Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Halemba DonahoeFinalReport

Uploaded by

Agnieszka Halemba0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views35 pagesOriginal Title

Halemba-DonahoeFinalReport

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views35 pagesHalemba DonahoeFinalReport

Uploaded by

Agnieszka HalembaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 35

Agnieszka Halemba Brian Donahoe

University of Leipzig Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology

Leipzig, Germany Halle/Saale, Germany

halemba@uni-leipzig.de donahoe@eth.mpg.de

Research report for WWF Russia Altai-Saian Ecoregion

Local perspectives on hunting and poaching

1

Contents

Summary.... 2

Introduction... 3

Research Process and Methodology.... 3

Research Sites... 3

Timing... 4

Research Methods.... 4

Research difficulties. 6

General information about the population of the research region 8

Who is a hunter and who is a poacher?....................................................................................................................................... 10

Tyva. 10

Altai.. 12

Reasons for hunting and morally appropriate hunting 15

Tyva.. . 16

Altai.. 16

Attitudes to animals. 19

Attitudes to nature protection areas.. 24

Altai. 24

Tyva..... 26

Recommendations 27

Co-operation with local communities in establishing information and education strategies 27

Legislative and institutional reform.. 29

Support for development of economic activities (tourism, animal husbandry, alternative economic activities) . 30

Support for monitoring of hunting activities and enforcement of regulations 32.

Further research. 32

Concluding remarks 33

Literature cited 33

2

Summary

Hunting has always played an important role in the lives of the indigenous nomadic peoples of southern Siberia. Nowadays, however, hunting has

become a target of environmentalists, especially those concerned with the protection of wildlife biodiversity. As a result, many indigenous peoples

find themselves in a situation in which their traditional hunting activities have come to be considered poaching.

One of the main assumptions behind some initiatives to reduce hunting is that people hunt out of economic need, and if they had alternative

forms of income generating activities, they would hunt less or even not at all. This research project was designed in part to test that assumption in

the southwestern section of the Altai-Saian Ecoregion. This region is notable for its flagship species (snow leopard and argali sheep). It also

includes a number of existing and proposed protected areas, and is a target area for the development of various WWF pilot projects.

The report is based on social anthropological research conducted in March and April 2008. It examines local perspectives on issues related to

legal and illegal hunting and on the effectiveness of existing mechanisms of nature protection.

Main findings

The cultural reasons for hunting far outweigh economic considerations.

While local hunters and herders are exceptionally knowledgeable about the location and migration habits of various species, their

perceptions of the relative health of the populations are easily biased toward overestimation.

The emic (i.e., as understood by the local population) definitions of poaching and proper hunting have nothing to do with legal permissions

or the lack of them. Rather, poaching and proper hunting are differentiated along the lines of the quantity and types of animals taken, hunting

methods, purpose for hunting, and whether certain customs are observed or not.

The closer people live to existing protected areas and the more actual experience they have of them, they less supportive they are.

The overwhelming majority of people agreed that tourism should be developed further, but most oppose hunting tourism (for trophy).

Recommendations

Effective community-based wildlife management requires intimate community involvement; a sense of ownership; and sensitivity to cultural

considerations. While it will be impossible to stop illegal hunting altogether, a comprehensive program incorporating the following components

could reduce hunting and instill in local residents a renewed sense of control over and responsibility for the wild animal resources in their areas:

Co-operation with local communities in establishing information and education strategies

Legislative and institutional reform

Support for development of economic activities (tourism, animal husbandry, alternative economic activities)

Support for monitoring of hunting activities and enforcement of regulations

Further research

3

Introduction

With the intention of developing a model program to reduce illegal hunting by creating new protected areas and stimulating alternative income-

generating activities, WWFs Altai-Saian Ecoregion office commissioned a study to assess local attitudes to wild animals (especially endangered

species such as snow leopard, argali sheep, and ibex), hunting, poaching, and nature protection among people living on the Russian side of the

transboundary region where the republics of Altai and Tyva share a border with Mongolia. The project was directed by Dr. Agnieszka Halemba of

the University of Leipzig, Germany, with the assistance of Dr. Brian Donahoe of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle,

Germany.

Hunting has always played an important role in the lives of the indigenous nomadic peoples of southern Siberia. Nowadays however, with

increasing populations, high-powered firearms and other more technologically advanced hunting methods, improvements in transportation bringing

supply and demand for wild animal products closer, encroachment on habitat by expanding urban areas and other forms of industrial development,

hunting is fast becoming a target of environmentalists, especially those concerned with the protection of wildlife biodiversity. As a result, many

indigenous peoples find themselves in a difficult situation in which their traditional hunting activities have come to be considered poaching, and

they are blamed for the decline in wildlife, yet they often see themselves as the ones living close to nature and in harmony with it.

One of the main assumptions behind NGO projects to reduce hunting is that people hunt out of economic need, and if they had alternative forms of

income generating activities, especially if they had regular paid work, they would hunt less or even not at all. This research project was designed in

part to test that assumption. The projects main aim has been to elucidate local attitudes towards hunting among people living in the western section

of the Altai-Saian Ecoregion. The project also focused on the local perception and effectiveness of existing mechanisms of nature protection, both

generated by the state as well as by various NGOs and international organisations active in the region. The information gathered though the

projects activities and reported here is intended to provide background information necessary for developing culturally sensitive and viable

programmes aimed at nature protection, economic development, and preservation of wild animal populations in the region. To ensure anonymity of

the respondents, no pictures of people are included in this report.

Research Process and Methodology

Research sites

The research region in general was chosen according to WWF specifications. The precise selection of villages and camps for investigation

accounted for local variations of such factors as: size of settlement; distance from main roads; variety and density of wild animal populations;

distance from existing or planned nature protection areas. The research team conducted surveys and interviews both in herders camps and in

villages of different sizes, both those located next to main roads as well as in more remote areas. The project targeted communities living in and

around existing and proposed protected areas, including the Shavlinskii zakaznik (wildlife refuge), a segment of the Sailugem range proposed for

4

inclusion in a new protected area, and a proposed transboundary migration corridor for argali sheep around the area where the borders of Mongolia,

Tyva, and Altai meet.

Halembas research focused on villages and herders camps in the Kosh Agach district of the Republic of Altai as well as in the village of Chibit in

the Ulagan district. For purposes of this project, the research area in Altai can be divided into three parts:

1. Villages (and respective camps) located next to the international road of Chuiski Trakt with relatively easy access to animal-rich territory

2. Villages (and respective camps) in the steppe or close in the surrounding mountains, located further away from animal-rich territories and/or

located close to border posts

3. Villages (and respective camps) located away from the main communication routes, with easy access to animal-rich territories.

Donahoe worked in the Mngn-Taiga District of southwestern Tyva, with a particular focus on the Mgen-Bren municipality, which shares

borders with both the Kosh-Agach district and Mongolia. While the Kargy municipality is the larger and more populated part of Mngn-Taiga

district and its main town, Mugur-Aksy, is the district capital, Donahoe focused primarily on the Mgen-Bren municipality for the following

reasons: it contains more recognized snow leopard, argali, and ibex habitat; the proposed argali migration route crosses from Mongolia into the

Mgen-Bren area; the region is more remote than Mugur-Aksy (no land-based nor cellular telephone connections); it is more economically

depressed with fewer employment opportunities, therefore would be a better place to test the assumption that people hunt out of economic need.

Below, we sometimes use Tyva and Altai while presenting differences in the results of this study. It is important however to remember that we

do so for the sake of brevity and convenience the results of this report refer only to those areas in Tyva and Altai described above.

Timing

The field activities were intended to be carried out in March 2008, simultaneously in Kosh Agach and in Mngn-Taiga. While Halemba was able

to stick to the original schedule, Donahoes phase of the research project was significantly delayed because of difficulties in obtaining the necessary

permission to travel to the border-zone region of Mngn-Taiga. He was not able to go to Mngn-Taiga until the second week of April. Actual

fieldwork was conducted 14-27 April.

Research Methods

Prior to field research, the researchers devised a detailed survey form (See Appendix), which was intended as the principal research instrument.

These were to be filled in by the researcher together with a respondent. However, soon into a research processes it became clear that the issue in

question is too sensitive to conduct research exclusively in this way, especially in the Republic of Altai (see below). Although the survey forms

were used, most of the information was gathered during structured interviews when the survey form was a staring point for a conversation. Much

information was gathered also through informal talks. As both researchers have conducted long-term fieldwork on other topics in Altai and Tyva

5

previously, there were numerous opportunities to discuss freely the subject in question with long term friends and acquaintances. In some cases in

Tyva, survey forms were given out and were self-administered, without an accompanying interview.

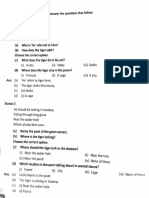

The survey and the interviews addressed a number of questions divided into the following subgroups:

Local understanding of nature and perspectives on human-animal relations

How is nature understood? Do people perceive themselves as an integral part of nature, or as external to and separate from nature?

How do people understand their relations with nature? It is in terms of exchange? Domination? Subordination? Responsibility? Cooperation?

Struggle? Unity?

Are there different circumstances under which those relations between people and nature change/take different forms? What are those

circumstances?

How are wild animals seen in this context? Are there different groups of animals towards which the attitudes are shaped differently? If so,

what factors influence such differences?

Which species are seen locally as endangered and/or worth protecting? How do local people assess the relative health, stability, and

sustainability of wild animal populations? Do people recognise that over-hunting is a problem?

The social, economic and cultural significance of hunting

Who hunts? What are the various social, cultural and economic positions of those who hunt?

How is the social, cultural and economic position of hunters perceived locally?

What kind of social and cultural capital, if any, one can accumulate through hunting?

What kind of social and cultural capital, if any, is required for ones hunting activities to be perceived as legitimate?

Under what circumstances, if any, would people refrain from hunting?

What kinds of animals are being hunted?

What are the attitudes towards hunting different types of animals?

For what purposes are the animals hunted (subsistence, sale, entertainment, cultural reasons, e.g. as form of male bonding or proof of

masculinity)? What parts of the given animals are mostly valued and for which reasons?

Concepts of legality and illegality in relation to hunting

What kind of hunting is locally seen as legitimate?

Which hunters are seen as legitimate? What legitimates them?

Are there animals that are perceived as legitimate to hunt, and others that are perceived as illegitimate (forbidden) to hunt?

What is locally considered illegitimate hunting (i.e., what is poaching in the eyes of locals)?

What is the relation between a local understanding of illegitimate hunting and the definition of poaching as present in the state laws?

6

Who are in local opinion real poachers, representing the greatest threat to wildlife?

How do local people respond to the idea of trophy hunting, sports hunters from outside the region, and hunting tourism?

Relations with nature protection initiatives and state organs

Do hunters have hunting cards (okhotnichii bilet)? If not, why not? Under which circumstances would hunters consider applying for a card?

Do hunters with hunting card apply for hunting licenses?

How is hunting with official licenses versus without ones perceived?

Do they feel treated fairly by state organs regulating hunting? If not, why?

What is their perception of official organisation of hunting?

What is their perception of old and new protected areas? Are protected areas seen as allies or as enemies to local people in general and to

local hunters in particular? Are protected areas considered useful in any respect?

If people accept that at least some animal species should be protected, what would be the local suggestion as to implementing protection

measures? How, in their opinion, should protected areas be organised and managed?

On the basis of responses to these questions, we present below a report on local peoples perception of hunting, their opinion on what types of

activities are most dangerous for environment and their suggestions for improving the situation. We have concentrated on understanding the point of

view of the local people, especially local hunters without any documents or permissions, their perception on who hunts and who poaches and their

opinion on possible ways of improving the existing situation. Below, we use the term hunter for anyone who hunts, regardless of whether he has a

hunting card (okhotnichii bilet), license (for hunting a particular type of animal at a given time) or permission to carry a gun. If the opinions of

different groups of hunters diverge, we make it clear in the text.

Research difficulties

Interestingly, in the two areas (Altai and Tyva) researchers met with noticeably different reactions from informants. In the Altai case, people were

very reluctant to discuss the subject of hunting, particularly of illegal hunting or poaching. Halemba feels that she could conduct interviews with

hunters without licenses only because she is well-known in the region and was introduced to many of them through close friends and acquaintances.

Even then, many interviews were conducted outside of houses, in closed cars, or in secluded places. In the Tyva case, informants seemed much

more open and willing to talk, once they were guaranteed anonymity, of course. This difference is most likely related to differing perceptions of

effectiveness of poaching prevention measures in the two areas. In Kosh Agach, this reluctance has been probably caused by the recent

intensification of official anti-poaching measures (frequent check up, increase in fines, introduction of prison terms for illegal hunting) as well as

police searches for unregistered guns. The reluctance to talk freely reflects caution that in turn can be seen as an indication that enforcement

mechanisms in Altai are proving to be effective. In Mngn-Taiga, the overwhelming sense is that the inspectors and others responsible for

monitoring hunting are ineffective and therefore do not instill much fear. There is the sense that enforcement is not done well enough (this point was

7

often made by explicit comparison to the perceived effectiveness of enforcement measures just across the border in Altai), and that in fact it would

be good if enforcement were actually stricter.

Moreover, in Altai some people have heard about the old conflict between the Hunting Department (okhotupravlenie) of the Republic of Altai and

WWF. Apparently in 2004 WWF Altai-Saian Ecoregion accused the Hunting Department of the Republic of Altai of organising illegal hunting trips

in the district of Kosh Agach. In response, the head of the Hunting Department, Viktor Kaimin wrote an open letter accusing international

organisations (including explicitly WWF) of anti-Russian activities

1

. He claimed that foreign NGOs try to hinder the creation of connection between

Russia and China, we quote to stop Russias, with her immense resources of gas and oil, access to the east, to stop the development of hydropower,

and the extraction of natural resources in the border region of the Republic of Altai this is the main aim of the Western states that sponsor

international nature protection organisations. This blocking of Russias development is, according to the author, done precisely by creating various

types of nature protection territories along Russias borders. Although the precise content of this and similar statements might be not know to local

people, quite noticeable mistrust towards international organisations could be felt in the region. Halemba has head a few times that WWF is

sponsored by CIA and that it employs American spies. This obviously does not make the research process any smoother, as, for ethical reasons, we

informed people that we were compiling this report for WWF.

The difficulties in the Mngn-Taiga district were more logistic than attitudinal. So for

example, as Donahoes fieldwork was delayed, he was in the Mngn-Taiga district at a

difficult time for two reasons: herders were in the process of moving from their winter to

their spring camps, so in several cases he came across campsites that had been evacuated

just the day before. Without accurate information as to the location of the spring camps, he

generally did not try to follow. The other seasonal problem was that river ice was melting,

making the crossing of rivers treacherous. Moreover, in several cases, he would arrive at

an aal (homestead / campsite) to find that there was no one to talk to because they were

out with the animals. In addition, there is no access to benzene in the Mgen-Bren

municipality. Donahoe had to purchase all the benzene he felt would be necessary in

Mugur-Aksy,. Because of that, return trips to aals where he was unsuccessful were not

practical.

Landscape of Mgen-Bren municipality

1

See http://www.gorno-altaisk.ru/archive/2006/27/005.htm and

http://hghltd.yandex.net/yandbtm?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.mk.ru%2Fnumbers%2F1382%2Farticle43345.htm&text=%E2%E8%EA%F2%EE%F0%20%EA%E0%E9%EC%

E8%ED#YANDEX_0 accessed on the 4.06.2008

8

General information about the population of the research region

The Mngn-Taiga district occupies an area of 4400 km2 with population density 1,4

person/km2. It is divided into two main sumons, or municipalities, Kargy, with its

administrative center Mugur-Aksy; and Mgen-Bren, with its administrative center,

Kyzyl Khaia. Kargy is the larger municipality in terms of both area and population, with

a population of 4683, while Mgen-Bren has a population of 1404. In addition, recently

a third sumon, Toolailyg, with a population of 160, was established.

2

The population of

Mngn-Taiga district is virtually 100% ethnic Tyvan.

Mugur-Aksy

In comparison to Mngn-Taiga, Kosh Agach district (territory 19845 km2) is quite

populated and diverse. The number of inhabitants is over 17 000. Roughly half of the

population is Kazakh, the other half being Altaian-Telengit (one of the officially recognized

indigenous small-numbered peoples of Russia), and there is a small number of Russians

and other nationalities.

Most of the hunters are Altaian and there is a general agreement in the district that Kazakhs

hunt less and if they do, they are usually introduced to hunting by Altaian friends. There are

two exceptions to this rule:

1. Kazakhs, as most of the population of Kosh Agach (including children and women) hunt

marmot.

2. Quite a few Kazakhs living in Dzhazator village also hunt bigger animals. They are also

involved in illegal trade of animal products.

Kosh Agach

2

These populations figures are as of January 2008, as provided by the Mngn-Taiga Office of Statistics in Mugur-Aksy.

9

One additional peculiarity has to be noticed with regard to the local Altaian population, as it is important for our recommendations.

In 2000 the Telengits were added to the official list of indigenous small-numbered peoples of the Russian Federation (korennye malochislennye

narody below KMN). According to informal estimates (done by researchers and by local leaders), there should be between 10,000 and 17,000

Telengits living in the Ulagan and Kosh Agach districts of the Republic of Altai. However, during the 2002 census only 2,398 people in the

Republic of Altai declared themselves as Telengit. This was due to complex political reasons, most importantly a media campaign run from the

republican center that encouraged people to declare themselves Altaian. Nevertheless, despite such a low number of Telengits registered during the

last census, the Telengit identity in the district is strong. There is a non-governmental Association of the Telengits, whose members go

sometimes to great pains to establish their legal status as members of this KMN (the procedure involves court hearings) and the official Center for

Telengit Culture sponsored by the districts administration. As in the Russian legal system it is only the small-numbered indigenous peoples that are

formally recognized and who can enjoy special rights including limited priority access to some land and natural resources, the growing Telengit-

consciousness in the region is of considerable importance for this project. At the moment there are a few obshchinas of KMN registered in the

district, and territories belonging to two communities (Kurai and Beltyr) have been declared (on the local level) Territories of Traditional Nature

Use , a unique form of protected area that only recognized KMN are entitled to establish.

The Tyvans residing in Mngn-Taiga do not have the status as indigenous small-numbered peoples. However, Mngn-Taiga (as well as Kosh

Agach) is officially recognized as a raion Krainego Severa (district of the Far North). This designation is determined on the basis of extreme

ecological and climatic conditions and difficulty of access, leading to inordinate expense in production and in providing for the basic needs of the

population. If a region has Far Northern status, all of its inhabitants are entitled to certain privileges: higher salaries in the state sector, lower

retirement age, and the so-called severnyi zavoz (northern delivery), i.e. priority delivery of fuel, coal and basic necessities.

It is important to note that in terms of religion or worldview most of the Altaian-Telegits declare themselves as following their own Altaian faith.

This faith, or rather worldview, is sometimes called Altai jang and it is based on worship of land and nature. The main non-human agent is

Altaidyng eezi. This notion, which is most often translated into Russian and English as master spirit of Altai, indicates that the Telengits consider

the nature as a living agent. Altai is alive and wild animals are considered as his property. Altai can give a person an animal if asked properly and a

person should take whatever is offered to him. Overhunting, cutting trees on mountain slopes, polluting water are treated as sin (kinchek) that can

bring punishment not only to the person involved by also to his relatives and descendants.

Still, although on the level of declarations the worship and respect for Altai is relevant (every single respondent said that nature should be protected

and respected), this does not mean that nowadays Telengits always do treat nature with respect according to standards of ecological organizations.

Still, there is a strong awareness that humans are not masters but part or even subordinates to nature. This consciousness should be strengthened

through various activities supporting Altaian culture that would bring back respect for old customs and crafts (see recommendations).

10

In Mngn-Taiga , more than half of respondents listed Buddhism as their

religious affiliation (17 of 30); five said they were atheist, while the

remainder did not respond to the question concretely. However, there is no

perceived contradiction between simultaneously holding Buddhist beliefs

(or atheistic leanings) and beliefs associated with Tyvans shamanist (or

more accurately, animist) traditions. This becomes most evident in peoples

beliefs in spirit masters of places, and the importance of respecting spirit

masters and paying homage to them when hunting. In this sense, the

worldview of many Tyvans in Mngn-Taiga is similar to Altai jang of the

Altaians.

Place of Chaga bairam ritual next to Kurkure village

Who is a hunter and who is a poacher?

Tyva

In the Mngn-Taiga sample, of 17 respondents who said that they hunt, six said they were legally registered to hunt (i.e., they have a hunting card

- okhotnichii bilet). Of them, five have permits for their guns, and only two currently have the required licenses to hunt particular species. In other

words, the majority of them are technically hunting illegally therefore they are, by law, poachers. However, the emic (i.e., as understood by the local

population) definitions of poaching and proper hunting have nothing to do with legal permissions or the lack of them. For a number of reasons

(bureaucratic hassles, expense, inconvenience), the majority of those who hunt do not have hunting cards or registered guns, yet they feel that

hunting is their birthright and that their hunting activities do not constitute poaching. Rather, poaching and proper hunting are differentiated along

the lines of the quantity and types (male or female; adult or juvenile) of animals taken, hunting methods, purpose for hunting, and whether certain

customs are observed or not. In response to survey item #40, which asked respondents to complete the sentence, A poacher is. . ., not a single

person in the Mngn-Taiga sample mentioned anything about not having the necessary permits and licenses. Typical responses were:

A poacher is not a real hunter. A real hunter will only kill one or two animals, even if he sees 10. A poacher will try to take them all.

Poachers are those who hunt to sell animal parts; those who hunt for trophy.

Poachers hunt during birthing season and shoot pregnant females.

Poachers dont take care about nature; they dont know how to protect nature.

A poacher is a greedy person, a person who still wants more even though his stomach is ready to split, who is blinded to anything except what he

wants to take for himself. (Tyvan: Chazyi khoptak, ishti charlyr chetken, karaa kozulbes kizhi dir.)

11

A poacher is a person who only thinks about his own desires and wishes, who goes out to hunt and comes back in the same day and who doesnt

think about the future or about leaving something for his children.

In response to item #42, which asked people to describe a real (Rus. nastoiashchii, Tyv. yozulug) hunter, again responses did not include mention

of licenses or permits. Rather they focused on respect for animals and for spirit masters; on having proper knowledge to be a good hunter; and on

following traditional customs. (Some of the following are composite quotes.)

A real hunter hunts to feed his family. He respects the cher eezi (spirit master of the place). He respects all animals, no matter what even wolves,

because wolves themselves are great hunters. When you talk about a wild animal, youre talking about the lands wild animals. (Tyv. Ang deer,

cherning angy.)

Real hunters know how to tell the difference between types of animals (male, female; adult, juvenile). They know tracks and know how to track

animals. They know the best seasons to hunt, and only hunt during those times.

A real hunter knows and follows the old hunting customs and traditions. He doesnt kill many animals and he isnt greedy (Tyv: khoptaktanmas).

A real hunter takes care about the old Tyvan hunting traditions. He first asks for permission to hunt from the spirit master, and he doesnt take

more than he needs.

A real hunter hunts only when his lifes needs demand it, to feed his family. He pays homage (chalbaraash) to the spirit master of the place, and

only asks the spirit master for what he needs, not more. Also, a real hunter must wipe out all wolves even if there are absolutely no more left, a

real hunter hates wolves.

Perhaps most interesting were responses to survey item #41, which asked respondents what type of hunting and hunter represented the greatest

threat to wild animal populations and to nature in general. Several respondents noted that it is precisely those who have all necessary permissions

(including inspectors, border guards, and police) who are the real poachers and pose the greatest threat to wild animals. One local hunter said that

the greatest threat comes from People who have the money to buy expensive automatic rifles, but dont know how to hunt. They drink when they go

hunting. Some local people do this, some dargalar (bosses, officials, authorities). Also, they dont distinguish between male and female, dont take

the season into account. They shoot indiscriminately. Another respondent reinforced this sentiment, noting, Now that theyve started selling these

expensive large-caliber guns with dalnomery (laser-guided distance measuring scopes), its people with licenses for these guns who are the greatest

threat. Another put it more succinctly: Big-whigs who are out for fun and sport (Tyv: Oyun-khg bodaar darga-boshkalar.)

Other respondents focused on certain ways and times of hunting as representing the greatest threat:

People who trap carelessly, without first taking the time to check out where theres likely to be large male marmots, because then their traps will

trap young ones as well. Those who hunt at night using high-powered lamps (chyrydar). People who hunt all in one day, without taking an extra day

or two just to check out where the biggest adult marmots are.

Those who overhunt, who hunt during birthing season. People should hunt only in the autumn.

12

Finally, some people mentioned that the greatest threat to the wild animal population is young people, while others mentioned carelessness with fire.

Young people are the greatest threat because they dont think before they shoot; they dont know or respect our hunting customs, said one

respondent. According to another respondent, the greatest threat comes from Those who cut trees, burn the grass. They cause fires. Also, young

people from the village.

If WWF hopes to have good cooperation and working relations with the local people, then these emic understandings of poaching, proper hunting,

and threat must be taken seriously. These responses suggest a number of possible directions for future WWF activities, including educational

activities for young people; monitoring activities to be intensified during certain seasons; changes in licensing laws and practices, particularly re-

establishing a local representative of the hunting directorate who could issue licenses and register guns locally, thereby making it easier for locals to

do so. According to locals, when the promkhoz was active, the promkhoz director used to sell licenses (mostly for marmot; other licenses were so

expensive that no one could afford them) and issue hunting cards. However, now people have to go to Kyzyl to get okhotnichii bilety, to register

guns, and to get licenses to hunt certain species. The trip from Mugur-Aksy to Kyzyl takes 8-10 hours each way and costs about 1000 rubles each

way, not including food. People then have to live in Kyzyl while permits are being processed, which can be a lengthy process, or go back home to

wait and make yet another expensive and time-consuming trip to Kyzyl to pick up their permits. Even if they were to do so, there is no guarantee

that they would be able to get the licenses they want to hunt specific species. Even residents of Kyzyl have trouble getting such licenses. In

reference to licenses to shoot maral, one Kyzyl resident said, They issue how many licenses? I dont know, but theyre all snatched up by the

dargalar (big bosses) before anyone else gets a chance. What are we supposed to do? These problems suggest that work needs to be done to revise

the permit granting procedures, establish priority hunting rights for local residents, and devolve control over the issuing of permits to the local level.

Altai

At the moment the organisation of hunting is under reform in the Republic of Altai. A few years ago, as part of centralisation policies, the control of

hunting was handed over to Barnaul (capital of Altaiskii Krai), but at the moment it is in the processes of being returned to the Republic and the

structural reform follows. In 2006 local hunters formed an association (okhotobshchestvo) - or rather re-established it, as such an organisation

existed in changing forms in the Soviet times and then up to the mid-1990s. According to its head in Kosh Agach, Nikolai Shonkhorov this

organisation has officially c. 160 members in the district and this is the number of people who can hunt legally if they get an appropriate license and

permission for guns. At the moment the association has a right to issue hunter cards (okhotnichii bilet) and they keep the catalogue of hunters. The

official state organisation responsible for hunting (okhotnadzor) is at the moment in charge of issuing hunting licenses and it also keeps an overview

of the hunting cards. The relations between okhotnadzor and okhotbshchestvo are not clear at the moment everything is being re-organised. At the

moment there is only one employee of the okhotzadzor in Kosh Agach and he seems to be mostly absent from his office. Okhotobshchestvo hopes to

regulate in future all hunting activities, including issuing licenses and selling guns and other hunting equipment, but the reform is still in process.

One can say that at the moment situation is quite unclear and local people are not well informed about the ongoing changes.

13

Roughly half of the interviews and surveys with people who hunt were conducted with hunters who have hunting cards (12 survey forms), hence

with the members of the hunting association. Out of them, 9 had permits for guns. At the time of survey none of them hold a license for a particular

animal, but the research was conducted outside of the hunting season. However, the longer conversations revealed that this division into people

with documents and people without documents seems to be of great importance neither with regard to attitudes to hunting nor with regard to

constellation of hunting groups. In Kosh Agach people usually hunt in groups of 3-4 people and those groups are mostly formed regardless of

hunting permits. Rather, people come together according to friendship or kinship lines. Most hunters holding official permits declare that they can

well understand their fellow people if they do not apply for one. This is a long bureaucratic hassle followed by a long wait for a gun, which is the

main purpose of applying for hunting card anyway. Getting a hunters card is only the first step, as the real trouble begins when people want to get a

gun. For the first 5 years a hunter should use only smoothbore gun (gladkostvolnoe oruzhe), from which one could shoot only up to 60-80 meters.

Only then a license for grooved guns (nareznoe oruzhe) can be issued. Getting any kind of gun requires undergoing medical examination, passing

relevant tests and holding a clear criminal record. It requires a trip to the capital (over 400km) or even to Barnaul (over 700km), ordering a special

metal container for guns and a yearly re-registration. None of the herders living in camps interviewed hold a hunting card as they claimed that they

do not have time and funds to undergo this procedure.

Getting license for a particular animal is seen also as a hassle. Theoretically one can get it in Kosh Agach, which obviously involves first a long trip

to the district centre. Hunters complained that the issuing office is frequently closed, but even if it is open one has to be given a relevant license, go

to the bank, queue to pay his fee, get back to the office (which is often closed by the time one is back) and get the paper. After hunting the license

has to be brought back within a few days, otherwise hunter would be fined.

Even more importantly, the very logic of license goes against Altaian traditional perception on hunting. As it was said above, wild animals are seen

as belonging to Altaidyng eezi, who could give a hunter a prey or refuse to do so. A hunter should not be choosy - he should just take whatever he is

given. A license on the other hand is given for a particular animal. Although registered hunters declared at first that they are trying to get a license,

all of them admitted that they often hunt any animal they meet regardless of the license they hold. Often a license is regarded as a kind of pass to

the forest with all relevant documents (hunting card, permission for gun, license) one can legally go to the forest or to the mountains without fear

of being caught.

This is precisely how the hunters without hunting cards see the role of all kinds of hunting documents. They claim that often the hunting groups are

constituted both from registered as well as unregistered hunters if they are spotted by rangers at least one of them have relevant papers. Moreover,

the license is filled in only if the person is seen by strangers or controlling organs killing the animal. If animal was killed without witnesses it is

taken home and the same license is used again.

Interestingly, in research area 1 some unregistered hunters reacted very negatively to the idea of legalization of hunting for all indigenous

inhabitants. Here is a quotation from an interview with a person who himself hunts without registration:

14

If you legalised hunting among local people, they would openly walk around with guns. For example, one leaves the village one is

allowed to take a gun with him. And then they would walk with this gun day and night. And now this is like this he goes hunting on

purpose and while he goes he hides his gun and tries not to be seen. He kills an animal, quickly takes it home and again he hides

himself. And if he was legalized, he would be everyday in the forest with the gun! Legalisation of local hunters is like sentencing the

animals to death.

The same person pointed out that local people usually do not have money necessary for purchase of technologically advanced guns. Therefore, even

if they wanted they could not kill many animals their guns are not good enough and the price of ammunition makes them to shoot rarely but

precisely.

However, in the research area 3 the reaction to eventual legalization of local hunting was opposite: all respondents in Kurkure agreed that hunting

rights (and gun permissions) should be given to all local people. Still as local people they mean people from Kurkure and as one of important threats

to wildlife (apart from strangers and helicopter hunts) they declared people from research area 1.

The answers to item #40 (A poacher is) do not differ significantly between registered and unregistered hunters. However, in contrast to Tyva,

there were answers that referred to legality of hunting. It can be said that especially in the research area 1 local people are well aware of the official

representation of poacher as someone who hunts without permission which implies that he is at the same time a threat to wildlife. In many cases it

was clear that people do not feel comfortable with this term in several cases Halemba was explicitly asked not to use the term poacher at all and

hence people refused to answer to 40#. Instead, they willingly answered to question 41# (who is the real threat to the animals).

The answers given to #40 could be subdivided into following groups:

a. Answers given by unregistered hunters, who simply stated:

Poacher this is me

Poacher is first of all a human being

Poacher is a human being

Poachers are just people like you and me

We are poachers

Similar answers (Poachers are first of all human beings) Halemba received also from a couple of registered hunters, who underlined that they

understand those of their fellow villagers who do not have cards but hunt.

b. Answers given by some registered hunters exclusively in area 1. Those people seem to internalize the officially promoted image of a

poacher

Poacher burns forests (lesopodzhigatel), he is a destroyer, he does not have any human thoughts, he does not think about kids.

Poachers is the one who hunts without license, without anything, he is the enemy of nature

Poacher is a thief, a killer, a destroyer of descendants

c. Answers which refer to particular behaviour and were similar to the ones given in Mngn-Taiga.

15

Poacher is the one who kills without measure

Poachers are those who hunt without measure, they kill everything they see. But we do not have such people here in Argyt

It has to be noted however, that the attitudes to labelling someone poacher cannot be fully discerned on the basis of this simple answers. For

example, people who gave answers b. made clear in other parts of the conversation that they do not think there are many poachers locally. This is

true that local people hunt without license, but they are not really threatening to the animal population.

One registered hunter, who admitted that he hunts without license answered to #40 in the following way:

Poacher is obviously a hooligan. But you have to look closely at him. I am hunting for food, for meat! And other people here as well.

They are not hooligans

Instead, the image of real poacher appeared in the answers to question 41#, where we asked about the kinds of hunting which are most dangerous

to wildlife. Here the issue of legality appeared only in one case of registered hunter, who expressed earlier his strong feelings against poachers. He

declared that the most dangerous are uninstructed people who do not respect and break the law.

Most of the respondents declared that most dangerous for wildlife are priezhie (strangers) or chinovniki (officials). In Argyt valley (Kurkure), all the

respondents stated that most dangerous for wildlife is helicopter hunting, which they claim to witness themselves.

This is the outsiders (priezhie) who bring damage, our people do not do it. They do not look carefully, just shoot everything.

Officials who shoot anything they see

Also the image of ranger appeared in the responses to this question:

The biggest damage is done by rangers.

In sum: in Altai few unregistered hunters see themselves as poachers. Those who do use this designation for themselves usually live in bigger

villages close to the main road. Still, they use it because they are aware that this designation is officially used to describe their activities. Most of the

unregistered hunters see themselves as harmless to animal population. They see their activity as moderate and harmless, they think that they do not

take more than they need, that the environment can provide and sustain, and that they do not hunt for material gain. As most dangerous for animal

population are seen strangers, people in position of power (especially in the army) as well as members of controlling organs (police, rangers, border

guards).

Reasons for hunting and morally appropriate hunting:

There is a significant difference in the attitudes to hunting between Altai and Tyva. Some of these differences may well be related to the wild game

populations in the two areas. The Kosh-Agach area is more heavily forested and recognized as having more species of game animals as well as

having higher populations of most species. Hunting has probably historically been a more important activity both culturally and economically than

in the Mngn-Taiga district of Tyva.

16

Tyva

In Tyva, illegal hunting to feed ones family is nearly universally accepted. Hunting to sell parts or for trophy is not acceptable. While ten

respondents said that they hunt because it is interesting, none mentioned the adrenaline rush, or the thrill of the hunt. One respondent noted that he

thinks hunting for the thrill of it has declined noticeably over the past years. No one discussed hunting as an important source of income, especially

not now, since theyve cracked down so hard on marmot skins and since theyve firmed up the border with Mongolia. In keeping with the general

tone of respect for official nature protection measures, the largest number of Mngn-Taiga residents noted that they think local people respect

legal hunting and not illegal hunting, and that those who hunt illegally need to hide it from others. The survey data do not give a clear picture as to

how many people in Mngn-Taiga are believed to hunt illegally. Some respondents believe that almost all adult males do, while others said very

few do. However, if we triangulate the data in question 32 with the survey sample numbers (17 hunters, only two with full permissions), and with

interview and observation data, it appears that those who suggest that a large proportion of the adult male population hunts are probably correct.

Altai

Respondents opinions on numbers of hunters and their perceptions of reason for hunting have been fairly consistent within the three research areas

in the Altai. On the basis of survey data and interviews the situation is locally perceived as follows:

Research area 1:

Kurai and Kyzyl Tash: every third-fourth man hunts at least once a year. C. 15 people hunt regularly and for 3-4 families hunting is a significant

source of income. All people interviewed declared that they hunt out of interest but also for adrenaline, for the thrill of it, and that this is just in

their blood.

Chibit: this is the hotspot of hunting. Only 10 people there are registered hunters and the same number has registered guns, but according to local

clan leaders (jaisan) the number of hunters is probably c. 100, which makes every second men in the village a hunter. Probably for 10-15 families

illegal hunting is one of the main sources of income. Most of the people declared that they hunt for adrenaline but also for meat not because of

lack of income but because they like wild game. No one declared that he personally hunts for sale, but people declared that it is the main reason for

several of their fellow villagers and that they would probably hunt less if they had other sources of income.

Research area 2: Every eight men between 15 and 55 years of age hunts. Half of them have hunting cards. Border guards posts are close to these

villages and valleys, so the illegal hunting among local people is limited.

The most often given reason for hunting was that it is in peoples blood. In case of wolf-hunters this is seen as obligation towards herders.

Research area 3: In Kurkure it can be safely assumed that almost every man between 15 and 55 years of age hunts, almost all without hunting cards.

In Dzhazator the majority of the population is Kazakhs, but most of the hunters are Altaian. There is no reliable data on this village, but it is

definitely an important trading point for hunting products.

17

Kurkure village

In Kurkure the reason for hunting given was tradition, but also hazard. In this

village Halemba managed to talk to some people who indirectly admitted that

they hunt for sale but they were also ready to give up this type of hunting if they

had other sources of income. Interestingly, some respondents admitted that they

once or twice took part as guides in legal and illegal trophy hunting trips for

strangers, including helicopter hunts. However, they also claimed that they

refused to be further involved in such activities as they do not approve on the way

the hunting is undertaken during such trips.

There is among the local hunters an image of hunting that is morally appropriate. This image should be strengthened and maybe modified but not

fought against. Of course, people admit that they sometimes break the rules themselves, but they do hold them in general as valid and could be quite

easily convinced to stick to them, if the social control is strengthened. The most important features of such hunting are as follows:

One does not hunt more than one needs for his/her own consumption. This means e.g. that out of a group of 10 mountain goats one should not

take more than 1-2 animals for a group of 3-4 hunters. Overhunting is seen as a sin (kinchek) that is transferred from a hunter to his children.

Hunting should be done not more than 3-4 times a year.

All parts of the animals should be used. Trophy hunting and leaving the meat behind is generally frowned upon.

The place should be cleaned after killing an animal. No animal leftovers are to be left at the scene.

Hunting in spring is forbidden as well as killing very young animals. Hunter should preferably kill adult males only.

It is forbidden to kill the first animal in the herd i.e. for example a leader of ibex.

If hunting with traps, they all have to be removed at the latest in March. Leaving traps behind is frowned upon. Between February (after Chaga

bairam) and June hunting should not take place.

Meat should be shared among all the hunters in equal parts regardless of who killed the animal. The youngest hunter divides the meat into as

many parts as there are hunters. Then another decides, without looking, which pile is going to which hunter.

Female hunters are very rare. They are more present in the Ulagan district.

18

Telengits emphasize that they use all parts of hunted animals as much as

possible. Here a car part usually manufactured out of plastic was carved

out of ibex horn.

Our data confirm that the cultural reasons for hunting far outweigh economic considerations, and in all research areas of the study people agreed

that hunting would continue even if they had much more money. This is consistent with other literature on the topic. For example, a study of

poaching in Tanzanias Western Serengeti determined that poaching households tend to be wealthier than non-poaching households, and that the

decision to poach may be more an issue of opportunity time rather than household wealth (Knapp 2007:195). This suggests that employment

generation schemes will be more effective way of reducing poaching than pure wealth generation mechanisms. However, alternative sources of

income could reduce the amount of hunting, especially if they are supplemented with community-based control systems (see recommendations).

The idea of hunting tourism (hunting for trophy) was rejected by almost all of the respondents in the Altai sample, but was more acceptable to the

respondents in the Tyvan sample, where half of the respondents said they could support hunting tourism if it were carefully regulated. Danil

Khertek, the village head of Kyzyl Khaia, noted that trophy hunting could cause some resentment among locals, but suggested that if we work at

explaining what we can do with the money -- build a kindergarten for our little kids, or buy computers for the school, or use the money to fix up the

old cabin at Ala-Taiga arzhaan then people will agree to it. However, Dadar-ool Shagdyrovich Irgit, inspector for Ubsunurskaia Kotlovina Nature

reserve in Mogen-Buren area, said that the wild animal populations in the area were not large enough to support hunting tourism.

19

Attitudes to animals

The table below summaries the most important information regarding the local perception of wild animals.

Argali

,

Altai

All respondents agree that they should be protected. Most of the local people claim that they do not hunt them, but they

do have an opinion on the taste of their meat - although some people like it, for most of them it is too dry. Local people

do not hunt argali for trophies even the ones who do hunt for money. Moreover (and much more important) the main

inhabitancy areas for argali are high plateaus that are located within the border area. There are border guards stationed at

several posts (zastava). In order to hunt argali one has to either pass one of those or try to go round it, risking being

caught. Local people therefore say that as a rule they do not hunt argali. In their perception the most avid argali hunters

are 1. border guards themselves 2. officials and their friends, who hunt them from helicopters, as argali graze on the high

altitude plateaus.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga , argali seems to be more of a species to hunt. The meat is considered not only delicious but medicinal

because of the izig ot (literally, hot grass) that they eat in their high, dry habitat. The population is considered rather

stable, but declining. One respondent who had participated in an official count in 2002 said there had been about 100 in

the area around Mugur-Aksy then, and estimates that there are about 80 now. Respondents said that argali generally

live in Mongolia and Altai, and only cross the border over into Tyva in November or December, stay for a month or

two, and then cross back.

Snow leopard

,

Altai

All people agree that this animal should be protected. Still, Halemba met very few people (only two, both hunting

illegally) who claimed that they would restrain from shooting snow leopard if they see it accidentally while hunting.

Most of the hunters, legal and illegal said that they could not stop themselves from shooting killing a rare animal is a

great feat for a hunter. There are however very few people who premeditatedly hunt snow leopard (two respondents

admitted it). It is usually done with traps.

Also, almost everyone agreed that snow leopard should be killed if s/he attacks the herds. It does not happen very often,

and the animals that attack herds are usually old. Most of the people say that snow leopard just takes one animal and

does not hurt other ones. Only in Kokoru (research area 2) people described a case when snow leopard attacked a herd

of horses. He killed one of them but he also hurt several others with his claws. People believe that in this way he was

preparing them to be his pray in future weakened by wounds they would have been an easy catch.

There is a mixed reaction to the snow leopard settling next to the shepherds camp. Most of the people say it is extremely

improbable as the animal prefers to stay high in the mountains. Those who admit that it can happen can be divided into

20

two groups. A minority of respondents (c. 20%) claimed that this would be a good sign for the camp and that they would

not try to kill such an animal. They have also claimed that such a snow leopard would not try to get the domestic animals

of its human neighbor. Still c. 80 % said that they would try to kill such a snow leopard as they would be afraid of his

attacks on animals. Very few people think that snow leopard could attack a man at all.

Tyva

Views in Mngn-Taiga are similar. Everyone agrees that they

need to be protected because they are universally recognized as

one of the rarest and most beautiful animals in the world. No one

said they would ever go out with the intention of hunting them,

and in fact no one in the sample said they would shoot one unless

they felt it presented a threat to their livestock. Just prior to this

research in Mngn-Taiga, one private herder suffered a massive

slaughter of 80 sheep by a snow-leopard. The snow-leopard

entered the enclosed corral from the roof and killed almost all the

sheep in the corral (see photo). While this herder was devastated

by the event, and is hoping for some form of compensation from

the government or from WWF, he still responded that snow-

leopards need to be protected. Such attacks are rare the

zapovednik inspector said that he can recall three, one in the late

1980s, one in the late 1990s, and this one. The head of administration said he only remembered two one about 10

years ago, and this one. All mentioned that snow leopards kill several yaks every year, but this is to be expected.

Musk deer

Altai

According to hunters, the population of this animal has dropped significantly in the late 1990s. They see the fault of

local people in this in the late 1990s the price for the musk gland was high and it was easy to sell. People hunt musk

deer with traps and if a female is caught they just leave the body to rot. Although hunters admitted that local people do

it, they view such practices very negatively.

The hotspot for hunting musk deer is the village of Chibit and probably a bigger settlement of Aktash located nearby.

Aktash was pointed out as the place when illegal trade in musk gland is taking place.

At the moment the population of musk deer is, in perception of local people, growing. No licenses for musk deer are

issued at the moment and people claim that illegal trade has also significantly dropped.

Tyva

According to one hunter in Mngn-Taiga , musk deer should be hunted when there is a full moon, because that is when

the musk glands are fullest. There is no substantial musk deer hunting in this region.

21

Wild boar

Altai

According to local perception, the population of this animal is growing, especially in recent 2-3 years in research area 1.

Wild boar is perceived as an aggressive animal, destroying meadows which are kept for hay-making and even killing

young elks. Some of the respondents would like to eliminate wild boar altogether.

Tyva

Mngn-Taiga : wild boar are rarely seen and are particularly difficult to hunt and kill, so few people actively hunt

them. For these reasons, they dont need special protection beyond regular hunting restrictions. Their population seems

to change from year to year, but appears overall to be stable.

Bear

,

Altai

The population of this animal is seen as stable. People hunt it for fat, gall bladder (zhelch) and skin. They are also

known to attack domestic animals and then they are hunted.

Tyva

Mngn-Taiga respondents mentioned that there are very few if any bears around.

Wolf

Altai

This animal is rarely talked about using its own name br. Instead, it is called different names, such as e.g. kush-ijit

(lit. bird-dog). People are respectful towards wolves as they do not want to draw their attention. All of the hunters agree

that the population of wolves is growing and that they are very dangerous for herds. They agree that wolves should be

hunted by specialized hunters and preferably eliminated altogether.

The only exception to this general trend of seeing wolf as an enemy that should be removed with any means was voiced

in the Kokoru village. There, a group of well-organised (and registered) wolf-hunters operates. Their said that wolves

should be hunted exactly in the way as other animals are for example, one should kill neither pregnant females nor

puppies.

The premiums for killing wolves depend on the district (between 3000 and 5000) and are seen by hunters as too low.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, virtually all people said that wolves should be actively hunted. They are perceived as pests and a

threat to livestock that needs to be eliminated. The population is perceived as growing. People feel they should shoot

wolves on sight, with no consideration for season. The meat and skins are not of much value, but the government pays a

premium of 4000 rubles for each wolf killed, creating an economic incentive for hunting them.

Mountain goat - ibex

Teke, j;

,

Altai

This animal is seen as not endangered. Apart from Kurai village (where many people prefer hunting elk and do not go

higher into the mountains where teke usually resides), this is the most popular animal for what people consider proper

hunting (see above).

22

The local hunter who killed this ibex does not have a hunting

license, and his gun is not legally registered. Such hunting is

illegal, but locals feel that they should have priority hunting

rights and greater control over wildlife resources. (Mngn-

Taiga District, Republic of Tyva, 2008. Photo: B. Donahoe)

Tyva

Likewise in Mngn-Taiga, the population of this animal is

seen as stable or growing. People feel there are plenty of

them, and several people said they saw no reason for special

measures to protect them, beyond the standard hunting

restrictions of season, etc. The meat is considered to have

medicinal properties because of the izig ot (literally, hot

grass) that they eat in their high, dry, rocky habitat.

Sable

K,

Altai

They are hunted with traps in research areas 1 and 3. There are no concerns with regard to decline of population.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, people said that there are no sable to speak of.

Roe deer

Altai

They are rarely hunted on purpose, i.e. a hunter rarely sets off with an aim to get a roe deer. Rather, they are just killed

when they are seen on the way.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, one hunter said that there used to be a lot of deer, but the population seems to have plummeted in

recent years. He suggests that they may have outmigrated en masse for some unknown reason. They should be

protected. Best to hunt in May because the hair in their ears is long and they cant hear.

Red Deer

,

Altai

Hunted in autumn (for meat) and in May (for panty). In Chibit people prepare salt traps for them (salantsy). The most

hunted animal in research area 1.

Tyva

As most of Mngn-Taiga is not forested, there are very few red deer. Hunters value them and will shoot them if they

come across them, but they generally do not go out looking for them, as they are so rare.

23

Marmot

Altai

Those animals have been very widespread in the steppes until the mid-1990s. People claim that they were overhunted in

the late 1990. At the moment people notice that the population of marmot I going down. Moreover, c. 5 years ago, when

the price for marmot fur was high, they were poisoned in order to get large number of fur fast. Altaians claim that this

was done almost exclusively by Kazakhs Altaians like the meat too much to spoil it in this way. Presently, the price for

marmot fur felt down and they are hunted exclusively for meat which is believed to have medicinal properties. Hunting

marmot is not seen as proper hunting. There are people (also women and children) who hunt marmot but they do not

consider themselves hunters. This is very much widespread attitude in research area 2.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, marmot is the most important species to hunt for cultural as well as for economic reasons. The meat

and fat are considered medicinal, and the oil that can be obtained by hanging the fat and letting it drip is both valuable

and important. It can fetch 1000 rubles/liter (25 euro) locally, and as much as 3000 rubles/liter in Kyzyl. The skins used

to also be valuable, but since marmots have been placed in the Red Book and hunting is prohibited and somewhat strictly

enforced, and the border between Mongolia and Tyva has become stricter, the market for marmot skins has dried up.

People hunt them with traps, or simply drive a bit off road and wait for them to come out of their burrows and shoot

them. The population declined precipitously in the 1990s (the time of

crisis), as people hunted them indiscriminately out of need for meat and

money.

Hunting seems to have declined somewhat from that peak period, but still

most respondents said the population is low and needs special protection.

Just outside the village of Mugur-Aksy in Mngn-Taiga, a large statue

depicting two marmots has been erected (see photo), and locally they have

declared a groundhog day, both activities designed to engender pride in

the marmots and an awareness of their situation.

Fish

Altai

Fishing is generally seen as a leisure activity. There is no difference between attitude towards protected and other

kinds of fish.

Tyva

The main fish in the area is grayling (Rus. kharius, Tyv. kadyrgy). People fish for them in lakes under the ice with nets

in late winter, as well as in warmer weather. One person mentioned that the quota of grayling in Khindiktig Khol

(Mngn-Taiga) is never reached, therefore there is the danger of overpopulation in that lake. Some fishermen from

Mngn-Taiga cross over into the Altai Zapovednik to fish in lakes there.

24

Birds

Altai

No significant hunting, apart from ducks. Still, people would shoot ular if they see it. There was a peak of hunting

falcon for sale in the 1990s, but apparently there are no buyers anymore. According to respondents Kazakh people

were also involved in catching and trading falcon. The population of birds is considered healthy.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, the falcon population seems to be healthy. People here

dont hunt them generally (although some said there might be a few

younger men in Mgen-Bren who hunt them). One hunter showed

Donahoe a rather elaborate snare used for catching falcons (see photo). It

is small frame made of string and flexible wire, with several small snares

and a long dangling string with a large, 4-sided hook attached. The snare

is hidden under the wings of a live pigeon. A rock is also tied to the

dangling string to prevent the pigeon from flying high. Then the pigeon is

released. The hawk catches the pigeon in flight, and in its efforts to claw

through the feathers to get to meat, its claw gets caught in one of the

snares built into the trap (there are several). As it cant lift the pigeon-

with-rock very high, the string with the large hook drags along the ground

until it catches onto some grass or a bush. Then the hawk can be reeled in

by the string. One respondent said that they can get 30,000 rubles for one.

Also in Mngn-Taiga some people hunt ular. The perception is that the

population is healthy, and that their meat has medicinal qualities.

Attitudes to nature protection areas

Altai

Someone wants to buy this territory and make a nature reserve. They will push us out of here and they will hunt here, the animals will be gone.

This quotation from an interview with a herder in Argut valley (Altai) can be considered representative of the attitude towards nature protection

territories in research area 3 in Altai. The general tendency is that the further away from an existing or planned protected areas people live, the more

acceptance or even support they have for its existence. Especially in the villages next to the main road there are quite a few people who agree that

strict control is the only way to reconcile the urge among the local people to hunt and the need to protect the animals. However, even they are afraid

25

that actually the most dangerous hunters are the officials and guards who have access to animals anyway: whether they live on the protected

territory or not.

In the areas close to existing or planned nature protected territories, especially nature reserves (clusters of the planned Sailukemski zapovednik),

people are generally against the introduction of protected areas. Obviously they are scared of being removed from their land (i.e., that herders

camps will be relocated and they will be prevented from using those areas as pasturage). Still, this is not the only problem they see. Especially in the

places close to existing protected areas such as Ukok or Shavlinski zakaznik, the term nature reserve (zapovednik) is often interpreted and

understood by local people as a hunting ground (okhotougodie) reserved only for officials or even private owners. The situation is especially dire in

the Argut valley, in the village of Kurkure and surrounding herders camps, where the equation nature reserve = private hunting ground seems

to be firmly established among local people. It must be said however, that, given the fact that some of them have experienced and seen the outcomes

of helicopter hunts organized in Shavlinski zakaznik, their interpretation of the situation cannot be seen as groundless or dismissed as a

misunderstanding. For example, Halemba saw personally addressed letters that inhabitants of Kurkure received from an entrepreneur from Ust

Koksa district, in the wake of elections for the head of the Kosh Agach district

3

that took place on the 3

rd

March 2008. In his letter he asked people

to give their support to Auelkhan Dzhatkambaev (who was the head of the region at that time). In exchange he promised to open a company Arkyt

on this territory and promised people investments in the region. Fortunately, inhabitants of Argut knew that he is an owner of tourist enterprise

organizing commercial hunting some of the local people were on his hunting trips as guides before (including helicopters hunts). They

disapproved of this and were afraid that the territory would turn into a ground for commercial hunting if this entrepreneur opens his company. Argut

inhabitants voted overwhelmingly for Dzhatkambaevs opponent, Leonid Efimov, who has won the election. Interestingly though, people think that

now, although the entrepreneur cannot open his company in Argut any more, he is nevertheless behind the creation of the planned nature reserve on

the same territory. It is believed that he has made a deal with some people in power in Novosibirsk, who decided to create a nature reserve in

order to organise hunting trips to Argut. For the people of Kurkure private company and nature reserve are understood as equivalents they see

both of them as limiting the local peoples access to the land, as being run by outsiders and as means of disempowering local population.

If the nature reserve or any kind of nature protection territory is to be established there in future, there is a definite need for explaining the situation

to the local people. At the moment they are not going to believe that any nature protection initiative would benefit either the population of wild

animals or their interests. They can recount numerous stories about officials and hunting tourists coming to Shavlinski zakaznik to hunt (both with or

without permissions) using helicopters, high-quality weapons and hunting everything that moves. If any herders camps are to be removed because

of the establishment of a new nature protection territory, this would definitely estrange local people, which should definitely be avoided. Moreover,

we suggest that it has to be very carefully considered who is to work in the reserve itself. Ideally, the protection of the territory should be given to

people from Kurkure and the headquarters of the nature protection territory should be located in this village. Still, the agreements and negotiations

concerning the mode and extent of nature protection should be conducted not with individual inhabitants but with an association of local people

which hopefully will be soon established (see recommendations).

3

Shavlinski zakaznik is situated mostly on the territory of the district of Kosh Agach but is also easily accessible from districts of Ulagan, Ongudai and Ust Koksa.

26

In the areas further away from protected territories the attitude towards nature protection is more positive. The most important concern the

respondents voice is the question of rangers they should be chosen from locally respected people. Some older respondents referred to the Soviet

practice of neshtatnye egera (non-salaried rangers). These were local herders, who had control rights on the territory in the vicinity of their camps.

Those who remember this system claim that it was very effective.

Tyva

In Mngn-Taiga, the acceptance of OOPTs is higher than in the Altai. 25 of 27 respondents agreed that the creation of OOPTs is the best way to

protect the animals and 20 respondents strongly agreed that more OOPTs should be created in the future (item #48). There are at least two factors

that help explain this: 1) the fact that there are fewer OOPTs in Mngn-Taiga than in Kosh-Agach (in fact, there is only the Mngn-Taiga

segment of the Ubsurnurskaia Kotlovina Nature Reserve); and 2) the fact that in Tyva generally there is still more respect for, faith in, and reliance

upon governmental agencies to deal with most problems. Residents of Altai have actively tried to take matters into their own hands by establishing

their own locally managed parks and protected areas, while residents of Mngn-Taiga see such activities as the exclusive domain of the state.

Nevertheless, as in the Altai case, those Mngn-Taiga residents living closer to the core zone of the nature reserve (i.e., those living in Kargy

sumon) were more likely to be critical of the nature reserve than those living in Mogen-Buren. In a meeting between district administration, nature

reserve officials, and the WWF representative, Aian Adai-oolovna Salchak, deputy head of district administration for economic affairs, noted that

the existence of the nature reserve restricts opportunities for economic development, notably animal husbandry (by making important pasture areas

off limits), tourism, and mining possibilities. This is resented by some locals and has caused conflicts between local residents and the nature reserve.

As one interviewee put it, We live there, we use that territory and we use the natural riches there, to pasture our animals. People also hunt there.

But if they turn it all into a zapovednik, we'll lose those opportunities, and we won't be able to live, because our lives depend on being able to use

that land. In this kozhuun (district), there's nothing else you can do but herd animals and hunt and fish. Other interviewees in Mugur-Aksy also