Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisweeqe PDF

Uploaded by

sharu42910 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views3 pages44922159-ABC-Emergency-Differential-Diagnosisweeqe.pdf

Original Title

44922159-ABC-Emergency-Differential-Diagnosisweeqe.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document44922159-ABC-Emergency-Differential-Diagnosisweeqe.pdf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views3 pagesABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisweeqe PDF

Uploaded by

sharu429144922159-ABC-Emergency-Differential-Diagnosisweeqe.pdf

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

50 ABC of Emergency Differential Diagnosis

Acute thiamine deciency

Chronic alcohol use, particularly when associated with

malnutrition, can cause vitamin B1 (thiamine) deciency.

Thiamine deciency causes damage to the mamillary bodies,

cranial nerve nuclei, thalamus and cerebellum, termed Wernickes

encephalopathy, a triad of:

Encephalopathy (disorientation, agitation, indifference and 1

inattentiveness, short term memory loss)

Occulomotor disturbance (nystagmus, lateral rectus palsy) 2

Ataxic gait 3

To diagnose Wernickes encephalopathy, however, it is not necessary

to have all three components present.

To protect against Wernickes encephalopathy intravenous

thiamine should be administered to any patient who is confused,

with a history of alcohol abuse. If the blood sugar is also low, it

is important to administer glucose with the thiamine treatment.

If Wernickes encephalopathy is not treated the confusion is liable

to progress to stupor or death.

Korsakoff s psychosis is a late neuropsychiatric manifestation

of Wernickes encephalopathy. It is characterised by confusion,

confabulation and amnesia (anterograde and retrograde). The

memory problems associated with Korsakoff s syndrome are largely

irreversible.

Acute alcohol intoxication

Alcohol affects the brain like an anaesthetic. The effects of alcohol

depend on the amount ingested (see Table 12.5).

Measuring the serum alcohol level has limited use it conrms

approximately how much alcohol has been ingested but does not

exclude other important causes which may co-exist.

This diagnosis is not suggested by the history.

Alcoholic ketosis

This is an acute metabolic acidosis that typically occurs in people

who chronically abuse alcohol and have a recent history of binge

drinking, little or no food intake, and persistent vomiting.

Patients typically present with nausea, vomiting and abdominal

pain. They are usually hypotensive, tachycardic and tachypnoeic

with the fruity odour of ketones present on their breath. They

are usually alert and lucid, but may have mild confusion.

Investigations show a raised anion gap metabolic acidosis, with

normal lactate and raised serum and urine ketone levels.

Systemic infections

People with chronic alcohol dependence are relatively immuno-

compromised, malnourished and more commonly exposed

to infectious agents (e.g. tuberculosis) than others. Infections,

in particular of the nervous system, e.g. meningitis, encephalitis,

can present with non-specic confusion and vomiting.

Case history revisited

Revisiting the case, the diagnosis is not immediately obvious. This

man regularly drinks excessive amounts of alcohol and presents

more than 12 hours after ingesting a large amount of alcohol. This

late presentation would not be typical for a presentation of acute

alcohol intoxication.

On examination, his Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) is 14/15 (E4,

M6, V4) he is confused and disorientated to time and person.

His observations are: blood pressure 160/100 mmHg, pulse

120 beats/minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths/minute and blood

glucose (meter) 4.5 mmol. He appears sweaty and is irritable, but

allows you to perform a limited examination.

Box 12.2 NICE guidelines indications for urgent CT head scan

in head injuries.

GCS <13 on initial assessment in the Emergency Department

GCS <15 when assessed in the Emergency Department 2 hours

post injury

Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

Any sign of basal skull fracture haemotympanum, panda

eyes, cerebrospinal uid leakage from ears or nose, Battles sign

(bruising to the mastoid area)

Post-traumatic seizure

Focal neurological defect

>1 episode of vomiting

Amnesia or loss of consciousness and coagulopathy

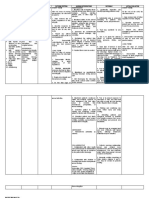

Table 12.5 Effects of acute alcohol ingestion.

Stage Effect

Euphoria Overall improvement in mood, becoming more self-condent

and daring. Attention span shortens and judgement becomes

impaired

Lethargy Sleepiness, difculty understanding or remembering things.

Reactions slow and body movements become uncoordinated

Confusion Profound confusion, disorientation, heightened emotional

state aggression, withdrawal or overly affectionate. Nausea

and vomiting

Stupor GCS uctuates between 3 and 13

Coma GCS 3/15, pupil reexes to light diminished, pulse and

respiratory rate lowers

The Intoxicated Patient 51

He has a 4 cm cut to his forehead (partial thickness) with some

surrounding swelling, but no bogginess. He has no post-auric-

ular bruising, haemotympanum, panda eyes or evidence of a

cerebrospinal uid leak.

He has slurred speech and a tremor at rest. Peripheral nervous

system examination reveals normal power, tone, reexes and sensa-

tion but coordination is impaired with dysdiadokinesia. Nystagmus

is noted on eye examination, otherwise cranial nerves are intact.

Whilst you are examining him he appears to be becoming more

agitated. He is pulling at the sheets and grabbing out at the air

periodically and is becoming less cooperative.

Question: Given the history and

examination ndings what is your

principal working diagnosis?

Principal working diagnosis Acute alcohol

withdrawal though one needs to exclude

intracranial pathology and acute thiamine

deciency

The most likely diagnosis for this patient is acute alcohol with-

drawal. He is sweaty and tachycardic, has a tremor and is becoming

increasingly agitated. Pulling at his sheets and grabbing at the air

may be signs of the agitation or of visual hallucinations associated

with the withdrawal.

As previously discussed, it is very important not to miss head

injuries in this group of patients that are notoriously difcult to

assess. If there are signs of a head injury in these patients, brain

imaging should be considered.

This patient also has signs of possible encephalopathy and the eye

signs (nystagmus) could be related to the excess alcohol but could

also be a sign of Wernickes encephalopathy. He should be treated for

possible acute thiamine deciency in addition to the withdrawal, as

this could progress if left untreated, with disastrous results.

Management

This man requires close observation, intravenous thiamine,

treatment for alcohol withdrawal (lorazepam/chlordiazepoxide)

and a CT scan to exclude intracerebral pathology.

Outcome

His CT/head scan was normal and his agitation and confusion

settled with regular thiamine and chlordiazepoxide.

Further reading

Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford Handbook of General Practice, Second

Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2002.

Tintinalli J, Kelen G, Stapczynski S, et al. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive

Study Guide. Sixth Edition. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2003.

Wyatt JP, Illingworth R, Graham C, et al. Oxford Handbook of Emergency

Medicine, Third Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006.

A blood glucose meter.

52

CHAPTER 13

The Shocked Patient

Arun Chaudhuri

ABC of Emergency Differential Diagnosis. Edited by F. Morris and A. Fletcher.

2009 Blackwell Publishing, ISBN: 978-1-4051-7063-5.

Question: What differential diagnosis

would you consider from the history?

Shock arises from an inadequate ow of blood to organs and tissues:

the result is organ dysfunction (see Figure 13.1 and Box 13.1).

There are three broad types of shock (see Box 13.2) from which

four subtypes merit careful consideration in this case.

Septic shock

This form of shock is caused by the systemic response to a severe

infection. Identifying the systemic response (systemic inammatory

response syndrome: SIRS) is extremely important so that appropri-

ate management can be started early: all frontline healthcare pro-

fessionals should be familiar with diagnosing sepsis (see Box 13.3).

Septic shock occurs most frequently in elderly (65 years),

immunocompromised patients, or those who have undergone an

invasive procedure in which there is high chance of bacteraemia.

Infection of the lungs, abdomen or urinary tract is most com-

mon. Micro-organisms such as Gram-positive and Gram-negative

bacteria, viruses, fungi, rickettsiae and protozoa can all produce

septic shock. Systemic infection and toxins released by the

infectious organisms produce interleukins leading to metabolic and

circulatory derangement.

Haemodynamic changes in septic shock occur in two charac-

teristic patterns: early or hyperdynamic, and late or hypodynamic

septic shock. In hyperdynamic septic shock the extremities are

usually warm. Total oxygen delivery may be increased while oxy-

gen extraction is reduced leading to cellular hypoxia. As sepsis

progresses, hypodynamic shock develops leading to vasoconstric-

tion and reduced cardiac output. The patient usually becomes

markedly breathless, febrile and sweaty with cool, mottled and

often cyanotic peripheries. Multiple organ failure develops with a

striking increase in serum lactate. The mortality from septic shock

remains staggeringly high; approximately 3540% of patients die

within 1 month of onset of septic shock.

Hypovolaemic shock

This most common form of shock, results either from the loss of

red blood cell mass and plasma from haemorrhage or from loss of

plasma volume alone arising from extravascular uid sequestration

or gastrointestinal, urinary and insensible losses. Hypovolaemic

shock is usually diagnosed easily if the source of volume loss is

obvious, but the diagnosis can be extremely difcult if the source

is occult, such as into the gastrointestinal tract. In the latter case,

a history of non-steroidal anti-inammatory use, dark sticky stool

(melaena), and upper abdominal pain is helpful. A rectal examina-

tion is mandatory to detect occult melaena.

Mild hypovolaemia (15% loss of the blood volume) pro-

duces mild tachycardia without any external signs, especially in a

supine resting adult patient. With moderate hypovolaemia (loss of

1530% of blood volume) the patient will have signicant postural

hypotension and tachycardia despite normal supine blood pressure,

although the pulse pressure will be reduced.

Classic signs of shock appear if hypovolaemia is severe (30%

loss of the blood volume). The patient develops marked tachy-

cardia, supine hypotension, oliguria, and agitation or confusion,

progressing to coma. The transition from mild to severe hypovo-

laemic shock can be insidious or extremely rapid. If severe shock

is not reversed rapidly, especially in elderly patients and those

with multiple comorbidities, it can lead to ischaemic injury and to

irreversible decline.

CASE HISTORY

A 68-year-old woman rapidly develops severe breathlessness,

clamminess and agitation. She was well 2 days ago, when a

non-productive cough and a fever began. The symptoms have

progressed since then and become much worse today with

intermittent drowsiness and mottling of her skin. She has no chest

pain or wheeze, but her husband noticed she has not passed

much urine lately and that she looks much paler today with cold

hands and feet. She consulted her GP yesterday who thought she

had a viral upper respiratory tract infection. She took some

over-the-counter u remedy tablets this morning. She has a past

history of ischaemic heart disease, hypertension and type 2

diabetes mellitus. She has never smoked and there is no history of

chronic obstructive airway disease or bronchial asthma. Recently

she enjoyed a wonderful holiday in Greece and returned 3 days

ago. Her medication includes aspirin, bisoprolol, isosorbide

mononitrate SR, irbesartan, gliclazide and metformin. She is a

retired nurse and lives independently with her husband.

You might also like

- Conduct Rule GazetteDocument1 pageConduct Rule Gazettesharu4291No ratings yet

- TFCO Healthy Food in SchoolsDocument12 pagesTFCO Healthy Food in Schoolssharu4291No ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu State Services Rules SummaryDocument100 pagesTamil Nadu State Services Rules SummaryJoswa Santhakumar100% (1)

- Comparison CarsDocument5 pagesComparison Carssharu4291No ratings yet

- Healthy EatingDocument2 pagesHealthy Eatingsharu4291No ratings yet

- Renal Urology HistoryDocument131 pagesRenal Urology Historysharu4291No ratings yet

- UW Path NoteDocument218 pagesUW Path NoteSophia Yin100% (4)

- Healthy Eating PlannerDocument10 pagesHealthy Eating Plannerjasdfl asdlfjNo ratings yet

- Compliance HandBook FY 2015-16Document32 pagesCompliance HandBook FY 2015-16sunru24No ratings yet

- Neeraj S Notes Step3Document0 pagesNeeraj S Notes Step3Mrudula Rao100% (1)

- Hospitals and Healthy FoodDocument8 pagesHospitals and Healthy Foodsharu4291No ratings yet

- Molecules 18 08976Document18 pagesMolecules 18 08976sharu4291No ratings yet

- Usmle Hy Step1Document20 pagesUsmle Hy Step1Sindu SaiNo ratings yet

- Estado Hiperosmolar HiperglucemicoDocument8 pagesEstado Hiperosmolar HiperglucemicoMel BlancaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: BackgroundDocument2 pagesChapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Backgroundsharu4291No ratings yet

- T - Nadu Govt Servants Conduct RulesDocument42 pagesT - Nadu Govt Servants Conduct Rulessharu4291No ratings yet

- ChoiDocument19 pagesChoiLuciana RafaelNo ratings yet

- Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome: R. Venkatraman and Sunit C. SinghiDocument6 pagesHyperglycemic Hyperosmolar Nonketotic Syndrome: R. Venkatraman and Sunit C. Singhisharu4291No ratings yet

- Asymptomatic Hyperuricemia: To Treat or Not To Treat: ReviewDocument8 pagesAsymptomatic Hyperuricemia: To Treat or Not To Treat: ReviewkkichaNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGDocument7 pagesApproach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGsharu4291No ratings yet

- Disorders of Nucleotide Metabolism: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Uric AcidDocument9 pagesDisorders of Nucleotide Metabolism: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Uric AcidSaaqo QasimNo ratings yet

- Prospectus MDMSJULY2015Document39 pagesProspectus MDMSJULY2015sharu4291No ratings yet

- Chapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: BackgroundDocument2 pagesChapter 23: Hyperuricemia and Gout: Backgroundsharu4291No ratings yet

- Approach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGDocument7 pagesApproach To A Case of Hyperuricemia: Singh V, Gomez VV, Swamy SGsharu4291No ratings yet

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisbbxc PDFDocument3 pagesABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisbbxc PDFsharu4291No ratings yet

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisssbbfvvcv PDFDocument3 pagesABC Emergency Differential Diagnosisssbbfvvcv PDFsharu4291No ratings yet

- Acute Alcohol WithdrawalDocument3 pagesAcute Alcohol Withdrawalsharu4291No ratings yet

- ABC Emergency Differential Diagnosissssv PDFDocument3 pagesABC Emergency Differential Diagnosissssv PDFsharu4291No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Ian Caplar - Depressive Disorders Powerpoint 1Document23 pagesIan Caplar - Depressive Disorders Powerpoint 1api-314113064No ratings yet

- DacryocystorhinostomyDocument3 pagesDacryocystorhinostomyNarla SusheelNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of Trigeminal Nerve & Trigeminal Neuralgia: Presented By: DR - Vansh Vardhan Madahar PG1 YearDocument47 pagesAnatomy of Trigeminal Nerve & Trigeminal Neuralgia: Presented By: DR - Vansh Vardhan Madahar PG1 YearVansh Vardhan MadaharNo ratings yet

- CHAP 21 - Immediate Loading of Dental Implants PDFDocument15 pagesCHAP 21 - Immediate Loading of Dental Implants PDFYassin SalahNo ratings yet

- Endoscope Disinfection by SosDocument12 pagesEndoscope Disinfection by SosSimran BajajNo ratings yet

- Anu Omr Long CaseDocument29 pagesAnu Omr Long CaseAnurtha AnuNo ratings yet

- Lifeline Health Insurance Plans GuideDocument5 pagesLifeline Health Insurance Plans GuideSumit BhandariNo ratings yet

- NCP Systemic Viral Infection SVIDocument4 pagesNCP Systemic Viral Infection SVIPavel Kolesnikov100% (1)

- NSAIDS ComparisonDocument60 pagesNSAIDS ComparisonsillymajorNo ratings yet

- MKSAP 18 Infectious DiseaseDocument206 pagesMKSAP 18 Infectious Diseasemus100% (2)

- Nursing Oncology CourseworkDocument6 pagesNursing Oncology Courseworkafjwftijfbwmen100% (2)

- Overview of Hiccup Study DetailsDocument4 pagesOverview of Hiccup Study DetailsphreonburnNo ratings yet

- Eye DisordersDocument68 pagesEye DisordersYasmeen zulfiqarNo ratings yet

- Poster Role of Clinical Exome SequencingDocument1 pagePoster Role of Clinical Exome SequencingLudy ArfanNo ratings yet

- Surgical Disposables List with Prices and SpecificationsDocument30 pagesSurgical Disposables List with Prices and SpecificationsshwasNo ratings yet

- ACt Vs CBT For AnxietyDocument16 pagesACt Vs CBT For Anxietymayte vaosNo ratings yet

- Advance Airway MXDocument17 pagesAdvance Airway MXMardhiyah MusaNo ratings yet

- ADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT Training Manual Final 2017Document85 pagesADVANCED LIFE SUPPORT Training Manual Final 2017Jeevan Velan94% (18)

- Non-Standardized AssessmentDocument3 pagesNon-Standardized Assessmentsyariah hairudinNo ratings yet

- Part C-35 MCQS/ 7 PP: MCQ PaediatricsDocument6 pagesPart C-35 MCQS/ 7 PP: MCQ Paediatricswindows3123100% (1)

- Warfarin CounsellingDocument2 pagesWarfarin CounsellingAnonymous 9dVZCnTXSNo ratings yet

- Guillian Barre SyndromeDocument6 pagesGuillian Barre SyndromeRhomz Zubieta RamirezNo ratings yet

- Interventions With PneumoniaDocument2 pagesInterventions With PneumoniaAnonymous qemC1CybLNo ratings yet

- Zygoma Implant Procedure GuideDocument63 pagesZygoma Implant Procedure GuideKristina Robles100% (2)

- PN Comprehensive Practice A Anad B Questions and Answers VerifiedDocument8 pagesPN Comprehensive Practice A Anad B Questions and Answers Verifiedianshirow834No ratings yet

- Biochemical tests in diabetes: Glycated haemoglobin, glucose and creatinine analysisDocument43 pagesBiochemical tests in diabetes: Glycated haemoglobin, glucose and creatinine analysisTRINEL ANGGRIATINo ratings yet

- NCP 2 Impaired Skin IntegrityDocument3 pagesNCP 2 Impaired Skin IntegrityAela Maive MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Introduction To ImmunoassaysDocument44 pagesIntroduction To Immunoassaysvidhi100% (1)

- Announcement SGU 2021Document10 pagesAnnouncement SGU 2021ceciliaNo ratings yet

- Manage Stress Through Physical ActivityDocument23 pagesManage Stress Through Physical ActivityNhedzCaidoNo ratings yet