Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Practice Problems Solutions

Uploaded by

Rafael Cabral0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views6 pagesIn a two-period game, an incumbent monopolist sets the price for its product. In the rst period, if the incumbent chooses a high price, it earns 200 or 100. If there is no entry, the incumbent will get only 50 if it is the low-cost type. The potential entrant must make an unrecoverable investment if it decides to enter.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIn a two-period game, an incumbent monopolist sets the price for its product. In the rst period, if the incumbent chooses a high price, it earns 200 or 100. If there is no entry, the incumbent will get only 50 if it is the low-cost type. The potential entrant must make an unrecoverable investment if it decides to enter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views6 pagesPractice Problems Solutions

Uploaded by

Rafael CabralIn a two-period game, an incumbent monopolist sets the price for its product. In the rst period, if the incumbent chooses a high price, it earns 200 or 100. If there is no entry, the incumbent will get only 50 if it is the low-cost type. The potential entrant must make an unrecoverable investment if it decides to enter.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Answers to Practice Problems on Asymmetric Information

Ben Polak Econ 159a/MGT522a

Dec 2007

(1) Entry Deterrence (Harbaugh). [Consider a two-period game. In the rst period, an

incumbent monopolist sets the price for its product. In the second period a potential entrant

might enter the market or might stay out. The incumbent is either low cost or high cost. The

entrant does not know which: the incumbent could be low or high cost with equal probability.

In the rst period, if the incumbent chooses to have a high price, it earns 200 if it is low cost or

100 if it is high cost. If it chooses a low price, it earns 150 if it is low cost or 0 if it is high cost.

While it hurts prots in the rst period, setting a low price might discourage entry and boost

prots in the second period. In the second period, if there is no entry, the incumbent will choose

the high price and get 200 or 100 depending on its type. If there is entry, however, competition

will force the incumbent to get only 50 if it is the low-cost type and only 10 if it is the high-cost

type. The entrant must make an unrecoverable investment if it decides to enter the market. Its

prots are -25 if the incumbent is low cost and 50 if the incumbent is high cost. The incumbent

rst decides the rst-period price, then the entrant makes her decision.

(a) Consider a putative separating equilibrium in which the incumbent would charge the low

price in the rst period if it is the low-cost type and would charge the high price if it were the

high-cost type. Show that this is in fact an equilibrium. In particular, what does the potential

entrant believe about the incumbent when seeing each price, and does it enter; and could either

type of incumbent do better by deviating in the rst period.

Answer: To be consistent with the equilibrium actions, the potential entrant must believe that

the incumbent is low cost if she sees a low price in the rst period and believe that the incumbent

is high cost if she sees a high price. In this case, she should enter if and only if she sees a high

rst-period price. Given this, if the low-cost incumbent sticks to the equilibrium, she makes 150

in the rst period and 200 in the second period. If she deviates to a high rst-period price, she

gets 200 in the rst period but (since she would be identied as high cost) only 50 in the second.

Clearly, she won't deviate. If the high-cost incumbent sticks to the equilibrium, she gets 100 in

the rst period and 10 in the second period. If she deviated to the low price in the rst period,

she would get 0 the rst period and (since she would be identied as low cost) 100 in the second.

Clearly, she won't deviate either. So, this is an equilibrium.

(b) Consider a perverse putative separating equilibrium in which the incumbent would charge

the high price in the rst period if it is the low-cost type and would charge the low price if it

were the high cost type. Is this an equilibrium? Explain.

Answer: To be consistent with the perverse putative equilibrium actions, the potential entrant

must believe that the incumbent is high cost if she sees a low price in the rst period and believe

that the incumbent is low cost if she sees a high price. In this case, she should enter if and only if

she sees a low rst-period price. Given this, if the high-cost incumbent sticks to the equilibrium,

she gets 0 in the rst period and 10 in the second period. If she deviated to the high price in the

rst period, she would get 100 the rst period and (since she would be identied as low cost) 100

in the second. Clearly, she will deviate.

(2) In the News. Hillary is considering running for president. A private opinion poll has told

her whether she would have a high or low chance of winning the general election assuming she

is her party's candidate. She has no way to communicate the results of this poll veriably to

other potential candidates: polling numbers are too easy to fabricate. After observing the poll,

however, Hillary can choose whether or not to write another book with her husband. Regardless

of Hillary's chance of winning, writing the book would cost Hillary 1 util. Think of this as loss

of self-esteem.

Al gets to decide whether or not to enter the primary after observing whether or not Hillary

writes the book. Hillary would prefer Al to stay out of the primary race. Al staying out is worth

4 utils to Hillary if Hillary would have a high chance of winning the general election; and Al

staying out is worth 2 utils to Hillary if Hillary would have a low chance of winning the general

election. If Al runs, Hillary gains 0 utils regardless of his chances.

Al only wants to run if Hillary's chances in the general election are bad. Al gets 2 utils from

running if Hillary would have a low chance of winning the general election; and Al gets 1 utils

from running if Hillary would have a high chance of winning the general election. If Al stays

out then his payo is 0. Initially, before seeing whether or not Hillary writes a book, Al thinks

Hillary is equally likely to have a low or high chance of winning the general election.

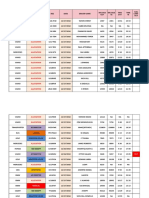

The following table may be helpful.

high-chance Hillary low-chance Hillary

Hillary's book cost 1 1

Hillary's gain if Al stays out 4 2

Hillary's gain if Al runs 0 0

Al's payo if he runs 1 2

Al's payo if he stays out 0 0

Al's initial belief

1

2

1

2

(a) Is there a separating pure-strategy equilibrium in which Hillary makes a dierent decision

whether or not to write the book depending on whether he has a high or low chance

of winning the general election. If such equilibria exist, describe one and show it is an

equilibrium. If no such equilibrium exists, explain why not.

Answer: Notice that Hillary would like Al not to run, and that Al would not like to run if Hillary

has a high chance of winning. The question is asking whether writing the book is sucient a

signal to separate whether Hillary has high or low chances of winning. It is easy to see that

it is not an equilibrium for Hillary only to write the book if he has a low chance of winning.

So consider the supposed equilibrium in which Hillary only writes if he has a high chance of

winning. In this case, if Hillary has a low chance of winning, then he does not write the book, he

2

is recognized as having a low chance of winning and Al enters, leading to a payo for Hillary of

0. If `low-chance Hillary' were to write the book then Al would think Hillary had a high chance

of winning and stay out. In this case, low-chance Hillary would get a payo of 2 1. Thus

low-chance Hillary will deviate.

Now suppose that Hillary can still write the book or do nothing, but he also has a third choice. If

he does not write the book, he can go on Saturday Night Live. This is likely to be a humiliating

experience: its cost to Hillary (regardless of his chance of winning the election) is 3 utils.

(b) Is there a separating pure-strategy equilibrium in which Hillary makes a dierent decision

whether to go on Saturday Night Live, write a book or do nothing depending on whether

he has a high or low chance of winning the election. If such equilibria exist, describe them

and show they are equilibria. If no such equilibrium exists, explain why not.

Answer: Consider a possible equilibrium in which Hillary goes on Saturday Night Live if and

only if he has a high chance of winning, Hillary never writes the book regardless of his chances,

and Al stays out if and only if Al goes on Saturday Night Live. To be consistent with Hillary's

equilibrium choices, Al's beliefs must identify Hillary as having a high chance of winning if and

only if he goes on the show, so Al's decision makes sense given his belief. High-chance Hillary

could deviate and not go on the show but this would lead to Al's running. Such a deviation would

save 3 but it would cost him 4. Meanwhile low chance Hillary could deviate and go on the show

and hence induce Al not to run. But such a deviation would gain him 2 at a cost of 4. Neither

type of Hillary benet by writing the book since it does not deter Al's entering the race. Thus

this is an equilibrium.

(3) (Hard) Nobility Doesn't Advertise. Imagine a country where each person is either upper

class, middle class or lower class, and there is an equal proportion of each type. Regardless of

one's true class, being thought to be upper class is worth 120; being thought to be middle class

is worth 90; and being thought to be lower class is worth 0. One way in which a person can

try to indicate their class to others is by choosing 'to signal'. This signal is a crude 'yes-or-no'

choice; that is, each person can only choose whether to signal or not. The cost of the signal

is 200 for lower-class types; 10 for middle-class types; and 0 for upper-class types. Whether or

not a person chooses to signal, after he or she has made that decision, he or she must take a

compulsory 'high-society' test. The outcome of the test is completely independent of whether or

not a person has signaled. Upper-class types always pass the test; lower-class types never pass;

and middle-class types pass with probability one half.

(a) Suppose there were an equilibrium in which only the middle class signaled. In such an

equilibrium, what must society believe when it sees a person signaling and passing the test;

signaling and failing; not signaling and passing; or not signaling and failing?

Answer: Beliefs must be consistent with the equilibrium. So, in equilibrium, (signal, pass) and

(signal, fail) means the person is middle class: since only middle's signal. Similarly, (no Signal,

pass) means the person is upper class; and (no signal, fail) means the person is lower class.

(b) Show carefully that there is indeed an equilibrium in which only middle-class types

signal.

3

Answer: We need to check the incentive conditions: that is, each type does better doing what

it is doing than by deviating. In this equilibrium, the upper class get 120 if they do not signal,

which is greater than 90 (since they are mistaken for middle class) if they signal. The lower

class get 0 if they do not signal which is better than 90 200 = 110 if they signal (and are

mistaken for middle class). By signaling, the middle class get 9010 = 80. If they do not signal

then, with probability 0:5 they pass (and so get mistaken for upper class) and get 120; and with

probability 0:5 they fail (and so get mistaken for lower class) and get 0. Thus, the expectation

from not signaling if you are middle class is 60. So the middle class are happy to signal.

(c) [hard] Show that there is also an equilibrium in which both middle- and upper-class types

signal. To do this, you may nd it helpful to assume society believes that anyone who does not

signal and who passes the test is middle class.

Answer: In equilibrium, the probability that a person is (upper class, signals and passes) is 1=3

since all upper class people signal and pass. The probability that a person is (middle class, signals

and passes) is 1=6 since all middle class people signal but only half of them pass. So (by Bayes

rule), the probability that a person who signals and passes is upper class is (1=3)=(1=3 +1=6) =

2=3; and the probability that they are middle class is (1=6)=(1=3+1=6) = 1=3. That is, if society

sees someone signal and pass then society thinks that person is upper class with probability 2=3

and middle class with probability 1=3. Similarly, in this putative equilibrium, If society sees

someone signal and fail, then they must be middle class; and non-signalers must be lower class.

Now lets check deviations. In equilibrium, the upper class get 2=3(120) + 1=3(90) = 110.

If an upper class person deviates and does not signal, he still passes and so gets 90 (by our

assumption). So the upper class are happy to signal. In equilibrium, a middle class person gets

0:5[2=3(120) + 1=3(90)] + 0:5[90] 10 where the rst bracket is if he passes and the second is if

he fails. If he deviates and does not signal then he gets 0:5[90] +0:5[0] where the rst bracket is

if he passes (and so is thought middle class by our assumption) and the second is if he fails (and

so is thought lower class). The former total 90 whereas the latter is 45, so the middle class is

happy to signal. Finally, since the cost of signaling is 200 if you are lower class, nothing could

ever induce you to signal.

(4) An Auction. Alice and Bob would both like to own the same hand-written and signed

manuscript of a Frost poem. The manuscript is worth $5 million to Alice and worth $3 million

to Bob. The present owner of the manuscript proposes the following method of sale, known

as a `second-price auction'. Alice and Bob will each simultaneously write down a `bid' for the

manuscript. Let b

A

be Alice's bid, and let b

B

be Bob's bid. The manuscript will go to the

person whose bid is highest, and that person will have to pay the other person's bid. If the

bids are tied, then a fair coin will be tossed to decide who gets the manuscript, and that person

will have to pay the tied bid. In either case, the person who does not get the manuscript pays

nothing.

Here then is Alice's payo function in this game (in $ millions):

u

A

(b

A

; b

B

) =

8

<

:

5 b

B

if b

A

> b

B

0 if b

B

> b

A

1

2

(5 b

B

) if b

A

= b

B

Everything above is common knowledge to the players (in particular, they know each other's

4

payos). There are no other bidders. Negative bids are not allowed. [Notice that you do not

need to answer parts (c) and (d) in order to answer part (e).]

(a) Write down Bob's payo function u

B

(b

A

; b

B

).

Answer: Bob's payo function is

u

B

(b

A

; b

B

) =

8

<

:

3 b

A

if b

B

> b

A

0 if b

A

> b

B

1

2

(3 b

B

) if b

A

= b

B

(b) What are Alice's best responses to b

B

= 2? What are Alice's best responses to b

B

= 10?.

Answer: In the rst case, Alice will pay 2 if she wins the auction. Since the good is worth 5

to her, she wants to win. Thus any bid greater than 2 is a best response. In the latter case, she

would pay 10 she wins. Thus any bid less than 10 (to ensure she loses) is a best response.

(c) Are the following strategy proles equilibria of the game: (5; 3); (4; 7); (2; 3); (10; 0) where

the rst number is b

A

and the second is b

B

. Explain your answer.

Answer: The prole (5; 3) is an equilibrium: Alice's payo is 53 = 2, and Bob's is 0: If Alice

deviates by some b

0

A

> 3, it make no dierence to her payo. If she deviates by some b

0

A

< 3,

she gets 0: If she deviated by bidding 3 she would get a payo of 1. If Bob deviates by bidding

equal or more than 5, then he gets a negative payo. If he deviates to a bid less than 5, his

payo is still 0.

The prole (4; 7) is not an equilibrium. For example, Bob's payo here is 3 4 = 1, he

wins the good but pays `too much' for it. He can deviate to (say) 0 and get a payo of 0.

The prole (2; 3) is not an equilibrium. For example, Alice's payo here is 0. She can deviate

to (say) 9 and get a payo of 5 3 = 2.

The prole (10; 0) is an equilibrium. Alice's payo is 5 and Bob's is zero. No matter what

she bids, provided it is greater than 0 she gets the same payo. If she bids zero it makes her

worse o. The only way for Bob to change his payo is for him to bid more than 10. This would

yield a negative payo.

(d) Are there any equilibria in which Bob wins the manuscript? Explain.

Answer: The prole (0; 10) is an equilibrium: Alice's payo is 0, and Bob's is 3: The reason

it is an equilibrium is the same as for (10; 0) mutatis mutandis.

(e) Which (if any) of Alice's and Bob's strategies are strictly dominated. Which (if any) are

weakly dominated? Explain concisely but carefully.

5

Answer: No strategy for either player is strictly dominated. For example, for any two bids

b

A

> b

0

A

of Alice, u

A

(b

A

; b

B

) = u

A

(b

0

A

; b

B

) if b

B

> b

A

. But for each player, bidding her own

value is weakly dominant. Let's just show this for Alice (the argument for Bob is similar). First

consider a bid b

0

A

> 5.

u

A

(b

0

A

; b

B

) for b

0

A

> 5 u

A

(5; b

B

)

5 b

B

5 b

B

if b

B

5

negative 0 if b

0

A

b

B

> 5

0 0 if 5 > b

0

A

Next consider a bid b

00

A

< 5.

u

A

(b

00

A

; b

B

) for b

00

A

< 5 u

A

(5; b

B

)

0 0 if b

B

5

0 5 b

B

if b

0

A

< b

B

< 5

(5 b

B

) =2 5 b

B

if b

B

= b

00

A

5 b

B

5 b

B

if b

B

< b

00

A

6

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Minds Eye Theatre Werewolf The Apocalypse (10101091) - 1Document762 pagesMinds Eye Theatre Werewolf The Apocalypse (10101091) - 1Mic100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Complete Synthesizer BookDocument85 pagesThe Complete Synthesizer Bookchuckrios100% (5)

- Live Sound BasicsDocument30 pagesLive Sound BasicsAlexandru Gorgos100% (17)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- MERP - Angmar 2nd EditionDocument161 pagesMERP - Angmar 2nd EditionGon_131378% (18)

- 1766481-The Underwater ShrineDocument11 pages1766481-The Underwater ShrineGerwin LubbersNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Shadowrun Fillable Character SheetDocument2 pagesShadowrun Fillable Character SheetAnonymous FgOeQ5uiNo ratings yet

- Incarnate RPG PlaytestDocument362 pagesIncarnate RPG PlaytestJason Patterson100% (1)

- The Art and Meaning of MagickDocument47 pagesThe Art and Meaning of MagickBianca LunguNo ratings yet

- The Art and Meaning of MagickDocument47 pagesThe Art and Meaning of MagickBianca LunguNo ratings yet

- Shot Put TutorialDocument15 pagesShot Put TutorialSatish100% (1)

- The Initiation Rite in The Bwiti Religion (Ndea Narizanga Sect, Gabon)Document17 pagesThe Initiation Rite in The Bwiti Religion (Ndea Narizanga Sect, Gabon)Rafael CabralNo ratings yet

- .Basketball Rules and Regulation.Document30 pages.Basketball Rules and Regulation.Evelyn AbreraNo ratings yet

- Magickal Curriculum PDFDocument99 pagesMagickal Curriculum PDFRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Kotronias Vassilios The Safest Scandinavian 0ADocument353 pagesKotronias Vassilios The Safest Scandinavian 0Aдима100% (9)

- Dragon Kings Savage Worlds PDF Rules Supplement v2Document18 pagesDragon Kings Savage Worlds PDF Rules Supplement v2Tim RandlesNo ratings yet

- Demystifying MaxmspDocument47 pagesDemystifying Maxmspde_elia_artista100% (4)

- Quiz Bowl ScriptDocument3 pagesQuiz Bowl ScriptShawtii GanadeNo ratings yet

- Dragons of The Red Moon Epic Encounters For 5e.Document93 pagesDragons of The Red Moon Epic Encounters For 5e.Sasha50% (2)

- Legends of The Untamed WestDocument4 pagesLegends of The Untamed Westtedehara100% (1)

- Akkadian Literary Old Babylonian (Izre'El & Cohen)Document131 pagesAkkadian Literary Old Babylonian (Izre'El & Cohen)Rafael CabralNo ratings yet

- How To Reassess Your Chess PDF DownloadDocument2 pagesHow To Reassess Your Chess PDF DownloadDaniel Vieyra II33% (3)

- Biblia Bartolomeu ANANIADocument28 pagesBiblia Bartolomeu ANANIAIon BotezatuNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Online Gaming Habits in The Academic Performance Among Hsu StudentsDocument52 pagesThe Impact of Online Gaming Habits in The Academic Performance Among Hsu StudentsAnne Tepace100% (1)

- frazier1942Document15 pagesfrazier1942Rafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Soundscape PsychoacousticsDocument7 pagesSoundscape PsychoacousticsEl KetoNo ratings yet

- harrietDocument122 pagesharrietRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- 08 Labelle Lucier Voice PDFDocument10 pages08 Labelle Lucier Voice PDFRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- frazier1944Document19 pagesfrazier1944Rafael CabralNo ratings yet

- FR Neonfaust - Practical Applications of The Chaossphere PDFDocument3 pagesFR Neonfaust - Practical Applications of The Chaossphere PDFyogimanmanNo ratings yet

- Louis-Ferdinand Celine-Death On Credit - Oneworld Classics LTD (2009)Document477 pagesLouis-Ferdinand Celine-Death On Credit - Oneworld Classics LTD (2009)Rafael Cabral100% (4)

- Engineering and TechnologyDocument2 pagesEngineering and TechnologyRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Open FrameworksDocument59 pagesOpen FrameworksJeff GurguriNo ratings yet

- Twister P2P Microblogging PlatformDocument12 pagesTwister P2P Microblogging PlatformLeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Random StuffDocument2 pagesRandom StuffMuhammad Haseeb JavedNo ratings yet

- Bang BookDocument169 pagesBang BookMyke BulvaiNo ratings yet

- Studying Microscopic Peer-to-Peer Communication Patterns: Peter A. Gloor Daniel OsterDocument12 pagesStudying Microscopic Peer-to-Peer Communication Patterns: Peter A. Gloor Daniel OsterRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning, Neural and Statistical ClassificationDocument298 pagesMachine Learning, Neural and Statistical ClassificationElias JuarezNo ratings yet

- Reimagining Garden Cities FinalDocument40 pagesReimagining Garden Cities FinalRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Antiaging DrugsDocument16 pagesAntiaging DrugsHarish KakraniNo ratings yet

- Working Through Screens BookDocument143 pagesWorking Through Screens BookyoutreauNo ratings yet

- RasayanaDocument6 pagesRasayanahari haraNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Instrument For Interactive, On-The-Fly Machine LearningDocument6 pagesA Meta-Instrument For Interactive, On-The-Fly Machine LearningRafael CabralNo ratings yet

- Athletes DilemaDocument2 pagesAthletes DilemaAlfonse FeminoNo ratings yet

- Scus 941.63Document2 pagesScus 941.63Abdur RafiNo ratings yet

- ICAR Zonal and Inter Zonal Sports Tournament 2022Document5 pagesICAR Zonal and Inter Zonal Sports Tournament 2022R'v BaraiyaNo ratings yet

- Megmeet Mp113-w Led Power Supply SCHDocument1 pageMegmeet Mp113-w Led Power Supply SCHPa3lo Pa3loNo ratings yet

- Battle Line RulesDocument6 pagesBattle Line RulesJeffrey BarnesNo ratings yet

- Mr-Men Lesson Plan PDFDocument5 pagesMr-Men Lesson Plan PDFGabrielaNo ratings yet

- Pokémon Ruby GamesharkDocument10 pagesPokémon Ruby GamesharkRyan Afif DwinandaNo ratings yet

- Presentación 1Document12 pagesPresentación 1Alejandro Valdivia HernandezNo ratings yet

- 008 Exercising PrepositionsDocument4 pages008 Exercising Prepositionsb_bita4000No ratings yet

- City of Fulton Parks and Recreation Program and Activity Guide - Fall 2019Document16 pagesCity of Fulton Parks and Recreation Program and Activity Guide - Fall 2019CityofFultonMoNo ratings yet

- Yggdra Union - We'Ll Never Fight Alone FAQ - Walkthrough For Game Boy Advance by Lufia - Maxim - GameFAQsDocument271 pagesYggdra Union - We'Ll Never Fight Alone FAQ - Walkthrough For Game Boy Advance by Lufia - Maxim - GameFAQsJorge Acevedo0% (1)

- MTAP Grade 6 National 2014Document1 pageMTAP Grade 6 National 2014Gil Kenneth San Miguel100% (1)

- KD Kakuro 5x5 v3 s2 b065Document3 pagesKD Kakuro 5x5 v3 s2 b065RADU GABINo ratings yet

- 2017 Mariners MiLB Season ReviewDocument65 pages2017 Mariners MiLB Season ReviewMarinersPRNo ratings yet

- Aron Nimzowitsch Wins The Dresden Tournament of 1926Document6 pagesAron Nimzowitsch Wins The Dresden Tournament of 1926navaro kastigiasNo ratings yet