Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Marketing

Uploaded by

Myzhel InumerableCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Marketing

Uploaded by

Myzhel InumerableCopyright:

Available Formats

17

-tennis H. Tootelian

qalph M. Gaedeke

3arl L Gordon

Massive purchasing power, geographic out-

reach and defined buying methods often

make public-aid recipients an attractive

target market for pharmacies Yet one must

question how profitable such a target might

be This study shows that pharmacy profit

levels for public-aid recipients below those

earned in marketing to fhe private-pay

patients may result in hidden benefits

Dennis H. Tootelian is Professor of Market-

ing and Director of the Center for Small

Business at California State University,

Sacramento In 1973, he received the Ph D,

in Marketing from Arizona State University

Dr Tootelian has co-authored four texts.

Marketing Principles and Applications. Mar-

keting f\Aanagemeni Cases and Readings,

Small Business Management and Small

BusinessManagemenf OperationsandPro-

'iles H IS articles have appeared in such

publications as the Journal of Marketing.

Journal of Retailing, Journal of Business

Research and California Pharmacist

Ralph M. Gaedeiw is Professor of Market-

ing at California State University, Sacra-

mento He received the Ph,D from The Uni-

versity of Washington Dr Gaedeke has

authored or co-authored six textbooks, of

which the most recent are Marketing Prin-

ciples and Applications and Small Business

Management H is articles have appeared in

such journals as the California Manage-

Review, the Journal of Consumer

and the Journal of Retailing

^ L Gordon is Associate Professor of

Decision Sciences in the School of Busi-

ness and Public Administration, Calrfomia

State University, Sacramento H e received

t'le Ph D in Business Administration from

Arizona State University in 1970 Dr Gor-

fion s research areas of emphasis include

quantitative systems, industrial engineering

and economics

MARKETING TO PUBLIC-

AID RECIPIENTS:

AN EXAMINATION OF

PHARMACY

PROFITABILITY

INTRODUCTION

Government spending for prescription Pharmaceuticals, the focal point

for this study, approaches $2 billion annuallyan amount almost evenly

split between the federal government and various state/local governmen-

tal units {The State ofSmall Business: A Report of the President. 1982). For

the approximately 50,000 pharmacies in the United States, such spending

represents a very attractive market in terms of revenue-generating poten-

tial. Despite its attractions, there are well-publicized drawbacks when

marketing to public-aid recipients. In particular, the bureaucratic problems

of "red tape" and slow reimbursement are the most commonly cited.

The purposes of the study reported here were to attempt to answer the

following two questions' (1) Is the marketing of prescription services to

public-aid recipients profitable? and, if so, (2) How do these profits compare

to private party prescription service profits? Although limited in scope, this

study analyzed the marketing of prescription Pharmaceuticals to patients

under federal or state health care programs, as prescription services

represent a significant dollar expenditure for governmental units. Further-

more, prescription services offered to patients under public-aid programs

are essentially the same as those offered private-sector patients, which

permits an analysis of the issues of profitability.

CONDUCT OF STUDY

Two evaluations were necessary to examine the extent to which

marketing prescription services to public-aid recipients is profitable and

whether or not profitability levels are comparable for similar services to the

private sector. First, to address the issue of overall profits, an average cost

of dispensing a prescription was determined This cost was defined to be

the direct costs of the prescription department (e.g., prescription supplies,

computer), plus an allocated share of the indirect costs such as utilities,

accounting services, manager's salary, etc. These costs were then divided

by the number of prescnptions dispensed. Such calculations were per-

formed using the results of published studies and industry statistics (H er-

man and Zabloski, 1978; Lilly Digest, 1982) The resulting costs were then

subtracted from the professional fee paid by federal and state health care

programs to determine the gross profit per prescription. Since states

;<oumai of HMHI I Care Marketing

- 4, No. 4 (Fan, 1984), pp. 17-21

18

pay ingredient drug costs separately, such costs were

excluded from the calculations. In California, the site of this

study, the fee paid by the Department of Health Services

under the Medi-Cal program was $3.60, plus a set rate for

the cost of the drug ingredient. A pharmacy's actual ingre-

dient cost may deviate from the reimbursed ingredient

cost approved by Medi-Cal, so attempting to separate this

highly individual cost factor would have made the survey

more cumbersomepossibly resulting in a lower response

rate. Since approved reimbursement rates are set based

on actual costs, averages were considered to be ade-

quate for the purposes of this study. Conditions in other

states are not unlike those in California relative to prescrip-

tion profitability

METHODOLOGY

Sampie

To examine the comparable profitabilities, a sample of

California chain, hospital outpatient and nonchain phar-

macies was surveyed. According to the criterion used by

the California State Board of Pharmacy, chain pharmacies

were defined to be those stores with five or more outlets.

Only hospital outpatient pharmacies were included be-

cause of the operating and pricing differences used in the

dispensing of inpatient prescriptions. These types of

pharmacies have become an increasingly competitive

factor in the retail market for prescriptions (Kubica, 1983).

From a total of 4,910 pharmacies licensed and operating in

the state, 1,109 were selected from a table of random

numbers on a probability basis of study. This sample was

divided between the three groups of pharmacies so that

the sample of 229 chain, 109 hospital outpatient, and 771

nonchain pharmacies were in proportion to the total

number of pharmacies in the state.

Data CoHection

Due to the widespread geographic distribution of the

sample population, a mail questionnaire was used for data

collection. The questionnaire was pretested on a group of

20 pharmacy owners who were selected after the sample

was drawn for the survey and were not included in the

results. The final questionnaire consisted of two parts. In

the first part, respondents were asked to price each of 40

prescriptions, 11 branded and 29 multi-source (generic)

prescription drugs, in quantities determined appropriate by

a panel of four pharmacists. The specific prescription

drugs represented the ones for which the Department of

Health Services spent the most money during the 1980-81

fiscal year, accounting for over 37% of its total Medi-Cal

drug program expenditures. The second part consisted ot

questions concerning selected store characteristics (i)

number of prescriptions dispensed per week; (2) total

prescription sales; and, (3) percent of prescriptions dis-

pensed through Medi-Cal. In addition, respondents were

asked to identify the pharmacies they most patronized so

that verifications of the prescription prices could be made

Since state law requires that prescription prices be given

to interested parties, respondent identifications would not

adversely affect response rates or the actual responses,

RESULTS

Responses to the survey on prescription prices were

received from 115 chain, 29 hospital outpatient, and 441

nonchain pharmacies, for a 53.4% response rate (see

Table 1). This was found to be adequate to provide results

at a .95 confidence level with an allowable error of + $019

Average dispensing costs are presented in Table 2.

When these dispensing costs are subtracted from the

professional fee paid by the Department of Health Ser-

vices, the result is the gross profit per prescription. As can

be seen in Table 2 (Column 4), low-volume pharmacies

do not earn as much profit on each prescription dispensed

under this public-aid program as do higher volume stores

Only when the costs can be spread out over a larger

number of prescriptions does the profitability increase

To compare levels of profitability between the private

sector and public-aid recipients, the ingredient cost of the

prescriptions was subtracted from the price responses

using industry-provided cost data. With an average retail

price of $16.13, and an average ingredient cost of $9.91,

the professional fee per prescription (i.e., price minus

ingredient cost) in the private sector was found to be $6.22,

This represented an average return on the ingredient

costs of 62.76%. Comparing the Medi-Cal professional fee

of $3.60 with the private sector fee showed that pharma-

cies received, on an average, $2.62 rrtore on a private

sector prescription than for a public-aid recipient prescrip-

tion. As shown in Table 2 (Columns 5 and 6), public-aid

prescription gross profits were found to be no greater than

34.3% of the private sector prescriptions. Thus, one private

prescription would eam the same dollar profitability derived

from between 2.9 and 4.9% of public-aid prescriptions

ImpcHiantly, the service provided for dispensing a prescrip-

tion is basically the same, except that more paperwork is

involved in the dispensing of a public-aid prescription

Also, there is ordinarily a five- to 45-day time lag before a

MtCU, Vor. 4, Ito. 4 (FaN, 19(41

19

TABLE 1

QuesUormatoe Re^xMise Rate^^^

Que^ionnalres

Mailed

Less Postal Rejection

Effectively Mailed

Total Returned

Percent Returned

Unusable Returns

Usable Returns

Percent Usable Returns

(3) This table reflects raw data

Chain

229

1

228

115

5044%

7

108

47.37%

Pfiarmacy Type

Hospital

109

10

99

29

2929%

1

28

2828%

Nonchafai

771

3

768

441

57,42%

17

424

5521%

AH

1,109

14

1,095

585

53,42%

25

560

51 14%

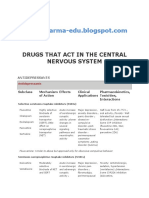

TABLE 2

Avefage costs ma Gross pronis

(1)

Store Sales Volume

Under $100,000

$100,000-$150,000

$150,000-$200,000

$200,000 - $250,000

$250,000 - $300,000

$300,000 - $350,000

$350,000 - $400,000

$400,00) - $450,000

$450,(XX) - $500,000

$500,000 - $600,000

$600,000 - $750,000

$750,000 - $1,000,000

Over $1,000,000

Average

(3) Source: Lilly Digest, 1982, pp 12-14

of Dispensing

(2)

Number

Dispensed

7236

11,040

14222

17,116

20.792

23015

26,111

27,821

31,121

33,306

38,135

50,124

56,832

27225

Prescriptions

(3)

Cost of

[Mspensing

$2 92

2 59

248

2 46

254

2,41

246

2 37

2 46

248

235

225

2.33

$2.39

(a)

(4)

Gross Profit

Prescription

$0,68

101

1 12

1 14

106

119

1 14

123

1 14

1 12

125

137

127

$121

(5)

Gross Profit

Per Private Pay

Krescnpnon

$330

363

3 74

376

3.68

3.81

376

3.65

376

374

3.87

399

3.89

$3.83

(6)

IMedi-Cal

Profitability as

% of PilvBte Psy

Profitability

206

27 8

299

30,3

28.8

312

303

31.9

303

299

32.3

343

326

316

' *^i l n9 To PHMC- AM ftedptoms: An

^fflinMonirf Phmmey ProlNAMty

20

pharmacy receives payment from the Department of

Health Services.

Further analysis of professional fees on the basis of

select variables was made to ensure that any distinct

characteristics relating to these fees were identified. As

shown in Table 3, professional fees tended to decline as

the volume of prescriptions increased above 600 per

week. Similarly, as seen in Table 3, the fees were lower in

stores with prescription sales higher than $300,000 per

year. Both of these would be expected, of course, as

normal business phenomena. More importantly, when pro-

fessional fees were compared on the basis of the percen-

tage of the pharmacy's prescriptions dispensed through

the Medi-Cal program, differences were apparent (see

Table 3). Pharmacies which have a greater proportion of

their prescription business in the Medi-Cal program,

especially those with over 40%, have higher fees (by an

average of $0.81) for private sector customers. Whether

this was the result of an attempt to defray the lower profits

of public-aid prescriptions, or reflects higher operating

costs, could not t>e determined.

CONCLUSIONS

This study sought to shed light on two of the most

critical issues in the marketing of pharmaceutical services

to public-aid recipients: (1) the profitability of such practice;

and, (2) how profits from that sector compare to profits

obtained for similar services provided to the private sector.

The results indicate that while marketing to public-aid

recipients can be profitable, the levels of profits are not

especially high for small-volume stores. To the extent that

these health care provider types concentrate much of

their limited resources to this market suggests that these

stores may be endangering their overall profitability.

Marketing to public-aid recipients, however, appears

to be beneficial to the extent that resulting revenues can

help defray the pharmacy's fixed costs. And, the increased

volume might permit purchasing on the most advantage-

ous terms possible. But, in instances where higher over-

head (e.g., an added pharmacist, an extra computer termi-

nal) might be incurred to satisfy public-aid demand, or

where the store's marketing efforts are focused on such a

sector rather than on the private sector, the incremental

profitability may be nonexistent.

The implications of the above findings are that provid-

ers should not simply be attracted by dollar sales potential

TABLE 3

Professional Fees By Select Variables

(1) PreKT^itlons DIspenwd

Number ot

PPBtcrtptioiM

Dtaperaed

Professional

Fees

Under 250

250 - 4(X)

401 - 6(D0

601 - 750

751 -1,000

Over 1,000

$6.8329

6,4523

6.7230

6.2878

5.5094

4 4099

(2) Total I

PiescrlpUon

Sales ($)

Professional

Fees

Under 100,000 $64922

100,001 -200,000 6.5445

200,001 -300,000 67193

300.001 -400,000 6.3139

400,001 -500,000 54325

Over 500,000 4.4743

(3) Percent of PreM1ptlons Dispensed Through Me<N-Cal

^Dispensed

Throui^

Med-Cal

Professional

Fees

Under 10

10-25

26-40

41 -60

61 -75

Over 75

$6.0799

5.7421

6.5595

6.9336

7.0205

65256

N=558; Z=6.46

N=542; Z=4.44

N=556; Z=4.05

JHCM, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Fan, 191^

21

ind automatically presume that marketing to public-aid

.ecipients will be highly profitable. Instead, they should

consider the lower professional fees as well as a number

of countervailing factors. To some extent, lower fees may

be offset by greater utilization of the store's existing facili-

ties and personnel. Furthermore, the added prescription

volume may improve the pharmacy's ability to purchase

on favorable terms as well as general front-end sales.

Since front-end sales account for over 45% of an average

pharmacy's total sales, some increases in nonprescription

revenues could be expected due to factors such as con-

venience. Importantly, however, these are not necessarily

assured and must be carefully analyzed.

Additionally, providers should carefully examine the

prospects of earning public-aid sector profits vis-a-vis a

more intense effort to penetrate private sector markets.

As already shown, small increases in revenues from the

private sector may well generate higher levels of profits

than do the considerably greater revenues received

under government programs. Detailed case studies of

the actual costs incurred, and the incremental revenues

generated, would be quite helpful in better assessing

this profitability issue. Such studies should, however,

cover both prescription and nonprescription costs as

well as benefits.

REFERENCES

Herman, Golman M and Edward J Zabloski (1978), ' An Assessment of Pre-

scription Dispensing Costs and Related Factors," Med/ca/Care Review 35

(August), 15

Kubica, Anthony J (1983), "Competing for Scarce Resources The Insfitutional

Pharmacists' Challenge," Current Concepts in Hospital Pharmacy Man-

agement (Spring), 6-8

Lilly Digest {\X2) Philadelphia Eli Lilly Drug Co.

The Stale ot Small Business: A Report ol ihe President (1962). US Small

Business Administration (March). 329

^"wtbtg To PubNc-AM Redptontt: An

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Katzung SummaryDocument60 pagesKatzung Summaryedwarbc1No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Treating Paranoid OrganizationDocument6 pagesTreating Paranoid Organizationredpsych103100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Electrical Stimulation Motor Points GuideDocument33 pagesElectrical Stimulation Motor Points GuideSreeraj S R100% (5)

- CPR GuidelinesDocument30 pagesCPR GuidelineswvhvetNo ratings yet

- Acrolein TestDocument6 pagesAcrolein TestJesserene Ramos75% (4)

- Neuro OSCE - Student Guide PDFDocument9 pagesNeuro OSCE - Student Guide PDFDAVE RYAN DELA CRUZ100% (1)

- Canadian Framework For Teamwork and Communications Lit ReviewDocument68 pagesCanadian Framework For Teamwork and Communications Lit ReviewanxxxanaNo ratings yet

- Doh Requirements Level 1 HospitalDocument50 pagesDoh Requirements Level 1 HospitalFerdinand M. Turbanos100% (4)

- CKD PathophysiologyDocument1 pageCKD Pathophysiologylloyd_santino67% (3)

- Wit - A Film Review, Analysis and Interview With Playwright Margaret EdsonDocument9 pagesWit - A Film Review, Analysis and Interview With Playwright Margaret EdsonamelamerNo ratings yet

- Pasion ThesisDocument55 pagesPasion ThesisMagiePasion100% (1)

- Poinsettia: Yi Pin Hong BotanyDocument1 pagePoinsettia: Yi Pin Hong BotanyMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- TOP10Document4 pagesTOP10Myzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Group 5 - Ylang YlangDocument2 pagesGroup 5 - Ylang YlangMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Semi Logarithmic Vertlog BWDocument1 pageSemi Logarithmic Vertlog BWWaseem وسیمNo ratings yet

- Universal Declaration of Human RightsDocument8 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human RightselectedwessNo ratings yet

- Saluyot: Chang Shuo Huang Ma Gen InfoDocument2 pagesSaluyot: Chang Shuo Huang Ma Gen InfoMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Saluyot: Chang Shuo Huang Ma Gen InfoDocument2 pagesSaluyot: Chang Shuo Huang Ma Gen InfoMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- AMPALAYADocument7 pagesAMPALAYAMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- CarbohydratesDocument2 pagesCarbohydratesMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Freire OppressedDocument2 pagesFreire OppressedMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- BANABADocument7 pagesBANABAMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Bio FilmsDocument14 pagesBio Filmsformalreport1996No ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument6 pagesReviewerMyzhel Inumerable100% (1)

- AcaciaDocument6 pagesAcaciaMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Statistics Lesson 2 Types Studies Data AnalysisDocument3 pagesStatistics Lesson 2 Types Studies Data AnalysisMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Vatican II Declaration on Religious FreedomDocument7 pagesVatican II Declaration on Religious FreedomMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- MouseDocument1 pageMouseMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Column ChromatographyDocument2 pagesColumn ChromatographyMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- FormularyDocument7 pagesFormularyMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- CarbohydratesDocument2 pagesCarbohydratesMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- BIOSTATDocument24 pagesBIOSTATMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Hospi Phar ReportingDocument50 pagesHospi Phar ReportingMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrate Reactions in Molisch, Benedict, Barfoed, Seliwanoff & Bial TestsDocument2 pagesCarbohydrate Reactions in Molisch, Benedict, Barfoed, Seliwanoff & Bial TestsMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Justice in The World 1Document12 pagesJustice in The World 1Myzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Evangelii GaudiumDocument20 pagesEvangelii GaudiumMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry Lab Table of ReactionsDocument4 pagesBiochemistry Lab Table of ReactionsMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Surveys Interviews Questionnaires Focus Groups Protocol TemplateDocument14 pagesSurveys Interviews Questionnaires Focus Groups Protocol TemplateMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Zel OilDocument1 pageZel OilMyzhel InumerableNo ratings yet

- Extraction of Invertase From YeastDocument1 pageExtraction of Invertase From YeastMyzhel Inumerable100% (1)

- Or JournalDocument5 pagesOr JournalEchanique, James F.No ratings yet

- GNMK IMC 20152 A EPlex BrochureDocument4 pagesGNMK IMC 20152 A EPlex BrochureBilgi KurumsalNo ratings yet

- PTSD and Medical Cannabis ProgramsDocument3 pagesPTSD and Medical Cannabis ProgramsMPP100% (1)

- Ursing Standards: Intrdocution:-Standard Is An Acknowledged Measure of Comparison For Quantitative or QualitativeDocument13 pagesUrsing Standards: Intrdocution:-Standard Is An Acknowledged Measure of Comparison For Quantitative or QualitativemalathiNo ratings yet

- GlossectomyDocument68 pagesGlossectomyRohan GroverNo ratings yet

- SedativesDocument3 pagesSedativesOana AndreiaNo ratings yet

- Resume Updated May 2017Document3 pagesResume Updated May 2017api-361492094No ratings yet

- 419 FullDocument6 pages419 Fullmarkwat21No ratings yet

- FCC Framework FINALDocument22 pagesFCC Framework FINALsriNo ratings yet

- Best Practice Statement AuditDocument2 pagesBest Practice Statement Auditns officeNo ratings yet

- EndokrinoDocument78 pagesEndokrinoJulian TaneNo ratings yet

- Prof Qaisar Khan TrialsDocument56 pagesProf Qaisar Khan TrialsAsim NajamNo ratings yet

- Elizabeth Resume 2Document3 pagesElizabeth Resume 2api-252417118No ratings yet

- CLASSIFYING GASTRITISDocument40 pagesCLASSIFYING GASTRITISmadalinamihaiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Studi Kasus AskepDocument8 pagesJurnal Studi Kasus Askepaji bayuNo ratings yet

- FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT 1 and 3 (NCP and Diet Therapy)Document5 pagesFORMATIVE ASSESSMENT 1 and 3 (NCP and Diet Therapy)Hyun Jae WonNo ratings yet

- Potassium Chloride (Ktab)Document2 pagesPotassium Chloride (Ktab)Marlisha D. BrinkleyNo ratings yet

- Question Excerpt From 96Document5 pagesQuestion Excerpt From 96Lorainne FernandezNo ratings yet

- Lung Cancer Types & TreatmentsDocument45 pagesLung Cancer Types & TreatmentsHowell Thomas Montilla AlamoNo ratings yet

- Factitious Disorder Imposed On Another IIIDocument4 pagesFactitious Disorder Imposed On Another IIIirsan_unhaluNo ratings yet