Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Search and Unemployment: Key Ideas in This Chapter

Uploaded by

ttongOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Search and Unemployment: Key Ideas in This Chapter

Uploaded by

ttongCopyright:

Available Formats

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 62 -

CHAPTER 6

Search and Unemployment

KEY IDEAS IN THIS CHAPTER

1. The model constructed in this chapter is intended to explain Statistics Canada labor

market data, and to organize our thinking about the role played by the labor market in

the macroeconomy.

2. Key labor market variables are the unemployment rate, the participation rate, and the

employment/population ratio.

3. In the Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides (DMP) labor search model, on the supply side

of the labor market, there are N consumers who choose between home production and

labor market search. On the demand side of the labor market, firms can either be idle

or can pay a cost to post vacancies. The number of searching would-be workers and

the number of searching firms determines the number of successful matches in the

labor market, through the matching function. Each successful match produces output.

4. For consumers, searching for work becomes more attractive the higher the market

wage, the higher is labor market tightness, and the higher is the unemployment

insurance benefit.

5. For firms, posting vacancies becomes more attractive the lower is the cost of posting

a vacancy, the lower is labor market tightness, the higher is productivity, and the

lower is the market wage.

6. In equilibrium, a higher unemployment insurance benefit increases the unemployment

rate, reduces labor market tightness, reduces the vacancy rate, and has an ambiguous

effect on the labor force.

7. In equilibrium, an increase in productivity increases labor market tightness, reduces

the unemployment rate, increases the vacancy rate, and increases the labor force.

8. In equilibrium, a decrease in matching efficiency reduces labor market tightness,

increases the unemployment rate, and may result in an increase or a decrease in the

vacancy rate. The labor force decreases.

9. A form of Keynesian analysis is introduced. In the DMP model, bargaining between a

matched firm and worker determines the wage, but bargaining strength can be

sticky of the result of social norms, which leads to Keynesian indeterminacy. It is

possible to have a bad Keynesian equilibrium where the wage and the unemployment

rate are inefficiently high.

Chapter 6: Search and Unemployment

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 63 -

NEW IN THE FOURTH EDITION

1. The entire chapter is new.

TEACHING GOALS

Including a version of the DMP model in an intermediate macroeconomics text is a

novelty. Students should not have difficulty understanding the model, but they may need

some additional help, as the approach is somewhat different than what we use in standard

competitive equilibrium models, for example in Chapter 5. However, it helps to think of

the labor market in terms of demand and supply sides. Then, it is possible to use what a

student knows from Chapter 5 to teach them about the DMP model. Workers and firms

care about the wage in the same way they do in a competitive model, but now the market

clears in a different way. Workers care not only about the wage, but the employment

insurance benefit (because their job search may be unsuccessful) and labor market

tightness (which determines the chances of finding a job). Would-be employers care

about labor market tightness and the cost of posting a vacancy, as well as the market

wage. The matching function, which determines the number of successful matches as a

function of matching efficiency and the numbers of firms and consumers searching, is an

important concept. In this case, appeal to what students know about the production

function, as the matching function has the same properties. Then, one can appeal by

analogy to production so that the student understands how the matching process takes

place.

It is important first to understand the labor market data. The DMP model is very nice, as

the variables in the model match up almost exactly with the labor market data as

measured. The unemployed are those who chose to search but were unsuccessful, the

labor force is the number of people who actively searched and found a job (employed)

plus the number who actively searched and were unsuccessful (the unemployed), etc.

The experiments in the model increase in the employment insurance benefit, increase in

productivity, decrease in matching efficiency are all useful in understanding recent

economic events and less-recent ones. A problem in Canada is that Statistics Canada does

not collect vacancy data, so sometimes it might be useful to bring in U.S. data. The

Beveridge curve correlation is particularly helpful.

The Keynesian DMP Model comes from ideas in work by Roger Farmer. This is a nice

way to understand Keynesian ideas (for starters). With bargaining indeterminacy the

wage could be stuck at too high a level, with an unemployment rate that is too high. We

dont deal with Keynesian economic policies in this chapter, leaving that for later

chapters.

Instructors Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 64 -

CLASSROOM DISCUSSION TOPICS

It should not be hard to get students talking about unemployment. Most of them should

know someone who has been unemployed, or they have read about unemployment as it

relates to the recent recession. However, students may not understand how

unemployment is actually defined, or how economists think about it. An important

feature of the DMP model is that there will be unemployment under any circumstances,

and students should understand that we cannot make unemployment go away, nor should

we want it to.

It will be helpful if students understand why a search-model approach is necessary to

understanding unemployment. Get them thinking about what an unemployed person is

actually doing, and what is motivating them. Unemployment is an economically

measurable activity, and we want to take a scientific approach to thinking about it.

Also, get the students to think about what motivates firms to search for workers to fill job

openings. Why is searching for workers costly? What difficulties does a firm face in

hiring workers? How does matching between firms and workers take place? Why is the

market for labor similar to, and different from, the market for a good or service?

Students should be encouraged to think about government intervention and how it matters

for labor market behavior. What will employment insurance do? How can the

government speed up or slow down the matching process in the labor market?

OUTLINE

1. The Behaviour of the Unemployment Rate, the Participation Rate, and the

Employment/Population Ratio in Canada

a) Unemployment Rate, participation rate, and employment/population ratio: data.

b) Key determinants of the unemployment rate: aggregate economic activity,

demographics, government intervention, mismatch

2. The Diamond-Mortensen-Pissarides Model of Search and Unemployment

a) Consumers

b) Firms

c) Matching

d) Optimization by Consumers

e) Optimization by Firms

f) Equilibrium

g) An increase in the unemployment insurance benefit

h) An increase in productivity

i) A decrease in matching efficiency

j) The Beveridge curve

k) A Keynesian DMP model

Chapter 6: Search and Unemployment

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 65 -

TEXTBOOK QUESTION SOLUTIONS

Problems

1. More labour-saving devices has the effect of reducing the payoff to working at home

for all consumers, which reduces v(Q) for each value of Q. As a result, the curve in

panel (a) of Figure 6.1 shifts up. In equilibrium, Q increases, but j remains

unchanged. The unemployment rate and the vacancy rate are unaffected, but the labor

force Q increases. Since j = A/Q, therefore the number of firms A increases.

Aggregate output Y = Qem(1,j), so Y increases, as Q has risen and j is unchanged.

Labour saving devices makes searching for work more attractive relative to working

at home for consumers. With more consumers in the market, labour market tightness

tends to go down, which attracts more firms into the labour market. Ultimately, the

number of active firms increases proportionally to the number of consumers searching

for work, and there is no change in labour market tightness in equilibrium. Output

goes up because there are more successful matches in the labour market.

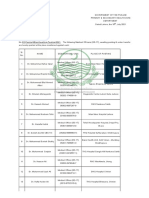

Figure 6.1

Instructors Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 66 -

2. (i) With a subsidy s to hiring a worker, for a successful match, the surplus of the firm

is z+s-w, the surplus of the worker is w-b, total surplus is z+s-b, and the wage

(from Nash bargaining) is w=a(z+s)+(1-a)b. Then, on the supply side of the

labour market, the equation determining the curve in panel (a) of Figure 6.2 is

given by

v(Q)=b+em(1,j)a(z+s-b),

and on the demand side of the market, the equation determining j is

(k/((1-a)(z+s-b)))=em((1/j),1)

Then, in Figure 6.2, comparing the equilibrium when s=0 to one with s>0, the

subsidy acts to increase labour market tightness, j, and to increase the labour force, Q.

The subsidy acts to induce more firms to enter the labor market to search for workers,

which makes j=(A/Q) higher. This in turn acts to make search more attractive for

workers, as it is now easier to find a job. As well, the subsidy increases the wage,

which further increases the incentive to search for work. The unemployment rate is 1-

em(1,j), which falls when j increases, so the subsidy reduces the unemployment rate.

(ii) If the government pays would-be workers to stay out of the labour market, this

has no effect on the demand side (firms' behavior). However, the supply side of

the labour market is now characterized by the equation

q+v(Q)=b+em(1,j)a(z+s-b),

Therefore, when q>0, this shifts the curve in the upper panel of Figure 6.2 to the

right. There is no effect on labour market tightness, j, and therefore no effect on the

unemployment rate. However, Q falls. Since j does not change, this implies that A

falls as well, since j=(A/Q). Therefore, this policy has the effect not only of reducing

the number of would-be workers looking for work, but it reduces the number of firms

searching for workers. The policy has an unintended side effect and has no effect on

the unemployment rate.

Chapter 6: Search and Unemployment

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 67 -

Figure 6.2

3. The lower recruiting cost, k, affects only the demand side of the labour market. In

Figure 6.3, labour market tightness increases from j to j , and the labor force

increases from Q to Q . The unemployment rate is 1-em(1,j), which decreases

because of the increase in j, and the vacancy rate is 1-em((1/j),1), which increases.

Since j=(A/Q), and since Q and j increase, A also increases. Aggregate output is

Qem(1,j)z, which increases, as Q and j both increase. Thus, the lower cost of

recruiting induces more firms to enter the labor market, which increases labour

market tightness, inducing more workers to enter the labour market to search for

work, as the chances are now better of finding a job.

Instructors Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 68 -

Figure 6.3

4. For this question, re-define labor market tightness as j = (A+G)/Q. Then, the diagram

we work with looks identical to Figure 6.10 in Chapter 6, and Q and j are determined

as in Figure 6.10. Note in particular that G is irrelevant for determining Q and j, so

government activity is irrelevant for the size of the labor force and labor market

tightness. Further, government activity will not matter for the unemployment rate, the

vacancy rate, or aggregate output. However, since j and Q do not change when G

changes, A+G = jQ does not change either. But then an increase in G must reduce A

by the same amount. Therefore, government activity simply reduces the number of

private firms by an equal amount, and there is otherwise no effect on economic

activity. The key to this result is that the government was assumed to be no better or

worse at producing output than private sector firms. Therefore, the scale of

government activity could not matter for aggregate variables.

5. In the Keynesian DMP model, the wage w is indeterminate and, given w, equations

(6.6) and (6.8) solve for Q and j, i.e.

Chapter 6: Search and Unemployment

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 69 -

v(Q)=b+em(1,j)w, (1)

and

(k/(z-w))=em((1/j),1) (2)

Suppose that w is too high in equilibrium, which implies that Q and j are too low

relative to what is socially efficient. If the government were to subsidize successful

matches by paying s to a firm when a match occurs, then equation (2) becomes

(k/(z-w+s))=em((1/j),1), (3)

since the firm's surplus from a match (the firm's profit) is now z-w+s. In Figure 6.4,

this has the effect of increasing j and Q. As long as the government makes s

sufficiently large, it can correct the social inefficiency. The subsidy makes it more

attractive for firms to enter the labour market to search for workers, which in turn

attracts more would-be workers into the labour market as it is now easier to get a job.

The labor force increases, the unemployment rate decreases, the vacancy rate

increases, and GDP increases. In Keynesian models, there always exists some price

distortion - goods and/or labor are mispriced - and this type of inefficiency can be

corrected just as we would correct a standard type of inefficiency such as an

externality. Typically, we can correct a negative externality with a Pigouvian tax -

e.g. a tax on gasoline, as burning gas causes pollution. A positive externality can be

corrected with a subsidy. If the government were to subsidize a firm for posting a

vacancy, then equation (2) becomes

((k-s)/(z-w))=em((1/j),1), (4)

as now the vacancy-posting cost is k-s. Qualitatively, this has the same effects as in

Figure 6.4, so in that sense it does not matter if the subsidy is aimed at reducing

recruiting costs or subsidizing successful matches. In fact, it literally makes no

difference to the government which way the subsidy is implemented. Suppose that the

government wants to achieve a particular value for labor market tightness, j*, through

a subsidy. If government subsidizes successful matches with a subsidy s , then

equation (3) gives

k=(z-w+s )em(1/(j ),1), (5)

and if the government subsidizes recruiting with a subsidy s , then equation (4)

gives

k-s =(z-w)em(1/(j ),1). (6)

Then, subtract equation (6) from equation (5) to get

s =s em(1/(j ),1) (7)

Instructors Manual for Macroeconomics, Fourth Canadian Edition

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 70 -

But in equation (7), the left-hand side is the cost of the subsidy program per active

firm, in the first case, and the right-hand side is the cost of the subsidy program per

active firm in the second case. Since j=j for both programs and Q is the same for

both programs, therefore A=j Q is the same for both programs, i.e. the number of

active firms is the same for each program. Therefore, to get the same effect (a given j)

each subsidy program has exactly the same cost for the government, so they are

identical.

6. If all social welfare programs simultaneously become more generous, suppose that we

represent this as a payment p to each person not in the labor force, and an increase by

p in the employment insurance benefit. Then, the equation that summarizes behavior

on the supply side of the labour market becomes

v(Q) + p = b + p + em(1,j)a(z-b-p),

or, simplifying,

v(Q) = b + em(1,j)a(z-b-p).

As well, the equation summarizing demand-side behaviour in the labour market can be

written as

em(1/j,1) = k/(1-a)(z-b-p)

Therefore, in Figure 6.4, labour market tightness falls from j

1

to j

2

, and the labour

force falls from Q

1

to Q

2

. As a result, the unemployment rate increases and the

vacancy rate decreases. The number of firms is A=jQ, so A decreases. As well, output

is Y=zQem(1,j), so output falls as well. Consumers are affected by two social

programs one which pays a benefit to people not in the labour force, and one that

pays an employment insurance benefit to the unemployed. Since the consumer

receives the employment insurance benefit only in the event that search for work is

unsuccessful, the increase in generosity of all social programs will on net discourage

consumers from searching for work. Further, more generous social programs reduces

the total surplus from a successful match, and this discourages firms from posting

vacancies. On net, labour market tightness goes down, the labour force contracts, and

aggregate output decreases, with the unemployment rate increasing and the vacancy

rate decreasing.

Chapter 6: Search and Unemployment

Copyright 2013 Pearson Canada Inc.

- 71 -

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- SSNDocument1,377 pagesSSNBrymo Suarez100% (9)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- 0403 Glossary of Life Insurance TermsDocument6 pages0403 Glossary of Life Insurance TermsttongNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- UFO Midwest Magazine April2011Document16 pagesUFO Midwest Magazine April2011Jimi HughesNo ratings yet

- SMChap 018Document32 pagesSMChap 018testbank100% (8)

- Case Study, g6Document62 pagesCase Study, g6julie pearl peliyoNo ratings yet

- American Woodworker No 171 April-May 2014Document76 pagesAmerican Woodworker No 171 April-May 2014Darius White75% (4)

- Project On International BusinessDocument18 pagesProject On International BusinessAmrita Bharaj100% (1)

- Amex Case StudyDocument12 pagesAmex Case StudyNitesh JainNo ratings yet

- Sydenham To Bankstown Preferred Infrastructure Report OverviewDocument54 pagesSydenham To Bankstown Preferred Infrastructure Report OverviewttongNo ratings yet

- Deloitte Uk Life Insurance FuturesDocument8 pagesDeloitte Uk Life Insurance FuturesttongNo ratings yet

- Project Overview Sydney Metro Western Sydney Airport September 2020Document48 pagesProject Overview Sydney Metro Western Sydney Airport September 2020ttongNo ratings yet

- Guide LGBITQIA V8 DigitalDocument76 pagesGuide LGBITQIA V8 DigitalttongNo ratings yet

- How Crediting Rates and Investment Returns WorkDocument2 pagesHow Crediting Rates and Investment Returns WorkttongNo ratings yet

- Pre and Post Merger P-E RatiosDocument5 pagesPre and Post Merger P-E RatiosPeter OnyangoNo ratings yet

- A2 Reserve Bank of Australia - Monetary Policy Changes A2 Reserve Bank of Australia - Monetary Policy ChangesDocument5 pagesA2 Reserve Bank of Australia - Monetary Policy Changes A2 Reserve Bank of Australia - Monetary Policy ChangesttongNo ratings yet

- Rates 3Document171 pagesRates 3ttongNo ratings yet

- UAM Chapter 1: 1.2 What Is An Actuary?Document3 pagesUAM Chapter 1: 1.2 What Is An Actuary?ttongNo ratings yet

- Question 2Document4 pagesQuestion 2ttongNo ratings yet

- Pre and Post Merger P-E RatiosDocument4 pagesPre and Post Merger P-E RatiosttongNo ratings yet

- Rates 1Document445 pagesRates 1ttongNo ratings yet

- TestbankDocument12 pagesTestbankttongNo ratings yet

- E 01 BhistDocument4 pagesE 01 BhistttongNo ratings yet

- Star ESG: Real-World Economic Scenario GenerationDocument8 pagesStar ESG: Real-World Economic Scenario GenerationttongNo ratings yet

- 103 PPT BekkerDocument40 pages103 PPT BekkerttongNo ratings yet

- ACTL3003 Assignment Part A and BDocument2 pagesACTL3003 Assignment Part A and BttongNo ratings yet

- Herfindahl IndexDocument5 pagesHerfindahl IndexttongNo ratings yet

- MakeDocument2 pagesMakettongNo ratings yet

- Assessment Centres 20121Document7 pagesAssessment Centres 20121zaidi10No ratings yet

- The Affinity Process: Getting People To Like You or Approve of YouDocument10 pagesThe Affinity Process: Getting People To Like You or Approve of YouttongNo ratings yet

- Example Behavioral QuestionsDocument1 pageExample Behavioral QuestionsttongNo ratings yet

- Concentration RatioDocument4 pagesConcentration RatiottongNo ratings yet

- Herfindahl IndexDocument5 pagesHerfindahl IndexttongNo ratings yet

- Liverpool Youth Council Application Form: Personal DetailsDocument2 pagesLiverpool Youth Council Application Form: Personal DetailsttongNo ratings yet

- Matching Theory (Economics)Document3 pagesMatching Theory (Economics)ttongNo ratings yet

- 7389706Document23 pages7389706drbunheadNo ratings yet

- Google BookmarksDocument1 pageGoogle BookmarksttongNo ratings yet

- Excel Bill of Materials Bom TemplateDocument8 pagesExcel Bill of Materials Bom TemplateRavi ChhawdiNo ratings yet

- 2113T Feasibility Study TempateDocument27 pages2113T Feasibility Study TempateRA MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Sales Account Manager (Building Construction Segment) - Hilti UAEDocument2 pagesSales Account Manager (Building Construction Segment) - Hilti UAESomar KarimNo ratings yet

- Value Chain AnalysisDocument4 pagesValue Chain AnalysisnidamahNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: Business Studies Class XI Anmol Ratna TuladharDocument39 pagesChapter One: Business Studies Class XI Anmol Ratna TuladharAahana AahanaNo ratings yet

- AIIMS Mental Health Nursing Exam ReviewDocument28 pagesAIIMS Mental Health Nursing Exam ReviewImraan KhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Nor-man KusainNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE 5 PERFORMANCE TASKs 1-4 4th QuarterDocument3 pagesSCIENCE 5 PERFORMANCE TASKs 1-4 4th QuarterBALETE100% (1)

- Strategy GlossaryDocument15 pagesStrategy GlossaryMahmoud SaeedNo ratings yet

- DJDocument907 pagesDJDeepak BhawsarNo ratings yet

- Export - Import Cycle - PPSXDocument15 pagesExport - Import Cycle - PPSXMohammed IkramaliNo ratings yet

- Costos estándar clase viernesDocument9 pagesCostos estándar clase viernesSergio Yamil Cuevas CruzNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 12 Climate ChangeDocument5 pagesLesson Plan 12 Climate ChangeRey Bello MalicayNo ratings yet

- Insert BondingDocument14 pagesInsert BondingHelpful HandNo ratings yet

- Government of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentDocument3 pagesGovernment of The Punjab Primary & Secondary Healthcare DepartmentYasir GhafoorNo ratings yet

- SRC400C Rough-Terrain Crane 40 Ton Lifting CapacityDocument1 pageSRC400C Rough-Terrain Crane 40 Ton Lifting CapacityStephen LowNo ratings yet

- Amo Plan 2014Document4 pagesAmo Plan 2014kaps2385No ratings yet

- Case 1 1 Starbucks Going Global FastDocument2 pagesCase 1 1 Starbucks Going Global FastBoycie TarcaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledMOHD JEFRI BIN TAJARINo ratings yet

- Differentiation: Vehicle Network SolutionsDocument1 pageDifferentiation: Vehicle Network SolutionsДрагиша Небитни ТрифуновићNo ratings yet

- Activity2 Mba 302Document2 pagesActivity2 Mba 302Juan PasyalanNo ratings yet

- Culinary Nutrition BasicsDocument28 pagesCulinary Nutrition BasicsLIDYANo ratings yet

- KS4 Higher Book 1 ContentsDocument2 pagesKS4 Higher Book 1 ContentsSonam KhuranaNo ratings yet