Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kenneth Frampton Interview Explores Graphic Expression in Architecture

Uploaded by

N. Miguel SeabraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kenneth Frampton Interview Explores Graphic Expression in Architecture

Uploaded by

N. Miguel SeabraCopyright:

Available Formats

Kenneth Frampton

es, por encima de

todo, un arquitecto

de exquisita

sensibilidad en

todas las facetas

que engloban la

arquitectura.

Kenneth Frampton

is, above all, an

architect with an

exquisite

sensitivity in all

areas that include

architecture.

KENNETH FRAMPTON

conversando con

Laura Lizondo

26

Como parte de mi tesis doctoral

Arquitectura o Exposicin?: Fundamentos

de la Arquitectura de Mies van der Rohe ,

he realizado una estancia en la GSAPP de

la Universidad de Columbia. Aqu he tenido

el placer de conocer a Kenneth Frampton,

quien ha sido el tutor de mi tesis durante

cuatro meses y con quien he tenido el

gusto de compartir ms de una

conversacin. Una de ellas tiene como

resultado esta entrevista, realizada el 12

de Diciembre de 2011. Laura Lizondo.

As part of my PhD thesis Architecture or

Exhibition? The Foundations of Mies van

der Rohes Architecture, I have been a

visiting scholar at GSAPP of Columbia

University. There I have had the pleasure

of meeting Kenneth Frampton, who has

been my PhD tutor for four months, and I

have enjoyed the pleasure of sharing a

number of conversations. One of them has

resulted in this interview, carried out on

December 12th, 2011. Laura Lizondo.

27

e

x

p

r

e

s

i

n

g

r

f

i

c

a

a

r

q

u

i

t

e

c

t

n

i

c

a

conversando con KENNETH FRAMPTON

School of Architecture, Planning

and Preservation (GSAPP) at

Colombia University in New York.

Every architect knows his writing

and every researcher has, as part

or his or her reference

bibliography, his books and

articles due to their philosophical

and critical interest. Also, I dont

need to mention the quality and

variety of his lectures, which after

more than three decades, continue

to retain all their validity, and are

followed by many architects. He

creates excitement wherever he

goes and I wonder what is

Kenneth Framptons secret? What

causes him to make any enthusiast

of architecture, who read his work

or who like me have had the good

fortune to listen to him speak,

shudder with excitement? Maybe

the key is his tireless research

work never anchored in what is

already known, but also exploring

new concepts; never focused on a

particular field of architecture, but

also studying within the global

framework; never understood only

from the educational aspect, but

also analysing from the special

characteristics and peculiarities of

each culture.

Conocido por sus grandes

aportaciones a la crtica

arquitectnica y por su

extenssima labor docente,

Kenneth Frampton es, por encima

de todo, un arquitecto de exquisita

sensibilidad en todas las facetas

que engloban la arquitectura.

Arquitecto desde 1956 por la

Architectural Association de

Londres, lleva ms de media vida

trabajando en Nueva York, en lo

que el ha denominado las tripas

hoy sucias de los Estados Unidos.

Ha sido Profesor Asociado en

universidades de la talla de

Princeton, Profesor Visitante en

medio mundo y desde 1974 est a

cargo de la Ctedra Ware en la

Graduate School of Architecture,

Planning and Preservation

(GSAPP) de la Universidad de

Columbia en Nueva York. Todo

arquitecto conoce sus escritos y

cualquier investigador que se

preste, tiene como parte de su

bibliografa de consulta sus libros

y artculos por el inters filosfico

y crtico que despiertan. Tampoco

hace falta mencionar la variedad y

calidad de sus clases magistrales,

que despus de ms de tres

dcadas, siguen conservando toda

su vigencia y son seguidas por

multitud de arquitectos. All donde

va crea expectacin y yo me

pregunto, cul es el secreto de

Kenneth Frampton? Qu provoca

que siga estremeciendo a

cualquier entusiasmado de la

arquitectura que lea su obra, o a

quienes como yo tienen la suerte

de poder escucharlo? Quiz la

clave est en su incansable labor

investigadora nunca anclada en lo

ya conocido, sino explorando

nuevos conceptos; nunca

centrada en un campo concreto

de la arquitectura, sino estudiada

desde la globalidad: y nunca

entendida nicamente desde la

universalidad, sino analizada

desde las particularidades de

cada cultura.

Well-known for his great

contribution to architectural

criticism and his very extensive

teaching, Kenneth Frampton is,

above all, an architect with an

exquisite sensitivity in all areas

that include architecture. An

Architect since 1956 for the

Architectural Association School

of London, he has worked half his

life in New York, which he referred

to as the dirty guts of the United

States. He has been Associate

Professor in Universities like

Princeton; a Visiting Professor in

most of the world; and from 1974

he has been a Ware Professor of

Architecture in the Graduate

28 Laura Lizondo: Professor Frampton, many of

the most important architectural influences of

this century have come from the theoretical

architectures which, though not conceived to

be built, were conceived to be shown in

different mass media such as magazines,

exhibitions and competitions. As an example

we have the case of Mies van de Rohe as well

as many other avant-garde architects.

Nowadays, when it is very complicated to build,

I think architectural competitions can be a good

venue for many architects, who may not have

any commissions to show their work. Would

you agree that competitions are a fundamental

way in which architects can visually express

their ideas? Does Kenneth Frampton consider

the graphic expression of architecture as a

valid method of research?

Kenneth Frampton: The first part of the

question has to do with the history of avant-

garde architecture in the twentieth century and

you give Mies as an example but we could just

as easily cite others where the form and content

of the graphic presentation has been crucial to

the aesthetic. Archigram for instance or Italian

Futurism or for that matter some aspects of

Italian Rationalism. Im thinking in case of this

last of the metaphorical dimension in the

presentation drawings of Giuseppe Terragni;

drawings which display quite different values

from the pop imagery of Archigram which tapped

into the pop culture of the 60s and; a reference

was inextricably mixed with advertising as a

way of advancing the vision of a technologically

progressive and seemingly popular architecture.

I think such values are fully incorporated into the

mode of graphic representation; the collaged

figurative elements and bright, chromatic almost

comic strip colors. Along those lines, one should

note that there is a great difference between the

drawings of Archigram and those dry non-

rhetorical drawings of Cedric Price. Although

they share some values in common it is rather

obvious that Price wished to present his work in

the form of strictly minimalist monochromatic

black ink line drawings, perspectival where

necessary, but otherwise reduced to down-to-

earth tectonic data. This surely stems from

Cedrics political position on the left of the

British Labor party prior to the ambivalent

leadership of Tony Blair. In fact is much closer to

the socialist line of Anthony Wedgewood Benn.

This accounts for the Fun Palace, which he

Laura Lizondo: Profesor Frampton, gran

parte de las influencias arquitectnicas

ms importantes de este siglo han veni-

do de la mano de las arquitecturas de

papel, arquitecturas que si bien no fue-

ron concebidas para ser construidas si lo

fueron para ser expuestas en los medios

de comunicacin de revistas, concursos

o exposiciones. Conocemos el caso de

Mies as como el de muchos otros arqui-

tectos de vanguardia. Actualmente, cuan-

do es tan complicado construir, creo que

los concursos de arquitectura pueden ser

una de las vas de salida de tantos arqui-

tectos que no tienen encargos materia-

les. En este tipo de trabajos, estar con-

migo, en que es fundamental la manera

en que se grafan y expresan las ideas.

Considera Kenneth Frampton la expre-

sin grfica de la arquitectura como un

mtodo vlido de investigacin?

Kenneth Frampton: La primera parte de

la pregunta tiene que ver con la historia

de las vanguardias arquitectnicas del

siglo XX, y cita a Mies como ejemplo,

pero fcilmente podramos nombrar a

otros en los que la forma y el contenido

de la representacin grfica han sido cru-

ciales para la esttica. Archigram, por

ejemplo, el Futurismo italiano o algunos

aspectos del Racionalismo italiano. Es-

toy pensando, en este ltimo caso, en la

dimensin metafrica de los dibujos de

Giuseppe Terragni; dibujos que mues-

tran valores muy diferentes de la icono-

grafa pop de Archigramque emergi en

la cultura pop de los aos 60; una refe-

rencia que est unida inextricablemen-

te con publicidad como modo de avan-

zar en la visin de una arquitectura

tecnolgicamente progresista y aparen-

temente popular. Creo que estos valores

estn plenamente incorporados en los

sistemas de representacin grfica, en

los elementos figurativos del collage y

en los colores brillantes, prcticamente

de cmic. En esa lnea, hay que obser-

var que hay una gran diferencia entre los

dibujos de Archigramy de Cedric Price,

serenos y sin retrica. Aunque compar-

ten algunos valores, es bastante obvio

que Price quera presentar su trabajo de

manera estrictamente minimalista, con

dibujos monocromticos de lneas ne-

gras y perspectivas donde fuesen nece-

sarias, pero por lo dems, reducidos a

prcticos datos tectnicos. Esto surge,

seguramente, de la posicin poltica de

Cedric a la izquierda del Partido Labo-

rista britnico, antes del liderazgo am-

bivalente de Tony Blair. De hecho, est

mucho ms cerca de la lnea socialista

de Anthony Wedgewood Benn. Esto se

aplica al Fun Palace, que dise para Jo-

an Littewood, que diriga un teatro de

trabajadores de extrema izquierda en

Stratford East en Londres. En trminos

de concepto y tcnica, el Fun Palace de

Price tena un carcter tanto constructi-

vista como populista. De un modo simi-

lar, las representaciones futuristas de An-

tonio SantElia de la Citt Nuova con su

famosa Casa Gradinate fueron profti-

cas respecto a los nacientes ideales y al

lenguaje de la arquitectura moderna eu-

ropea, empleando la tecnologa moder-

na en las edificaciones en altura de hor-

mign armado y la estructura reticulada

del complejo proyectado, minuciosamen-

te expresado en perspectiva a pesar de

que no haba planos. sta fue la prc-

tica de Archigram, pero no de Cedric

Price. Por tanto, no es slo el grafismo

sino tambin la sustancia del material;

es decir, lo que se muestra y lo que no se

muestra. Lo que est ausente o falta en

un dibujo tambin expresa algo, de he-

cho son un conjunto de valores. En el

caso del arquitecto italiano Carlo Scar-

pa uno puede ver inmediatamente que

la manera de dibujar representa, en gran

medida, la manera de pensar de Scarpa.

Tengo en mente su hbito de dibujar en

sus cartoni en los que trabaja los deta-

lles borrando y redibujando repetida-

mente en sus cartones, expresando el so-

lapamiento mente-mano entre el diseo

y el trabajo manual; la mxima presun-

cin, podramos decir, de un mundo pre

e

x

p

r

e

s

i

n

g

r

f

i

c

a

a

r

q

u

i

t

e

c

t

n

i

c

a

conversando con KENNETH FRAMPTON

digital; tena la costumbre de trabajar so-

bre una cartulina en la que borraba algu-

nas partes y dibujaba de nuevo hasta que

se alcanzaba una fecha lmite, entonces

un ayudante calcaba la ltima versin y

se generaban los dibujos de trabajo.

L.L.: En la Escuela de Arquitectura de Va-

lencia en la cual imparto la asignatura de

primer curso Iniciacin al Proyecto Ar-

quitectnico, existe un debate abierto en-

tre los profesores, en relacin a si el alum-

no debe empezar a proyectar nicamen-

te a mano o combinndolo con las tec-

tologas del ordenador. Mi corta experien-

cia me ha hecho ver que el estudiante sien-

te miedo a la hora de dibujar manualmen-

te y debido a su inexperiencia e ignoran-

cia, piensa que con la mquina sus pro-

yectos van a ser mejores, cosa que casi

nunca sucede. Creo que es importante que

un arquitecto tenga la destreza de impro-

visar un croquis en una servilleta o expre-

sar sus inquietudes a partir de trazos

Qu opina Kenneth Frampton de la in-

fluencia de las nuevas tecnologas a la

hora de crear arquitectura?

K.F.: Ah aparece el fantasma del viejo

debate de si la arquitectura es un arte

o una ciencia aplicada. Este fue un tema

particularmente vigente en los aos 60,

un deseo latente, pragmtico y positivo,

particularmente en el mundo anglo-es-

tadounidense, de transformar la prc-

tica arquitectnica en una especie de

ciencia aplicada. Este fugaz intento sal-

t a la primera plana en Londres, de mo-

do que el departamento de arquitectura

del University College, bajo la direccin

de Richard Llewellyn-Davies, cambi

oficialmente su nombre por el de Scho-

ol of Environmental Studies 1. Despus

volvi a su antiguo nombre, Bartlett

School of Architecture. El debate que

describe no se circunscribe a su Escue-

la. Yo dira que es una situacin gene-

ral, y tengo dos observaciones sobre es-

to. Una es que la gente joven empieza

a usar ordenadores a una edad muy tem-

prana, con los videojuegos por ejemplo,

y por tanto encuentran que dibujar a ma-

no es, a la vez, algo anacrnico, extra-

o y exigente. Esto es seguramente una

apora cultural y conceptual, pero toda-

va es posible ensear a poner las ideas

en papel, de una manera ad hoc. No es

cuestin de resistirse o sustituir lo digi-

tal, sino ms bien una cuestin de am-

pliar su capacidad.

Renzo Piano me dijo una vez que, en su

oficina de Gnova, insista en que el pro-

yecto pasase constantemente por tres pun-

tos: el dibujo a mano, el digital, y la rea-

lizacin de maquetas, y que esta trada se

segua en todas las fases del proyecto, cir-

culando constantemente a travs de estos

tres puntos. sta aproximacin se adhie-

re, como Scarpa, a la idea de que la arqui-

tectura, en un ltimo anlisis, es un oficio

ms que un arte o una ciencia. Uno pue-

designs for Joan Littewood who ran an

extremely left wing workers theatre in Stratford

East in London. In terms of both concept and

drawing technique Prices Fun Palace was as

much Constructivist in character as populist. By

a similar stroke Antonio Sant Elias Futurist

representations of the Citta Nuova with his

famous casa gradinate were prophetic as to the

nascent language and ideals of European

modern architecture employing modern

technology such as multi-story reinforced

concrete, framed construction rising of the

layered complexity all of which was precisely

articulated in the perspective despite the fact

that there were no plans. This was the case with

Archigram, but not with Cedric Price. Thus it is

not only the graphics but also the subject matter

of the drawn material; that is to say what is

shown and not shown. What is missing and

absent in drawing also expresses something, a

set of values in fact. In the case of the Italian

architect Carlo Scarpa one can immediately see

that the manner of drawing very much

represents Scarpas mode of thinking. I have in

mind his habit of drawing and his so called

cartoni on which he would work out the details

erasing and re-drawing incrementally on

cardboard thereby expressing the hand/mind

overlap between draughtsman ship and

craftsmanship; the paramount conceit one might

say of a pre-digital world if I understand

correctly, he was in a habit of developing on a

thin cardboard sheet wherein he would erase

parts by whiting out and drawing over again on

top until a deadline was reached where an

assistant would lay tracing over the latest

version and then produce a working drawing.

L.L.: In the School of Architecture in Valencia,

where I teach basic level class Initiation of

Architectural Project, there is an open debate

among the lecturers regarding whether the

students need to draft by hand or combine this

with computer technology. My brief experience

has shown me that students are afraid when

they have to draw by hand because of their

inexperience and their lack of knowledge leads

them to think that their project will turn out

better with the use of a computer. This belief is

rarely true. I believe that it is important for an

architect to have the skills to improvise a sketch

on a piece of napkin, or to express his or her

ideas from scratch. What do you think on the

subject of the influence of the new technologies

as a means to create architecture?

K.F.: There remains the ghost of that time-

honored debate whether architecture is an art or

an applied science. This was particularly an

issue in the 60s, a latent pragmatic, positivistic

desire, particularly in the Anglo-American World

to transform architectural practice into a kind of

applied science. This short-lived attempt came

to the fore in London, the department of

architecture in University College had its name

officially changed to a School of Environmental

Studies under the Richard Llewellyn-Davies. It

was changed back to its original name, Bartlett

School of Architecture. The debate, which you

describe, doesnt just apply to your school. It is, I

would say, a general condition. And I have two

remarks about this. One is that young people

start to use computers at a very young age with

video games and so on, so that they encounter

drawing by hand is something that is at once,

anachronistic, foreign, and challenging. This is

de sentir todava un vestigio de esto en la

capacidad de produccin de un pas. Te-

nemos la ilusin de que la capacidad tec-

nolgica es la misma en todo el mundo,

pero a menudo, en el trabajo real encuen-

tras sutiles diferencias como cuando com-

paras, por ejemplo, el acero soldado en

Alemania con el producido en la indus-

tria estadounidense de la construccin.

L.L.: Profesor Frampton en alguna oca-

sin me ha comentado acerca de la ca-

lidad y sensibilidad del grafismo de los

proyectos espaoles, tanto dentro de las

universidades como resultado de las

publicaciones. Qu diferencias grficas

considera singulares en el panorama de

la arquitectura dibujada espaola respec-

to a la de otros pases o universidades?

K.F.: Soy de la opinin de que quedan

tres Escuelas de Arquitectura europeas

absolutamente excepcionales: la Royal

Academy en Copenague, la ETSA de

Madrid, y el Departamento de Arquitec-

tura de la Helsinki Technical University.

De los arquitectos formados en estas es-

cuelas se esperaba, y todava se espera,

que sean capaces de integrar el detalle

tcnico con el diseo de la forma cons-

truida, de modo que no haya separacin

entre la capacidad para construir y pa-

ra disear. El currculum, en estas tres

escuelas, sola rechazar que hubiera cual-

quier tipo de separacin intrnseca en-

tre estos aspectos de ser de un arquitec-

to. ste, ha sido hasta hace poco, uno

de los puntos fuertes de la formacin ar-

quitectnica en Espaa, aunque soy

consciente de que el Proceso de Bolonia,

en su bsqueda de uniformizar y des-

regular la prctica arquitectnica en Eu-

ropa es, en la actualidad, una amenaza

directa a este excepcional alto estndar

de formacin de los profesionales, jun-

to con la progresiva disolucin del Co-

legio de Arquitectos de Espaa. S que

a los arquitectos les sola costar graduar-

se ocho aos como trmino medio en Es-

paa, pero la CE desea acortar estos pla-

zos. Esto es parte de una poltica

relativamente antigua del capitalismo

para desregular las profesiones, de mo-

do que puedas obtener ms baratos los

servicios profesionales. A juzgar por una

reciente publicacin del Ministerio de

Fomento espaol, que serva de catlo-

go de una exhibicin de jvenes arqui-

tectos espaoles, todava queda capa-

cidad para producir, con extraordinarios

altos niveles de destreza, ya sea digital

o a mano. Qued muy impresionado por

los dibujos de este catlogo y aunque

eran principalmente dibujos de diseo,

todos ellos sugeran, de un modo claro

el sistema de construccin, intuido en la

manera en que estaban dibujados. To-

dava hoy, creo que esta habilidad per-

manece en la cultura arquitectnica es-

paola, donde el diseo y la construccin

no son fases separadas.

e

x

p

r

e

s

i

n

g

r

f

i

c

a

a

r

q

u

i

t

e

c

t

n

i

c

a

conversando con KENNETH FRAMPTON

L.L.: Estamos hablando de la expresin ar-

quitectnica como nica en cada pas, re-

gin o escuela. Mientras que cada escue-

la de arquitectura y cada arquitecto encuen-

tren su personal y diferenciada forma de

expresin grfica, surge, una vez ms, la

amenaza de la tcnica y de la globalizacin.

Cul es su opinin sobre el hecho de que

esta rica variedad grfica pueda resultar

amenazada por la tecnologa, la transmi-

sin de datos y la globalizacin? Cmo

se relaciona esta realidad con el concep-

to del relativismo cultural? Existen este

tipo de diferencias entre la enseanza de

los Estados Unidos y Europa?

K.F.: Esto, obviamente, se relaciona con

su pregunta anterior y mi respuesta es

ms o menos la misma. Tal vez sea po-

sible relacionar esto con el concepto del

regionalismo crtico como apareci

en mi ensayo de 1983 Hacia un regio-

nalismo crtico: seis puntos hacia una ar-

quitectura de resistencia. Y estoy muy

en deuda en este asunto con Alexander

Tzonis y Liane Lefaivre, quienes en su

ensayo de 1981 titulado The grid and

the pathway acuaron el trmino re-

gionalismo crtico. Uno de los argumen-

tos que utilizo en mi elaboracin de es-

ta idea es la necesidad de poder usar

tecnologa universal de modo que se con-

jugue con un momento y un lugar deter-

minado. Hay muchos factores implica-

dos en esto como la topografa, el clima,

los materiales, la habilidad de la mano

de obra local, e incluso los modos de

comportamiento tradicionales, etc. s-

tos todava difieren algo de un sitio a

otro. De ah la crucial importancia del

lugar, la topografa y la manera en que

esto pueda afectar a la obra construida.

Encuentro interesante que slo recien-

temente haya aparecido la profesin de

arquitecto paisajista en Espaa, ya que

hasta ahora, los arquitectos trabajaban

tambin como paisajistas. El trabajo en

Espaa a menudo muestra actitudes ex-

traordinariamente sensibles hacia el sue-

lo y el terreno.

32 surely a cultural and conceptual aporia and yet it

remains a fact that it is still possible to teach

people to put ideas down on paper, ad hoc. It is

not a matter of resisting or replacing the digital,

but rather a matter of amplifying its capacity.

Renzo Piano once said to me that in his office in

Genoa he insisted that the project constantly

passes through three points: drawing by hand,

digital drafting, and the making of models, and

that this triad was followed at every stage of the

project constantly circulating through these

three points. Such an approach adheres, like

Scarpa, to the notion that architecture in the last

analysis is a craft rather than an art or a science.

One may still sense a vestige of this in the latest

productive capacity of any country. One has the

illusion that technological capacity is the same

the entire world over but often in actual practice

one encounters subtle differences such as when

one compares, for example, welded steel in

Germany to same performance in the American

building industry.

L.L.: Professor Frampton, previously you made a

comment about the quality and sensitivity of

Spanish drawings both in the universities as

well as in different mass media publications.

What graphic differences do you find unique in

the scene of the Spanish graphic architecture in

relation to other countries or universities such as

the GSAPP?

K.F.: I am of the opinion that there remains three

absolutely exceptional European schools of

architecture: the Royal Academy in Copenhagen,

the ESTA School of Architecture in Madrid, and

the Department of Architecture in the Helsinki

Technical University. Architects being trained in

these schools were once expected and are still

even now expected to be capable of integrating

detailed technique with the design of built form,

so that there is no split between the capacity to

build and the capacity to design. The curriculum

in these three schools used to refuse to accept

that there was any kind of inherent split

between these aspects of being an architect.

This was until recently a big strength in the

Spanish architectural education although I am

aware that the Bologna Agreement in seeking to

regularize and to deregulate architectural

practice all over Europe is actually a direct threat

to this exceptionally high professional

educational standard, along with the progressive

dissolution of the Colegio de Arquitectos de

L.L.: Mi ltima pregunta est relaciona-

da con una cuestin, que en cierto modo

preocupa a un gran nmero de arquitec-

tos dedicados a la docencia, lo que podra-

mos denominar arquitecto terico de es-

cuela. Mientras que en los Estados

Unidos la mayor parte de los profesores

de diseo son crticos o tericos en Espa-

a, tradicionalmente, compaginaban la

docencia con sus despachos de arquitec-

tura. Actualmente en Espaa esta toman-

do fuerza el papel del arquitecto como in-

vestigador y para ser profesor debes

cumplimentar una carrera investigadora

muy rigurosa y tener en tu haber una te-

sis doctoral, Cree que esto es una bue-

na prctica o por el contrario opina que

esta regulacin va en contra de la labor

principal del arquitecto: dibujar, proyec-

tar y construir? Cree que se corre el ries-

go de perderse la prctica del dibujo por

una excesiva dedicacin a cumplimentar

requerimientos acadmicos?

K.F.: Esta pregunta me recuerda un afo-

rismo de lvaro Siza en que deca: Les

digo (al universo de autoridades) que un

arquitecto es un especialista en la no es-

pecializacin, pero ni siquiera lo pueden

tomar como una broma. Este aforismo

resume el contexto de tu pregunta; en

este aspecto la arquitectura es una pro-

fesin reciente. Esto significa que la ar-

quitectura est situada, de un modo in-

cmodo, dentro de la Universidad. El

deseo por parte de la Universidad de con-

vertir ciertos campos pragmticos en aca-

dmicos es una especie de perversin ins-

titucional. Esto es como la reciente moda

de establecer programas de doctorado

en Bellas Artes; no en historia del arte

sino en la prctica del arte. Cuando

dije que la arquitectura es en ltima ins-

tancia un oficio, tambin est implcita

la nocin del proceso en el que apren-

des el oficio trabajando con un maestro,

que sola ser un prerrequisito para los

estudios de arquitectura en Espaa, la

costumbre de tener arquitectos en acti-

vo como profesores. Esto reconoce la ar-

quitectura como un oficio. Incluso aho-

ra est implcito que los profesores de

arquitectura debieran ser arquitectos en

ejercicio. Y la corriente actual, que es in-

sistir en ser doctor, desde mi punto de

vista, una regresin impulsada en la Uni-

versidad por la investigacin cientfica.

La idea fundada en que un arquitecto no

slo tiene la habilidad para disear edi-

ficios sino que tambin es un cultivado

intelectual, est muy lejos de la idea del

arquitecto en el mundo moderno anglo-

estadounidense. En Italia era normal,

hasta hace poco, que un arquitecto en

ejercicio tambin fuera una persona aca-

dmica y tericamente cultivada. Rafael

Moneo, por ejemplo, es un producto cla-

ro de esa cultura. Por ello, creo que su

pregunta, en cierto modo, apunta a es-

te cisma y es tambin, de nuevo, una

consecuencia del Proceso de Bolonia. As

que en relacin a su pregunta sobre si

los arquitectos corren el peligro de per-

der su prctica, es un hecho que los j-

venes arquitectos inteligentes, como us-

ted, se ven atrapados en el crculo

acadmico quieran o no. Son menos ca-

paces de desarrollar un estudio porque

son parte de un sistema burocrtico. Es-

ta dificultad de mantener un equilibrio

es algo de lo que debiramos ser cons-

cientes. Esta obsesin con los doctora-

dos es desafortunada pero ahora es par-

te del escenario. Espero que obres el

milagro de hacer ambas cosas.

Muchas gracias Profesor Frampton.

NOTAS

1 / Escuela de Estudios Medioambientales.

Traducido por Nacho Cabodevilla

33

e

x

p

r

e

s

i

n

g

r

f

i

c

a

a

r

q

u

i

t

e

c

t

n

i

c

a

conversando con KENNETH FRAMPTON

Espaa. I know what it used to take on average

eight years for architects to graduate in Spain,

but the EC wishes to make this much shorter.

This is part of a relatively long-standing late

capitalistic policy to deregulate professions, so

one can obtain the professional services much

cheaper. Judging from a recent publication by

the Spanish Ministry of Public Works serving as

a catalogue for an exhibition of young Spanish

architects there still remains a capacity to

produce remarkably high levels of craftsmanship

in Spain, whether digital or by hand. I was very

impressed by the drawings in this catalogue and

even though they were mainly design drawings,

they nonetheless clearly implied the mode of

construction in the way in which they were

drawn. Still now, I think this capacity remains in

Spanish architectural culture where design and

construction are not separate phases.

L.L.: The expression of architecture is unique to

each country, region or university. Each

architectural school and each architect have

their own individual way of graphic expression.

Modern technology and globalization can be a

threat to this individual expression. What is your

opinion on this concept of the threat of modern

technology, data transmission and globalization

to the quality and uniqueness of architectural

expression? How is this related to the concept of

cultural relativism? Do these kinds of differences

exist between how architecture is taught in the

United States versus Europe?

K.F.:This obviously directly relates to your

previous question and my reply is more or less the

same. It is perhaps possible to relate this to the

concept of critical regionalism as this appeared

in my 1983 essay Towards a Critical

Regionalism: Six Points Towards an Architecture

of Resistance. And I am very indebted in this

regard to Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre

who in their 1981 essay entitled: The Grid and

the Pathway first coined the term critical

regionalism. One of the arguments I make in my

elaboration of this idea is the necessity of being

able to use universal technology in such a way as

to inflect it in relation to a particular place and a

particular time. Many factors are involved in this

such as topography, climate, materials, local craft

capacity, and even traditional modes of behaviors,

etc. These still differ somewhat from one place to

another. Thus the crucial importance of the site

and the topography and the way in which this

may already inflect the built work.

I find it interesting that only recently has there

been a profession of landscape architecture in

Spain, that up to now, architects, served

landscape architects. Spanish work often

displays rather remarkably sensitive attitudes

towards the ground and the land.

L.L.: My last question concerns the topic of the

role of the professor of architecture, which we

could refer to as the theoretical professor. I

notice that in the United States the majority of

architectural projects professors are either

critics or theorists. In contrast, in Spain,

professors have traditionally been working

architects with their own design studios and

actual projects. As of late, the Spanish

Universities have changed their guidelines and

now professors of architecture must complete a

rigorous research career and have doctorate

degree. Do you think this is a good practice or,

on the other hand, do these regulations

decrease the main skills of the architects, which

are drawing, designing and building? Do you

think that architectural lecturers spend more

time meeting academic requirements than being

architects?

K.F.: This question reminds me of an aphorism

about Alvaro Siza in which he said: I tell them

(the universe of authorities) that an architect is a

specialist in non-specialization, but they cannot

take that not even as a joke. This aphorism

sums up for me the context of your question in

this regard architecture is a relatively late

profession. This means that architecture is

situated rather uncomfortably within the

University. The desire on the part of the

university to make certain synthetic pragmatic

fields academic is a kind of institutional

perversion. This is like the recent fashion of

establishing PhD programs in Fine Arts; not art

history but in the practice of art. When I spoke

about architecture being ultimately a craft, there

is also implied the notion of apprenticeship

wherein one acquires the craft from working

with a master that used to be a pre-requisite for

studio instructors in architecture in Spain, the

habit that is of having practicing architects as

professors of architecture. This already

acknowledges architecture as a craft. It is still

implicit even now that the professors of

architecture should be practicing architects. And

the current move, which is to insist on a PhD is

already, in my view, a regression driven forward

in the university by the research of science.

The idea that an architect would not only have

the capacity to design buildings but would also

be a cultivated intellectual is very far from the

idea of the architect in he late modern Anglo-

American world. In Italy it was until late normal

that a practicing architect would also be a

cultivated person academically and theoretically.

Rafael Moneo, for example, is very much a

product of such a culture. So I think your

question points to this schism in a way and is

also once again a by-product of the Bologna

Agreement. So regarding your question as to

whether studio instructors run the risk of losing

their practice, it is just a fact that young

intelligent architects, like yourself, are caught in

the academic mill whether they like it or not.

They are less able to develop a practice because

they are part of a bureaucratic system. This

difficulty of maintaining a balance is something

that we should be aware of. This obsession with

PhD degrees is unfortunate but it is by now part

of the territory. One hopes that you will pull of

the trick of doing both.

Thank you so much Professor Frampton.

Translation by Nacho Cabodevilla

You might also like

- (Architecture Ebook) Architectural Thought - The Design Process and The Expectant EyeDocument191 pages(Architecture Ebook) Architectural Thought - The Design Process and The Expectant EyeMike Sathorar100% (3)

- Studies in Tectonic CultureDocument446 pagesStudies in Tectonic CultureTeerawee Jira-kul100% (29)

- Farrah, S., Representation As QuotationDocument12 pagesFarrah, S., Representation As QuotationMax MinNo ratings yet

- Expressionist Architecture: School of Architecture and PlanningDocument7 pagesExpressionist Architecture: School of Architecture and PlanningPavithra ValluvanNo ratings yet

- Theory of Architecture-Ii: Batch 2020, Pes FoaDocument8 pagesTheory of Architecture-Ii: Batch 2020, Pes FoaYOGITH B NAIDU YOGITH B NAIDUNo ratings yet

- Graphic Design in The Postmodern EraDocument7 pagesGraphic Design in The Postmodern EradiarysapoNo ratings yet

- Summerson PDFDocument11 pagesSummerson PDFJulianMaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Ideas That Shaped BuildingsDocument373 pagesIdeas That Shaped BuildingsLiana Wahyudi100% (13)

- Kenneth Frampton - John Cava - Studies in Tectonic Culture - The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture-MIT Press (2001) PDFDocument447 pagesKenneth Frampton - John Cava - Studies in Tectonic Culture - The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture-MIT Press (2001) PDFLaura KrebsNo ratings yet

- 2020 Student Project Hybrid KrakovskaDocument4 pages2020 Student Project Hybrid KrakovskaBeMyGuest ÉvoraNo ratings yet

- Notes On Utopia, The City, and Architecture: Grey Room September 2017Document13 pagesNotes On Utopia, The City, and Architecture: Grey Room September 2017Gëzim IslamajNo ratings yet

- Frampton Studies in Tectonic Culture 1995 P 1 12 Email PDFDocument14 pagesFrampton Studies in Tectonic Culture 1995 P 1 12 Email PDFviharlanyaNo ratings yet

- Presence of Mies (Art Essay Architecture) PDFDocument274 pagesPresence of Mies (Art Essay Architecture) PDFRodrigo Alcocer100% (3)

- Arquitectura BritanicaDocument306 pagesArquitectura BritanicaErmitañoDelValleNo ratings yet

- Tom Avermaete Voir Grille CIAM AlgerDocument15 pagesTom Avermaete Voir Grille CIAM AlgerNabila Stam StamNo ratings yet

- Architectural Principles in The Age of FDocument29 pagesArchitectural Principles in The Age of Fjmmoca100% (1)

- Running Heading: Architecture Influencing Art Forms 1Document26 pagesRunning Heading: Architecture Influencing Art Forms 1sakethNo ratings yet

- Towards an anthropological theory of architecture: Eliminating the gap between society and architectureDocument18 pagesTowards an anthropological theory of architecture: Eliminating the gap between society and architectureEvie McKenzieNo ratings yet

- n07 113 JohnsonDocument16 pagesn07 113 JohnsonAnisha TrisalNo ratings yet

- What Architects Do With Philosophy Three Case StudDocument18 pagesWhat Architects Do With Philosophy Three Case Studfatima medinaNo ratings yet

- White Ley 1990Document35 pagesWhite Ley 1990Erdem KaraçayNo ratings yet

- RadicalityDocument7 pagesRadicalityAlaa RamziNo ratings yet

- Architectural exhibitions as agents of changeDocument5 pagesArchitectural exhibitions as agents of changeGözde Damla TurhanNo ratings yet

- Zaha HadidDocument12 pagesZaha HadidQuangVietNhatNguyenNo ratings yet

- Research For Research - Bart LootsmaDocument4 pagesResearch For Research - Bart LootsmaliviaNo ratings yet

- Theory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDocument28 pagesTheory of Architecture (Toa) : Name SRNDhanush KeshavNo ratings yet

- Studies in Tectonic Culture PDFDocument14 pagesStudies in Tectonic Culture PDFF ANo ratings yet

- Reyner Banham and Rem Koolhaas, Critical ThinkingDocument4 pagesReyner Banham and Rem Koolhaas, Critical ThinkingAsa DarmatriajiNo ratings yet

- Megaform As Urban Landscape: Kenneth FramptonDocument25 pagesMegaform As Urban Landscape: Kenneth FramptonMeche AlvariñoNo ratings yet

- Typo Logical Process and Design TheoryDocument178 pagesTypo Logical Process and Design TheoryN Shravan Kumar100% (3)

- PARNELL Steve, Post-Truth ArchitectureDocument8 pagesPARNELL Steve, Post-Truth Architectureyasmine.k.hassaniNo ratings yet

- Christoph Gantenbein2Document5 pagesChristoph Gantenbein2Häuser TrigoNo ratings yet

- To Remember PostmodernismDocument8 pagesTo Remember PostmodernismSelverNo ratings yet

- About How Eisenman Use DiagramDocument7 pagesAbout How Eisenman Use DiagramPang Benjawan0% (1)

- Four Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple ProfessionFrom EverandFour Walls and a Roof: The Complex Nature of a Simple ProfessionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Reconnecting Practice and MeaningDocument7 pagesReconnecting Practice and MeaningNebojsaNo ratings yet

- The Fashion (Ing) of ArchitectureDocument11 pagesThe Fashion (Ing) of ArchitectureScott SwortsNo ratings yet

- Convention CenterDocument71 pagesConvention CenterJosette Mae AtanacioNo ratings yet

- Computing Without ComputersDocument10 pagesComputing Without ComputersHülya OralNo ratings yet

- Reading Kenneth Frampton: A Commentary on 'Modern Architecture', 1980From EverandReading Kenneth Frampton: A Commentary on 'Modern Architecture', 1980No ratings yet

- Building Ideas - An Introduction To Architectural TheoryDocument250 pagesBuilding Ideas - An Introduction To Architectural TheoryRaluca Gîlcă100% (2)

- Postmodernism & ArchitectureDocument6 pagesPostmodernism & ArchitecturenicktubachNo ratings yet

- Theories and History of Architecture - Manfredo Tafuri PDFDocument342 pagesTheories and History of Architecture - Manfredo Tafuri PDFshuvit90100% (3)

- POST Modern Theory 2Document41 pagesPOST Modern Theory 2Madhuri GulabaniNo ratings yet

- Behind The Postmodern FacadeDocument228 pagesBehind The Postmodern FacadeCarlo CayabaNo ratings yet

- Visuality for Architects: Architectural Creativity and Modern Theories of Perception and ImaginationFrom EverandVisuality for Architects: Architectural Creativity and Modern Theories of Perception and ImaginationNo ratings yet

- Brutal London: A Photographic Exploration of Post-War LondonFrom EverandBrutal London: A Photographic Exploration of Post-War LondonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Bauhaus Ideal Then and Now: An Illustrated Guide to Modern DesignFrom EverandThe Bauhaus Ideal Then and Now: An Illustrated Guide to Modern DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- How Architecture Works: A Humanist's ToolkitFrom EverandHow Architecture Works: A Humanist's ToolkitRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Dimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge: Vol. 2, No. 4/2022: Essentials of Montage in ArchitectureFrom EverandDimensions. Journal of Architectural Knowledge: Vol. 2, No. 4/2022: Essentials of Montage in ArchitectureMax TreiberNo ratings yet

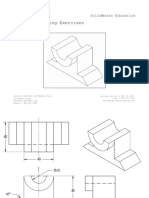

- SolidWorks Education Detailed Drawing ExercisesDocument51 pagesSolidWorks Education Detailed Drawing ExercisesLal Krrish MikeNo ratings yet

- List of ArchitectsDocument6 pagesList of ArchitectsSujash GhoshNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6-Project Delivery MethodsDocument37 pagesLecture 6-Project Delivery MethodsKinfe MehariNo ratings yet

- Operations - ManagementDocument30 pagesOperations - ManagementShabitha SumanathasaNo ratings yet

- NOTA 8 The Instructional Design of Learning ObjectsDocument8 pagesNOTA 8 The Instructional Design of Learning ObjectsMuney KikiNo ratings yet

- Basic of Timing Analysis in Physical Design - VLSI ConceptsDocument5 pagesBasic of Timing Analysis in Physical Design - VLSI ConceptsIlaiyaveni IyanduraiNo ratings yet

- Facility or Layout PlanningDocument12 pagesFacility or Layout PlanningsNo ratings yet

- Ten Steps To Complex LearningDocument6 pagesTen Steps To Complex LearningAgus RahardjaNo ratings yet

- Reubens TrophyDocument3 pagesReubens TrophyAntriksh RathiNo ratings yet

- Shangai Natural MuseumDocument6 pagesShangai Natural MuseumLjubica TrkuljaNo ratings yet

- IIIDaward Poster 2020 PDocument2 pagesIIIDaward Poster 2020 PAmerika Sánchez LeónNo ratings yet

- Performance-Based and Performance-Driven Architectural Design and OptimizationDocument7 pagesPerformance-Based and Performance-Driven Architectural Design and OptimizationInas AbdelsabourNo ratings yet

- Manuale - Lavapadelle - Atos - Af2-60 (Lista Ricambi) - Service - ItDocument108 pagesManuale - Lavapadelle - Atos - Af2-60 (Lista Ricambi) - Service - ItVitor FilipeNo ratings yet

- Provincial Road Management Facility: External Review ReportDocument42 pagesProvincial Road Management Facility: External Review ReportClaire Duhaylungsod AradoNo ratings yet

- 2023 GR 11 Design June Exam Theory ExamDocument26 pages2023 GR 11 Design June Exam Theory Examiris.hossansNo ratings yet

- KMSLCDocument28 pagesKMSLCVishal VarshneyNo ratings yet

- IJuanderer An Augmented Reality-Based Gamified Local Tourism and Cultural Heritage Promotion and PreservationDocument12 pagesIJuanderer An Augmented Reality-Based Gamified Local Tourism and Cultural Heritage Promotion and PreservationIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- CSS3 PropertiesDocument1 pageCSS3 PropertiesSubbu tNo ratings yet

- DC - Unit VI - ASVDocument52 pagesDC - Unit VI - ASVAnup S. Vibhute DITNo ratings yet

- Formalighting PDFDocument222 pagesFormalighting PDFJESUS MIGUEL APAZA ARISACANo ratings yet

- CIM Analysis of Automated Flow LinesDocument48 pagesCIM Analysis of Automated Flow LinesvrushNo ratings yet

- Archived: Interior Design GuideDocument38 pagesArchived: Interior Design GuideNEWS 2DAYNo ratings yet

- OBE Method of Assessments For Capstone Civil Engineering Project DesignDocument18 pagesOBE Method of Assessments For Capstone Civil Engineering Project DesignMd. Basir ZisanNo ratings yet

- MEMS Design and AnalysisDocument9 pagesMEMS Design and Analysisjanderson13No ratings yet

- DTK Det DepDocument49 pagesDTK Det DepJames SmithNo ratings yet

- Amidds - Architectural - Building Congres PDFDocument413 pagesAmidds - Architectural - Building Congres PDFdelciogarciaNo ratings yet

- NCO Important Questions Class 2Document12 pagesNCO Important Questions Class 2Bimal DeyNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Digital System Design Using Verilog HDLDocument51 pagesIntroduction to Digital System Design Using Verilog HDLsft007No ratings yet

- Quality Engineering / Technical Quality: NotesDocument20 pagesQuality Engineering / Technical Quality: NotesMuhammad Zain NawwarNo ratings yet

- PowerPointHub Monk Gx2vH5Document44 pagesPowerPointHub Monk Gx2vH5Alisson MuñozNo ratings yet