Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Intellectual Property and Innovation in The Knowledge-Based Economy

Uploaded by

yoolya23Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Intellectual Property and Innovation in The Knowledge-Based Economy

Uploaded by

yoolya23Copyright:

Available Formats

71

isuma

ABSTRACT Intellectual property rights (IPR) are institutional tools

that allow for the creation of markets to stimulate private initiatives

in intellectual creation. Basically, this amounts to restricting access

to knowledge by granting temporary exclusive rights to new

knowledge and thus enabling the inventor to set a price for its use.

Patents and copyrights are the main intellectual property rights used

to guarantee a degree of exclusivity to knowledge. Creating

monopolies on knowledge lead, however, to serious problems in the

allocation of economic resources. Patents and copyrights create

static distortions in resource allocation due to monopoly pricing and

may encourage socially wasteful expenditures by urging innovators

to invent around the patent. An overview of the economic and

policy issues surrounding intellectual property rights is presented,

with a particular focus on patents and copyrights. The main

economic challenge raised by the patent system is to keep a

balance between the social objective of ensuring efficient use of

knowledge, once it has been produced, and the objective of

providing ideal motivation to the private producer.

RSUM Les droits de proprit intellectuelle sont des outils

institutionnels permettant la cration de marchs en vue de

stimuler des initiatives prives en cration intellectuelle.

Fondamentalement, cela revient restreindre laccs au savoir en

octroyant des droits temporairement exclusifs sur un nouveau

savoir et donc en permettant linventeur dtablir le prix de son

utilisation. Les principaux droits utiliss pour garantir une certaine

exclusivit sur un savoir sont les brevets et les droits dauteur.

Toutefois, la cration de monopoles fonds sur le savoir suscite de

graves problmes dans lallocation des ressources conomiques.

Les brevets et les droits dauteur entranent des distorsions

statiques dans lallocation des ressources en raison de ltablis-

sement de prix de monopole et risquent dencourager un gaspillage

social des dpenses en amenant les innovateurs crer des

inventions tout en contournant les brevets. Le prsent article offre

un aperu des enjeux conomiques et politiques entourant les

droits de proprit intellectuelle, en sattachant plus parti-

culirement aux brevets et aux droits dauteur. Il se poursuit par une

analyse du principal problme conomique soulev par le systme

des brevets, soit ltablissement dun quilibre entre lobjectif social

dassurer une utilisation efcace du savoir, une fois quil a t cr,

et lobjectif consistant offrir une motivation idale aux producteurs

privs. (Traduction www.isuma.net)

BY DOMI NI QUE FORAY

Intellectual Property

and Innovation in the

Knowledge-Based

Economy

I

L

L

U

S

T

R

A

T

I

O

N

S

:

P

H

I

L

I

P

P

E

B

R

O

C

H

A

R

D

72 Spring Printemps 2002

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

T

wo categories of property rights have become

predominant as regards scientic and technological

knowledge: copyright and patents. Surprisingly,

these two categories have moved closer together over time.

Initially they were far apart, with copyrights covering liter-

ary and artistic property rights and patents covering indus-

trial property rights. But with the development of scientic

and technological knowledge these different rights have

often been applied to useful knowledge that enters the in-

dustrial sphere. The merging of patents and copyrights is

due essentially to the fact that copyright has conquered new

ground. By becoming the right most frequently used by the

information technology and culture and multimedia indus-

tries, copyright has entered the corporate world.

Patents: denitions

The patent, an instrument designed to protect innovators,

ensures them the right to a temporary monopoly on the

commercial exploitation of a device or method. It is a prop-

erty title that is valid in time (duration), in geographic space

(range) and in the world of objects (scope or extent of the

patent). Filing a patent application means dening a set of

claims concerning the concretization or application of an

idea. After an investigation into anteriority and in some

cases a study of patentability, the patent authority may or

may not grant property rights for a particular geographical

area specified in the application. In exchange for patent

rights the inventor has to divulge publicly the technical

details on the new knowledge.

Certain legal limits ensure that not all the knowledge

produced by an economic agent is patented. Patentability of

knowledge depends on conditions of absolute innovative-

ness of the invention, of non-obviousness for an expert, and

of the possibility of industrial application (or utility). Theo-

retically, the condition of non-obviousness (or inventive

activity) is intended to distinguish between that which is

essentially the product of creative human work and that

which is primarily the work of nature. One can patent a new

machine but one cannot patent a fresh water spring even if

one has discovered it. As a result, recurrent debate on the

nature of innovation in certain disciplines such as mathe-

maticsis it an invention or a discovery?has extensive

economic implications. The interpretation of this criterion

is of course at the heart of discussions on the patentability of

genetic creations.

One should note that the protection afforded by a prop-

erty right is neither automatic nor free. The

onus is on the patent owner to iden-

tify the counterfeiter and take

the matter to court, where it

will be assessed and inter-

preted. The effectiveness of

property rights is therefore

inseparable from the cre-

ators capacity to watch

over them. These capac-

ities depend, in turn, on

legal facilities (can someone be sued

73 isuma

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

for counterfeit?), technical capacities (microscopic analysis)

and organizational capacities (information networks).

Moreover, globalization of markets clearly has a negative af-

fect on these surveillance capacities.

Patent: between exclusion and diffusion of knowledge

The patent provides an obvious and recognized solution to

the economic problem of the intellectual creator. By in-

creasing the expected private returns from an innovation, it

acts as an incentive mechanism to private investments in

knowledge production. The problem is that by imposing

exclusive rights, the patent restricts de facto the use of

knowledge and its exploitation by those who might have

beneted from it had it been free. These situations occur

because the person who has the knowledge is not necessar-

ily in the best position to use it efciently. The more dis-

tributed knowledge is, passing from hand to hand, the

greater the probability of it being exploited effectively. It is

therefore important to nd some balance between the right

to exclusivity and the distribution of knowledge.

A medium for the dissemination of knowledge

Different devices exist for deliberately organizing the circu-

lation of knowledge in a patent system. First, the granting of

a property right is accompanied by public disclosure con-

cerning the protected technique. There is therefore dissem-

ination of knowledge owing to the patent. Albeit partial

(only the codied and explicit dimensions of the new knowl-

edge are described), this dissemination is particularly im-

portant in certain industries. If it is carried out in time,

and in so far as the information thus constituted is avail-

able at a low cost, it allows for a better allocation of re-

sources, reduces the risk of duplication and favours the trad-

ing of information. The case of pharmaceuticals clearly

illustrates the use of patents as a means of information and

co-ordination. Patent databases are a unique medium for

knowledge externalities. Each rm uses them to evaluate its

own strategies and identify opportunities for co-operation or

transactions concerning knowledge. Second, patents create

transferable rights.

Getting a good balance

It is thus important to achieve an appropriate balance be-

tween the exclusion value and the dissemination value. Such

a balance is based on the institutional articulation of ip that

can vary a great deal across countries.

For example, the information disclosure rules matter:

1

The

Japanese system is effective for sending signals and placing a

large amount of information in the public domain, thus

contributing to the essential objective of collective inven-

tion. While the European system tends also to have an effec-

tive signalling function (though less powerful), the U.S.

system, until recently, was not effective in terms of signalling.

Minor institutional differences are important to explain the

disparities of the value of patents as a source of information

and, thus, as a mechanism for efcient coordination. When

information is properly disseminated (as in the Japanese

system) and when the nature of the protection granted is

specified in ways that encourage patentees to make their

innovations available for use by others at reasonably modest

costs (narrow patent as well as weak degree of novelty are

crucial in this way), the patent system becomes a vehicle for

co-ordination in expanding informational spillovers, rather

than for the capture of monopoly rents.

But nding the appropriate balance also depends on the

kind of knowledge considered. And here the cumulative

nature of knowledge has to be recognized as a decisive

parameter: the social cost of exclusion increases as knowl-

edge becomes more cumulative. In this sense it is not possi-

ble to consider and treat in similar terms knowledge as a

consumption good and knowledge as an investment good

likely to spawn new (knowledge) goods. The more cumu-

lative the use, the more social losses will be generated by

stronger IP rights.

WHO OWNS THE KNOWLEDGE ECONOMY?

Unbridled privatization of knowledge bases

Many signs suggest that use of intellectual property is be-

coming increasingly important and that within this general

domain, use of the patent is growing rapidly. The greater in-

tensity of innovation, characteristic of the knowledge-based

economy, and the increase in the propensity to patent (that

is, the elevation of the ratio number of patents/number of

innovations) which indicates the emergence of new research

and innovation management techniques, are the main fac-

tors of this quantitative evolution.

2

A recent article in the

Wall Street Journal cites startling figures for the United

States: 151,024 patents were granted in 1998, correspond-

ing to an increase of 38 percent compared to 1997. But the

evolution is also qualitative. Patents are being registered on

new types of objects such as software (17,000 patents last

year, compared to 1,600 in 1992), genetic creations and

devices for electronic trade over the Internet, and by new

players (universities, researchers in the public sector). This

general trend is also reected in the increase in exclusivity

rights over instruments, research materials and databases.

All this contributes to the unprecedented expansion of the

knowledge market and the proliferation of exclusive rights

on whole areas of intellectual creation.

3

Explanations

This trend is partly driven by three types of institutional

changes that are resulting in a privatization of knowledge

that used to be a public good!

powerful commitments to basic research by private rms

in certain sectors (this is, for instance, the case in the

genomics area where we can observe the emergence of a

new generation of firms that are highly specialized in

fundamental research and are, therefore, in direct compe-

tition with the public research institutions);

changes in the behaviour of open science institutions

which are increasingly oriented toward the promotion

of their commercial interests;

4

privatization of governmental civilian agencies which

become major players in the contractual research market.

5

74 Spring Printemps 2002

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

This evolution is to a large extent determined by how

patent ofces and courts in the United States and Europe

interpret the three basic patentability criteria. Courts and

patent offices have always played a role of regulation,

blocking or slowing down private appropriation in certain

elds. For example, the patentability criteria of industrial

application (utility) was a very effective basis for block-

ing the patenting of the rst genetic inventions in the late

1980s. Nowadays, patentability criteria are being applied in

such a way as to allow most research results to be

patentable. This increasing ability to patent fundamental

knowledge, research tools and databases is part and parcel

of a broader movement toward strengthening iprs.

From one IP conception to another

This trend does not necessarily lead to an excess of privati-

zation of knowledge. Far from it. In many cases the estab-

lishment of intellectual property rights strengthens private

incentives, allows the commitment of substantial private

resources and thereby improves the conditions of commer-

cialization of inventions. Moreover, the establishment of

private rights does not totally prevent the diffusion of

knowledge, even if it does limit it. Finally, a large propor-

tion of private knowledge is disseminated outside the mar-

ket system, either within consortiums or by means of net-

works of trading and sharing of knowledge, the foundation

of the unintentional spillovers discussed earlier on.

There is, however, cause for concern when all these

evolutions seem to be in the same direction, strengthening

iprs.

6

Traditionally, iprs were considered one of the incen-

tive structures society employed to elicit innovative effort.

They co-existed with other incentive structures, each of

which has costs and benets as well as a degree of comple-

mentarity. We seem to be moving toward a new view, in

which iprs are the only means to commodify the intangible

capital represented by knowledge and should therefore be a

common currency or ruler for measuring the output of

activities devoted to knowledge generation and the basis

for markets in knowledge exchange.

Implications: higher transaction costs

and potential blockages

A rst range of implications involves various phenomena,

which can be grouped, for the sake of convenience, under

the heading of transaction costs increases. First, sub-

stantial ipr-related transaction costs may increase to such

an extent that the result can be the blockage of knowledge

exploitation and accumulation. We might characterize this

as an excess of privatization. Second, efforts and costs

devoted to sorting out conicting and overlapping claims to

ipr will increase as will uncertainty about the nature and

extent of legal liability in using knowledge inputs.

Patent scope and anti-commons

We have an excess of privatization when private property

rights block the exploitation of the knowledge that these

rights are in fact meant to improve. We have identied two

such situations. First, initial patents that are too broad and

reward the pioneer inventor too generously, block possi-

bilities for subsequent research by others and thus reduce

the diversity of innovators in a eld and the probability of

cumulative developments.

7

Second, an excess of privatiza-

tion relates to excessive fragmentation of the knowledge

base, linked to intellectual property rights on parcels and

fragments of knowledge that do not correspond to an in-

dustrial application. This situation is described by the con-

cept of an anti-commons regime and illustrated with the

case of biotechnology: when private rights are granted to

fragments of a gene, before the corresponding product is

identied, nobody is in a position to group the rights (i.e.,

to have all the licences) and the product is not developed.

8

Basically, these problems stem from the fact that patents

and innovations are two different realities that do not coin-

cide. In some cases a single patent covers many innovations

(especially when the eld is too large or when the patent

protects generic knowledge). In other cases, a single inno-

vation is covered by many patents. This case is the anti-

commons regime.

By staking a set of claims, inventors delimit the territory

they want to have recognized as their property (the same

principle as fencing off a eld). If the eld more than covers

the territory of the innovation, subsequent innovations by

other inventors, based on the rst one, will be blocked. But

if the eld is too narrow, the pioneers efforts may not be

rewarded at their full value. Note that a large eld is not a

major problem in the case of a discrete innovation. The

metaphor of minerals prospection is useful here. In a given

territory where there is only one deposit surrounded by

nothing else, whether the prospector closes off the territory

very close to the deposit or far from it, creating a vast eld,

makes no difference since the additional space appropri-

ated is of no value.

The problem is different in the case of interdependent

and cumulative innovations. If an initial patent is too broad,

it blocks possibilities for subsequent research by others. It

thus reduces the diversity of innovative agents in the

domain and the probability of cumulative developments

taking place. A case in point is breast cancer genetics where

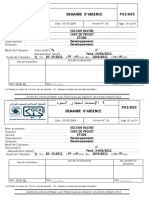

F I GUR E 1

The distinction between private and anti-commons property

12

1

A

2

B

3 2 3

C

1

A

B

C

Anti-commons property Private property

75 isuma

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

patents owned by private companies protect all reproduc-

tion and use of the sequence and related products, includ-

ing diagnosis, irrespective of the technique used. Very broad

patents are a real problem in the life sciences, for example

in genomics, as a number of recent studies suggest.

9

After studying numerous cases, Merges and Nelson

suggest that, in a context of interdependent innovations, an

intellectual property policy that allows very broad patents

leads to a number of blockages which have an impact on

the general dynamics of innovation in the sector: In the

cumulative systems technology cases, broad, prospect claim-

ing, pioneer patents, when their holders tried to uphold

them, caused nothing but trouble Nor is there reason to

believe that more narrowly drawn patents would

have damped the incentives of the pioneers and

other early comers to the eld.

10

Another type of situation is called anti-

common to indicate that its consequences

are the exact inverse of the effects of

common resources. It is a situation that

has produced parcels of private prop-

erty rights on indivisible goods,

11

so

that each party, being the owner of a

portion of the indivisible good, has the

right to exclude others from its share

and no one has the effective privilege of

use. The distinction between the private

property regime and the anti-common regime

is represented in the following figure where

goods 1, 2 and 3 are represented by cells, and the

initial property rights of individuals A, B and C are repre-

sented by lines in bold type.

The private property regime structures the material world

vertically because owners A, B and C each own exclusive

rights, 1, 2 and 3 to an entire good (e.g., a piece of land). In

other words, this regime does not prohibit exploitation of

the resource. In the anti-common regime the lines are hori-

zontal since private rights fragment the goods.

Tragedy results from the fact that multiple owners of

parcels or fragments of a good each have the right to

exclude others from their parcel, so that nobody can exploit

the good in its entirety. This property regime thus breaks

down and fragments objects. If too many owners have such

exclusive rights (i.e., if there is too much fragmentation),

there is a chance that the good will be under-utilized.

How does this regime apply in the knowledge economy?

It corresponds to excessive fragmentation of the knowledge

base: in genomics, rights are created on portions of knowl-

edge before the corresponding product is identied (whereas

previously it was the genes corresponding to products that

were patented, e.g., therapeutic proteins, diagnostic tests).

The proliferation of patents on fragments of genes owned

by different agents hugely complicates the co-ordination

required by an agent wanting to develop a product. In

particular, if the acquisition of all necessary licences is too

complicated or expensive, the product will never material-

ize.

13

Certain situations in the domain of icts also pose this

type of problem.

The explosion of litigation costs

There is a persistent policy debate in the United States about

the litigation explosion. The U.S. patent system has seen a

dramatic increase in both litigation and administrating pro-

ceedings over the past decade. Critics have suggested that the

1982 reform of the patent system has led to aggressive ef-

forts by large rms to extract favourable settlements from

smaller concerns.

14

Beyond the direct cost for the economy,

Lerner

15

estimates indirect costs, which correspond to the

distortion of innovative behaviours of small companies. For

example, small companies in biotechnology try to avoid un-

dertaking research in elds with many previous awards by

rival biotechnology companies and they tend to choose less

crowded elds. Moreover, those companies tend

to avoid elds with companies having large

experience in litigation. Such behaviours

introduce new bias in the choice of

r&d projects, which increase a risk

of sub-optimality in the process of

resource allocation among those

various research elds.

Certain national patent systems

have some peculiar features that

prove to be effective in minimiz-

ing that problem. For example,

European and Japanese systems

provide for the possibility of oppos-

ing the application before the rights

have been granted. This is possible on

condition that information concerning the

application is published early enough (within 18 months

of the application). These mechanisms can avoid potential

conict, a source of high legal costs. In the United States,

where publication occurs at a later stage, once the property

rights have been granted, this possibility of pre-empting

conict is not used. Late publication of information creates

legal uncertainty.

The patent-granting culture matters. The fact of being

indulgent with inventors by granting them everything they

apply for (e.g., a patent that includes subsequent develop-

ments, which are not yet dened) creates fragile areas in

the protection of rights and increases the likelihood of

conict. A patent more strictly limited to innovation reduces

the probability of future conict.

The institutional diversity is in danger

The asymmetric fragility of open science

Open science is caught between the constraints of public

budgets (to be related to the increase in scientic research

costs) and growing demands from rms for research ser-

vices (following the restructuring of these rms and the con-

sequent outsourcing of their r&d activities). In this context

we witness increasing commercialization of open science

activities.

16

This represents a real risk of irremediable al-

teration of modes of co-operation and sharing of knowl-

edge. Restricted access to knowledge and the retention of

knowledge produced by universities comes in several forms,

76 Spring Printemps 2002

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

e.g., delayed or partial publication and communication, se-

crecy and patents. A signicant form is the exclusive licence

(new knowledge is sold exclusively to one rm). When there

is nothing left but exclusive bilateral contracts between uni-

versity laboratories and rms, we have forms of quasi-in-

tegration that undermine the domain of open knowledge.

As well developed by Argyres and Liebeskind,

17

univer-

sity institutional mechanisms have been designed to develop

and protect the intellectual commons, not to exploit it.

Weakening these institutional mechanisms to any signicant

degree may rob the university of its unique identity and func-

tion as a social institution, and end with its capture by private

interests. As a matter of illustration, Mowery et al. note

that in the United States new laws authorizing universities

to grant exclusive licences on the results of research nanced

by public funds (especially the Bayh-Dole Act) are based on

a narrow view of the channels through which public research

interacts with industry. In reality these channels are multiple

(publication, conferences, consultancy, training, expertise)

and all contribute to the transfer of knowledge, while the

incentives created by such laws promote only one channel

(patenting and licences), with the risk of blocking the

others. The authors conclusion is unambiguous: The

Bayh-Dole Act and the related activities of U.S. univer-

sities in seeking out industrial funding for collaborative

R&D have considerable potential to increase the

excludability of academic research results and to

reduce the knowledge distribution capabilities

of university research.

18

Institutional diversity in danger

A further cause for concern is the

fact that the diversity of institu-

tional arrangements are being

undermined. The various institu-

tions, be they public, private or a

mix of the two, each fulls spe-

cific functions and some

strong complementarities

exist between them. However,

the space for public research is shrink-

ing, and functions which were assumed by open

science are no longer assumed at the same level.

Excessive privatization may undermine the long-term

interests of industry itself (which will benet from less public

knowledge, less training and screening externalities). Further-

more, the scenario of a pure functional substitution (the

private sector would simply carry out the functions that were

formerly assumed by the public sector) is wrong. We know

that private companies will never fund the same type of basic

research that the public sector abandons.

19

Similarly, the need

for scientic training could be satised only very partially by

market-based institutions. As argued by Cohen et al.,

20

the

spillovers from the downstream r&d conducted by rms

engaged in basic research are not likely to fully substitute for

the information ows initially blocked for several reasons.

First, rms will try to restrict spillovers to retain proprietary

advantage. Second, there will typically be considerable lags

between the time the rm receives the privileged informa-

tion and the time information spills over to the other rms.

Economic studies on the U.S. model reveal, thus, a degree

of concern. We note one of the conclusions of Cockburn

and Henderson: policies which weaken these institutions

[of open science], make public sector researchers more

market-oriented, or redistribute rents through efforts to

increase the appropriability of public research through

restrictions in the ways in which public and private sectors

work with each other, may be therefore counter-productive

in the long run.

21

This is a strong conclusion that prompts

us to scrutinize this new model without being blinded by

the brilliance of its undeniable short-term performance.

NEED FOR NEW POLICIES

In the knowledge economy:

good fences do not make good neighbours

As Paul David claims, good fences make probably good

neighbours where the resource is land or any other kind of

exhaustible resources.

22

But simple considerations of the

public goods nature of knowledge suggest that this is not

so when the resource considered is knowledge. Knowl-

edge is not like forage, depleted by use for consumption;

data-sets are not subject to being over-grazed but, in-

stead, are likely to be enriched and rendered more accu-

rate, and more fully documented the more that re-

searchers are allowed to comb through them.

Thus, the shift toward a new policy mix is raising

many problems and may lead ultimately to major social

losses. In most research elds, creative discovery

comes from unlikely journey through

the information space.

23

If too

many property rights are assigned to

the micro-components of the informa-

tion space, travelling through it proves to

be extremely costly, even impossible, because

at every point the traveller must nego-

tiate and buy access rights. We are

facing here a great paradox that iprs,

which are traditionally used to support the

exploitation of knowledge, are becoming ulti-

mately a way to shrink the knowledge base.

Of course, the new system of knowledge produc-

tion generates its own regulation, which can bring about a

certain equilibrium in some instances. We can list four

classes of solutions, dealing with the various problems devel-

oped below.

1. Mechanisms are devised to support, in certain circum-

stances or for certain classes of economic agents, the fast

dissemination and free exploitation of private knowledge.

There are three main mechanisms:

Compulsory licensing (compulsory diffusion of private

knowledge for the general interest).

The State or international foundations buy patents to

put them back in the public domain. To illustrate this

mechanism Kremer

24

uses the historical case of

Daguerre, the inventor of photography who neither

77 isuma

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

exploited his invention nor sold it for the price he

wanted. In 1839 the French government purchased the

patent and put the rights to Daguerres invention in the

public domain. The invention was developed very fast!

Ramsey pricing rule suggests price discrimination

between users whose demands are inelastic and those

for whom the quantity purchased is extremely price-

sensitive. The former class of buyers therefore will bear

high prices without curtailing the quantity purchased of

the goods in question, whereas the low prices offered to

those in the second category (e.g., scholars and univer-

sity-based researchers) will spare them the burden of

economic welfare reducing cutbacks in their use of the

good.

25

2. Granting non-exclusive licences, presumably with mini-

mal diligence or exclusive licences with diligence, offers

a partial solution to the problem of licensing knowledge

produced by publicly funded research programs in

universities.

3. Cross-licensing mechanisms may be a way out of the

anti-commons trap. Transactions costs can be reduced

through mutual concessions and through the trading of

rights (for example, within a consortium). However, this

is a solution that can only work with a small number of

companies. In that regard, the rapid growth of new kinds

of firms does caution against over-confidence that the

anti-commons problems can be surmounted. For exam-

ple, the computer hardware industry had few problems

with its cross-licensing arrangements, until new kinds of

semi-conductor companies arose.

4. There is a great deal to be done in terms of the ways in

which patent offices enforce patent requirement (i.e.,

make their assessments of utility requirement, non obvi-

ousness, patent scope). One should note however that

hybrid and complex objects such as genes, dna

sequences, software, databasesgenerate a lot of uncer-

tainties about what ipr policy is appropriate, making the

tasks of patent offices very difficult. It is difficult to

provide non-ambiguous and clear answers to the ques-

tion whether these new objects should be privately appro-

priated; and if yes, what class of ipr should be used.

However, the main policy challenge is far beyond the

implementation of those partial solutions. It deals with the

achievement of the right balance in the joint deployment of

the three institutional devices. With such a balance, the

system can be expected to nd quite naturally the proper

appropriability mechanism for each kind of knowledge

(whether the knowledge is highly cumulative or is more like

a nal product or like a consumption capital). However,

meeting such a challenge is strictly dependent upon restor-

ing some large public and private funding to the patronage

system. The reinforcement of the patronage system has to be

combined with the provision of some kind of intellectual

property aiming at protecting a good from private appropri-

ation (something like a general public licence used to protect

open software). A large room for policy thinking deals,

nally, with the creation of new categories of intellectual

property such as that of the common good. The latter is

proposed by lawyers who think that some new complex and

hybrid objects (like genes) do not t in the usual categories of

private-public goods and propose to work on a new cate-

gory: the common good. Under a common good regime,

innovation dees patrimonial and commercial appropriation.

The private company that is in possession of it for industrial

exploitation is not the owner of the good but serves as a sort

of manager. Such a regime would allow for the emergence of

an industry while avoiding private and exclusive rights.

Understanding what a strong

patent systems actually means

The arguments developed here may create the impression

that we are pleading for shifting towards a weaker patent

system. Before saying that, one needs a more precise den-

ition of what is a strong (and a weak) patent system. The

idea of strong has not necessarily to be related with the

exclusionary value of patent. In fact, many of the solutions

proposed are weakening the exclusionary value, while

strengthening the system as a whole. Compulsory licens-

ing, Ramsey pricing rule, narrower patent, new common

goods regime and licences with diligence are actually means

to diminish the private value of individual increments to

the privately owned knowledge base, even though they may

raise its social value. Approaching that problem dictates

that we make more attractive the forms of intellectual prop-

erty protection that require detailed disclosure and generate

informational spillovers. This can be done by educating

people that all these various solutions, in fact, contribute

to the strengthening of the system by reducing legal uncer-

tainties and the probability of legal conicts and litigations,

and thus increasing the condence of agents to the system.

Reinforcing the protection of IP, which is a matter of

institutional and legal adjustments (in the sense of unifying

patent doctrine for minimizing ambiguities and uncertain-

ties in patent suits or of decreasing the cost of patent appli-

cation or improving enforcement conditions) aiming at

increasing legal certainty, does not mean reinforcing the

exclusivity value of patents, which impedes knowledge

dissemination and the collective progress of industries. And

actions and policy recommendations aimed at reducing the

exclusion value of patents are compatible with this version

of what a strong system of iprs is.

Dominique Foray is Principal Administrator at the Center for Education,

Research and Innovation, OECD. This paper has beneted immeasurably from

previous and present collaborative projects with R.Cowan, Paul David,

Bronwyn Hall, Jacques Mairesse and Ed Steinmueller. Insightful discussions

with them as well as the remarks of participants to the EC STRATA workshop

on IPR aspects of integrated Internet collaborations (Brussels, January 22-23,

2001) have contributed substantially to improving the exposition.

Endnotes

1. W. Cohen, A. Goto, A. Nagata, R. Nelson and J. Walsh, r&d

Spillovers, Patents and the Incentives to Innovate in Japan and the

United States, Working Paper (2001).

2. S. Kortum and J. Lerner, Stronger Protection or Technological

Revolution: What Is Behind the Recent Surge in Patenting? Harvard

Business School, Working Paper (1997), pp. 98-012.

3. A. Arora, A. Fosfuri and A. Gambardella, Markets for Technol-

ogy(Why Do We See Them, Why Dont We See More of Them,

78 Spring Printemps 2002

intellectual property and innovation in the knowledge-based economy

and Why We Should Care), Universidad Carlos iii de Madrid,

Working Paper (1999).

4. R. Henderson, A. Jaffe and M. Trajtenberg, Universities as a

Source of Commercial Technology, Review of Economics and Statis-

tics (February 1998).

5. A. Jaffe and J. Lerner, Privatizing r&d: Patent Policy and the

Commercialization of National Laboratory Technologies, nber,

Working Paper, no. 7064 (1999).

6. W.E. Steinmueller, Problems and Challenges of Integrated Inter-

net Collaborations in the Intermediate Area Where Both Commer-

cial and Open Science Issues Are Operative, strataetan

Workshop, Brussels (January 22-23, 2001).

7. S. Scotchmer, Standing on the Shoulders of a Giant, Journal of

Economic Perspectives, Vol. 5, no. 1 (1991).

8. M. Heller and R. Eisenberg, Can Patents Deter Innovation? The

Anticommons in Biomedical Research, Science, Vol. 280 (1998).

9. M. Cassier and D. Foray, Appropriation Strategies and Collec-

tive Invention: New Findings from Case Studies, International

Conference, Paris (November 19, 1999), sessi, French Ministry of

Industry; S.M. Thomas, Les brevets en surrgime, Biofutur, Vol.

191 (1999).

10. R. Merges and R. Nelson, On Limiting or Encouraging Rivalry

in Technical Progress: The Effect of Patent Scope Decisions, Journal

of Economic Behavior and Organization, Vol. 25 (1994).

11. M. Heller, The Tragedy of the Anticommons: Property in the

Transition from Marx to Markets, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 111,

no. 3 (1998).

12. Heller, ibid.

13. M. Heller et al., op.cit.

14. A. Jaffe, The U.S. Patent System in Transition: Policy Innovation

and the Innovation Process, nber, Working Paper no. 7280 (1999).

15. J. Lerner, Patenting in the Shadow of Competitors, Harvard

Business School, Working Paper (1994).

16. D. Foray, Science, Technology and the Market, World Social

Science Report (London: unesco Publishing/Elsevier, 1999).

17. N. Argyres and J. Porter Liebeskind, Privatizing the Intellectual

Commons: Universities and the Commercialization of Biotechnology,

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 35 (1998).

18. D.C. Mowery, R.R. Nelson, B. Sampat and A.A. Ziedonis, The

Effects of the Bayh-Dole Act on US University Research and Technol-

ogy Transfer: An Analysis of Data from Columbia University, the

University of California, and Stanford University, Kennedy School

of Government, Harvard University (1998).

19. K.M. Brown, Downsizing Science (Washington DC: The aei Press,

1998).

20. W.M. Cohen, R. Florida, L. Randazzese and J. Walsh, Industry

and the Academy: Uneasy Partners in the Cause of Technological

Advance, in R. Noll (ed.), Challenge to the Research University

(Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1998).

21. I. Cockburn and R. Henderson, Public-Private Interaction and

the Productivity of Pharmaceutical Research, nber, Working Paper,

no. 6018 (1997).

22. P.A. David, Digital technologies, Research Collaborations and

the Extension of Protection for Intellectual Property in Science: Will

Building Good Fences Really Make Good Neighbors?

strataetan Workshop, op. cit, supra note 6.

23. G. Cameron, Scientic Data, the Electronic Era, Intellectual Prop-

erty, ibid.

24. M. Kremer, Patent Buy-Outs: A Mechanism for Encouraging

Innovation, nber, Working Paper no. 6304 (1997).

25. P.A. David, The Digital Technology Boomerang: New Intellectual

Property Rights Threaten Global Open Science, forthcoming in the

World Bank Conference Volume: abcde2000.

INSTITUTE FOR RESEARCH ON PUBLIC POLICY

McGILL-QUEENS UNIVERSITY PRESS

The Review of Economic Performance and Social Progress,

2001

Edited by Keith Banting, Andrew Sharpe and France St-Hilaire

The rst volume in a new series that will

review the current state of economic

performance and social progress in Canada

and other countries.

ISBN 0-88645-190-6 $24.95

A State of Minds

Toward a Human Capital Future for Canadians

Thomas J. Courchene

A comprehensive analysis of the key

challenges of the information era.

Courchene is one of our most provocative,

and best, policy thinkers.

Saturday Night

ISBN 0-88645-188-4 $24.95

You might also like

- Expressions Pour Production EcriteDocument5 pagesExpressions Pour Production Ecritechiedoanh100% (2)

- Correction Histoire Geo Voie G Sujet2Document3 pagesCorrection Histoire Geo Voie G Sujet2LETUDIANT83% (6)

- Creperie Business PlanDocument23 pagesCreperie Business PlanR'kia RajaNo ratings yet

- Guide-Technique YTONG MULTIPOR Edition1Document116 pagesGuide-Technique YTONG MULTIPOR Edition1Yassine AyariNo ratings yet

- Allocution President CONVEN 6010Document8 pagesAllocution President CONVEN 6010SADJIA EL BEYNo ratings yet

- Du Syndicalisme Au SénégalDocument19 pagesDu Syndicalisme Au SénégalCheikh ThiamNo ratings yet

- Entr Pre Unari atDocument3 pagesEntr Pre Unari atRokaya JawadNo ratings yet

- b2 - Revue de Presse - Les C3aeles ArtificiellesDocument3 pagesb2 - Revue de Presse - Les C3aeles ArtificiellesMinh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- F02-600 Demande D'absence GICADocument1 pageF02-600 Demande D'absence GICASOLTANINo ratings yet

- Tema 1Document10 pagesTema 1Stanislav1999No ratings yet

- Amor Rebelde - Corazón SerranoDocument16 pagesAmor Rebelde - Corazón SerranoGilmer Farceque AlbercaNo ratings yet

- Chapitre 17 Les Soldes Intermediaires deDocument13 pagesChapitre 17 Les Soldes Intermediaires deyannickNo ratings yet

- Al Khazina 4Document26 pagesAl Khazina 4HATIM ESSAHIRINo ratings yet

- Rapport Etats FinanciersDocument27 pagesRapport Etats FinanciersAymaneNo ratings yet

- Droit Du TravailDocument86 pagesDroit Du TravailMohammed OumniaNo ratings yet

- CHAB' LE JOURNAL DES JEUNES Loran 2 BDDocument20 pagesCHAB' LE JOURNAL DES JEUNES Loran 2 BDI'm jujusdecanneNo ratings yet

- ANNEXE 1 CMO 6 Mois Modele Convocation Agent Annexe 1Document1 pageANNEXE 1 CMO 6 Mois Modele Convocation Agent Annexe 1maeva dasilvaNo ratings yet

- Boal 44 45 0Document70 pagesBoal 44 45 0shamsoudin100% (1)

- Corrigé Les Provisions 2019 2020Document6 pagesCorrigé Les Provisions 2019 2020Samantha MayaNo ratings yet

- Des Vertus de La ParesseDocument1 pageDes Vertus de La ParesseTalavera Pimentel AmingNo ratings yet

- Choisir La Forme Juridique de Mon EntrepriseDocument13 pagesChoisir La Forme Juridique de Mon Entrepriseimène masmoudiNo ratings yet

- Cour de Cassation Civile Chambre Civile 1 18 Decembre 2014 14 11085 Publie Au Bulletin 18 07 2023 19 12 44Document4 pagesCour de Cassation Civile Chambre Civile 1 18 Decembre 2014 14 11085 Publie Au Bulletin 18 07 2023 19 12 44Gustavo alonso DELGADO BRAVONo ratings yet

- Clement ThibautDocument24 pagesClement ThibautCésar Pérez GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Etapes Pour Les Formalites CanadienDocument49 pagesEtapes Pour Les Formalites CanadientcoffopharellNo ratings yet

- Rapport PFE Mansour Boussandel PDFDocument111 pagesRapport PFE Mansour Boussandel PDFchaima zrelliNo ratings yet

- PFE Groupe 3 L'acceptabilité de La Finance Islamique Par Les Clients de La Banque Marocaine.Document32 pagesPFE Groupe 3 L'acceptabilité de La Finance Islamique Par Les Clients de La Banque Marocaine.mohamed khadroufNo ratings yet

- La Fiscalité Et La Politique Économique - Exposé - FIDocument11 pagesLa Fiscalité Et La Politique Économique - Exposé - FIraniaNo ratings yet

- GRENADEDocument6 pagesGRENADENzaou jessyNo ratings yet

- a-baleine-gourmande-TIKTAKTOE MERDocument9 pagesa-baleine-gourmande-TIKTAKTOE MERDeolinda SilvaNo ratings yet