5yr, Rot2, Sem1!20!22-NewMawanda NasserNo ratings yet

- Questcor ActharDocument6 pagesQuestcor ActharRida el HamdaniNo ratings yet

- Intern Survival Guide Ward 2Document44 pagesIntern Survival Guide Ward 2Keith Swait Zin50% (2)

- Bme ReportDocument15 pagesBme ReportnikitatayaNo ratings yet

- Apert Syndrome - Sultan BaroamaimDocument37 pagesApert Syndrome - Sultan BaroamaimsultanNo ratings yet

- Every Patient Tells A Story by Lisa Sanders, M.D. - ExcerptDocument24 pagesEvery Patient Tells A Story by Lisa Sanders, M.D. - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group76% (17)

- Treatment Outcome and Factors Affecting Time To Recovery in Children With Severe Acute Malnutrition Treated at Outpatient Therapeutic Care ProgramDocument11 pagesTreatment Outcome and Factors Affecting Time To Recovery in Children With Severe Acute Malnutrition Treated at Outpatient Therapeutic Care ProgramMelkamuMeridNo ratings yet

- Education For Parents Regarding Choking Prevention and Handling On Children: A Scoping ReviewDocument8 pagesEducation For Parents Regarding Choking Prevention and Handling On Children: A Scoping ReviewIJPHSNo ratings yet

- September Issue 3 MCJ 36 Pages 2022Document36 pagesSeptember Issue 3 MCJ 36 Pages 2022Sathvika BNo ratings yet

- Infant Feeding Record May 2022Document1 pageInfant Feeding Record May 2022Cyril JaneNo ratings yet

- Crossfit Gym Membership Contract and Receipt TemplateDocument6 pagesCrossfit Gym Membership Contract and Receipt Templatemohit jNo ratings yet

- Low Back Pain Case Study - A Nasty One! But A Good Outcome. - Witty, Pask & BuckinghamDocument4 pagesLow Back Pain Case Study - A Nasty One! But A Good Outcome. - Witty, Pask & BuckinghamermanmahendraNo ratings yet

- AQA Immunity Booklet AnswersDocument6 pagesAQA Immunity Booklet AnswersJames ChongNo ratings yet

- Immunology - Chapter 1 OverviewDocument28 pagesImmunology - Chapter 1 OverviewJJHHJHi100% (1)

- Mei Penyakit UmumDocument1 pageMei Penyakit Umumghaniangga11No ratings yet