Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Van Der Heijden, Verhagen, Creemers - 2003 - Understanding Online Purchase Intentions Contributions From Technology and Trust Perspectiv

Uploaded by

Liew20200 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

86 views8 pagesVan Der Heijden, Verhagen, Creemers - 2003 - Understanding Online Purchase Intentions Contributions From Technology and Trust Perspectiv

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentVan Der Heijden, Verhagen, Creemers - 2003 - Understanding Online Purchase Intentions Contributions From Technology and Trust Perspectiv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

86 views8 pagesVan Der Heijden, Verhagen, Creemers - 2003 - Understanding Online Purchase Intentions Contributions From Technology and Trust Perspectiv

Uploaded by

Liew2020Van Der Heijden, Verhagen, Creemers - 2003 - Understanding Online Purchase Intentions Contributions From Technology and Trust Perspectiv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

Understanding online purchase intentions:

contributions from technology and trust

perspectives

Hans van der Heijden

1

,

Tibert Verhagen

1

and

Marcel Creemers

1

1

Department of Information Systems, Marketing,

and Logistics, Faculty of Economics and

Business Administration, Vrije Universiteit

Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Correspondence:

Hans van der Heijden, Department of

Information Systems, Marketing, and

Logistics, Faculty of Economics and Business

Administration, Vrije Universiteit

Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1105, 1081 HV

Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Tel: +31 20 444 6050;

Fax: +31 20 444 6005;

E-mail: hheijden@feweb.vu.nl

Received: 12 July 2000

Revised: 20 August 2001

: 30 July 2002

Accepted: 15 October 2002

Abstract

This paper explores factors that influence consumers intentions to purchase

online at an electronic commerce website. Specifically, we investigate online

purchase intention using two different perspectives: a technology-oriented

perspective and a trust-oriented perspective. We summarise and review the

antecedents of online purchase intention that have been developed within

these two perspectives. An empirical study in which the contributions of both

perspectives are investigated is reported. We study the perceptions of 228

potential online shoppers regarding trust and technology and their attitudes

and intentions to shop online at particular websites. In terms of relative

contributions, we found that the trust-antecedent perceived risk and the

technology-antecedent perceived ease-of-use directly influenced the attitude

towards purchasing online.

European Journal of Information Systems (2003) 12, 4148. doi:10.1057/

palgrave.ejis.3000445

Introduction

The research objective of this paper is to explore the factors that in-

fluence online purchase intentions in consumer markets. Firms operating

in this segment sell their goods and services to consumers via a web-

site. These online stores are important and sometimes highly visible

representatives of the new economy, yet despite this, they do not enjoy

much sound conceptual and empirical research (Hoffman & Novak, 1996;

Alba et al., 1997). An increased understanding of online consumer

behaviour can benefit them in their efforts to market and sell products

online.

We investigate consumers intentions to purchase products at on-

line stores using two different perspectives: a technology-oriented

perspective and a trust-oriented perspective. Technology and trust issues

are highly relevant to online consumer behaviour, yet their inclusion in

traditional consumer behaviour frameworks is limited. We discuss the

contributions of each perspective to our understanding of online purchase

intentions. We also present an empirical study that examines the

contribution of each perspective by surveying 228 potential online

shoppers.

The paper is organised as follows. First, we deal with the theoretical

background, paying attention to technology and trust-oriented perspec-

tives of online consumer behaviour. The subsequent section deals with the

empirical study. Next, we present a summary of the findings. We conclude

with a discussion and further directions for research.

European Journal of Information Systems (2003) 12, 4148

& 2003 Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. All rights reserved 0960-085X/03 $25.00

www.palgrave-journals.com/ejis

Theory

To a very large extent, online consumer behaviour can be

studied using frameworks from offline or traditional

consumer behaviour. A number of general frameworks in

consumer behaviour are available that capture the

decision-making processes of consumers (Engel et al.,

1995; Schiffman & Kanuk, 2000). These frameworks

distinguish a number of stages, typically including at

least the following: need recognition, prepurchase search,

evaluation of alternatives, the actual purchase, and

postpurchase evaluation. These stages are relatively

abstract and do not consider the medium through which

the consumer buys. Hence, the stages can be applied to

online consumer behaviour (OKeefe & McEachern,

1998).

Looking more closely at the difference between online

and off-line consumer behaviour, we can identify at

least two types of issues that differentiate online

consumers from off-line consumers. First, online con-

sumers have to interact with technology to purchase the

goods and services they need. The physical shop

environment is replaced by an electronic shopping

environment or, in other words, by an information

system (IS). This gives rise to technical issues that have

traditionally been the domain of IS and human computer

interaction (HCI) researchers (OKeefe et al., 2000).

Second, a greater degree of trust is required in an online

shopping environment than in a physical shop. It is by

now a folk theorem that trust is an important issue for

those who engage in electronic commerce (Keen et al.,

1999). Trust mitigates the feelings of uncertainty that

arise when the shop is unknown, the shop owners are

unknown, the quality of the product is unknown, and

the settlement performance is unknown (Tan & Thoen,

2001). These conditions are likely to arise in an electronic

commerce environment.

Given these differences, research in online consumer

behaviour can benefit from models that have been

developed to study technology and trust issues in

particular. We will examine the contributions of each of

these models in more detail in the following sections.

Contributions from technology-oriented models

The technology perspective focuses on the consumers

assessment of the technology required to conduct a

transaction online. In the context of this paper, technol-

ogy refers to the website that an online store employs to

market and sell its products. Researchers have long been

studying how consumers search for information about

products and how useful technology can be to acquire

this information (Stigler, 1961; Thorelli & Engledow,

1980; Keller & Staelin, 1987; Widing & Talarzyk, 1993;

Moorthy et al., 1997). Information-seeking behaviour by

consumers is characterised by a trade-off between the cost

of searching and evaluating more alternative products

and the benefit of a better decision when more alter-

natives are taken into account (Hauser & Wernerfelt,

1990). Technology has the potential to both decrease the

cost of searching and evaluating alternatives and increase

the quality of the decision (Haubl & Trifts, 2000).

The advent of the internet and the proliferation of

online stores have given rise to a number of studies that

look at the consumers intention to purchase online.

There is some evidence that online consumers not only

care for the instrumental value of the technology, but

also the more immersive, hedonic value (Childers et al.,

2001; Heijden, forthcoming). These and other studies

(Chau et al., 2000) build their models upon a well-known

theory in IS research: the technology acceptance model

(TAM).

The TAM was first developed by Davis to explain user

acceptance of technology in the workplace (Davis, 1989;

Davis et al., 1989). TAM adopts a causal chain of beliefs,

attitudes, intention, and overt behaviour that social

psychologists Fishbein and Ajzen (Fishbein & Ajzen,

1975; Ajzen, 1991) have put forward, and that has

become known as the Theory of Reasoned Action

(TRA). Based on certain beliefs, a person forms an attitude

about a certain object, on the basis of which he/she forms

an intention to behave with respect to that object. The

intention to behave is the prime determinant of the

actual behaviour.

Davis adapted the TRA by developing two key beliefs

that specifically account for technology usage. The first of

these beliefs is perceived usefulness, defined by Davis as

the degree to which a person believes that using a

particular system would enhance his or her job perfor-

mance. The second is perceived ease-of-use, defined as the

degree to which a person believes that using a particular

system would be free of effort. Moreover, TAM theorises

that all other external variables, such as system-specific

characteristics, are fully mediated by these two key

beliefs. The model has recently been updated (Venkatesh

& Davis, 2000) with a number of antecedents of

usefulness and ease-of-use, including subjective norms,

experience, and output quality. There is ample evidence

that not only usefulness (i.e., external motivation) but

also enjoyment (i.e., internal motivation) is a direct

determinant of user acceptance of technology (Davis et

al., 1992; Venkatesh, 1999). This is in line with a recent

evaluation of the TRA, in recognition of the evidence that

attitudes are not only based on cognition, but also on

affection (Ajzen, 2001). Viewed in this light, perceived

usefulness and ease-of-use represent the cognitive com-

ponent of the user evaluation, while perceived enjoy-

ment represents the affective component.

Researchers have empirically validated the original

TAM in a variety of settings. Of particular interest here

are recent studies on technology acceptance in internet

usage and website usage. These studies by and large

confirm the relevance and appropriateness of ease-of-use

and usefulness in an online context, and find substantial

evidence for the intrinsic enjoyment that many con-

sumers have when surfing the web (Teo et al., 1999;

Lederer et al., 2000; Moon & Kim, 2001). Support has also

been found for ease-of-use being an antecedent of

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 42

European Journal of Information Systems

usefulness and perhaps not directly contributing to

attitude formation (Gefen & Straub, 2000).

Summarising, the contribution of TAM and other

similar models is that they explain why online transac-

tions are conducted from a technological point of view.

In doing so, they highlight the importance of website

usefulness and the usability of the website. Also, these

models direct our attention to the hedonic features of the

technology and demonstrate how these features can

affect consumers intention to purchase online.

Contributions from trust-oriented models

The trust-oriented perspective quickly gained momen-

tum after the introduction of wide-scale electronic

commerce in the beginning of the 1990s (Keen et al.,

1999). Trust is a multidimensional concept that can be

studied from the viewpoint of many disciplines, includ-

ing social psychology, sociology, economics, and market-

ing (Doney & Cannon, 1997). While there are many

definitions of trust, the one that we will adopt in this

paper is the willingness of a consumer to be vulnerable to

the actions of an online store based on the expectation

that the online store will perform a particular action

important to the consumer, irrespective of the ability to

monitor or control the online store cf. the more general

definition from Mayer et al. (1995).

While researchers have been concerned with interper-

sonal trust and inter-organisational trust, they have paid

less attention to trust between people and organisations

(Lee & Turban, 2001). Recent conceptual and empirical

research has started to look into this type of trust in more

detail, in particular in the context of business to

consumer electronic commerce. Researchers have devel-

oped instruments to measure trust in internet shopping

(Cheung & Lee, 2000; Jarvenpaa et al., 2000), and these

measures are beginning to be used in the testing of

empirical frameworks.

To what extent does trust in the company influence the

intention to buy at a specific website? The existing

empirical evidence suggests that trust in the company

negatively influences the perceived risk that is associated

with buying something on the internet (Featherman,

2001; Pavlou, 2001). Perceived risk can be regarded as a

consumers subjective function of the magnitude of

adverse consequences and the probabilities that these

consequences may occur if the product is acquired

(Dowling & Staelin, 1994). The more a person trusts the

internet company, the less the person will perceive risks

associated with online buying. Perceived risk, in turn,

negatively influences the attitude towards internet shop-

ping. Trust in the online store may also directly influence

this attitude (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000).

People develop trust in the webstore through a number

of factors. One is the perceived size of the company,

another is their reputation (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000). The

larger the perceived size and the perceived reputation, the

greater the trust in the company. Reputation is closely

relaled to familiarity with the store, which researchers

have also identified as an antecedent of trust. Familiarity

deals with an understanding of current actions of the

store, while trust deals with beliefs about the future

actions of other people (Gefen, 2000).

It should be noted that trust in the company does not

have to be a necessary condition to purchase online. It

has been argued that lack of trust in the organisation can

be offset by trust in the control system (Tan & Thoen,

2001). Such a control system would include the proce-

dures and protocols that monitor and control the

successful performance of a transaction, and could

include the option to insure oneself against damage.

We may not trust the internet company, but we may trust

the control system that monitors its performance (Tan &

Thoen, 2002).

In sum, the trust-oriented perspective highlights the

importance of trust in determining online purchase

intentions, and its antecedents include a number of trust

drivers. In doing so, it emphasises constructs such as

perceived risk, trust in the online store, perceived size,

and perceived reputation.

Method

To explore the contributions and the relative importance

of each perspective, we conducted an empirical study.

The following sections describe the model, the measure-

ment instrument, and the sample.

Conceptual model

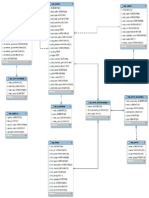

The model that we attempted to test is depicted in

Figure 1. The backbone of this model is the relation

between attitude towards online purchasing and inten-

tion to purchase online. This conforms the general

relation between attitudes and intentions that the theory

of reasoned action predicts, and is consistent with prior

online purchase models (Jarvenpaa et al., 2000; Pavlou,

2001).

The attitude construct has four antecedents in total:

two from the technology perspective and two from the

trust perspective. The technological antecedents are the

perceived usefulness and perceived ease-of-use. Both

constructs originate from TAM. The trust antecedents

are trust in the online store and perceived risk; these

constructs appear in the Jarvenpaa et al. study. Signs and

directions of the relations between the constructs are

displayed in Figure 1 and have been discussed in the

Theory section.

Measurement instrument

In order to increase reliability and ease of comparison

with previous work in this area, we operationalised each

construct with multiple items. The operationalisations

for the trust constructs were taken from Jarvenpaa et al.

(2000). The operationalisations for the usefulness con-

structs were taken from Chau et al. (2000), based on Davis

(1989). We made modifications, most of which were

adaptations to increase the applicability of the items to

the local context. A substantial adaptation involved the

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 43

European Journal of Information Systems

replacement of the word Internet with This website to

increase consistency in the unit of analysis for each

construct (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; DeVellis, 1991). Also,

we changed the wording of the ease-of-use and usefulness

items to make them more suitable for e-commerce

websites. The resulting items can be found in the

Appendix.

Sample

Our sample consisted of a group of undergraduate

students who enrolled for a mandatory IS course at a

Dutch academic institution. Each student was notified in

class of the survey, and invited to participate for partial

class credit.

Before the subjects started the survey, their task was to

study two specific websites carefully. The first one was the

website of a pure player CD store: this website was a

newcomer to the Dutch CD market and sold its products

only over the internet. The second one was the website of

a bricks-n-clicks CD store. This website represented a

large and well-known chain of CD stores in the Nether-

lands. Like the first online store, the websites purpose

was to sell CDs directly over the internet.

After the students had studied the websites, they were

asked to complete a survey for each website. Respondents

returned the questionnaires both at home and on

campus. It was possible to submit the responses through

the internet or return them handwritten.

Results

Eventually, 228 students took part in the survey. Table 1

provides information on their internet experience and

their experience with online shopping.

As the profile data show, this group is relatively

homogeneous in terms of age and balanced in terms of

internet experience. The gender balance in the current

sample is similar to the gender balance of the entire

population of internet users (Kehoe et al., 1999). The

online purchase experience of the respondents is hetero-

geneous, and this reveals a large set of inexperienced

online purchasers and a small set of very experienced

online purchasers.

Reliability and validity

We used Cronbachs a and exploratory factor analysis to

examine the reliability and unidimensionality of each

construct. Passing of these tests is a prerequisite for

further analysis (Nunally, 1967; DeVellis, 1991). To obtain

acceptable values, we modified the trust and perceived

risk scales, in line with the modifications that Jarvenpaa

Figure 1 Conceptual model (adapted from Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Davis, 1989; Jarvenpaa et al., 2000).

Table 1 Profile of respondents sample (N=228)

Question Count Percentage

Age (years)

1920 85 37

2122 83 36

2324 39 17

X25 20 9

Missing 1

Gender

Male 164 72

Female 64 28

Years of experience with the Internet

None 0 0

1 year 16 7

2 years 59 26

3 years 75 33

4 years or more 77 34

Missing 1

Number of times product bought on the internet

None 149 66

Once 33 14

Twice 18 8

Three times 6 3

Four times or more 20 9

Missing 2

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 44

European Journal of Information Systems

et al made (see the appendix for the exact changes).

Table 2 displays the resulting a coefficients for each of the

constructs and for each of the websites. All resulting

scales are unidimensional and sufficiently reliable.

We estimated the models parameters using the scales

and structural equation modelling (SEM). The goodness-

of-fit measures, depicted in Table 3, show good fit with

the data and consequently, we can proceed with an

analysis of the path parameters.

Figure 2 displays the path coefficients that the

SE package has estimated, along with the squared multi-

ple correlations of the intermediate and dependent

variables.

The data supported a strong positive relation between

attitude towards online purchasing and intention

to purchase online. The only predictor of attitude

that was significant in both cases was the perceived

risk. Perceived ease-of-use was a significant predictor

only in the case of the bricks-n-clicks online store. The

relation between trust and risk and the relation between

perceived ease-of-use and perceived usefulness were

supported.

Discussion

The result of this research suggests that perceived risk and

perceived ease-of-use are antecedents of attitude towards

online purchasing. The effect of perceived risk was

strongly negative in both cases, and the effect of

perceived ease-of-use was positive in one case. The data

did not support a positive effect from trust in the online

store and from the perceived usefulness of the website.

Trust in store appears to be indirectly related to a positive

attitude through its direct negative effect of perceived

risk. In sum, contributions from both the trust perspec-

tive and the technology perspective could be found,

although the contribution of the technology perspective

appears to be less.

Our results are only partly in line with other TAM

studies. The impact of perceived ease-of-use on perceived

usefulness is in line with earlier research. The lack of

effect of perceived usefulness and perceived ease-of-use

on attitudes towards online purchasing is not. One

explanation for this result is that the dependent variables

of our study are narrower in scope to the ones commonly

found in TAM models. TAM models focus on usage

intention of the technology, as opposed to purchase

intention. In an e-commerce context, usage intention is

broader in scope than purchase intention. This is because

a person may use an online store not only to purchase,

but also to learn about products and services. Hence,

respondents do not intend to purchase items at the

online store, even though they perceive the store as

useful.

A second, related explanation is that in retrospect

perceived usefulness may have been too narrowly

operationalised. For example, speed and convenience

are included in the scale, but perceptions about the price

levels of the online store are not. A more detailed

assessment of the perceived usefulness of online

stores may reveal more appropriate items. Perhaps,

our operationalisation failed to tap salient aspects

of usefulness, and in doing so tampered its predictive

value.

It is interesting to compare the results from this

study to the study from Jarvenpaa et al. This study looked

at the impact of trust and perceived risk in a

similar empirical setting. Our results partly corroborate

their findings. We did find a positive effect of trust in

the store on perceived risk, and an effect of perceived

risk on the attitude towards online purchasing. In

contrast, we did not find any effect of trust in the store

on attitude.

How can these differences be explained? Why

were trust, ease-of-use, and usefulness not significant

in our study, even though previous research has found

empirical support for them? We believe it is conceivable

that trust, ease-of-use, and usefulness are threshold

variables. This means that once a certain evaluation

level is reached, the variable no longer contributes to

Table 2 Reliability coefficients for each construct

Number of

items

Pure player

(n 218)

Bricks-n-clicks

(n 212)

Trust in store 3 0.69 0.79

Risk 3 0.80 0.80

Ease-of-use 5 0.87 0.95

Usefulness 3 0.80 0.84

Attitude 3 0.92 0.93

Intention 4 0.91 0.92

Table 3 Goodness-of-fit values

Goodness-of-fit measure Acceptable values (Hair et al., 1998) Pure player Bricks-n-clicks

w

2

NS 285 ( po0.001) 275 ( po0.001)

RMSEA o 0.08 0.05 0.05

GFI No established threshholds (the higher the better) 0.90 0.89

NFI 0.90 0.90 0.93

TLI 0.90 0.96 0.97

RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; GFI, goodness-of-fit index; NFI, normed fit index; TLI, TuckerLewis index.

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 45

European Journal of Information Systems

a favourable attitude. Hence, these variables affect

attitudes only on low evualation levels, that is, when

respondents evaluate them as being poor. A shopper may

or may not purchase at a trustworthy website, but he/she

will definitely not purchase at an untrustworthy site.

A shopper may or may not purchase at a user-friendly

website, but he or she will definitely not purchase at an

user-unfriendly website.

This line of reasoning suggests another explanation of

our findings: we did not select websites where trust in the

store, ease-of-use, and usefulness were poorly evaluated.

Indeed, the three no-effect constructs (trust, perceived

usefulness, and perceived ease-of-use) received high

evaluations from the respondents. While the unbridled

trust in the pure player may seem odd in hindsight, the

reader should keep in mind that the survey was

administered at a time when stock exchanges and

investors were still euphoric about internet start-ups.

We also observed that the two websites appeared to be

well designed and offered efficient online purchasing

facilities. So, we speculate that trust, perceived usefulness,

and perceived ease-of-use reached threshold levels in

many of the respondents minds and this is why they did

not generate any effect on their attitudes towards

purchasing online.

Our conceptualisation of these constructs as threshold

variables borrows from Herzbergs research on hygiene and

motivational factors in the area of job satisfaction.

Herzberg theorised that some factors influence job

satisfaction but not dissatisfaction (achievement, recog-

nition), while others only influenced job dissatisfaction

but not satisfaction (salary, relationship with supervisor).

The former ones are called motivational factors, the latter

hygiene factors (Herzberg et al., 1959). Similar to this line

of reasoning, it is possible that some or all of the

antecedents in our model are hygiene factors. In other

words, perceived risk, trust in the store, perceived

usefulness, and perceived ease-of-use negatively influence

an unfavourable attitude towards online purchasing, but

do not positively influence a favourable attitude towards

online purchasing.

Clearly, this threshold hypothesis requires further

theoretical and empirical analysis, because it requires

the conceptualisation of two separate attitudes (one

favourable, one unfavourable). Further research may shed

additional light on why antecedents appear to influence

online consumer behaviour in some studies, but not in

other studies.

An important limitation of our empirical study is

the relatively large proportion of inexperienced online

shoppers. While we are confident that our findings

extend to other populations with the same profile,

the generalisibility of the results to larger, more

experienced populations is limited. For this reason,

we encourage other researchers to replicate and extend

our study in settings with more experienced online

shoppers.

Online consumer behaviour is a broad area of study,

and we realise that our research has only investigated

a modest part of this area. Besides further exploration

of the threshold hypothesis, a promising direction

of further research is the extent to which technology

itself helps to build trust. This calls for an interesting

mixture of both perspectives. For example, it is defen-

sible to argue that a websites design can increase

a consumers confidence, much like a good interior

design in a restaurant can promote confidence in the

quality of the forthcoming food. In doing so, the

technology can increase a persons trust in the store. A

related subject is the degree to which specific website

features help bolster trust. Are third party assurance seals

and certifications of any importance? Do testimonials

from consumers, or a personal note from the shop owner

increase trust? To what extent, and under which condi-

tions? We encourage other researchers to examine these

subjects further.

Figure 2 SEM estimation results. Standardised path coefficients are significant at po0.005 except otherwise noted. Normal font

represents values of the pure player online store, italics font represents values of the bricks-n-clicks player. Percentages indicate

squared multiple correlations (variance explained).

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 46

European Journal of Information Systems

References

AJZEN I (1991) The theory of planned behaviour. Organisational Behaviour

and Human Decision Processes 50, 179211.

AJZEN I (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of

Psychology 52, 2758.

AJZEN I and FISHBEIN M (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting

Social behaviour. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

ALBA J, LYNCH J et al. (1997) Interactive home shopping: consumer

retailer, and manufacturer incentives to participate in electronic

marketplaces. Journal of Marketing 61, 3853.

CHAU PYK, AU G et al. (2000) Impact of information presentation modes

on online shopping: an empirical evaluation of a broadband

interactive shopping service. Journal of Organisational Computing and

Electronic Commerce 10(1), 122.

CHEUNG C and LEE MKO (2000) Trust in Internet Shopping: A Proposed

Model and Measurement Instrument. American Conference on Informa-

tion Systems, Long Beach.

CHILDERS TL, CARR CL et al. (2001) Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for

online retail shopping behaviour. Journal of Retailing 77, 511535.

DAVIS FD. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user

acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly 13(3), 319340.

DAVIS FD, BAGOZZI RP et al. (1989) User acceptance of computer

technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management

Science 35(8), 9831003.

DAVIS FD, BAGOZZI RP et al. (1992) Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to

use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology

22, 11111132.

DEVELLIS RF. (1991) Scale Development. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

DONEY PM and CANNON JP (1997) An examination of the nature of

trust in buyerseller relationships. Journal of Marketing 61(4),

3551.

DOWLING GR and STAELIN R (1994) A model of perceived risk and intented

risk-handling activity. Journal of Consumer Research 21, 119134.

ENGEL JF, BLACKWELL RD et al. (1995) Consumer Behavior. Dryden, Forth

Worth.

FEATHERMAN MS. (2001) Extending the Technology Acceptance Model by

Inclusion of Perceived Risk. American Conference on Information

Systems, Boston.

FISHBEIN M and AJZEN I. (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An

Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, M.A.

GEFEN D. (2000). E-commerce: the role of familiarity and trust. Omega

28, 725737.

GEFEN D and STRAUB D (2000) The relative importance of perceived ease

of use in IS adoption: a study of e-commerce adoption. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems 1(8), 130.

HAIR JF, ANDERSON RE et al. (1998) Multivariate Data Analysis. Prentice-

Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

HAUBL G and TRIFTS V. (2000) Consumer decision making in online

shopping environments: the effects of interactive decision aids.

Marketing Science 19(1), 421.

HAUSER JR, WERNERFELT B (1990) An evaluation cost model of considera-

tion sets. Journal of Consumer Research 16, 393408.

HEIJDEN Hvd (forthcoming) Factors influencing the usage of websites: the

case of a generic portal in the Netherlands. Information & Manage-

ment.

HERZBERG F, MAUSNER B et al. (1959) The Motivation to Work. John Wiley,

New York.

HOFFMAN DL and NOVAK TP (1996) Marketing in hypermedia computer-

mediated environments: conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing

60, 5068.

JARVENPAA SL, TRACTINSKY N et al. (2000) Consumer trust in an internet

store. Information Technology & Management 1(1), 4571.

KEEN P, BALLANCE C et al. (1999) Electronic Commerce Relationships: Trust

By Design. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

KEHOE C, PITKOW J et al. (1999) Results of GVUs Tenth World Wide Web

User Survey. http://www.gvu.gatech.edu/gvu/user_surveys/survey-

1998-10/tenthreport.html, viewed 24 July 2001.

KELLER KL and STAELIN R (1987) Effects of quality and quantity of

information on decision effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research 14,

200213.

LEDERER AL, MAUPIN DJ et al. (2000) The technology acceptance model

and the World Wide Web. Decision Support Systems 29, 269282.

LEE MKO and TURBAN E (2001) A trust model for consumer

internet shopping. International Journal of Electronic Commerce 6(1),

7591.

MAYER RC, DAVIS JH et al. (1995) An integrative model of organizational

trust. Academy of Management Review 20(3), 709734.

MOON J-W and KIM Y-G. (2001) Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-

Web context. Information & Management 38, 217230.

MOORTHY S, RATCHFORD BT et al. (1997) Consumer information search

revisited: theory and empirical analysis. Journal of Consumer Research

23, 263277.

NUNALLY J. (1967) Psychometric Theory. Mc-Graw Hill, New York.

OKEEFE B and MCEACHERN T (1998) Web-based customer decision

support systems. Communications of the ACM 41(3), 7178.

OKEEFE RM, COLE M et al. (2000) From the user interface to the consumer

interface: results from a global experiment. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies 53, 611628.

PAVLOU PA. (2001) Integrating Trust in Electronic Commerce with the

Technology Acceptance Model: Model Development and Validation.

American Conference on Information Systems, Boston.

SCHIFFMAN LG and KANUK LL. (2000) Consumer Behavior. Prentice-Hall,

Upper Saddle River, NJ.

STIGLER G. (1961) The economics of information. Journal of Political

Economy 69, 213225.

TAN Y-H and THOEN W. (2001) Toward a generic model of trust for

electronic commerce. International Journal of Electronic Markets 5(2),

6174.

TAN Y-H, THOEN W (2002) Formal aspects of a generic model of trust for

electronic commerce. Decision Support Systems 33, 233246.

TEO TSH, LIM VKG et al. (1999) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in

Internet usage. Omega: International Journal of Management Science

27, 2537.

THORELLI HB and ENGLEDOW JL (1980) Information seekers and

information systems: a policy perspective. Journal of Marketing 44,

927.

VENKATESH V (1999) Creation of favorable user perceptions: exploring the

role of intrinsic motivation. MIS Quarterly 23(2), 239260.

VENKATESH V and DAVIS FD (2000) A theoretical extension of the

Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal case studies.

Management Science 46(2), 186204.

WIDING RE and TALARZYK WW. (1993) Electronic information systems

for consumers: an evaluation of computer-assisted formats in

multiple decision environments. Journal of Marketing Research 30,

125141.

Appendix

All items were measured on a seven point Likert strongly

disagree/strongly agree scale, unless mentioned other-

wise.

Trust in store

w

1. This store is trustworthy

2. This store wants to be known as one who keeps his

promises (modified).**

3. I trust this store keeps my best interests in mind.

4. I think it makes sense to be cautious with this store

(modified)(reverse).*

5. This retailer has more to lose than to gain by not

delivering on their promises.*

,

**

6. This stores behaviour meets my expectations.*

,

**

7. This store could not care less about servicing stu-

dents*

,

** (modified) (reverse).

w

* Indicates dropped item by Jarvenpaa et al. (2000); **

indicates dropped item in our own research, modified

indicates adaptations from original work

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 47

European Journal of Information Systems

Attitude towards online purchasing

1. The idea of using this website to buy a product of

service is appealing (modified).

2. I like the idea of buying a product or service on this

website (modified).

3. Using this website to buy a product or service at this

store would be a good idea (modified).

Online purchase intention

1. How likely is it that you would return to this stores

website?

2. How likely is it that you would consider purchasing

from this website in the short term? (modified).

3. How likely is it that you would consider purchasing

from this website in the longer term? (modified).

4. For this purchase, how likely is it that you would buy

from this store?*

Risk perception

1. How would you characterise the decision to buy a

product through this website? (a very small risk a

very big risk).**

2. How would you characterise the decision to buy a

product through this website? (high potential for loss

high potential for gain)(reverse).

3. How would you characterise the decision to buy a

product through this website? (a very negative situa-

tion a very positive situation) (reverse).

4. What is the likelihood of your making a good bargain

by buying from this store through the Internet? (very

unlikely very likely) (reverse).

Ease-of-use

1. Learning to use the website is easy.

2. It is easy to get the website to do what I want.

3. The interactions with the website are clear and

understandable.

4. The website is flexible to interact with.

5. The website is easy to use.

Usefulness

1. The online purchasing process on this website is fast.

2. It is easy to purchase online on this website.

3. This website is useful to buy the products or services

they sell.

Understanding on-line purchase intentions Hans van der Heijden et al 48

European Journal of Information Systems

You might also like

- Rujukan 1 NewDocument2 pagesRujukan 1 NewWinarniNo ratings yet

- Jurnal InternasionalDocument36 pagesJurnal Internasionalasmarini syamNo ratings yet

- 07 Chapter 2Document42 pages07 Chapter 2Chirag MalankiyaNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Role of Trust in Online Shopping Intention For Consumer Electronics ProductsDocument12 pagesUnderstanding The Role of Trust in Online Shopping Intention For Consumer Electronics ProductsrajisumaNo ratings yet

- 9086-Article Text-35291-1-10-20150126 PDFDocument16 pages9086-Article Text-35291-1-10-20150126 PDFalibaba1888No ratings yet

- Journal - 3 1 9Document9 pagesJournal - 3 1 9sengottuvelNo ratings yet

- Exploring Factors That Affect Usefulness, Ease of Use, Trust, and Purchase Intention in The Online Environment PDFDocument16 pagesExploring Factors That Affect Usefulness, Ease of Use, Trust, and Purchase Intention in The Online Environment PDFMulawarman Guesthouse BaliNo ratings yet

- Determiners of Consumer Trust Towards Electronic Commerce: An Application To Puerto RicoDocument24 pagesDeterminers of Consumer Trust Towards Electronic Commerce: An Application To Puerto RicoMARIA SALEEMNo ratings yet

- Journal of Business Research: Blanca Hernández, Julio Jiménez, M. José MartínDocument8 pagesJournal of Business Research: Blanca Hernández, Julio Jiménez, M. José MartínHoàng Anh HồNo ratings yet

- Shailendra Singh - Online Buying BehaviourDocument9 pagesShailendra Singh - Online Buying BehaviourSree LakshyaNo ratings yet

- E-Consumer BehaviourDocument15 pagesE-Consumer BehaviourfelipelozadagNo ratings yet

- Purchasing Behavior, TurkeyDocument22 pagesPurchasing Behavior, TurkeyKavya GopakumarNo ratings yet

- 03 Literature ReviewDocument7 pages03 Literature Reviewsai venkatNo ratings yet

- Consumers' Behavioral Intention To Use Internet Shopping: An Integrated Model of TAM and TRADocument19 pagesConsumers' Behavioral Intention To Use Internet Shopping: An Integrated Model of TAM and TRAFatima NadeemNo ratings yet

- An Exploratory Study of Consumer Adoption of Online Shopping - MedDocument16 pagesAn Exploratory Study of Consumer Adoption of Online Shopping - MedDix TyNo ratings yet

- 8541-Article Text-33891-1-10-20140423 PDFDocument6 pages8541-Article Text-33891-1-10-20140423 PDFkitape tokoNo ratings yet

- The Propensity of E-Commerce Usage The Influencing VariablesDocument25 pagesThe Propensity of E-Commerce Usage The Influencing VariablesMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- Which Is More Important in Internet Shopping: Perceived Price or Trust?Document12 pagesWhich Is More Important in Internet Shopping: Perceived Price or Trust?Anderson TrindadeNo ratings yet

- 19 Shu-Hung HsuDocument10 pages19 Shu-Hung HsuKaranJoharNo ratings yet

- Customer Behavior in Electronic Commerce: The Moderating Effect of E-Purchasing ExperienceDocument10 pagesCustomer Behavior in Electronic Commerce: The Moderating Effect of E-Purchasing ExperienceAbhishek DhimanNo ratings yet

- ArmDocument5 pagesArmMahrukh SaeedNo ratings yet

- Influence of EWOM On Purchase IntentionsDocument12 pagesInfluence of EWOM On Purchase IntentionsjazzloveyNo ratings yet

- E-Tailers Versus Retailers Which Factors Determine Consumer PreferencesDocument11 pagesE-Tailers Versus Retailers Which Factors Determine Consumer Preferencesnyank_21No ratings yet

- Web design elements impact online purchase intentionDocument17 pagesWeb design elements impact online purchase intentionرهيب صادق النظيفNo ratings yet

- Consumers Online Information Search Behavior andDocument14 pagesConsumers Online Information Search Behavior andarunima.rana88No ratings yet

- E-Shopping: An Extended Technology Innovation: Varsha Agarwal, Ganesh LDocument8 pagesE-Shopping: An Extended Technology Innovation: Varsha Agarwal, Ganesh LtalktoyeshaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Youngsters' Attitude Towards Online ShoppingDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Youngsters' Attitude Towards Online ShoppingMayur PatelNo ratings yet

- Consumer BehaviorDocument39 pagesConsumer BehaviorSittie Hana Diamla SaripNo ratings yet

- Group 1 (Emilio Jacinto)Document36 pagesGroup 1 (Emilio Jacinto)Clea Marie Donaira Mendoza CilloNo ratings yet

- Perceptions Towards Online Shopping: Analyzing The Greek University Students' AttitudeDocument13 pagesPerceptions Towards Online Shopping: Analyzing The Greek University Students' Attituderavneet20saraoNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Consumer Decisions in Virtual ShoppingDocument17 pagesFactors Influencing Consumer Decisions in Virtual Shoppingsfgoe wksdfNo ratings yet

- A Review of Factors Affecting Online BuyDocument16 pagesA Review of Factors Affecting Online BuySunjida EnamNo ratings yet

- Chapter-2: 2.1 National Review of LitreatureDocument7 pagesChapter-2: 2.1 National Review of Litreatureshubham bhosleNo ratings yet

- Online Purchase IntentionDocument10 pagesOnline Purchase IntentionHoàng Lan TrầnNo ratings yet

- Digital Consumer Behaviour in Cyprus: From Uses and Gratifications Theory To 4C's Online Shopping ApproachDocument11 pagesDigital Consumer Behaviour in Cyprus: From Uses and Gratifications Theory To 4C's Online Shopping ApproachTasha AuliaNo ratings yet

- A CriticalDocument12 pagesA CriticalFahri Muhammad RidwanNo ratings yet

- Influencing The Online Consumer's Behavior: The Web ExperienceDocument17 pagesInfluencing The Online Consumer's Behavior: The Web ExperienceAnbuoli ParthasarathyNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Driving Factors That Influence Continuance Online ShoppingDocument13 pagesUnderstanding The Driving Factors That Influence Continuance Online ShoppingHamza Hadi ShaqmanNo ratings yet

- Chapter-VII ImplicationsDocument5 pagesChapter-VII ImplicationsSugan PragasamNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ijinfomgt 2020 102099Document12 pages10 1016@j Ijinfomgt 2020 102099Shidiq FadillahNo ratings yet

- Electronic Store Design and Consumer Choice An EmpDocument11 pagesElectronic Store Design and Consumer Choice An EmpDimitriNo ratings yet

- Consumer Intentions To Adopt Electronic Commerce - Incorporating Trust and Risk in The Technology Acceptance ModelDocument30 pagesConsumer Intentions To Adopt Electronic Commerce - Incorporating Trust and Risk in The Technology Acceptance ModelJefri ArdiansyahNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Students Perception of Online SDocument12 pagesFactors Affecting Students Perception of Online Sshivani bassiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 RRLSDocument4 pagesChapter 2 RRLSJanelle De TorresNo ratings yet

- Research Evaluation: Name of The ResearchDocument8 pagesResearch Evaluation: Name of The ResearchKim Yến VũNo ratings yet

- Key factors affecting online consumer purchase behaviorDocument14 pagesKey factors affecting online consumer purchase behaviorTrinh Ngô Thị HoàngNo ratings yet

- Research Take xxx2 AutosavedDocument27 pagesResearch Take xxx2 AutosavedMerr Fe PainaganNo ratings yet

- 514 VanishaDocument30 pages514 VanishaGopaul UshaNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Statisfaction and Loyalty Ini Online Shopping PDFDocument19 pagesFactors Influencing Statisfaction and Loyalty Ini Online Shopping PDFFelga YulandriNo ratings yet

- Customers Attitude Towards Online ShoppingDocument13 pagesCustomers Attitude Towards Online ShoppingHiraNo ratings yet

- Technology Concept Paper-FinalDocument9 pagesTechnology Concept Paper-Finaljovelyn rose dacilloNo ratings yet

- Perception About Shopping OnlineDocument14 pagesPerception About Shopping OnlineFarhana ZubirNo ratings yet

- Electronic Word-Of-Mouth: The Moderating Roles of Product Involvement and Brand ImageDocument19 pagesElectronic Word-Of-Mouth: The Moderating Roles of Product Involvement and Brand ImageSiti FatimahNo ratings yet

- 7b79 PDFDocument23 pages7b79 PDFFahad BataviaNo ratings yet

- E Commerce Supporting Mat With Cover Page v2Document9 pagesE Commerce Supporting Mat With Cover Page v2xyzhjklNo ratings yet

- Consumer Adoption F Internet ShoppingDocument11 pagesConsumer Adoption F Internet ShoppingnileshgokhaleNo ratings yet

- TRUSTING MOBILE PAYMENT: HOW THE TRUST-FACTOR FORMS THE MOBILE PAYMENT PROCESSFrom EverandTRUSTING MOBILE PAYMENT: HOW THE TRUST-FACTOR FORMS THE MOBILE PAYMENT PROCESSNo ratings yet

- Summary: Information Rules: Review and Analysis of Shapiro and Varian's BookFrom EverandSummary: Information Rules: Review and Analysis of Shapiro and Varian's BookRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Sweetie's Cookies Business PlanDocument32 pagesSweetie's Cookies Business PlanLiew202080% (41)

- TestDocument1 pageTestLiew2020No ratings yet

- SPSS Company Profile - Acquired by IBMDocument4 pagesSPSS Company Profile - Acquired by IBMThe Manual of Ideas100% (2)

- NECF 40days Fast and Pray Booklet 2019Document74 pagesNECF 40days Fast and Pray Booklet 2019Liew2020No ratings yet

- WP3 0-ErdDocument1 pageWP3 0-ErdLiew2020No ratings yet

- Outstanding Student LetterDocument3 pagesOutstanding Student LettersagarshiroleNo ratings yet

- The Five Love LanguagesDocument7 pagesThe Five Love LanguagesLiew2020100% (1)

- Basic Outline of A PaperDocument2 pagesBasic Outline of A PaperMichael MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Example Project CanvasDocument1 pageExample Project CanvasLiew2020No ratings yet

- ReferenceLetters PDFDocument14 pagesReferenceLetters PDFphoeberamosNo ratings yet

- Psychophysiology and The Five Love LanguagesDocument2 pagesPsychophysiology and The Five Love LanguagesLiew2020No ratings yet

- WP3 0-ErdDocument1 pageWP3 0-ErdLiew2020No ratings yet

- The Five Love LanguagesDocument7 pagesThe Five Love LanguagesLiew2020100% (1)

- Designing A Workflow-Based Scheduling Agent With Humans in The LoopDocument12 pagesDesigning A Workflow-Based Scheduling Agent With Humans in The LoopLiew2020No ratings yet

- The Future of ITDocument8 pagesThe Future of ITKira LiNo ratings yet

- 2013 PredictionsDocument15 pages2013 PredictionsLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- 19 Holiday in Year 2013Document1 page19 Holiday in Year 2013Liew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned Page PDFDocument1 pageScanned Page PDFLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Scanned PageDocument1 pageScanned PageLiew2020No ratings yet

- Deep Learning Based Eye Gaze Tracking For Automotive Applications An Auto-Keras ApproachDocument4 pagesDeep Learning Based Eye Gaze Tracking For Automotive Applications An Auto-Keras ApproachVibhor ChaubeyNo ratings yet

- tsb16 0008 PDFDocument1 pagetsb16 0008 PDFCandy QuailNo ratings yet

- WCM - March 2017-Final Version PDF - 4731677 - 01Document211 pagesWCM - March 2017-Final Version PDF - 4731677 - 01Antonio VargasNo ratings yet

- Rpo 1Document496 pagesRpo 1Sean PrescottNo ratings yet

- Audi A3 Quick Reference Guide: Adjusting Front SeatsDocument4 pagesAudi A3 Quick Reference Guide: Adjusting Front SeatsgordonjairoNo ratings yet

- SWOT AnalysisDocument6 pagesSWOT Analysishananshahid96No ratings yet

- OV2640DSDocument43 pagesOV2640DSLuis Alberto MNo ratings yet

- Siemens MS 42.0 Engine Control System GuideDocument56 pagesSiemens MS 42.0 Engine Control System GuideIbnu NugroNo ratings yet

- Digestive System Song by MR ParrDocument2 pagesDigestive System Song by MR ParrRanulfo MayolNo ratings yet

- Afrah Summer ProjectDocument11 pagesAfrah Summer Projectاشفاق احمدNo ratings yet

- Ohta, Honey Ren R. - Activity 7.2 (Reflection Agriculture and Religion)Document5 pagesOhta, Honey Ren R. - Activity 7.2 (Reflection Agriculture and Religion)honey ohtaNo ratings yet

- The Quantum Gravity LagrangianDocument3 pagesThe Quantum Gravity LagrangianNige Cook100% (2)

- VISCOSITY CLASSIFICATION GUIDE FOR INDUSTRIAL LUBRICANTSDocument8 pagesVISCOSITY CLASSIFICATION GUIDE FOR INDUSTRIAL LUBRICANTSFrancisco TipanNo ratings yet

- List of DEA SoftwareDocument12 pagesList of DEA SoftwareRohit MishraNo ratings yet

- CAM TOOL Solidworks PDFDocument6 pagesCAM TOOL Solidworks PDFHussein ZeinNo ratings yet

- Network Theory - BASICS - : By: Mr. Vinod SalunkheDocument17 pagesNetwork Theory - BASICS - : By: Mr. Vinod Salunkhevinod SALUNKHENo ratings yet

- BILL of Entry (O&A) PDFDocument3 pagesBILL of Entry (O&A) PDFHiJackNo ratings yet

- 7 React Redux React Router Es6 m7 SlidesDocument19 pages7 React Redux React Router Es6 m7 Slidesaishas11No ratings yet

- Speech TravellingDocument4 pagesSpeech Travellingshafidah ZainiNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Framework For Group Processing of Lyric Analysis Interventions in Music Therapy Mental Health PracticeDocument9 pagesConceptual Framework For Group Processing of Lyric Analysis Interventions in Music Therapy Mental Health Practiceantonella nastasiaNo ratings yet

- Case Acron PharmaDocument23 pagesCase Acron PharmanishanthNo ratings yet

- Lignan & NeolignanDocument12 pagesLignan & NeolignanUle UleNo ratings yet

- Surveying 2 Practical 3Document15 pagesSurveying 2 Practical 3Huzefa AliNo ratings yet

- Bonding in coordination compoundsDocument65 pagesBonding in coordination compoundsHitesh vadherNo ratings yet

- Funny Physics QuestionsDocument3 pagesFunny Physics Questionsnek tsilNo ratings yet

- EE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsDocument2 pagesEE114-1 Homework 2: Building Electrical SystemsGuiaSanchezNo ratings yet

- Ericsson 3G Chapter 5 (Service Integrity) - WCDMA RAN OptDocument61 pagesEricsson 3G Chapter 5 (Service Integrity) - WCDMA RAN OptMehmet Can KahramanNo ratings yet

- Rivalry and Central PlanningDocument109 pagesRivalry and Central PlanningElias GarciaNo ratings yet

- Citation GuideDocument21 pagesCitation Guideapi-229102420No ratings yet

- ROM Magazine V1i6Document64 pagesROM Magazine V1i6Mao AriasNo ratings yet