Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Drives Consumers To Spread E-WOM in Online Consumer-Opinion Platforms

Uploaded by

Liew2020Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Drives Consumers To Spread E-WOM in Online Consumer-Opinion Platforms

Uploaded by

Liew2020Copyright:

Available Formats

What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online

consumer-opinion platforms

Christy M.K. Cheung

a,

, Matthew K.O. Lee

b, 1

a

Department of Finance and Decision Sciences, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong

b

Department of Information Systems, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 10 August 2010

Received in revised form 23 November 2011

Accepted 23 January 2012

Available online xxxx

Keywords:

Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM)

communication

Public good

Online consumer reviews

Reputation

Sense of belonging

Enjoyment of helping

Electronic marketing

The advance of the Internet facilitates consumers to share and exchange consumption-related advice through

online consumer reviews. This relatively new form of word-of-mouth communication, electronic word-of-

mouth (eWOM) communication, has only recently received signicant managerial and academic attention.

Many academic studies have looked at the effectiveness of positive eWOM communication, examining the

process by which eWOM inuences consumer purchasing decisions. eWOM behavior is primarily explained

from the individual rational perspective that emphasizes a cost and benet analysis. However, we felt there

was a need for an extensive study that examines consumers' motives for eWOM. In this paper, we focus on

the factors that drive consumers to spread positive eWOM in online consumer-opinion platforms. Building

on the social psychology literature, we identied a number of key motives of consumers' eWOM intention

and developed an associated model. We empirically tested the research model with a sample of 203 members

of a consumer review community, OpenRice.com. The model explains 69% of the variance, with reputation,

sense of belonging and enjoyment of helping other consumers signicantly related to consumers' eWOM

intention. The results of this study provide important implications for research and practice.

2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

With the advent of Internet technologies, traditional word-of-

mouth communication has been extended to electronic media, such as

online discussion forums, electronic bulletin board systems, news-

groups, blogs, review sites, and social networking sites [34,44]. Every-

one can share their opinion and experience related to products with

complete strangers who are socially and geographically dispersed

[19]. This new form of word of mouth, known as electronic word of

mouth (eWOM), has become an important factor in shaping consumer

purchase behavior. Hennig-Thurau et al. [27] argued that information

provided on consumer opinion sites is more inuential among

consumers nowadays. Industrial statistics have also provided evidence

in supporting the signicant impact of eWOM communication. For

instance, eMarketer revealed that 61% of consumers consulted online

reviews, blogs and other kinds of online customer feedback before

purchasing a new product or service [22]. In addition, 80% of those

who plan to make a purchase online will seek out online consumer

reviews before making their purchase decision [29]. Some consumers

even reported that they are willing to pay at least 20% more for services

receiving an Excellent, or 5-star, rating than for the same service

receiving a Good, or 4-star rating [15].

Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) communication has only

recently received signicant managerial and academic attention. Most

academic studies have looked at the effectiveness of eWOM communi-

cation, examining the process by which eWOM inuences consumer

purchasing decisions. To date, the issue of consumers' eWOM intention

has received limited attention in the IS literature. We still do not

fully understand why consumers spread positive eWOM in online

consumer-opinion platforms. Among the few existing publications,

eWOM behavior is primarily explained from individual rational

perspective with the emphasis on cost and benet. Consumer participa-

tion in online consumer-opinion platforms depends a lot on interac-

tions with other consumers. We believe that it is necessary to further

extend existing work by adopting a diverse theoretical perspective to

explain this new social phenomenon focusing on antecedents to

eWOM intentions. In the second section of this paper, we address the

theoretical background. Then, we present our research model and

hypotheses; and describe a survey study of users in an online

consumer-opinion platform to empirically test the research model.

Next, we discuss the ndings of our empirical study. And nally, we

conclude by describing the implications for both research and practice,

the limitations of the study, and future research directions.

Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Corresponding author. Tel.: +852 34112102; fax: +852 34115585.

E-mail addresses: ccheung@hkbu.edu.hk (C.M.K. Cheung), ismatlee@cityu.edu.hk

(M.K.O. Lee).

1

Tel: +852 27887348; fax: +852 27888694.

DECSUP-12005; No of Pages 8

0167-9236/$ see front matter 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Decision Support Systems

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er . com/ l ocat e/ dss

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

2. Theoretical background

Prior literature provides a rich foundation of theory on which to

build a research model that explains why consumers are willing to

spread positive eWOM in online consumer-opinion platforms. In this

section, we rst dene electronic word-of-mouth communication and

compare the concept with traditional word-of-mouth communication.

We then describe the theoretical foundation of our research model.

2.1. Denition of eWOM communication

With the advent of the Internet, there has been a paradigm shift in

word-of-mouth communication. Traditional word-of-mouth (WOM),

which was originally dened as an oral form of interpersonal non-

commercial communication among acquaintances [5], has evolved

into a new form of communication, namely electronic word-of-mouth

(eWOM) communication. eWOM communication can take place in

various settings. Consumers can post their opinions, comments and

reviews of products on weblogs (e.g. xanga.com), discussion forums

(e.g. zapak.com), review websites (e.g. Epinions.com), retail websites

(e.g., Amazon.com), e-bulletin board systems, newsgroup and social

networking sites (e.g. facebook.com).

eWOM differs from traditional WOM in many ways. First, unlike

traditional WOM, eWOM communications possess unprecedented

scalability and speed of diffusion. eWOM communications involve

multi-way exchanges of information in asynchronous mode [27,28].

The use of various electronic technologies such as online discussion

forums, electronic bulletin boards, newsgroups, blogs, review sites

and social networking sites facilitate information exchange among

communicators [33]. Second, eWOM communications are more per-

sistent and accessible than traditional WOM. Most of the text-based

information presented on the Internet is archived and thus, in many

cases, at least in theory, is available for an indenite period of time

[28,37]. Third, eWOM communications are more measurable than

traditional WOM. The presentation format, quantity and persistence

of eWOM communications have made them more observable. Lastly,

the electronic nature of eWOM in most applications may dampen the

receiver's ability to judge the sender and his or her message on factors

such as credibility. People can only judge the credibility of the com-

municator based on the associated cues through online reputation

systems (online ratings, website credibility, etc.).

2.2. Prior research on eWOM communication

The topic of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) communication

is generating increased interest in business disciplines such as mar-

keting, consumer behavior, economics, and information systems. Re-

searchers have adopted various research approaches to examine this

important phenomenon. Most of these different research approaches

explore the impact of eWOM communication. However, research on

why consumers engage in eWOM in online consumer-opinion plat-

forms remains relatively limited. A prominent study of eWOM

communication motives is by Henning-Thurau et al. [27]. They built

on Balasubramanian and Mahajan [6], identifying ve main motiva-

tional categories of positive eWOM communication: focus-related

utility (concern for other consumers, helping the company, social

benets, and exerting power), consumption utility (post-purchase

advice-seeking), approval utility (self-enhancement and economic re-

wards), moderator-related utility (convenience and problem-solving

support), and homeostase utility (expressing positive emotions and

venting negative feelings). Sun et al. [39] also proposed an integrated

model to explore the antecedents and consequences of eWOM in the

context of music-related communication. They found that innovative-

ness, internet usage, and internet social connection are signicant

factors in eWOM behavior. Tong et al. [41] explored costs (cognitive

cost and executional cost) and benets (enjoyment in helping other

consumers and enjoyment in inuencing the company, self-

enhancement, andeconomic reward) of consumer's informationcontri-

bution to online feedback systems. These studies provide a reasonable

start to exploring further the motives behind eWOM communication

in a way that does not necessarily approach eWOMbehavior as individ-

ual rational phenomenon.

2.3. The public good

Inthe literature, informationsharing is viewedas a public-good phe-

nomenon. A public good is characterized as a shared resource from

which every member of a group may benet, regardless of whether or

not they personally contribute to its provision, and whose availability

does not diminish with use (p. 693) [11]. The fundamental problem

of a public good is that any individual may consume a public good with-

out contributing to a group. This results in a social dilemma situation,

which occurs when an individual attempts to maximize self-interest

over social-interest and makes a rational decision. In the online envi-

ronment, anyone can access and consume knowledge without making

a direct contribution back to it. It is very likely that individuals will

free-ride [9,30]. Wasko and Tiegland [43] however urged that though

public goods are subjected to social dilemmas, they are nonetheless

created and maintained through collective action. In other words,

public goods are still shared and contributed to voluntarily through

cooperation of individuals. Based on the social psychology literature,

we identied four perspectives that explain why consumers spread

eWOM in online consumer-opinion platforms: egoism, collectivism,

altruism, and principlism.

Egoism refers to serving the public good to benet oneself. Re-

searchers in psychology, sociology, economics, and political sciences

assume that all human actions are ultimately directed toward self-

interest. Rewards and avoidance are the most obvious self-benets

that drive individuals to act for the public good. Collectivism refers to

serving the public good to benet a group. The act for the public good

is for the group's benet, as the self shifts frompersonal self to collective

self. This is the most widely accepted social psychology theory of group

behavior. Altruism refers to serving the public good to benet one or

more others. The motive for the public good can be linked to empathic

emotion. Empathy (feelings of sympathy, compassion, tenderness,

and the like) is a source of altruism. Some researchers have shown

that feeling empathy for a person in need leads to increased helping

of that person [20]. Principlism refers to serving the public good to

uphold a principle. The motivation is to uphold, typically, some moral

principle, such as justice or the utilitarian principle of the greatest

good for the greatest number. Gorsuch and Orberg [24] found that in

moral situations, people reported their intentions to act out of their

sense of moral responsibility.

2.4. Knowledge self-efcacy

Prior studies [33] have demonstrated that knowledge self-efcacy is

an important antecedent of knowledge sharing in the online environ-

ment. Individuals tend to provide useful advice on computer networks

if they possess a high level of expertise [17]. Conversely, when they

lack information or knowledge which is useful to others, they tend to

make less contribution in knowledge sharing since, for example they

believe that they cannot make a positive impact for the organization

[30]. Insufcient knowledge self-efcacy also hinders individuals to

share in web-based discussion boards [33].

This line of study suggests that people form beliefs about what

they can do, predict likely outcomes of prospective actions, and set

goals for themselves in order to achieve desired outcomes. In other

words, the motivations of performing a behavior do not stem from

the goals themselves, but from the self-evaluation that is made condi-

tional on their fulllment. Bandura [7] denes perceived self-efcacy

as people's beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated

2 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

levels of performance that exercise inuence over events that affect

their lives (p. 71). Self-efcacy is created through mastery experi-

ence. Success builds a strong belief in one's self-efcacy and moti-

vates an individual to continue the behaviors.

3. Research model and hypotheses

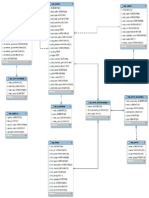

Based on the literature reviewed above, we develop a model of an-

tecedents to eWOMintentions in online consumer-opinion platforms,

depicted in Fig. 1. The antecedent variables are from four different

theoretical perspectives as well as knowledge self-efcacy. Our

focus is on intentions to behave as, however indeed a relationship be-

tween intention and behavior is well established [1]. In this section,

the key components of the research model and their interrelation-

ships are addressed.

3.1. Egoistic motivation

A motive is considered egoistic if the ultimate goal is to increase the

actor's own welfare [8]. Individuals are deemed as egoistic when they

aim at tangible or intangible returns after sharing information with

others. Social exchange theory has been adopted to explain the action

for the public good interms of egoismin recent years [9,30]. Being ratio-

nal, human beings try to look for returns (e.g. pay, prizes, reputation,

and recognition) by maximizing their benets and minimizing their

cost during information exchange process with others [32].

This perspective has been widely adopted in many eWOM commu-

nication publications [27,41]. For example, reputation is often cited as

animportant determinant of informationsharing behavior [16,17]. Peo-

ple share and contribute their knowledge because they want to gain an

informal recognitionand establishthemselves as experts [43]. Similarly,

we believe that if a consumer wants to gain a reputation in an online

consumer-opinion platform, he/she has a higher tendency to spread

eWOM. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1. The perception of the opportunity to enhance one's own reputa-

tions is positively related to one's eWOM intention.

Another egoistic motivator of the act for the public good is reci-

procity, which is also conceived as a benet for individuals to engage

in social exchange. When information providers do not know each

other, the kind of reciprocity that is relevant is called generalized

exchange [21], and the person who offers help to others is expecting

returns in the future [32]. Prior research found that people who share

knowledge in online communities value reciprocity [42], and it is this

belief that drives them to participate and share. Thus, this leads to the

following hypothesis:

H2. The perception of the opportunity for reciprocity is positively re-

lated to one's eWOM intention.

3.2. Collective motivation

Collectivism is dened as the motivation with the ultimate goal of

increasing the welfare of a group or collective [8]. In other words, in-

dividuals with a collective motive contribute their knowledge for the

benet of the whole group rather than personal return. In terms of ac-

tion for the public good, collectivism can be linked to social identity

theory, in which individuals gain social identity from the groups

they belong to [40]. When individuals identify themselves as mem-

bers of a social aggregate, they are more likely to dene themselves

in terms of their membership in that group [18]. Members have the

feeling that others' needs will be satised by the resources received

through their contributions to the group [35].

Sense of belonging refers to a sense of emotional involvement

with the group. When people identify themselves as part of the com-

munity and align their goals with those of the community, they will

treat other members as their kin and they will be willing to do some-

thing benecial to/for others that are not necessarily benecial [26].

Lakhani and Von Hipper [32] also argued that committed electronic

network members take part in knowledge sharing since they think

such behavior is best for the community. Hence, people with this var-

iant of intrinsic motivation will be motivated to participate in sharing

activities and help their kinship partners.

Fig. 1. Research model.

3 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

H3. The opportunity for the sense of belonging is positively related to

one's eWOM intention.

3.3. Altruistic motivation

Altruism is motivation with the ultimate goal of increasing the

welfare of one or more individuals other than oneself [8]. Individuals

acting on altruistic goals are willing to volunteer themselves to con-

tribute their knowledge to online consumer reviews without expect-

ing direct rewards in return. For example, consumers may share

purchasing experience just because others have a need for it [31].

When studied in terms of empathic emotion, individuals may have

empathy toward a person in need and this increases helping of that

person [8].

Enjoyment of helping has been acknowledged by researchers as an

altruistic factor to explain individuals' willingness to share knowledge

in electronic networks of practice or online social spaces [27,30,41].

Though there is no apparent compensation, people in virtual communi-

ties still obtain intrinsic enjoyment and satisfaction by helping others

through sharing their knowledge [4,31,42]. Hence,

H4. The opportunity to realize personal enjoyment is positively related

to one's eWOM intention.

3.4. Principlistic motivation

Principlismrefers to the motivation towards the ultimate goal of up-

holding some moral principle, such as justice or the utilitarian principle

of the greatest goodfor the greatest number [8]. The predictive power of

principlistic motivation on behavioral intention has been supported by

various empirical studies [24]. Action for the public good in terms of

principlismcan be explained by normative commitment, in whichcom-

mitment is a sense of obligationto the organization[3,36]. Witha strong

sense of commitment to the community, individuals in virtual commu-

nities are more likely to feel obliged to help others by contributing

knowledge [18]. They are willing to contribute their knowledge to the

well being of the organization [36].

Moral obligation is derived fromprinciplism. Commitment to online

communities conveys a sense of duty or obligation to help others on the

basis of shared membership [41]. In the context of an organization,

people view their knowledge as a public good and they are motivated

to have knowledge exchange with others because of moral obligation

and community interest [3]. In online communities, individuals with a

strong sense of commitment to the community are more likely to feel

obliged to help others by contributing knowledge [43]. Therefore, we

believe that when a consumer has a strong sense of moral obligation,

there will be a higher chance for them to spread eWOM in online

consumer-opinion platforms.

H5. The opportunity to feel a moral obligation is positively related to

one's eWOM intention.

3.5. Knowledge self-efcacy

In social cognitive theory, self-efcacy is a personal judgment of

one's capability to execute actions required for designated types of

performances. It has a great impact on people's intentions and behavior

[7]. Derived from this line of study, knowledge self-efcacy can be

served as a self-motivator for knowledge contribution in online

platforms. Previous studies have already illustrated the importance of

knowledge self-efcacy on people's intention to share knowledge

[30]. We also believe that a higher knowledge self-efcacy about a

purchasing experience, leads to a higher tendency to spread eWOM in

online consumer-opinion platforms.

H6. The degree of perceived knowledge self-efcacy is positively re-

lated to one's eWOM intention.

4. Research method

The research model was examined using a sample of online

consumer-opinion platformusers fromOpenRice.com. OpenRice.com,

one of the most successful online communities in Hong Kong, shares

information about 15,000 restaurants in Hong Kong and Macau. It is a

good search tool with all restaurant information categorized in terms

of the style of food, location of the restaurant, price ranges, and the

like.

4.1. Data collection

In this study, the sample frame was individuals who have used

OpenRice.com. A convenience sample was used by inviting volunteers

to participate in this study. We posted an invitation message with the

URL to the online questionnaire on a number of Facebook groups re-

lated to dining experiences in Hong Kong. To increase the response

rate, entry in a lottery for supermarket vouchers was offered as an in-

centive for participation.

4.2. Sample prole

The respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire based

on their experience with OpenRice.com. A total of 203 usable ques-

tionnaires were collected in this study. Among the 203 respondents,

57% was female and 43% was male. A majority of our respondents

(67%) were aged between 21 and 25. 78% of our respondents had

an education level of university or above.

4.3. Measures

The constructs of interest in this study included consumers' eWOM

intention, reputation, reciprocity, sense of belonging, enjoyment of

helping, moral obligation, and knowledge self-efcacy. We used estab-

lished measures from previous literature (See Appendix A). All con-

structs were measured using multi-item perceptual scales and were

carried out by a seven-point Likert scale, ranging fromstrongly disagree

(1) to strongly disagree (7).

5. Data analysis and results

The Partial Least Squares (PLS) method was used to perform the

statistical analysis in this study. PLS technique provides a better ex-

planation for complex relationships [23] and is widely adopted by IS

researchers [13]. Moreover, it is suitable when the focus of the re-

search is on theory development. Following the two-step analytical

approach [25], we rst conducted the psychometric assessment of

our measurement scales, and we then evaluated the structural

model. Using this approach, we have a higher condence that the

conclusion on structural relationship is drawn from a set of measure-

ment instruments with desirable psychometric properties.

5.1. Measurement model

The convergent validity and discriminant validity of the constructs

in our model were examined. Convergent validity was tested using

three criteria of all constructs: (1) the composite reliability (CR)

should be at least 0.70 [13], (2) the average variance extracted

(AVE) should be at least 0.50 [23], and (3) all item loadings should

be greater than 0.707 [13]. Results of our analysis are shown in

Table 1. All three conditions of convergent validity were satised in

our data sample by having the CRs ranging from 0.89 to 0.96, and

4 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

the AVEs from0.67 to 0.93. The itemloadings were all higher than the

0.707 benchmark.

Discriminant validity is indicated by low correlations between the

measure of interest and the measure of other constructs [23]. This va-

lidity can be assessed by having the square root of the average vari-

ance extracted (AVE) of each construct higher than the correlations

between it and all other constructs. As shown in Table 2, the square

root of the AVE of each construct is located on the diagonal of the

table and is in bold. A reasonable degree of discriminant validity ob-

tains since each of them is greater than the correlations between it

and all other constructs. We followed Segars and Grover's [38] guide-

line and further tested the correlations between enjoyment of help-

ing, moral obligation, and sense of belonging. First, a model

imposing a correlation of 1 between the two specic constructs is

run. Then, another model with a freely estimated correlation between

the two constructs is run. Discriminant validity is demonstrated if

there is a signicant difference of the Chi-square statistics (i.e., Chi-

square difference is greater than 3.84) between the constrained (the

correlation between constructs is set) and unconstrained models

(the correlation between constructs is free). In the current study, ro-

bust evidence of convergent validity and discriminant validity was

found with these data.

5.2. Structural model

The structural model analysis was assessed based on the test of

the hypothesized effects in our research model. Fig. 2 shows the

results of the hypothesized structural model test, including the vari-

ance explained (R

2

value) of the dependent variable, estimated path

coefcients with signicant paths indicated by asterisks, and associated

t-values of the paths. Bootstrap resampling procedure was used to per-

form the signicant testing for each path.

An examination of the R

2

value demonstrates that the model

explains a substantial amount of the variance in the outcome variable.

In our model, it explains 69% of the variance in consumers' eWOM

intention. The signicant antecedents are reputation, sense of belonging

and enjoyment of helping, with path coefcients at 0.11, 0.41 and 0.33

respectively. This provides support for H1, H3 and H4.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Given the limited research in the area of consumers' intention to

spread eWOM in online consumer-opinion platforms, this study seeks

to consider the factors that shape eWOM behavior. This section dis-

cusses the results of hypothesis testing of the researchmodel, addresses

the limitations of the study, and highlights the contributions to research

and practice.

6.1. General discussion

The research model gains much of its theoretical foundation from

the social psychology literature. The analysis shows that consumers'

eWOM intention is signicantly related to three antecedents, reputa-

tion (marginal signicance), sense of belonging, and enjoyment of

helping.

Sense of belonging had relatively the most impact on consumers'

eWOM intention. The result is consistent with previous eWOM

marketing literature, where affective commitment (sense of belong-

ing) is an essential ingredient that fosters loyalty and citizenship in

a group [18]. In our case, consumers who have a stronger sense of

belonging to OpenRice.com have greater citizenship intentions

(e.g., sharing dining experiences with other consumers). This also

illustrated the importance of including social factors in the current

investigation. Our study also showed that enjoyment of helping others

is crucial in affecting consumers' eWOM intention. Intentions to write

about dining experiences in OpenRice.com demonstrate enjoyment of

helping others. Consumers can benet other community members

through helping them with their purchasing decisions. Specically,

this act can save others fromhaving negative experiences when visiting

substandard restaurants. Reputation is a marginally signicant factor

affecting consumers' eWOM intention. Consumers spreading eWOM

in online consumer-opinion platforms related to a desire to alter repu-

tation. These consumer-opinion platforms have enormous potential for

scale and reach. Some consumers are willing to contribute dining expe-

riences because they may want to be viewed as an expert by a large

group of consumers.

Reciprocity, moral obligation and knowledge self-efcacy did not

demonstrate a signicant relationship with consumers' eWOM inten-

tion. Unlike internal knowledge sharing systems, members on OpenRi-

ce.compost their reviews based on their experiences in visiting specic

restaurants. The opinion in these online reviews helps other diners to

judge whether the restaurants are worth visiting. The experience they

share does not necessary lead to a future request for knowledge being

met. The results are consistent with some research which shows reci-

procity does not inuence the intention to use a knowledge mechanism

[14]. In addition, as OpenRice.com is an informal consumer-based

community, members may have sense of belonging, but the commit-

ment to OpenRice.com does not necessarily convey a sense of duty or

obligation to help others on the basis of shared membership. Providing

consumer reviews is on voluntary basis, which means users have the

right to decide if they would like to leave their comments. Principlism

might have more impact when the obligation is stipulated in explicit

terms. For instance, the moderator of the platform should include the

terms of use (e.g., with an emphasis on the obligation to share and

help other users) during user registration. Finally, whether they are

Table 1

Psychometric properties of measures.

Construct Item Loading t-value Mean St. dev

Knowledge self-efcacy

CR=0.91; AVE=0.84

SE1 0.88 14.64 4.91 1.38

SE2 0.95 56.50 4.27 1.46

Enjoyment of helping

CR=0.96, AVE=0.89

EH1 0.93 78.81 4.15 1.48

EH2 0.95 83.73 4.28 1.45

EH3 0.95 111.36 4.31 1.40

Consumers' eWOM intentions

CR=0.92, AVE=0.79

INT1 0.90 57.23 3.94 1.55

INT2 0.91 61.07 3.70 1.57

INT3 0.85 32.61 4.03 1.51

Moral obligation

CR=0.92, AVE=0.79

MO1 0.93 96.38 3.98 1.46

MO2 0.86 28.77 4.22 1.54

MO3 0.88 43.16 3.59 1.48

Reputation

CR=0.96, AVE=0.93

RP1 0.96 179.09 3.58 1.51

PR2 0.97 190.60 3.50 1.54

Sense of belonging

CR=0.94, AVE=0.77

SB1 0.87 44.04 3.81 1.59

SB2 0.81 23.14 4.07 1.49

SB3 0.91 72.30 3.68 1.52

SB4 0.90 62.31 3.63 1.48

SB5 0.88 63.59 3.52 1.60

Reciprocity

CR=0.89; AVE=0.67

RC1 0.77 5.41 4.61 1.28

RC2 0.81 5.04 5.00 1.38

RC3 0.88 4.43 4.98 1.32

RC4 0.80 3.53 4.86 1.36

Notes: CRComposite Reliability, AVEAverage Variance Extracted.

Table 2

Correlation matrix and psychometric properties of key constructs.

EH INT MO RC RP SE SB

Enjoyment of Helping (EH) 0.94

Consumers' eWOM Intentions (INT) 0.73 0.89

Moral Obligation (MO) 0.71 0.68 0.89

Reciprocity (RC) 0.20 0.13 0.09 0.82

Reputation (RP) 0.52 0.63 0.66 0.09 0.96

Knowledge Self-Efcacy (SE) 0.17 0.22 0.11 0.59 0.12 0.92

Sense of Belonging (SB) 0.72 0.79 0.75 0.16 0.73 0.22 0.87

Notes: Italicized diagonal elements are the square root of AVE for each construct. Off-

diagonal elements are the correlations between constructs.

5 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

frequent patrons or rst-time diners, all are welcome to provide re-

views about restaurants they have visited. Reviewers in OpenRice.com

may bear no thorough understanding about the restaurants and may

simply express their opinion based on the service quality they received.

Thus, knowledge self-efcacy does not have a signicant impact on

consumers' eWOM intentions in online consumer-opinion platforms.

6.2. Limitations and future research directions

In interpreting the results of this study, one must pay attention to a

number of limitations. Our review of prior literature indicates that

research on consumer engagement in eWOM communication remains

relatively newandhas only receivedlimitedattentioninthe scholarly lit-

erature. To enhance the understanding of this phenomenon and

contribute towards the developing of the existing literature in this area,

we propose a theoretical model that explains consumers' eWOM inten-

tion. In the current investigation, we included only the key motives

from each of the four perspectives of the social psychology literature.

Though the explanatory power of our research model is high, we believe

that future researchstudies shouldinclude some other relatedconstructs

(e.g., rewards, subjective norm, costs, etc.) to account for the remaining

unexplained variance in consumers' eWOM intention. As prior studies

have found that positive eWOM is more likely to occur than negative

eWOM, in the current study, we only focused on consumers' intention

to spread positive eWOM. In line with recent research showing the neg-

ativity bias in online consumer behavior [12], future studies should con-

tinue to explore the motives that drive users to spread negative eWOM.

The sample size is relatively small and it is a convenience sample

comprised mostly of students. This suggests that future research should

include a more diverse sample of potential users in different age catego-

ries, professions, and usage experience with the consumer-opinion

platforms. A larger sample size can also bring more statistical power

for analysis. Finally, since only a single questionnaire was used to mea-

sure all the constructs in our study, common method bias may exist in

the measurement. Further studies could test our model by using differ-

ent research methods to overcome this weakness.

6.3. Implications

Though existing academic research has signicantly advanced our

understanding of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), much of it is

focused on how online consumer reviews affect sales of products and

services. Limited attention has been devoted to the antecedents of

eWOM. In view of this, we attempt to investigate consumers' eWOM

intention in the current study. We believe that this study contributes

to the conceptual and empirical understanding of eWOM intentions in

online consumer-opinion platforms. Implications of this study are note-

worthy for both researchers and practitioners.

This study contributes to existing eWOM research in several ways.

First, a lot of existing eWOM studies focus primarily on the impact of

eWOM on consumer purchasing decision. There is a lack of under-

standing of how and why consumers are willing to spend their own

time to share their purchasing experiences with other people in the

online environment. This study enriches the existing literature by

proposing a theoretical model that explains consumers' eWOM inten-

tion. Second, the research model gains its theoretical foundation from

the social psychology literature and social cognitive theory. Particu-

larly, we provided empirical support that social factor such as sense

of belonging, also exhibits signicant impact on eWOM intentions in

online consumer-opinion platforms. The empirical investigation

demonstrates the relative importance of various antecedent factors

for consumers' eWOM intention.

The nding of this research is also useful for online consumer-

opinion platforms' moderators in understanding their members'

(Note: *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01)

Fig. 2. Result of the research model.

6 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

behaviors. The results of this study show that sense of belonging to the

community, reputation, and enjoyment of helping others are the most

critical factors that encourage consumers to share their experiences

with others in the context of online consumer-opinion platforms. Here

are some guidelines for online consumer-opinionplatforms' moderators:

Sense of belonging: To enhance consumers' sense of belonging to

an online consumer-opinion platform, platform moderators

should allow consumers to create their own personal prole. Sim-

ilar to social networking platforms such as Facebook, adding other

users as friends and directly communicating with them may cre-

ate a stronger sense of belonging to the group.

Reputation: To encourage more consumers to share their opinions,

online consumer-opinion platforms should apply reputation-

tracking mechanisms to recognize contributors. Apart from the

number of contributions, publicly visible cues such as length of

membership and membership status should be incorporated into

the platform design.

Enjoyment of helping: Online opinion-platforms should provide a

mechanism where members who have provided useful suggestions

to other members are identied and informed that they have helped

others. Connecting contributors and readers via person-to-person

messaging/chat function can enable readers to showtheir apprecia-

tion for the reviews received.

In conclusion, electronic word-of-mouth communication in online

consumer opinion platform represents new and important e-

marketing phenomenon, we hope that it triggers additional theorizing

and empirical investigation aimed at better understanding of eWOM

communication in social media.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the generous support of

the Hong Kong Baptist University for the project (HKBU 240609)

without which the timely production of the current report/publica-

tion would not have been feasible. In addition, the work described

in this paper was partially supported by a grant from City University

of Hong Kong (Project No. 7002640).

Appendix A. Measures

References

[1] I. Ajzen, From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior, in: J. Kuhl, J.

Beckmann (Eds.), Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior, Springer-Verlag,

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, 1985.

[2] R. Algesheimer, U.M. Dholakia, A. Hermann, The social inuence of brand commu-

nity: evidence from European car clubs, Journal of Marketing 69 (3) (2005)

1934.

[3] N.J. Allen, J.P. Meyer, Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the

organization: an examination of construct validity, Journal of Vocational Behavior

49 (3) (1996) 252276.

[4] R. Arakji, R. Benbunan-Fich, M. Koufaris, Exploring contributions of public resources

in social bookmarking systems, Decision Support Systems 47 (3) (2009) 245253.

[5] J. Arndt, Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product,

Journal of Marketing Research (4) (1967) 291295.

[6] S. Balasubramanian, V. Mahajan, The economic leverage of the virtual communi-

ty, International Journal of Marketing Research 5 (3) (2001) 103138.

[7] A. Bandura, Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Theory,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood, NJ, 1986.

[8] C.D. Batson, Why act for the public goods? Four answers, Personality and Social

Psychology 20 (5) (1994) 603610.

[9] G.W. Bock, R.W. Zmud, J.N. Lee, Behavioral intention formation in knowledge

sharing: examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, socialpsychological forces,

and organizational climate, MIS Quarterly 29 (1) (2005) 87112.

[10] M. Bosnjak, T.L. Tuten, W.W. Wittmann, Unit non response in web access panel

surveys: an extended planned-behavior approach, Psychology and Marketing

22 (16) (2005) 489505.

[11] A. Cabrera, F.E. Cabrera, Knowledge-sharing dilemmas, Organizational Studies 23

(5) (2002) 687710.

[12] C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, User satisfaction with an internet-based portal: an

asymmetric and nonlinear approach, Journal of the American Society for Informa-

tion Science and Technology 60 (1) (2009) 111122.

[13] W.W. Chin, in: G. Marcoulides (Ed.), The Partial Least Squares Approach to Struc-

tural Equation Modeling, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, 1998,

pp. 189217.

[14] C.M. Chiu, M.H. Hsu, E.T.G. Wang, Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual

communities: an integration of social capital and social cognitive theories, Deci-

sion Support Systems 42 (3) (2006) 18721888.

[15] ComScore Inc., Online consumer-generated reviews have signicant impact on

ofine purchase, http://www.comscore.com/Press_Events/Press_Releases/2007/

11/Online_Consumer_Reviews_Impact_Ofine_Purchasing_Behavior2007.

[16] D. Constant, S. Kiesler, L. Sproull, What's mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes

about information sharing, Information Systems Research 5 (4) (1994) 400421.

[17] D. Constant, L. Sproull, S. Kiester, The kindness of strangers: the usefulness of elec-

tronic weak ties for technical advice, Organization Science 7 (2) (1996) 119135.

[18] U.M. Dholakia, R.P. Bagozzi, L.K. Pearo, A social inuence model of consumer par-

ticipation in network- and small-group-based virtual communities, International

Journal of Research in Marketing 21 (3) (2004) 241263.

Reputation (modied from [42])

RP1 I feel that my participation in OpenRice.com improves my status in the

profession. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

RP2 I participate in OpenRice.com to improve my reputation in the profession.

(Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

Reciprocity (RC1-3: modied from [30]; RC4: modied from [43])

RC1 When I share my knowledge through OpenRice.com, I believe that I will get

an answer for giving an answer. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

RC2 When I share my knowledge through OpenRice.com, I expect somebody to

respond when I'm in need (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

RC3 When I contribute knowledge to OpenRice.com, I expect to get back

knowledge when I need it (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

RC4 I know that other members in OpenRice.com will help me, so it's only fair to

help other member. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

Sense of belonging (modied from [2])

SB1 I am very attached to OpenRice.com community. (Extremely disagree/

Extremely agree)

SB2 Other OpenRice.com members and I share the same objectives. (Extremely

disagree/Extremely agree)

SB3 The friendships I have with other OpenRice.com members mean a lot to me.

(Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

SB4 If OpenRice.com members planned something, I would think of as

something we would do rather than something they would do.

(Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

SB5 I see myself as a part of OpenRice.com. (Extremely disagree/Extremely

agree)

Enjoyment of helping (modied from [43])

EH1 I like helping other members in OpenRice.com. (Extremely disagree/

Extremely agree)

EH2 It feels good to help others other members in OpenRice.com. (Extremely

disagree/Extremely agree)

EH3 I enjoy helping other member in OpenRice.com. (Extremely disagree/

Extremely agree)

Moral obligation (modied from [10])

MO1 My conscience calls me to contribute and share in OpenRice.com.

(Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

MO2 My decision to share or not in OpenRice.com is fully in line with my moral

conviction. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

MO3 I feel morally obliged to share in OpenRice.com. (Extremely disagree/

Extremely agree)

Consumers' eWOM intention (modied from [9])

INT1 I intend to share my dining experiences with other members in

OpenRice.com more frequently in the future. (Extremely disagree/

Extremely agree)

INT2 I will always provide my dining experiences at the request of other

members in OpenRice.com. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

INT3 I will try to share my dining experiences with other members in

OpenRice.com in a more effective way (Extremely disagree/Extremely

agree)

Knowledge self-efcacy (modied from [30])

SE1 I have condence in my ability to provide knowledge/Information that

others in Open Rice.com consider valuable. (Extremely disagree/Extremely

agree)

SE2 I have the expertise needed to provide valuable knowledge/Information for

Open Rice.com. (Extremely disagree/Extremely agree)

7 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

[19] W. Duan, B. Gu, A.B. Whinston, Do online reviews matter? An empirical inves-

tigation of panel data, Decision Support Systems 45 (4) (2008) 10071016.

[20] N. Eisenberg, P.A. Miller, The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors,

Psychological Bulletin 101 (1) (1987) 91119.

[21] P. Ekeh, Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions, Harvard University Press,

Cambridge, MA, 1974.

[22] eMarketer.com., Online review sway shoppers, http://www.emarketer.com/

Article.aspx?R=10064042008Last accessed.

[23] C. Fornell, D.F. Larcker, Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable

variables and measurement error, Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1981) 3950.

[24] R.L. Gorsuch, J. Orberg, Moral obligation and attitudes: their relation to behavioural

intentions, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (5) (1983) 10251028.

[25] J.F. Hair, W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tatham, Multivariate Data Anal-

ysis, 6th Eds Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2006.

[26] A. Hars, S. Ou, Working for Free? Motivations of participating in open source pro-

jects, International Journal of Electronic Commerce 6 (3) (2002) 2539.

[27] T. Henning-Thurau, K.P. Gwinner, G. Walsh, D.D. Gremler, Electronic word of

mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: what motivates consumers to articulate

themselves on the Internet, Journal of Interactive Marketing 18 (1) (2004) 3852.

[28] K. Hung, S. Li, The inuence of eWOM on virtual consumer communities: social

capital, consumer learning, and behavioral outcomes, Journal of Advertising

Research 47 (4) (2007) 485.

[29] Infogroup Inc., Online consumer reviews signicantly impact consumer purchasing

decisions, http://www.opinionresearch.com/leSave/Online_Feedback_PR_Final_

6202008.pdf2009.

[30] A. Kankanhalli, B.C.Y. Tan, K.K. Wei, Contribution knowledge to electronic knowl-

edge repositories: an empirical investigation, MIS Quarterly 29 (1) (2005)

113143.

[31] P. Kollock, The economies of online cooperation: gifts, and public goods in cyber-

space, in: M.A. Smith, P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in Cyberspace, Routledge,

New York, 1999, pp. 220239.

[32] K.R. Lakhani, E. Von Hipper, How open source software works: free user-to-user

assistance, Research Policy 32 (6) (2003) 923943.

[33] M.K.O. Lee, C.M.K. Cheung, K.H. Lim, C.L. Sia, Understanding customer knowledge

sharing in web-based discussion boards: an exploratory study, Internet Research

16 (3) (2006) 289303.

[34] F. Li, T.C. Du, An ontology-based opinion leader identication framework for

word-of-mouth marketing in online social blogs, Decision Support Systems 51

(1) (2011) 190197.

[35] D.W. McMillan, D.M. Chavis, Sense of community: a denition and theory, Journal

of Community Psychology 14 (1) (1986) 623.

[36] R.T. Mowday, R.M. Steers, L. Porter, The measurement of organizational commit-

ment, Journal of Vocational Behavior 14 (1979) 224247.

[37] C. Park, T. Lee, Information direction, website reputation and eWOM effect: a

moderating role of product type, Journal of Business Research 62 (1) (2009)

6167.

[38] A.H. Segars, V. Grover, Re-examining perceived ease of use and usefulness: a con-

rmatory factor analysis, MIS Quarterly 17 (4) (1993) 517525.

[39] T. Sun, S. Youn, G.H. Wu, M. Kuntaraporn, Online word-of-mouth (or mouse): an

exploration of its antecedents and consequence, Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication 11 (4) (2006) Article 11.

[40] H. Tajfel, J.C. Turner, The social identity of intergroup behavior, in: S. Worchel,

W.G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations, Nelson Hall, Chicago, IL,

1986.

[41] Y. Tong, X. Wang, H.H. Teo, Understanding the intention of information contribu-

tion to online feedback systems from social exchange and motivation crowding

perspectives, Proceedings of Hawaii International Conference on System Sci-

ences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, Big Island, 2007.

[42] M.M. Wasko, S. Faraj, It is what one does: why people participate and help

others in electronic communities of practice, The Journal of Strategic Information

Systems 9 (2000) 155173.

[43] M.M. Wasko, S. Faraj, Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowl-

edge contribution in electronic networks of practice? MIS Quarterly 29 (1)

(2005) 3557.

[44] B.D. Weinberg, L. Davis, Exploring the WOWin online auction feedback, Journal of

Business Research 58 (11) (2005) 16091621.

Christy M.K. Cheung is Associate Professor at Hong Kong

Baptist University. She received her PhD from City Univer-

sity of Hong Kong. Her research interests include virtual

community, knowledge management, social computing

technology, and IT adoption and usage. Her research arti-

cles have been published in MIS Quarterly, Decision Sup-

port Systems, Information & Management, Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology,

and Information Systems Frontiers. Christy received the

Best Paper Award at the 2003 International Conference

on Information Systems and was the PhD fellow of 2004

ICIS Doctoral Consortium.

Matthew K.O. Lee is Chair Professor of Information Systems

& E-Commerce at the College of Business, City University of

Hong Kong (CityU). Concurrently, he directs the University's

Communication and Public Relations Ofce. Professor Lee's

publications in the information systems and electronic com-

merce areas include a book as well as over one hundred

refereed articles in international journals, conference pro-

ceedings, and research textbooks. He is the Principal Investi-

gator of a number of CERG grants and has published in

leading journals in his eld (such as MIS Quarterly, Journal

of MIS, Communications of the ACM, International Journal

of Electronic Commerce, Decision Support Systems, Infor-

mation & Management, and the Journal of International

Business Studies). His work has received numerous citations in the SCCI/SCI database

and Google Scholar. Professor Lee has served as Associate Editor and Area Editor of the

Journal of Electronic Commerce and Applications (Elsivier Science) and the International

Journal of Information Policy and Law(Inderscience) and served on the editorial board of

the Information Systems Journal (Blackwell Scientic). He has also served as a special

Associate Editor for MIS Quarterly.

8 C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee / Decision Support Systems xxx (2012) xxxxxx

Please cite this article as: C.M.K. Cheung, M.K.O. Lee, What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion

platforms, Decis. Support Syst. (2012), doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.01.015

You might also like

- What Drives Consumers To Spread Electronic Word of Mouth in Online ConsumerDocument8 pagesWhat Drives Consumers To Spread Electronic Word of Mouth in Online Consumerxanod2003No ratings yet

- The Impact of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth Communication: A Literature Analysis and Integrative ModelDocument10 pagesThe Impact of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth Communication: A Literature Analysis and Integrative ModelDaren Kuswadi0% (1)

- Factors Influencing EWOM Effects Using ExperienceDocument7 pagesFactors Influencing EWOM Effects Using ExperienceminhchuyentdNo ratings yet

- Cheung 2009Document31 pagesCheung 2009FábioLimaNo ratings yet

- E-WOM From E-Commerce Websites and Social Media Which Will Consumers AdoptDocument12 pagesE-WOM From E-Commerce Websites and Social Media Which Will Consumers AdoptIndrayana KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Ewom Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesEwom Literature Reviewafmzfgmwuzncdj100% (1)

- The Impact of Perceived e-WOM On Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Corporate ImageDocument12 pagesThe Impact of Perceived e-WOM On Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Corporate ImageUvin RanaweeraNo ratings yet

- Electronic Word-of-Mouth For Online Retailers: Predictors of Volume and ValenceDocument18 pagesElectronic Word-of-Mouth For Online Retailers: Predictors of Volume and ValenceElijah PunzalanNo ratings yet

- Determinants of eWOM Persuasiveness - ALiterature ReviewDocument7 pagesDeterminants of eWOM Persuasiveness - ALiterature ReviewAJHSSR JournalNo ratings yet

- Proposal For MarketingDocument15 pagesProposal For MarketingMuhammad SaqlainNo ratings yet

- Social Capital and Self-Determination Drive eWOM on Social NetworksDocument14 pagesSocial Capital and Self-Determination Drive eWOM on Social NetworkscakryelweNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (eWOM) in Social Networking SitesDocument30 pagesDeterminants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (eWOM) in Social Networking SitesNina CjNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing eWOM: Experience, Credibility, SusceptibilityDocument6 pagesFactors Influencing eWOM: Experience, Credibility, Susceptibilityuki arrownaraNo ratings yet

- The Impact of E-WOM Spread Through Socia PDFDocument5 pagesThe Impact of E-WOM Spread Through Socia PDFMuhammad MuzammalNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (eWOM) in Social Networking SitesDocument30 pagesDeterminants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (eWOM) in Social Networking SitesdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Social eWOM: Does It Affect The Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention of Brands? 1.1 Background of The ProblemDocument6 pagesSocial eWOM: Does It Affect The Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention of Brands? 1.1 Background of The ProblemShahroz AsifNo ratings yet

- E Wom Article1 PDFDocument17 pagesE Wom Article1 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Electronic Word-Of-Mouth: The Moderating Roles of Product Involvement and Brand ImageDocument19 pagesElectronic Word-Of-Mouth: The Moderating Roles of Product Involvement and Brand ImageSiti FatimahNo ratings yet

- The Role of Self-Contrual in Comsumers' eWOM in Social Networking SitesDocument9 pagesThe Role of Self-Contrual in Comsumers' eWOM in Social Networking Sitessarah_alexandra2No ratings yet

- Electronic Word of Mouth Master ThesisDocument7 pagesElectronic Word of Mouth Master Thesisbetsweikd100% (2)

- Computers in Human BehaviorDocument11 pagesComputers in Human BehaviorZameul Islam HamimNo ratings yet

- Ewom: The Effects of Online Consumer Reviews On Purchasing Decision of Electronic GoodsDocument17 pagesEwom: The Effects of Online Consumer Reviews On Purchasing Decision of Electronic Goodsabdul hakimNo ratings yet

- Online Customer Experience: A Review of The Business-to-Consumer Online Purchase ContextDocument16 pagesOnline Customer Experience: A Review of The Business-to-Consumer Online Purchase ContextdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Consumer Attitude Towards Ewom Communication Across Digital ChannelsDocument10 pagesConsumer Attitude Towards Ewom Communication Across Digital ChannelsTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- The in Uence of eWOM in Social Media On Consumers' Purchase Intentions: An Extended Approach To Information AdoptionDocument10 pagesThe in Uence of eWOM in Social Media On Consumers' Purchase Intentions: An Extended Approach To Information AdoptionjazzloveyNo ratings yet

- New Consumer Behavior: A Review of Research On eWOM and HotelsDocument11 pagesNew Consumer Behavior: A Review of Research On eWOM and HotelsDaren KuswadiNo ratings yet

- Ambleebui 2011Document25 pagesAmbleebui 2011lorvina2yna2ramirezNo ratings yet

- Trust Development and Transfer From Electronic Commerce To Social Commerce: An Empirical InvestigationDocument9 pagesTrust Development and Transfer From Electronic Commerce To Social Commerce: An Empirical InvestigationKamal DeepNo ratings yet

- Influence of EWOM On Purchase IntentionsDocument12 pagesInfluence of EWOM On Purchase IntentionsjazzloveyNo ratings yet

- Spreading The Word: How Customer Experience in A Traditional Retail Setting in Uences Consumer Traditional and Electronic Word-Of-Mouth IntentionDocument11 pagesSpreading The Word: How Customer Experience in A Traditional Retail Setting in Uences Consumer Traditional and Electronic Word-Of-Mouth IntentionjareizacmNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media On Consumer Behaviour: Duangruthai Voramontri and Leslie KliebDocument25 pagesImpact of Social Media On Consumer Behaviour: Duangruthai Voramontri and Leslie Kliebvinayak mishraNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Online Customer Reviews - An Interdisciplinary Literature Review and Research AgendaDocument13 pagesAnalyzing Online Customer Reviews - An Interdisciplinary Literature Review and Research AgendaKashif ManzoorNo ratings yet

- Decision Support Systems: Kristine de Valck, Gerrit H. Van Bruggen, Berend WierengaDocument19 pagesDecision Support Systems: Kristine de Valck, Gerrit H. Van Bruggen, Berend WierengaHuong LanNo ratings yet

- 204 453 1 SMDocument9 pages204 453 1 SMMukul KhuranaNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Journal of CommunicationDocument18 pagesMalaysian Journal of Communicationfadli adninNo ratings yet

- Research Paper DP2-1Document13 pagesResearch Paper DP2-1Kiruthika nagarajanNo ratings yet

- Electronic Commerce Research and Applications: SciencedirectDocument9 pagesElectronic Commerce Research and Applications: SciencedirectmelianNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Impact of Social Media On ConsumersDocument18 pagesA Study of The Impact of Social Media On Consumersxueliyan777No ratings yet

- Mehyar, H., Saeed, M., Baroom, H., Aljaafreh, A., & Al-Adaileh, R. M. 'D. (2020)Document12 pagesMehyar, H., Saeed, M., Baroom, H., Aljaafreh, A., & Al-Adaileh, R. M. 'D. (2020)Zhi Jian LimNo ratings yet

- How Information Acceptance Model Predicts Customer Loyalty A Study From Perspective of EWOM InformationDocument14 pagesHow Information Acceptance Model Predicts Customer Loyalty A Study From Perspective of EWOM InformationRAHMAH MEILANY EFENDYNo ratings yet

- Antecedents of Travellers' Electronic Word-Of-Mouth CommunicationDocument24 pagesAntecedents of Travellers' Electronic Word-Of-Mouth CommunicationnaimNo ratings yet

- Impact of eWOM on Online PurchasesDocument20 pagesImpact of eWOM on Online PurchasesAngel DIMACULANGANNo ratings yet

- To What Extent Influences Electronic Word-of-Mouth, in The Field of Music, The Receiver's Purchase Intentions?Document2 pagesTo What Extent Influences Electronic Word-of-Mouth, in The Field of Music, The Receiver's Purchase Intentions?Saisasikanth VanukuriNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Adoption of An Electronic Word of Mouth Message: A Meta-AnalysisDocument34 pagesFactors Affecting The Adoption of An Electronic Word of Mouth Message: A Meta-AnalysisMargaret AshleyNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0278431913001126 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0278431913001126 MainThu ThảoNo ratings yet

- Valck Et Al 2009 - Virtual CommunitiesDocument19 pagesValck Et Al 2009 - Virtual CommunitiesIon_Mihai_8998No ratings yet

- The effect of negative online reviews on consumer attitudesDocument12 pagesThe effect of negative online reviews on consumer attitudesKreunik ArtNo ratings yet

- 103-Phamthiminh-Ly-paperDocument15 pages103-Phamthiminh-Ly-paperHuynh Tan HungNo ratings yet

- INTERNET MARKETING PROJECT PAPER-FinalDocument22 pagesINTERNET MARKETING PROJECT PAPER-FinalJacqueline FarlovNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Online Reviews On HotelDocument14 pagesThe Impact of Online Reviews On Hoteleb060765No ratings yet

- Establishing The Adoption of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Through Consumers' Perceived CredibilityDocument8 pagesEstablishing The Adoption of Electronic Word-of-Mouth Through Consumers' Perceived CredibilitydanikapanNo ratings yet

- Compressed PDF With Cover Page v2Document20 pagesCompressed PDF With Cover Page v2Art CajegasNo ratings yet

- Reupload JournalDocument16 pagesReupload Journalanchu aoiNo ratings yet

- WOM vs E-WOM: Understanding Key DifferencesDocument6 pagesWOM vs E-WOM: Understanding Key DifferencesMahmoud ElshazlyNo ratings yet

- Social Media or Shopping Websites? The Influence of eWOM On Consumers' Online Purchase IntentionsDocument18 pagesSocial Media or Shopping Websites? The Influence of eWOM On Consumers' Online Purchase IntentionsAnissa RachmaniaNo ratings yet

- Bi2010-Study On The Relationship Among Individual Differences E-WOM Perception and Purchase Intention PDFDocument5 pagesBi2010-Study On The Relationship Among Individual Differences E-WOM Perception and Purchase Intention PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- 2Vol98No2 (2)Document12 pages2Vol98No2 (2)Huynh Tan HungNo ratings yet

- SPSS Company Profile - Acquired by IBMDocument4 pagesSPSS Company Profile - Acquired by IBMThe Manual of Ideas100% (2)

- NECF 40days Fast and Pray Booklet 2019Document74 pagesNECF 40days Fast and Pray Booklet 2019Liew2020No ratings yet

- Sweetie's Cookies Business PlanDocument32 pagesSweetie's Cookies Business PlanLiew202080% (41)

- Outstanding Student LetterDocument3 pagesOutstanding Student LettersagarshiroleNo ratings yet

- 2013 PredictionsDocument15 pages2013 PredictionsLiew2020No ratings yet

- Basic Outline of A PaperDocument2 pagesBasic Outline of A PaperMichael MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Example Project CanvasDocument1 pageExample Project CanvasLiew2020No ratings yet

- Designing A Workflow-Based Scheduling Agent With Humans in The LoopDocument12 pagesDesigning A Workflow-Based Scheduling Agent With Humans in The LoopLiew2020No ratings yet

- The Five Love LanguagesDocument7 pagesThe Five Love LanguagesLiew2020No ratings yet

- The Five Love LanguagesDocument7 pagesThe Five Love LanguagesLiew2020No ratings yet

- Psychophysiology and The Five Love LanguagesDocument2 pagesPsychophysiology and The Five Love LanguagesLiew2020No ratings yet

- ReferenceLetters PDFDocument14 pagesReferenceLetters PDFphoeberamosNo ratings yet

- TestDocument1 pageTestLiew2020No ratings yet

- The Future of ITDocument8 pagesThe Future of ITKira LiNo ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- 19 Holiday in Year 2013Document1 page19 Holiday in Year 2013Liew2020No ratings yet

- WP3 0-ErdDocument1 pageWP3 0-ErdLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- WP3 0-ErdDocument1 pageWP3 0-ErdLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned Page PDFDocument1 pageScanned Page PDFLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Fortianalyzer Cli 40 mr3Document312 pagesFortianalyzer Cli 40 mr3Alberto DantasNo ratings yet

- Centrifugal Vs Reciprocating Compressor - Turbomachinery Magazine PDFDocument2 pagesCentrifugal Vs Reciprocating Compressor - Turbomachinery Magazine PDFReyes SanchezNo ratings yet

- Seeing Sounds Worksheet: Tuning Fork StationDocument2 pagesSeeing Sounds Worksheet: Tuning Fork StationEji AlcorezaNo ratings yet

- Advantages of JeepneyDocument3 pagesAdvantages of JeepneyCarl James L. MatrizNo ratings yet

- Main Grandstand - Miro Rivera Architects - EmailDocument16 pagesMain Grandstand - Miro Rivera Architects - Emailmathankumar.mangaleshwarenNo ratings yet

- Refrigerator Frs U20bci U21gaiDocument92 pagesRefrigerator Frs U20bci U21gaiJoão Pedro Almeida100% (1)

- Q603 - Nte159Document2 pagesQ603 - Nte159daneloNo ratings yet

- Operation and Maintenance Manual: COD.: MUM0129 REV. 01Document28 pagesOperation and Maintenance Manual: COD.: MUM0129 REV. 01Laura Camila ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Software Engineering FundamentalsDocument20 pagesSoftware Engineering FundamentalsNâ MííNo ratings yet

- Summarized ResumeDocument2 pagesSummarized Resumeapi-310320755No ratings yet

- Emebbedd Question BankDocument25 pagesEmebbedd Question Banksujith100% (3)

- The Three Main Forms of Energy Used in Non-Conventional Machining Processes Are As FollowsDocument3 pagesThe Three Main Forms of Energy Used in Non-Conventional Machining Processes Are As FollowsNVNo ratings yet

- Locking and Unlocking of Automobile Engine Using RFID1Document19 pagesLocking and Unlocking of Automobile Engine Using RFID1Ravi AkkiNo ratings yet

- Mother Board INTEL D945GNT - TechProdSpecDocument94 pagesMother Board INTEL D945GNT - TechProdSpecVinoth KumarNo ratings yet

- EM100 Training PDFDocument111 pagesEM100 Training PDFAris Bodhi R0% (1)

- Getting Single Page Application Security RightDocument170 pagesGetting Single Page Application Security RightvenkateshsjNo ratings yet

- Odoo 10 DevelopmentDocument123 pagesOdoo 10 DevelopmentTrần Đình TrungNo ratings yet

- Chemical Engineer Skill SetDocument2 pagesChemical Engineer Skill SetJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Atp CucmDocument26 pagesAtp CucmnoumanNo ratings yet

- AlbafixwffDocument7 pagesAlbafixwffjawadbasit0% (1)

- QCL Certification Pvt. LTDDocument3 pagesQCL Certification Pvt. LTDRamaKantDixitNo ratings yet

- Dairy Farm Group Case StudyDocument5 pagesDairy Farm Group Case Studybinzidd007No ratings yet

- Documents - MX DPV Vertical Multistage Pumps 60 HZ Technical Data DP PumpsDocument80 pagesDocuments - MX DPV Vertical Multistage Pumps 60 HZ Technical Data DP PumpsAnonymous ItzBhUGoi100% (1)

- CE132P - Det IndetDocument5 pagesCE132P - Det IndetJanssen AlejoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Otdr Understanding-otdr-po-fop-tm-aePo Fop TM AeDocument1 pageUnderstanding Otdr Understanding-otdr-po-fop-tm-aePo Fop TM AeAgus RiyadiNo ratings yet

- Acceptance Criteria Boiler (API 573)Document1 pageAcceptance Criteria Boiler (API 573)Nur Achmad BusairiNo ratings yet

- Water Overflow Rage and Bubble Surface Area Flux in FlotationDocument105 pagesWater Overflow Rage and Bubble Surface Area Flux in FlotationRolando QuispeNo ratings yet

- IEMPOWER-2019 Conference Dates 21-23 NovDocument2 pagesIEMPOWER-2019 Conference Dates 21-23 Novknighthood4allNo ratings yet

- BS WaterDocument0 pagesBS WaterAfrica OdaraNo ratings yet

- Cyber Security and Reliability in A Digital CloudDocument95 pagesCyber Security and Reliability in A Digital CloudBob GourleyNo ratings yet